Abstract

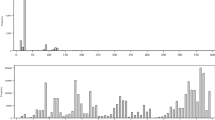

Research consistently demonstrates that differences between the policy preferences of high- and low-income individuals are surprisingly small, at least at the aggregate level. We depart from this work by considering the size of income-based differences in opinion within political parties. To do so, we use responses to 144 policy-specific questions in the 2010–2020 Cooperative Election Study (CES). Our effort demonstrates that differences in opinion among the rich and poor tend to be larger within the parties than in the overall population. Interestingly, these gaps are largest among Democrats. We find that these larger gaps persist even after accounting for the party’s racial and ethnic diversity. Furthermore, among Democrats, class-based gaps in opinion are larger than the gaps we observe among other potential intraparty cleavages, such as age, gender, and religiosity. Our results suggest important implications for the growing literature on representational inequality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, because of these high correlations, Gilens (2015) focuses much of his empirical analysis on the subset of policies for which there is at least 10-percentage-point gap between the preferences of the top and bottom income deciles or the top and middle deciles.

The scope of the Maks-Solomon and Rigby analysis is more modest than our analyses here. Their conclusions are based on survey data of 11 economic issues and 7 social issues.

Likewise, the top decile in 2020 includes all 1,431 respondents with incomes above $150,000, plus a sample of 2,129 of the 3,560 respondents with incomes between $120,000 and $149,999. On average, each decile includes 6,067 people.

Of the four partisan subgroups we analyze, high-income Democrats most frequently take the position consistent with their partisanship, doing so 77% of the time. By comparison, rich Republicans hold ideologically consistent views 64% of the time, low-income Democrats do 65% of the time, and low-income Republicans 56% of the time. In Online Appendix F we present data on consistency.

Alternatively, we could simply identify all issues for which rich and poor opinion lies on opposite sides of the 50% threshold (ignoring the size of the opinion gap). The problem with doing so is that an issue supported by 51% of the rich, but only 49% of the poor would be counted as a disagreement. We, however, are reluctant to imbue this small difference in opinion with much meaning.

We also consider the expectation, from Gelman et al. (2008), that partisan divides in part stem from Democrats living in richer states. In Online Appendix D, we show that opinion gaps look similar for partisans living in the 25 states with the highest median household income and those with the lowest. The opinion gap for Republicans in the richest states is 0.115, compared to 0.106 in poor states; for both rich-state and poor-state Democrats, it is 0.144.

Our main measure of opinion gaps above are equivalent to using the coefficient from a linear regression of opinion on high-income without any controls; our approach in this section closely mirrors that analysis.

These differences are statistically significant. In Online Appendix C, we plot these estimates with 95% confidence intervals produced by bootstrapping.

References

Abramowitz, A. I., & Saunders, K. L. (2005). Why can’t we all just get along? The reality of a polarized America. The Forum, 3(2), Article 1.

Achen, C. H., & Bartels, L. M. (2016). Democracy for realists: Why elections do not produce responsive government. Princeton University Press.

Bafumi, J., & Shapiro, R. Y. (2009). A new Partisan voter. Journal of Politics, 71(1), 1–24.

Bartels, L. M. (2008). Unequal democracy: The political economy of the new gilded age. Princeton University Press.

Branham, J. A., Soroka, S. N., & Wlezien, C. (2017). When do the rich win? Political Science Quarterly, 132(1), 43–62.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American Voter. University of Chicago Press.

Enns, P. K. (2015). Relative policy support and coincidental representation. Perspectives on Politics, 13(4), 1053–1064.

Enns, P. K., & Wlezien, C. (2011). Group opinion and the study of representation. In K. Peter (Ed.), Who gets represented? (pp. 1–26). Russell Sage.

Erikson, R. S., & Tedin, K. L. (2019). American public opinion: Its origins, context, and impact. Routledge.

Fiorina, M. P. (2017). Unstable majorities: Polarization, party sorting and political stalemate. Hoover Institution Press.

Fiorina, M. P., & Abrams, S. J. (2008). Political polarization in the American public. Annual Review of Political Science, 11, 563–588.

Galvin, D. J. (2010). Presidential Party Building: Dwight D. Eisenhower to George W. Bush. Princeton University Press.

Gelman, A., Park, D., Shor, B., & Cortina, J. (2008). Red state, blue state, rich state, poor state: Why Americans vote the way they do. Princeton University Press.

Gilens, M. (2012). Affluence and influence: Economic inequality and political power in America. Princeton University Press.

Gilens, M., & Page, B. (2014). Testing theories of American politics: Elites, interest groups, and average citizens. Perspectives on Politics, 12, 564–581.

Green, D., Palmquist, B., & Schickler, E. (2002). Partisan Hearts & Minds: Political Parties and the Social Identities of Voters. Yale University Press.

Grossman, M., & Hopkins, D. A. (2016). Asymmetic politics: Ideological republicans and group interest democrats. Oxford University Press.

Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(3), 405–31.

Iyengar, S., & Westwood, S. J. (2015). Fear and loathing across party lines: New evidence on group polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 690–707.

Kastellec, J. P., Lax, J. R., Malecki, M., & Phillips, J. H. (2015). Polarizing the electoral connection: Partisan representation in supreme court confirmation politics. The Journal of Politics, 77(3), 787–804.

Krimmel, K., Lax, J. R., & Phillips, J. H. (2016). Gay rights in Congress: Public opinion and (mis)representation. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80(4), 888–913.

Lax, J. R., Phillips, J. H., & Zelizer, A. (2019). The party or the purse? Unequal representation in the US senate. American Political Science Review, 113(4), 917–940.

Levendusky, M. (2009). The Partisan sort: How liberals became democrats and conservatives became republicans. University of Chicago Press.

Maks-Solomon, C., & Rigby, E. (2019). Are democrats the party of the poor? Partisanship, class, and representation in the U.S. senate. Political Research Quarterly, 73(4), 848–65.

Mason, L. (2015). I disrespectfully agree’: The differential effects of partisan sorting on social and issue polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(1), 128–145.

Mayer, W. G. (1996). The divided democrats: Ideological unity, party reform, and presidential elections. Westview Press.

McCarty, N. (2019). Polarization: What everyone needs to know. Oxford University Press.

Meltzer, A. H., & Richard, S. F. (1981). A rational theory of the size of government. Journal of Political Economy, 89(5), 914–927.

Rigby, E., & Wright, G. C. (2013). Political parties and representation of the poor in the American states. American Journal of Political Science, 57(3), 552–65.

Rosenfeld, S. (2018). The polarizers: Postwar architects of our Partisan era. University of Chicago Press.

Soroka, S. N., & Wlezien, C. (2008). On the limits to inequality in representation. PS: Political Science and Politics, 41(2), 319–327.

Stonecash, J. (2000). Class and party in American politics. Westview Press.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to our colleagues Robert Shaprio and Max Goplerud for their feedback and advice. We acknowledge computing resources from Columbia University’s Shared Research Computing Facility project (supported by NIH Research Facility Improvement Grant 1G20RR030893-01 and New York State Empire State Development, Division of Science Technology and Innovation Contract C090171).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical Approval

This is an observational study using publicly available survey data and is not covered by human subject review.

Replication Data

Replication files are available on the Political Behavior Dataverse: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/3KNHWH.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Auslen, M., Phillips, J.H. Divided by Income? Policy Preferences of the Rich and Poor Within the Democratic and Republican Parties. Polit Behav (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-024-09927-9

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-024-09927-9