Abstract

Do women have to work harder in office to be evaluated the same as men? When running for office, studies show that women are, on average, more qualified than men candidates. Once in office, women outperform their men colleagues in sponsoring legislation, securing funding, and in their constituency responsiveness. However, we do not know whether women need to outperform men in their political roles to receive equivalent evaluations. We report on a novel conjoint experiment where we present British voters with paired profiles describing Members of Parliament at the end of their first parliamentary term. Through manipulating the legislative outputs, gender, and party of MPs, we find that voters overall prefer politicians who are productive to politicians who are unproductive, and reward productive politicians in job performance and electability evaluations. However, we find no evidence that productive women are unjustly rewarded, nor do unproductive women face greater punishment than men. Our results suggest that, at least for productivity as measured in parliamentary-based activities, women politicians do not need to work harder than their men colleagues to satisfy voters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Do women have to work harder in office to be evaluated the same as men? While evidence of outright discrimination in voting preferences is now limited (Schwarz & Coppock, 2022), gender bias still operates in complex ways with respect to women’s recruitment to and retention in political office. This bias is mediated by a variety of factors including the level of office, partisanship, and candidate qualifications (Schneider & Bos, 2019). Less is known, however, about how gendered biases may operate once women reach elected office. Once in office, women have been shown to outperform their men colleagues in securing federal funding (Anzia & Berry, 2011), constituency responsiveness (Lazarus & Steigerwalt, 2018), and, at least in minority parties, are more successful at advancing their legislative initiatives (Volden & Wiseman, 2018; Volden et al., 2013). Women politicians also report that they feel pressured to work harder than men in office (Dittmar et al., 2018; Erikson & Verge, 2022).

At present, however, we do not know whether women need to outperform men in office to receive equivalent evaluations. In this paper, we assess whether the relationship between politicians’ productivity and voter approval is the same for men and women. Our design asks whether women politicians reap the rewards of their above average legislative efforts, or if they receive less credit than men. Recent evidence suggests that women’s above average efforts will only result in equal, rather than greater, voter approval compared to less productive men (Bauer, 2020). Establishing whether there is (gender) bias in voters’ judgements of politicians’ efforts in office has normative implications both for public perceptions of the “good” politician, and possibly women politicians’ career advancement and re-election prospects.

To test whether there is gender bias in how voters evaluate legislator productivity, we designed a conjoint experiment where we presented voters with paired profiles that describe the performance of Members of Parliament (MPs) at the end of their first parliamentary term. We manipulated: the performance and achievements of each MP on a diversity of parliamentary activities (sitting on parliamentary committees, speaking in debates, participating in votes, and constituency responsiveness), MP gender (man; woman), and MP party (Labour; Conservative). Through these manipulations, we assess whether there is gender bias in how voters evaluate the legislative efforts of politicians.

We report three main findings. First, encouragingly, we find clear evidence that voters reward politicians for their productivity in office. Politicians who are responsive to their constituents, actively campaign for issues, and participate in committees are preferred to those who do not. The magnitude of this effect, however, depends on the parliamentary activity: above all other legislative measures, voters value politicians dedicating their efforts to raising the concerns of the constituency. Second, these effects do not vary by politician gender. Voters do not prefer men who are active in constituency matters or who campaign actively on issues to women, nor do they punish women any more than men for not engaging in these activities. Third, contrary to our expectations, we find no evidence that productive women are unjustly rewarded, nor do unproductive women face greater punishment than their men colleagues with respect to both job evaluations and perceived electability. In short, politicians who work hard are rewarded, but this effect is not gendered.

While we find little evidence of gender bias in the forum we study, bias may persist in other forums. First, voters ultimately determine who gets elected to office, hence they are the focus of this paper, however another important audience for politicians’ efforts are their party leadership. Politicians rely on leadership within their own party for promotion to higher ranks. If party leaders unjustly reward or punish women politicians for their (un)productivity, women may be promoted to lower ranks or need to work harder to progress at the same rate as men. Recent work on Turkey supports this perspective, and finds that men who are active and engaged in legislative debates get promoted up the party ranks, but that this is not the case for women (Yildirim et al., 2021). Second, we present voters with neutrally framed descriptions of job performance. It may be the case that women have to work much harder in office for their performance to be communicated to voters in equal terms. If there is bias in how the work of men and women politicians is framed (Bauer & Taylor, 2022), or if men simply get more coverage overall (Smith, 2021), then this may in turn feed into how voters evaluate politicians. In short, in the forum we study—voter evaluations of neutral descriptions of politicians’ productivity efforts—we find no evidence of gender bias. However, the potential for bias in evaluations of women’s behaviour may emerge from many different forums.

Gender, Qualifications, and Voter Evaluations

Women are entering politics in increasing numbers, with the average percentage of women in national legislatures increasing from 10.1% to 26.4% between 1997 and 2022 (IPU, 2022). Despite this, there is limited systematic evidence on how gender bias operates when evaluating incumbent politicians. Once in office, there is some evidence women legislators perceive the need to work harder than their men counterparts (Dittmar et al., 2018; Erikson & Verge, 2022) and that this perception translates into higher productivity (Anzia & Berry, 2011; Lazarus & Steigerwalt, 2018). We ask whether women legislators need to work harder in office to be rated at similar levels to their men counterparts, and, conversely, if they face a greater punishment for being unproductive in office.

While the prevalence of overt bias against women politicians has become increasingly contested (Dolan, 2014), one form of the more nuanced ways we find that bias persists is the “qualification gap” recently summarised by Bauer (2020, p. 6): “Women win elections at equal rates to male candidates, but women win these elections by a narrower vote margin. And these women on average, have stronger qualifications relative to the victorious male candidates.”

Bauer (2020) describes this subtler form of bias where women must “run backwards in high heels”. The equality in electoral outcomes now documented conceals the fact that women may have to work harder to demonstrate their competency and achieve a level playing field in electoral outcomes. Observational research from the US and Europe has shown there is a gender gap in the qualifications men and women possess when running for office. On average, women have higher levels of qualifications, experience, and education than men (Fulton, 2012; Profeta & Woodhouse, 2022). Work on quotas in Italy and Sweden has found quota-women to be more qualified than non-quota men (O’Brien & Rickne, 2016; Weeks & Baldez, 2015). In the UK, the Labour Party’s quota-women have been shown to be more experienced than their men colleagues and the Conservative Party’s women MPs are more experienced overall than men Conservatives (Nugent & Krook, 2016). Focusing on the UK, Allen et al. (2016) also find that quota women candidates, compared to all other candidates, are equally qualified for political office and do not suffer with respect to promotion to higher office once entering the legislature.

The qualification gap therefore suggests that equal electoral outcomes are not the result of the elimination of bias, but rather that the women competing are more qualified than their men competitors. Observational studies have argued that similarity in success rates at the ballot box for men and women are attributable to this gap, for both incumbents and non-incumbents (Pearson & McGhee, 2013). For instance, Fulton and Dhima (2020) find that when men and women candidates have the same qualification standards, women are significantly less likely to get elected. When women are less or equally qualified than men, they face electoral barriers. However, when women are more qualified than men, they can escape historic gendered electoral penalties.

When running for office, women also perceive the need to be more qualified than men to be successful. Work at the candidate-level shows that women who anticipate sexism hold off on running for office until they reach a higher quality threshold, and instead develop more skills and resources before finally deciding to run (Fulton, 2012). Work on political ambition has shown that women often perceive themselves to lack the qualifications needed to serve in office (Lawless & Fox, 2012). This perception effects not only when they first decide to run (Fulton et al., 2006), but also, once in office, the decision to run for higher office (Maestas et al., 2006). This perceived qualification gap persists once entering office. Just as on the campaign trail, interview and survey data with women legislators finds that women feel they must work harder to prove their competency and reap the same rewards as men (Dittmar et al., 2018). In a survey of Swedish politicians, women report higher levels of pressure and anxiety in their roles than men (Erikson & Verge, 2022). As Puwar (2004) argues, women are “space invaders” in masculine legislative institutions and so face a “burden of doubt” from those who traditionally belong in the space to prove their competency and justify their presence.

This perception translates into action: on average, women have been found to be more productive legislators than men. Women outperform their men colleagues in securing federal funding (Anzia & Berry, 2011) and women in minority parties in the U.S. House of Representatives (Volden et al., 2013) and Senate (Volden & Wiseman, 2018) are more successful at advancing their legislative initiatives than men from minority parties. Although, other work finds no evidence that women mayors in the US are more effective than men with respect to policy-making efficacy (Ferreira & Gyourko, 2014). Women have also been shown to be more responsive to their constituents (Holman, 2015; Thomsen & Sanders, 2020) and travel back to their districts more often (Lazarus & Steigerwalt, 2018). In a recent field experiment, Butler et al. (2022) find that not only are women state legislators 10% more likely to be contacted by their constituents, but receive 14% more issue requests per constituent contact. Taken together, compared to men, women face a higher workload and may experience greater pressure in office.

Our design asks whether women need to outperform men in office to overcome gender biased evaluations and receive equivalent credit for the work they do. Do they reap the rewards of this above average performance? Or, conversely, are they punished more for not performing well? Given the evidence for the qualification gap in elections, we suggest that women must work harder than men to achieve level outcomes. Experimental evidence suggests that voter bias plays a role in this qualification gap, with women needing higher qualifications to overcome stereotyping. For instance, Bauer (2020) finds that voters create a higher bar for women candidates and incumbents. Further, the electorate needs to be reassured of women candidates’ quality more than they do their men competitors. Voters actively seek out more information on the competency of women candidates than men (Ditonto, 2017), and this information has a larger impact on evaluations of women candidates (Ditonto et al., 2014).

Our work makes two main contributions to the literature. First, at present, experimental work on the qualification gap and voter bias is limited to the US context, and we do not know whether these findings translate to other contexts. To the best of our knowledge, our paper is the first to examine the validity of these theories beyond the US. The UK provides a useful setting to compare these US-based findings to as it shares important similarities. Like the US, the UK has a majoritarian electoral system where voters elect individual candidates and not parties. There is a wealth of work that has shown that features of individual candidates are important for informing voter decision-making in single-member district electoral systems (see Gallagher & Mitchell, 2005). The UK system is becoming increasingly personalised: MPs actively manipulate their campaigning technique to focus on different elements—such as emphasising their party, personality, or constituency—depending on the political context (Pedersen & Van Heerde-Hudson, 2019). Studying the importance of voter preferences towards individual politicians might make less sense in many European parliamentary systems, where voters elect either parties or party lists and not individual candidates.

We believe that this is an important contribution, as it is necessary to consider whether findings on gender bias travel across political contexts. It is often assumed that gender stereotypes will travel across time and context, and yet gendered norms and stereotypes are dynamic concepts so we should be cautious of such assertions (Eagly et al., 2020). The UK has a different experience with gender politics: gender equality is a less polarising and party-political issue in the UK than in the US. Further, the UK has had three women national leaders, whereas the US has yet to elect any, and has a history of higher women’s parliamentary representation (IPU, 2022). The UK is therefore an appropriate place in which to test the cross-national robustness of these biases. Previous experimental work on the UK has found limited support for overt bias against women running for political office (Saha & Weeks, 2022). Yet, gender bias can operate in more complex ways. For instance, recent survey-based work finds that over half of the UK population harbours sexist beliefs and that the level of bias interacts with partisanship and Brexit attitudes (de Geus et al., 2022).

Secondly, we study the role of gender bias once politicians enter elected office. Previous work has shown that gendered voter evaluations vary by level and type of office: voters prefer men and stereotypically “masculine” traits for higher levels of executive office (Dolan, 2014; Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993b). Therefore, it might be the case that once women enter office, they do not face the same barriers that aspiring women do. Given the importance of the retention as well as the recruitment of women into politics, understanding how bias operates for incumbent women is vital. To date, much of the work on gender bias focuses on challenger or first-time candidates, and less is known about how gender bias operates once women enter office. We extend the study of gender bias in evaluations of the quality of politicians to incumbent UK politicians.

Hypotheses

We aim to identify whether women must work harder in office to overcome gender bias in voter attitudes. A wealth of work has identified gender bias in how voters perceive and evaluate women candidates (de Geus et al., 2022; Saha & Weeks, 2022) and a smaller body of work has shown bias towards incumbent politicians (Boussalis et al., 2021). Historically, studies have found that women are less likely to be selected as candidates for office (Norris & Lovenduski, 1995), and, upon running, were less likely to win than men (Fox & Oxley, 2003; Lawless, 2004). Experimental work on candidate choice has tended to present mixed results on the extent to which voters outright discriminate against women. Work on gender stereotyping in politics more broadly has emphasised that voters may not overall be biased towards women, but that this can depend on the political context or the type of voter (e.g., Anzia & Bernhard, 2022; Bauer & Taylor, 2022). In a recent meta-analytic study, Schwarz and Coppock (2022) re-analysed 67 studies on gender and candidate choice globally and report that women have a small electoral advantage relative to men, and that this effect is slightly more positive in recent studies. Despite this, other work measuring the degree to which voters harbour sexist attitudes in politics finds that more than half of the UK population hold sexist attitudes (de Geus et al., 2022).

While certain evidence increasingly suggests that outright bias against women candidates and politicians may now be limited (Schwarz & Coppock, 2022), and be present only in subtler and more nuanced forms (Bauer, 2020), other work suggests that anti-women sexist attitudes persist in the UK population (de Geus et al., 2022). Our design enables us to test for the subtler kind of bias that we describe above, in addition to whether voters in the UK harbour an outright preference for men over women. To test for outright bias, we investigate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1

Voters will prefer men MPs over women MPs.

Our primary quantity of interest lies in whether women must work harder than men to receive equality in evaluations. Indeed, if the women who run for office are of a higher quality than men, and women work harder than men once in office, then this suggests that women need to outperform men to achieve parity. We focus on how politicians’ efforts translate into two different forms of evaluations. First, perceptions of politicians’ job performance. We anticipate that voters will perceive differently the work that women dedicate to their roles in office compared to how they perceive men. Politicians are expected to be competent, and to be able to carry out their jobs to a high standard. Gender roles consistent with stereotypically “feminine” behaviours suggest that while women are expected to be kind, compassionate, caring, and communal, “masculine” behavioural norms are instead associated with being assertive, confident, and independent (Eagly & Karau, 2002). As such, because men are both the traditional occupants of political office, and the congruence between masculine behavioural stereotypes and leadership behavioural stereotypes (Koenig et al., 2011), men’s competence in office is often assumed in a way that women’s is not.

While stereotypes around competence in office have equalised somewhat over time (Donnelly et al., 2016), women have historically been perceived as less competent (Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993a) and voters seek out more information about the qualifications of women than men (Ditonto et al., 2014). Because of men’s assumed competence, voters might perceive a poor performing man as more highly achieving than a poor performing woman. Recent work by de Geus et al. (2021) investigated the attribution of credit and blame in poor and positive governing performance of men and women executives in the US and Australia, finding that gendered bias in performance evaluations is less pronounced in voter evaluations of politicians who carry out their work to a high standard, however more pronounced in evaluations of poor performing politicians. We therefore expect to see more evidence of gender bias in voter evaluations of poor performing MPs, however as performance increases, we expect that voters’ evaluations of politicians’ job performance will equalise. This leads us to our second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2

Women MPs will require a higher objective job performance level to receive similar job performance evaluations as men MPs.

Second, we ask voters to evaluate the likelihood that an MP would be re-elected. As discussed above, women politicians need to work harder than their men colleagues to overcome biased perceptions of their abilities including electability. We expect that the relationship between objective performance and perceived electability will not be equal for men and women, rather we expect that women will have to work harder and achieve more to reap the same rewards. Recent work has shown that anti-women bias can occur when voters anticipate that others will be biased towards women (Bateson, 2020). We anticipate that voters will rate poor performing women as particularly unelectable both because they themselves harbour biases towards women and because they likely will anticipate that other voters will not support poor performing women as opposed to poor performing men. This leads us to our final hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3

Women MPs will require a higher objective job performance level to be rated as similarly electable as men MPs.

Experimental Design

To test our expectations, we designed a “forced choice” conjoint experiment (Hainmueller et al., 2014) where we presented respondents with descriptions of two fictitious MPs at the end of their first parliamentary term. An experimental approach allows us to isolate the causal effect of MP gender on voter evaluations of MP productivity. Experimental methods are common in studies on gender-based stereotyping (Campbell et al., 2019a) and legislative effectiveness more broadly (Butler et al., 2021; Fleming, 2021).

An alternative observational approach linking MP-productivity to vote share would struggle to account for many sources of confounding—such as MP-specific characteristics or factors specific to the local context—which influence MPs’ legislative activities or their publicising of these activities during campaigns (Mayhew, 1974; Pedersen & VanHeerde-Hudson, 2019). We task voters with comparing two incumbent MPs and providing ratings of the MPs’ electability and job performance. Although not a direct simulation of real-world electoral processes, the forced choice compels respondents to think more carefully about trade-offs and is a tool used in similar conjoint survey designs in the UK context (Campbell et al., 2019a). While experiments have drawbacks on external validity, they offer better internal validity. Conjoint designs present voters with various attributes at once and are therefore thought to help increase the external validity of experimental designs by better mimicking the information voters receive in real-world elections (Hainmueller et al., 2014).

Our experimental design was fielded by YouGov to their Great Britain online panel between June 22nd and 25th, 2021. We pre-registered our design, hypotheses, and analysis plan (Hargrave & Smith, 2021). The sample was 1624 people who are nationally representative of the British public on a range of attitudinal and demographic criteria. We tasked respondents with reading short texts that described the performance of two MPs at the end of their first parliamentary term. We manipulated the descriptions of the politicians on three dimensions. First, MP gender (man; woman). Second, MP party (Labour; Conservative). Third, the productivity of the MP in office on a range of key aspects of politicians’ roles: sitting on parliamentary committees, speaking in debates, participating in votes, and representing constituents. Table 1 summarises the attributes and their levels.

There is a rich body of literature that has shown that active and engaged parliamentary work can positively influence MPs’ career prospects (Baumann et al., 2017), and that there may be gendered implications of this (Yildirim et al., 2021). We select each of our productivity measures as they are commonly identified as the key legislative activities that UK MPs engage in (Proksch & Slapin, 2012). Those more familiar with US politics may wonder why we have chosen not to include a measure of whether politicians successfully secure federal funding. While in the US legislators dedicate significant time to securing “pork barrel” spending in their districts (Anzia & Berry, 2011), for external validity concerns this would not be an appropriate measure of politician productivity in the UK as individual legislators have little influence on budget allocations.

While we are interested in identifying whether there are gender differences in evaluations of MP productivity overall, certain attributes of productivity may introduce greater bias into voters’ evaluations than others. Previous UK experimental work has shown that constituency service is a commodity that is highly valued by voters (Campbell et al., 2019a, 2019b). Further, dealing with the concerns of the constituency may more closely relate to feminine stereotypes of women’s supposed “communality” than our other attributes (Eagly & Karau, 2002; Hargrave & Blumenau, 2022). At least anecdotally too, women politicians are thought to engage in constituency activities to a greater extent than men (Childs, 2004). Therefore, it may be the case that voters will punish women who are unproductive in their constituency service. The analysis we carry out below allows us to assess whether there is gender bias in both evaluations of the aggregated productivity measures but also for each of our productivity measures individually.

Following an introduction screen describing the task, respondents were presented with two profiles describing fictional MPs. We asked each respondent three questions: (1) which candidate they would rather have as their MP, (2) their perceptions of each MP’s job performance, and (3) their perceptions of each MP’s re-election chance. An example of the forced choice profiles can be seen in Fig. 1.

For each MP profile, all attributes were randomly assigned, with no restrictions on attribute combination except MP first name and surname. The order in which the attributes appeared was randomly assigned across respondents but fixed for each respondent across MP profiles to ensure ease of comparison. We ask each respondent to complete the task only once, which provides us with 1624 forced choice responses and 3248 MP-level ratings.

Methodology

Outcome and Explanatory Variables

We have three outcomes. First, a respondent’s decision in the forced choice on their MP preference (binary: not selected; selected). Second, the MP’s job performance, which ranges from 0 to 7 and includes a “don’t know” option, where 0 represents strong disapproval and 7 strong approval. Third, the MP’s electability, which also ranges from 0 to 7 and includes a “don’t know” option, where 0 represents extremely unlikely to be re-elected and 7 extremely likely. We drop all “don’t know” responses in the analysis described below.

We have seven explanatory variables. First, the MP’s committee membership (binary: does not sit on committees; sits on committees). Second, the MP’s issue campaigning abilities (binary: unsuccessfully campaigns; successfully campaigns). Third, the MP’s voting and legislation activities (binary: less productive; more productive). Fourth, the MP’s constituency responsiveness (binary: rarely responsive; often responsive). Fifth, in addition to the individual treatment effects of each of the attributes of MP-quality, we construct a continuous scale of each MP’s objective performance in their role. To construct the scale, we assign a 1 for every positive attribute that an MP is assigned (sits on committees, successfully campaigns, more productive, and often responsive) and a 0 for every negative attribute that an MP is assigned (does not sit on committees, unsuccessfully campaigns, less productive, and rarely responsive), and aggregate the scores for each MP. This ranges for 0 to 4, where 0 is the worst performing and 4 is the best performing MP. Sixth, the MP gender (binary: man; woman). Seventh, the MP party (binary: Labour; Conservative).

Empirical Strategy

Following Hainmueller et al. (2014), we estimate the probability that a respondent chooses an MP via:

where i indicates the respondent and j indicates the scenario. For us, i ∈ {1,2,….,1624} and j ∈ {1,2}. Each respondent i yields 2 observations: 1 round, and 2 choices per round. The unit of analysis is the hypothetical MP profile (N = 3248), the outcome is a binary indicator for whether the respondent prefers the MP or not, and the explanatory variables are the attributes of the MP. Further, we can also test H1 with our other two outcomes—Electability and Job Performance. To do so, we estimate two OLS models for our outcomes Yi(j) for an individual i in a scenario j of the following form:

where our primary quantity of interest is β1 which tells us, holding constant party and performance measures, whether voters rate the electability or job performance of men and women differently. As there are multiple observations per respondent, we cluster standard errors at the respondent level i.

Next, we are interested in whether women must work harder than men to receive equivalent evaluations. To do so, we estimate two sets of analysis. First, we estimate OLS models for our analysis for all three of our outcomes—MPPreference, Electability, and JobPerformance—Yi(j) for an individual i in a scenario j of the following form:

where β1 describes the difference in preference for an MP, electability, and job performance evaluations between men and women MPs who do not sit on committees, are unsuccessful at campaigns, less productive than the average MP at attending votes and proposing changes to legislation, and who are unresponsive to their constituents. β2–β5 describe the effect of each of our positive performance attributes to the control condition α. Our primary quantities of interest are β6–β9, which describe the difference in the effect of performing well on each of the performance measures for men and women MPs. We cluster standard errors at the respondent level i.

Second, to assess whether women must reach higher performance levels in order to achieve equivalent evaluations with men, we estimate a series of OLS models for our three outcomes—MP Preference, Electability, and Job Performance—Yi(j) for an individual i in a scenario j of the following form:

where β1 describes the difference in evaluations of job performance, electability, and preference for an MP between unproductive men and women MPs. β2 describes the effect of increased productivity among men MPs. β3 describes the difference in the effect of increased productivity for men and women MPs. Again, we cluster standard errors in all models at the respondent-level i.

Results

Unconditional Effects

Figure 2 shows the result from the model described in Eq. 1.Footnote 1 There are three findings to note. First, voters overall clearly prefer productive politicians to unproductive politicians. Respondents are significantly more likely to choose MPs that are more productive across the four activities—constituency responsiveness, committee membership, issue campaigning, and voting and legislation. The magnitude of these effects varies across the type of activity. An MP being responsive to constituency demands has the largest impact on the likelihood respondents prefer the MP, with sitting on committees having the smallest effect. That active constituency responsiveness yielded the largest effect supports previous observational (Blumenau & Damiani, 2021) and experimental (Campbell et al., 2019a) work that has found UK voters highly value these efforts, that politicians are sensitive to this and dedicate significant effort to these activities.Footnote 2

Second, Fig. 2 also tests for overt gender bias in line with H1. We see no evidence in support of H1: there is no statistically significant difference in voter preferences for men or women MPs. This finding mirrors other recent work that has found little evidence of outright gender bias in voter preferences, and indeed the direction of the point estimate at least supports work by Schwarz and Coppock (2022) which has shown that voters now actually afford women a slight electoral reward compared to men.

Next, Fig. 3 shows the results from the model described in Eq. 2, and allows us to assess whether our productivity measures, MP gender, and MP party also affect electability and job performance evaluations. The left panel shows the results for electability. The results largely reinforce the figure above: voters rate more productive MPs as more electable, however there is no evidence of direct gender bias. The right panel shows the results for job performance. Again, voters reward productive MPs in performance evaluations, however here we see a significant positive effect for women MPs. The figure suggests that, although only a substantively small effect, voters rate women as higher on job performance than men. Taken together, this analysis shows no support for H1. All else equal, voters do not prefer men over women and, if anything, voters evaluate women higher for their job performance.

Conditional Effects by MP Gender

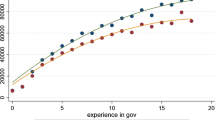

Our primary quantity of interest lies in whether women need to work harder than men to receive equivalent evaluations. We assess this in several ways. First, we identify whether the effect of each of our parliamentary productivity attributes on electability evaluations, job performance evaluations, and the preference for an MP differ depending on MP gender. In particular, whether certain productivity attributes introduce gender bias into voters’ evaluations to a greater extent than others. To assess this, in Fig. 4, we implement the model described in Eq. 3. The left panel (electability), middle panel (job performance), and right panel (MP preference), each tell a consistent story: politicians who perform well on each of our measures are rewarded compared to those who do not, but this effect is not different for men and women. Therefore, despite constituency service being more closely related to ideas of feminine “communal” stereotypes (Eagly & Karau, 2002), it is not the case that voters particularly punish women who are unresponsive to their constituents.

Second, we turn to the analysis that concerns our continuous measure of objective performance. Recall, the worst performing MP score a 0 and the best a 4. We present the predicted relationship between objective performance, electability evaluations, job performance evaluations, and preference for an MP in Fig. 5. There are several findings to note. First, the productivity manipulations work as expected: for both men and women, voters rate electability, job performance, and preference for an MP as higher when the MP is objectively more productive. When politicians work harder, voters respond positively, and reward them for it. This finding also complements previous experimental work on the UK that finds that voters view hard working MPs more positively (Fleming, 2021), and in the US which shows that presenting constituents with information about their representatives’ law-making effectiveness increases voters’ approval, even accounting for partisanship (Butler et al., 2021). Second, we see no evidence of the subtler kind of bias that we described in H2 and H3. In all three panels, the relationship between voters’ evaluations of politicians and objective performance follows an almost identical trajectory for men and women, and at no point is there a statistically significant difference. Taken together, we see no evidence of the subtler bias described above.

Overall, contrary to our expectations, we find no evidence of gender bias in voter evaluations of politicians’ productivity in office. There is no significant difference in voter evaluations of high or low performing MPs’ job performance, electability, or preferences for men and women, and voters harbour no outright preference for men over women.

Robustness Check: Party Preference Bias

We might be concerned that this “null” effect is the result of presenting voters with information about MPs that is framed in a neutral manner with a clear signal about their objective job performance. Voters may simply always evaluate productive MPs higher on job performance and electability regardless of any bias they hold. Here, we test for the presence of any bias by examining the likely bias of party preference. Past work has shown that voters’ partisanship can affect how they interpret political facts (Druckman et al., 2013) and influence the degree to which they positively evaluate politicians’ efforts (Fleming, 2021). Although other recent work has shown that co-partisans in the US are willing to punish ineffective representatives, and reward effective representatives from other parties (Butler et al., 2021). Our expectation is that voters will, first, rate an MP from their own party as higher on each of our outcomes, second, be less critical of poor performance in office, and third, be more rewarding of good performance.

To examine the presence of party preference bias, we leverage YouGov’s information on respondent lagged vote from the 2019 General Election and coded a variable that takes the value of 1 if the respondent and MP are from the same party, and 0 if they are not. In Fig. 6, we present the interaction between objective performance and our outcomes for party-(in)congruent respondents. In the appendix, we report the full results, in addition to the bivariate relationships between party congruence and evaluations. Given that interpreting only coefficients for interaction effects can be misleading (Brambor et al., 2017, p. 71), we focus on interpreting the slopes in Fig. 6. Here we see some evidence of party preference bias. In the left panel, which describes the relationship between electability and performance for party-congruent (blue solid lines) and party-incongruent (grey dashed lines) voters, we see that there is a significant difference for poor performing MPs. Party-congruent voters rate a poor performing MP as more electable than a poor performing MP from a different party. Turning to the middle panel, which shows the equivalent analysis for job performance evaluations, we see very marginal differences between party-(in)congruent voters. There is a significant difference as performance increases, as party congruent MPs are rated higher on job performance, but these differences are small. Finally, turning to the right panel, which presents the results for MP preference, we see clear bias in that party congruent voters are consistently more likely to choose the party congruent MP and the likelihood of this increases with objective performance.

Therefore, while we see no evidence that gender bias influences voter evaluations of productive and unproductive MPs, it is not the case that no bias is present. We find evidence of party preference bias and can therefore be more confident that presenting voters with neutrally framed descriptions of MPs’ job performance does not rule out the potential for any kind of bias in evaluations.

Conclusion

Once in office, women have been shown to both perceive the need to work harder and actually work harder than their men colleagues to prove themselves as legislators. In this paper, we asked whether women need to work harder than men to be afforded equivalent reward by voters, and, conversely, if they face a greater punishment for unproductivity. To test these questions, we designed a conjoint experiment where we presented UK voters with descriptions of MPs at the end of their first parliamentary term. We varied MP gender, party, and productivity on a range of parliamentary activities. Our results show no overt gender bias in voters’ preferences for men over women MPs. Further, unproductive men do not receive more positive evaluations than unproductive women, nor are productive men rewarded for their efforts any more than productive women. Overall, women do not need to work harder than men once in office to overcome gender bias from voters.

There are several possible explanations for these “null” results. First, while observational evidence on women’s higher qualifications and productivity is focused on both the US and Europe, experimental work has so far focused exclusively on the US. We are the first to assess whether this bias exists in the UK and find little evidence that it does. We are not the first UK-based experimental study that has found that the same biases observed in the US do not necessarily travel to the UK. Indeed, several other recent studies on stereotyping and bias have also uncovered null effects (Campbell et al., 2019a; Hargrave, 2022; Saha & Weeks, 2022). One explanation might be that the UK has historically had more experience with women elected to office than in the US. Not only has the UK had three women leaders, but women’s legislative representation has also tended to be higher (IPU, 2022). It may therefore be the case that British voters’ greater familiarity with women legislators and leaders has led to less biased attitudes towards women politicians than in the US. To test this, we encourage scholars to conduct similar experiments in other contexts, such as Western European democracies with a history of women’s leadership and where voters elect individual candidates.

Second, differences in political systems may also impact voter biases across contexts. Given we have compelling evidence that different political systems and institutions, such as proportional representation, impact the descriptive representation of women (Matland & Studlar, 1996), we should take seriously how these systematic differences interact with voter bias towards women politicians. For instance, more party-led, centralised candidate nomination processes, such as those in the UK, may offer different signals of quality than the more voter led process in the US (Norris & Lovenduski, 1995). A fruitful avenue for further research is to continue to test these biases in comparative contexts. For instance, by applying methods such as list experiments (Burden et al., 2017) or survey measures of sexism (de Geus et al., 2022), to further work on the relationship between political context and gendered biases.

Third, while the forced-choice component of our design allows us to directly test and compare performance in office, we acknowledge that comparing two incumbent MPs differs from how constituents make decisions in real-world UK elections. Unlike electoral contexts where voters select between an incumbent and a challenger, it is possible that in our design, incumbency was a sufficient signal of quality to overshadow any concerns about women’s qualifications. The evidence on incumbency effects is mixed, Dolan (2014) finds incumbency can overcome gender stereotypes, while Bauer (2020) and Fulton (2012) find this may be mediated by the qualification gap. Future work could test how high or low legislative performance may stand up to different challengers. For instance, a lower level of qualification may be needed for men challengers to be rated equally to productive women incumbents.

Fourth, while we find that women politicians may not need to work harder in their roles than their men colleagues, it is possible that these dynamics may operate very differently for women in professional contexts. A history of surveys into working professionals have revealed that women report finding their jobs to be more demanding than men and perceive the need to work harder than men,Footnote 3 and that these perceptions of a need to work harder is in part due to stricter performance standards being imposed on women (Gorman & Kmec, 2007; Kmec & Gorman, 2010). While politicians likely do internalise expectations based on their own gender, including the expectation of potential voter penalties, these expectations are likely to be at least partially eclipsed by their roles as political elites (Schneider & Bos, 2014). Therefore, by focusing our attention on elite women, it is possible that our findings may understate the extent to which non-elite women may be subject to pressures to work harder than men. Future work might use experimental designs to examine how the perceived bias that women must work harder, or face punishments may vary across different contexts, both political and professional.

Finally, voter evaluations are not the only way bias towards women’s behaviour in office may manifest. Voters are one important audience for politicians’ legislative efforts as they ultimately determine who gets into office. However, MPs are also reliant on their party leadership and colleagues to recognise and reward their efforts. It may be the case that women legislators’ peers and leaders unjustly reward or punish their efforts, and that women either do not get promoted to senior positions, or get promoted at slower rates, than men. Recent work in Turkey supports this theory, finding that men who are active and engaged in legislative debates get promoted up the party ranks, but this is not the case for women (Yildirim et al., 2021). Work on quota-women in Italy similarly finds that, once quota rules are removed, party leaders caused women to be re-elected at lower rates (Weeks & Baldez, 2015). A fruitful avenue for further study would be to understand how bias may operate among elite audiences of women’s legislative efforts.

Women legislators perceive the need to work harder in office (Dittmar et al., 2018) and this translates into their greater productivity in their constituency and legislative work (Anzia & Berry, 2011; Thomsen & Sanders, 2020). Our results suggest that we can be cautiously optimistic that, at least in the UK, women politicians do not appear to need to go over and above in their jobs to reap the same rewards as men. Voters in the UK reward politicians who are productive regardless of their gender, and, as such, women politicians perhaps do not need to take on an extra “burden of doubt” (Puwar, 2004) to satisfy voters.

Data Availability

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/7BVBUW

Notes

In the appendix, we assess how treatment effects may be sensitive to the gender pairing of the profiles that respondents receive. When examining only respondents who were presented with one woman MP and one man MP, we uncover a positive and statistically significant, although substantively very small, preference for a woman compared to a man. For the analysis where we interact gender with objective performance, we find no evidence that the results are sensitive to profile gender pairing.

See, for example, numerous UK Employer Skills Surveys.

References

Allen, P., Cutts, D., & Campbell, R. (2016). Measuring the quality of politicians elected by gender quotas: Are they any different? Political Studies, 64(1), 143–163.

Anzia, S. F., & Bernhard, R. (2022). Gender stereotyping and the electoral success of women candidates: New evidence from local elections in the United States. British Journal of Political Science, 52, 1–20.

Anzia, S. F., & Berry, C. R. (2011). The Jackie (and Jill) Robinson effect: Why do congresswomen outperform congressmen? American Journal of Political Science, 55(3), 478–493.

Bateson, R. (2020). Strategic discrimination. Perspectives on Politics, 18(4), 1068–1087.

Bauer, N. M. (2020). The qualifications gap: Why women must be better than men to win political office. Cambridge University Press.

Bauer, N. M., & Tatum, T. (2022). Selling them short? Differences in news coverage of female and male candidate qualifications. Political Research Quarterly, 2022, 1–15.

Baumann, M., Debus, M., & Klingelhöfer, T. (2017). Keeping one’s seat: The competitiveness of MP renomination in mixed-member electoral systems. The Journal of Politics, 79(3), 979–994.

Blumenau, J., & Damiani, R. (2021). The (increasing) discretion of MPs in parliamentary debate. In H. Bäck, M. Debus, & J. M. Fernandes (Eds.), The politics of legislative debate (pp. 775–800). Oxford University Press.

Boussalis, C., Coan, T. G., Holman, M. R., & Müller, S. (2021). Gender, candidate emotional expression, and voter reactions during televised debates. American Political Science Review, 115(4), 1242–1257.

Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., & Golder, M. (2017). Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, 14(1), 63–82.

Burden, B. C., Ono, Y., & Yamada, M. (2017). Reassessing public support for a female president. Journal of Politics, 79(3), 1073–1078.

Butler, D. M., Hughes, A. G., Volden, C., & Wiseman, A. E. (2021). Do constituents know (or care) about the lawmaking effectiveness of their representatives? Political Science Research and Methods, 2021, 1–10.

Butler, D. M., Naurin, El., & Öhberg, P. (2022). Constituents ask female legislators to do more. The Journal of Politics, 2022, 1–15.

Campbell, R., Cowley, P., Vivyan, N., & Wagner, M. (2019a). Legislator dissent as a aalence signal. British Journal of Political Science, 49(1), 105–128.

Campbell, R., Cowley, P., Vivyan, N., & Wagner, M. (2019b). Why friends and neighbors? Explaining the electoral appeal of local roots. Journal of Politics, 81(3), 937–951.

Childs, S. (2004). New labour’s women MPs: Women representing women. Routledge.

de Geus, R. A., McAndrews, J. R., Loewen, P. J., & Martin, A. (2021). Do voters judge the performance of female and male politicians differently? Experimental evidence from the United States and Australia. Political Research Quarterly, 74(2), 302–316.

de Geus, R., Ralph-Morrow, E., & Shorrocks, R. (2022). Understanding ambivalent sexism and its relationship with electoral choice in Britain. British Journal of Political Science, 2022, 1–20.

Ditonto, T. (2017). A high bar or a double standard? Gender, competence, and information in political campaigns. Political Behavior, 39, 301–325.

Ditonto, T. M., Hamilton, A. J., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2014). Gender stereotypes, information search, and voting behavior in political campaigns. Political Behavior, 36(2), 335–358.

Dittmar, K., Sanbonmatsu, K., & Carroll, S. J. (2018). A seat at the table: Congresswomen’s perspectives on why their presence matters. Oxford University Press.

Dolan, K. (2014). Gender stereotypes, candidate evaluations, and voting for women candidates: What really matters? Political Research Quarterly, 67(1), 96–107.

Donnelly, K., Twenge, J. M., Clark, M. A., Shaikh, S. K., Beiler-May, A., & Carter, N. T. (2016). Attitudes toward women’s work and family roles in the United States, 1976–2013. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(1), 41–54.

Druckman, J. N., Peterson, E., & Slothuus, R. (2013). How elite partisan polarization affects public opinion formation. American Political Science Review, 107(1), 57–79.

Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573–598.

Eagly, A. H., Nater, C., Miller, D. I., Kaufmann, M., & Sczesny, S. (2020). Gender stereotypes have changed: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of U.S. public opinion polls from 1946 to 2018. American Psychologist, 75(3), 301–315.

Erikson, J., & Verge, T. (2022). Gender, power and privilege in the parliamentary workplace. Parliamentary Affairs, 75(1), 1–19.

Ferreira, F., & Gyourko, J. (2014). Does gender matter for political leadership? The case of U.S. mayors. Journal of Public Economics, 112, 24–39.

Fleming, T. G. (2021). Partisanship and the effectiveness of personal vote seeking. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 2021, 1–34.

Fox, R. L., & Oxley, Z. M. (2003). Gender stereotyping state executive elections: Candidate selection and success. Journal of Politics, 65(3), 833–850.

Fulton, S. A. (2012). Running backwards and in high heels: The gendered quality gap and incumbent electoral success. Political Research Quarterly, 65(2), 303–314.

Fulton, S. A., & Dhima, K. (2020). The gendered politics of congressional elections. Political Behavior, 2020, 1–27.

Fulton, S. A., Maestas, C. D., Maisel, S. L., & Stone, W. J. (2006). The sense of a woman: Gender, ambition, and the decision to run for congress. Political Research Quarterly, 59(2), 235–248.

Gallagher, M., & Mitchell, P. (2005). The politics of electoral systems. Oxford University Press.

Gorman, E. H., & Kmec, J. A. (2007). We (have to) try harder: Gender and required work effort in Britain and the United States. Gender and Society, 21(6), 828–856.

Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D. J., & Yamamoto, T. (2014). Causal inference in conjoint analysis: Understanding multidimensional choices via stated preference experiments. Political Analysis, 22(1), 1–30.

Hargrave, L. (2022). A double standard? Gender bias in voters’ perceptions of political arguments. British Journal of Political Science. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123422000515

Hargrave, L., & Blumenau, J. (2022). No longer conforming to stereotypes? Gender, political style, and parliamentary debate in the UK. British Journal of Political Science, 52(4), 1584–1601.

Hargrave, L., Smith, J. C. (2021). Working hard or hardly working? Gender and voter evaluations of legislator productivity. EGAP (ID: 202106515AA). Retrieved from https://osf.io/n62ek

Holman, M. R. (2015). Women in politics in the American city. Temple University Press.

Huddy, L., & Terkildsen, N. (1993a). Gender stereotypes and the perception of male and female candidates. American Journal of Political Science, 37(1), 119–147.

Huddy, L., & Terkildsen, N. (1993b). The consequences of gender stereotypes for women candidates at different levels and types of office. Political Research Quarterly, 46(3), 503.

IPU. (2022). Women in National Parliaments. Retrieved from http://archive.ipu.org/wmn-e/world.htm

Kmec, J. A., & Gorman, E. H. (2010). Gender and discretionary work effort: Evidence from the United States and Britain. Work and Occupations, 37(1), 3–36.

Koenig, A. M., Eagly, A. H., Mitchell, A. A., & Ristikari, T. (2011). Are leader stereotypes masculine? A meta-analysis of three research paradigms. Psychological Bulletin, 137(4), 616–642.

Lawless, J. L. (2004). Women, war, and einning elections: Gender stereotyping in the post-september 11th era. Political Research Quarterly, 57(3), 479–490.

Lawless, J. L., & Fox, R. L. (2012). Men rule: The continued underrepresentation of women in US politics. Women & Politics Institute.

Lazarus, J., & Steigerwalt, A. (2018). Gendered vulnerability: How women work harder to stay in office. University of Michigan Press.

Maestas, C. D., Sarah Fulton, L., Maisel, S., & Stone, W. J. (2006). When to risk it? Institutions, ambitions, and the decision to run for the U.S. House. American Political Science Review, 100(2), 195–208.

Matland, R. E., & Studlar, D. T. (1996). The contagion of women candidates in single-member district and proportional representation electoral systems: Canada and Norway. The Journal of Politics, 58(3), 707–733.

Mayhew, D. R. (1974). Congress: The electoral connection. Yale University Press.

Norris, P., & Lovenduski, J. (1995). Political recruitment: Gender, race and class in the British Parliament. Cambridge University Press.

Nugent, M. K., & Krook, M. L. (2016). All-women shortlists: Myths and realities. Parliamentary Affairs, 69, 115–135.

O’Brien, D. Z., & Rickne, J. (2016). Gender quotas and women’s political leadership. American Political Science Review, 110(1), 112–126.

Pearson, K., & McGhee, E. (2013). What it takes to win: Questioning “Gender Neutral” outcomes in U.S. House Elections. Politics & Gender, 9(4), 439–462.

Pedersen, H. H., & VanHeerde-Hudson, J. (2019). Two strategies for building a personal vote: Personalized representation in the UK and Denmark. Electoral Studies, 59, 17–26.

Profeta, P., & Woodhouse, E. F. (2022). Electoral rules, women’s representation and the qualification of politicians. Comparative Political Studies, 2022, 1–30.

Proksch, S. O., & Slapin, J. B. (2012). Institutional foundations of legislative speech. American Journal of Political Science, 56(3), 520–537.

Puwar, N. (2004). Space invaders: Race, gender and bodies out of place. Berg.

Saha, S., & Weeks, A. C. (2022). Ambitious women: Gender and voter perceptions of candidate ambition. Political Behavior, 44, 779–805.

Schneider, M. C., & Bos, A. L. (2014). Measuring stereotypes of female politicians. Political Psychology, 35(2), 245–266.

Schneider, M. C., & Bos, A. L. (2019). The application of social role theory to the study of gender in politics. Political Psychology, 40(1), 173–213.

Schwarz, S., & Coppock, A. (2022). What have we learned about gender from candidate choice experiments? A meta-analysis of sixty-seven factorial survey experiments. Journal of Politics, 84(2), 655–668.

Smith, J. C. (2021). Masculinity and femininity in media representations of party leadership candidates: Men “Play the Gender Card” too. British Politics, 17, 1–22.

Thomsen, D. M., & Sanders, B. K. (2020). Gender differences in legislator responsiveness. Perspectives on Politics, 18(4), 1017–1030.

Volden, C., & Wiseman, A. E. (2018). Legislative effectiveness in the United States senate. Journal of Politics, 80(2), 731–735.

Volden, C., Wiseman, A. E., & Wittmer, D. E. (2013). When are women more effective lawmakers than men? American Journal of Political Science, 57(2), 326–341.

Weeks, A. C., & Baldez, L. (2015). Quotas and qualifications: The impact of gender quota laws on the qualifications of legislators in the Italian Parliament. European Political Science Review, 7(1), 119–144.

Yildirim, T. M., Kocapınar, G., & Ecevit, Y. A. (2021). Status incongruity and backlash against female legislators: How legislative speechmaking benefits men, but harms women. Political Research Quarterly, 74(1), 35–45.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jack Blumenau, Daniel Devine, and attendees at working group seminars at University College London and the PSA Elections, Public Opinion and Parties Conference 2021 for their thoughtful feedback. We also thank Patrick English at YouGov for implementing the survey design. We are very grateful to the PSA Elections, Public Opinion and Parties specialist group for funding this experiment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hargrave, L., Smith, J.C. Working Hard or Hardly Working? Gender and Voter Evaluations of Legislator Productivity. Polit Behav 46, 909–930 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09853-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09853-8