Abstract

We consider how frames highlighting religious values shape opinion among individuals who may experience social identity conflict. White evangelical Republicans have ardently supported Donald Trump’s restrictionist stances towards refugees, yet those partisan policy stances exist in tension with evangelical Christian values emphasizing care for vulnerable strangers. Our pre-registered national experiment tests whether a religious message can move white self-identified evangelical Republicans’ opinions relating to refugees. The pro-refugee Christian values message increases favorable attitudes on some, but not all, measures. The effect is comparatively stronger among those who are more committed to their evangelical identity; unexpectedly, those who identify as strong Republicans are not more resistant to the message. These results demonstrate that moral reframing, which is known to shape attitudes in other domains, can affect self-identified evangelical Republicans’ attitudes on refugees, potentially shifting the national discussion of refugees in the U.S. The finding is all the more significant given highly partisan debates over refugees during the Trump presidency, which may have made partisans’ opinions especially rigid at the time of our experiment. Our results also speak to the relevance of identity strength in conditioning the impact of religious values frames.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Few groups have been as supportive of Donald Trump and the Republican Party as white evangelicals. Various studies demonstrate the depth, breadth, and persistence of this group’s support of Trump and his issue positions (e.g., Jones et al., 2018; Margolis, 2020; Whitehead et al., 2018). Evangelical and Republican identities often reinforce each other, as when evangelical leaders cite religious values in support of positions Republicans typically hold (e.g., opposition to abortion, support for religious freedom, conservative views on LGBTQ + issues). However, at times evangelical and Republican identities are in conflict.

The tension between partisan and religious identities for evangelical Republicans was especially clear in the context of refugee politics during the Trump presidency. The Republican Party’s restrictionist stance on refugees was strong, clear, and visible. One of its most salient manifestations involved President Trump’s policies and rhetoric aimed at the massive Syrian refugee diaspora. During his 2016 presidential campaign, while civil war flared in Muslim-majority Syria, Trump called for “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States” (Taylor, 2015) and referred to Syrian refugees as “definitely, in many cases, ISIS-aligned…the great Trojan Horse” (Blake, 2016). Once in office, Trump signed an executive order that restricted travel and refugee admissions, indefinitely barred Syrian refugees, and decreased the annual national refugee resettlement limit from 85,000 in 2016 to 15,000 in 2021.Footnote 1

In direct contrast, many (though not all) evangelical leaders and organizations (e.g., The National Association of Evangelicals and the Southern Baptist Convention) articulated religiously-grounded calls for increased openness to refugees (Newman, 2018). For example, in 2017, over 500 evangelical leaders from all 50 states signed an open letter, published in the Washington Post, that “call[ed] on President Trump and Vice President Pence to support refugees” (Miller, 2017). Such calls are often explicitly Christian, drawing from the words of Jesus. Despite these messages, white evangelicals overwhelmingly side with Trump and the Republican Party: e.g., opposition to resettling Syrian refugees has been higher among this group than any other religious group in the U.S. (Hartig, 2018; Jones et al., 2018; Newman, 2018).

How rigid are these stances? We examine whether explicitly religious messaging can move self-identified white evangelical Republicans toward greater openness to refugees and away from the restrictionist partisan position. The specific instance of self-identified evangelical Republicans and refugee politics is important because it connects to broad theoretical questions about conflicting social identities and the potential power of counter-partisan moral messages.Footnote 2 In the current political context, people’s social identities (e.g., their partisan, ideological, religious, racial/ethnic, gender identities) often reinforce each other, strengthening the power of partisan identities (Mason, 2018; Mason & Wronski, 2018). In instances of potential social identity conflict, at least during the Trump era, partisanship dominates ideological, gender, and religious identities (e.g., Barber & Pope, 2019; Cassese, 2020; Margolis, 2020). Yet, research on moral framing suggests that certain messages – those framed around a group’s core values – might be effective in moving opinion away from partisan stances (e.g., DeMora et al., 2021; Feinberg & Willer, 2013, 2015). We apply that intuition to opinion about refugees to generate new insights into the relevance of religious values frames, a specific type of moral values frame, for partisan stances.

We make three contributions. First, we extend the moral framing literature by applying it to refugee politics. Previous studies have found moral frames emphasizing values like patriotism, purity, and egalitarianism can shift policy opinions away from partisan positions in a small number of highly contentious domains like same-sex marriage (Feinberg & Willer, 2015) and the environment (Feinberg & Willer, 2013; Wolsko et al., 2016). If moral framing can move evangelical Republicans away from partisan positions on hot button issues that divide the parties, these frames may ease partisan polarization. Moreover, given the partisan division on refugee politics (e.g., Hartig, 2018; Newman, 2018), even small changes among self-identified evangelical Republicans could shift the national debate. Second, we examine the power of counter-partisan moral framing during the highly-polarized Trump era in an issue domain where partisan positions are clear and forcefully articulated. Earlier studies found framing effects on immigration attitudes in less polarized periods (e.g., Margolis, 2018a), but refugee politics during the Trump presidency were so polarized that frames may no longer move attitudes (Skinner, 2022; but see Collingwood et al., 2018). Third, we explore the moderating effects of source cues and the strength of people’s partisan and religious identities on moral framing. According to Feinberg and Willer (2019, 5), “potential moderating factors that either strengthen or weaken the effects [of moral frames] remain largely unexplored.” We show that some evangelical Republicans are more open to framing effects on this issue than others.

We report on a pre-registered survey experiment administered to a self-identified white evangelical Republican sample (replication data for this research can be found in the Harvard dataverse). Our results show both the power and limits of partisan and religious forces in shaping public opinion. A religious message can push self-identified evangelical Republicans’ views away from the Republican position, increasing support for more resettlement of refugees in the U.S. and boosting feelings of warmth toward refugees. However, the message does not raise support for providing government benefits to refugees already in the country. The message was especially powerful for those who more strongly identify as evangelical. Surprisingly, self-identified evangelical Republicans who strongly identify with the party are not more resistant to the pro-refugee message. In fact, we find some evidence of willingness among even the most strongly Republican evangelicals to shift opinion in favor of refugees. This finding was unexpected and important: it underscores the complexity of opinion among self-identified white evangelical Republicans – while this subgroup may be among the most ardent supporters of the party’s current de facto head (Trump), many did not reject a message running counter to his position when that message highlighted their religious values.

Existing Work on Public Opinion Toward Refugees

A great deal of scholarship seeks to understand forces that shape public opinion toward immigrants and refugees (for a review, see Hainmueller & Hopkins, 2014), including the role of elite frames (Druckman et al., 2013; Haynes et al., 2016). In the interest of space, we focus our discussion on work that has considered Americans’ attitudes toward Syrian refugees – the focus of much recent scholarship and a salient group of refugees at the time we fielded our study. Studies of immigration and refugee attitudes often focus on the extent to which opinions are driven by realistic threats like economic or security concerns compared to cultural threats like racial prejudice. In the case of refugees, scholarship suggests that cultural threats are more relevant to attitudes, although realistic threats also play a role. For example, Nassar (2020a) finds that, for whites, negative feelings toward Muslims and Middle Eastern immigrants are more strongly associated with lower support for Syrian refugee resettlement than are concerns about terrorism. Along similar lines, experimental work has found support is significantly lower when refugees are depicted as Muslim compared to Christian (Adida et al., 2019; Filindra et al., 2022; Nassar, 2020b), while Muslim stereotypes may be at the heart of evangelicals’ opposition to resettling Syrian refugees (Roy, 2023). Using a conjoint design, Adida et al. (2019) also find that individuals are more supportive of refugees who are women, high-skilled, and fluent in English, though these effects are smaller than the negative effects found for Muslim refugees. Filindra et al. (2022) further find that support for Syrian refugees is shaped by economic considerations.

Bias against Syrian refugees (especially those who are Muslim) is particularly pronounced among Republicans (Adida et al., 2019; Nassar, 2020b), Christians (Adida et al., 2019; Roy, 2023; but see Skinner, 2022), and those who regularly watch Fox News (Nassar, 2020b; Newman, 2018). In the context of the Syrian refugee crisis, Fox News had three times as many mentions of Syrian refugees being Muslim compared to CNN or MSNBC, and more extensive coverage of refugees as security threats (Nassar, 2020b). This may in part explain why white evangelicals, who regularly watch Fox News, are so highly opposed to admitting Syrian refugees into the U.S. (Newman, 2018).

If attitudes are so negative toward refugees, especially under the specter of the Syrian refugee crisis and especially among white evangelical Republicans, are there any interventions that might lead to less restrictive attitudes? Some scholarship shows that encouraging individuals to take the perspectives of refugees can lead to greater inclusivity (Adida et al., 2018), including among Republicans. However, other work has found null effects of a sympathy frame on white Christians (Skinner, 2022). As another intervention, Collingwood et al. (2018) demonstrate how media coverage of protests around Trump’s Muslim ban increased opposition to the ban by painting the policy as counter to American values; this obtained not only among Democrats, but Republicans as well. Furthermore, these effects persisted a year later (Oskooii et al., 2021). As we detail more in the next section, some additional work has also considered how religious messages can lead to more pro-immigrant attitudes (Margolis, 2018a; Nteta & Wallsten, 2012), though that work has not explicitly considered refugees. In the next section, we develop our theoretical expectations for how individuals might navigate religious values messages that conflict with their other identities.

When Dual Partisanship and Social Forces Duel

Social and partisan identities play a profound role in shaping public opinion and voting behavior (e.g., Green et al., 2002; Huddy et al., 2015; Mason 2018; Mason et al., 2021). In recent decades in the U.S., various social groups have sorted themselves increasingly into distinct political party groups, which for many individuals has meant a closer alignment between their partisan and other social identities (e.g., Mason, 2018). During this time, more whites, evangelical Protestants, and ideological conservatives have identified with the Republican Party (e.g., Layman, 2001; Levendusky, 2009). When social identities overlap with party identification, party identification tends to strengthen, especially when individuals consciously perceive that their religious or ethnic group is closely linked to a party (Mason & Wronski, 2018). But, what happens when dual social and partisan forces are made to duel? We theorize over this question to derive a set of hypotheses that recognize the predominant role of partisanship in public opinion, while acknowledging the potential of moral frames to nudge some individuals away from party positions.

We focus on self-identified white evangelical Protestants because their connection to the Republican Party is strong, and some Republican and evangelical elites offer conflicting messages on refugee politics – a necessary dynamic for our study. White evangelicals have supported Republican candidates at high levels for several election cycles (e.g., Layman, 2001), including the 2016 and 2020 elections with Trump on the ticket (Margolis, 2020; Burge, 2021). Consequently, white evangelicals may be especially likely to adopt, maintain, and defend policies that Trump and other Republicans espouse. In fact, this has been the case for attitudes on immigration and refugee policy (Newman, 2018; Melkonian-Hoover & Kellstedt, 2019; Wong, 2018).

In the current political context and in the specific realm of refugee politics, when white evangelical Republicans’ religious and partisan identities conflict, four related factors suggest that pro-refugee religious values frames in conflict with Trump’s positions will exert no effect. First, while scholars have assumed for decades that religious identities affect political views, recent scholarship demonstrates the reverse as well: partisanship shapes religious identities, behaviors, and beliefs (Campbell et al., 2018; Margolis, 2018b; Miles, 2019). Second, when new issues arise, partisans often adopt the positions party elites articulate (Lenz, 2013). As the Syrian refugee crisis captured the world’s attention in 2015, Democrats and Republicans staked out opposing positions. President Barack Obama committed to allowing additional Syrian refugees to resettle in the U.S. Then-presidential candidate Donald Trump advocated closing the border to Muslims.

Third, party polarization heightens the power of partisan identities, often increasing dislike of the “other” party and the sense of threat that party poses, while encouraging heightened in-group loyalty and differentiation from the out-group. Party identifiers have strongly negative views and low affect toward out-partisans (e.g., Iyengar et al., 2012). Those attitudes may make people with partisan identities less likely to adopt a position associated with out-partisans. Negative views of out-partisans can further motivate people to maintain existing attitudes by discounting or arguing against challenging information (e.g., Taber & Lodge, 2006). Partisans motivated to maintain their favorable views of party elites may reject even the most compelling of frames when they oppose the party’s views (Druckman et al., 2013).

Fourth, as noted, among evangelicals, identification with the Republican Party and President Trump is especially strong. Analyses looking for evidence of cross-pressure among white evangelical Republicans in the 2016 election found little (Cassese, 2020; Margolis, 2020). Given strong ties between many evangelicals and Trump, any frame that conflicts with a Trump position, which at least implicitly links the frame to out-groups, may be met with resistance.

Yet, although party identities wield tremendous power, that power is not absolute (e.g., Boudreau & MacKenzie, 2014; Klar, 2013; Peterson, 2019). Counter-partisan messages framed in terms of moral values prioritized by conservatives (liberals) can shift attitudes away from Republican (Democratic) Party positions (e.g., Bayes et al., 2020; Feinberg & Willer, 2015; Wolsko et al., 2016). For example, framing environmental protection as a patriotic way to protect the purity of natural resources (conservatives prioritize patriotism and purity) increases conservatives’ pro-environmental attitudes (Bayes et al., 2020; Wolsko et al., 2016).

Frames expressing explicitly religious values hold the potential to shift attitudes away from party positions as well (Djupe & Smith, 2019). Previous work shows framing by religious elites is most effective when frames tap into core values central to a particular religious tradition (DeMora et al., 2021; Djupe & Calfano, 2013), when elites refer to the process by which they reached their political decisions (Djupe & Gwiasda, 2010), and when frames point to consensus among the religious group’s leaders (Campbell & Monson, 2003). Furthermore, frames offered by trusted sources tend to be powerful (e.g., Druckman, 2001) and many evangelicals trust the clergy of their church in a variety of ways (Pew Research Center, 2019). Consequently, at least under some conditions, religious frames may counteract partisanship.

In fact, a few studies have found that religious leaders’ messages on immigration can affect co-religionists’ attitudes. For example, Wallsten and Nteta (2016) found Southern Baptists exposed to a pro-immigration reform message from a Southern Baptist leader were more favorable to reform than a control group not exposed to the message (see also Nteta & Wallsten, 2012). In addition, Margolis (2018a, 778) found that exposure to a radio advertisement aired by the Evangelical Immigration Table, in which two pastors asked listeners to support “immigration reform rooted in biblical values,” led to greater support for immigration reform among white evangelicals. Moreover, values and religion often play a key role in attitudes about refugees, suggesting religious value frames may have resonance in this domain (e.g.Adida et al., 2019; Fraser & Murakami, 2021; Melkonian-Hoover & Kellstedt, 2019; Nassar, 2020a, b; Newman, 2018; Wong, 2018).

We build on these studies in several ways. First, we examine whether religious framing that runs counter to a party position can shape opinion in the Trump era. Margolis (2018a) found evangelicals responded to an evangelical pro-immigration reform ad in 2014, not long after a bipartisan group of Senators drafted an immigration reform bill that passed the Senate with 14 Republican votes. Immigration issues, including refugee policy, became more polarized along party lines during the Trump presidency (Ferwerda et al., 2017; Hartig, 2018; Hoewe, 2018). In a context of increased party polarization over immigration, white evangelicals may be especially unwilling to adopt a view associated with out-groups (e.g., liberals, Democrats, and certain racial/ethnic minority groups). This context creates a tough test of the ability of a religious frame to move opinion on refugees.

Second, we explore in greater depth the power of religious source cues. Wolsko et al. (2016) found a moral values message was especially powerful when participants perceived the frame to come from an in-group source. However, their study did not directly manipulate source cues. In a field experiment, Margolis (2018a) found that a pro-reform advertisement from a religious source was more effective in getting people to open an email about immigration reform than a secular advertisement stripped of any religious content. However, the religious and secular ads differed on multiple dimensions, not just source cue. It remains unclear how much influence in-group message content or in-group source cues alone hold for opinion; our study drills down into this question.

Third, we consider the moderating effect of identity strength in the context of cross-pressure. Within social identity theory, the strength of a particular identity drives individuals’ responses to a perceived threat to one’s group (e.g., Huddy et al., 2015). If we view Republican and evangelical identities from this perspective (e.g., Greene, 2004; Miles, 2019; Margolis, 2020; Wilcox et al., 2016 [1993]), people who more strongly identify as Republican and/or evangelical have a stronger motivation to protect and advance the status of these groups. Therefore, they may be more likely to align their attitudes with the group when they encounter a clear group position on an issue. If an evangelical message runs counter to a Republican position, identity strength may condition the individuals’ reaction such that a person who strongly identifies as a Republican ought to be more likely to reject the religious challenge to her partisan position. However, a person who strongly identifies as an evangelical may be more likely to move opinions in closer alignment with her evangelical identity (see Groenendyk, 2013). In short, when messages linked to dual religious and partisan identities conflict, strength of identity ought to condition the relationship between messages and attitudes.

From this discussion, we derive four pre-registered hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1

White evangelical Republicans encountering a religious values frame promoting greater acceptance of refugees will support refugee resettlement more than other white evangelical Republicans.

Hypothesis 2

A pro-refugee religious values frame with an in-group source cue will have a larger impact on white evangelical Republicans than such frames without a source cue.

Hypothesis 3

A pro-refugee religious values frame will have a greater impact on white evangelical Republicans who more strongly identify with evangelicals.

Hypothesis 4

A pro-refugee religious values frame will have less impact on white evangelical Republicans who more strongly identify with Republicans.Footnote 3

Our target sample for the hypotheses is self-identified white evangelical Republicans. Studies of evangelicals tend to employ one of three approaches to measuring evangelicals (see e.g., Burge & Lewis, 2018; Margolis, 2020; Smidt, 2019). Since we are operating in the context of social identity theory, conceptualizing evangelicalism as a social identity (e.g., Margolis, 2018a; Miles, 2019; Penning, 2009), we focus on people who self-identify as an “evangelical or born again Christian” (Burge & Lewis, 2018; see Appendix B for additional discussion). We recognize that religion’s political influence operates in various ways and other conceptualization and measurement strategies offer important insights. We use the strategy that most closely matches our theoretical approach and has been employed in various religion and politics studies (e.g., Allen & Olson, 2022; Burge & Lewis, 2018; Cassese, 2020; Castle & Stepp, 2021; Claassen et al., 2021).

An Experiment to Assess the Religious Values Frame

Given the power of partisanship, only the most compelling of religious value frames are viable candidates to move white evangelical Republican opinion away from the party line. Consequently, we fielded a pilot study in January 2020 to test the effectiveness of different messages among white self-identified evangelicals. Respondents evaluated the direction (whether the argument was in support or opposition) and effectiveness of 20 messages related to refugees (see Appendix A for details). We identified one religious values frame in support of refugees that was particularly strong to use in our experiment. This frame quotes from part of the pro-refugee open letter signed by many evangelical leaders mentioned above, increasing external validity.

The experiment contains three randomly assigned conditions: religious values frame (Religious Values), religious values frame with source cue (Religious Values + Source Cue), and control. See Table 1 for the treatment text. Note that the text from the two treatments is identical except for the source cue, and the sources are those who wrote or signed the open-letter in the Washington Post. We intentionally mask the treatment to minimize experimenter demand effects (see discussion in De Quidt et al., 2018; Mummolo & Peterson, 2019). Thus, the treatments appear unobtrusively within a standard opinion module and those in the treated conditions are asked two questions about the frame.

Subjects are first asked: “Regardless of the source, is this a message that you have heard previously?” (yes/no). Second, “To what extent do you agree or disagree with the message?” (5-point strongly disagree to strongly agree scale). Among the participants in our study who received these questions, 77% said that they had heard this message previously. The high percentage of people who had heard the message prior to the study could result in a saturation effect. Saturation could explain null effects, as noted in our pre-registration. In addition, 75% agreed or strongly agreed with the message, giving us confidence that the message connected with the religious values of many white evangelical Republicans. The control condition receives no frame and neither of these two follow-up questions. The design maximizes on internal validity (avoiding demand effects) and external validity (presenting information in a conversational manner), yet strictly speaking it means the treatment consists of a message plus two questions that prompt the respondent to reflect on the message (for a similar approach, see e.g., Lahav & Courtemanche, 2012).

Sample

The sample was collected from August 14–24, 2020, by YouGov, who invited panelists who previously self-identified as white and evangelical to take a survey.Footnote 4 The sample (N = 1,500) was drawn to be nationally representative of this subpopulation by matching to characteristics in the 2014 Pew Religious Landscape Survey dataset. We trim the dataset to include only those who identify as white, evangelical, and Republican, leaving us with a sample of 791 respondents.Footnote 5 In our pre-analysis plan, we set thresholds for excluding speeders based on average reading time, which trims the sample to 682 respondents (see Appendix for details and results including speeders). See Appendix Table 1 for weighted descriptive statistics on the sample. Respondents were evenly distributed across experimental conditions according to a range of demographic measures and political dispositions (see Appendix Table 2).Footnote 6

Core Measures

The post-treatment survey includes measures of affect toward refugees, attitudes toward refugee resettlement in the U.S., and attitudes toward government support for refugees already in the U.S. To measure affect toward refugees, subjects were asked a battery of feeling thermometer questions, including toward “refugees.” To further mask the intention of the study, we asked about eight groups, with the order of these groups randomized.Footnote 7

Two items measure attitudes toward refugee resettlement. The first asked whether respondents support or oppose refugee resettlement in their local community, while the second asked if they support or oppose refugee resettlement in the United States (Ferwerda et al., 2017). Response options are on a 5-point scale from strongly oppose to strongly support. We combine these into a single “Resettlement” measure that runs from 0 to 1 (alpha = 0.92).

To measure attitudes toward policies supporting refugees who are already in the U.S., we asked the extent to which respondents agree or disagree with the following two statements: (1) children of refugees already in the U.S. should be allowed to study in public schools; and, (2) refugees should not be eligible for unemployment benefits. Both have five-point strongly disagree to strongly agree response options, and we reverse coded the second question to be more supportive of unemployment benefits. The alpha score for these two measures is low (alpha = 0.37), so we consider them separately.

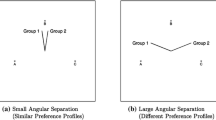

To measure partisan identity strength, we used Greene’s (2004) 10 item partisan identity strength battery. We then adapted the items to create a measure of evangelical identity strength (See Appendix B for item wording). The evangelical identity strength items yield a high scale reliability (alpha = 0.80), so we combine those responses into an additive index. Participants with higher levels of evangelical identity strength report higher levels of church attendance and prayer (see Appendix B), providing confidence in the measure’s validity. The Republican identity strength items also have high scale reliability (alpha = 0.75), so we combine those responses into an additive index. We plot the distribution of the evangelical and Republican identity strength measures below (see Fig. 1). There is a great deal of overlap in the strength of these identities (Pearson correlation = 0.50), with both resembling a normal distribution, and Republican identity being slightly stronger than evangelical identity. This pattern of findings is consistent with the arguments made about social sorting in the electorate (Layman, 2001; Mason, 2018), but also shows that the strength of these overlapping identities varies across individuals. That we find such a wide spread in identity attachments reinforces our argument that it is important to consider heterogeneous reactions to religious values messages.

Results of the Religious Values Framing Experiment

To test our first hypothesis (H1), we regress the dependent variables on dummy measures for each treatment condition (the baseline is the control condition). The results are presented in Table 2. We start with the treatment without a source cue. Self-identified white evangelical Republicans who are presented with a religious values frame feel about 11 points warmer toward refugees compared to the control group (p < 0.01), who rated refugees just below the neutral point at 47 on average. In addition, those in the religious values condition were somewhat more favorable toward resettling refugees in the U.S., with a mean 0.05 higher than the control group’s mean of 0.33 on the 0–1 scale (p < 0.10, two-tailed). In contrast, the treatment did not increase support for government benefits to refugees: we find no positive effects for the schooling and unemployment benefits items.

The treatment with an evangelical source cue had a similar effect on the refugee feeling thermometer (p < 0.01). On average, participants in this condition rated refugees about 7 points warmer than the control group. Although the estimated treatment effect is positive for attitudes about resettlement, it falls short of statistical significance. Once again, there was no treatment effect on attitudes toward schooling refugee children, while there is actually some backlash on attitudes toward providing unemployment benefits to refugees (p < 0.05). To put this in perspective, about 12% of the control condition favored providing unemployment benefits to refugees, whereas only 9% supported this in the Religious Values + Source Cue condition.

In short, the treatments boost feelings of warmth toward refugees and (in one case) support for resettlement, yet they stop short from moving respondents toward supporting the provision of public benefits for refugees. We interpret the results as supporting H1: the religious message moved self-identified evangelicals’ opinion in a pro-refugee direction. However, there are limits. We can think of two non-rival reasons for divergence across dependent variables. First, the treatment does not mention government policy, potentially constraining its effectiveness to more general support for refugees. Second, self-identified evangelical Republicans tend to be politically conservative, favoring small government,Footnote 8 which may lead individuals to prefer to support refugees via non-governmental options like non-profits and churches, and this may have been particularly salient in the condition with a religious source cue.

Hypothesis 2 (H2) is that the Religious Values + Source Cue message will have a larger impact on white evangelical Republicans than the Religious Values frame without a source cue. We assess this by testing whether attitudes differ between these conditions. In brief, we do not find support for H2 (results available in Appendix Table 4). The evangelical source cue did not boost the effect of the religious values message.

Hypothesis 3 (H3) posits that pro-refugee religious values frames will have a greater effect on people who more strongly identify with evangelicals. We test this via a series of OLS regression analyses with the same dependent variables. The independent variables are dummy variables for treatment, the strength of evangelical identity measure, and interactions between the treatments and evangelical identity strength. We control for the strength of partisan identity. Figure 2 shows the estimated treatment effects at varying levels of evangelical identity strength, along with 90% confidence bars (see Appendix Table 5 for regression results). Looking first at the treatment with a source cue (the top half of the figure), we see that the treatment effects are stronger for participants with higher levels of evangelical identity strength. People in this condition with low identity strength had feeling thermometer ratings lower or indistinguishable from the control group (the confidence bars include zero in most cases), while people with higher evangelical identity strength rated refugees significantly higher than the control group. These treatment effects are also quite substantial, as high as 24.9 degrees, for those at the highest level of evangelical identity strength. For resettlement attitudes, the treatment had no effect at low levels of evangelical identity strength, but a positive effect, ranging from 0.03 to 0.11 at higher levels of evangelical identity. There is no discernable treatment effect at any level of evangelical identity strength for attitudes toward schooling. Finally, we see the backlash against the treatment with source cue on attitudes toward unemployment benefits is concentrated among those with low evangelical identity strength.

We see similar patterns for the treatment without an evangelical source cue (the bottom half of the figure). This treatment had no discernable effect on the refugee feeling thermometer for those with low levels of identity strength, but a positive effect for those with stronger identity strength (up to 20.3 degrees above the control group average). The same is true for resettlement attitudes (though at the highest levels, with few observations, the confidence bars elongate). There is no discernable treatment effect on attitudes toward schooling or unemployment benefits. In sum, we find support for H3 on our outcome measures of feelings toward refugees and views toward resettlement.

Hypothesis 4 (H4) posits that pro-refugee religious values frames will have less impact on self-identified white evangelical Republicans who more strongly identify as Republicans. We test this by running a series of OLS regressions with the same dependent variables and dummy variables for the treatments and an interaction between each treatment and the measure of Republican identity strength. We also control for strength of evangelical identity. Figure 3 presents the results (see Appendix Table 6 for regression results).

We find no support for H4. In fact, the results run counter to the hypothesis in some instances. Looking first at the treatment with a source cue in the top half of the figure, we see that the treatment effect for the feeling thermometer rating is indistinguishable from zero at low levels of Republican identity strength, but is significant and positive at higher levels of Republican identity strength. A similar pattern appears for attitudes toward resettlement. There is no discernable treatment effect for attitudes toward schooling and unemployment at any level of Republican identity strength.

Turning to the treatment without a source cue, we observe similar patterns. There is no treatment effect for feeling thermometer ratings among participants with low Republican identity strength. But Republicans with greater Republican identity strength who were in the religious values condition rate refugees significantly more warmly than Republicans in the control condition, opposite our expectations. Along similar lines, attitudes toward resettlement are unaffected by the treatment for those with lower levels of Republican identity strength, but at higher levels the treatment exerts a significant positive effect, until the highest levels with few observations and longer confidence bands. There are no discernable treatment effects for the schooling and unemployment items. In sum, contrary to H4, those with higher levels of Republican identity strength did not react against the evangelical treatment that ran counter to the Republican position. In fact, they moved away from the Republican position toward more positive attitudes toward refugees and refugee resettlement.

Robustness Checks

We conducted several robustness checks on the core findings. We ran analyses including speeders (Appendix Tables 9, 10 and 11; Figs. 4 and 5); the results remain largely consistent. We ran supplemental analyses to assess and account for an additional experiment embedded within our survey, in which the resettlement question was presented in one of three ways: on its own, primed with a statement about a lack of major COVID-19 cases in refugee camps, or primed with a statement about COVID-19 in refugee camps. Our conclusions hold in analyses that account for that experiment (see Appendix Tables 12, 13 and 14). We assessed the robustness of our results regarding evangelical identity with an alternative measure, as pre-registered (see Appendix Table 14; Fig. 6). A single identity strength measure does not perform as well as the index. While there were no significant interactions between this alternate measure and our treatments, there were several significant marginal effects among those scoring highest in evangelical identity. Furthermore, we ran the analyses shown here without identity controls in Appendix Tables 15 and 16, and Appendix Figs. 7 and 8; we find a similar pattern of results. Finally, we ran our primary analyses with demographic controls (e.g., education, age, gender, and income) in addition to the alternate identity control included here (see Appendix Tables 17, 18 and 19). Core conclusions remain unchanged in models with these controls.

Extension to Non-Evangelical Groups

Are the reactions we observe among white evangelical Republicans unique to that subgroup within the U.S. population? As an extension, we consider how non-evangelicals react to this type of religious values messaging. Earlier work finds messaging sometimes produces backlash, moving opinion in the opposite direction of the message (e.g., Merkley & Stecula, 2021; Nyhan & Reifler, 2010; Pink et al., 2021). If religious values messaging pushes many non-evangelicals in the opposite direction, such messaging may produce a net negative effect on support for refugees. To explore this question, we ran our experiment on the 2020 Cooperative Election Study.Footnote 9 The nationally representative sample included 1,000 subjects, of which 730 are non-evangelicals. Table 3 shows the results for the core experiment for this sample.

Table 3 shows, first, that the religious values frame has a positive and significant effect on support for resettling refugees, but that treatment has no effect for the other three dependent variables. Second, the message with a source cue elicits less support for refugee unemployment benefits, as in our main experiment.Footnote 10 Overall, appeals to religious values do little to shift the opinions of non-evangelicals, suggesting the messages do not produce strong backlash. While the religious values frame may reduce support for unemployment benefits when delivered with an evangelical source cue, we found this among evangelicals in the core experiment, and the non-evangelical population sometimes responds positively (on the issue of resettlement) when exposed to a religious values frame.

Conclusion

We provide evidence that religious values framing can nudge self-identified white evangelical Republicans’ opinions away from the party line on refugees. While some earlier studies found religious messages can shift evangelicals’ views on immigration in a somewhat more bipartisan era (Margolis, 2018a; Wallsten and Nteda, 2016), our results show this is even true in the Trump era, a highly partisan environment in which partisanship has seemed to dominate all other potential influences on political attitudes, and among a group highly supportive of Trump. Even people with strong Republican identities have more favorable attitudes toward refugees and refugee resettlement in the U.S. after seeing the religious values message, moving away from the clear partisan position on refugees. Religious values frames, like other moral values frames (e.g., DeMora et al., 2021; Feinberg & Willer, 2013, 2015; Wolsko et al., 2016), could help bridge at least part of the partisan divide on this issue, potentially reshaping the national discussion on refugees.

Our study extends work on moral reframing to the topic of refugees, and creates a “hard test” by focusing on self-identified white evangelical Republicans, who have predominantly toed the Republican line on this policy. In our sample, many identify strongly with their religious community (67% in our sample scored 0.5 or above on the 0–1 evangelical identity strength scale), meaning many could be open to counter-Republican religious values frames, at least on some questions. Moreover, even among self-identified white evangelicals who strongly identify with the Republican Party, the religious values frame moved attitudes away from the restrictionist Republican position. Counter-attitudinal or counter-partisan messages can sometimes lead to backlash, strengthening current attitudes (e.g., Nyhan & Reifler, 2010). The results in Fig. 3 suggest that, controlling for strength of evangelical identification, stronger identification with the Republican Party did not generate backlash. These findings, along with those from a national sample, show the potential for religious values frames that run counter to partisan positions to shift some people’s views away from partisan positions without producing backlash among partisans or non-evangelicals.

Our results point to some of the contours of religious values framing effects. Some attitudes are more pliable than others: the religious values message increased warmth toward refugees and support for resettlement, but did not alter white evangelical Christians’ stances on providing government resources to support this group. An in-group (evangelical leader) source cue did not increase the impact of the religious values message and produced a bit of backlash in the case of providing unemployment benefits to refugees. In addition, the message’s impact, delivered with or without a source, was greatest among those who strongly identify as evangelical.

Evidence that the message’s impact varies points to the importance of examining additional factors that might condition the effect of moral messages. Future research should do more to theorize over which attitudes are most and least susceptible to values framing effects that run counter to partisanship. In addition, future work should explore how religious messaging’s effects vary (1) with traits of the refugees in question, (2) traits of the individuals receiving the message, and (3) the context of the message. Scholars have found that opinions toward refugees vary according to perceptions of their religious and cultural backgrounds (Adida et al., 2019; Filindra et al., 2022; Nassar, 2020b; see also Roy, 2023). Our study asked about attitudes toward refugees in general. Because Syrian refugees were salient at the time of our study, presumably some people were thinking about this particular group when answering our questions, and they likely assumed Muslim refugees.Footnote 11 Future research should more systematically assess connections among elite cues, religious values, and the background of refugees. For example, are the positive effects of religious values frames more muted for Muslim refugees compared to Christian refugees? Are they more muted for those seeking asylum from Latin America compared to other countries? Are religious values messages even more effective for people fleeing Ukraine? Do these messages also increase support for those who are not refugees, but migrants?

Our study makes a contribution by highlighting that the strength of social identities can moderate the impact of religious values framing. Future research on the role of groups in shaping political attitudes should continue to take strength of identities into account. In addition, while our focus has been on identities, future research should also consider other potential individual-level moderators, such as empathy, anger, threat, and lived experience.

We hope that future research will also explore how the context of a moral values message modifies the impact of the message. We suspect much of Republicans’ openness to our religious values message would disappear if these partisans were also exposed to a partisan frame supporting restrictive policy. A limitation of our study is that we cannot compare the effectiveness of the pro-refugee religious frame against an anti-refugee message adopting either a partisan or religious frame. Our approach mirrors other studies that only look at either a positive or a negative message, respectively (see e.g., Lahav & Courtemanche, 2012) and it fits our interest in examining messages that relate to dueling identities. Yet, given that multiple frames are part of the information environment, comparisons like these are central to any future research agenda. What the current results reveal is that strong Republicans may be more open to attitude change than popular imagination seems to appreciate. This could be because these strongly identifying Republicans are starting from a very low bar of support for refugees and therefore have a lot of room to move. Future research should explore the conditions under which strong identifiers are open to shifting away from the party line.

One additional limitation of our present study that future work should take up relates to source cues for religious frames. We consider these religious values frames a subtype of moral values frames; however, unlike general secular moral frames (e.g., an appeal to patriotism), our message makes explicit reference to Jesus. Many religious frames targeted at evangelicals invoke Jesus, and our approach thus increases external validity. However, our design cannot pinpoint the degree to which the treatment effects stem from highlighting religious values or from referencing Jesus. Future scholarship should consider whether moral or religious values frames that reference the teachings of specific people (e.g., Jesus, Gandhi, Muhammad) are more powerful than frames that reference morals alone. In brief, there is a broad agenda for scholars to tackle when it comes to revealing the ways that religious values frames shape opinion.

Finally, one factor to take into consideration when drawing inferences from our results is that the vast majority of the participants indicated that they were already familiar with the treatment, potentially muting message effects. If this is the case, then it speaks to the challenge that moral messages face in moving opinion among this population. Despite having heard this message before, baseline attitudes remain fairly cool and largely restrictionist when it comes to refugees. Partisan inclinations may often trump awareness of or emphasis on religious dimensions of policy issues. In this case self-identified white evangelical Republicans may have previously heard that Jesus was a refugee who cared for similarly vulnerable individuals and called his followers to do the same, but that message may be drowned out by partisan sources articulating restrictionist perspectives. And, thus, our study shows both the potential and the limits of religious values messages when it comes to opinion on key partisan issues.

Data Availability

Replication data for this research can be found in the Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QYZQ4Y.

Notes

See https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/us-annual-refugee-resettlement-ceilings-and-number-refugees-admitted-united. The cap for 2021 was subsequently raised by the Biden administration. Trump’s executive order also suspended all refugee admissions for 120 days and barred travel to the U.S. for 90 days for individuals from seven Muslim majority nations. After this order, refugee admissions declined substantially, but Christians made up a larger percentage of refugees admitted than Muslim refugees (Connor & Krogstad, 2018). For full text of the executive order: https://www.cnn.com/2017/01/28/politics/text-of-trump-executive-order-nation-ban-refugees/index.html.

We use messages and frames interchangeably. Messages can contain information other than frames; however, the particular messaging that we examine involves the communication of frames that emphasize religious values. Druckman (2001) offers a cogent conceptualization of frames and framing effects in political messaging.

These hypotheses were pre-registered with this exact wording, with two exceptions: to be more faithful to the design, we changed “religious values frames” from plural to singular and we added “Republicans” to H1-3 to be consistent with the pre-registered research question: “Although Republican and white evangelical identities often work in tandem, what happens when they conflict?”. We also pre-registered a fifth hypothesis, which mirrors H4 but refers to support for Donald Trump. By design, the core measures of support for Trump were asked post-treatment, which confounds the hypothesis test. We assess this hypothesis in the appendix (Tables 7 and 8; Figure 2) and find a similar pattern to what we show for H4. The pre-registration also noted two exploratory avenues for research –moderating effects of dispositional empathy and lived experience; these will be assessed in separate work.

Evangelical self-identity was measured in a two-question module following Burge and Lewis (2018). First, respondents were asked “What is your present religion, if any?” Respondents who selected Protestant, Roman Catholic, Mormon, Eastern or Greek Orthodox, or “Something else” were asked a follow up question: “Would you describe yourself as a “born-again” or evangelical Christian, or not?” Those who respond Protestant and “Yes” were coded as evangelical, as were those who said, “Something else”, identified a Protestant tradition in the follow-up question, and said “Yes.” Following Burge and Lewis (2018), Catholic and LDS respondents were excluded from the evangelical category.

The survey design was fairly effective in achieving the intended sample. Only 30 respondents identified as non-white, and 288 as non-Evangelical (these are individuals who identified as white or evangelical in a previous survey but did not identify as such in our survey). We drop 479 non-Republicans but retain Republican leaning independents.

The weights we use are not broadly nationally representative but are specific to the white born-again Christian population as estimated by Pew.

For analyses on feelings towards other groups see Appendix Table 3.

For details on this study’s methods, see https://cces.gov.harvard.edu/.

The results are similar if we restrict the analysis to white respondents who do not identify as evangelical (see Appendix Table 20). We do not have sufficient observations (statistical power) to run other analyses, for example, on evangelical-identifying individuals in the CES dataset.

References

Adida, C. L., Lo, A., & Platas, M. R. (2019). Americans preferred Syrian refugees who are female, English-speaking, and Christian on the eve of Donald Trump’s election. PloS ONE, 14(10), e0222504. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222504

Adida, C. L., Lo, A., & Platas, M. R. (2018). Perspective taking can promote short-term inclusionary behavior toward Syrian refugees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 115(38), 9521–9526. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1804002115

Allen, L. G., & Olson, S. F. (2022). Racial attitudes and political preferences among black and white evangelicals. Politics and Religion, 15(4), 631–648. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048322000074

Barber, M., & Pope, J. C. (2019). Does party trump ideology? Disentangling party and ideology in America. American Political Science Review, 113(1), 38–54. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000795

Bayes, R., Druckman, J. N., Goods, A., & Molden, D. C. (2020). When and how different motives can drive motivated political reasoning. Political Psychology, 41(5), 1031–1052. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12663

Blake, A. (2016). The final Trump-Clinton debate transcript, annotated. The Washington Post Retrieved August 21, 2023, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2016/10/19/the-final-trump-clinton-debate-transcript-annotated

Boudreau, C., & MacKenzie, S. A. (2014). Informing the electorate? How party cues and policy information affect public opinion about initiatives. American Journal of Political Science, 58(1), 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12054

Burge, R. (2021). The 2020 Vote for President by Religious Groups—Christians. Retrieved February 5, from https://religioninpublic.blog/2021/03/29/the-2020-vote-for-president-by-religious-groups-christians/

Burge, R. P., & Lewis, A. R. (2018). Measuring evangelicals: Practical considerations for social scientists. Politics and Religion, 11(4), 745–759. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048318000299

Calfano, B., & Djupe, P. (2013). God talk: Experimenting with the religious causes of public opinion. Temple University Press.

Campbell, D. E., & Monson, J. Q. (2003). Following the leader? Mormon voting on ballot propositions. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 42(4), 605–619. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-5906.2003.00206.x

Campbell, D. E., Layman, G. C., Green, J. C., & Sumaktoyo, N. G. (2018). Putting politics first: The impact of politics on American religious and secular orientations. American Journal of Political Science, 62(3), 551–565. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12365

Cassese, E. C. (2020). Straying from the flock? A look at how americans’ gender and religious identities cross-pressure partisanship. Political Research Quarterly, 73(1), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912919889681

Castle, J. J., & Stepp, K. K. (2021). Partisanship, religion, and issue polarization in the United States: A reassessment. Political Behavior, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09668-5

Claassen, R. L., Djupe, P. A., Lewis, A. R., & Neiheisel, J. R. (2021). Which party represents my group? The group foundations of partisan choice and polarization. Political Behavior, 43, 615–636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09565-6

Collingwood, L., Lajevardi, N., & Oskooii, K. A. (2018). A change of heart? Why individual-level public opinion shifted against Trump’s Muslim Ban. Political Behavior, 40, 1035–1072. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-017-9439-z

Connor, P., & Krogstad, J. M. (2018). The number of refugees admitted to the U.S. has fallen, especially among Muslims. Pew Research Center. Retrieved August 21, 2023, from https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2018/05/03/the-number-of-refugees-admitted-to-the-u-s-has-fallen-especially-among-muslims/

De Quidt, J., Haushofer, J., & Roth, C. (2018). Measuring and bounding experimenter demand. American Economic Review, 108(11), 3266–3302. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20171330

DeMora, S. L., Merolla, J. L., Newman, B., & Zechmeister, E. J. (2021). Reducing mask resistance among White evangelical christians with value-consistent messages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(21), e2101723118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.210172311

Djupe, P. A., & Gwiasda, G. W. (2010). Evangelizing the environment: Decision process effects in political persuasion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 49(1), 73–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5906.2009.01493.x

Djupe, P. A., & Smith, A. E. (2019). Experimentation in the study of religion and politics. In Oxford research encyclopedia of politics. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.990

Druckman, J. N. (2001). The implications of framing effects for citizen competence. Political Behavior, 23, 225–256. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015006907312

Druckman, J. N., Peterson, E., & Slothuus, R. (2013). How elite partisan polarization affects public opinion formation. American Political Science Review, 107(1), 57–79. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055412000500

Feinberg, M., & Willer, R. (2013). The moral roots of environmental attitudes. Psychological Science, 24(1), 56–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612449177

Feinberg, M., & Willer, R. (2015). From gulf to bridge: When do moral arguments facilitate political influence? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(12), 1665–1681. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167215607842

Feinberg, M., & Willer, R. (2019). Moral reframing: A technique for effective and persuasive communication across political divides. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 13(12), e12501. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12501

Ferwerda, J., Flynn, D. J., & Horiuchi, Y. (2017). Explaining opposition to refugee resettlement: The role of NIMBYism and perceived threats. Science Advances, 3(9), e1700812. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1700812

Filindra, A., Nassar, R. L., & Buyuker, B. E. (202). The conditional relationship between cultural and economic threats in white americans’ support for refugee relocation programs. Social Science Quarterly, 103(3), 686–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.13151

Fraser, N. A., & Murakami, G. (2021). The role of humanitarianism in shaping public attitudes toward refugees. Political Psychology, 43(2), 255–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12751

Green, D. P., Palmquist, B., & Schickler, E. (2002). Partisan hearts and minds: Political parties and the social identities of voters. Yale University Press.

Greene, S. (2004). Social identity theory and party identification. Social Science Quarterly, 85(1), 136–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0038-4941.2004.08501010.x

Groenendyk, E. (2013). Competing motives in the partisan mind: How loyalty and responsiveness shape party identification and democracy. OUP USA.

Hainmueller, J., & Hopkins, D. J. (2014). Public attitudes toward immigration. Annual Review of Political Science, 17, 225–249. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-102512-194818

Hartig, H. (2018). Republicans Turn More Negative toward Refugees as Number Admitted to U.S. Plummets. Retrieved February 5, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/05/24/republicans-turn-more-negative-toward-refugees-as-number-admitted-to-u-s-plummets/

Haynes, C., Merolla, J. L., & Ramakrishnan, S. K. (2016). Framing immigrants: News Coverage, Public Opinion, and policy. Russell Sage Foundaiton.

Hoewe, J. (2018). Coverage of a crisis: The effects of international news portrayals of refugees and misuse of the term immigrant. American Behavioral Scientist, 62(4), 478–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764218759579

Huddy, L., Mason, L., & Aarøe, L. (2015). Expressive partisanship: Campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. American Political Science Review, 109(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055414000604

Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(3), 405–431. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfs059

Jones, R. P., Cox, D., Griffin, R. & Najle, M. (2018). Partisan polarization dominates the Trump era: Findings from the 2018 American Values Survey. PRRI. https://www.prri.org/research/partisan-polarization-dominates-trump-era-findings-from-the-2018-american-values-survey/

Klar, S. (2013). The influence of competing identity primes on political preferences. Journal of Politics, 75(4), 1108–1124. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381613000698

Lahav, G., & Courtemanche, M. (2012). The ideological effects of framing threat on immigration and civil liberties. Political Behavior, 34, 477–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-011-9171-z

Layman, G. (2001). The great divide: Religious and cultural conflict in American party politics. Columbia University Press.

Lenz, G. S. (2013). Follow the leader? How voters respond to politicians’ policies and performance. University of Chicago Press.

Levendusky, M. S. (2009). The microfoundations of mass polarization. Political Analysis, 17(2), 162–176. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpp003

Margolis, M. F. (2018a). How far does social group influence reach? Identities, elites, and immigration attitudes. Journal of Politics, 80(3), 772–785. https://doi.org/10.1086/693985

Margolis, M. F. (2018b). From politics to the pews: How partisanship and the political environment shape religious identity. University of Chicago Press.

Margolis, M. F. (2020). Who wants to make America great again? Understanding evangelical support for Donald Trump. Politics and Religion, 13(1), 89–118. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048319000208

Mason, L. (2018). Uncivil agreement: How politics became our identity. University of Chicago Press.

Mason, L., & Wronski, J. (2018). One tribe to bind them all: How our social group attachments strengthen partisanship. Political Psychology, 39, 257–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12485

Mason, L., Wronski, J., & Kane, J. V. (2021). Activating animus: The uniquely social roots of Trump support. American Political Science Review, 115(4), 1508–1516. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000563

Melkonian-Hoover, R. M., & Kellstedt, L. A. (2019). Evangelicals and immigration: Fault lines among the faithful. Springer International Publishing.

Merkley, E., & Stecula, D. A. (2021). Party cues in the news: Democratic elites, republican backlash, and the dynamics of climate skepticism. British Journal of Political Science, 51(4), 1439–1456. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000113

Miles, M. R. (2019). Religious identity in US politics. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Miller, E. M. (2017). 500 Prominent Evangelicals Take Out Full-page Ad Supporting Refugees. Religion News Service. Retrieved July 14, 2022, from https://religionnews.com/2017/02/09/500-prominent-evangelicals-take-out-full-page-ad-supporting-refugees/

Mummolo, J., & Peterson, E. (2019). Demand effects in survey experiments: An empirical assessment. American Political Science Review, 113(2), 517–529. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000837

Nassar, R. (2020a). Threat, prejudice, and white americans’ attitudes toward immigration and Syrian refugee resettlement. Journal of Race Ethnicity and Politics, 5(1), 196–220. https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2019.37

Nassar, R. (2020b). Framing refugees: The impact of religious frames on US partisans and consumers of cable news media. Political Communication, 37(5), 593–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1723753

Newman, B. (2018). Who supports syrians? The relative importance of religion, partisanship, and partisan news. PS: Political Science & Politics, 51(4), 775–781. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096518000562

Nteta, T. M., & Wallsten, K. J. (2012). Preaching to the choir? Religious leaders and American opinion on immigration reform. Social Science Quarterly, 93(4), 891–910. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2012.00865.x

Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2010). When corrections fail: The persistence of political misperceptions. Political Behavior, 32(2), 303–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9112-2

Oskooii, K. A., Lajevardi, N., & Collingwood, L. (2021). Opinion shift and stability: The information environment and long-lasting opposition to Trump’s Muslim ban. Political Behavior, 43, 301–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09555-8

Penning, J. M. (2009). Americans’ views of muslims and mormons: A social identity theory approach. Politics and Religion, 2(2), 277–302. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048309000236

Peterson, E. (2019). The scope of partisan influence on policy opinion. Political Psychology, 40(2), 335–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12495

Pew Research Center (2019). Americans have positive views about religion’s role in society, but want it out of politics. Retrieved February 5, 2022, from https://www.pewforum.org/2019/11/15/americans-have-positive-views-about-religions-role-in-society-but-want-it-out-of-politics/

Pink, S. L., Chu, J., Druckman, J. N., Rand, D. G., & Willer, R. (2021). Elite party cues increase vaccination intentions among Republicans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(32), e2106559118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2106559118

Roy, O. (2023). Evangelical attitudes toward Syrian refugees: Are evangelicals distinctive in their opposition to Syrian refugees to the United States? Politics and Religion. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048323000214

Shaheen, J. G. (2003). Reel bad arabs: How Hollywood vilifies a people. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 588(1), 171–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716203588001011

Skinner, I. W. (2022). How characterizations of refugees shape attitudes toward refugee restrictions: A study of Christian and Muslim americans. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 34(3), edac022. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edac022

Smidt, C. E. (2019). Reassessing the concept and measurement of evangelicals: The case for the RELTRAD approach. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 58(4), 833–853. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12633

Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 755–769. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00214.x

Taylor, J. (2015). Trump calls for ‘total and complete shutdown of Muslims enter’ U.S. NPR Retrieved August 21, 2023, from https://www.npr.org/2015/12/07/458836388/trump-calls-for-total-and-complete-shutdown-of-muslims-entering-u-s

Wallsten, K., & Nteta, T. M. (2016). For you were strangers in the land of Egypt: Clergy, religiosity, and public opinion toward immigration reform in the United States. Politics and Religion, 9(3), 566–604. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048316000444

Whitehead, A. L., Perry, S. L., & Baker, J. O. (2018). Make America Christian again: Christian nationalism and voting for Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election. Sociology of Religion, 79(2), 147–171. https://doi.org/10.1093/socrel/srx070

Wilcox, C., Jelen, T. G., & Leege, D. C. (2016 [1993]). Religious group identifications: Toward a cognitive theory of religious mobilization. In Rediscovering the religious factor in American politics (pp. 72–99). Routledge.

Wolsko, C., Ariceaga, H., & Seiden, J. (2016). Red, white, and blue enough to be green: Effects of moral framing on climate change attitudes and conservation behaviors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 65, 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2016.02.005

Wong, J. S. (2018). Immigrants, evangelicals, and politics in an era of demographic change. Russell Sage Foundation.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lucas Borba for research assistance, as well as Ryan Strickler and the anonymous reviewers for helpful feedback. The authors also thank Geoff Layman, Christopher Karpowitz, and Jessica Preece for their suggestions and deftly handling the manuscript during the editorial transition.

Funding

The authors received no external funding for this research.

Open access funding provided by SCELC, Statewide California Electronic Library Consortium

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The authors affirm that this article adheres to the APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subject Research. The YouGov data collection received was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Vanderbilt University (#201317). The CES data collection received was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, Riverside (#HS 16–145). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare they have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

DeMora, S.L., Merolla, J.L., Newman, B. et al. Jesus was a Refugee: Religious Values Framing can Increase Support for Refugees Among White Evangelical Republicans. Polit Behav (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-024-09912-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-024-09912-2