Abstract

To examine whether political orientation is reflected in actual behavior, we applied classical paradigms of behavioral economics, namely the Public-Goods- (PGG) and the Trust-Game (TG) which constitute measures of cooperativeness, interpersonal trust and reciprocity respectively in a large German sample of N = 454. Participants intending to vote for right-of-center-parties showed significantly lower monetary transfers in both games than those intending to vote for left-of-center-parties. Accordingly, both scores were negatively associated with self-assessed conservatism and support for policies advocated by Germany’s right-of-center-parties, while showing positive correlations with the support of policies left-of-center-parties advocate. Interestingly, both measures also show distinct correlational patterns with Right-Wing-Authoritarianism and Social-Dominance-Orientation. None of these patterns applied to the Lottery-Game measuring unspecific risk-tolerance. We conclude by discussing potential psychological mechanisms mediating the relationships between ideology and actual social behavior as well as differences in experimental design to explain the deviant pattern of (null-) results in former studies relating ideology to behavior in game-theoretic paradigms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although psychology is a behavioral science, in the field of political psychology, studies investigating the relationship between political orientation and actual social behavior are relatively scarce unless overtly political behavior is concerned (e.g. voting, protesting, petitions etc.) or social behavior is defined very widely to encompass for example reactions to threatening stimuli. This imbalance recently led Jost (2017) to point to the question whether ideological differences could be confined to self-report-measures and therefore of little relevance to actual behavior. This would represent one of the most pertinent criticisms in political psychology. A promising approach would be the use of well-validated paradigms informed by game-theory, representing controlled situations in which behavioral decisions directly impact participant`s (monetary) outcomes (Fehr and Schmidt 1999). Regarding their general structure, these games may be seen as variations of the classical and well-known Prisoner’s Dilemma (PD), because consistently a social dilemma is constructed mainly by preventing communication among the players: The common benefit of players can be maximized by cooperative behavior, while the individual decision of one player is made under uncertainty about how the other(s) will react (Deutsch 1949, 1958). In contrast to the classical PD, in more modern paradigms as the Trust- (TG) or Public-Goods-Game (PGG), chances and risks are not distributed equally among the players. Instead, the decisional dilemma concentrates on one party (see Methods). These paradigms could be shown to produce internally and ecologically valid estimates of behavioral dispositions as Trust, Reciprocity and Cooperativeness (Brülhart and Usunier 2012; Englmaier and Gebhardt 2016; Kosfeld et al. 2005). Apart from the field of political psychology, research using those paradigms is rich and has led to diverse valuable insights regarding for example the development of trust, reciprocity and cooperation (Fehr and Schmidt 1999), potential biological influences on trust-behavior, with a strong focus on the Oxytocin-System (Baumgartner et al. 2008; De Dreu et al. 2010; Kosfeld et al. 2005; Lane et al. 2013; Mikolajczak et al. 2010; Zak et al. 2007; for a critical discussion based on heterogenous findings see Nave et al. 2015) or the influence of personality traits as Machiavellianism on decision-making (Gunnthorsdottir et al. 2002). Brocklebank et al. (2011) showed, that a game-derived factor of prosocial orientation is predicted by openness, emotional stability and low extraversion and Lönnqvist et al. (2011) showed similar correlations between these traits and the transferred amount in a Trust-Game.

Surprisingly, the few existing studies relating ideological differences to behavior in such “economic” paradigms yielded null-results for the most part: Fehr et al. (2003) reported greater behavioral indices of trust among proponents of Germany’s largest parties but no association with ideology per se. Balliet et al. (2016) let participants play a reduced form of the Trust-Game with partners who were identified as republican or democrat. No general association of the transferred amount with ideology were found, instead participants merely showed ingroup-favoritism by transferring more to partners that shared their self-description as republican vs. democrat. The authors could also show that this effect was mediated by the expected cooperation of ingroup- vs. outgroup-members. Alford and Hibbing (2007) confronted participants with one of two somewhat unspecified games: In the first game, participants could choose an amount of money between 0 and 10$ to withdraw from a common pool of funds (unfortunately, it is unclear, whether the participants were given information about how this pool was composed). The second game was described as an Ultimatum Game. Here, participants are to decide which fraction of their initial endowment they want to transfer to another player who has the chance to reject the first player`s offer. If the offer is rejected, both players do not receive any money (Civai and Hawes 2016). Alford and Hibbing (2007) report non-significant associations of both game outcomes with ideological self-placement and the Wilson-Patterson-C-Scale, which taps conservatism via one’s approval of conservative policies. Most relevant to the present study, Anderson et al. (2004) did not find differences between participants with democratic vs. republican leanings and between liberal vs. conservative participants in averaged transfers in thirty rounds of the Public-Goods- and the Trust-Game. Noteworthy, the same eight players interacted with each other throughout the experiment. Null-results even emerged, when inequity was induced by altering the show-up-fees.

These null findings are surprising in light of a wealth of theoretical and empirical work proposing fundamental differences between conservatives and liberals related to the management of uncertainty and threat (Hibbing et al. 2014; Jost 2017; Jost et al. 2003). In fact, even leaving aside causal explanation models, the mere description of the core-elements of (conservative) ideology as resistance to change and acceptance of inequality (Jost et al. 2003) would suggest differences in game-paradigms, which are inherently characterized by uncertainty of the other player’s decision and differential outcomes. Accordingly, it is hard to think of only one theoretical account which would predict null-differences, whether these accounts focus on differences in personality, epistemic or existential needs, general regulatory focus or system-justifying and hierarchy-enhancing tendencies (see Jost et al. 2003 for a review). Also, acknowledging the role of politics as regulating social processes in the large scale (Alford and Hibbing 2007), it is hard to explain, why differences should emerge in nonsocial contexts as simple perceptual paradigms or individual learning tasks, but not in inherently social game-situations. Evidence for the former is ample, diverse and rapidly growing: Dodd et al. (2012) found faster fixation and longer viewing of negative as opposed to positive IAPS-pictures, including pictures with no obviously social content (e.g. a sunset or vomit), among conservatives. Oxley et al. (2008) reported increased skin-conductance-reactivity in response to threatening pictures and a stronger physiological startle reflex in response to white-noise-bursts among participants holding conservative views. Shook and Fazio (2009) found liberals to be more explorative when it comes to discriminate good from bad beans in a reward-associated computer-task. Amodio et al. (2007) found a positive association of self-reported liberalism with behavioral accuracy in No-Go-Trials of a Go-/No-Go-task, i.e. a greater ability to withhold habituated responses, and with conflict-related EEG-measures. In MRT-research, no task at all—let alone a task with social content—seems to be necessary to show differences between conservatives and liberals: Kanai et al. (2011) showed positive relationships between the volume of the anterior cingulate, which is involved in conflict-monitoring, and liberalism as well as a positive relationship between conservatism and the volume of the right amygdala, which is predominantly associated with fear and anxiety (LeDoux 2003). However, facing failed attempts to replicate some of the most prominent of the mentioned findings, it is imperative to mention the perspective of Bakker et al. (2019), who urge the field not to take unconscious reactions as the most real or valid indicators of "real" ideological predispositions as some bold statements in the mentioned papers may suggest. There probably is no hardwired, unmediated connection between unconscious reactions and (political) decisionmaking, but unconscious reactions may represent only one input to a complex system, which is consciously or even unconsciously malleable (Butler et al. 2014; LeDoux and Pine 2016). Therefore, in political psychology, an exclusive focus on the most basic and unconscious psychological or even physiological functions or anatomical phenotypes should be avoided. Investigating the associations between political orientation and more integrated phenomena (as behavior in specific games) on the other hand, appears to be a potentially fruitful line of research.

The pertinent question remains why ideological differences seem to not extend to game outcomes, i.e. why a more conservative ideology should not predispose for less trusting, more selfish and cautious or less reciprocal and cooperative behavior, as conservative’s possibly greater negativity bias (see Hibbing et al. 2014), their prevention-based regulatory focus (Higgins 1998; Janoff-Bulman 2009), their need for cognitive closure (Webster and Kruglanski 1994) or their general personality-structure (Altemeyer 1981; Pratto et al. 1994) would suggest. Today, we are aware of only two studies being successful in linking economic outcomes to political ideology: Van Lange et al. (2012) identified three types of different social value orientations among their participants by the so-called triple-dominance-decomposed-game. Herein, participants are presented nine items whose three answer-options represent different ways of allocating points to oneself and an unknown other. The individual choice can be individualistic (largest personal outcome), prosocial (largest joint outcome) or competitive (maximal difference between own and other’s outcome). Participants were classified when they made six decisions that were consistent with one of these orientations. The authors showed in three independent Italian and Netherlandish samples, that competitors and individualists showed stronger conservative preferences and were more likely to vote for right-of-center parties than prosocials were. Using the very same methods, Chirumbolo et al. (2016) replicated the finding of a positive correlation between an individualistic social value orientation and a conservative political orientation in an Italian sample. It is not conceivable why ideological differences emerge in this game but not in related, equally well validated paradigms as the PGG or the TG. We suggest, that the crucial difference lies in the blatant information about the opponent player in the studies revealing null-results that could be capable of overriding the expectedly small effects of ideology and that was carefully prevented by Van Lange et al. (2012) and Chirumbolo et al. (2016). Evidence showing that characteristics of other players influence behavior in game paradigms is ample: In fact, already the very first study using the TG showed that information about the course of the game in an independent sample influences participants behavior (Berg et al. 1995). More to the point, information about one’s specific opponent or on his or her prior behavior, influences behavior massively: DeBruine (2002) showed facial resemblance of the participant and the opponent to increase trustful behavior in the TG. Breaches of trust (i.e. player 2 not transferring back a fair share to player 1, see methods) led participants to adapt their behavior in subsequent rounds (Baumgartner et al. 2008). Krueger et al. (2007) showed altered patterns of brain-activation, especially in the paracingular cortex, when participants had experienced a breach of trust by their opponent. Delgado et al. (2005) demonstrated biographic information about the opponent to influence investment-decisions and activation of the caudate nucleus and Mikolajczak et al. (2010) showed that information about the opponent’s academic profession and his hobbies do have an impact on transfers in the TG. National and racial differences between partners predict tendencies to cheat each other, while hints to one’s family status, social skills and charisma are positively associated with outcomes in the TG (Glaeser et al. 2000). So, we assume that hints to the other players’ trustworthiness, indicators of similarity or disparity or information about their past behavior has covered ideological differences in trust and cooperativity in the studies mentioned above. We hypothesized that significant differences between right- and left-leaning participants in the TG and the PGG do emerge when such information is not available and we assume that these differences do reflect real differences in dispositional trust, reciprocity and cooperativity. Accordingly, we did not expect differences to extend to the Lottery-Game (LG), measuring unspecific risk tolerance as a potential confound.

Generally, the often exclusive use of direct self-reports as measures of political orientation seems to be problematic. They implicitly assume a consistent comprehension of the labels “conservative” and “liberal” or “left” and “right” in the public, which may be contradicted when terms as Neoliberalism become more and more common. Also, the labels per se may mean different things to different age-cohorts etc. (Anderson et al. 2004). On the other hand, most people are willing and able to give self-placements in these terms (Jost 2006). Alternative, contentual measures as the Wilson-Patterson-C-Scale (Wilson and Patterson 1968) do have the problem of low generalizability—locally and temporally. Items asking for the individual position on death-penalty for example, will reasonably lead to floor-effects in Germany as its reintroduction is not advocated by any important party. Most crucially, these instruments are purpose-built to yield estimates of conservatism by asking for one’s stances on prototypic issues as death penalty or school uniforms which may give rise to tautological reasoning. We mean by this that the use of purpose-built instruments may lead to the investigation of personality’s influence on what psychologists define as conservative at a given point in time and under the impression of a certain country’s political history and may therefore replace the varying individual conceptions of certain labels in self-placements by a universal, inflexible and not necessarily more valid one. To us, a combination of self-ratings with a measure of the participant’s stances on timely and relevant policy-issues, being consistently updated, seems to be the best way to measure political orientation. In Germany, such a measure is available as the “Wahl-O-Mat” (WoM) of the federal agency for political education (see Methods).

So, we tried to show the behavioral significance of political orientation—conceptualized in both ways; by self-reports of one’s position on an ideological dimension, of actual voting intention and of voting behavior and by WoM—by testing for relationships with behavioral indicators of Trust, Reciprocity and Cooperativeness. With respect to the broadness of both constructs, ideology has been compared to personality before (Alford and Hibbing 2007). Therefore, we decided to employ a standard measure of the Big Five Personality traits additionally to be able to assess the incremental explanatory power of ideology beyond personality for behavioral outcomes. While personality traits have repeatedly been shown to influence behavior in game-paradigms (e.g. Lönnqvist et al. 2011; Czibor and Bereczkei 2012; Gunnthorsdottir et al. 2002), we hypothesized that political orientation may be of similar explanatory power and may even increase explained variance.

Material and Methods

Participants

Our sample consisted of N = 454 participants. Age ranged from 17 to 75 years (M = 26.26; SD = 8.70). Educational levels were fairly high. Asked for their highest educational achievement, 52.4% stated a general qualification for university entrance (German "Abitur"), 30.4% had graduated from university, 4% achieved the vocational baccalaureate ("Fachabitur"), 3.5% acquired the intermediate school-leaving certificate ("mittlere Reife") and 0.7% the basic school qualification ("Hauptschulabschluss"). 5.5% preferred not to answer the question for educational achievement. The first wave of participants (n = 82) was tested in our laboratory. To enlarge our sample and to avoid the restriction on undergraduates, we decided to fully computerize our study and to make it accessible online afterwards. However, the notably skewed gender distribution (39% male), high educational levels and the rather low mean age are presumably due to the overrepresentation of psychology students (the vast majority of psychology students in Germany is female) who received additional course-credit for participation. All participants got their monetary credit of one randomly chosen game (see below) in real money for compensation.

Questionnaires and Wahl-O-Mat

NEO-FFI

We administered the NEO-Five-Factor-Inventory (NEO-FFI, Costa and McCrae 1992) in its German translation (Borkenau and Ostendorf 1993) to assess the Big Five as a benchmark for predictive value concerning game-derived outcomes. Further information on the instrument can be found in Borkenau and Ostendorf (2008).

RWA and SDO

The theories of Right-Wing-Authoritarianism (RWA; Altemeyer 1981) and Social Dominance Orientation (SDO; Pratto et al. 1994) both are partially grounded in the Authoritarian Personality Theory (Adorno et al. 1950). To assess both dimensions, scales were developed which were meant to overcome the various flaws in Adornos original F-Scale, meant to assess the authoritarian personality. In developing a scale for RWA, Altemeyer (1981) focused on only three of the originally nine clusters of the F-Scale to reach one-dimensionality: Authoritarian conventionalism, authoritarian submission and authoritarian aggression. People scoring high on RWA thus can be characterized as sticking to the tried and true, being obedient and submissive to authorities and being aggressive towards elements of society which represent threats to or question the established order and conventions. Generally, the scale shows high measures of internal consistency (for estimates of internal consistency in our sample see Table 1).

SDO on the other hand, refers to people’s general orientation towards intergroup relationships, more specifically to the question, whether one prefers these relationships to be more hierarchical or more equal. Originally developed more than ten years after the RWA-Scale, the SDO-Scale seems to tap different clusters of Adornos original theory, especially the need for maintenance of power, destructivity, cynicism and anti-intraception (Duckitt and Sibley 2010; Adorno et al. 1950). People scoring high on SDO may thus be characterized as depreciating and showing a general hostility to others (Adorno et al. 1950).

Up to now, there are different answers to the question whether RWA and SDO may be seen as dimensions of personality or as measures of attitudes. In contrast to most established personality inventories, the items of both scales do not predominantly ask for behavioral tendencies but for social attitudes and personal beliefs. On the other hand, both scores show high temporal and situational stability (Pratto et al. 1994). However, intraindividual changes in both scores in response to differing situations, priming or changes in one’s own societal position have been reported (Duckitt and Fisher 2003; Guimond et al. 2003). Being unchangeable of course would be a hard criterion for measures of personality as various findings prove intraindividual variability in established measures of the Big Five in response to aging or critical life events for example (Boyce et al. 2015; Specht et al. 2011). Presumably, most scholars would agree, that intraindividual variability in total scores does not necessarily speak against stable traits, as long as interindividual differences in these dimensions retain across differing situations. In light of their finding, that both scores show higher correlations with measures of attitudes and values than with established measures of the Big Five (Sibley and Duckitt 2008), Duckitt and Sibley (2010) propose RWA and SDO to be persistent motivational goals, made chronically salient to the person by certain worldviews which are in turn shaped by core-personality-traits and socio-structural factors. Here, we adopt this definition. Seen in this light, RWA and SDO directly tap the stable motivational basis for the two core-aspects of political orientation mentioned above: Resistance to change should be motivated by RWA, acceptance of inequality by SDO.

Here, RWA was assessed using a shortened form, the “balanced short scale of authoritarian attitudes” (B-RWA-6), which has been developed for and actually used in the Austrian National Election Study (Aichholzer and Zeglovits 2015). Here, each of the subscales mentioned above is assessed by two items, one of which is poled reversely. Several findings prove the scales reliability and validity and are accessible via the collection of items and scales for the social sciences (ZIS; www.zis.org). Participants had to indicate their support for the six statements on a Likert-Scale with five stages.

SDO was assessed by a German adaptation of the SDO-Scale (Pratto et al. 1994). The items were translated by a professional interpreter and retranslated by the first author. After comparing retranslations and original items, little modifications were done to the original translation. As the B-RWA-6, the SDO-Scale is balanced, meaning that eight of the 16 Items were reversely poled, thus asking for the preference of equality. Participants had to indicate their support for the 16 statements on a Likert-Scale with seven stages.

Wahl-O-Mat 2013

The “Wahl-O-Mat” (WoM) is a web-based tool offered by the federal agency for political education in Germany. Originally constructed in 2002, it is consistently updated prior to elections on the state, federal or European level. Originally intended to provide information for young people voting for the first time, it has been widely accepted in Germany and has been used more than 50 Million times in total prior to elections. The instrument nowadays consists of 38 statements, chosen and formulated by an invited council, which are answered by the German parties. The whole construction process is supervised by political scientists. The parties as well as the participants can rate their support for the statements by clicking “agree”, “disagree” or “neutral”. Also, participants have the opportunity to skip certain statements and to indicate which statements are especially important to them. The answers to those will be double-weighted. The actual statements can be described as concrete policy-positions. For example, prior to the federal election in 2013, participants could rate their support for statements as “In Germany, a legal minimum wage should be introduced” or “Video surveillance should be expanded in public space”. The answers of the participant and the several German parties are then compared by an algorithm, resulting in a percentage of accordance. In essence, for each of the 38 statements, the participant is given two points, if his stance on the respective statement is the same as the respective party's one. If it is near—e.g. the participant stating "neutral" and the party stating "agree" or "disagree"—he is given one point. If it is opposite—i.e. the participant states "agree" and the party "disagree" or vice versa, he is given zero points. If the participant marks one statement as especially important, points are doubled; if he chooses to skip a statement, it will be excluded from calculations. Finally, the points of the participant are divided by the highest possible number of points (given the participant's skips and weightings) and multiplied by 100. The same procedure is repeated for every party. We replicated the original algorithm but restricted it to the most important political parties in Germany, which are the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), a party usually ascribed to right-wing-populism, the Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP), a party known for its economic liberalism, the Christlich-Demokratische/Christlich-Soziale-Union (CDU/CSU), the traditional conservative party of chancellor Angela Merkel, the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD), Germany’s social democratic party, Die Gruenen, a party explicitly pronouncing the need for protection of the environment and Die Linke, a party confessing to the aim of a democratic socialism (bpb 2013). According to data of one of Germany’s most renowned polling agencies “infratest dimap” based on a representative survey, the order of this list represents public ratings concerning the location of the parties on a right-left continuum (infratest dimap 2015). To improve readability, we will supplement the names of the parties with “ + ” and “−” indicators throughout this manuscript, indicating a right- vs. left-leaning orientation respectively. So, we gained six scores of percentual accordance (one for each of the mentioned parties) per participant. Additionally, we used the data of Infratest dimap (2015) to create a WoM composite score. Here, the six individual scores were weighted by the distance of the respective party to the political center as identified by Infratest dimap (2015) before they were averaged. As the scores for parties right of center were positively and those for parties left of center were negatively weighted, higher scores of this WoM_com variable indicate higher agreement with conservative stances. A complete list of WoM-items is given in the Online Appendix (A1) and a SPSS syntax file for automated analysis may be requested from the authors at any time. For clarification, we used the specific version of the Wahl-O-Mat, that was created prior to the federal election in 2013. We did so for two reasons in particular: First and foremost, the most actual version of the WoM—the one created with respect to the federal election in 2017—was not available at the beginning of data collection. Second, one could argue, that differences especially between the two biggest parties (CDU+ and SPD−) were much more pronounced during their campaigns in 2013 than they are now (after more than four years of common government). In light of the current political climate one could argue, that these positions more truly represented the actual orientation of the parties. For example, Merkel recently allowed the parliament to freely ballot about the right of homosexuals to marry. Although she, in line with most of her party, explicitly voted against that right, it was finally introduced. This removed the ever controversial issue from the most modern WoM, disguising the fact, that CDU+ and SPD− still have different stances about this topic. The same could be said about the legal minimum wage as another important issue. The WoM 2013 has been used 13.300.000 times prior to the election in 2013, proving its acceptance in German society. To avoid expectancy-effects, we did not initially inform our participants, that they were answering the WoM. Instead it was presented as a measure of “societal attitudes” to them.

Self-placements

As most studies cited above, we asked the participants for self-ratings of their political orientation. Specifically, we used four items, the first of which referred to “politics in general”. On a subsequent page, participants were asked for self-placements “with regard to social policies” and “with regard to economic policies”. For these three items a seven-point Likert-scale, ranging from “very conservative” to “very liberal” was used. We chose to use four instead of only one general item, to be able to detect misconceptions of the terms “liberal” and “conservative” which could be caused by the pervasiveness of terms as “neoliberalism” and—especially in Germany—by the self-description of the FDP++ as “the Liberals”, both referring to the denial of regulations in the economic realm for the most part. These positions paradoxically should be coined “conservative” according to the definitions given above. Additionally, participants were asked to indicate their political orientation on a seven-point Likert-scale ranging from “right” to “left”. Lastly, participants were asked to indicate which party they voted for in the actual federal election in 2013 and which party they would vote for if the next federal election was held next Sunday (voting-intention; here, we explicitly asked for the second vote only, which in Germany is critical for the number of seats in the parliament).

Games

Public-Goods-Game

Generally, the Public-Goods-Game (PGG) can be described as a n-person Prisoner’s Dilemma (with n > 2), where every player has to decide which amount of his initial endowment he wants to invest into a public pool. Critically, contributions to the public pool are multiplied and—at the end of a round—shared equally among all players, including those who chose to free-ride or to invest little into the public good (Civai and Hawes 2016). Since the multiplication-factor is lower than the number of players, a dilemma arises: First, this arrangement leads to a marginal per capita return (MPCR) of less than one. This means, that—for one monetary unit invested into the public good—the investor personally only receives a fraction of one back: MPCR < 1. Second, the group of all players as a whole (n) profits from higher investments into the public good, because the product of n and MPCR is larger than one: MPCR < 1 < n*MPCR (Chaudhuri 2011). As any investment in the public good subtracts from the outcome of any individual player, their dominant strategy is to invest nothing, leading to an equilibrium solution of nobody contributing to the public good. But in fact, people consistently invest amounts larger than zero. The interindividual variability in investment mirrors variability of cooperative behavior outside of the laboratory, as Englmaier and Gebhardt (2016) could show, making the PGG a valid measure of cooperativeness. In addition, experimental games generally reach high estimates of reliability (cf. Fehr et al. 2003).

Trust Game

In the Trust Game (TG, Berg et al. 1995) only two players are involved, one of which is ascribed to the role of the Investor, the other one acts as the Trustee. Both players are equipped with the same initial endowment. In the first move, the Investor has to decide, how much of his endowment he invests, i.e. how much he transfers to the Trustee. Critically, the Investor’s transfer is tripled, so that the Trustee receives the tripled investment of the Investor on top of his own initial endowment. In the second move, the Trustee decides, how much is sent back to the investor. The Trust-Game is widely used to operate Trust, indicated by the first move, and Reciprocity, indicated by the second move. Divergent from the PGG, both players could individually profit from higher investments. Nonetheless, in a one-shot-game, keeping all represents the sub-game perfect equilibrium for the Trustee. Therefore, the best response for the Investor would be to give nothing. In fact, participants usually clearly deviate from this equilibrium-solution: Investors show a high level of Trust and Trustees usually send back one third of their total deposit (Civai and Hawes 2016; Cochard et al. 2004).

Lottery Game

In addition to PGG and TG, we used the so called Lottery-Game (LG) to make sure, that PGG and TG indeed yield indices for Cooperativeness, Trust and Reciprocity instead of a measure of unspecific risk-tolerance. In the LG, an array of binary choice-scenarios is presented to the participant: The participant has to choose between a safe payment and a lottery. In any situation, the lottery-option is the same: If it is chosen, the participant with a chance of 50% wins the maximal amount available and with a chance of 50% he wins nothing. By contrast, the safe payment option changes across the situations, it’s value rises gradually. The Von-Neumann-Morgenstern utility function suggests, that the frequency of decisions for both options becomes equal when the stochastic expectancy value is the same for both options (Von Neumann and Morgenstern 2007). Deviations from this pattern therefore can be interpreted as relative risk-aversion or –affinity, operationalized by the marginal value at which the participant opts for the safe payment for the first time.

For our study, all games were fully computerized. The participants did not play live with others, but were sincerely informed, that—after data-collection was completed—they would be randomly assigned to other participants, whose decisions actually would impact their own monetary outcome. PGG and TG were played in a one-shot manner. The participants got extensive instructions on both games and had to do two practice-tasks before the respective game actually started. Here, decisions of exemplary players were presented and the participant had to calculate the outcomes of those to make sure, that they understood the game-structure. In our actual version of the TG, participants were informed, that their initial endowment was 2.00€. In the first move, they had to indicate, which amount (from 0.00€ to 2.00€ in steps of 0.20€) they want to send to the unknown trustee (who would be another randomly chosen participant). In the second move, every possible offer of the yet-to-be-determined first player was presented to the participant. For each possibility (X) the participant had to answer the question “If Player 1 transfers X to me (my own endowment would be Y), I would send Z (from 0.00 to the participant’s actual endowment in steps of 0.20€) back to him”. In our version of the PGG, participants were informed, that there were four more yet-to-be-determined players. Again, their initial endowment was 2.00€. Transfers to the public good were possible in steps of 0.10€. Participants were informed, that the multiplication factor was 3. For the LG, 15 situations were presented in a common format: “In the lottery, there is a chance of 50% to win 4.00€ and a chance of 50% to win 0.00€. The safe payment is X. I choose (…)”, with X ranging from 0.25€ to 3.75€ in steps of 0.25€.

After data collection was completed, for every participant one game was chosen by a random algorithm. If the LG was chosen, it was again randomly determined which of the 15 situations would be played off. If the participant had chosen the safe payment in this situation, he received the respective value in real money. If he had chosen the lottery, it was again randomly determined, whether he won or lost. In the first case he received 4.00€ in real money. If he lost, he was informed, that he had won nothing. If—in the first step—the TG was chosen, we randomly determined, whether the respective participant would act as Player 1 or Player 2. In either case, in the next step the other player was determined randomly. The index-participant was payed off according to his own and the other player’s decisions. If the PGG was chosen, the procedure was basically the same: Four other players were randomly chosen and the index-participants received a payoff dependent on their and his own transfers.

Statistical Methods

Questionnaire-measures were inspected for reliability using the McDonalds Omega statistic (Dunn et al. 2014). The first three self-placement items were recoded so that higher scores among all political items consistently represent higher conservatism. Since the six WoM accordance scores are by design (see methods) not independent from one another, they raise concern about multicollinearity. In fact, entering the six scores in a multiple regression analysis (OLS) led to Tolerances < 1 and Variance Inflation Factors > 10 for single predictors, indicating that these represent linear combinations of the others. Although excluding only one of the WoM-scores solved the problem, we believe that the choice which one to exclude is too arbitrary. Therefore, Pearson's correlation coefficients are reported for each of the individual WoM accordance score's association with game-outcomes. Standard demographic variables (age, gender, education) were controlled for by using partial correlations where necessary. For comparisons of correlations, z-tests were employed. As the respective measure of effect-size, q is reported.

Since the monetary transfers in every game represent metric variables, they allow for correlational and regression analyses. While the transfers in the PGG and the first move of the TG were regarded as direct measures of Cooperativeness and Trust, we used the mean of all retransfers in the TG’s second move as our measure of Reciprocity. With regard to the LG, we determined at which amount of the safe option the participant chose to stop gambling and to take the safe payment for the first time (Risk). Participants showing an unclear pattern, i.e. switching back to the lottery-option after having chosen the safe payment at least once before, were excluded from analyses concerning the LG because these patterns cannot be interpreted in terms of risk-affinity. Mediation analyses were conducted to assess and compare the power of SDO vs. RWA to mediate the associations between the political self-placement and game-outcomes. Indirect effects were tested for significance by bootstrapping, which is why the lower and upper limit of confidence intervals (LLCI and ULCI) are reported (Hayes 2017). To test our main hypothesis, multiple regression analyses were conducted. A political self-placement item or the composite WoM variable along with standard demographics were entered as regressors and game outcomes as regressands. Variance inflation factor (VIF) statistic was used to test for multicollinearity. Subsequently, for comparability with international and especially American data, we divided our sample in two groups (right-leaning vs. left-leaning) based on voting intention and past voting behavior. Here, votes for the AfD+++, FDP++ or CDU/CSU+ led to a classification as right-leaning, whereas votes for SPD−, Die Gruenen−− and Die Linke−−− led to a classification as left-leaning. Group comparisons were done by ANOVAS and ANCOVAs with standard demographics as covariates where appropriate. Hierarchical regression technique was used to assess whether political orientation variables are meaningful regressors of game outcomes beyond personality traits. All analyses were computed with IBM SPSS Statistics v. 24 and the PROCESS-Macro for SPPSS by Andrew Hayes (Hayes 2017). For Power analyses, G*Power (Faul et al. 2007, 2009) was used.

Results

Power Analyses

Because we strived to test for associations between the very broad construct political orientation and specific behavior in specified games, small effects were expected. Sensitivity analyses showed that a ρ of 0.13 could be detected with a reasonable power of 80% given our sample size and an α of 0.05. Of note, these estimates are based on the assumption of two-tailed tests, while the state of research, as outlined in the introduction, surely would justify directional hypotheses. However, we prefer giving this lower estimate of power, which—facing some dropouts for specific tests—also is more realistic. Some participants specifically dropped out for analyses entailing the Risk variable due to unclear response patterns, so we repeated sensitivity analysis for a subsample of 377 participants, representing the lowest limit of N for these analyses. Here, a ρ of 0.14 could be detected with a power of 80%. For multiple regression analyses and analyses of variance, sensitivity analysis yielded f2 measures of 0.02 (equals R2 = 0.02) or lower, also representing small effects.

Descriptive Statistics: NEO-FFI, SDO, RWA, Self-placements and WoM-Scores Per Party

Means, standard deviations and (in case of NEO-FFI, SDO and RWA) McDonald’s Omegas are presented in Table 1.

As can be seen by the mean values of the self-placement items, our sample is skewed to the right, i.e. people ascribing themselves to a left-wing orientation are overrepresented. Asked for their voting intention, 24.2% indicated to vote for Die Gruenen--, followed by the SPD− (17.2%), Die Linke--- (15.0%), CDU/CSU+ (14.5%), FDP++ (8.4%) and AfD+++ (3.1%). 10.4% indicated not to vote at all and 7.3% would vote for another, minor party. A different picture emerges when looking at the WoM-Outcomes: 47.7% show the highest accordance with Die Linke---, followed by Die Gruenen-- (25.8%), SPD− (17.2%), FDP++ (3.8%), AfD+++ (3.8%) and CDU/CSU+ (1.8%).

Analyses concerning gender effects on personality and political variables are depicted in Table 2. Age and educational status did not correlate significantly with political self-placements, whereas age showed small but significant correlations with WoM accordance scores with the SPD− (r = − 0.163, p = 0.001), the FDP++ (r = − 0.190, p < 0.001), Die Gruenen-- (r = − 0.114, p = 0.018) and the AfD+++ (r = 0.132, p = 0.006) as well as WoM_com (r = 144, p = 0.003). Educational status correlated only with the WoM-Score for Die Gruenen-- (r = 0.101, p = 0.037) but none of the others.

Concerning the personality-scores, age correlated significantly only with neuroticism (r = − 0.167, p = 0.001) but none of the others. Educational status showed small but significant correlations with Neuroticism (r = − 0.105, p = 0.030), Extraversion (r = 0.095, p = 0.049), Openness (r = 0.097, p = 0.045), Agreeableness (r = 0.148, p < 0.002) and Conscientiousness (r = 0.232, p < 0.001) as well as RWA (r = − 0.110, p = 0.023) but not with SDO.

The Association Between Political Orientation and Gaming Behavior

Regarding our game derived variables, we found differences between men and women only in Trust (F(1,431) = 14.019, p < 0.001, d = 0.36) with women (M = 1.17 €) transferring slightly less than men (M = 1.39 €). There were no significant gender differences for any of the other game-derived variables (Reciprocity: F(1,434) = 1.354, p = 0.245; Cooperativeness: F(1,426) = 0.030, p = 0.862; Risk: F(1,382) = 2.886, p = 0.090). Age showed small but significant correlations with both moves of the TG (Trust: r = 0.120, p = 0.013; Reciprocity: r = 0.109, p = 0.024) but not with Cooperativeness (r = 0.043, p = 0.382) and Risk (r = − 0.067, p = 0.192), whereas educational status did not correlate with any of them (all p’s > 0.218).

Table 3 depicts bivariate correlations between game-derived variables and the six WoM-Scores.

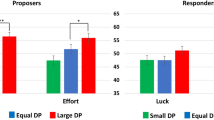

As Fig. 1 illustrates, the WoM-Scores concerning right- vs. left-of-center-parties show mirror-imaged relations with Cooperativeness and partially with Trust and Reciprocity, while Risk is not associated in any meaningful way with the WoM-Scores.

For the most part, there were no significant differences between the correlations of WoM-Scores with Trust vs. Cooperativeness (all p's > 0.06), with the exception of the WoM-AfD+++ and FDP++ scores being significantly stronger related to Cooperativeness than to Trust (zero-order: z = 2.07, p = 0.019; q = 0.11; z = 1.65, p = 0.05; q = 0.08; partial correlations: z = 1.81, p = 0.035, q = 0.10; z = 2.50, p = 0.007, q = 0.13). In a dual, parallel mediation model (F(3,441) = 10.36, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.07), SDO significantly mediated the association between the left–right self-placement and Cooperativeness (β = − 0.08, LLCI = − 0.13, ULCI = − 0.02) while RWA did not (β = − 0.04, LLCI = − 0.10, ULCI = 0.02). Of note, the contrast between indirect effects did not reach significance (β = 0.04, LLCI = − 0.06, ULCI = 0.13). In a second dual, parallel mediation model (F(3,445) = 7.66, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.05), RWA was found to significantly mediate the association between the left–right self-placement and Trust (β = − 0.10, LLCI = − 0.16, ULCI = − 0.05) while SDO did not (β = − 0.01, LLCI = − 0.06, ULCI = 0.05). Here, the contrast between indirect effects reached significance (β = − 0.10, LLCI = − 0.19, ULCI = − 0.01).

Due to substantial and theoretically plausible intercorrelations of the political self-placement items (see Online Appendix A2) we restricted regression analyses to the left–right self-placement to avoid obtaining biased estimators due to multicollinearity. Therefore, to assess the association between political orientation and game outcomes, two separate multiple regression analyses were conducted for Trust, Reciprocity, Cooperativeness and Risk as regressands each, with either the left–right self-placement or the composite WoM-score as regressors. Demographic variables were added if they showed significant bivariate correlations with the regressors or the regressand. Results are shown in Table 4. Regression models with Risk as the regressand, did not reach significance, both when the left–right self-placement and when age, gender and WoM_com were entered as regressors (N = 398, F(1,396) = 0.19, p = 0.663; N = 377, F(3,373) = 1.72, p = 0.163).

In the next step we conducted group-comparisons between right- and left-leaning participants, depicted in Fig. 2.

We found significant differences between participants intending to vote for a left-of-center vs. right-of-center party in Cooperativeness (F(1,365) = 11.204, p = 0.001, d = 0.35) and Trust (F(1,348) = 9.951, p = 0.002, d = 0.34; gender and age were controlled for) as well as a significant difference between participants having actually voted for a right-of-center vs. left-of-center party in 2013 in Cooperativeness (F(1,317) = 6.003, p = 0.015, d = 0.28). In both cases right-wingers showed lower transfers. Of note, there were no differences in Risk between these groups. Regarding Reciprocity, no significant group-differences emerged.

Finally, we performed hierarchical regression analyses to assess whether political orientation variables are meaningful regressors of game outcomes beyond personality traits. Demographic variables (age, gender, educational status) were entered in the first block, followed by the Big Five scores in the second and either the left–right self-placement or WoM_com in the third block. For Cooperativeness, neither the first (F(3,416) = 0.24, p = 0.872, adj. R2 = − 0.01), nor the second model (F(8,411) = 1.90, p = 0.059, adj. R2 = 0.02) reached significance. Adding the self-placement (β = − 0.15, t = − 2.79, p = 0.005), significantly increased R2 (ΔR2 = 0.02, p = 0.005) and yielded a significant regression model (F(9,410) = 2.58, p = 0.007, adj. R2 = 0.03). Adding WoM_com (β = − 0.15, t = − 2.72, p = 0.007) instead of the self-placement, led to the same result (ΔR2 = 0.02, p = 0.007; F(9,409) = 2.53, p = 0.008, adj. R2 = 0.03).

For Trust and Reciprocity, explained variance was not significantly increased when political orientation variables were entered in the third step (see Online Appendix A3 for full regression outputs).

Discussion

The present results hint to the possible relevance of political orientation for interactional behavior outside of the overtly political sphere: Right-leaning participants did show smaller contributions in the PGG than left-leaning participants. Furthermore, we saw significant relationships between the political self-placement, specific WoM-Scores, SDO and RWA on the one side and PGG and TG on the other side. Notably, the respective measures did not correlate with participant’s outcome in the LG, endorsed to check for general risk-tolerance as a potential distractor.

The specific pattern of results may be of special interest to theoretical conceptions of the psychological "core" of political orientation: Trust was associated with the political self-placement and WoM accordance scores with CDU/CSU+, Die Gruenen--, and Die Linke--. Furthermore, its association with political orientation seems to be mediated by RWA but not by SDO. For Cooperativeness, a different picture emerged: Here, correlations with the WoM-scores concerning the AfD+++ and the FDP++ also reached significance and were significantly stronger. Also, SDO was found to be a significant mediator of Cooperativeness' association with political orientation. This is interesting, as it—with all caution—may be interpreted in line with the “dual process model” proposed by Duckitt and Sibley (2010) which links RWA and SDO as motivational bases to the core-aspects of conservative ideology (namely resistance to change and tolerance of inequality; see Jost et al. 2003) whereby differing importance of both for each core-aspect becomes evident: Here, the TG was employed to yield a measure of behavioral trust. As outlined by the aforementioned authors, RWA is reflective of a view of the world as dangerous and threatening, so lower general trust among people high on RWA is expectable. Further, we argue, that this leads to higher accordance with the CDU/CSU+, a party associated with traditional values, conventionalism and stability. By contrast, the left-of-center parties Die Gruenen-- and Die Linke--- are associated with a less critical eye on the world, reflected for example in persistent admonitions to help and give asylum to refugees or support weak countries. Higher general trust should be related to a less threatening worldview and therefore with the approval of these parties’ stances on concrete issues, which is exactly what we found. On the other hand, SDO is proposed to reflect a view of the world as a competitive jungle, thereby constituting the motivational basis of tolerance of inequality. Reasonably, people scoring high on SDO should thus be expected to transfer lower amounts in the PGG, constituting a measure of cooperativeness. Furthermore, lower cooperativeness should thereby be related to the approval of “neoliberal” policies, stressing less regulations of the economy, meritocracy etc. These policies in Germany are pushed forward especially by the FDP++ and the AfD+++. Of note, facing the low effect-sizes and partially insignificant differences of associations, there is no doubt, that those inferences remain speculative here.

The lack of significant associations between the LG and nearly all political variables speaks for the validity of the mentioned results despite their undoubtedly modest height. Having said this, we—however—should ask ourselves whether one would reasonably expect associations of greater size between specific, behavioral measures based on the conception of a highly artificial interpersonal situation and indicators of one’s general ideas about how a whole country or the whole world would work best. Social psychology does address this issue by the term “principle of correspondence”, stating that high attitude-behavior relations are only expectable when target and action elements of both entities do correspond highly (Ajzen and Fishbein 1977), which clearly is not the case here. In light of this, the size of correlations we found is rather high than inconsiderably small. Searching for a sensible standard of comparison, the relation between broad personality traits and equally specific behavioral measures comes to mind. Here, our results of the hierarchical regression analyses suggest, that political orientation may be of additional value for explaining cooperative predispositions, even when information on a subject’s personality are at hand. Of note, the modest predictive power of the Big Five traits for game outcomes has been shown before: Lönnqvist et al. (2011) report correlations between the transferred amount in a Trust-Game and the Big Five traits ranging from − 0.12 to 0.30. So, in light of our findings, it seems justified to state, that indices of political orientation are similarly relevant for explaining behavioral outcomes compared to broad personality traits and even may increase explained variance of behavioral predispositions beyond those in some cases.

To us, the pattern of results clearly contradicts the initial concept of Alford and Hibbing (2007), who stated, that there may be personal, interpersonal and political temperaments that are largely distinct from each other (of note, in later work, the authors changed their opinion about that issue; Hibbing et al. 2014). The authors based their statement on a review of literature showing mainly non-significant differences between democrats and liberals or self-identified conservatives and liberals in gaming outcomes. So, how did we obtain positive results? First of all, we of course cannot exclude cultural differences between samples as a possible explanation. Interestingly, the only studies we know being successful in relating gaming behavior to political orientation are of European descent too: As outlined in the introduction, Van Lange et al. (2012) as well as Chirumbolo et al. (2016) categorized their participants by ascribing them to individualistic, competitive and prosocial orientations, based on the theory of social value orientation. They did so using the triple-dominance decomposed game (Van Lange et al. 1997), which faces the player with three options for allocating points to oneself and the other, and found that those with individualistic and competitive orientations endorsed stronger conservative political preferences than prosocials. By contrast, Anderson et al. (2004) did not find differences between participants with democratic vs. republican leanings and self-identified liberals vs. conservatives in the Trust- and the Public-Goods-Game. Likewise, Balliet et al. (2016) did not find higher transfers in a Trust-Game among Democrats vs. Liberals but merely ingroup-favoritism among both groups. So, do we have to accept, that political orientation is relevant for behavior in Europe but not in the US? We do not think so. Instead, there was one big difference in experimental design between our and the aforementioned studies, that is feasible to explain the differing results in our opinion: Both studies allowed for the partner(s) in games to have a massive impact on the behavior of the index-participant. Anderson et al. (2004) derived their dependent variables by averaging the transfers of 30 rounds of the PGG and the TG respectively. Critically, at the end of each round, feedback of the other player’s decisions was provided. Likewise, Balliet et al. (2016) provided their participants with information of their counterpart being a republican or democrat. By contrast, participants in our study had no idea, who they would actually be playing with. Accordingly, instructions in the study by Van Lange et al (2012), explicitly assured participants that they did not know the other and would never knowingly meet him in future. To us, it seems clear that information about the person one is interacting with can be way more relevant for the decision one has to make in the specific moment than one’s political orientation. So, there is no doubt that aspects of the partner and/or his behavior may influence trust and cooperativeness as various studies outlined in the introduction showed. It is well conceivable that this information overrides the small effects of political orientation. To give an obvious analogy, people will generally be more cautious when dealing with a known fraudster, thief or murderer than when dealing with a friend. These shifts in behavior are hardly attributable to dispositional factors, they are rather consequences of situational factors (which encompass the characteristics, personal history and past behavior of one’s opponent in game paradigms). Strictly speaking, trying to infer personal dispositions from behavioral adaptations like these would represent a perfect example of correspondence bias, i.e. drawing inferences about a person’s dispositions from behaviors which are completely explained by situational factors (Gilbert and Malone 1995). Likewise, denying the influence of personal dispositions on behavior can represent correspondence bias when there are strong situational influences. However, if these situational factors are not given, the effects of political orientation on decision making in game-paradigms are much more likely to occur. So, the question we wanted to answer was, whether the political orientation predisposes for a more trusting or cooperative behavior irrespective of any situational features, including the person one is interacting with. Preventing any information about this person and her behavior seemed to be a good way to us.

Aligning our results with those of former studies, the following picture emerges: conservative vs. liberal persons may have different behavioral predispositions related to cooperativeness, trust and reciprocity which emerge (only) when no information on their interaction partner is available. This may question the ecological validity or societal importance of our results: When will people ever interact with one another in perfect anonymity? On the other hand, positive implications for political practice may be derived: Presumably, neither conservatives nor liberals are "hardwired" to act in certain ways and—perhaps—uncooperative, distrustful or untrustworthy behavior in the political realm—as negative reactions to refugees, rejection of sexual, cultural and ethnical diversity etc. may be mitigated by personal contact and a more personal political debate. Also, there may be settings, where anonymous, “economic” interactions might not be that unlikely, for example at the stock exchange. Tax evasion also may be an example of one interacting with an anonymous “collective”. It would be an interesting project for further research to analyze, whether our results translate to these areas of real life. And again, detrimental behavior here—which may include too uncooperative behavior by conservatives but also too naïve acting by liberals for example—may be mitigated by personal contact to the ones affected.

As said before, cultural differences cannot be excluded as an explanation for the divergent results. Here, especially differences in the political systems (two-party vs. multi-party-system) and political history come to mind, but the extensive discussion of these would lead to far here. Anyway, we predict that our results can be replicated cross-culturally.

There are several limitations of the current study that need to be addressed. First and foremost, our sample was not representative of the entirety of voters in Germany: Our sample was rather left-wing, the average educational status was quite high and mean age quite low. These are pertinent problems in psychological science. Since we were not interested in creating an election forecast but to invest relationships of psychological relevance, we suspect, that a more representative sample would rather strengthen than diminish the effects we found, but this is speculative.

Power analyses showed that our sample size was sufficient to detect effects conventionally classified as small or very small. However, we cannot exclude having overseen even smaller effects with regard to associations between political orientation and Risk for example due to too low power. However, the question arises whether finding nominally significant effects with effect sizes conventionally classified as "not meaningful" are a worthwhile goal of scientific inquiry. The effects we showed with sufficient statistical power are small but—in our opinion—potentially meaningful for research and beyond as described above. Beside all advantages of the WoM, one has to recognize that it may not be a temporally stable measure of political orientation, although we think that people’s stances on issues touching core aspects of the political orientation will change rather slowly if at all.

Synoptically, one can say that we showed the behavioral significance of political orientation—operationalized in several ways—using game paradigms. To us, these results corroborate the idea of the political orientation being deeply seated in the human condition and influencing our way of behavior in everyday life. With respect to the study by Van Lange et al. (2012), Jost (2017, p. 193) wrote “If differences such as these turn out to be robust and generalizable to other behavioral domains, the practical implications of ideological asymmetries would be legion”. We fully agree with that and hope that our results play their part to adequately estimate the relevance and deep-rootedness of ideological differences. Ultimately, this could help to accept opposing views on the same issues, to overcome our lack of understanding of political opponents and to come to solutions in a way that is purely based on the better argument instead of hatred and contempt for the political opponent.

Data Availability

The data set (SPSS) and all appendices referred to in the manuscript are available here: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/9GMWFE.

References

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J., & Sanford, R. N. (1950). The authoritarian personality. New York: Harper.

Aichholzer, J. & Zeglovits, E. (2015). Balancierte Kurzskala autoritärer Einstellungen (B-RWA-6). Zusammenstellung sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1977). Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin, 84(5), 888.

Alford, J. R., & Hibbing, J. R. (2007). Personal, interpersonal, and political temperaments. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 614(1), 196–212.

Altemeyer, B. (1981). Right-wing authoritarianism. Manitoba: University Press.

Amodio, D. M., Jost, J. T., Master, S. L., & Yee, C. M. (2007). Neurocognitive correlates of liberalism and conservatism. Nature Neuroscience, 10(10), 1246–1247.

Anderson, L. R., Mellor, J. M., & Milyo, J. (2004). Do liberals play nice? The effects of party and political ideology in public goods and trust games. Experimental and Behavorial Economics. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-0984(05)13005-3.

Bakker, B., Schumacher, G., Gothreau, C., & Arceneaux, K. (2019). Conservatives and liberals have similar physiological responses to threats: Evidence from three replications. Psyarxiv. Retrieved August 1, 2019 from https://osf.io/js9r5/.

Balliet, D., Tybur, J. M., Wu, J., Antonellis, C., & Van Lange, P. A. (2016). Political ideology, trust, and cooperation: In-group favoritism among Republicans and Democrats during a US national election. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 62(4), 797–818.

Baumgartner, T., Heinrichs, M., Vonlanthen, A., Fischbacher, U., & Fehr, E. (2008). Oxytocin shapes the neural circuitry of trust and trust adaptation in humans. Neuron, 58(4), 639–650.

Berg, J., Dickhaut, J., & McCabe, K. (1995). Trust, reciprocity, and social history. Games and Economic Behavior, 10(1), 122–142.

Borkenau, P. & Ostendorf, F. (1993). NEO-Fünf-Faktoren Inventar (NEO-FFI) nach Costa und McCrae. Handanweisung. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Borkenau, P. & Ostendorf, F. (2008). NEO-FFI: NEO-Fünf-Faktoren-Inventar nach Costa und McCrae. Handanweisung. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Boyce, C. J., Wood, A. M., Daly, M., & Sedikides, C. (2015). Personality change following unemployment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(4), 991–1011.

Brocklebank, S., Lewis, G. J., & Bates, T. C. (2011). Personality accounts for stable preferences and expectations across a range of simple games. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(8), 881–886.

Brülhart, M., & Usunier, J. C. (2012). Does the trust game measure trust? Economics Letters, 115(1), 20–23.

Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (bpb). (2013). Wahl-O-Mat zur Bundestagswahl 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2019 from https://www.bpb.de/politik/wahlen/wahl-o-mat/45817/weitere-wahlen.

Butler, E. A., Gross, J. J., & Barnard, K. (2014). Testing the effects of suppression and reappraisal on emotional concordance using a multivariate multilevel model. Biological Psychology, 98, 6–18.

Chaudhuri, A. (2011). Sustaining cooperation in laboratory public goods experiments: A selective survey of the literature. Experimental Economics, 14(1), 47–83.

Chirumbolo, A., Leone, L., & Desimoni, M. (2016). The interpersonal roots of politics: Social value orientation, socio-political attitudes and prejudice. Personality and Individual Differences, 91, 144–153.

Civai & Hawes (2016). Game theory in neuroeconomics. In Reuter, M. & Montag, C. (Eds.), Neuroeconomics, (pp. 13-37). Heidelberg: Springer

Cochard, F., Van, P. N., & Willinger, M. (2004). Trusting behavior in a repeated investment game. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 55(1), 31–44.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Professional manual: Revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO five-factor inventory (NEO-FFI). Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Czibor, A., & Bereczkei, T. (2012). Machiavellian people’s success results from monitoring their partners. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(3), 202–206.

DeBruine, L. M. (2002). Facial resemblance enhances trust. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B: Biological Sciences, 269(1498), 1307–1312.

De Dreu, C. K., Greer, L. L., Handgraaf, M. J., Shalvi, S., Van Kleef, G. A., Baas, M., et al. (2010). The neuropeptide oxytocin regulates parochial altruism in intergroup conflict among humans. Science, 328(5984), 1408–1411.

Delgado, M. R., Frank, R. H., & Phelps, E. A. (2005). Perceptions of moral character modulate the neural systems of reward during the trust game. Nature Neuroscience, 8, 1611–1618.

Deutsch, M. (1949). An experimental study of the effects of cooperation and competition upon group process. Human Relations, 2, 199–231.

Deutsch, M. (1958). Trust and suspicion. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2, 265–279.

Dodd, M. D., Balzer, A., Jacobs, C. M., Gruszczynski, M. W., Smith, K. B., & Hibbing, J. R. (2012). The political left rolls with the good; the political right confronts the bad. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Biological Sciences, 367(1589), 640–649.

Duckitt, J., & Fisher, K. (2003). The impact of social threat on worldview and ideological attitudes. Political Psychology, 24(1), 199–222.

Duckitt, J., & Sibley, C. G. (2010). Personality, ideology, prejudice, and politics: A dual-process motivational model. Journal of Personality, 78(6), 1861–1894.

Dunn, T. J., Baguley, T., & Brunsden, V. (2014). From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. British Journal of Psychology, 105(3), 399–412.

Englmaier, F., & Gebhardt, G. (2016). Social dilemmas in the laboratory and in the field. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 128, 85–96.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149–1160.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191.

Fehr, E., Fischbacher, U., Von Rosenbladt, B., Schupp, J. & Wagner, G. (2003). A nation-wide laboratory: Examining trust and trustworthiness by integrating behavioral experiments into representative survey. IZA Discussion Paper No. 715, Bonn, Germany

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(3), 817–868.

Gilbert, D. T., & Malone, P. S. (1995). The Correspondence Bias. Psychological Bulletin, 117(1), 21–38.

Glaeser, E. L., Laibson, D. I., Scheinkman, J. A., & Soutter, C. L. (2000). Measuring trust. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(3), 811–846.

Guimond, S., Dambrun, M., Michinov, N., & Duarte, S. (2003). Does social dominance generate prejudice? Integrating individual and contextual determinants of intergroup cognitions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 697–721.

Gunnthorsdottir, A., McCabe, K., & Smith, V. (2002). Using the Machiavellianism instrument to predict trustworthiness in a bargaining game. Journal of Economic Psychology, 23(1), 49–66.

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation and conditional process analysis (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Hibbing, J. R., Smith, K. B., & Alford, J. R. (2014). Differences in negativity bias underlie variations in political ideology. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 37(3), 297–307.

Higgins, E. T. (1998). Promotion and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational principle. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 30, 1–45.

Infratest dimap. (2015). Die Positionierung der politischen Parteien im Links-Rechts-Kontinuum. Retrieved June 5, 2018 from https://www.infratest-dimap.de/ulpoads/media/LinksRechts_Nov2015_01.pdf.

Janoff-Bulman, R. (2009). To provide or protect: Motivational bases of political liberalism and conservatism. Psychological Inquiry, 20(3), 120–128.

Jost, J. T. (2006). The end of the end of ideology. The American Psychologist, 61(7), 651–670.

Jost, J. T. (2017). Ideological Asymmetries and the essence of political psychology. Political Psychology, 38(2), 167–208.

Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., & Sulloway, F. J. (2003). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 129(3), 339–375.

Kanai, R., Feilden, T., Firth, C., & Rees, G. (2011). Political orientations are correlated with brain structure in young adults. Current Biology, 21(8), 677–680.

Kosfeld, M., Heinrichs, M., Zak, P. J., Fischbacher, U., & Fehr, E. (2005). Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature, 435(7042), 673–676.

Krueger, F., McCabe, K., Moll, J., Kriegeskorte, N., Zahn, R., Strenziok, M., et al. (2007). Neural correlates of trust. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104, 20084–20089.

Lane, A., Luminet, O., Rimé, B., Gross, J. J., de Timary, P., & Mikolajczak, M. (2013). Oxytocin increases willingness to socially share one's emotions. International Journal of Psychology, 48, 676–681.

LeDoux, J. (2003). The emotional brain, fear, and the amygdala. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology, 23(4–5), 727–738.

LeDoux, J. E., & Pine, D. S. (2016). Using neuroscience to help understand fear and anxiety: A two-system framework. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(11), 1083–1093.

Lönnqvist, J. E., Verkasalo, M., & Walkowitz, G. (2011). It pays to pay–Big Five personality influences on co-operative behavior in an incentivized and hypothetical prisoner’s dilemma game. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(2), 300–304.

Mikolajczak, M., Gross, J. J., Lane, A., Corneille, O., de Timary, P., & Luminet, O. (2010). Oxytocin makes people trusting, not gullible. Psychological Science, 21, 1072–1074.

Nave, G., Camerer, C., & McCullough, M. (2015). Does oxytocin increase trust in humans? A critical review of research. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10, 772–789.

Oxley, D. R., Smith, K. B., Alford, J. R., Hibbing, M. V., Miller, J. L., Scalora, M., et al. (2008). Political attitudes vary with physiological traits. Science, 321(5896), 1667–1670.

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Malle, B. F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(4), 741.

Shook, N. J., & Fazio, R. H. (2009). Political ideology, exploration of novel stimuli, and attitude formation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 995–998.

Sibley, C. G., & Duckitt, J. (2008). Personality and prejudice: A meta-analysis and theoretical review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12(3), 248–279.

Specht, J., Egloff, B., & Schmukle, S. C. (2011). Stability and change of personality across the life course: The impact of age and major life events on mean-level and rank-order stability of the Big Five. Journal of personality and social psychology, 101(4), 862–882.

Van Lange, P. A., Bekkers, R., Chirumbolo, A., & Leone, L. (2012). Are conservatives less likely to be prosocial than liberals? From games to ideology, political preferences and voting. European Journal of Personality, 26(5), 461–473.

Van Lange, P. A., De Bruin, E., Otten, W., & Joireman, J. A. (1997). Development of prosocial, individualistic, and competitive orientations: Theory and preliminary evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(4), 733.

Von Neumann, J., & Morgenstern, O. (2007). Theory of games and economic behavior. Princeton: University Press.

Webster, D. M., & Kruglanski, A. W. (1994). Individual differences in need for cognitive closure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 1049–1062.

Wilson, G. D., & Patterson, J. R. (1968). A new measure of conservatism. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 7(4), 264–269.

Zak, P. J., Stanton, A. A., & Ahmadi, S. (2007). Oxytocin increases generosity in humans. PLoS ONE, 2, e1128.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed conception and design of the study. TG organized the database, performed the statistical analyses and wrote the first draft, the revised version and the revision memorandum. MR supervised writing at all stages.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grünhage, T., Reuter, M. Political Orientation is Associated with Behavior in Public-Goods- and Trust-Games. Polit Behav 44, 23–48 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09606-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09606-5