Abstract

We contend that a candidate’s decision to exit from a U.S. presidential nomination campaign is a function of three sets of considerations: the potential for profile elevation, party-related costs, and updated perceptions of competitiveness. We analyze data from eleven post-reform presidential nomination campaigns and find support for all three considerations. Specifically, our results suggest that in addition to candidates’ competitiveness, the decision to withdraw is a function of candidates’ closeness to their party and ability to raise their profile. At the same time, some of our results contradict the conventional wisdom regarding presidential nomination campaigns, as we find no evidence that media coverage or cash on hand directly affect the duration of a nomination candidacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A defining feature of the selection of presidential nominees in the United States is that the primary elections and caucuses used to choose delegates to the parties’ national conventions occur in a series of discrete events over an extended period of time. At the same time, it is often clear which candidate will win their party’s nomination before voters or caucus-goers in some states have the opportunity to register their preferences. Moreover, most of the candidates vying for their party’s nomination withdraw well before the last delegate selecting event has been held. This shrinking of the candidate field is often referred to as the winnowing process.

For many candidates, however, there is a substantial lag between the recognition that they will not win the nomination and the termination of their campaigns. This presents scholars with an interesting theoretical puzzle: why do candidates continue to campaign, if only for a short period of time, after it has become almost certain they will not win the nomination? More generally, what explains why and when candidates seeking their party’s nomination will exit from the campaign?

Given both the theoretical and substantive importance of the winnowing process, the relative scarcity of systematic studies attempting to explain candidate termination of nomination campaigns is somewhat surprising. Aldrich (1980), in perhaps the first attempt to address this process (although see Matthews 1978), argues that the winnowing of candidates is a function of the initial uncertainty associated with the large and complex candidate fields that are the norm in the post-reform era.Footnote 1 The end result is that candidates who are unable to gain traction will quickly leave the race. Steger et al.’s (2002) descriptive analysis of candidate attrition from 1912 to 2000 supports this contention as they find that as candidate fields have become larger in the post-reform era, winnowing has become an important attribute of nomination competition. More recently, Norrander (2006) models the duration of a candidate’s time in the race as being a function of variables largely determined at the outset of the race. In particular, she points to the curvilinear effect that fundraising has on the length of a candidacy, finding that well-financed and poorly financed candidates appear to stay in the race longer than those who are moderately financed. Haynes et al. (2004) do not contest the importance of money, but focus their attention on the role that media coverage plays in determining the likelihood of a candidate withdrawing from a race.

We build on these and other studies (e.g., Steger et al. 2004; Steger 2008) to develop a model of candidate withdrawal that emphasizes the cost–benefit calculus associated with entering and remaining in a presidential nomination contest. Specifically, our model recognizes that candidates’ decisions to compete are shaped not only by the goal of winning, but also by the potential profile-raising benefits that may result from contesting their party’s presidential nomination (Steger et al. 2004). At the same time, the pursuit of these benefits is likely to be tempered by party-related costs that may result from lengthy losing nomination candidacies (Norrander 2006). The extent to which staying in the race helps candidates achieve their goals of profile-raising and/or winning the nomination is also affected by campaign dynamics as we expect that candidates will respond to retrospective and prospective indicators of their electoral competitiveness.

We test several hypotheses drawn from this framework by estimating a model of the withdrawal of candidates from presidential nomination campaigns from 1980 to 2008. The results of our analysis indicate that variation in the potential to improve a candidate’s profile and variation in the party-related costs of staying in the race affect the day-to-day likelihood of a candidate withdrawing from the race. Furthermore, decisions to stay in the race or withdraw are affected by indicators of competitiveness such as relative poll standings and the degree to which there is uncertainty as to who will win the nomination. Some of our results contradict the conventional wisdom regarding presidential nomination campaigns (e.g., Haynes et al. 2004; Norrander 2006; Steger et al. 2004), as we find no evidence that media coverage and the amount of cash on hand directly affect the duration of a candidacy.

Candidate Motivations and the Decision to Continue a Nomination Campaign

Prior investigations of post-reform presidential nomination campaigns typically treat the vast majority of candidates as if they pursue a single goal: winning their party’s nomination.Footnote 2 This assumption may be misplaced, given that only a fraction of the candidates contending for a nomination have a realistic chance of winning. Furthermore, a clear frontrunner often emerges well before the first delegate has been allocated (Cohen et al. 2008). Given the financial and opportunity costs associated with campaigning for a major party nomination, a theory of candidate behavior based on the assumption that all (or at least most) candidates are exclusively motivated by winning the nomination should predict small field sizes and quick exits from a race that appears to have been won by someone else. Empirically, however, we see sizable candidate fields and considerable variation in the length of time that candidates continue to vie for a nomination. Indeed, some losing candidates never drop out of the race.

This disjuncture between theoretical prediction and empirical observation creates an interesting puzzle. If the frontrunner coming out of the “invisible” or “money” primary (i.e., the period leading up to the Iowa caucus) wins the nomination in nearly every instance (Adkins and Dowdle 2000, 2001a, b; Cohen et al. 2008), what explains the continued participation of the rest of the field and the duration of these unsuccessful campaigns?

Our contention is that not all candidates participate in nomination campaigns with the exclusive goal of winning their party’s nomination. While at the outset candidates may have a scenario by which they believe that they can win the nomination (Gurian 1986), we argue that candidates also enter and remain active in order to raise their profile, nationally and within their party. In essence, a presidential nomination bid can increase a candidate’s political capital, which can be spent in numerous ways; on a future presidential run or to gain consideration as a vice presidential nominee or cabinet member. And as Steger et al. (2004) suggest, profile raising and the resulting increase in political capital also benefits “issue” or “advocacy” candidates. Candidates who seek to bring attention to a particular issue or move the party in a certain direction will be more successful if they maximize their national profile.

Thus, in light of these considerations, we argue that there are two types of benefits to entering and then remaining in a presidential nomination campaign: winning the nomination and profile elevation. Obviously, only one candidate will enjoy the first of these benefits. Multiple candidates, however, can elevate their profiles and build political capital. It is important to note that if a candidate were to solely run with the hope of winning the nomination and there is any meaningful cost to staying in the race, s/he will quickly drop out of the race when it becomes apparent that another candidate will be the winner. On the other hand, profile-motivated candidates may continue to campaign after it becomes clear that they will not win because it takes time to build the reputation and recognition these candidates seek. These candidates may continue to increase their visibility and build political capital even as it becomes apparent that they will not become the nominee.

With this pair of candidate motivations in mind, we contend that the decision to exit from a nomination campaign will be a function of three sets of considerations. First, the likelihood of a candidate withdrawing from the race on a given day will be smaller (and thus, candidacy duration will be longer) for candidates who have more to gain, and are gaining, in terms of profile elevation. Second, candidates will be more likely to drop out (and thus, candidacy duration will be shorter) if they face greater costs in terms of damage to the party and their reputation within the party (Norrander 2006). The third set of considerations affecting the duration of nomination candidacies focus on changes in candidates’ assessments of their competitiveness. Both the likelihood of winning the nomination and the ability to profile-raise will depend upon the extent to which a candidate is competitive.

The Profile-Raising Benefit of Continuing a Candidacy

The ability of candidates to use their candidacies to raise their profiles will vary depending upon a candidate’s initial profile. A nomination campaign offers fewer profile-raising benefits to candidates who already have high profiles. Low-profile candidates, however, can benefit greatly if they can raise their profiles through a moderately successful nomination campaign. Thus, we hypothesize that candidates with high initial profile levels will terminate their candidacies more quickly than candidates with low initial profiles, all else equal. Put in duration model terms, we expect high profile candidates to have a greater hazard of withdrawing from the race on a given day.

The extent to which staying in a nomination race raises the profile of a candidate should also depend on the amount of media coverage a candidate is able to attract. While the media is not the only source of information about the candidates, for many voters the media serve as an important source. The more that the media is covering a candidate, the more there will be profile-raising benefits associated with staying in the race. Thus, our second hypothesis is that as recent media coverage of a candidate increases this will decrease the hazard of the candidate withdrawing from the race (Haynes et al. 2004).

The Cost of Continuing a Losing Candidacy

While there may be benefits to remaining in a presidential nomination race past the point at which it is apparent that another candidate will be the eventual nominee, there also may be significant costs to staying in the race too long. For our purposes, the most significant costs are any potential damage to either the eventual nominee’s general election prospects or a candidate’s reputation within the party.

The cost associated with this former consideration stems from the possibility that forcing the presumed winner-to-be to continue campaigning against a fellow partisan, instead of turning his or her sights and resources to the likely opponent in the general election, may undermine the party’s prospects in November.Footnote 3 To the extent that it is perceived that a losing candidate’s continuation in the nomination race hurts the party in the general election, this candidate’s reputation in the party will be diminished. Indeed, Norrander (2006, p. 504) finds that all else equal, “traditional candidates” (defined as those who have held high elective office) who are more closely tied to their party’s mainstream “find it more rational to exit the presidential contest to maintain cordial relations with party elites and their fellow partisans in the government.” Moreover, as the work of Cohen et al. (2008) suggests, party costs and remaining in the good graces of party elites and other “policy demanders” may be a significant factor in candidates’ decision making given the prominent role that these actors play in shaping perceptions of candidate viability.

At the same time, the value of intra-party reputation varies according to the degree that candidates are connected to their political party. Candidates who are closely connected to their party will pay a greater cost for maintaining a losing nomination bid because they care more about both their party’s prospects in the general election and their reputation within the party. Party outsiders will be less concerned about maintaining a reputation within their party and not as worried about hurting a mainstream candidate’s chances of winning the general election. We hypothesize that the more closely connected a candidate is to his or her party, the greater the hazard of ending his or her candidacy on a given day.

Our argument here is consistent with Steger (2008) and Steger et al.’s (2004) contentions about the behavior of advocacy candidates. Because these candidates seek to alter their party’s agenda and often serve as an outlet for primary voters who are dissatisfied with the other candidates in the field (Norrander 2000; Steger 2008) and perhaps, the direction of the party more generally, they cannot be considered part of the party mainstream. Thus, those deemed as advocacy or non-traditional candidates by others fit into our framework as candidates who are not particularly connected to their party, care less about party-associated costs, and as a result, will remain in the race longer than those strongly connected to the party.

Dynamic Perceptions of Competitiveness and the Certainty of Losing

Thus far, we have discussed the costs and benefits of continuing a nomination campaign largely in terms of static candidate characteristics, (i.e., they are fixed for a given candidate in a particular nomination campaign). Consistent with prior work (Aldrich 1980; Bartels 1988; Haynes et al. 2004), we also expect that candidates will respond to dynamic indicators of their competitiveness in the race. More accurately, candidates want to be competitive and want to be perceived by others (e.g., the media or party elites) as competitive. Indeed, competitiveness matters for both of the motivations underlying candidacies laid out above. Competitiveness indicates the likelihood of winning the nomination and also increases a candidate’s ability to develop name recognition and otherwise profile-raise. Put simply, the more competitive candidates are the longer they will stay in the race.

The ability to assess competitiveness necessitates that candidates have access to relevant information. On this front, we contend that candidates will rely on both retrospective and prospective indicators to assess their competitiveness. There are at least two important retrospective indicators of competitiveness. The first of these is recent electoral outcomes. While a candidate’s performance in one state is not a perfect predictor of performance in another state, it is a reasonable predictor of future outcomes.Footnote 4 We hypothesize that a candidate will be less likely to exit from the race when he or she wins or finishes close to the winner of the most recent primary contest. Candidates who do not fare well in the most recent contests will be perceived by themselves and others as not being competitive and will more quickly drop out.

How well a candidate is faring in the formal allocation of delegates is a second retrospective indicator of competitiveness. The more delegates secured by a candidate, the better their prospects of winning the nomination or at least appearing to be a serious contender. Accordingly, we expect that greater delegate tallies will decrease the likelihood of candidacy termination while weak or non-existent delegate totals will increase this likelihood.

Regardless of past performance, we expect prospective evaluations of competitiveness will also influence whether a candidate chooses to continue campaigning or withdraw from the race. The size of the candidate field at time t is the bluntest indicator of prospective performance.Footnote 5 All else equal, the more competitors a candidate faces the less likely the candidate is to win electoral contests and the quicker the candidate will drop out. The relative position of a candidate in the national polls provides additional, finer-grained information about how a candidate is likely to perform in subsequent contests. Better poll standings will cause candidates to extend their campaigns as they forecast positive electoral outcomes in the near future.

Given the importance that money plays in candidates’ abilities to campaign (Norrander 2006), candidates will also consider their available resources. The more money a campaign has at its disposal, the more competitive a candidate will be in future contests (Aldrich 1980; Haynes et al. 1997; Steger et al. 2004). Or put differently, available cash reserves indicate not only candidates’ relative positions at a given point in time, but also their ability to improve their positions by successfully competing in subsequent contests. Thus, as Steger et al. (2004) and Norrander (2006) note, the ability to raise funds in and of itself does not mean that candidates’ will be able to improve their standings, particularly if campaign funds are allocated poorly. Instead, it is candidates who have successfully managed their financial resources that will be in a better position to reach their goals and therefore, will be less likely to terminate their campaigns.Footnote 6

No matter how many candidates are competitive during a campaign, all but one will lose a given nomination contest. As noted earlier, it usually becomes clear fairly early on who will be the party’s eventual nominee (Adkins and Dowdle 2001a, b; Cohen et al. 2008; Steger 2008; Steger et al. 2004). Other candidates can remain competitive in the sense that they attract significant vote shares and win meaningful numbers of delegates, but they will ultimately lose to the frontrunner. As it becomes clearer who will win the nomination, other candidates will be more likely to drop out of the race. The benefit of possibly winning the nomination obviously dwindles as it becomes clear to a candidate that s/he will lose. Moreover, once the outcome of a nomination race is clear, the profile-raising benefit diminishes as elite and voter interest wanes and the party-related costs increase. In light of these considerations, our final hypothesis is that as uncertainty about the outcome of a nomination race fades, all trailing candidates will be more likely to terminate their campaigns.Footnote 7

Data and Methods

To test our hypotheses regarding the length of presidential nomination bids, we collected data on nomination contests from 1980 to 2008. We exclude all the races in which an incumbent president seeks reelection, as these campaigns often are uncontested (i.e., 1996 Democrats; 2004 Republicans) or attract few competitors (i.e., 1980 Democrats; 1992 Republicans).Footnote 8 Thus, we analyze data from eleven nomination campaigns (the 1984, 1988, 1992, 2000, 2004, and 2008 Democratic campaigns and the 1980, 1988, 1996, 2000, and 2008 Republican campaigns).

For these campaigns, we next need to determine which candidates should be included in the analysis. However, as Steger et al. (2004) note, deciding which candidates to include and which to exclude is not straightforward given that dozens of individuals register as a candidate with the Federal Election Commission. For our analysis, we include all candidates who demonstrated a minimal level of support (i.e., a non-zero percent of support) in pre-campaign Gallup or Harris polls and formally contested at least one delegate-determining contest.Footnote 9

The Dependent Variable

For each candidate in our data, we are interested in the length of time s/he stayed in the race before withdrawing. Put differently, we are interested in explaining the timing of these withdrawals. As such, these data should be considered duration data (see Box-Steffensmeier and Jones 2004). A number of our independent variables vary as a campaign progresses and we thus structure our data so that there is an observation of each candidate for each day that they remain in the nomination race. We include a dummy variable noting whether the candidate in question withdrew from the race on that particular day.

A key issue with duration data is identifying the points at which time starts and stops. The starting points of nomination campaigns are not easy to define or observe; a point exacerbated by a lack of consensus in the literature. We use the day after the Iowa caucus as the starting point of our analysis. While candidates actively campaign well in advance of the Iowa caucus, most candidates withdraw at some point after the first contest. Moreover, many of our hypotheses are focused on the events occurring during the delegate gathering phase of the nomination process.Footnote 10 More importantly, this criterion provides a clear demarcation between the unofficial “invisible” or “money” primary, which may extend for years, and the process that actually determines nominees. We do not dispute that important activity occurs during the former phase of the campaign. Ultimately, however, if candidates choose not to contest any of their party’s delegates, it is difficult to argue that they are actually running for the nomination. Thus, excluded from the analysis are any candidates who withdrew prior to Iowa.Footnote 11 This leaves 74 candidates in our data, for a total of 4,532 days at risk of campaign termination.

The point at which the duration of a candidacy ends is easier to identify. We consider a candidacy to have ended when the candidate formally withdraws from the race or suspends his or her campaign. There are candidates who never drop out of the race, including the eventual nominee and losing candidates who choose not to exit the race. We handle these candidates by right-censoring the data at the day after the last primary election.Footnote 12 Duration models are designed to handle right-censored data so this feature of our data should not prove problematic.

We are interested in explaining variation in how long candidates stay in a nomination race and duration models are well-suited for this task. We estimate a semi-parametric Cox model, which makes no assumptions about the nature of the baseline hazard function.Footnote 13 We estimate robust standard errors that allow residuals to be correlated across the multiple observations associated with a given candidate. We also stratify the model by election cycle, which allows each election cycle to have its own baseline hazard function. This stratification should account for election cycle-specific heterogeneity.Footnote 14

To be clear, the Cox model estimates the effect of our independent variables on the hazard rate of a candidate withdrawing from the race on a given day (time t). A hazard rate is analogous to a probability, although it does not have an upper bound. The hazard of a candidate withdrawing from the race is directly linked to length of the candidate’s time spent campaigning for the nomination. As the hazard rate increases, the expected duration of a candidacy decreases.

Independent Variables

Our hypotheses point towards the inclusion of several independent variables in our duration model. Name Recognition is a poll-based measure of the candidate’s level of name recognition at the start of the campaign.Footnote 15 We expect Name Recognition to have a positive coefficient estimate, indicating that it increases the hazard of a candidate withdrawing from the race, all else equal.

To measure Media Coverage, we utilize the Vanderbilt Television News Archive to determine the daily number of network news stories mentioning each candidate in our data. To smooth these data out a bit, we sum the number of stories mentioning a candidate over the previous seven days. For each day in each campaign, we identify the candidate with the largest number of stories over the prior seven days and set Media Coverage at 100 for this candidate. For all the other candidates in the race, Media Coverage equals the number of stories mentioning the candidate (over the past seven days) divided by the number of stories for the most-covered candidate (then multiplied by 100 to make this a percentage). Media Coverage is thus a measure of a candidate’s relative amount of media coverage over the prior week.Footnote 16 This variable should have a negative coefficient.

Measuring how connected a candidate is to his or her party is less straightforward. We begin by coding whether a candidate has served as a member of Congress (Member of Congress) or has held another major political office such as governor or cabinet head (Other Major Office).Footnote 17 We assume that candidates falling into either of these categories are, on average, more connected to their party than candidates who do not. The coefficient estimate for each of these dummy variables should be positive, indicating that these candidates with tighter connections to their parties should have a higher risk of dropping out of the race on a given day, all else equal.

For candidates who have served in Congress, we have additional information on how close they are to their party. Utilizing first-dimension Common Space scores (Poole 1998), we calculate how many standard deviations away a candidate is from the relevant party mean (including all party members in both chambers) in the election year in question. Candidates with a greater Ideological Deviation from their fellow partisans in Congress can be considered as being less connected to the party mainstream and thus we expect the estimate for this variable to be negative in direction.

For a candidate who has not served in Congress but has been elected governor, we utilize the Common Space scores for the relevant state’s congressional delegation to predict a score for the candidate (see Steger 2008). Appendix 1 details this measurement strategy. For a candidate who has not served in Congress, but has held a cabinet position, we use the Common Space score for the appointing president.Footnote 18 As above, we use these predicted Common Space scores to determine a candidate’s Ideological Deviation from fellow partisans in Congress.Footnote 19

To measure how well a candidate has faired in electoral contests at a given point in time, we utilize the results from the most recent primary election and subtract the candidate’s percentage of the vote from the winner’s percentage. If more than one primary election were held on a given day, we average the results. We also include Iowa caucus first round results in this measure. Other caucuses are not included.Footnote 20 We use the distance measure instead of raw election results because it provides a better gauge as to how the candidate performed. Winning 20% of the vote is impressive if it is the highest vote total (and thus Contest Distance equals zero) but is unimpressive if the winner won 60%. We expect that as Contest Distance increases, the hazard of withdrawing will increase. It is important to point out that the value this variable takes on will change over time for a given candidate.Footnote 21 Akin to Haynes et al. (2004), we measure Delegate Count Distance as the percentage of the allocated delegates the candidate in question has won through time t (as reported by CQ Weekly Reports) and subtract it from the percentage won by the candidate with the most delegates. The greater Delegate Count Distance, the more likely it is that the candidate will exit the race.

We also include several independent variables that are prospective indicators of competitiveness. Field Size should increase the hazard of terminating a candidacy and is simply the number of candidates in the race at time t. Poll Distance is generated in the same manner as Contest Distance, except here we use the most recent national poll results (Gallup or Harris).Footnote 22 Again, this variable will change over time for a candidate as his or her poll standing (and that of the leader) changes. We expect these variables to have positive coefficient estimates.

To measure Cash on Hand, we start by determining a candidate’s cash on hand at the start of the month under analysis, as reported to the Federal Election Commission. We then identify the candidate in the race with the largest amount of cash on hand for that time period. Cash on Hand equals a candidate’s cash on hand divided by the largest amount of cash on hand at that point in time (multiplied by 100 to make this a percentage).Footnote 23 Thus, if the candidate with the largest amount of cash on hand has five million dollars, a candidate with two million dollars has a Cash on Hand of 40. The candidate with the largest amount of cash on hand has a value of 100 for this variable. As this variable increases, we expect the hazard of a candidate withdrawing to decrease (i.e., we expect a negative coefficient).

Certainty of Losing is the log of the percentage of the delegates needed to secure the nomination that has been won by the candidate who is the delegate leader.Footnote 24 This variable equals zero for candidates who are leading in the delegate count, as they are not at all certain that they will lose. Certainty of Losing should have a positive coefficient. The clearer it is that candidates are not the nomination the more likely they are to withdraw. Note that this variable captures the influence of frontloading on candidates’ exit decisions (e.g., Mayer and Busch 2004). For earlier, less frontloaded races in the dataset, this variable increases at a much slower rate; reflecting the greater spacing between individual contests over time and thus, the longer time period required for the frontrunner to accrue the requisite delegates. For more recent campaigns, where frontloading has been heightened, Certainty of Losing increases more rapidly due to the greater number of individual contests early in the process that allow the frontrunner to more quickly obtain the delegates necessary to secure the nomination.

Results

The results of our initial estimation of the stratified Cox model (Model 1) are reported in the first column of Table 1. The independent variables are jointly significant in the statistical sense and most are individually significant.Footnote 25 Given the manner in which Cox models are parameterized, a positive coefficient estimate indicates that an independent variable increases the hazard of a candidate ending their candidacy at time t. Since the duration of a campaign is inversely related to the hazard of a candidate withdrawing on a given day, a positive coefficient indicates that an independent variable decreases the expected duration of a candidacy.

Turning to the parameter estimates of interest, we argue that candidates will stay in the race longer if they have more to gain in terms of raising their profile. The coefficient estimate for Name Recognition in Model 1 is in the direction we hypothesize and is statistically significant. A candidate’s initial level of name recognition has a positive effect on the hazard of that candidate withdrawing at time t. Candidates with lower levels of name recognition are less likely to drop out on a given day and thus have longer candidacies, all else equal. It appears that candidates are motivated to stay in the race by the possibility of increasing their profile, with an eye towards improving their future political role or career. However, the estimate for Media Coverage is neither statistically significant nor in the expected direction.Footnote 26 Thus, while a candidate’s initial level of name recognition affects how long they remain in the race, recent media coverage of the candidate does not decrease his or her likelihood of withdrawing.

We also contend that candidates vary in how much they care whether staying in the race for a lengthy period of time causes any potential harm to their reputation within the party or eventual nominee’s success in the general election. The results of Model 1 are consistent with our theoretical expectations as it appears that candidates who are connected to their party terminate their campaigns more quickly than those less connected to their party’s mainstream. The positive and statistically significant estimates for Member of Congress and Other Major Office reveal that candidates who have held significant political positions have a greater hazard of exiting the race at time t than candidates who have not held any sort of major office and are thus presumably less connected to the party.

In addition, the result for Ideological Deviation indicates that candidates who deviate from their party’s mean ideological position in Congress are less likely to drop out at time t than candidates who are in the ideological mainstream of the party. As we argue above, this is the case because it is less costly for party outsiders to engage in lengthy, losing candidacies than it is for party insiders. Steger (2008) finds that ideologically extreme candidates get more primary election votes than would otherwise be expected. Our results suggest that these candidates also stay in the race longer, even once any competitive advantages are controlled for.

Turning next to the variables assessing the influence of competitiveness on candidacy duration, the results of Model 1 provide little initial support for the importance of retrospective indicators of competitiveness in shaping a candidate’s decision to remain in the race or withdraw. The estimates for Contest Distance and Delegate Count Distance are in the predicted direction (positive), but are not statistically significant.Footnote 27 It thus appears that recent electoral results and the allocation of delegates have surprisingly little influence on the decision to exit from a presidential nomination campaign. Below, we revisit the result for Contest Distance.

The results for Field Size and Poll Distance suggest that prospective evaluations of future competitiveness do influence a candidate’s decision to remain in the race. Consistent with Aldrich (1980), the larger the Field Size at time t the shorter the length of time the candidate will stay in the race, all else equal. The estimate for Poll Distance reveals that the further behind the leader a candidate is, the more likely it is that s/he will drop out of the nomination contest. Cash on Hand, however, does not exert a significant effect. This interesting result (one that we further discuss below) implies that being successful in raising money does not translate into longer candidacies, once other indicators of competitiveness and candidate motivation are controlled for in the model.Footnote 28

Not surprisingly, Certainty of Losing has a positive and significant coefficient estimate, revealing that as it becomes increasingly clear that trailing candidates will not ultimately win the nomination they become more likely to drop out. This result, in conjunction with the insignificant estimate for Delegate Count Distance, implies that candidates care about how close the frontrunner is to securing the nomination, not how far behind the frontrunner they are in the delegate totals. This result is compatible with Norrander’s (2000) conclusion that the competition for a nomination ends once the frontrunner has won a substantial proportion of the necessary delegates. This result also subsumes the commonly made argument that frontloading shortens the length of candidacies during the nomination phase of an election year. In a front-loaded campaign, the eventual losers become more quickly aware of their fates.

Reconsidering Contest Distance

One conventional wisdom regarding nomination campaigns is that the Iowa caucus and New Hampshire primary play a disproportionate role in determining nomination outcomes and the length of campaigns (e.g., Adkins and Dowdle 2001a; Steger et al. 2004). To test whether these two specific electoral contests might affect the decision to withdraw from the race, we estimated our model a second time including two interaction terms. The first consists of Contest Distance and a dummy variable indicating whether the most recent contest in question is the Iowa caucuses (Iowa). The second consists of Contest Distance and a dummy variable indicating whether the most recent contest is the New Hampshire primary (New Hampshire). These interaction terms allow us to assess whether these two events play a role in determining whether candidates drop out, even though Contest Distance generally does not appear to influence this decision.Footnote 29

The results from this model estimation (Model 2) are reported in the second column of Table 1. The coefficient estimates for the two interaction terms are positive and statistically significant, indicating that the results of the Iowa caucus and New Hampshire primary influence the decision to remain in the race or withdraw. While Contest Distance generally does not have any influence on candidacy duration, the results of these two specific contests do affect candidacy duration. The worse that a candidate does in either of these contests, as compared to the winner, the more likely it is that this candidate will withdraw from the race. The substantive inferences for the other independent variables are the same as in Model 1.

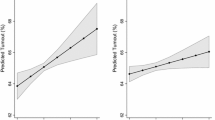

To get a better substantive feel for these effects, we generate predicted hazard rates for candidates dropping out of the race. Figure 1 presents predicted hazards (using Model 2) on the y-axis while Contest Distance varies on the x-axis. Three curves are plotted: the first for hazards when Iowa equals one (i.e., the most recent contest result is that of the Iowa caucus), the second for hazards when New Hampshire equals one (i.e., the most recent contest result is that of the New Hampshire primary), and the third for hazards when both these dummy variables equal zero (the most recent contest result is from a subsequent primary). For the Iowa hazards, the baseline hazard is set to its mean value for the week after this caucus. For the New Hampshire hazards, the baseline hazard is set to its mean value for the week after this primary. For the Other Contests hazards, the baseline hazard is set to its mean value for all other campaign days.Footnote 30

Effect of Contest Distance on the hazard of withdrawing from the race. Note: All other independent variables are held at their mean values. For the Iowa hazards, the baseline hazard is set to its mean value for the week after this caucus. For the New Hampshire hazards, the baseline hazard is set to its mean value for the week after this primary. For the Other Contests hazards, the baseline hazard is set to its mean value for all other days

The plotted hazards associated with days following the post-New Hampshire contests (the Other Contests hazards) show that candidates are generally more likely to drop out after these subsequent primaries. However, the results of these later contests do not appear to affect the hazard of withdrawing (the hazards appear to decrease slightly as Contest Distance increases, but based on the insignificant coefficient estimate for this variable we cannot conclude that this slope is truly negative). In contrast, the worse a candidate does in the Iowa caucus or New Hampshire primary, the greater the hazard of withdrawing from the race. The relatively flat curve for the Iowa caucus results, however, suggests that candidates’ performances in Iowa relative to the winner do not exert much of a substantive effect on the exit decision despite the statistically significant coefficient for the Contest Distance × Iowa interaction. The steep increase in the hazard for the New Hampshire primary indicates that candidates’ performances in the Granite State have strong substantive effects on their hazard of withdrawing from the race.

Similarly, we can more clearly assess the substantive effects for party-related costs by generating predicted hazard rates (from Model 2) for candidates dropping out of the race as a function of variation in party connectedness and Ideological Deviation (implicitly conditioned by whether we have a measure of this variable for the candidate). Figure 2 plots three sets of hazard rates: one for candidates who served in Congress, one for candidates who have served in another major office, and one for candidates who have never held any kind of major office. The full observed range of Ideological Deviation is plotted on the x-axis.Footnote 31 As discussed above, Ideological Deviation does not vary for candidates who never held a major office and the hazards for this candidate type are therefore flat.

This figure reveals that those who have not held elective office (i.e., party outsiders) generally have low likelihoods of dropping out on a given day, all else equal. In contrast, candidates who have held office typically have a greater hazard of withdrawing from the race; reflecting the greater party related costs that these candidates may face for continuing an unsuccessful bid for their party’s nomination. At the same time, this effect is not constant. Rather, Ideological Deviation exerts a negative effect on the hazard rates for office holders. Indeed, office-holding candidates who are ideological outliers appear to have very similar hazards to those who have never held major office.

The Role of Money

While the results presented above are largely consistent with our theoretical expectations, these results diverge from some of the conventional wisdom regarding nomination campaigns, as well as the findings of prior research on the winnowing process. For instance, in her analysis of the length of time that candidates remain in the race for a nomination, Norrander (2006) focuses on the role of money and finds that it has a quadratic relationship with the length of candidacies. Well-funded and poorly funded candidates stay in the race for a long time while moderately funded candidates exit earlier. We find that cash reserves do not exert a simple linear effect on the duration of a candidacy, but have we misspecified our model in this respect?

We suspect the answer is no. Norrander’s results are likely a function of party outsiders often being poorly funded and, as we argue, less likely to drop out early since lengthy losing candidacies are less costly to them. Similarly, candidates with low levels of name recognition stay in the race longer, and are probably less successful in raising money. Since we account for the degree to which a candidate is connected to his or her party as well as name recognition, it seems there is little reason to expect money to exert a curvilinear effect. Nonetheless, we also estimated our model while including the square of Cash on Hand. Under this specification the estimates for both Cash on Hand and its square are statistically insignificant, supporting our suspicion that once profile-raising benefits and party-related costs are controlled for money should not exert a curvilinear effect on the hazard of withdrawing from the race.

The null finding regarding the role of campaign money is interesting in its own right, given the importance typically attached to fundraising. We are certainly not willing to go so far as to conclude that money is irrelevant to nomination campaigns. Indeed, one reason for our results may be that for many candidates fundraising, poll standings, and electoral performance are closely intertwined (Damore 1997). Thus, while candidates’ ability to raise money may be a precursor to other factors shaping candidates’ decision making, fundraising in and of itself may not directly influence how long a candidate remains active in a nomination campaign, all else equal (also see Cohen et al. 2008).Footnote 32

Is the Duration of a Candidacy Determined Before the Iowa Caucus?

Recent research (e.g., Adkins and Dowdle 2001b; Cohen et al. 2008; Steger 2008) suggests that activity during the invisible primary has significant effects on determining the winners and losers of presidential nomination campaigns. Does the same hold for the exit process? While our model does include a time-constant component (e.g., candidate characteristics indicating connection to the party), our argument regarding perceptions of competitiveness and the certainty of losing the nomination points towards a more dynamic (or time-varying, to use duration terminology) view of nomination campaigns. We find that the duration of a candidacy is explained by several variables that change in value as the campaign progresses. Specifically, Field Size, Poll Distance, and Certainty of Losing are all time varying and are all significant predictors of the length of a candidacy. In light of the performance of these variables, it appears that what occurs during the delegate-allocating phase of the nomination process plays a significant role in the length of time that candidates remain active. Or put differently, how long candidates choose to contest their party’s nomination is not determined by what occurs prior to the Iowa caucuses.

There is, however, the possibility that variation in Poll Distance and Field Size across candidates and election cycles, respectively, explains the hazard of exiting the race. In other words, it could be the case that the static components of these two variables have the explanatory power, not the dynamic components that change over time for a given candidate. To test this possibility, we estimated our model with two additional independent variables that do not vary over the course of a campaign: Initial Poll Distance and Initial Field Size at the time of the Iowa caucus. With these controls in place, the estimates for Poll Distance and Field Size remain statistically significant. These results indicate that static components of these two variables are not driving the coefficient estimates. The expected duration of a candidacy changes from day-to-day in a dynamic manner, instead of being fixed at the start of the campaign.

Conclusion

The purpose of this research is to explain candidates’ decisions to drop out of U.S. presidential nomination contests. The three components of our argument are that the decision to remain in the race or withdraw is a function of the mix of two motivations (winning the nomination and profile-raising), the degree to which a candidate is connected to his or her party, and assessments of competitiveness. The results of our duration analysis of presidential nomination campaigns from 1980 to 2008 are largely consistent with our argument as we find that the decisions of presidential aspirants to continue or terminate their candidacies are shaped by the desire to raise their profiles, the potential party costs they may face for continuing a campaign after the eventual nominee has emerged, and by prospective and retrospective indicators of their competitiveness. Our results, however, provide no support for the role of cash on hand or media coverage in affecting candidates’ decision to continue or end their campaigns.

Although the winnowing process is central to our understanding of presidential nomination campaigns, the relative dearth of prior systematic research on this phenomenon is surprising. Building upon prior scholarship, we have sought to move our understanding of this process forward on a number of fronts. Empirically, we see two notable contributions from our effort. First, by utilizing data from eleven campaigns, including 2008, we are able to develop a more general understanding of the factors underlying candidates’ exit decisions. Second and as noted above, we develop a dynamic theoretical framework that allows candidates’ prospective and retrospective evaluations of their competitive standing vis-à-vis their opponents to be continually updated over the course of a campaign and consistent with Haynes et al. (2004) and Norrander (2006), we evaluate these hypotheses using dynamic statistical techniques.

Perhaps more importantly, we have sought to capture the multiple motivations that underlie presidential candidacies and explain how this goal seeking behavior is tempered by the dynamics of the nomination process and the value that candidates attach to their reputations within their parties. To be sure, many of these considerations have been suggested by prior research (e.g., Norrander 2006; Steger et al. 2004), but we refine these arguments and develop more objective and precise indicators of candidates’ pre-campaign profiles than the fairly blunt candidate classifications previously used (i.e., big shots versus long shots, careerists versus advocacy, or traditional versus non-traditional). Our results suggest that the motivations underlying a candidacy affect the decision to remain active in a nomination campaign. The degree to which candidates are tied to their party also plays an important role in determining candidacy duration.

Ultimately, our analysis provides a mix of good and bad news for those concerned with the process by which presidential nominees are selected. One common lament is that the outcome of the nomination process is largely predetermined by party elites and other “policy demanders” prior to the delegate allocating phase (Cohen et al. 2008). As a consequence, in most campaigns, the pre-Iowa frontrunner goes on to win the nomination (Adkins and Dowdle 2000, 2001a, b; Cohen et al. 2008). With respect to this concern, our results indicate that many candidates behave as if the outcome of the campaign is not predetermined and instead, respond to the ongoing dynamics of the campaign. More to the point, one of the novel components of our argument and analysis involves the level of certainty that a candidate has that someone else will become the party’s nominee. We treat this level of certainty as varying over the campaign and our results indicate that this variable has an important effect on the decision to withdraw from the race. In addition, our results suggest that the winnowing process is driven more by national public opinion than by campaign resources. It appears that candidates are more likely to stay in the race when they are currently polling well, regardless of their available resources or how well they polled before the Iowa caucus.

Another potentially positive implication of our analyses is of an informational nature. Candidates who are not well-known at the start of the campaign tend to stay in the race longer. These lengthier candidacies presumably provide voters, activists, fellow politicians, and the media a better opportunity to learn about these candidates. This information may or may not be particularly useful at the time, but candidates who are able to use nomination campaigns to raise their profiles are likely to play significant political and policy making roles in the future.

The potential bad news is that there is a bias to the winnowing process that may be less than ideal. Candidates closely connected to their party drop out more quickly than those who are party outsiders. Thus, voters in states with later contests may end up choosing from a field in which there are a few insurgent-style candidates and only one candidate (the frontrunner) from their party’s mainstream. Moreover, given the effect of our Certainty of Losing variable, it appears that frontloading only works to exacerbate these dynamics.

Notes

The post-reform era describes the nomination process beginning in 1972 after the implementation of the McGovern–Frazer Commission guidelines that sought to take control of the nomination process away from party bosses and put it in the hands of the party rank and file. The significance of these reforms is that candidates were now obligated to contest the various state party caucuses and primaries to accrue the requisite delegates needed to win the nomination (see Polsby 1983 for an extended discussion).

The exception to this statement is the treatment of “issue” or “advocacy” candidates. Some models of nomination processes (e.g., Steger et al. 2004) allow for the possibility that some candidates are involved in nomination campaigns in an effort to raise their national profile and draw attention to specific issues.

Scholarly work on the effect of divisive primaries on general election outcomes yields mixed results. Kenney and Rice (1987) and Lengle et al. (1995) find evidence that a divisive primary hurts the eventual nominee’s performance in the general election while Atkeson (1998) and Stone et al. (1992) find that divisive primaries have little effect if any. To some extent, it does not matter what the data indicate. What is significant is that political elites believe that such an effect exists (see Kenney and Rice 1987).

See Bartels (1988) for an in-depth discussion of the role of momentum in presidential nomination contests.

Aldrich (1980, p. 113) raises the importance of field size in presidential nomination contests by suggesting that the “greater the number of active candidates at the outset, the greater the instability. The more candidates there are, the greater the role of the dynamics of the primary and caucus system in reducing the number of candidates”.

Prior research suggests that candidates’ ability to raise and maintain adequate cash reserves is highly correlated with other variables in our model such as poll standing, candidate characteristics, and likelihood of winning the nomination (e.g., Aldrich 1980; Damore 1997; Haynes et al. 2004). We return to this point below.

The logic underlying this hypothesis is consistent with research examining the consequences of frontloading on the dynamics of nomination campaigns. For example, Mayer and Busch (2004) argue that frontloading causes nominees to effectively capture the nomination after only a few contests. Thus, because the frontloading of primaries increases the speed at which the winner of a nomination campaign is determined, frontloading causes uncertainty about the eventual outcome to more quickly dissipate. This hypothesis also harks back to some of the seminal presidential nomination campaign research that tended to highlight the instability and uncertainty stemming from the dynamic nature of nomination campaigns (e.g., Aldrich 1980; Bartels 1988). In contrast, more recent work emphasizes the stability and predictability of the outcomes of recent post-reform campaigns (e.g., Adkins and Dowdle 2001a, b; Cohen et al. 2008; Steger et al. 2004).

While the 1980 Democratic and 1992 Republican campaigns did feature spirited challenges to sitting presidents, the dynamics of these races are different from campaigns not featuring incumbents (Aldrich 1980) and thus are excluded from the analysis presented here.

The candidates included in our analysis are: 1980 (R)—Anderson, Baker, Bush, Connally, Crane, Dole, Reagan; 1984 (D)—Askew, Babbitt, Cranston, Glenn, Hart, Hollings, Jackson, McGovern, Mondale; 1988 (D)—Dukakis, Gephardt, Gore, Hart, Jackson, Simon; 1988 (R)—Bush, Dole, DuPont, Haig, Kemp, Robertson; 1992 (D)—Brown, Clinton, Harkin, Kerrey, Tsongas; 1996 (R)—Alexander, Buchanan, Dole, Dornan, Forbes, Gramm, Keyes, Lugar, Taylor; 2000 (D)—Bradley, Gore; 2000 (R)—Bauer, Bush, Forbes, Hatch, Keyes, McCain; 2004 (D)—Clark, Dean, Edwards, Gephardt, Kerry, Kucinich, Lieberman, Sharpton; 2008 (D)—Biden, Clinton, Dodd, Edwards, Gravel, Kucinich, Obama, Richardson; 2008 (R)—Giuliani, Huckabee, Hunter, Keyes, McCain, Paul, Romney, Thompson.

For instance, it is not clear how to handle variables such as Contest Distance and Delegate Distance if we included time before the Iowa caucus in our analysis.

This decision means that we cannot draw inferences from our analysis regarding the behavior of candidates who withdraw before the Iowa caucus. Presumably the candidates who do not drop out before Iowa are not representative of those who do. Nevertheless, it should be emphasized that most candidates do not drop out before Iowa and thus our conclusions account for the behavior of most candidates.

For the 2000 Democratic nomination campaign, observations for Al Gore are right-censored on the day that his one competitor (Bradley) dropped out. From this point on, it is not reasonable to assume that there is a non-zero hazard of Gore dropping out of the race.

See Box-Steffensmeier and Jones (2004) for an overview of duration models, including the Cox model.

AIC and BIC statistics indicate a clear improvement in model fit when the Cox model is stratified.

Specifically, we use Gallup poll results for the question “have you heard something about” a given candidate. When this question is asked multiple times during the pre-primary phase, we use the earliest poll results. 10 of our 74 candidates were not included in these polls. Seven of these 10 candidates are in the 2008 data. For most of these candidates, we used the average level of name recognition for candidates who served in the same level of office. For Dodd in 2008, for example, we use the average name recognition for the senators in our data. For Keyes in 2000 and 2008 we use his name recognition in 1996. For Taylor in 1996, we use the lowest value of name recognition found in our data. Given that most of these imputed values occur in the 2008 cycle, we estimated our model without the 2008 data and find that the estimate (and standard error) for Name Recognition is very stable, implying that the imputation of missing values does not affect the results for this variable.

It might be useful to consider the substantive content of these news stories (e.g., whether they provide positive or negative coverage of the candidate or focus on policy versus the horse race) but it is not feasible to content analyze all the news stories for the eleven election cycles analyzed here (there are more than 10,000 mentions of candidates in network news stories during the nomination contests included in our analysis). Haynes et al. (2004) perform this type of content analysis, but their data is limited to the 2000 Republican campaign.

Of the 74 candidates in our data, 48 (64.9%) had been members of Congress, 12 (16.2%) had held another major office (such as governor), and 14 (18.9%) had never held any type of significant office.

It should be safe to assume that cabinet appointees, on average, will reflect the ideological orientation of the president. There will be some measurement error associated with this approach, though. Is there a systematic bias introduced by this measurement error? The typical approach used to test whether predicted or imputed values for a variable introduce a bias is to include a dummy variable in the model indicating that the observation has an imputed value for the variable in question. Other Major Office is exactly this sort of variable. It equals one for all candidates for whom we have predicted a Common Space score. Any systematic bias introduced by the imputation will be corrected by the inclusion of this variable.

For candidates who never served in Congress or held a major office, Ideological Deviation is set at zero as we are not confident that we can properly place them on the Common Space scale. The selection of zero is inconsequential because the Member of Congress and Other Major Office dummy variables differentiate observations in which Ideological Deviation equals zero for candidates who are perfectly in-line with their party’s mean from observations in which Ideological Deviation equals zero for candidates for whom we have no basis for measuring their ideological position (e.g., those who have never held elective or appointive office). If we select different values of Ideological Deviation for the candidates for whom Member of Congress and Other Major Office equal zero, the results of our model estimation are unaffected.

An alterative approach would be to use Cohen et al.’s (2008) expert assessments of the ideological location of these non-office holders (which forces us to exclude the non-office holders of the 2008 campaign since they are not included in Cohen et al.’s data). We re-oriented Cohen et al.’s scale to match that of the Common Space scores and multiplied the scores (which range from −1 to 1) by .849 to ensure that the most ideologically extreme candidates (those at either 1 or −1) were equivalent to the most ideologically extreme member of Congress during this time period. We then generated Ideological Deviation for these candidates and re-estimated our models. In both models, the estimate for Ideological Deviation remains negative and significant. The estimates for Member of Congress and Other Major Office decrease in size but remain positive in direction. They are no longer statistically significant, but that is to be expected given that with this specification Ideological Deviation now captures the fact that non-office holders typically deviate more from the center of their party. In sum, using this alternative measurement strategy leads to the same inference—the less connected a candidate is to his or her party the less likely they are to drop out of the race on a given day.

Caucuses provide more ambiguous signals about a candidate’s competitiveness given the multi-stage nature of these processes. Delegates selected by caucuses are included in our measure of Delegate Count Distance.

For data on primary and caucus results, as well as delegate totals, we primarily rely on CQ Weekly Reports.

We utilize Gallup and Harris polls in which the sample is limited to people who identify themselves as being a member of the party in question or who identify themselves as being independents.

We standardize this variable by the maximum amount of cash on hand in order to account for differences in the amounts of money involved in primary campaigns across the election cycles included in our analysis. Norrander (2006) adopts the same approach.

We log this variable with the assumption that a one-unit change in this variable at its low range will matter more than a one-unit change when the frontrunner has almost won the necessary amount of delegates.

A number of scholars argue that ideological heterogeneity in the Democratic Party and the party’s tendency to award delegates in a more proportional manner causes Democratic nomination campaigns to be longer and more contentious as compared to Republican nomination campaigns (Ansolabehere and King 1990; David and Ceaser 1980; Kamarck and Goldstein 1994). To assess whether it is appropriate to pool together Democratic and Republican candidates into a single model, we performed a Chow test which involved interacting all the independent variables with a dummy variable indicating whether the candidate is a Democrat and then including all of these interactions in our model. None of these interaction terms had a statistically significant coefficient. Moreover, a Wald test of the entire set of interaction terms leads us to fail to reject the null hypothesis that the interaction terms have no explanatory power (p = .72). These results provide compelling evidence that it is appropriate to pool the Democratic and Republican candidates together into a single model. Also, note that these null results for the party difference hypothesis are consistent with Norrander (2006). As such, it appears that Republican also-rans behave no differently than their Democratic counterparts when deciding whether to terminate or continue their candidacies; a conclusion that contrasts with recent work (Cohen et al. 2008; Steger 2008) suggesting that the Republican Party is more likely than the Democratic Party to coalesce around a favorite. Thus, while there may be party asymmetries with respect to establishing frontrunners, similar inter-party dynamics do not appear to affect the exit calculus.

This null result remains if we interact Media Coverage with Name Recognition. Even candidates with low levels of name recognition do not appear to consider media coverage when deciding whether to withdraw from the race.

The result for Contest Distance is sensitive to the inclusion of the 2008 candidates. If these candidates are excluded, the estimate for Contest Distance is positive and statistically significant and the interaction terms involving Iowa and New Hampshire are insignificant. None of the other results are similarly sensitive.

This null result remains if we include a candidate’s relative amount of fundraising (i.e., receipts during that time period) in addition to or instead of Cash on Hand. We also considered the possibility that it is the change in the amount of money a candidate has that matters. For each candidate, we calculated the percentage change in the amount of cash on hand from the prior month to the month in question. Again, the resulting estimate indicates that fundraising success does not cause candidates to extend their candidacies.

We do not need to include Iowa and New Hampshire separately in the model because these “main effects” are absorbed into the election cycle-specific baseline hazard.

All other independent variables are set at their means.

All other independent variables and the baseline hazard are held at their means.

The possibility that there are relationships between our independent variables (including Cash on Hand) does not lead to endogeneity concerns, at least in the traditional version of endogeneity (in which an independent variable correlates with the error term) that causes coefficient bias. That said, it is worth considering the relationship between the independent variables. Cash on Hand correlates with Poll Distance, Contest Distance, and Name Recognition. Temporally speaking, Name Recognition (as we measure it) precedes Cash on Hand. Cash on Hand generally precedes Poll Distance and Contest Distance. However, we cannot test, with any level of rigor, what the causal relationships are between these variables. If we had daily data on Cash on Hand (instead of monthly) and more frequent polls (a particular problem in the earlier campaigns) we could attempt to determine Granger causality amongst these variables. Unfortunately, the data are not sufficiently fine-grained to perform this type of analysis. We can prevent Cash on Hand from varying over the campaign (holding it fixed at its value on January 1 of election year). This guarantees that Cash on Hand is not influenced by subsequent polls and electoral outcomes (i.e., makes it relatively exogenous to these other independent variables). When we take this approach, the estimate for Cash on Hand is still insignificant.

References

Adkins, R. E., & Dowdle, A. J. (2000). Break out the mint juleps? Is New Hampshire the ‘primary’ culprit limiting presidential nomination forecasts? American Politics Quarterly, 28(2), 251–269.

Adkins, R. R., & Dowdle, A. J. (2001a). How important are Iowa and New Hampshire to winning post-reform presidential nominations? Political Research Quarterly, 54(2), 431–444.

Adkins, R. R., & Dowdle, A. J. (2001b). Is the exhibition season becoming more important to forecasting presidential nominations? American Politics Research, 29(3), 283–288.

Aldrich, J. A. (1980). Before the convention. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ansolabehere, S., & King, G. (1990). Measuring the consequences of delegate selection rules in presidential nominations. Journal of Politics, 52(2), 609–621.

Atkeson, L. R. (1998). Divisive primaries and general election outcomes: Another look at presidential campaigns. American Journal of Political Science, 42(1), 256–271.

Bartels, L. M. (1988). Presidential primaries and the dynamics of public choice. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Box-Steffensmeier, J. M., & Jones, B. (2004). Event history modeling: A guide for social scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cohen, M., Karol, D., Noel, H., & Zaller, J. (2008). The party decides. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Damore, D. F. (1997). A dynamic model of candidate fundraising: The case of presidential nomination campaigns. Political Research Quarterly, 50(2), 343–364.

David, P. T., & Ceaser, J. W. (1980). Proportional representation in presidential nominating politics. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

Gurian, P.-H. (1986). Resource allocation strategies in presidential nomination campaigns. American Journal of Political Science, 30(4), 802–821.

Haynes, A. A., Gurian, P.-H., Crespin, M. H., & Zorn, C. (2004). The calculus of concession: Media coverage and the dynamics of winnowing in presidential nominations. American Politics Research, 32(3), 310–337.

Haynes, A. A., Gurian, P.-H., & Nichols, S. (1997). The role of candidate spending in presidential nomination campaigns. Journal of Politics, 59(1), 213–225.

Kamarck, E. C., & Goldstein, K. M. (1994). The rules do matter: Post-reform presidential nominating politics. In L. Sandy Maisel (Ed.), The parties respond (2nd ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview.

Kenney, P. J., & Rice, T. W. (1987). The relationship between divisive primaries and general election outcomes. American Journal of Political Science, 31(1), 31–44.

Lengle, J. I., Owen, D., & Sonner, M. W. (1995). Divisive nominating mechanisms and Democratic Party electoral prospects. Journal of Politics, 57(2), 370–383.

Matthews, D. R. (1978). ‘Winnowing’: The news media and the 1976 presidential nomination. In J. D. Barber (Ed.), Race for the presidency: The media and the nomination process. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Mayer, W. G., & Busch, A. E. (2004). The front-loading problem in presidential nominations. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Norrander, B. (2000). The end game in post-reform presidential nominations. Journal of Politics, 62(4), 999–1013.

Norrander, B. (2006). The attrition game: Initial resources, initial contests and the exit of candidates during the U.S. presidential primary season. British Journal of Political Science, 36(3), 487–507.

Polsby, N. W. (1983). Consequences of party reform. New York: Oxford University Press.

Poole, K. T. (1998). Recovering a basic space from a set of issue scales. American Journal of Political Science, 42(3), 954–993.

Steger, W. P. (2008). Forecasting the presidential primary vote: Viability, ideology, and momentum. International Journal of Forecasting, 24(April–June), 193–208.

Steger, W. P., Dowdle, A. J., & Adkins, R. R. (2004). The New Hampshire effect in presidential nominations. Political Research Quarterly, 57(3), 375–390.

Steger, W. P., Hickman, J., & Yohn, K. (2002). Candidate competitiveness and attrition in presidential primaries, 1912–2000. American Politics Research, 30(5), 528–554.

Stone, W. J., Atkeson, L. R., Rapoport., R. B., & Ronald, B. (1992). Turning on or turning off? Mobilization and demobilization effects of participation in presidential nomination campaigns. American Journal of Political Science, 36(3), 665–691.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1: Predicting Common Space Scores for Governors

Appendix 1: Predicting Common Space Scores for Governors

In order to determine the degree to which a candidate is in the ideological mainstream of his or her party (Ideological Deviation), we utilize Common Space scores. We need to generate these scores for the candidates who have served as a governor, instead of as a member of Congress (see Steger 2008). We make the assumption that politicians elected to statewide office reflect the policy preferences of their party within the state, as well as the state in general. For instance, the ideology for a Democratic governor of Florida should have an ideal point somewhere between that of the average Florida voter and the average Democrat in Florida. To estimate this value, the ideology of the Florida congressional delegation should provide useful information about both central tendencies. Specifically, we can utilize the average Common Space score for a member of the Florida delegation at the time the governor was last elected, as well as the average score for the Democratic delegation from Florida at that time.

To assess how good of a job these two types of delegation means do in predicting the ideology of a statewide office holder, we used Common Space data for the 97th through 109th Congresses and regressed the first Common Space dimension for U.S. senators on (1) the average first dimension score for House members who are from the senator’s party and state and (2) the average first dimension score for all House members from the senator’s state. The resulting model explains a remarkable 87% of the variation in senators’ Common Space scores and both coefficient estimates are statistically significant (the estimates are .876 and .195, respectively). We then use these estimates to predict the Common Space scores for the seven candidates in our analysis who have been elected governor. The predicted scores are (from liberal to conservative): Howard Dean (−.506), Jerry Brown (−.444), Michael Dukakis (−.406), Bill Clinton (−.250), Rubin Askew (−.140), Ronald Reagan (.212), and George W. Bush (.424). With these predicted scores we generate our measure of Ideological Deviation, just as we do for candidates who served in Congress.

As a robustness check, we recoded Ideological Deviation to equal zero for all office holders who were not members of Congress and thus have imputed Common Space scores and then estimated our models. In other words, we dropped the imputed scores and allowed Ideological Deviation to vary only for members of Congress. The results of this analysis are very similar to those presented in Table 1. The relevant coefficient estimates (standard errors) in Model 2 are 3.08 (.739) for Congress, −1.03 (.296) for Ideological Deviation, and 2.03 (.675) for Other Major Office.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Damore, D.F., Hansford, T.G. & Barghothi, A.J. Explaining the Decision to Withdraw from a U.S. Presidential Nomination Campaign. Polit Behav 32, 157–180 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-009-9098-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-009-9098-9