Abstract

Conventional scholarly wisdom has held that the popularity/approval of political leaders is determined by a governments’ ability to provide peace, prosperity, and security to its citizens. However, for coalition governments in multiparty parliamentary democracies, popularity may also be shaped by legislative and structural divisions among ruling parties. Lower legislative cohesion may decrease the coalition’s political feasibility while structural divisions indicate that policy preferences in the government are diverse, and the government is more constrained to act on potentially divisive issues. These two factors are tested in the context of recent Israeli political history where prime ministers have been historically dependent on coalition governments. Focusing on the consequences of coalition governments characteristics in Israel between 2006 and 2015, this study shows how coalition behavior and structure impact the prime minister’s popularity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A long line of literature has called into question the reward/punish theory. For example, Achen & Bartels (2016) argued that citizens are not as omnipotent and sovereign as common democratic theories presume. Instead, citizens tend to base their decision-making on partisan loyalties.

In a competence-based voting (or popularity) approach, rational citizens observe the performance of the government and use optimally all the available information to infer administrative competence (Alesina et al., 1995, p.189). Here, however, competence is assumed to be directly observed by the public who is watching the behavior of the coalition government.

Before the September 11, 2001 attacks in the United States, the literature on popularity ratings of political leaders had rarely focused on terror as one of the main determinants that shape public opinion. Yet this does not mean that terrorism was absent from the study of popularity ratings during that period. A close review of the literature, especially in the United States, reveals that incidents of political violence, which can be described as an act of terror (or an attempt for such act) were often included with other politically salient incidents to capture “political drama” events (e.g., MacKuen, 1983; Ostrom & Simon, 1985; Ostrom & Smith, 1992) that the public is likely to pay attention to.

It should be noted that the focus here is not on the government’s ability to pass a specific policy. Instead, the theory suggests that even if virtually all proposed legislation by the government gets a majority in the parliament, the prime minister can still be held accountable when some coalition members oppose the bills.

When more than one survey result is available within the aggregated period, a weighted average is computed, which is weighted by the number of respondents in each survey. If no sample size is listed, it is assumed to be the average sample size of the polling firm.

The dependent variable is measured over a period of 114 months. In comparison to studies on popularity in other countries the number of observations is typical (e.g., Bellucci, 2006; Kelly, 2003; Treisman, 2011). It is important to note that early studies on popularity in a country tend to have a relatively low number of observations (e.g., Santagata, 1985; Bellucci, 2006), which later studies then expend with more data (e.g., Bellucci and De Angelis, 2013)

Similarly to the popularity data, the Stimson’s (1999) Dyad Ratios Algorithm is used to combine both into a single series.

According to the augmented Dickey-Fuller test the null hypothesis that the combined series follows a unit-root process cannot be rejected; and therefore, the series is transformed to its first-difference.

While it is possible to conceptualize terrorism and war as being part of the same ongoing conflict, we refer to two distinct manifestations of the conflict: military casualties during military operations and civilian casualties during terror events.

The data is available at: http://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/.

The time period of the study, from 2006 through 2015, means that all corruption related events were associated with Olmert. Corruption investigations involving Netanyahu started in December 2016, and are therefore not included in this study

We tested the correlation between the percentage of votes the prime minister participated in and the level of satisfaction over the years. The results show that there was very low correlation (-0.098) between the two series and therefore there is no evidence of a selection bias.

The data on legislative voting can be found in the Knesset website: http://www.knesset.gov.il

In a month when no vote takes place and the public has no new information on coalition cohesion, people are assumed to rely on information that was received in the previous month and therefore missing values are filled using previous month values.

The data is available at: http://www.parlgov.org/.

Replication files are available at the Harvard Dataverse site: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/RWFPHU

The coefficient of the variable measuring legislative cohesion within the prime minister’s party remains insignificant even when controlling for the size of the Prime Minister’s party.

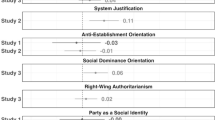

The impact of two other ideological indicators from the ParlGov database was also explored. Liberty-authority, which capture the religious dimension, and state-market that focuses on the economic dimension—measured on a 0-10 scale—were inserted in the models but failed to show statistically significant impact. In addition, combining all indicators into a single measurement also had no significant impact.

An important feature of the current model is that it includes factors beyond the lagged satisfaction level and economic performance. We conducted a Wald test of each type of component in the model- war/terror, fractionalization/cohesion, and political events - and found that each type of component makes an independent and significant contribution to the explanatory power of the model beyond that of the lag of satisfaction and the economy. We also conducted a dominance analysis that shows the following rank order of influence in the model: war, cohesion, negative personal events, negative domestic events, economy, terror, positive domestic events, negative international events, fractionalization, and positive international events. While the exact order is interesting, what is important is that there is evidence that a wide range of political factors (war, terror, events) and governmental structure have important explanatory roles.

Since approximately half of the cases in the time period of the study were coalition governments with less than 68 members, the variable takes a value of 1 when the coalition has at least 68 members, and zero otherwise.

References

Achen, C. H., & Bartels, L. M. (2016). Democracy for realists: Why elections do not produce responsive government. Princeton University Press

Alesina, A., Rosenthal, H., et al. (1995). Partisan politics, divided government, and the economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Amir, R., & Moshe, M. (2004). The construction of illusion: The ambivalence of Israeli public opinion about government. Israel Affairs, 10(4), 263–276.

Arce, M. E., & Carrión, J. F. (2010). Presidential support in a context of crisis and recovery in peru, 1985–2008. Journal of Politics in Latin America, 2(1), 31–51.

Arian, A., & Shamir, M. (2008). A decade later, the world had changed, the cleavage structure remained: Israel 1996–2006. Party Politics, 14(6), 685–705.

Arin, K. P., Ciferri, D., & Spagnolo, N. (2008). The price of terror: The effects of terrorism on stock market returns and volatility. Economics Letters, 101(3), 164–167.

Barber, J. D. (1966). Leadership strategies for legislative party cohesion. The Journal of Politics, 28(02), 347–367.

Bargsted, M. A., & Kedar, O. (2009). Coalition-targeted duvergerian voting: How expectations affect voter choice under proportional representation. American Journal of Political Science, 53(2), 307–323.

Baum, M. A., & Kernell, S. (2001). Economic class and popular support for franklin Roosevelt in war and peace. Public Opinion Quarterly, 65(2), 198–229.

Bellucci, P. (2006). All’origine della popolarità del governo in Italia, 1994–2006. Rivista italiana di scienza politica, 36(3), 479–504.

Bellucci, P., & De Angelis, A. (2013). Government approval in Italy: Political cycle, economic expectations and tv coverage. Electoral Studies, 32(3), 452–459.

Bellucci, P., & Lewis-Beck, M. S. (2011). A stable popularity function? Cross-national analysis. European Journal of Political Research, 50(2), 190–211.

Berlemann, M., & Enkelmann, S. (2014). The economic determinants of us presidential approval: A survey. European Journal of Political Economy, 36, 41–54.

Bosch, A., & Riba, C. (2005). Coyuntura económica y voto en españa, 1985-1996*. Papers: revista de sociologia, (75):117–140.

Burkhart, R. E., & Lewis-Beck, M. S. (1994). Comparative democracy: The economic development thesis. American Political Science Review, 88(04), 903–910.

Canes-Wrone, B., & De Marchi, S. (2002). Presidential approval and legislative success. Journal of Politics, 64(2), 491–509.

Carlin, R. E., Love, G. J., & Martínez-Gallardo, C. (2014). Security, clarity of responsibility, and presidential approval. Comparative Political Studies

Carlin, R. E., Love, G. J., & Martínez-Gallardo, C. (2015). Cushioning the fall: Scandals, economic conditions, and executive approval. Political Behavior, 37(1), 109–130.

Carlin, R. E., & Singh, S. P. (2015). Executive power and economic accountability. The Journal of Politics, 77(4), 1031–1044.

Chhibber, P., & Nooruddin, I. (2004). Do party systems count? The number of parties and government performance in the Indian states. Comparative Political Studies, 37(2), 152–187.

Christenson, D. P. & Kriner, D. L. (2016). Constitutional qualms or politics as usual? The factors shaping public support for unilateral action. American Journal of Political Science.

Christenson, D. P. & Kriner, D. L. (2017). Mobilizing the public against the president: Congress and the political costs of unilateral action. American Journal of Political Science.

Clarke, H. D., Stewart, M. C., Ault, M., & Elliott, E. (2005). Men, women and the dynamics of presidential approval. British Journal of Political Science, 35(01), 31–51.

Clarke, H. D., Stewart, M. C., & Zuk, G. (1986). Politics, economics and party popularity in Britain, 1979–83. Electoral Studies, 5(2), 123–141.

Conley, R. S. (2006). From elysian fields to the guillotine? The dynamics of presidential and prime ministerial approval in fifth republic France. Comparative Political Studies, 39(5), 570–598.

Dalton, R. J. (2008). The quantity and the quality of party systems party system polarization, its measurement, and its consequences. Comparative Political Studies, 41(7), 899–920.

Döring, H., & Manow, P. (2010). Parliament and government composition database (parlgov). An infrastructure for empirical information on parties, elections and governments in modern democracies. Version, 10(11):6.

Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of political action in a democracy. The Journal of Political Economy, pp. 135–150.

Druckman, J. N. (1996). Party factionalism and cabinet durability. Party Politics, 2(3), 397–407.

Druckman, J. N., & Holmes, J. W. (2004). Does presidential rhetoric matter? Priming and presidential approval. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 34(4), 755–778.

Duch, R. M., & Stevenson, R. T. (2008). The economic vote: How political and economic institutions condition election results. Cambridge University Press.

Eichenberg, R. C., Stoll, R. J., & Lebo, M. (2006). War president: The approval ratings of George W. Bush. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 50(6), 783–808.

Freeman, J. R., Williams, J. T., & Lin, T.-M. (1989). Vector autoregression and the study of politics. American Journal of Political Science, pp. 842–877.

Gelpi, C., Peter, D. F., & Reifler, J. (2005). Success matters: Casualty sensitivity and the war in Iraq. International Security, 30(3), 7–46.

George, A. L. (1980). Domestic constraints on regime change in us foreign policy: The need for policy legitimacy. Change in the International System, pp. 233–262.

Gronke, P., & Newman, B. (2003). Fdr to clinton, mueller to?: A field essay on presidential approval. Political Research Quarterly, 56(4), 501–512.

Hadar, Y. (2009). Israeli public’s trust in governing institutions over the past decade. Parliament, 63

Heper, M., & Shifrinson, J. (2005). Civil-military relations in Israel and Turkey. Journal of Political and Military Sociology, 33(2), 231–248.

Hetherington, M. J., & Nelson, M. (2003). Anatomy of a rally effect: George W. Bush and the war on terrorism. Political Science and Politics, 36(01), 37–42.

Hibbs, D. A., & Vasilatos, N. (1981). Economics and politics in France: Economic performance and mass political support for presidents Pompidou and Giscard D’estaing*. European Journal of Political Research, 9(2), 133–145.

Hix, S., & Noury, A. (2016). Government-opposition or left-right? The institutional determinants of voting in legislatures. Political Science Research and Methods, 4(02), 249–273.

Hix, S., Noury, A., & Roland, G. (2005). Power to the parties: Cohesion and competition in the European Parliament, 1979–2001. British Journal of Political Science, 35(02), 209–234.

Hobolt, S., Tilley, J., & Banducci, S. (2013). Clarity of responsibility: How government cohesion conditions performance voting. European Journal of Political Research, 52(2), 164–187.

Iyengar, S., & Kinder, D. R. (1987). News that matters: Agenda setting and priming in a television age. News that Matters: Agenda-Setting and Priming in a Television Age.

Kaarbo, J., & Beasley, R. K. (2008). Taking it to the extreme: The effect of coalition cabinets on foreign policy. Foreign Policy Analysis, 4(1), 67–81.

Kelly, J. M. (2003). Counting on the past or investing in the future? Economic and political accountability in fujimori’s peru. The Journal of Politics, 65(3), 864–880.

Klingemann, H. (2005). Political parties and party systems. In J. Thomassen (Ed.), The European voter: A comparative study of modern democracies (pp. 22–63). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Krosnick, J. A., & Brannon, L. A. (1993). The impact of the gulf war on the ingredients of presidential evaluations: Multidimensional effects of political involvement. American Political Science Review, 87(04), 963–975.

Krosnick, J. A., & Kinder, D. R. (1990). Altering the foundations of support for the president through priming. American Political Science Review, 84(02), 497–512.

Laakso, M., & Taagepera, R. (1979). The" effective" number of parties:" A measure with application to west Europe". Comparative Political Studies, 12(1), 3.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Stegmaier, M. (2013). The vp-function revisited: A survey of the literature on vote and popularity functions after over 40 years. Public Choice, 157(3–4), 367–385.

Lijphart, A. (2012). Patterns of democracy: Government forms and performance in thirty-six countries. Yale University Press.

Lupia, A., & Strøm, K. (1995). Coalition termination and the strategic timing of parliamentary elections. American Political Science Review, 89(03), 648–665.

MacKuen, M. B. (1983). Political drama, economic conditions, and the dynamics of presidential popularity. American Journal of Political Science, pp. 165–192.

MacKuen, M. B., Erikson, R. S., & Stimson, J. A. (1992). Peasants or bankers? The American electorate and the US economy. American Political Science Review, 86(03), 597–611.

Miller, J. M., & Krosnick, J. A. (2000). News media impact on the ingredients of presidential evaluations: Politically knowledgeable citizens are guided by a trusted source. American Journal of Political Science, 301–315.

Mualem, M. (2007). "Olmert: I Know I’m Unpopular, but I’m Here to Work". Retrieved November 16, 2018 from http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/news/olmert-i-know-i-m-unpopular-but-i-m-here-to-work-1.215762.

Mualem, M. (2009). War and election - winning combination. Retrieved November 16, 2018 from http://news.walla.co.il/item/1410847.

Mueller, J. E. (1970). Presidential popularity from Truman to Johnson. American Political Science Review, 64(01), 18–34.

Mueller, J. E. (1973). War, presidents, and public opinion. Wiley.

Nadeau, R., Niemi, R. G., Fan, D. P., & Amato, T. (1999). Elite economic forecasts, economic news, mass economic judgments, and presidential approval. The Journal of Politics, 61(01), 109–135.

Nadeau, R., Niemi, R. G., & Yoshinaka, A. (2002). A cross-national analysis of economic voting: Taking account of the political context across time and nations. Electoral Studies, 21(3), 403–423.

Neustadt, R. E. (1980). Presidential power: The politics of leadership from FDR to Carter. Wiley

Newman, B. (2002). Bill clinton’s approval ratings: The more things change, the more they stay the same. Political Research Quarterly, 55(4), 781–804.

Newman, B., & Forcehimes, A. (2010). “Rally round the flag’’ events for presidential approval research. Electoral Studies, 29(1), 144–154.

Nicholson, S. P., Segura, G. M., & Woods, N. D. (2002). Presidential approval and the mixed blessing of divided government. Journal of Politics, 64(3), 701–720.

Norpoth, H. (1996). Presidents and the prospective voter. The Journal of Politics, 58(03), 776–792.

Ostrom, C. W., & Simon, D. M. (1985). Promise and performance: A dynamic model of presidential popularity. American Political Science Review, 79(02), 334–358.

Ostrom, C. W., & Smith, R. M. (1992). Error correction, attitude persistence, and executive rewards and punishments: A behavioral theory of presidential approval. Political Analysis, 127–183.

Ostrom, C. W., Jr., Kraitzman, A. P., Newman, B., & Abramson, P. R. (2018). Polls and elections: Terror, war, and the economy in George W. Bush’s approval ratings: The importance of salience in presidential approval. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 48(2), 318–341.

Ostrom, C. W., Jr., & Simon, D. M. (1989). The man in the Teflon suit? the environmental connection, political drama, and popular support in the Reagan presidency. Public Opinion Quarterly, 53(3), 353–387.

Phillips, P. C., & Perron, P. (1988). Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika, 75(2), 335–346.

Pickup, M. (2010). Better know your dependent variable: A multination analysis of government support measures in economic popularity models. British Journal of Political Science, 40(02), 449–468.

Powell, J. G. B., & Whitten, G. D. (1993). A cross-national analysis of economic voting: Taking account of the political context. American Journal of Political Science, 391–414.

Rae, D. W. (1967). The political consequences of electoral laws. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Rahat, G. (2007). Determinants of party cohesion: Evidence from the case of the Israeli parliament. Parliamentary Affairs, 60(2), 279–296.

Reeves, A., & Rogowski, J. C. (2016). Unilateral powers, public opinion, and the presidency. The Journal of Politics, 78(1), 137–151.

Reiter, D., & Tillman, E. R. (2002). Public, legislative, and executive constraints on the democratic initiation of conflict. Journal of Politics, 64(3), 810–826.

Robinson, P. (1995). Log-periodogram regression of time series with long range dependence. The Annals of Statistics, 23(3), 1048–1072.

Rudolph, T. J. (2002). The economic sources of congressional approval. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 27(04), 577–599.

Santagata, W. (1985). The demand side of politico-economic models and politicians’ beliefs: The Italian case. European Journal of Political Research, 13(2), 121–134.

Sapir, E. (2007). Sympathy level for incumbent prime ministers 1984-2006. Retrieved 21 Jan, 2016 from http://en.idi.org.il/projects/the-guttman-center-for-surveys/.

Schermann, K., & Ennser-Jedenastik, L. (2014). Coalition policy-making under constraints: Examining the role of preferences and institutions. West European Politics, 37(3), 564–583.

Shamir, M. (2015). The Elections in Israel 2013 (Vol. 1). Transaction Publishers.

Sheafer, T. (2007). How to evaluate it: The role of story-evaluative tone in agenda setting and priming. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 21–39.

Sheafer, T. (2008). The media and economic voting in Israel. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 20(1), 33–51.

Sigelman, L., & Yough, S. N. (1978). Left-right polarization in national party systems: “A cross-national analysis’’. Comparative Political Studies, 11(3), 355.

Sims, C. A. (1980). Macroeconomics and reality. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, pp. 1–48.

Smoke, R. (1994). On the importance of policy legitimacy. Political Psychology, 97–110.

Stegmaier, M., Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Park, B. (2017). The vp-function: A review. The SAGE Handbook of Electoral Behaviour, 2, 584–605.

Stimson, J. A. (1999). Public Opinion in America: Moods, Cycles, and Swings, 2nd edn. Westview Press.

Tir, J., & Singh, S. P. (2013). Is it the economy or foreign policy, stupid? The impact of foreign crises on leader support. Comparative Politics, 46(1), 83–101.

Treisman, D. (2011). Presidential popularity in a hybrid regime: Russia under Yeltsin and Putin. American Journal of Political Science, 55(3), 590–609.

Tsfati, Y., Sheafer, T., & Weimann, G. (2009). War on the agenda: The Gaza conflict and communication in the 2009 elections. The Elections in Israel, 225–250.

Volkerink, B., & De Haan, J. (2001). Fragmented government effects on fiscal policy: New evidence. Public Choice, 109(3–4), 221–242.

Wang, C.-H. (2014). The effects of party fractionalization and party polarization on democracy. Party Politics, 20(5), 687–699.

Whitten, G. D., & Palmer, H. D. (1999). Cross-national analyses of economic voting. Electoral Studies, 18(1), 49–67.

Willer, R. (2004). The effects of government-issued terror warnings on presidential approval ratings. Current Research in Social Psychology, 10(1), 1–12.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendices

See Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kraitzman, A.P., Ostrom, C.W. The Impact of Governmental Characteristics on Prime Ministers’ Popularity Ratings: Evidence from Israel. Polit Behav 45, 1143–1168 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09752-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09752-4