Abstract

People of color (PoC) will soon become a demographic majority in the U.S., but this overlooks major differences in how various PoC are treated by American society and the political priorities they hold. We build a theory that explains when and why some PoC express more unified political views. Despite variation in their social positions, people of color share common sources of marginalization. For example, although Asian Americans are stereotyped as a model minority and Latinos as low-status, both are deemed perpetual foreigners. We claim that shared marginalization sparks solidarity between PoC, which strengthens their support for policies that do not implicate their ingroup, thus forging interminority unity. Using survey data, Study 1 (N = 2400) shows that Asian adults report weaker solidarity with PoC than do Latinos, plus less support for policies that accommodate unauthorized immigrants, which implicate Latinos. Studies 2 and 3 randomly assign Asian (N = 641) and Latino (N = 624) adults to read about a racial outgroup marginalized as foreign (vs. control article). This heightens solidarity with PoC, which then boosts Asian support for flexible policies toward undocumented immigrants (which implicate Latinos) and Latino support for generous policies toward high-skill immigrants (which implicate Asians). We discuss how our results clarify the opportunities and limits of political unity among PoC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The U.S. has confronted each racially defined minority with a unique form of despotism and degradation…Mexicans were invaded and colonized… Asians faced exclusion.

-Omi and Winant (1986, p. 1)

Solidarity may be easier to achieve between groups that…have similar resulting experiences with prejudice…

-Zou and Cheryan (2017, p. 698)

As America’s demographics continue to churn, people of color (PoC) are soon poised to become a majority of the U.S. population (Pérez, 2021a). This news has been heralded for decades now (e.g., Rodríguez-Muñiz, 2021), with some cities—such as Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, and Phoenix—already populated by large combinations of African Americans, Asian Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, and other minoritized groups (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). Yet despite this steady rise in people of color, another important fact is often overlooked. Although in the aggregate, PoC are an impressive demographic force, in politics, their mobilization toward shared goals is often underwhelming, with tensions, conflicts, and violence regularly breaking out between some minoritized communities (Benjamin, 2017; McClain & Karnig, 1990; McClain et al., 2007; Wilkinson, 2015). Alas, enduring differences exist between non-Whites in terms of their arrival to the U.S., their treatment by U.S. authorities, and their political aspirations and goals (Kim, 2000; Masuoka & Junn, 2013; Pérez, 2021b; Zou & Cheryan, 2017). Under what conditions, then, will distinct minoritized groups in the U.S. unify politically as people of color?

Further clarity on this question is hindered by a trio of conceptual, theoretical, and methodological hurdles. In terms of conceptualization, prior work generally traces the lack of solidarity between people of color to deep-seated prejudices and stereotypes that minoritized individuals possess about each other, with some of these racialized beliefs exacerbated by scarcity in material goods (e.g., Benjamin, 2017; Carey et al., 2016; McClain & Karnig, 1990; McClain et al., 2007; Wilkinson, 2015). This approach, correctly, trains our attention on the immense difficulties that hinder greater cooperation between people of color. Yet it is also less clear on the range of psychological opportunities that exist between minoritized communities to close ranks for common political purposes (e.g., Merseth, 2018; Sirin et al., 2017, 2021).

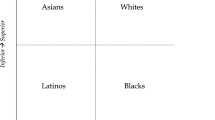

Some of these opportunities come into sharper relief if we consider the social positions of communities of color. As several social scientists teach us (e.g., Bobo & Hutchings, 1996; Kim, 2000; Masuoka & Junn, 2013; Zou & Cheryan, 2017), America’s racial and ethnic minorities are arrayed in a descending hierarchy of power and prestige, with Whites perched atop and people of color stationed below. Recent work has further innovated this perspective by illuminating richer variation in the subordinated stations of minoritized communities (e.g., Pérez, 2021a). As Zou and Cheryan (2017) explain, people of color in the U.S. are primarily marginalized along two dimensions within America’s racial order: how inferior-superior and how foreign-American are they considered to be? As reflected in Fig. 1, Whites are positioned as the most superior and American racial group. In contrast, while Black and Latino individuals are both stereotyped as inferior with respect to Whites, Black people are construed as a more American minority than Latinos and Asians (Carter, 2019). In turn, while Asian Americans and Latinos are both stereotyped as foreigners, Asian individuals are considered more superior than both Latinos and Blacks, as indicated by the model minority myth (Kim, 2000; Tuan, 1998; Xu & Lee, 2013).

Two axes of subordination. Note Adapted from Zou and Cheryan’s (2017) Racial Position Model (RPM)

This variance in social positions suggests that America’s hierarchy contains some keys to greater collective mobilization between people of color. For example, although Asian Americans are deemed a superior minority and Latinos are construed as an inferior group, individuals from both communities are often stereotyped as perpetual foreigners (Kim, 2000; Reny & Barreto, 2020; Zou & Cheryan, 2017). As Tuan explains (1998, p. 37), “Asian Americans are still treated as illegitimate Americans”, even while their “material success has…hastened greater resentment.” This meshes with the observations of Celia Lacayo (2017, p. 568), who highlights that “[b]oth Latinos and Asian Americans are often seen as foreigners and outsiders. But unlike Asians, Latinos are not afforded the benefits of being perceived as a model minority.” Together, these insights suggest that focusing on shared sources of marginalization might increase a sense of pan-racial solidarity between distinct minoritized groups, as our second opening epigraph indicates.

But even if common sources of marginalization can foster a greater sense of solidarity between minoritized groups, explaining how this translates to shared political views and action is complicated by a weak grasp of the psychology behind people of color (Pérez, 2021a; Pérez & Vicuña, 2022). An extensively replicated finding in psychology and political science is that co-existence of two categories typically unravels into the formation of an ingroup and outgroup (Pérez, 2015; Tajfel et al., 1971; Turner et al., 1987). By this account, members of the ingroup are motivated to distance and differentiate themselves from an outgroup to preserve what makes them special or unique (Brewer, 1991), thus allowing them to enhance their sense of self-worth. This distinctiveness motive leads individuals to engage in ingroup favoritism: a behavioral and attitudinal bias toward ingroup members. In fact, this process can intensify when groups resemble each other in terms of attributes and status, as often occurs between minoritized groups (e.g., Huddy & Virtanen, 1995). This insight suggests it is quite difficult for distinct racial minorities to achieve shared political goals.

Yet this same body of work also contains the seeds needed to explain how different ingroups might feel a greater sense of solidarity. This begins with recognition that many distinct ingroups share larger categories that encompass them and minimize perceptual differences between them (Gaertner et al., 1999). For example, although Whites and Blacks are unique racial groups, both share membership as American (Transue, 2007). Similarly, although Asians and Latinos are distinct racial and ethnic groups, they both consider themselves people of color (Pérez, 2021a). This suggests that the very same principles that guide ingroup favoritism at a subgroup level (e.g., Asians vs. Latinos) can be re-directed to achieve greater ingroup favoritism at a superordinate level (i.e., as people of color). Indeed, shifting one’s perspective toward a larger shared group causes perceived differences between distinct ingroups to recede, while bringing commonalities into sharper focus (Levendusky, 2018; Pérez, 2021a; Transue, 2007). This aligns with ongoing research on the social psychology of coalition-building among minoritized groups (Cortland et al., 2017; Craig & Richeson, 2012), which reveals that shared experiences serve to bond individuals and direct them toward common views and goals. It is also highly consistent with work by Sirin et al., (2017, 2021), who illuminate the affective role of empathy in bonding diverse individuals (see also Pérez, 2021a).

Finally, tracing the formation of solidarity among people of color and its political implications requires isolating the psychological chain reaction that connects solidarity to shared political views among minoritized groups. As Olson (1965) and other scholars (Van Zomeren et al., 2004) remind us, collective action among diverse individuals is a herculean feat. Politics is a peculiar domain, one that is relatively distal from people’s more immediate personal concerns and tastes (Lippmann, 1922). Hence, individuals generally display low levels of engagement with civic affairs: the central object of this realm (Zaller, 1992). This insight encourages scholars to grapple with the cognitive and affective processes that can awaken individuals from this torpor—processes that makes politics a more proximate consideration worthy of personal investment (e.g., Leach et al., 2008; Pérez, 2021a; Sirin et al., 2021). Here, Donald Kinder and others teach us that when racial and ethnic groups are salient in political discourse, people’s engagement with politics increases (Kinder & Kam, 2009; Nelson & Kinder, 1996; Winter, 2008), a phenomenon known as group-centrism.

In terms of solidarity driving interminority politics, this discussion suggests a two-step process. The first link in this chain reaction anticipates a strong connection between public discourse and heightened solidarity among people of color. Unlike racial or ethnic identities, which are deemed relatively stable and, therefore, hard to shift (Ellemers et al., 1997), solidarity is a context-specific variable that is responsive to intergroup cues (e.g., McClain et al., 2009; Pérez, 2021b). As Leach and his associates explain (2008, p. 147), solidarity captures one’s sense of bond and commitment to an ingroup in an immediate situation and is “associated with approaching the ingroup and group-based activity.” Insofar as solidarity between PoC is increased, the second link in this progression anticipates a downstream connection between heightened solidarity and the political views of minoritized individuals. The principal benefit of this mediated process is that it brings to light some of the inner workings in that “black box” that is the political psychology of people of color (Pérez & Vicuña, 2022).

Drawing on these insights, we argue that greater political unity among people of color depends on a heightened sense of solidarity between assorted minoritized groups. Whether this solidarity is triggered, we claim, rests on the degree to which public discourse highlights shared wellsprings of marginalization between communities of color. Insofar as distinct minoritized groups can better appreciate some of the common ways in which they are collectively oppressed, their sense of shared purpose should increase, with downstream consequences for their political views. Accordingly, we stipulate three hypotheses.

First, given the variance in social positions between minoritized groups, we expect baseline differences in their expressed solidarity with PoC (H1a). When two minoritized groups occupy different ends on a dimension in America’s racial hierarchy (superior vs. inferior), the higher-stationed group (e.g., Asians) should express less baseline solidarity with PoC than the lower-stationed group (e.g., Latinos), which reflects an effort to preserve one’s relative advantage on said dimension. In turn, we anticipate that higher levels of solidarity with PoC will increase individual support for policies that strongly implicate minority groups that are not one’s own (H1b).

Second (H2), we predict that exposure to discourse highlighting a source of marginalization that is shared with another minoritized group will heighten one’s sense of solidarity with other people of color. Third (H3), we anticipate that in light of this heightened solidarity, PoC will express greater support for policies that do not directly implicate their own group—evidence that solidarity leads diverse individuals to internalize common political goals and be more inclined to work toward them.

We test our hypotheses with two (2) surveys and two (2) experiments with Asian American (N = 1789) and Latino (N = 1765) adults. The surveys we use contain appropriate measures of solidarity with PoC, as well as measures of policies in two domains that are strongly associated with Asian Americans (i.e., legal immigration) and Latinos (i.e., unauthorized immigration). We find that Asian adults report reliably lower levels of solidarity with PoC than Latinos. This is consistent with the view that, despite being stereotyped as foreigners and un-American, Asian individuals are also stereotyped as a superior group compared to Latinos (e.g., Asians as model minorities) (see Fig. 1). In addition, we find that notwithstanding this gap, higher levels of solidarity with PoC increases Asian and Latino support for policies associated with communities of color that are not their own.

We refine these insights with two parallel experiments, which allocated Asian and Latino adults to a control group or treatment. Participants in the latter read about the marginalization of another community of color (Latinos or Asians) based on their alleged foreigness. That is, Latino adults read about Asian Americans, while Asian adults read about Latinos. Post-treatment, all participants answered questions about their sense of solidarity with PoC, followed by items capturing their views about admissions for high-skill immigrants (which implicates Asian Americans) and opinions about reducing unauthorized immigration (which implicates Latinos). We find clear evidence of our theorized chain reaction. Asian Americans and Latinos who were exposed to treatment report greater solidarity with people of color, which then substantially increases support for policies that do not directly implicate one’s racial group (but do implicate the group they read about). This means that Asian Americans who feel more solidarity with PoC become substantially more supportive of flexible policies toward unauthorized immigrants, while Latinos who feel more solidarity with PoC become significantly more supportive of generous policies toward high-skill immigrants.

Study 1: Varied Solidarity and Political Views Among Asian and Latino Adults

Our first layer of evidence draws on a reanalysis of the Asian and Latino samples of the “People of Color” surveys reported in Pérez (2021a).Footnote 1 Each sample consists of 1200 adults from each group, weighted to census benchmark for a population. While these are non-probabilistic surveys, they are widely heterogeneous samples and include relevant measures for some key variables in our theoretical framework. Specifically, these surveys contain measures of solidarity with people of color, support for Deferred Action on Childhood Arrivals (DACA) (which implicates Latinos), and support for visas awarded to legal immigrants (which implicates Asian Americans) (Malhotra et al., 2013; Pérez, 2021a). Each sample also contains a brief suite of demographic and political variables (e.g., ideology, nativity), which we use as covariates. The wording for all covariates is in our supplementary information, section 1 (SI.1).

We appraise political solidarity with two statements completed on a scale from 1-strongly disagree to 7-strongly agree. These items were “I feel solidarity with people of color” and “People of color have a lot in common with each other,” both of which have been validated by prior work (cf. Leach et al., 2008). We combine these items into an additive scale that averages the replies provided by individual respondents (r = .525). Using the same response scale, we gauged support for flexible policy toward undocumented immigrants with a single item about DACA (Deferred Action on Childhood Arrivals). Here, respondents replied to a statement about “renewing temporary relief from deportation for undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. as children.” In turn, we gauged support for legal immigration policy with another single item about “increasing the number of visas available to legal immigrants.”

Our first hypothesis anticipates measurable differences in expressed solidarity with PoC between Asian and Latino adults (H1a). We derive this prediction from each group’s location in America’s racial order (see Fig. 1), where Asian individuals are considered a more superior group than Latinos, despite both groups being stereotyped as foreign and un-American. The specific position of Asian individuals with respect to Latinos is such that the former is considered relatively more superior than the latter. Thus, we expect that Asian individuals will display lower baseline levels of solidarity than Latinos as a way to preserve their relatively higher status on this dimension. Indeed, consistent with this view, Craig and her collaborators (2021) show that Asian individuals are more likely to build political coalitions with Whites when considering issues that implicate allegedly inferior groups, like Latinos and African Americans. In addition, we hypothesize that, net of any baseline differences in solidarity with people of color, higher levels of this variable will positively correlate with Asian and Latino support for policies that strongly implicate another minoritized community (H1b). To this end, we pool these samples and estimate the raw racial difference in each of these outcomes, while holding constant individual differences in our suite of covariates. The key variables in these analyses are coded so that higher values reflect greater quantities of a construct. We estimate OLS models, with all coefficients on a 0–1 interval to permit comparisons. Table 1 reports the relevant results.

There we see under column 2 that in comparison to Latino respondents, Asian American respondents report reliably less solidarity with people of color (− .042, p < .001, two-tailed). This result aligns with (H1a), which predicts that Asian Americans’ relatively more superior status in America’s racial hierarchy should yield lower average levels of solidarity than an allegedly inferior group, like Latinos (e.g., Zou & Cheryan, 2017). Equally important, this pattern is independent of individual differences in various demographics, as well as political ideology. We find this latter trend especially informative, since it suggests that the observed gap in expressed solidarity between these two minoritized groups is not driven by possible differences in the degree to which individuals in each group generally expresses “progressive” political views.

Is this variation in expressed solidarity with PoC associated with Asian and Latino support for policies that do not strongly implicate them? Some of the evidence in Table 1 suggests it is. First, we find that in comparison to Latino adults, Asian American adults are reliably less supportive of DACA (− .053, p < .001, two-tailed)—a proposal strongly associated with Latinos. Nevertheless, this gap in support is rivaled by expressed solidarity with PoC, which is significantly correlated with greater support for this policy initiative, thus affirming (H1b). In an initial analysis that we report in SI.2, we find that the association between solidarity and each outcome is not moderated by one’s racial/ethnic classification as Asian versus Latino. Table 1 therefore reports pooled associations that capture the relationship between solidarity and each outcome across Asian American and Latino adults in this survey. This lets us to see that a shift from the lowest to highest level of solidarity with PoC is reliably associated with stronger support for DACA among Asian Americans and Latinos (.362, p < .001, two-tailed). Hence, notwithstanding racial differences in support for DACA (see column 3), a greater sense of solidarity with PoC is associated with greater support for this policy among both Asian American and Latino adults in our sample.

Turning to the realm of legal immigration, we uncover comparable evidence to what we just reported, but with one wrinkle. In a domain that, we argue, strongly implicates Asian Americans, we still observe a negative correlation between being Asian American and support for increasing visas for legal immigrants. This gap is numerically smaller than what we observed in our analysis of DACA preferences, yet this difference between coefficients is statistically indistinguishable from zero. We think this unexpected pattern might be due to a looser correspondence than anticipated between the wording of our legal immigration item and the high-skill nature of legal immigration that implicates Asian Americans, since our item here does not expressly make that connection (Malhotra et al., 2013). We investigate this further in Studies 2–3.

Finally, setting aside this result for now, we again see that greater reported solidarity with PoC is positively associated with Asian and Latino support for legal immigrant visas (.282, p < .001, two-tailed), thus further underlining the role that solidarity with people of color might play in unifying political opinions among assorted minoritized groups. In short, despite racial differences in support for visas for legal immigrants, a stronger sense of solidarity with PoC is associated with greater support for this policy initiative among Asian American and Latino adults in this sample. In SI.2, we again show that this connection between solidarity and support for visas for legal immigrants does not vary reliably by whether one is Asian American or Latino.

Study 2: Heightening Latino Solidarity with PoC and Forging Political Unity with Asian Americans

Study 1 provides correlational evidence that generally aligns with our perspective on two key fronts. First, consistent with our proposed framework, we find that, at baseline, Asian Americans and Latinos report reliably different levels of expressed solidarity with people of color. This difference in solidarity is consistent with our reasoning about the varied social positions of minoritized groups in America’s racial order (see Fig. 1). Second, our analysis suggests that, at least on the issue of undocumented immigration, Latino adults are, as expected, more supportive of flexible policy in this domain than Asian Americans. Nonetheless, there are at least two blind spots in this analysis. The first one is that in the realm of legal immigration, which we claim strongly implicates Asian Americans, adults from this population reported mildly lower (not higher) levels of support in this domain. We attribute this to the imprecise wording of our legal immigration item in that analysis, which did not emphasize the high-skill flows of legal immigrants most strongly associated with Asian Americans (cf. Malhotra et al., 2013). Second, and perhaps more importantly, we have yet to find evidence that differences in solidarity with PoC can be bridged and become directly consequential for politics. Study 2 begins to address these two points.

In partnership with Dynata, an online survey platform, we recruited a sizeable sample of Latino adults (N = 624) to participate in a brief 8-min survey. After consenting to participate, Latino respondents answered a few demographic questions (e.g., age, gender, education, nativity) (see SI.1 for question wording and balance checks). Following this, participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions. Drawing on prior work (Hopkins et al., 2020), our control group exposed participants to an article depicting the gradual extinction of giant tortoises. In turn, participants in the treatment condition read an article of comparable length that described continued discrimination against Asian Americans (see page 8, SI.1).

Our manipulation was presented as a news brief about “Asians’ Decades-Long Exclusion in the U.S.” The article highlights the continued prejudice and discrimination that Asian individuals experience as perpetual foreigners, similar to many Latinos.

In this way, we manipulate a sense of similarity in discrimination experiences between groups, not similarity in identity, which aligns with our proposed mechanism and is consistent with prior work showing how highlighting intergroup similarity is sufficient to trigger a sense of commonality between diverse individuals (e.g., Cortland et al., 2017; Pérez, 2021a). Hence, our treatment article overwhelmingly centers around the Asian experience with racism, while making two passing connections to a similar experience among Latinos. In a paragraph consisting of 245 words, 2 of them refer to “Latinos”, which is 1% of the total. An effect from this treatment will suggest that a link between one’s ingroup and another minoritized outgroup must be made in order for solidarity to reliably increase.

To ensure that individuals were, in fact, treated, Latino participants completed a manipulation check asking them to indicate whether “The information I read highlighted how Asian Americans are still viewed as not fully American.” Fifty-nine (59) participants failed this manipulation check, which is about 9% of our sample. We exclude these participants from our analyses, although including them does not alter the substantive conclusions we draw from these data, but does make our estimates less precise given the “noise” that inattentive respondents introduce (SI.3).

Following our manipulation check, participants completed two (2) statements designed to capture our mediator, solidarity with people of color, with one item being reverse-worded in order to mitigate possible acquiescence bias. This particular statement read “The problems of Blacks, Latinos, Asians, and other minorities are too different for them to be allies or partners.” Both items were answered on a scale from 1-strongly disagree to 5-strongly agree. We code and scale them so that higher values reflect a stronger sense of solidarity with PoC.Footnote 2

Following appraisal of our mediator, we administered a pair of two-item batteries gauging support for an easier admissions process for high-skill immigrants, a domain that strongly implicates Asian Americans (e.g., Malhotra et al., 2013; Pérez, 2021a); and support for more flexible policies toward unauthorized immigrants, a realm that strongly implicates Latinos (e.g., Pérez, 2016; Valentino et al., 2013). For example, one of the items gauging support for high-skill immigrants asked participants to indicate their degree of agreement with “Increasing the number of H1-B visas, which allow U.S. companies to hire people from foreign countries to work in highly skilled occupations, such as engineering, computer programming, and high-technology.” This wording, we believe, should tap more precisely into the connection between legal immigration and Asian American immigrants. In the realm of unauthorized immigration, one of the items captures support for undocumented immigrants by asking participants to indicate the extent to which they support “increasing the number of border patrol agents at the U.S.-Mexico border”, which is reverse-worded and focuses on America’s southern border in order to link it more directly to Latinos. All four of these policy items (SI.1) were completed on a scale from 1-strongly disagree to 5-strongly agree. We combine each pair of items into additive indices so that higher values reflect greater support for flexible immigration policies in each domain. This has the added virtue of attenuating measurement error in our estimation (Brown, 2007).Footnote 3 In our analyses, all variables run along a 0 to 1 interval, thus allowing us to interpret our OLS coefficients as percentage-point shifts.

Study 2’s Results

In our mediation analysis here, the essential step is establishing the connection between our treatment and expressed solidarity between people of color. Earlier renditions of mediation analyses (Baron & Kenny, 1986) suggested that a direct effect was necessary to establish a mediation pattern. Across nearly 4 decades, methodologists in psychology have discovered that such direct effects are neither necessary, nor sufficient (Hayes, 2021; Igartua & Hayes, 2021; Zhao et al., 2010). What is essential is for a treatment to reliably affect a mediator; and, for a mediator to influence an outcome(s). Given that prior work suggests liberal ideology is a key influence on the attitudes of people of color (Pérez, 2021a), we include a pre-treatment measure of this variable as a covariate to ensure that any association between solidarity and our outcomes is independent of the influence of liberal ideology.

Table 2 displays the key result for this part of our analysis. In panel A, we see that relative to the control, Latinos who read about the continued marginalization of Asian Americans as perpetual foreigners reliably increased their sense of solidarity with people of color by about 5 percentage points (.049, p < .013): a measurable effect that is substantively meaningful. What happens in light of this shift in solidarity with PoC among Latinos? As the third column in Table 2 reveals, this heightened sense of solidarity leads Latino adults to substantially increase their support for flexible policies toward unauthorized immigrants (.258, p < .001, two-tailed), which is a large increase of nearly 26 percentage points, net of the influence of liberal ideology (.168, p < .001).

More importantly, perhaps, panel B in Table 2 reveals comparable effects for support of flexible policy toward high-skill immigrants: a domain that strongly implicates Asian Americans. Relative to our control, our perpetual foreigner treatment increases Latino solidarity with people of color by about 5 percentage points (.049, p < .013). In turn, this sharpened sense of solidarity also leads Latino adults to express significantly more support for policies that benefit high-skill immigrants (.286, p < .001)—an effect that, again, is independent of the influence of liberal ideology (.125, p < .002). These patterns imply that the heightened sense of solidarity Latinos feel in this experiment leads them to support more flexible policies in each domain at comparable levels, even though the realm of high-skill immigration strongly implicates Asian Americans.

Further analysis of these indirect effects from treatment, to solidarity, to policy support suggests they are reliably different from zero, thus providing additional validation of this proposed pathway, which we depict in Fig. 2.Footnote 4 There we see that our treatment works entirely through our proposed mediator, solidarity with people of color. Specifically, exposure to Asians’ continued marginalization as perpetual foreigners leads Latino adults to express more solidarity with PoC, which then heartily increases their support for flexible policies aimed at unauthorized and high-skill immigration.

In addition to adjusting our mediation estimates for liberal ideology, we also follow the advice of some methodologists (e.g., Imai & Yamamoto, 2013; Zhao et al., 2010) by conducting sensitivity analyses on the downstream paths displayed in panels A and B (Fig. 2). These tests estimate how large the error correlation (ρ, rho) between our mediator and an unmodeled confounder must be in order for this downstream association to be completely compromised. In our supplementary information (SI.5), we show that the connection between heightened solidarity with PoC and each of these outcomes vanishes to zero when ρ ≥ .26, which reflects a moderate degree of robustness. This sensitivity analysis, coupled with the inclusion of ideology as a covariate, increases confidence in our observed mediation pattern. We revisit these findings in our conclusion and discuss what they imply for future research on the bonding role of solidarity among PoC.

Study 3: Same Pathway, Different Community of Color (Asian Americans)

Study 2 established that Latino adults who read about the continued marginalization of Asians as perpetual foreigners expressed significantly more solidarity with all people of color—including Asian Americans. In turn, this heightened sense of a common bond with other racially minoritized individuals was reliably and robustly associated with large downstream increases in Latino support for policies that implicate their own pan-ethnic group, as well as a racial outgroup (i.e., Asian Americans). Yet a crucial question remains: to what extent is this observed dynamic replicable and applicable beyond Latino adults? To answer this, we undertook Study 3, which appraised the same chain reaction from shared marginalization, to solidarity with PoC, to shared political views among Asian American adults (N = 641): a major minoritized group, whose politics generally receive less attention in the literature on racial politics (Wong et al., 2011).

Study 3 was identical in terms of platform, structure, and sequence to the one behind Study 2. The only difference between Study 3 and the previous experiment is our focus on Asian American adults (N = 641), which means that our treatment here exposes members of this racial group to information about how Latinos continue facing marginalization as perpetual foreigners (see page 7 in S.1 for treatment wording). This 245-word treatment overwhelmingly focused on Asians, with 1% of the word total referencing Latinos. Hence, an effect from this treatment will also suggest that a link between one’s ingroup and another minoritized outgroup must be made in order for solidarity to reliably increase.

As in our prior experiment, our analysis here focuses on Asian participants who passed our manipulation check and appraises the links from treatment to solidarity to political views about legal immigration for high-skilled workers and opinions about unauthorized immigration.Footnote 5 Fifty-two (52) participants failed this manipulation check or 8% of our sample. We exclude these participants from further analysis, although our inferences remain substantively unchanged if we include them (SI.3). In addition, we once again include liberal ideology as a covariate. All variables again run on a 0–1 interval to facilitate interpretation.

Study 3’s Results

Do Asian Americans express greater solidarity with PoC when primed with information about the marginalization of Latinos as perpetual foreigners? The results in Table 3 suggest they do. Panel A indicates that compared to our control group, Asian Americans who read about the systematic marginalization of Latinos as foreign and un-American expressed a stronger sense of solidarity with PoC—a reliable increase of about 4 percentage points (.044, p < .011, two-tailed). In turn, an increase in solidarity with PoC is associated with a nearly 20 percentage point increase in Asian support for policies toward high-skilled immigration (.195, p < .001, two-tailed), independently of the influence of liberal ideology (.163, p < .001).

More importantly, perhaps, when we turn to support for flexible policy toward undocumented immigrants, we find that exposure to treatment increases Asians expression of solidarity with PoC by about 4 percentage points (.044, p < .011, two-tailed). In turn, a unit increase in solidarity with people of color is associated with an increase in Asian American support for more flexible policy toward undocumented immigrants by nearly twenty-three percentage points (.227, p < .001, two-tailed), a pattern that is also independent of the influence of liberal ideology (.329, p < .001, two-tailed). Similar to the results we uncovered in our experiment on Latinos, the indirect effects reported here are also reliably different from zero.Footnote 6

We depict in Fig. 3 the mediation process we uncover in our Asian sample. There we see that our treatment works completely through our hypothesized mediator, solidarity with people of color. In particular, exposure to Latinos’ marginalization as perpetual foreigners causes Asian American adults to express more solidarity with people of color, which then substantially increases their support for flexible policies aimed at unauthorized and high-skill immigration.

In line with our analysis of Study 2, we also assess here the sensitivity of our mediation result to possible confounding. Recall that this test appraises how large the error correlation (ρ, rho) between our mediator and an unmodeled confounder must be in order for this downstream association to be compromised. In S.5, we show that this downstream path has a moderate degree of robustness to confounding as well, with ρ ≥ .17–.21, a value that is net of the inclusion of liberal ideology as a covariate (Pérez, 2021a). We return to this issue in the conclusion and discuss its implications for additional theoretic innovations going forward.

But before getting to our conclusion, let us address one last major point. Our framework anticipates that in light of heightened solidarity, people of color will express more unified political views. With our results from our two experiments in hand, we now have the evidence needed to speak more directly to this point. As Fig. 4 reveals, in the absence of solidarity with people of color (light-gray bars), Latino (.368, 95% CI .311, .425) and Asian (.282, 95% CI .222, .342) support for flexible policy toward unauthorized immigrants varies appreciably in the expected direction, with Asian Americans expressing less of it (− .086, p < .05, one-tailed), consistent with expectations. In turn, as the dark bars indicate, a unit-increase in solidarity with PoC increases Latino support for flexible policy toward the unauthorized to .644 (95% CI .611, .678) and Asian support for these initiatives to .616 (95% CI .579, .653), which yields a negligible difference between both groups (− .028, p > .05, one-tailed).

Figure 5 reveals a similar pattern when we turn to the realm of support for flexible policy toward high-skill immigration. In the absence of solidarity with PoC (light-gray bars), Latinos, as expected, report marginally less support for this policy domain (.475, 95% CI .413, .537) than their Asian American counterparts (.530, 95% CI .471, .589) (− .055, p < .06, one-tailed). However, in light of a unit increase in solidarity with people of color, the gap in support for flexible policy toward high-skill immigrants between Latinos (.774, 95% CI .737, .810) and Asians (.779, 95% CI .742, .816) narrows to a negligible one (black bars, − .005, p > .05, one-tailed). Together, these findings suggest that highlighting a shared source of marginalization helps to unify public opinion among people of color through a heightened sense of solidarity with other minoritized groups.

Implications

Across three studies with Asian American and Latino adults, we find clear evidence for key tenets in our proposed framework. Specifically, we showed that, at baseline, Asian Americans and Latinos differ in the degree to which they sense solidarity with other people of color—and the extent to which they are inclined to support polices that do not immediately implicate their ingroup. These results reflect each group’s positioning in America’s racial order and underlines each group’s “natural” parochial stance, where one’s ingroup is the default frame of reference for the political world (e.g., Kinder & Kam, 2009). We then showed how this narrower view toward “one’s own” can be broadened by training Asians’ and Latinos’ attention on a shared source of marginalization between these distinct groups. As our experiments revealed, a sense of similar marginalization reliably increases Asians’ and Latinos’ solidarity with people of color, which then boosts support for policies that strongly implicate other racial outgroups. Of course, our findings are based on a manipulation that compactly highlighted similarity in discrimination experiences between groups (Cortland et al., 2017; Pérez, 2021a). Whether other manipulations with greater or lesser detail can spark the same reaction is both a theoretical and empirical matter, and one that can enhance the external validity of our results (i.e., similar effects across different participants, settings, and operationalizations of our treatment) (Campbell & Stanley, 1963). We welcome future research that builds in this direction.

How can our findings forge additional insights? An extensive literature on interminority politics already highlights various circumstances under which we observe greater conflict between minoritized communities in the U.S., with less emphasis on the conditions under which interminority cooperation emerges (Benjamin, 2017; McClain & Karnig, 1990; McClain et al., 2007; Wilkinson, 2015). Our work unifies these perspectives by highlighting some psychological pathways that shape when and why we observe conflict or cooperation between communities of color. On the side of conflict, previous work has strongly underscored the role of zero-sum perceptions over finite material sources (e.g., jobs, schools) (Carey et al., 2016; McClain et al., 2007; Wilkinson, 2015). Our work suggests that, even in absence of intergroup competition, interminority unity is difficult to accomplish because of their varied positions within America’s racial order (Zou & Cheryan, 2017). These positions, we have argued, are underpinned by unique forms of marginalization, which makes the cementing of intergroup differences difficult to accomplish.

Yet by placing America’s racial hierarchy front and center, our findings also reveal how the stratification of minoritized groups presents unique psychological possibilities for distinct communities of color to express more unified political views. For all of the differences that separate various communities of color (e.g., Carter, 2019; Kim, 2000; Masuoka & Junn, 2013; Tuan, 1998), America’s racial order also presents unique opportunities for greater cooperation—opportunities that are rooted in some of the similar ways that various PoC are marginalized (Zou & Cheryan, 2017). In this way, our findings suggest that the absence of interminority cooperation in some settings can be attributed, in part, to weak or unimaginative efforts at connecting various non-White groups through some of the ways that they, collectively, experience a form of second-class citizenship (Cortland et al., 2017; Pérez, 2021b).

What do our findings suggest about where to go next? In the interest of space, we focus on two areas directly implied by our results. Our experiments establish, with a reasonable degree of confidence, that the link between shared marginalization, solidarity with PoC, and more unified political opinions among minoritized groups is a viable one. But viable does not mean exclusive. As indicated by our sensitivity analyses in Studies 2 and 3, the possibility of additional mediators is a real one. This is a question of enhancing our theoretical grasp of the psychological pathways that foster greater interminority comity in some circumstances. One possibility is that the connection between shared marginalization and broader political unity is incrementally more involved than our proposed process indicates. The idea here is not that solidarity with PoC is the “wrong” mediator, but that the chain reaction we uncovered might be more cognitively involved than what we found. Since solidarity with others is but one component of collective action between diverse individuals (Leach et al., 2008), there are related elements that plausibly enhance this process.

For example, if, as we have established, shared marginalization causes a heightened sense of solidarity with PoC, it is possible that this effect also leads minoritized individuals to perceive themselves as part of a broader group (i.e., people of color). Such perceptions can manifest as self-stereotyping—one’s recognition that, in an immediate context, one is part of salient group (Turner et al., 1987). Indeed, prior work suggests self-stereotyping and solidarity are positively correlated at a level that is consistent with the results of our sensitivity analyses (Leach et al., 2008), thus implying that feeling solidarity leads one to perceive commonality with people of color, with downstream consequences for their political views. The intricacy of this psychology is something that is beyond the scope of our current set of studies. But by establishing a blueprint, we are in an improved position to learn more and with greater nuance. As America’s demographics continue to quickly evolve, we see such efforts as an ongoing necessity, rather than merely an academic curiosity.

Second, our results enhance our knowledge of political coalition-building in an increasingly diverse polity (e.g., Cortland et al., 2017). In elections where partisanship is a major force, our findings suggest the psychological process we uncovered can be harnessed to galvanize voters of color. Although PoC generally identify as Democrats (Anoll, 2021; Fraga, 2018; White & Laird, 2020), identification with a party is not the same thing as mobilization on its behalf. This is especially true among Democrats, who sometimes underperform electorally due to internecine political conflicts between different racial constituencies within the party (Pérez et al., 2021). This implies that heightening a sense of solidarity among people of color through perceived similarity might help reduce these conflicts to better ensure that non-White Democrats feel like true stakeholders in their party’s fortunes. A close reading of our treatments in both studies also implies that political elites must make this connection crystal clear for people of color, rather than assume that this linkage will happen spontaneously. Indeed, in the absence of any verbal linkage between one’s ingroup and another minoritized outgroup, it seems unlikely solidarity will increase.

This anticipated electoral benefit is particularly promising in non-partisan local elections (e.g., Benjamin, 2017). In the absence of strong partisan cues, candidates must devise strategies that mobilize potential voters on the basis of non-partisan attributes. In major cities, where such electoral contests take place, various communities of color often compete for political representation on the basis of their own unique racial or ethnic group (Benjamin, 2017; Wilkinson, 2015). Thus, championing political issues that tap into a sense of similar marginalization (e.g., anti-immigrant policies and procedures) can help steer interminority politics away from a conflictual course and more toward a cooperative path, including one that increases the number of elected officials of color.

We think this can be accomplished, in part, by expanding the circle of solidarity we have uncovered. The principle behind the effects reported in this paper is one of perceived similarity in terms of discrimination experiences (e.g., Cortland et al., 2017; Pérez, 2021a; Zou & Cheryan, 2017). Similar to does not mean exactly as, however. It is the comparability of group experiences with discrimination that provides the cognitive flexibility to connect disparate groups toward a more unified political purpose(s). One useful extension here, then, is to see whether this similarity principle can be used to build broader coalitions of non-Whites by drawing on groups who are not typically construed as foreign. For example, although African Americans are stereotyped as the least foreign minority in America’s racial landscape (Zou & Cheryan, 2017), such stereotypes, by definition, minimize variance in this attribute. Nevertheless, growing research finds that the very contours of the African American population have expanded to include increasing numbers of Caribbean and African immigrants (Deaux, 2005; Greer, 2013; Smith, 2014). This heterogeneity lends itself to further coalition-building between immigrant minorities that cut across racial or ethnic categories (e.g., African Americans, Asian Americans, and Latinos), with perceived similarity in discrimination experiences as the mechanism.

Data Availability

Upon publication, data will be deposited in Harvard’s Dataverse.

Code Availability

Upon publication, all code will be posted on Harvard’s Dataverse.

Notes

All data and code necessary for replication purposes can be found on Political Behavior’s Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/KLRTHN.

These items correlate positively, but modestly (ρ = .09), likely because of the reverse-worded item. Nonetheless, we scale these items based on their prior validation (cf. Leach et al., 2008) and because we expected them to correlate positively, which they do, albeit weakly. Our predicted effects generally emerge if we only use either item as a mediator, but with mixed precision (SI.4). This further affirms our decision to scale these items to reduce measurement error (Brown, 2007).

Legal immigration items (ρ = .56). Undocumented immigration items (ρ = .11). Again, the positive, but low, correlation here is likely due to our reverse-worded item in this latter pair. Our estimates generally do not differ, directionally, if we model single items instead, but their statistical precision is mixed (S.4).

We assess the significance of these indirect paths by estimating the Average Causal Mediation Effect (ACME). This allows us to generate 95% confidence intervals for each indirect effect. Each indirect effect in Table 2 (panels A and B) is reliably different from zero (ACME—unauthorized immigration: .014, 95% CI .003, .026; ACME high-skill immigration: .015, 95% CI .003, .028).

The correlation between our solidarity items is again positive, but modest (ρ = .132), which we attribute to our reverse-worded item. Consistent with this reasoning, the correlation between our undocumented immigration items (one of which is reverse-worded) is also positive and moderate in size (ρ = .265). Finally, the correlation between our legal immigration item pair is positive and substantial (ρ = .658). We draw the same directional inferences if we use single items to assess our mediator and outcomes (SI.4).

We again estimate the ACMEs for each outcome under analysis: (high-skill immigration: .010, 95% CI .001, .017; undocumented immigration .010, 95% CI .002, .019).

References

Anoll, A. (2021). The obligation mosaic: Race and social norms in US political participation. The University of Chicago Press.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Benjamin, A. (2017). Racial coalition building in local elections: Elite cues and cross-ethnic voting. Cambridge University Press.

Bobo, L., & Hutchings, V. L. (1996). Perceptions of racial group competition: Extending Blumer’s theory of group position to a multiracial social context. American Sociological Review, 61(6), 951–972.

Brewer, M. B. (1991). The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17(5), 475–482.

Brown, T. A. (2007). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford publications.

Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1963). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Rand McNally & Company.

Carey, T. E., Jr., Martinez-Ebers, V., Matsubayashi, T., & Paolino, P. (2016). Eres Amigo O Enemigo? Contextual determinants of Latinos’ perceived competition with African-Americans. Urban Affairs Review, 52(2), 155–181.

Carter, N. M. (2019). American while Black: African Americans, immigration, and the limits of citizenship. Oxford University Press.

Cortland, C. I., Craig, M. A., Shapiro, J. R., Richeson, J. A., Neel, R., & Goldstein, N. J. (2017). Solidarity through shared disadvantage: Highlighting shared experiences of discrimination improves relations between stigmatized groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(4), 547–67.

Craig, M. A., & Richeson, J. A. (2012). Coalition or derogation? How perceived discrimination influences intraminority intergroup relations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(4), 759–777.

Craig, M. A., Zou, L. X., Bai, H., & Lee, M. M. (2021). Stereotypes about political attitudes and coalitions among US racial groups: Implications for strategic political decision-making. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672211037134

Deaux, K. (2005). To be an immigrant. Russel Sage Foundation.

Ellemers, N., Spears, R., & Doosje, B. (1997). Sticking together or falling apart: In-group identification as a psychological determinant of group commitment versus individual mobility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(3), 617.

Fraga, B. L. (2018). The turnout gap: Race, ethnicity, and political inequality in a diversifying America. Cambridge University Press.

Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., Rust, M. C., Nier, J. A., Banker, B. S., Ward, C. M., Mottola, G. R., & Houlette, M. (1999). Reducing intergroup bias: Elements of intergroup cooperation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(3), 388–402.

Greer, C. (2013). Black ethnics: Race, immigrant, and the pursuit of the American dream. Oxford University Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2021). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

Hopkins, D. J., Kaiser, C. R., Pérez, E. O., Hagá, S., Ramos, C., & Zárate, M. (2020). Does perceiving discrimination influence partisanship among us immigrant minorities? Evidence from five experiments. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 7(2), 112–36.

Huddy, L., & Virtanen, S. (1995). Subgroup differentiation and subgroup bias among Latinos as a function of familiarity and positive distinctiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(1), 97–108.

Igartua, J.-J., & Hayes, A. F. (2021). Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: Concepts, computations, and some common confusions. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 24, e49.

Imai, K., & Yamamoto, T. (2013). Identification and sensitivity analysis for multiple causal mechanisms: Revisiting evidence from framing experiments. Political Analysis, 21(2), 141–171.

Kim, C. J. (2000). Bitter fruit: The politics of Black-Korean conflict in New York city. Yale University Press.

Kinder, D. R., & Kam, C. D. (2009). Us against them: Ethnocentric foundations of American opinion. University of Chicago Press.

Lacayo, C. O. (2017). Perpetual inferiority: Whites’ racial ideology toward Latinos. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 3(4), 566–579.

Leach, C. W., Van Zomeren, M., Zebel, S., Vliek, M. L., Pennekamp, S. F., Doosje, B., Ouwerkerk, J. W., & Spears, R. (2008). Group-level self-definition and self-investment: A hierarchical (multicomponent) model of in-group identification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(1), 144–65.

Levendusky, M. (2018). Americans, not partisans: Can priming American national identity reduce affective polarization? Journal of Politics, 80(1), 59–70.

Malhotra, N., Margalit, Y., & Mo, C. H. (2013). Economic explanations for opposition to immigration: Distinguishing between prevalence and conditional impact. American Journal of Political Science, 57(2), 391–410.

Masuoka, N., & Junn, J. (2013). The politics of belonging: Race, public opinion, and immigration. University of Chicago Press.

McClain, P. D., & Karnig, A. K. (1990). Black and Hispanic socioeconomic and political competition. American Political Science Review, 84(2), 535–545.

McClain, P. D., Lyle, M. L., Carter, N. M., Soto, V. M., Lackey, G. F., Cotton, K. D., Nunnally, S. C., Scotto, T. J., Grynaviski, J. D., & Kendrick, J. A. (2007). Black Americans and Latino immigrants in a southern city: Friendly neighbors or economic competitors? Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 4(1), 97–117.

McClain, P. D., Johnson Carew, J. D., Walton, E., Jr., & Watts, C. S. (2009). Group membership, group identity, and group consciousness: Measures of racial identity in American politics? Annual Review of Political Science, 12, 471–485.

Merseth, J. L. (2018). Race-ing solidarity: Asian Americans and support for Black lives matter. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 6(3), 337–356.

Nelson, T. E., & Kinder, D. R. (1996). Issue frames and group-centrism in American public opinion. The Journal of Politics, 58(4), 1055–1078.

Olson, M. (1965). The logic of collective action: Public goods and the theory of groups. Harvard University Press.

Omi, M., & Winant, H. (1986). Racial formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1980s. Routledge.

Pérez, E. O. (2015). Xenophobic rhetoric and its political effects on immigrants and their co-ethnics. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 549–564.

Pérez, E. O. (2016). Unspoken politics: Implicit attitudes and political thinking. Cambridge University Press.

Pérez, E. O. (2021a). Diversity’s child: People of color and the politics of identity. University of Chicago Press.

Pérez, E. O. (2021b). "(Mis)calculations, psychological mechanisms, and the future politics of people of color. Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics. https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2020.37

Pérez, E. O., Kuo, E., Russel, J., Scott-Curtis, W., Muñoz, J., & Tobias, M. (2021). The politics in White identity: Testing a racialized partisan hypothesis. Political Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12788

Reny, T. T., & Barreto, M. A. (2020). Xenophobia in the time of pandemic: Othering, anti-Asian attitudes, and Covid-19. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 10(2), 209–232.

Rodríguez-Muñiz, M. (2021). Figures of the future. Princeton University Press.

Sirin, C. V., Valentino, N. A., & Villalobos, J. D. (2017). The social causes and political consequences of group empathy. Political Psychology, 38(3), 427–448.

Sirin, C. V., Valentino, N. A., & Villalobos, J. D. (2021). Seeing us in them: Social divisions and the politics of group empathy. Cambridge University Press.

Smith, C. W. (2014). Black Mosaic: The politics of Black pan-ethnic diversity. New York University Press.

Tajfel, H., Billig, M., Bundy, R. P., & Flament, C. (1971). Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420010202

Transue, J. E. (2007). Identity salience, identity acceptance, and racial policy attitudes: American national identity as a uniting force. American Journal of Political Science, 51(1), 78–91.

Tuan, M. (1998). Forever foreigners or honorary whites? Rutgers University Press.

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Basil Blackwell.

Valentino, N. A., Brader, T., & Jardina, A. E. (2013). Immigration opposition among US Whites: General ethnocentrism or media priming of attitudes about Latinos? Political Psychology, 34(2), 149–166.

van Zomeren, M., Spears, R., Fischer, A. H., & Leach, C. W. (2004). Put your money where your mouth is! Explaining collective action tendencies through group-based anger and group efficacy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(5), 649–664.

White, I. K., & Laird, C. N. (2020). Steadfast democrats: How social forces shape Black political behavior. Princeton University Press.

Wilkinson, B. C. (2015). Partners or rivals? Power and Latino, Black, and White relations in the twenty-first century. University of Virginia Press.

Winter, N. J. G. (2008). Dangerous frames: How ideas about race and gender shape public opinion. University of Chicago Press.

Wong, J. S., Ramakrishnan, S. K., Lee, T., & Junn, J. (2011). Asian American political participation: Emerging constituents and their political identities. Russell Sage Foundation.

Xu, J., & Lee, J. (2013). Marginalized ‘Model’ minority: An empirical examination of the racial triangulation of Asian Americans. Social Forces, 91(4), 1363–1397.

Zaller, J. R. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge University Press.

Zhao, X., Lynch, J., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37, 197–206.

Zou, L. X., & Cheryan, S. (2017). Two axes of subordination: A new model of racial position. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112(5), 696.

Lippmann, W. (1922). The world outside and the pictures in our heads. In Public opinion (pp. 3–32). MacMillan Co.

Pérez, E. O., & Vicuña, B. V. (2022). The gaze from below: Toward a political psychology of minority status. In L. Huddy, D. O. Sears, J. Levy, & J. Jerit (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political psychology (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

US Census Bureau. (2020). 2020 census. Census.gov. Retrieved August 9, 2021, from https://www.census.gov/2020census

Acknowledgements

The research reported in the paper is based on a student research design submitted as a requirement in the first author’s course, Experiments in U.S. Racial and Ethnic Politics.

Funding

Financial support for the reported studies was provided by the Political & Psychological Science Incubator (PPSI) at UCLA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

The reported studies were conducted ethically, in accordance with guidelines from UCLA’s Institutional Review Board.

Consent to Participate

All participants formally provided their consent to participate.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pérez, E., Vicuña, B.V., Ramos, A. et al. Bridging the Gaps Between Us: Explaining When and Why People of Color Express Shared Political Views. Polit Behav 45, 1813–1835 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09797-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09797-z