Abstract

Large partisan gaps in reports of factual beliefs have fueled concerns about citizens’ competence and ability to hold representatives accountable. In three separate studies, we reconsider the evidence for one prominent explanation of these gaps—motivated learning. We extend a recent study on motivated learning that asks respondents to deduce the conclusion supported by numerical data. We offer a random set of respondents a small financial incentive to accurately report what they have learned. We find that a portion of what is taken as motivated learning is instead motivated responding. That is, without incentives, some respondents give incorrect but congenial answers when they have correct but uncongenial information. Relatedly, respondents exhibit little bias in recalling the data. However, incentivizing people to faithfully report uncongenial facts increases bias in their judgments of the credibility of what they have learned. In all, our findings suggest that motivated learning is less common than what the literature suggests, but also that there is a whack-a-mole nature to bias, with reduction in bias in one place being offset by increase in another place.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Nyhan and Reifler test motivated learning using two-sided information flows. They instill false beliefs in respondents via misleading news stories and then attempt to reduce misperceptions with corrective stories. While this design lends external validity to their study, a one-sided context without contradictory information would afford a stricter test of motivated learning.

It is possible, even likely, that motivated responding also operates outside the survey context, explaining which beliefs people reveal in discussions with social networks, for example. However, in this paper, we focus on motivated responding in surveys.

We do not incentivize study ratings, because unlike the question about the study’s result, ratings are inherently subjective. The logic of providing incentives to be accurate on subjective questions is unclear. Correspondingly, even if we were to provide incentives, we would not be able to interpret the results unambiguously.

Attitudes in our study are similar to Americans’ attitudes in two nationally representative surveys. A CBS/New York Times Survey from January 2013 finds that 34% of Americans favor “a federal law requiring a nationwide ban on people other than law enforcement carrying concealed weapons” (including 19% of Republicans a 52% of Democrats). And an Associated Press/GfK Poll from January 2015 finds that 77% favor raising the federal minimum wage (from $7.25/h).

Kahan et al. (2017) define congeniality on the basis of party identification and ideology. However, overlap between a partisanship - ideology composite and attitudes toward concealed carry is considerably short of 100%. Across the three studies, 47% of self-described liberal Democrats oppose a ban on concealed carry, and 15% of self-described conservative Republicans favor such a ban. We therefore opt for coding congeniality in terms of the attitude most directly related to the data being. Recoding congeniality on the basis of party identification and ideology, following Kahan et al., results in a substantively similar congeniality effect (see “Subsetting Respondents by ‘Ideological Worldview’” in SI).

We subset high-numeracy respondents in Study 2 to ensure commensurability with Study 1. For concealed carry task results separated out by study, see SI Figs. 5 and 6 in “Covariance Detection Task Results by Study”.

For equivalent logistic regressions, see SI Tables 7 and 8 in “Concealed Carry Task Results as Logistic Regressions”.

In Study 2, only 129 respondents (15%) oppose raising the minimum wage. Pooling them with opponents in Study 3 yields a large enough sample to analyze. We obtain substantively similar results we see when analyze each study separately (see SI Figs. 7 and 8 in “Covariance Detection Task Results by Study”).

One possible explanation for this finding is that behavior in this task was affected by the previous task on concealed carry, since we did not randomize task order. We explore this possibility in “Assessing Spillover” in the SI but find little support for it. Another, related possibility is that respondents mistook the row labels in the second task to be parallel to the row labels in the first task (i.e., cities enacting the given policy are always in the first row). Properly testing this hypothesis (e.g., by fully randomizing row and column labels, and task order) is beyond the scope of this study.

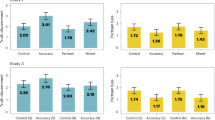

Pooling concealed carry supporters and opponents, we find that ratings increase from 4.79 if the study is uncongenial to 5.02 if the result supported by the study is congenial (\(t = 1.79\), \(p = .04\)). With incentives, the effect is .42 (\(t=2.30\), \(p=.01\)), and in the absence of incentives, the effect is only .08 (\(t=.46\), \(p=.32\)). All t-tests reported here are one-tailed.

In the minimum wage task, 23% of respondents are certain of their answer, while only 4% are certain and incorrect. We present these results in more detail in SI Table 11 in “How Confident are Respondents in Their Answers?”.

References

Ahler, D., & Sood, G. (2016). The parties in our heads: Misperceptions about party composition and their consequences. Working paper.

Arceneaux, K., & Vander Wielen, R. J. (2013). The effects of need for cognition and need for affect on partisan evaluations. Political Psychology, 34(1), 23–42.

Bartels, L. M. (2002). Beyond the running tally: Partisan bias in political perceptions. Political Behavior, 24(2), 117–150.

Bechlivanidis, C., & Lagnado, D. A. (2013). Does the “why” tell us the “when”? Psychological Science, 24(8), 1563–1572.

Berinsky, A. J., Huber, G. J., & Lenz, G. S. (2012). Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk. Political Analysis, 20(3), 351–368.

Bisgaard, M. (2015). Bias will find a way: Economic perceptions, attributions of blame, and partisan-motivated reasoning during crisis. The Journal of Politics, 77(3), 849–860.

Blais, A., Gidengil, E., Fournier, P., Nevitte, N., Everitt, J., & Kim, J. (2010). Political judgments, perceptions of facts, and partisan effects. Electoral Studies, 29(1), 1–12.

Bolsen, T., Druckman, J. N., & Cook, F. L. (2014). The influence on partisan motivated reasoning on public opinion. Political Behavior, 36(2), 235–262.

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–5.

Bullock, J. G., Gerber, A. S., Hill, S. J., & Huber, G. A. (2015). Partisan bias in factual beliefs about politics. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 10(4), 519–578.

Chaiken, S., & Maheswaran, D. (1994). Heuristic processing can bias systematic processing: Effects of source credibility, argument ambiguity, and task importance on attitude judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3(66), 460–473.

Chambers, J. R., Swan, L. K., & Heesacker, M. (2014). Better off than we know: Distorted perceptions of incomes and income inequality in america. Psychological Science, 25(2), 613–618.

Chambers, J. R., Swan, L. K., & Heesacker, M. (2015). Perceptions of U.S. social mobility are divided (and distorted) along ideological lines. Psychological Science, 26(4), 413–423.

Crawford, J. T., Kay, S. A., & Duke, K. E. (2015). Speaking out of both sides of their mouths: Biased political judgments within (and between) individuals. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6(4), 422–430.

Crawford, J. T., & Xhambazi, E. (2015). Predicting political biases against the Occupy Wall Street and Tea Party movements. Political Psychology, 36(1), 111–121.

Dawson, E., Gilovich, T., & Regan, D. T. (2002a). Motivated reasoning and performance on the Wason selection task. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(10), 1379–1387.

Dawson, E., Gilovich, T., & Regan, D. T. (2002b). Motivated reasoning and susceptibility to the “Cell A” bias. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Ditto, P. H., & Lopez, D. F. (1992). Motivated skepticism: Use of differential decision criteria for preferred and nonpreferred conclusions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4(63), 568–584.

Ditto, P. H., Scepansky, J. A., Munro, G. D., Apanovitch, A. M., & Lockhart, L. K. (1998). Motivated sensitivity to preference-inconsistent information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1(75), 53–69.

Edwards, K., & Smith, E. E. (1996). A disconfirmation bias in the evaluation of arguments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(1), 5.

Gaines, B. J., Kuklinski, J. H., Quirk, P. J., Peyton, B., & Verkuilen, J. (2007). Same facts, different interpretations: Partisan motivation and opinion on Iraq. Journal of Politics, 69(4), 957–974.

Gerber, A. S., & Huber, G. A. (2009). Partisanship and economic behavior: Do partisan differences in economic forecasts predict real economic behavior? American Political Science Review, 103(3), 407–426.

Gilens, M. (2001). Political ignorance and collective policy preferences. American Political Science Review, 95(2), 379–396.

Gilovich, T. D. (1991). How we know what isn’t so: The fallibility of human reason in everyday life. New York: The Free Press.

Hastorf, A. H., & Cantril, H. (1954). They saw a game: A case study. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 49(1), 129.

Hochschild, J. L. (2001). Where you stand depends on what you see: Connections among values, perceptions of fact, and political prescriptions. In J. H. Kuklinski (Ed.), Citizens and politics: Perspectives from political psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(3), 405–431.

Iyengar, S., & Westwood, S. J. (2015). Fear and loathing across party lines: New evidence on group polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 690–707.

Jacobson, G. (2010). Perception, memory, and partisan polarization on the Iraq War. Political Science Quarterly, 1(125), 31–56.

Jerit, J., & Barabas, J. (2012). Partisan perceptual bias and the information environment. Journal of Politics, 74(3), 672–684.

Kahan, D. M. (2013). Ideology, motivated reasoning, and cognitive reflection. Judgment and Decision Making, 8(4), 407–424.

Kahan, D. M., Peters, E., Dawson, E. C., & Slovic, P. (2017). Motivated numeracy and enlightened self-government. Behavioural Public Policy, Forthcoming. Yale Law School, Public Law Working Paper No. 307. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2319992.

Kahneman, D. (2013). The marvels and flaws of intuitive thinking. In J. Brockman (Ed.), Thinking: The new science of decision-making, problem-solving, and prediction. New York: Harper Collins.

Kim, S., Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2010). A computational model of the citizen as motivated reasoner: Modeling the dynamics of the 2000 presidential election. Political Behavior, 32(1), 1–28.

Kruglanski, A. W., & Webster, D. M. (1996). Motivated closing of the mind: “Seizing” and “freezing”. Psychological Review, 103(2), 263–283.

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 480–498.

Lau, R. R., Sears, D. O., & Jessor, T. (1990). Fact or artifact revisited: Survey instrument effects and pocketbook politics. Political Behavior, 12(3), 217–242.

Lebo, M. J., & Cassino, D. (2007). The aggregated consequences of motivated reasoning and the dynamics of partisan presidential approval. Political Psychology, 28(6), 719–746.

Lord, C. G., Ross, L., & Lepper, M. R. (1979). Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(11), 2098–2109.

Luskin, R. C., & Bullock, J. G. (2011). “Don’t know” means “don’t know”: DK responses and the public’s level of political knowledge. The Journal of Politics, 73(2), 547–557.

Luskin, R. C., Sood, G., & Blank, J. (2013). The waters of Casablanca: Political misinformation (and knowledge and ignorance). Unpublished manuscript.

Lyons, J., & Jaeger, W. P. (2014). Who do voters blame for policy failure? Information and the partisan assignment of blame. State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 114(3), 321–341.

Mata, A., Garcia-Marques, L., Ferreira, M. B., & Mendonça, C. (2015a). Goal-driven reasoning overcomes cell D neglect in contingency judgements. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 27(2), 238–249.

Mata, A., Sherman, S. J., Ferreira, M. B., & Mendonça, C. (2015b). Strategic numeracy: Self-serving reasoning about health statistics. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 37(3), 165–173.

Muirhead, R. (2013). The case for party loyalty. In S. Levinson, J. Parker, & P. Woodruff (Eds.), Loyalty. New York: New York University Press.

Mullinix, K. J., Leeper, T. J., Druckman, J. N., & Freese, J. (2015). The generalizability of survey experiments. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 2(2), 109–138.

Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, 2(2), 175–220.

Nyhan, B. (2010). Why the “death panel” myth wouldn’t die: Misinformation in the health care reform debate. The Forum, 8(1), 5.

Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2010). When corrections fail: The persistence of political misperceptions. Political Behavior, 32(2), 303–330.

Palmer, H. D., & Duch, R. M. (2001). Do surveys provide representative or whimsical assessments of the economy? Political Analysis, 9(1), 58–77.

Paolacci, G., & Chandler, J. (2014). Inside the Turk: Understanding Mechanical Turk as a participant pool. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(3), 184–188.

Prior, M. (2013). Media and political polarization. Annual Review of Political Science, 16, 101–127.

Prior, M., & Lupia, A. (2008). Money, time, and political knowledge: Distinguishing quick recall and political learning skills. American Journal of Political Science, 52(1), 169–183.

Prior, M., Sood, G., & Khanna, K. (2015). You cannot be serious: The impact of accuracy incentives on partisan bias in reports of economic perceptions. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 10(4), 489–518.

Sears, D. O., & Lau, R. R. (1983). Apparently self-interested political preferences. American Journal of Political Science, 27(2), 223–252.

Shani, D. (2006). Knowing your true colors: Can knowledge correct for partisan bias in Political perceptions? Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago, IL.

Shapiro, R. Y., & Bloch-Elkon, Y. (2008). Do the facts speak for themselves? Partisan disagreement as a challenge to democratic competence. Critical Review, 20(1–2), 115–139.

Stroud, N. J. (2010). Polarization and partisan selective exposure. Journal of Communication, 60(3), 556–576.

Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 755–769.

Thibodeau, P., Peebles, M. M., Grodner, D. J., & Durgin, F. H. (2015). The wished-for always wins until the winner was inevitable all along: Motivated reasoning and belief bias regulate emotion during elections. Political Psychology, 36(4), 431–448.

Weller, J. A., Dieckmann, N. F., Tusler, M., Mertz, C. K., Burns, W. J., & Peters, E. (2012). Development and testing of an abbreviated numeracy scale: A Rasch analysis approach. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 26(2), 198–212.

Wilcox, N., & Wlezien, C. (1993). The contamination of responses to survey items: Economic perceptions and political judgments. Political Analysis, 5(1), 181–213.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Princeton Research in Experimental Social Science (PRESS) for financial support. We are also very grateful to Dan Kahan for generously sharing experimental design details; Doug Ahler, Martin Bisgaard, Katie McCabe, Peter Mohanty, and Markus Prior for insightful comments on a previous draft; participants of the PRESS workshop for suggestions about the experimental design; and finally, the editor of this journal and three reviewers for their critical feedback and guidance. The data and code necessary to replicate the results in this paper are available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/polbehavior.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khanna, K., Sood, G. Motivated Responding in Studies of Factual Learning. Polit Behav 40, 79–101 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-017-9395-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-017-9395-7