Abstract

Aims

The current article provides a brief overview of the criteria for defining disease control in acromegaly.

Methods

This was a retrospective, narrative review of previously published evidence chosen at the author’s discretion along with an illustrative case study from Latin America.

Findings and Conclusions

In the strictest sense, “cure” in acromegaly is defined as complete restoration of normal pulsatile growth hormone secretion, although this is rarely achieved. Rather than “cure”, as such, it is more appropriate to refer to disease control and remission, which is defined mainly in terms of specific biochemical targets (for growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-1) that predict or correlate with symptoms, comorbidities and mortality. However, optimal management of acromegaly goes beyond biochemical control to include control of tumour growth (which may be independent of biochemical control) and comprehensive management of the symptoms and comorbidities typically associated with the disease, as these may not be adequately managed with acromegaly-specific therapy alone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Acromegaly is a disease of excessive growth hormone (GH) secretion and the primary aims of treatment are to control GH secretion or its effects on GH-sensitive tissues, most notably increased insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) secretion [1]. Intrinsically, “cure” in acromegaly should be characterized by complete restoration of normal pulsatile GH secretion, but this is rarely achieved [2]. Thus, it is more appropriate to refer to disease control and remission, which in turn is defined based on specific GH and IGF-1 targets that predict or correlate with symptoms, co-morbidities and mortality [3]. Tumour mass reduction or disappearance is also used in establishing disease remission or control [3]. In surgically treated patients, remission is defined by both the normalization of age-adjusted IGF-1 serum concentrations, a random serum GH below 1 μg/L and/or a glucose-suppressed GH level below 0.4 μg/L. In patients treated with SSAs and/or dopamine agonists, adequate control is defined by the achievement of a normal IGF-1 concentration and a “safe” GH level (see below). In this context, a “safe” GH level alludes to a concentration of the hormone below which the increased mortality is reduced to that seen in the general population [3–6]. However, optimal management of patients with acromegaly extends beyond biochemical control to include factors such as tumor growth and attention to comorbid conditions. The current article summarizes the criteria for defining disease control in acromegaly, with an illustrative case study and a particular focus on issues in Latin America.

Measurement of GH and IGF-1 in acromegaly

Assays for GH and IGF-1 have evolved considerably over the past two decades, from the less specific and sensitive radioimmunoassays (RIAs), to a myriad of commercially available ultrasensitive immunoassays that use more specific monoclonal antibodies, which are capable of detecting much lower hormone concentrations [7, 8]. Several analytical and physiological issues need to be taken into account when using GH and IGF-1 assays in the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with acromegaly. This includes the standard preparation used (the so-called International Reference Preparation or “IRP”), which at present should be the recombinant World Health Organization (WHO) second 95/574 preparation for GH and the recombinant WHO second 02/254 preparation for IGF-1 [7–10]. Other analytical aspects to be considered are the specificities of the monoclonal antibodies and, in the case of IGF-1, the interference from IGF-1-binding proteins [9].

Several physiological and pathological states or conditions influence GH and IGF-1 synthesis and secretion. For instance, GH is secreted in pulses occurring mainly at night; thus, a random measurement is not useful, except when the result is particularly low (less than 0.4 μg/L), which confidently excludes the diagnosis [3]. Furthermore, IGF-1 concentrations decrease with age, reflecting the parallel decline of the somatotropic axis, and thus need to be adjusted accordingly. Ethnogenetic factors may also influence IGF-1 levels and, ideally, normal ranges should be established locally using serum from a significant number of age-stratified healthy individuals [9, 11]. In addition, several conditions can lower IGF-1 levels, including malnutrition, poorly controlled diabetes, and hepatic or renal failure, as well as estrogen therapy and hypothyroidism [9, 11].

Biochemical versus symptom control

Based on meta-analyses, mortality of treated acromegaly patients whose serum GH level is below 2.5 μg/L (measured by RIA) is similar to that seen in the general population [12, 13]. In contrast, a serum GH level greater than 2.5 μg/L confers an increased risk of mortality [12, 13]. A similar pattern is seen for IGF-1 when comparing normal age-adjusted levels versus levels above the age-adjusted normal range [12, 13]. Based on these observations, clinicians treating acromegalic patients are advised to aim for random serum GH <2.5 μg/L measured by RIA (probably <1 μg/L measured by modern sensitive immunoassay) and normal IGF-1 levels, and this represents the current definition of controlled disease or “cure” [2, 3, 12, 13].

Unfortunately, there are patients who meet the above criteria for GH who are still symptomatic, have clear evidence of progression of co-morbidities or who have abnormally elevated IGF-1 [2, 14]. Thus, measured values of IGF-1 and random GH may yield a discrepant prediction of disease stabilization, especially in terms of symptomatic disease [2, 14]. In these cases, the IGF-1 level may provide a better measure of average GH secretion, as it correlates well with signs and symptoms of active disease, such as soft-tissue thickening and insulin insensitivity [2, 14, 15]. Furthermore, IGF-1 seems to be a better predictor of disease control than random GH [2, 15]. Although cumbersome and less practical, whenever random GH values are discrepant, multiple GH sampling during a 2-h period with a mean value <1 μg/L may be used to indicate adequate disease control [16].

Suppression of GH during an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) is of limited value in evaluating disease control in many patients, being helpful only in those who are not receiving any pharmacological treatment, most notably in the postoperative setting [2, 3, 16, 17]. Some evidence also suggests that radiotherapy can exaggerate the discordance between disease activity assessed by IGF-1 and GH suppression during an OGTT (if GH nadir is <2.5 μg/L) [18]. In treatment-naïve, biochemically active patients, discordance appears to be greatest in those with only mildly elevated GH output, leading to a high false negative rate with GH suppression measurement [19]. Increased discordance is also seen at the other extreme in patients with particularly high GH levels [20]. In patients treated with pegvisomant, only IGF-1 remains a reliable marker of disease activity, as GH concentrations remain elevated [3, 16].

Thus, for patients receiving medical treatment with SSAs or dopamine agonists, IGF-1 and random GH measurements together are sufficient for assessment of biochemical response [2, 3]. The IGF-1 level, in particular, can be an important determinant of the need for additional therapy, although results can be influenced by the presence of malnutrition, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, liver function impairment, renal failure, inflammatory diseases and malignancies [9, 11, 21]. Finally, it should be noted that the effects of pharmacological therapies on tumor size may not necessarily be related to biochemical remission, and this may represent an aspect of disease control that deserves separate consideration [3, 22–24].

Tumor shrinkage

Tumor size reduction is an important goal in the management of acromegaly [3, 6]. In the first-line clinical setting, control of both GH secretory activity and tumor growth are required in order to achieve comprehensive therapeutic efficacy [3, 6]. The clinical relevance of tumor shrinkage may be greater in macroadenomas than in microadenomas [24]. The clinical benefits of tumor mass shrinkage include relief of optic chiasm impingement, patient reassurance that the mass is shrinking, and possibly a lowered risk of intratumoral hemorrhage [25]. Such effects have the potential to provide a noticeable beneficial impact on patient quality of life.

In addition to the achievement of biochemical control, some pharmacological therapies can also induce significant tumor shrinkage in patients with acromegaly [24–28]. Tumor shrinkage has been reported in approximately two-thirds of patients treated with long-acting SSAs and one-third of patients treated with dopamine agonists [24, 28]. The SSAs being used today are almost exclusively longer-acting, depot formulations and they seem to provide more benefit in reducing tumor size than the old shorter-acting formulations [24, 29]. The effects on tumor size are especially marked when these agents are used as first-line therapy [29]. In a recent study involving 30 newly diagnosed unselected patients receiving SSA therapy for 24 weeks, 97 % experienced a reduction in tumor volume, 79 % had a reduction ≥20 % and the median reduction in volume was 39 % [30]. In the case of SSAs, the anti-tumor effects may relate, at least in part, to direct effects on cell growth and indirect effects via inhibition of angiogenesis [27]. The available evidence suggests that pegvisomant does not reduce tumor size, at least when used as monotherapy [31]. Earlier concerns regarding pituitary adenoma growth during pegvisomant therapy now seem to have settled to an estimated risk of about 3 % thanks to long-term follow-up studies [32].

Control of comorbidities

Major comorbidities associated with acromegaly include cardiovascular disease (including cardiomyopathy), diabetes, hypertension, sleep apnea, and arthritis [3, 33–36]. Acromegaly is also associated with a greater risk of several neoplasms, particularly colonic polyps and carcinoma, and there is growing evidence that the risk of thyroid tumors is also increased [33, 37–40]. Furthermore, in addition to hypertension and diabetes, active acromegaly is associated with several other classic and nonclassic cardiovascular risk factors, including insulin resistance and dyslipidemia, as well as increased levels of fibrinogen and lipoprotein (a) [41].

Biochemical control has been shown to provide improvements in several comorbidities of acromegaly, especially cardiomyopathy, sleep apnea, and arthralgia, but also hypertension and dyslipidemia [3, 42, 43]. In one study involving 30 patients with newly diagnosed acromegaly, 12 months of SSA therapy decreased joint thickness in all cases, but the reduction was greater in those with controlled disease, among whom 61 % had normalization of shoulder thickening and 89 % had normalization of knee thickening [33]. Similarly, successful biochemical control after 12 months of SSA therapy has been shown to normalize left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy in 100 % and LV ejection fraction in 80 % of patients under 40 years of age (but only 50 % of patients over 40 years of age for either measure) [33]. These results are supported by a meta-analysis of 18 SSA trials, which found a significant reduction in LV mass and several functional hemodynamic parameters [44]. In a recent study, LV mass regression was reported in men (but not women) and there were also significant improvements in arterial stiffness and endothelial function after 24 weeks of SSA therapy [30]. In the same study, 61 % of the 30 patients exhibited an improvement in sleep apnea, but 30 % experienced worsening and 9 % had no change [30]. Thus, effective biochemical control does not always result in effective control of these comorbidities and improvements may be limited, in spite of normalized GH levels [3, 41, 42, 45]. Additional therapies are, therefore, frequently required to treat comorbid conditions in acromegaly. In particular, effective control of diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidemia is essential in order to reduce the increased vascular morbidity and mortality associated with these key cardiovascular risk factors [3, 42]. Fortunately, good glycemic control can be achieved in the majority of acromegalic patients with type 2 diabetes using standard approaches, such as lifestyle intervention, oral glucose-lowering agents and insulin [46]. Hypertension in acromegaly is also easily controlled with standard antihypertensive medications [47]. Regarding dyslipidemia, statin therapy has been shown to provide significant improvements in atherogenic lipid profile and reduce calculated coronary heart disease risk in patients with acromegaly [48].

Case study: Addressing multiple comorbidities in a patient with acromegaly (Lucio Vilar, MD, PhD)

A 40 year-old female was referred to the endocrinologist in April 2008 due to amenorrhea over the previous 10 months |

Symptoms |

Increased shoe size (from 35 to 38) |

Oily skin, excessive sweating |

Excessive snoring |

Amenorrhea (10 months) |

Polyarthralgia |

Signs |

Height: 1.56 m |

Weight: 66.3 kg |

Blood Pressure (BP): 160/100 mmHg |

Enlarged hands and feet |

Macroglossia, diastema |

Prognathism, dental malocclusion |

No goiter |

Personal and family history |

No family history of diabetes, cancer, thyroid disease or pituitary disease |

The last medical evaluation was made in 2004; no biochemical abnormality was found |

Lab tests |

GH (ICMA): 23.8 μg/L |

IGF-1 (ICMA): 960 μg/L (normal 101–267 μg/L) |

GH nadir during OGTT: 6.3 μg/L |

Prolactin and thyroid function tests: normal |

Estradiol: 46 pmol/L (12.6 pg/mL) |

FSH: 0.8 IU/L |

Fasting plasma glucose: 7.6 mmol/L (137 mg/dL) |

HbA1c = 7.4 % |

Serum calcium: normal |

Triglycerides: 5.5 mmol/L (487 mg/dL) |

HDL cholesterol: 0.8 mmol/L (31 mg/dL) |

Diagnosis |

Acromegaly caused by a GH-secreting pituitary macroadenoma |

MRI |

Macroadenoma (2.3 × 1.8 cm), with infrasellar, parasellar and suprasellar extension (Fig. 1) |

Computerized visual field testing ⇒ Normal |

Echocardiogram |

Marked left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy |

No valvular abnormalities |

Treatment |

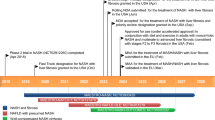

Patient was submitted to transsphenoidal surgery in Sept 2008, which was not curative (Fig. 1) |

IGF-1: 802 μg/L (normal 101–267 μg/L) |

GH: 13.6 μg/L |

GH nadir: 3.7 μg/L |

SSA was started in March 2009, followed by a higher dose in May 2009 followed by SSA + cabergoline 3 mg/week |

IGF-1 response to medical treatment showed improvement to normal range (101–267 μg/L) with sequential medical therapy from 780 μg/L to 253 μg/L |

Thyroid ultrasound |

June 2008: normal |

January 2011: 1.7 cm hypoechoic solid nodule with increased blood flow in right lobe |

FNA biopsy ⇒ Papillary thyroid carcinoma |

March 2011 ⇒ Total thyroidectomy |

Thyroid histology ⇒ BRAF V600E-positive tall cell variant papillary thyroid carcinoma |

Patient’s comorbidities |

Thyroid carcinoma |

Diabetes mellitus |

Dyslipidemia |

Left ventricular hypertrophy |

Polyarthralgias |

Central hypogonadism |

Excessive snoring (sleep apnea?) |

Effect of treatment on comorbidities |

Thyroid carcinoma ⇒ No evidence of disease recurrence or metastasis after total thyroidectomy and 131I abalation therapy |

Diabetes ⇒ Metformin XR (750 mg/d) required to control blood glucose and HbA1c levels |

Dyslipidemia ⇒ resolved with the improvement of diabetes and normalization of GH and IGF-1 levels |

Hypertension ⇒ BP control achieved with losartan + amlodipine + indapamide |

Central hypogonadism/excessive snoring ⇒ resolved with GH/IGF-1 normalization |

LV hypertrophy ⇒ improvement after BP control and hormonal normalization |

Case discussion

This case provides a good example of a patient with a burden of multiple comorbidities typical of acromegaly, including diabetes, dyslipidemia and hypertension (all of which are major cardiovascular risk factors), cardiomyopathy, arthralgia, and sleep apnea, along with thyroid carcinoma. After surgical failure, biochemical control and tumor shrinkage was achieved through the use of pharmacological therapy, which was ultimately successful using a combination of SSA and dopamine agonist [49, 50]. Biochemical control was associated with improvements in some comorbid conditions (e.g., excessive snoring/sleep apnea) and may have contributed to amelioration of dyslipidemia and cardiomyopathy. However, appropriate specific therapies for diabetes (metformin), hypertension (losartan/amlodipine/indapamide) and thyroid carcinoma (thyroidectomy/131I therapy) were required to provide complete management of acromegaly and its comorbidities. At present, blood pressure and diabetes remain well controlled and the patient has not had recurrence of thyroid carcinoma.

Conclusions

If managed appropriately, most patients with acromegaly should be able to achieve disease control without excess morbidity or mortality, although success may be limited by the modes of treatment and specific drugs available to the treating physicians [3]. The main criteria for “disease control” (rather than the more impracticable concept of “cure”) involve achievement of pre-defined targets for GH and IGF-1. These are based on the levels of GH and IGF-1 that have been shown to be associated with improved symptoms and reduced frequency and severity of comorbid conditions, as well as mortality levels approaching those of the general population [3, 6]. However, beyond these biochemical targets, other factors are also important goals in the management of patients with acromegaly, such as reduction in tumor size (which can be achieved in the majority of patients receiving long-acting SSAs and, to a lesser extent, with dopamine agonists), and more targeted control of comorbid conditions [3, 6]. While some comorbid conditions may be improved to a limited degree with acromegaly-specific therapies alone, they often require other more specific therapies for comorbidities, including the use of antihypertensive, antihyperglycemic and lipid-modifying drugs to control diabetes and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease. Thus, optimal management of acromegaly encompasses biochemical control, tumor growth control and comprehensive management of the comorbidities commonly associated with acromegaly, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension and dyslipidemia, which generally respond well to standard therapy .

References

Melmed S (2009) Acromegaly pathogenesis and treatment. J Clin Invest 119(11):3189–3202

Clemmons DR (2011) Clinical laboratory indices in the treatment of acromegaly. Clin Chim Acta 412(5–6):403–409

Giustina A, Chanson P, Bronstein MD, Klibanski A, Lamberts S, Casanueva FF, Trainer P, Ghigo E, Ho K, Melmed S, Acromegaly Consensus Group (2010) A consensus on criteria for cure of acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95(7):3141–3148

Turner HE, Wass JA (2000) Modern approaches to treating acromegaly. QJM 93(1):1–6

Melmed S, Colao A, Barkan A, Molitch M, Grossman AB, Kleinberg D, Clemmons D, Chanson P, Laws E, Schlechte J, Vance ML, Ho K, Giustina A, Acromegaly Consensus Group (2009) Guidelines for acromegaly management: an update. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94(5):1509–1517

Katznelson L, Atkinson JL, Cook DM, Ezzat SZ, Hamrahian AH, Miller KK, AACE Acromegaly Task Force (2011) American association of clinical endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and treatment of acromegaly–2011 update: executive summary. Endocr Pract 17(4):636–646

Trainer PJ, Barth J, Sturgeon C, Wieringaon G (2006) Consensus statement on the standardisation of GH assays. Eur J Endocrinol 155(1):1–2

Pokrajac A, Wark G, Ellis AR, Wear J, Wieringa GE, Trainer PJ (2007) Variation in GH and IGF-I assays limits the applicability of international consensus criteria to local practice. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 67(1):65–70

Clemmons DR (2007) IGF-I assays: current assay methodologies and their limitations. Pituitary 10(2):121–128

WHO international biological reference preparations—endocrinological substances. 25 May 2011. Available at: http://www.who.int/bloodproducts/catalogue/EndoMay2011.pdf. Accessed 23 Dec 2012

Massart C, Poirier JY (2006) Serum insulin-like growth factor-I measurement in the follow-up of treated acromegaly: comparison of four immunoassays. Clin Chim Acta 373(1–2):176–179

Holdaway IM, Bolland MJ, Gamble GD (2008) A meta-analysis of the effect of lowering serum levels of GH and IGF-I on mortality in acromegaly. Eur J Endocrinol 159(2):89–95

Chanson P, Maison P (2009) Does attainment of target levels of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor I improve acromegaly prognosis? Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 5(2):70–71

Freda PU (2009) Monitoring of acromegaly: what should be performed when GH and IGF-1 levels are discrepant? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 71(2):166–170

Puder JJ, Nilavar S, Post KD, Freda PU (2005) Relationship between disease-related morbidity and biochemical markers of activity in patients with acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90(4):1972–1978

Biermasz N (2010) Pituitary gland: new consensus in acromegaly: criteria for cure and control. Nat Rev Endocrinol 6(9):480–481

Carmichael JD, Bonert VS, Mirocha JM, Melmed S (2009) The utility of oral glucose tolerance testing for diagnosis and assessment of treatment outcomes in 166 patients with acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94(2):523–527

Sherlock M, Aragon Alonso A, Reulen RC, Ayuk J, Clayton RN, Holder G, Sheppard MC, Bates A, Stewart PM (2009) Monitoring disease activity using GH and IGF-I in the follow-up of 501 patients with acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 71(1):74–81

Ribeiro-Oliveira A Jr, Faje AT, Barkan AL (2011) Limited utility of oral glucose tolerance test in biochemically active acromegaly. Eur J Endocrinol 64(1):17–22

Ribeiro-Oliveira A Jr, Faje A, Barkan A (2011) Postglucose growth hormone nadir and insulin-like growth factor-1 in naïve-active acromegalic patients: do these parameters always correlate? Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol 55(7):494–497

Grottoli S, Gasco V, Ragazzoni F, Ghigo E (2003) Hormonal diagnosis of GH hypersecretory states. J Endocrinol Invest 26(10 Suppl):27–35

Casarini AP, Pinto EM, Jallad RS, Giorgi RR, Giannella-Neto D, Bronstein MD (2006) Dissociation between tumor shrinkage and hormonal response during somatostatin analog treatment in an acromegalic patient: preferential expression of somatostatin receptor subtype 3. J Endocrinol Invest 29(9):826–830

Resmini E, Dadati P, Ravetti JL, Zona G, Spaziante R, Saveanu A, Jaquet P, Culler MD, Bianchi F, Rebora A, Minuto F, Ferone D (2007) Rapid pituitary tumour shrinkage with dissociation between antiproliferative and antisecretory effects of a long-acting octreotide in an acromegalic patient. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92(5):1592–1599

Giustina A, Mazziotti G, Torri V, Spinello M, Floriani I, Melmed S (2012) Meta-analysis on the effects of octreotide on tumour mass in acromegaly. PLoS ONE 7(5):e36411

Melmed S, Sternberg R, Cook D, Klibanski A, Chanson P, Bonert V, Vance ML, Rhew D, Kleinberg D, Barkan A (2005) A critical analysis of pituitary tumour shrinkage during primary medical therapy in acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90(7):4405–4410

Amato G, Mazziotti G, Rotondi M, Iorio S, Doga M, Sorvillo F, Manganella G, Di Salle F, Giustina A, Carella C (2002) Long-term effects of lanreotide SR and octreotide LAR on tumour shrinkage and GH hypersecretion in patients with previously untreated acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 56(1):65–71

Bevan JS (2005) Clinical review: the antitumoral effects of somatostatin analog therapy in acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90(3):1856–1863

Sandret L, Maison P, Chanson P (2011) Place of cabergoline in acromegaly: a meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96(5):1327–1335

Mazziotti G, Giustina A (2010) Effects of lanreotide SR and Autogel on tumour mass in patients with acromegaly: a systematic review. Pituitary 13(1):60–67

Annamalai AK, Webb A, Kandasamy N, Elkhawad M, Moir S, Khan F, Maki-Petaja K, Gayton EL, Strey CH, O’Toole S, Ariyaratnam S, Halsall DJ, Chaudhry AN, Berman L, Scoffings DJ, Antoun NM, Dutka DP, Wilkinson IB, Shneerson JM, Pickard JD, Simpson HL, Gurnell M (2013) A comprehensive study of clinical, biochemical, radiological, vascular, cardiac, and sleep parameters in an unselected cohort of patients with acromegaly undergoing presurgical somatostatin receptor ligand therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98(3):1040–1050

Moore DJ, Adi Y, Connock MJ, Bayliss S (2009) Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of pegvisomant for the treatment of acromegaly: a systematic review and economic evaluation. BMC Endocr Disord 9:20

van der Lely AJ, Biller BM, Brue T, Buchfelder M, Ghigo E, Gomez R, Hey-Hadavi J, Lundgren F, Rajicic N, Strasburger CJ, Webb SM, Koltowska-Häggström M (2012) Long-term safety of pegvisomant in patients with acromegaly: comprehensive review of 1288 subjects in ACROSTUDY. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97(5):1589–1597

Colao A, Ferone D, Marzullo P, Lombardi G (2004) Systemic complications of acromegaly: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and management. Endocr Rev 25(1):102–152

Lombardi G, Galdiero M, Auriemma RS, Pivonello R, Colao A (2006) Acromegaly and the cardiovascular system. Neuroendocrinology 83(3–4):211–217

Colao A, Pivonello R, Grasso LF, Auriemma RS, Galdiero M, Savastano S, Lombardi G (2011) Determinants of cardiac disease in newly diagnosed patients with acromegaly: results of a 10 year survey study. Eur J Endocrinol 165(5):713–721

Lombardi G, Di Somma C, Grasso LF, Savanelli MC, Colao A, Pivonello R (2012) The cardiovascular system in GH excess and GH deficiency. J Endocrinol Invest 35(11):1021–1029

Tita P, Ambrosio MR, Scollo C, Carta A, Gangemi P, Bondanelli M, Vigneri R, degli Uberti EC, Pezzino V (2005) High prevalence of differentiated thyroid carcinoma in acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 63(2):161–167

Jenkins PJ (2006) Cancers associated with acromegaly. Neuroendocrinology 83(3–4):218–223

Gullu BE, Celik O, Gazioglu N, Kadioglu P (2010) Thyroid cancer is the most common cancer associated with acromegaly. Pituitary 13(3):242–248

dos Santos MC, Nascimento GC, Nascimento AG, Carvalho VC, Lopes MH, Montenegro R, Montenegro R Jr, Vilar L, Albano MF, Alves AR, Parente CV, dos Santos Faria M (2012) Thyroid cancer in patients with acromegaly: a case-control study. Pituitary 16(1):109–114

Vilar L, Naves LA, Costa SS, Abdalla LF, Coelho CE, Casulari LA (2007) Increase of classic and nonclassic cardiovascular risk factors in patients with acromegaly. Endocr Pract 13(4):363–372

Tolis G, Angelopoulos NG, Katounda E, Rombopoulos G, Kaltzidou V, Kaltsas D, Protonotariou A, Lytras A (2006) Medical treatment of acromegaly: comorbidities and their reversibility by somatostatin analogs. Neuroendocrinology 83(3–4):249–257

Ben-Shlomo A, Sheppard MC, Stephens JM, Pulgar S, Melmed S (2011) Clinical, quality of life, and economic value of acromegaly disease control. Pituitary 14(3):284–294

Maison P, Tropeano AI, Macquin-Mavier I, Giustina A, Chanson P (2007) Impact of somatostatin analogs on the heart in acromegaly: a metaanalysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92(5):1743–1747

Biermasz NR, Pereira AM, Smit JW, Romijn JA, Roelfsema F (2005) Morbidity after long-term remission for acromegaly: persisting joint-related complaints cause reduced quality of life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90(5):2731–2739

Cambuli VM, Galdiero M, Mastinu M, Pigliaru F, Auriemma RS, Ciresi A, Pivonello R, Amato M, Giordano C, Mariotti S, Colao A, Baroni MG (2012) Glycometabolic control in acromegalic patients with diabetes: a study of the effects of different treatments for growth hormone excess and for hyperglycemia. J Endocrinol Invest 35(2):154–159

Bondanelli M, Ambrosio MR, degli Uberti EC (2001) Pathogenesis and prevalence of hypertension in acromegaly. Pituitary 4(4):239–249

Mishra M, Durrington P, Mackness M, Siddals KW, Kaushal K, Davies R, Gibson M, Ray DW (2005) The effect of atorvastatin on serum lipoproteins in acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 62(6):650–655

Jallad RS, Bronstein MD (2009) Optimizing medical therapy of acromegaly: beneficial effects of cabergoline in patients uncontrolled with long-acting release octreotide. Neuroendocrinology 90(1):82–92

Vilar L, Azevedo MF, Naves LA, Casulari LA, Albuquerque JL, Montenegro RM, Montenegro RM Jr, Figueiredo P, Nascimento GC, Faria MS (2011) Role of the addition of cabergoline to the management of acromegalic patients resistant to long-term treatment with octreotide LAR. Pituitary 14(2):148–156

Acknowledgments

The Latin American Knowledge Network Initiative, including meetings and preparation of this supplement, was organized and funded by Ipsen. Medical writing support was provided by Patrick Covernton on behalf of Arsenal-CDM Paris and funded by Ipsen. The authors were fully responsible for the concept and all content, were involved at all stages of manuscript development, and provided approval of the final version for submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Vilar, L., Valenzuela, A., Ribeiro-Oliveira, A. et al. Multiple facets in the control of acromegaly. Pituitary 17 (Suppl 1), 11–17 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-013-0536-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-013-0536-7