Abstract

In this paper, I explore a fundamental but under-appreciated distinction between two ways of understanding the desire-satisfaction theory of well-being. According to proactive desire satisfactionism, a person is benefited by the acquisition of new satisfied desires. According to reactive desire satisfactionism, a person can be benefited only by the satisfaction of their existing desires. I first offer an overview of this distinction. I then canvass several ways of developing a general formulation of desire satisfactionism that would capture the reactive view, and argue that all come with significant costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

It is attractive to think that well-being consists in desire satisfaction, or getting what one wants. But spelling out this theory, known as desire satisfactionism, presents us with a number of choices. Are the relevant desires those that one actually has, or those that one would have in some idealized situation? Should the theory count only present desires, or also past and future desires? Desires in the sense that covers whatever one would voluntarily choose to do, or only in the sense of what one is “genuinely attracted” to? In light of these and other such questions, philosophers have distinguished a number of interestingly different versions of the theory.Footnote 1

This paper focuses on another distinction between versions of desire satisfactionism, introduced by Brian Barry.Footnote 2 One way that Barry articulates this distinction is by drawing an analogy with the person-affecting view in population ethics. The slogan for the person-affecting view is: “We are in favor of making people happy, but neutral about making happy people.”Footnote 3 Similarly, Barry suggests, some desire satisfactionists might distinguish themselves by claiming: “We are in favor of making desires satisfied, but neutral about making satisfied desires.”Footnote 4

It will be useful to coin labels for the distinction that this slogan suggests. On the one hand, we can say, there are proactive desire satisfactionists: those who think that taking the proactive approach of acquiring new satisfied desires does directly benefit one. On the other hand, there are reactive desire satisfactionists: those who deny this, instead insisting that promoting someone’s well-being must take the form of satisfying the desires that they already have, in some sense.

In this paper, I first offer an overview of the proactive/reactive distinction. Since Barry’s brief paper in 1989, there has been relatively little direct discussion of this issue.Footnote 5 But I argue that the distinction constitutes a fundamental divide, and identify important high-level advantages and disadvantages of each approach.

I then argue that, despite the initial appeal of the reactive view, it is not easy to construct a general formulation of desire satisfactionism that is compatible with this view, and with the intuitions behind it, without incurring significant costs. Nor, I argue, can we hope to avoid these costs by instead simply adopting a purely practical theory in the spirit of the reactive view. I conclude by suggesting possible directions for future research.

2 The proactive/reactive distinction

2.1 A deep distinction

Barry introduced the distinction between the proactive and reactive views in response to an objection that John Rawls had leveled against versions of utilitarianism which rely on a desire-based theory of value. Rawls had charged that people who accept such a theory must be “ready to consider any new convictions and aims, and even to abandon attachments and loyalties, when doing this promises a life of greater overall satisfaction.”Footnote 6

Barry notes that Rawls’s objection assumes a particular interpretation of desire-based theories of value. Rawls is assuming that when we say that desire satisfaction is valuable, we mean that it would be valuable if someone had as many satisfied desires as possible. If that were true, Barry grants, Rawls’s charge would be correct: we would then be committed to claiming that it could be appropriate to change one’s desires when this would produce a greater level of satisfaction. But in fact, Barry claims, the idea that desire satisfaction is valuable is more plausibly understood as the idea that “it is a good thing for the wants that I actually have to be satisfied.”Footnote 7

Again, I am understanding Barry’s distinction in terms of the specific question of whether or not acquiring satisfied desires is directly beneficial. The proactive and reactive views, which take opposite stances on this question, are each claims which more complete formulations of desire satisfactionism will either accept or reject. The proactive view, for its part, is implied by one standard way of formulating desire satisfactionism, according to which one’s life goes better the more desire satisfaction it contains (and goes worse the more desire frustration it contains). For example, Chris Heathwood, the leading contemporary proponent of desire satisfactionism, formulates the view as follows: “One life is better for a subject than another iff it contains a greater balance of desire satisfaction over frustration than the other.”Footnote 8 Again, we will be considering formulations of desire satisfactionism that attempt to capture the reactive view later in the paper.

As we have seen, the distinction between the proactive and reactive views is one of a number of distinctions that theorists have drawn in the literature on desire satisfactionism. But it is worth appreciating how fundamental the proactive/reactive distinction is. In particular, the question of whether desire satisfactionism should take a proactive or reactive form bears directly on one of the basic questions in the philosophy of well-being: whether well-being is, in some important sense, objective or subjective.Footnote 9

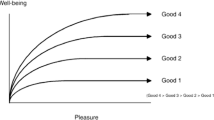

For present purposes, I will understand the view that well-being is objective as the view that well-being consists in acquiring certain objective goods and avoiding certain objective evils, where objective goods and evils are things that “are good or bad for us, whether or not we want to have the good things, or to avoid the bad things.”Footnote 10 For example, the objective list theory claims that what is good for us is to acquire the items on a particular list, such as knowledge, friendship, or achievement, while hedonism can be understood as claiming that what is good for us is to acquire one particular object, namely pleasure. And in both cases, the theories claim that well-being is a matter of acquiring such objects regardless of whether we ourselves care about them.

Proactive desire satisfactionism, I suggest, is naturally understood as taking this same basic approach. In particular, this view is naturally understood as claiming that it is good for us to acquire states of desire satisfaction, regardless of whether we have a higher-order desire for these states; this would explain why one would be made better off if one acquired more of these states by forming new satisfied desires. In contrast, proponents of the reactive view are naturally understood as denying this approach. On this view, in order for your life to go well, it is a mistake to think that there are any objective goods out there that you need to acquire, not even states of desire satisfaction. Rather, you should just try to get whatever it is that you already want.

2.2 Considerations supporting the proactive view

As I see it, the proactive view has three main high-level attractions. First, as we’ve seen, the proactive view takes the state of desire satisfaction to itself be desirable, like other putative welfare goods such as pleasure or achievement. This claim is plausible. As Heathwood points out, it is plausibly beneficial to introduce a friend to a new hobby or dish that they will come to love.Footnote 11 Similarly, there is plausibly something seriously lacking in a person’s life if they do not care about much of anything.Footnote 12

Second, reactive desire satisfactionists will need to take a position on whether it is harmful to make someone acquire a new frustrated desire. It is plausible that this would indeed be harmful. But if this is right, then there is some pressure to treat the case of making satisfied desires symmetrically.Footnote 13

Third, the proactive view is able to provide a more robust explanation of the value of life: that is, of why death would be bad for someone who would otherwise have continued living a conventionally good life.Footnote 14 On standard accounts, death is bad for one in these circumstances because it deprives one of the goods that one would have enjoyed otherwise. Other theories of well-being would say that the person would be missing out on pleasure, achievement, etc.; likewise, the proactive view could say that the person would be missing out on desire satisfaction. But on the reactive view, the person would be missing out only if the continued conventionally good life would satisfy their existing desires; they would not be benefited by the new satisfied desires that the continued life would create. But it is plausible that such a life would be a significant benefit even when it would not satisfy pre-existing desires—e.g. someone who simply does not have significant desires about their long-term future, such as a newborn infant, a carefree teenager, or a heartbroken lover.

2.3 Considerations supporting the reactive view

The reactive view, in turn, has five main high-level attractions. First, there are some cases where it is intuitive that creating new desires, and then satisfying them, does not benefit someone. The main example of this in the literature is Derek Parfit’s example of injecting someone with a drug whose only effect will be to make her wake up each morning with a strong desire to have more of the drug, which she will be able to satisfy immediately.Footnote 15 It is not plausible, Parfit claims, that this would benefit her. The proactive view implies that the injection does make the subject better off, since it would create many satisfied desires. By contrast, the reactive view is able to claim that the injection would not benefit her. There are also other examples in the literature designed to elicit the intuition that creating satisfied desires is not beneficial. For example, Christoph Fehige asks: “suppose we paint the tree nearest to Sydney Opera House red and give Kate a pill that makes her wish that the tree nearest to Sydney Opera House were red—have we really done her a favour?”Footnote 16 Again, the reactive view is able to give us the intuitive result that this course of action is not beneficial. Of course, the force of these examples is open to dispute.Footnote 17

Second, abstracting away from these specific cases, it is intuitive that the correct account of the value of desire satisfaction comes with an appropriate direction of fit. As is commonly said, desires are states which the world must fit, as opposed to beliefs, which are states which must fit the world. So one might think that something has gone wrong if we tried to achieve desire satisfaction by changing our desires to fit the world: the same thing that would be going wrong if we tried to achieve true beliefs by changing the world to fit what we already believed. Achieving desire satisfaction not by figuring out how to get the things we already want, but rather by causing ourselves to desire things we know we will be able to get, might strike us as a kind of cheating.

Third, the reactive view is supported by Connie Rosati’s idea that what is good for someone must be “made for” or “suited to” her.Footnote 18 Rosati uses these metaphors to support the internalist view that what is good for someone is constrained by facts about what that person would herself care about under appropriate conditions. More broadly, however, Rosati’s metaphors suggest that determining what is good for someone is a matter of responding to the person’s existing characteristics. It is worth noting that this intuition is independent of the idea that what is good for someone must be determined by that person’s desires or similar pro-attitudes. For example, as Sobel points out, perfectionists can argue that they respect this intuition, since they claim that what is good for someone is determined by what would fulfill that person’s existing nature.Footnote 19

Now, defenders of the proactive view could insist that they too can accommodate the idea that there must be a kind of “fit” between what is good for someone and what that person would care about. After all, once someone is made to form new satisfied desires, they will be getting what they then care about. But Rosati argues that this would not be the right kind of “fit”:

If A is subjected to hypnosis, or brain surgery at the hands of a mad neurosurgeon, or religious indoctrination, she may come to care about all sorts of things that she would not have cared about otherwise. Yet what she would care about under conditions like these may be just as alien to her as those things that she cannot care about at all. They lie within her motivational capacities but do not suit or fit her. Rather, we would generally say, she has been made to fit them.Footnote 20

As Rosati notes, the idea that well-being should be made to “fit” the subject’s existing attitudes is also related to two other commonly cited motivations for internalism. First, there is Peter Railton’s commonly cited idea (alluded to in Rosati’s passage) that what is good for someone cannot be something “alien” to that person.Footnote 21 And second, more positively, there is the idea that what is good for someone must reflect her autonomous nature.Footnote 22 These anti-alienation and pro-autonomy intuitions, which are also commonly cited as motivations for desire satisfactionism, also support a reactive approach. After all, from your current perspective, the prospect of being subjected to hypnosis, brain surgery, or religious indoctrination might well strike you as alienating, and not what you would choose for yourself, even if it would produce additional desire satisfaction.

Fourth, we have already seen that the reactive view seems to take an importantly subjective approach to welfare. That is, we have seen that whereas the proactive view claims that welfare is a matter of attaining certain goods regardless of whether the subject herself wants them, the reactive view denies this claim. This constitutes another attraction of the reactive view, because many find it attractive to think that the correct theory of welfare should in some sense be subjective, and desire satisfactionism in particular is commonly treated as the leading example of such a theory.Footnote 23

Finally, the reactive view fits well with the Humean idea that reason is the slave of the passions. Broadly speaking, the Humean perspective takes as its starting point the idea that human beings just happen to find themselves with certain intrinsic desires, and it denies that reasoning can change our intrinsic desires. As a result, the proper role of reasoning in the ethical domain is not to identify which objects are truly worth desiring—whether pleasure, knowledge, or even desire satisfaction itself—but rather simply to help us see what would satisfy our existing desires. Moreover, this Humean perspective is arguably a chief inspiration of subjective approaches to welfare. For example, David Sobel is a defender of subjectivism both about welfare and about normative reasons.Footnote 24 And when he offers his characterization of the basic dispute between subjectivists and objectivists about reasons, Sobel articulates the Humean perspective: this dispute, he writes, is over whether the ultimate source of our reasons is “merely that we happen to favor certain options and disfavor others” or is rather a result of independent standards.Footnote 25

3 How can we capture the reactive view?

3.1 Preliminaries

We have seen that there are two attractive but fundamentally opposed versions of desire satisfactionism: the proactive view and the reactive view. I will now consider how we might construct a general formulation of desire satisfactionism that captures the reactive view. Again, I argue that it is not easy to do this without incurring significant costs.

To set the stage, I will make a few schematic assumptions. I take it that most desire satisfactionists would find these assumptions uncontroversial. Now, it could turn out that the best way to capture the reactive view involves rejecting one or more of these assumptions; that itself would be an interesting result. In any event, my first assumption is as follows:

Some state of affairs p is non-derivatively good for S iff S has a relevant desire for p and p is the case. Some state of affairs q is non-derivatively bad for S iff S has a relevant desire for q and q is not the case.

Different versions of desire satisfactionism will specify which desires are “relevant” in different ways, depending, for example, on whether the desire is instrumental or non-instrumental, is properly informed, is about the subject’s own life, counts as a “genuine attraction,” and so on. For the sake of simplicity, I will ignore the strength of desires. I will also assume

S’s lifetime well-being is determined by the balance of S’s non-derivative goods over S’s non-derivative bads. The greater this balance, the higher S’s well-being.

Thus, on this model,

S’s lifetime well-being is determined by the balance of S’s relevant desire satisfactions, minus relevant desire frustrations.

Finally, I will assume the following account of benefits and harms:

An action φ benefits S iff φ increases S’s lifetime well-being. An action φ harms S iff φ decreases S’s lifetime well-being.

Timing and Bystanders

We will soon consider various specific ways that one might try to formulate the reactive view. Before we do so, however, I will now present two challenges that will complicate any such attempt.

First, while the proactive and reactive views disagree about whether it is beneficial to create desires that will be satisfied, I find it hard to deny that once someone already has a new desire, the satisfaction of that desire will make them better off.Footnote 26 In other words, it seems hard to deny the following principle:

Post-Acquisition Benefit

If S has already acquired a desire that p, then p benefits S.

For example, suppose that someone is hypnotized into wanting to own a copy of The Song of Roland. Even if we think that the hypnosis itself does not benefit her, I want to say that now that the damage is done, owning the book will indeed benefit her. The subject herself therefore now has a self-interested reason to buy the book, and others have an altruistic reason to buy it for her.

Second, let’s return to the situation before the subject has acquired the new desire. And let’s now consider the perspective of a bystander who has no control over whether the subject acquires the new desire, but who knows that the subject will in fact acquire this desire. And suppose that the bystander does have the power to ensure that the desire will be satisfied rather than frustrated. In that case, I find it hard to deny that this would benefit the subject. In other words, it seems hard to deny the following principle:

Bystander Benefit

Suppose that a bystander now knows that S will acquire a desire that p. Then if the bystander now makes it the case that p, this benefits S.

For example, suppose that a bystander has to decide now whether to order a copy of The Song of Roland for the subject, knowing that some agent is going to hypnotize the subject into wanting the book, and so that, while she doesn’t yet have any desire for the book, she will want it by the time she receives it. In this case, it seems hard to deny that the bystander does benefit the subject (i.e. increases the subject’s lifetime well-being) by ordering her the book, and the bystander therefore has an altruistic reason to do so.

Crucially, it seems to me that Post-Acquisition Benefit and Bystander Benefit are not only highly plausible in themselves, but that they should be plausible even to someone attracted to the reactive view. The reactive view says that benefitting someone is a matter of getting them what they already want, in some sense, rather than making them want things that they will be able to get. But once the subject has already been hypnotized, owning the book is, for better or worse, what she wants. Likewise, even before the hypnosis, it is already fixed, from the bystander’s perspective, that this is what the subject will want. The mere fact that the bystander has to act before the subject actually acquires the desire seems irrelevant.

The problem is that Post-Acquisition Benefit and Bystander Benefit seem, at first glance, to be incompatible with the reactive view. The reactive view denies that making satisfied desires is beneficial. But these principles both suggest that subjects can in fact benefit from the satisfaction of newly created desires. In the terminology introduced in the previous section, these principles suggest that we must therefore count these desires as “relevant,” and that seems to force us to the conclusion that making satisfied desires is in fact beneficial.

As it turns out, things are more complicated. There are in fact strategies that we might use to try to capture the reactive view while also accommodating these principles. But as we will see, each of these strategies ultimately either fails to do so, fails to respect some of the core motivations of the reactive view, or suffers other significant costs. Let’s turn to these strategies now.

4 Options

4.1 Antifrustrationism

First, we might adopt Fehige’s view that while the frustration of a desire is non-derivatively bad for the subject, the satisfaction of a desire is in fact never non-derivatively good for the subject.Footnote 27 Fehige calls this view antifrustrationism. As Peter Singer suggests, we might think of this approach as reflecting a “debit” model of the value of desires, on which we “think of the creation of an unsatisfied preference as putting a debit in a kind of moral ledger of debits and credits,” where satisfying the preference “merely cancels out the debit.”Footnote 28

Antifrustrationism would make sense of how it could be true both that the creation of a desire that will be satisfied is not beneficial (since it would just create a debit that will then be cancelled), and that once a person has the desire, its satisfaction does make them better off (since this is what cancels the debit).

Antifrustrationism has two major problems. First, as Fehige acknowledges, this view is radically pessimistic.Footnote 29 This view implies that even living a perfectly satisfied life would be no better for one than never having been born at all, and that having any unsatisfied desires makes one’s life worse than never having been born. While Fehige is willing to accept these implications, I expect that many would be hesitant to follow him.Footnote 30 In addition, it is worth noting that the motivations for the reactive view that we canvassed earlier—such as the pro-autonomy and anti-alienation intuitions, or the idea that there is something backwards about making one’s desires fit the world rather than making the world fit one’s desires—did not seem to reflect a particularly pessimistic outlook toward life. So if signing onto the reactive view does require us to accept such an outlook, then the appeal of the view might be considerably weaker than it first appeared.

Second, regardless of how plausible antifrustrationism is in itself, the view does not actually seem to capture the spirit of the reactive view, as I articulated it above. I have suggested that the proactive view shares the same objectivist approach to well-being as theories like hedonism and the objective list theory: it is naturally understood as claiming that our well-being consists in acquiring the state of desire satisfaction, just as hedonists, for example, claim that our well-being consists in acquiring the state of pleasure. In contrast, I have suggested, the reactive view can be understood as rejecting this approach: well-being isn’t a matter of acquiring states of desire satisfaction, but rather simply of satisfying whatever desires we already have.

But antifrustrationism, I claim, in fact shares this same approach. Antifrustrationism does not claim that well-being is essentially a matter of responding to the particular desires that we actually have. The theory agrees with the basic objectivist picture that well-being is to be understood in terms of the degree to which we realize certain particular states of affairs, whether or not we ourselves care about these states. It does deny that there are any objective goods, but it claims instead that well-being is a matter of avoiding an objective evil: the state of desire frustration. So just as proactive desire satisfactionism is analogous to classical hedonism, antifrustrationism is analogous to a negative version of hedonism which claims that pain is intrinsically bad but denies that pleasure is intrinsically good, or, say, to a negative objective list theory which claims that delusion is intrinsically bad but denies that knowledge is intrinsically good.

4.2 Excluding desires that have been caused in the wrong way

The remaining proposals all grant that the satisfaction of certain desires can be basically good for us, but instead attempt to capture the reactive view by pursuing a traditional desire satisfactionist strategy: imposing restrictions on which types of desires are to count as the relevant ones.

The first restriction is to exclude desires that have been caused in the wrong way. For example, Heathwood suggests that a general class of problem cases for desire satisfactionism is that of artificially aroused desires, such as an infomercial-induced desire for a Flowbee Vacuum Haircut System.Footnote 31 Now, Heathwood himself thinks that we should not find these cases troubling on reflection.Footnote 32 Still, we might be tempted to simply claim that artificially aroused desires are not relevant to well-being. Another example of this strategy comes from considering cases of adaptive preferences, or preferences formed in response to constraints on the options that are available to you.Footnote 33 We might think that preferences caused in this way should likewise not be counted as relevant to well-being.Footnote 34

But there are two problems with this strategy. First, even in clear cases of desires caused in the “wrong” way, e.g. desires implanted through hypnosis, it is still plausible that once I have the desire, satisfying it does make me better off. But this view implies that, if a desire has the wrong kind of cause, then its satisfaction can never count towards one’s well-being.

Second, this strategy still implies that a person would be better off forming more desires that would go on to be satisfied, so long as these desires would have the right kind of cause. In other words, this strategy implies that there is an objective good, the satisfaction of appropriately caused desires, and that well-being is a matter of getting as much of this good as possible. This fails to capture the spirit of the reactive view, which, as we have been characterizing it, denies that desire satisfaction of any sort is an objective good.

4.3 Excluding merely possible desires

The next restriction is to exclude merely possible desires. In other words, we could say someone’s welfare in any possible world is determined only by how well their actual desires are satisfied in that world. (Recall that in Barry’s original discussion of the proactive/reactive distinction, he endorses the idea that “it is a good thing for the wants that I actually have to be satisfied.”) This view is known as actualism.Footnote 35 Actualism would explain why, if you do not actually cause someone to have new satisfied desires, doing so would not have made them better off. This is because, in this other possible world, the desires that the person has in the actual world are not any better satisfied.

What if you do actually cause someone to have a new satisfied desire? In this case, the desire will count as relevant, so the subject will count as receiving a benefit. This might seem like a straightforward failure to respect the reactive view, but things are actually more tricky.Footnote 36

For example, suppose that an agent hypnotizes a subject into desiring to own a copy of The Song of Roland, and that the agent then buys her a copy. In this case, actualism implies that the subject receives a benefit: her actual desire to own a copy of The Song of Roland is satisfied. And it implies that the agent benefits the subject by buying her a copy of the book. But it does not imply that the agent benefits the subject, even indirectly, by giving her the desire. After all, suppose that the agent had not given the subject the desire to own the book, but had bought her one anyway. Actualism evaluates the subject’s welfare at this possible world not by reference to her desires at that world, but by reference to her desires at the actual world. And if the agent had bought her the book without giving her the desire to own it, he would still have counted as satisfying her actual desire to own the book, so actualism implies that he would have given her the same benefit. So actualism implies that giving the subject the desire does not make her better off than she would have been without the desire.

Nevertheless, actualism suffers from two serious problems. First, despite actualism’s tricks, its application to cases where agents do actually create new satisfied desires still seems to run contrary to the spirit of the reactive view. And there are several things we can say to articulate the problem. For one thing, on this view, there is still a sense in which the subject is benefited because the agent created the desire. After all, the subject’s actual desires are what they are only because of the agent’s intervention. For another thing, the view still implies that from the agent’s ex ante perspective, it is true that if he creates the desire, the subject will receive a benefit, and that if he does not create the desire, the subject will not receive a benefit. Finally, we can point out that actualism implies that subjects who are given new satisfied desires receive benefits that other subjects do not.

Second, the view’s implications about counterfactual scenarios are just implausible. It is not plausible that the agent would have benefited the subject by buying her a book that she did not want (and, we can suppose, would not have helped to satisfy any of her other desires). More dramatically, as Eden Lin points out, actualism can imply that someone would have been well off even in a world where all of their desires in that world had been frustrated, since their actual desires might still be satisfied.Footnote 37

4.4 Excluding future desires

Next, we could exclude future desires. After all, I earlier glossed the reactive view as saying that promoting well-being is a matter of satisfying the desires that someone already has. Moreover, there is in fact a tradition of formulating desire satisfactionism in such a way. More specifically, there is a tradition of formulating desire satisfactionism in a way that focuses on the subject’s present desires. As Heathwood notes, the theory has often been formulated roughly along the lines of what he calls Life Preferentism: the view that one life is better for someone than another just in case the person does, or would in some idealized situation, presently desire it more than the other.Footnote 38

As with actualism, this view is tricky. It makes the truth value of welfare judgments depend on the time at which the judgment is made. For example, on this view, before the subject forms the desire to own a copy of The Song of Roland, it is not true that the satisfaction of the desire will increase her (lifetime) well-being. But this becomes true once she forms the desire, since the desire is then no longer in the future. As a result, this view implies that, at the time of action, it is true that causing someone to develop new desires will not benefit them. But it also allows us to say that once someone has the desire, its satisfaction does benefit them.

This view faces a number of problems. First, it has trouble accounting for obvious judgments about prudence. For example, we want to say that it is beneficial to save money now if you know you will want it more in the future, even if right now you don’t care about that. Second, it has trouble accounting for the possibility of self-sacrifice.Footnote 39 Third, the time-relativity of the theory is implausible. That is, it is implausible that, even when we hold fixed all the facts about what happens in a person’s life, the truth-value of welfare judgments can depend on the time at which we are making them. Finally, the view fails to accommodate Bystander Benefit. Again, we want to say that a bystander can increase your lifetime well-being by ensuring the satisfaction of a desire that the bystander knows some other agent will create, even if the agent has not yet done so.

4.5 Idealizing

Another strategy often used in the literature to rule out problematic desires is to idealize. In particular, we might think that the desires relevant to someone’s well-being are not their actual desires, but rather those desires that they would want themselves to have upon informed and careful reflection. So it is natural to wonder whether this strategy might be helpful in the present context. Perhaps idealized subjects would not endorse potential new desires, and so perhaps idealizing versions of desire satisfactionism could capture the intuitions behind the reactive view.

But this strategy will not, in fact, help us to capture the reactive view. Idealizing versions of desire satisfactionism might take one of two forms. First, they might focus on what desires would be endorsed by an idealized version of one’s present self. Second, they might be temporally neutral, and also count what desires would be endorsed by idealized versions of one’s future self in different possible scenarios.

Suppose that someone has not yet formed new desires that would go on to be satisfied. In that case, it is easy to imagine that the idealized version of the person’s present self would not endorse the new desires. After all, by hypothesis, the person does not yet have the desires in question, so there is no reason to suppose that an idealized version of herself would have these desires. Nor is there any reason to suppose that acquiring the new desires would on balance help to satisfy the person’s existing desires. But what is doing the work here is just the fact that the theory is focusing on the person’s present self; this theory is really just one way of pursuing the strategy of excluding future desires, and so we can expect it to run into the same problems.

What about the temporally neutral version of the theory? This theory would allow that the potential new desires could be relevant if they would be endorsed by an idealized version of the person’s future self. But if the person does in fact form the new desires, then their future self will have these desires. And there is no reason to suppose that the new desires would not survive fully informed reflection, and so would be shared by the idealized version of the person’s future self. As a result, there is no reason to suppose that this idealized person would reject these desires.

4.6 Excluding choice-dependent desires

I will now argue that if we want to capture the core idea of the reactive view in our theory of well-being while accommodating Post-Acquisition Benefit and Bystander Benefit, but without accepting antifrustrationism, we will need to adopt an alternative strategy. However, we will see that even this option fails to fully respect the intuitions that motivate the reactive view.

As we’ve seen, Post-Acquisition Benefit and Bystander Benefit are in tension with the core idea of the reactive view. Post-Acquisition Benefit and Bystander Benefit imply that the satisfaction of a created desire is in fact beneficial. But the core idea of the reactive view is that creating new satisfied desires is not beneficial. We have seen that antifrustrationism can resolve this tension, but only by abandoning the subjectivism at the heart of the reactive view. So let’s suppose that, contrary to antifrustrationism, we want to say that desire satisfactions can be basically good for subjects as long as the “relevant” desires are at issue. In that case, we seem to be committed to saying both that created desires are relevant (because of Post-Acquisition Benefit and Bystander Benefit) and that they are not relevant (because of the core idea of the reactive view). But how could this be? How could the satisfaction of a given desire both be beneficial and not beneficial?

The idea of excluding future desires suggests a strategy for how it is possible to embrace both of these claims without contradiction. As we saw, this proposal makes the truth value of a welfare judgment relative to particular times: that is, it claims that the proposition that the satisfaction of a desire at a particular time is beneficial may be false at one time but true at another. This proposal illustrates a promising general strategy: rather than welfare judgments being true or false from a God’s-eye perspective, we could claim that their truth value depends on the perspective of the evaluator. This strategy could enable us to make some desires count as both relevant and not relevant: that is, we could exclude these desires from some perspectives but not from others.

What should be the dividing line between the perspectives in which created desires are to count and those in which they do not?

We want to say that, from the perspective of an agent currently in a position to create some desire, that desire should not count, but that after the desire has been created, it should count. But as we saw earlier, the mere fact that a desire is in the future relative to one’s current perspective is not an appropriate basis for excluding it.

Instead, I suggest that when an agent is in a position to create a satisfied desire, the reason why it should not count is precisely the fact that its existence depends on what the agent then does. In other words, we should exclude desires from the perspective of the agent then in a position to create them, while allowing them to remain relevant from other perspectives.

This view is supported by Bystander Benefit. We want to say that, from the perspective of an agent currently in a position to create some desire, that desire should not count, but that from the perspective of a bystander at the same time, the desire should count. But the relevant distinction between the agent and the bystander just seems to be this: one is currently in a position to determine whether the desire comes into existence, whereas the other is not. Moreover, this would also explain Post-Acquisition Benefit: after the fact, the agent is no longer in a position to determine whether the desire comes into existence, and so the desire does count as relevant from the agent’s later perspective.

Here, then, is the proposal:

Choice-relative Desire Satisfactionism (CRDS)

The satisfaction of a desire benefits S, from the perspective of an evaluator M at time t, only if the existence of this desire does not depend on what M does at t.

CRDS claims that a subject’s welfare is not a property, but a relation: a subject does not have some level of welfare simpliciter, but rather has some level of welfare relative to an evaluator at a time.

To see how CRDS works, let’s again suppose that a bystander knows that an agent will cause a subject to form a desire to own a copy of The Song of Roland. This desire will be satisfied either if the bystander now orders her a copy of the book, or if the agent later gives her a copy. (Either way, we can suppose that the subject will have formed the desire by the time she receives a copy.) If the subject’s desire is indeed satisfied—whether by the agent or by the bystander—will this benefit her? According to CRDS, the answer depends on the perspective from which we are asking the question.

From the agent’s present perspective, CRDS implies that the desire does not count as relevant, since it will be formed only if the agent now creates it. So from this perspective, the agent does not benefit the subject by giving her a new satisfied desire. Within this perspective, then, CRDS accommodates the core idea of the reactive view.

From the bystander’s present perspective, however, the subject’s desire to own the book does count as relevant, since its existence does not depend on the bystander’s present actions. So the bystander can correctly judge that he could benefit the subject by buying her the book. This illustrates how CRDS accommodates Bystander Benefit.

Similarly, if the agent does cause the subject to form a desire to own The Song of Roland then from his later perspective, the subject’s desire to own the book will be relevant, since the subject will now have formed this desire regardless of what the agent does at the later time. So once the subject has the desire to own the book, then if the agent (rather than the bystander) sends her a copy, he will count as benefiting her. This illustrates how CRDS accommodates Post-Acquisition Benefit.

CRDS, however, suffers from several serious costs. To start, it is weird to say that someone’s lifetime well-being level depends on who is evaluating it and when. Plausibly, someone’s well-being should supervene on all the facts that constitute their life, broadly construed.

This relativism is not only theoretically unappealing, but it also threatens in practice to make a mess of our welfare judgments. This is because our powers to change desires, and so the perspectives relevant to CRDS, might vary widely across people and across time. For example, you might have more power to influence the desires of your close friends and family than I do. We might often gain opportunities to change our own and others’ desires; and we might often lose them as we either take them up or leave them aside. As a result, CRDS could imply that correct welfare judgments of people’s lives will be highly variable across people and across time. Even if we take all the facts of someone’s life for granted, it might turn out that he is doing well by my lights and badly by your lights, or that he is doing well by my lights today but badly by my lights tomorrow.

Next, we have seen that CRDS accommodates the core idea of the reactive view within the perspective of an agent then in a position to determine whether to create a desire, because the desire is excluded from this perspective. However, CRDS does not exclude this desire from the perspective of a bystander or from the perspective of an agent after the desire has already been created. As a result, from either of these perspectives, the subject will count as having an additional relevant desire satisfaction if the desire is created than otherwise. So CRDS implies that, from either of these perspectives, creating the desire would in fact make the subject better off. In these respects, then, CRDS fails to accommodate the core idea of the reactive view. And a proponent of the reactive view should not be happy with this. Surely, if the reactive view is true, then a bystander should not be able to see an agent creating a satisfied desire in someone as doing something beneficial, and the agent should not be able to look back on their creation of a satisfied desire as a benefit.

In fact, things are even worse. If the subject does not have control over whether they form the desire, then CRDS will also fail to exclude the desire in question from the subject’s own perspective. This leads to two further problems. First, it means that the subject themselves should regard the creation of the satisfied desire as a benefit, even ex ante. Second, since this will not count as a benefit from the agent’s perspective, this means that what the agent should regard as a benefit can conflict with what the subject themselves correctly regards as a benefit. This is a weird kind of paternalism, and it flouts the anti-alienation and pro-autonomy intuitions that helped to motivate the reactive view in the first place.

5 Practical interpretations

I have argued that it is not easy to formulate a desire satisfactionist account of well-being that captures the reactive view without significant costs. In this section, I consider one final alternative strategy for those attracted to the reactive view: to attempt to capture the spirit of the reactive view not in our theory of well-being, but rather in terms of practical claims, claims about what we should do. I argue that this approach, too, comes with significant costs.

The basic problem is this. While the practical claim that we do not have reason to make satisfied desires is plausible in itself, we still have to answer the question: does making satisfied desires make someone better off or not? If we deny that making satisfied desires makes someone better off, then we are led back into the challenge of formulating a plausible version of desire satisfactionism that reflects this judgment. Alternatively, if we grant that making satisfied desires does make someone better off, it is hard to see why we would not have reason to do it.

Dale Dorsey has recently offered an example of this strategy.Footnote 40 Dorsey starts by distinguishing between two kinds of welfare judgments. First, there are the particular intrinsic welfare goods for any given person: those things that, were they to obtain, would directly benefit that person. Second, Dorsey notes that we also make summary judgments about how well a person is doing at a time or across times, or of what Dorsey calls a person’s welfare score.

Dorsey’s main interest, however, is not in welfare itself, but instead in our prudential reasons for action, which he characterizes as reasons specifically concerned with our own well-being. Dorsey proposes that desire satisfactionists can avoid counterintuitive implications involving the acquisition of new desires by accepting the following claims.Footnote 41 First, they should adopt a goods-based theory of prudential reasons: that is, they should claim that you have prudential reasons to perform a particular action just in case that action would promote objects that, as things stand—that is, independent of your action—constitute intrinsic welfare goods for you. Second, they should accept the object-based interpretation of desire satisfactionism: that is, they should identify our intrinsic welfare goods as the particular objects of our desires rather than as the state of desire satisfaction itself. In short, then, Dorsey claims:

You have a prudential reason to φ iff φ would promote what you desire independent of φ-ing.

Strictly speaking, Dorsey’s proposal does not count as a version of the reactive view, since I have defined this view as a claim about what benefits someone rather than as a claim about our prudential reasons. However, the claim that there is no prudential reason to make satisfied desires is surely one that those drawn to the reactive view would be eager to make. So even if the reactive view is not tenable as a theory of well-being, this proposal could at least preserve an important place for the spirit of the view. Note also that while Dorsey focuses on an agent’s prudential reasons, that is, an agent’s reasons concerned with her own well-being, his account could naturally be extended to cover our reasons for action concerned with others’ well-being.

Moreover, because Dorsey’s proposal is about prudential reasons rather than well-being itself, it is able to avoid some of the problems we encountered above. In particular, we saw that in order to accommodate what we wanted different agents to regard as beneficial, we had to relativize well-being judgments to different perspectives, which is a radical departure from how we ordinarily think about well-being. But focusing on prudential reasons avoids such problems, because reasons for action are already tied to particular actions performed by particular agents at particular times. There is nothing odd, for example, about saying both that an agent does not have reason to make someone acquire a new desire, but also that, if he does so anyway, then he will then have a reason to satisfy the desire.

Again, what is distinctive about Dorsey’s proposal is that it captures the spirit of the reactive view in a claim about prudential reasons rather than in a theory of well-being. The main problem with this proposal, as I see it, is how to explain the relationship between prudential reasons and well-being.

When it comes to determining a person’s welfare score, or overall level of well-being, Dorsey seems to assume what we have been calling the proactive view. In particular, Dorsey grants that forming new satisfied desires would make one better off. But again, Dorsey maintains that one’s prudential reasons are reasons to promote what would be intrinsically good for one independent of the action under consideration, not to do what would give one the highest welfare score. As a result, as Dorsey acknowledges, his view has the implication that one could have prudential reason to choose an action that would make one worse off than some alternative action, if the alternative action would make one better off only by changing one’s desires. And Dorsey acknowledges that this is on its face problematic. Surely, one could object, it would be absurd to claim that one could have prudential reason to do what results in a lower level of well-being.

Dorsey considers this objection by focusing on a variant of a case from Richard Arneson. In Dorsey’s version of the case, an agent could either pursue his existing dreams of Olympic-quality sports achievements, which would result in mixed success, or take a pill that would make him instead desire competence at shuffleboard, a desire which he would easily satisfy. Reflection on this case, Dorsey claims,

seems to tell in favour of refusing to grant welfare scores the power to constitute or explain prudential normativity. To my ears, it does not seem at all plausible to hold that the prudentially right action, what one owes to oneself, is to alter one’s preferences in the manner stated. It would seem a terrible tragedy for me simply to be content with minimal competence at shuffleboard … The extent to which changing my preferences is a poor ‘second-best’ does not seem to vary depending on whether taking the pill would, in fact, result in a higher welfare score.Footnote 42

However, I disagree with Dorsey’s assessment of this case. Dorsey is committed to claiming both of the following:

(1) The agent has prudential reason not to take the pill.

(2) Taking the pill would give the agent a higher welfare score: i.e., would make the agent better off.

I grant that this case does support (1). But the problem is not that Dorsey’s practical claim is counterintuitive in itself, but rather that it is in tension with his claim about what would make the agent better off. And this case does not support the claim that an agent can have prudential reason to refrain from some action even when this action would make the agent better off. To do this, we would also need to have the intuition that taking the pill would make the agent better off. But if anything, the case supports the opposite intuition. As Dorsey himself says, it would seem a “terrible tragedy” for me simply to be content with shuffleboard. And to have the intuition that taking the pill would be a “terrible tragedy” is surely to have the intuition that taking the pill would make me worse off.

Here is how I see the dialectic. Cases like Arneson’s support both the practical and the evaluative claims (i.e. the claims about well-being itself) that proponents of the reactive view would want to make. These sorts of cases are what motivated us to look for a formulation of desire satisfactionism that would capture the reactive view. But suppose that we are not willing to pay the costs that such formulations turn out to involve, and so concede that our theory of well-being has to be formulated in proactive terms. In that case, when we return to cases like Arneson’s, we will have to bite the bullet both about what would make the agent better off, and, as a result, about what the agent has prudential reason to do.

In short, Dorsey proposes a practical claim in the spirit of the reactive view, but this claim is in tension with his endorsement of a proactive approach to determining a person’s overall level of well-being, and his attempt to resolve this tension is not successful.

Dorsey could propose that we jettison talk of welfare scores—that is, of summary evaluations of agents as well or badly off—altogether, and simply focus on what we have prudential reason to do. After all, we might think, at the end of the day, isn’t what to do the important question? However, there are two problems with this. First, Dorsey’s concepts of prudential reasons and of intrinsic welfare goods are themselves defined in terms of welfare scores. Again, prudential reasons, for Dorsey, are reasons concerned with an agent’s well-being: but what is well-being if not a state of being well or badly off? And intrinsic welfare goods, for Dorsey, are those that directly benefit one. And what is it to benefit someone if not to raise their overall level of well-being? Second, and more seriously, the idea of abandoning evaluations of agents as well or badly off would just be too radical a departure from our common sense thinking.

There is one consolation for those attracted to the reactive view. Even if we do grant the proactive view about well-being, there are plausibly non-welfare-related reasons for action which can bear on cases like Arneson’s. In particular, in cases like Arneson’s, when an agent must decide between satisfying her existing desires and switching to new desires, an agent might have reasons to “be true to herself” which favor sticking to her existing desires. Likewise, when an agent must decide between satisfying someone else’s pre-existing desires and causing her to form new desires, an agent might have reasons to respect the other person’s autonomy which favor respecting the person’s existing desires. But importantly, these non-welfarist reasons will have to compete with reasons to do what will give the person the highest level of desire satisfaction and therefore of well-being. And in cases in which there is no conflict with satisfying existing desires, or where the welfare gains are great enough compared to the costs to authenticity or autonomy, we will have to concede that making satisfied desires is what one ought to do.

6 Conclusion

In this paper, I have given an overview of the distinction between the proactive and reactive forms of desire satisfactionism, and their intuitive advantages and disadvantages. And while the reactive view is initially attractive, I have argued that it is not easy to formulate desire satisfactionism in a way that captures this view without incurring significant costs.

I will conclude by suggesting three possible directions for future research. First, as we saw earlier, in introducing the proactive/reactive distinction, Brian Barry drew an analogy with the person-affecting view in population ethics, whose proponents favor “making people happy” but are neutral on “making happy people.” It would be worthwhile, then, to explore whether the best current theories in this literature, such as recent accounts of the procreation asymmetry, might provide proponents of the reactive view with models for alternative strategies that would avoid the problems I have identified here.Footnote 43

Second, while we have been focusing on an intramural debate between desire satisfactionists, we have also seen that the reactive view is arguably implicit in some of the central ideas used to support desire satisfactionism in general: in the ideas that the correct theory of welfare must be “subjective”; that it must be “made for” or “fit” the subject; and that it must respect the subject’s autonomy and avoid alienation. If the reactive view does prove to be untenable, then we should reassess whether these ideas still represent advantages for desire satisfactionism over alternative accounts of welfare.

Finally, while we have been focusing on desire satisfactionism, much of our discussion is also relevant to views according to which desire satisfaction is just one of the things that directly contributes to well-being. On these views, we would still need to say whether the desire satisfaction part of the theory should be understood in a proactive or a reactive way: that is, whether or not the acquisition of new satisfied desires would benefit the person. So it would be interesting to consider whether the debate between proactive and reactive approaches to the value of desire satisfaction would look different in this context.

Notes

Barry 1989.

Narveson 1973: 80.

Barry 1989: 281.

Barry 1989: 279.

Heathwood 2011: 25.

For an introduction to this issue, see Heathwood 2014.

I am borrowing here from Derek Parfit’s definition of the paradigmatic objectivist theory of well-being, the objective list theory (Parfit 1984: 493).

For discussion of related issues, see Tully 2017.

See Fehige 1998: 515–516.

Parfit 1984: 497.

Fehige 1998: 513–4.

For criticism of Parfit’s example, see Heathwood 2020: 103–105.

Rosati 1996: 298. Sobel 2016: 8 endorses Rosati’s intuition as a principal motivation for desire-based theories of well-being.

Sobel 2016: 8.

Rosati 1996: 302.

Railton 1986: 9.

Rosati 1996: 322.

Sobel 2016.

Sobel 2016: 287.

For defense of a similar view in cases of adaptive preferences, see Terlazzo 2017.

Fehige 1998: 518.

Singer 2011: 114.

One philosopher who is willing to follow Fehige is the famously pessimistic David Benatar; see Benatar 2006: 54–57.

Heathwood 2005: 488.

Heathwood 2005: 493–4.

For an introduction to the literature on adaptive preferences, see Terlazzo 2021.

For discussion of this approach, see Sumner 1996: 156–172.

For discussion, see Lin 2019.

Thanks to Abelard Podgorski for helping me to see the subtleties of the view.

Lin 2019: 13.

See Heathwood 2011.

Dorsey 2019.

Dorsey actually discusses this issue primarily in terms of preferences rather than desires, but the distinction does not seem important for his purposes, so for simplicity, I will stick to talking in terms of desires.

Dorsey 2019: 175 (Dorsey’s italics).

References

Bader, R. M. (2022). The asymmetry. In Ethics and existence: The legacy of Derek Parfit, 15–37. Oxford University Press.

Barry, B. (1989). Utilitarianism and preference change. Utilitas, 1(2), 278–282.

Benatar, D. (2006). Better never to have been. Oxford University Press.

Brandt, R. B. (1982). Rationality, egoism, and morality. Journal of Philosophy, 69(20), 681–697.

Bykvist, K. (2016). Preference-based views of well-being. In The Oxford Handbook of Well-Being and Public Policy, 321–346. Oxford University Press.

Cohen, D. (2020). An actualist explanation of the procreation asymmetry. Utilitas, 32(1), 70–89.

Dorsey, D. (2019). Preferences and prudential reasons. Utilitas, 31(2), 157–178.

Fehige, C. (1998). A pareto principle for possible people. In Preferences, edited by Christoph Fehige and Ulla Wessels, 509–43. De Gruyter.

Frick, J. (2020). Conditional reasons and the procreation asymmetry. Philosophical Perspectives, 34.

Handfield, T. (2011). Absent desires. Utilitas, 23(4), 402–427.

Heathwood, C. (2005). The problem of defective desires. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 83(4), 487–504.

Heathwood, C. (2011). Preferentism and self-sacrifice. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 92(1), 18–38.

Heathwood, C. (2014). Subjective theories of well-being. In The Cambridge Companion to Utilitarianism, edited by Ben Eggleston and Dale Miller, 199–219. Cambridge University Press.

Heathwood, C. (2016). Desire-fulfillment theory. In The Routledge Handbook of the Philosophy of Well-Being, edited by Guy Fletcher, 135–147.

Heathwood, C. (2019). Which desires are relevant to well-being? Noûs, 53(3), 664–688.

Heathwood, C. (2020). An opinionated guide to ‘What makes someone’s life go best.’ In Derek Parfit’s Reasons and persons: An introduction and critical inquiry, edited by A. Sauchelli, 94–113. Routledge.

Lin, E. (2019). Why subjectivists about welfare needn’t idealize. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 100(1), 2–23.

Lin, E. (2020). Future desires, the agony argument, and subjectivism about reasons. Philosophical Review, 129(1), 96–130.

Narveson, J. (1973). Moral problems of population. The Monist, 57(1), 62–86.

Overvold, M. C. (1980). Self-interest and the concept of self-sacrifice. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 10(1), 105–118.

Parfit, D. (1984). Reasons and persons. Oxford University Press.

Railton, P. (1986). Facts and values. Philosophical Topics, 14(2), 5–31.

Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of justice. Belknap.

Rawls, J. (1982). Social unity and primary goods. In Utilitarianism and Beyond, edited by Amartya Sen and Bernard Williams, 159–185. Cambridge University Press.

Sidgwick, H. (1981). The methods of ethics (7th ed.). Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett.

Singer, P. (2011). Practical ethics. Cambridge University Press.

Sobel, D. (2016). From valuing to value. Oxford University Press.

Sumner, L. W. (1996). Welfare, happiness, and ethics. Oxford University Press.

Terlazzo, R. (2017). Must adaptive preferences be prudentially bad for us? Journal of the American Philosophical Association, 3(4), 412–429.

Terlazzo, R. (2021). Adaptive preferences in political philosophy. Philosophy Compass, 17(1).

Tully, I. (2017). Depression and the problem of absent desires. Journal of Ethics and Social Philosophy, 11(2).

Weelden, J. (2019). On two interpretations of the desire-satisfaction theory of prudential value. Utilitas, 31(2), 137–156.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dietz, A. Making desires satisfied, making satisfied desires. Philos Stud 180, 979–999 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-023-01924-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-023-01924-8