Son of man,

You cannot say, or guess, for you know only

A heap of broken images, where the sun beats,

And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief

T.S Eliot, The Waste Land

Abstract

Fragmentalism was originally introduced as a new A-theory of time. It was further refined and discussed, and different developments of the original insight have been proposed. In a celebrated paper, Jonathan Simon contends that fragmentalism delivers a new realist account of the quantum state—which he calls conservative realism—according to which: (i) the quantum state is a complete description of a physical system, (ii) the quantum (superposition) state is grounded in its terms, and (iii) the superposition terms are themselves grounded in local goings-on about the system in question. We will argue that fragmentalism, at least along the lines proposed by Simon, does not offer a new, satisfactory realistic account of the quantum state. This raises the question about whether there are some other viable forms of quantum fragmentalism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Fragmentalism and its applications

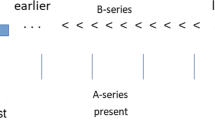

Fragmentalism was originally introduced as a new A-theory of time in Fine (2005). It has been further refined and discussed,Footnote 1 and different developments of the original insight have been proposed.Footnote 2 Recently it has been considered, and even advocated, as a possible interpretation of physical theories such as Special Relativity.Footnote 3 In a celebrated paper, Simon suggests that fragmentalism offers a new insight into Quantum Mechanics as well.Footnote 4 In particular, Simon contends that fragmentalism delivers a new realist account of the quantum state—which he calls conservative realism—according to which: (i) a quantum state provides a complete description of a given physical system, (ii) a quantum (superposition) state is groundedFootnote 5 in its terms,Footnote 6 and (iii) the superposition terms are themselves grounded in local goings-on about the components of the system in question—if the system is composed of other subsystems. Much deserves to be said about the details of Simon’s proposal. Yet, in this paper, we simply focus on his main insight about the quantum domain.Footnote 7 This key insight, we take it, is to identify different terms in a superposition state with state of affairs that belong to different Fine’s fragments. In what follows we offer an argument against this identification.

2 Fragments and superpositions

Simon (2018) takes fragmentalism to be any metaphysical view which incorporates the insight

[T]hat there is a symmetric coordination relation between facts, such that facts that are pairwise incompatible (like Hugh’s being happy and Hugh’s being sad) can both obtain provided that they are not related by this relation (Simon 2018, p. 123).

A little more precisely, a fragment is a maximal collection of states of affairsFootnote 8 that are bound together by the “symmetric coordination relation”.Footnote 9 The latter can be cashed out in different ways. Lipman (2015), whose terminology is explicitly adopted by Simon, exploits a primitive notion of co-obtainment. In his words, states of affairs that co-obtain “form a unified qualitative manifestation of the relevant objects, one single bit of world within which the things are a certain way”.Footnote 10 States of affairs that fail to co-obtain, instead, cannot be “the case together, [...] they do not make for a unified chunk of world”.Footnote 11 Two incompatible states of affairs can both obtain under the hypothesis that they do not also co-obtain. Similarly, Iaquinto (2020) resorts to the primitive notion of obtainment-within-a-fragment. When a state of affairs obtains within a given fragment, that state of affairs exists relative to that fragment. While two incompatible states of affairs can both constitute reality, they cannot obtain within the same fragment, and so they cannot exist relative to the same fragment. Yet another option is to cash out the symmetric coordination relation in terms of binary fusion, as in Loss (2017). Although two incompatible states of affairs can both constitute reality, reality cannot be constituted by their binary fusion. Regardless of their differences, what these interpretations of fragmentalism share is the idea that incompatible states of affairs that belong to different fragments cannot obtain together. In the case of tense the point is straightforward. If moments of time are conceived of as fragments, as in Fine (2005, pp. 308–310), it is clear that states of affairs belonging to two collections cannot be the case together. Socrates can be sitting at one moment and standing at another, but there is no moment at which he is both sitting and standing—that is, no fragment in which those two state of affairs obtain together.

The contention is that fragmentalism as described above offers a new realistic reading of the state of a quantum system. Simon (2018) provides a fragmentalist account of both a simple superposition state, and an entangled state. We mainly restrict our attention here to the simpler superposition case, for it is enough to underwrite our main argument.Footnote 12 Consider the superposition state Simon himself considers, namely the following state of an electron:

Quantum state \(|\psi \rangle\) is a state in which an electron is in a superposition of spin-up and spin-down along the z-axis. As we mentioned already, Simon’s contention is that we should identify the superposition terms in (1) with states of affairs that belong to different fragments.Footnote 13

This delivers the following fragmentalist understanding of quantum state (1), which we take directly from Simon:Footnote 14

[T]he fragmentalist can countenance the face value reading of (1): the state of affairs of the electron’s having up-spin along the z-axis obtains, and so does the state of affairs of that same electron’s having down-spin along the z-axis: but these two states of affairs do not co-obtain, and indeed, as they are incompatible, they cannot co-obtain (2018, pp. 139–140).

Note that this cannot be the end of the story.Footnote 15 This is because the state:

has exactly the same terms, and is a very different quantum state that leads to completely different empirical predictions. As a matter of fact, (1) is equivalent to \(|\uparrow _x\rangle\), whereas (2) is equivalent to \(|\downarrow _x\rangle\). In general, the problem is the following: every view that focuses only on superposition terms will lose phase correlations between those terms. In the particular case at hand, it seems, a natural fix suggests itself. The quantum fragmentalist should say that (1) also describes a fragment where the state of affairs of the electron having spin-up along the x-axis obtains, whereas (2) also describes a fragment where the state of affairs of the electron having spin-down along the x-axis obtains.Footnote 16 The same holds for spin-y and all other relevant quantum observables. The challenge would be to provide such a story in all possible quantum cases. And note that not any story would do. It would have to be a story that is grounded in local goings-on, if we are to vindicate full-blown conservative realism. We do not want to push this line of argument here.

But we do want to suggest that the challenge is serious. The worry here is that the easy fix we suggested might look holist, in that it enshrines quantum information about both superposition terms. But—so the worry continues—avoidance of holism was part and parcel of the new conservative realism that quantum fragmentalism was supposed to deliver. There is a fair reply here on behalf of the quantum fragmentalist. The most interesting form of holism that fragmentalism promises to avoid is holism about composite systems. To put it roughly, according to such holism, the state of a composite system does not supervene on the states of its component parts. Nothing like this is at stake here: we are only dealing with a simple physical system in a superposition. Granted. But the worry resurfaces if composite systems are taken into account. Consider the following two Bell-states:

States (3) and (4) are two-particle states—that is, states of a composite system—that have the same terms, yet they are different. How can the quantum fragmentalist distinguish them? The easy fix we suggested does look holist in the relevant sense here, for it concedes that (3) and (4) describe also states of affairs about the composite two-particle system.Footnote 17

As we said already, we will leave this as a challenge—a serious one we think, yet perhaps not insurmountable. This is partly because we believe there is a more serious objection against this particular way of constructing quantum fragmentalism. In the next section we will argue that the fragmentalist reading of the quantum state—should the previous challenge be successfully met—is at odds with some quantum phenomena, in particular with quantum interference.

3 Against quantum fragments

The main argument against the identification of superposition terms with state of affairs in different fragments we have in mind is a simple two-premise argument:

- P \(_1\).:

-

Given the basic tenets of fragmentalism, states of affairs that belong to different fragments do not—and in fact, cannot—interact.

- P \(_2\).:

-

Different terms in a superposition state can—and indeed sometimes do—interact.

- C.:

-

Superposition terms are not states of affairs that belong to different fragments.

Clearly, the burden of such simple argument lies in the defence of premises P \(_1\) and P \(_2\).

Here is an argument for P \(_1\). Although there are different ways to pin down the notion of “fragmentation”, as seen in Sect. 2, the minimal idea is that states of affairs that do not belong to the same fragment cannot obtain together. Simon himself seems to concede this in the passage we quoted above. Now consider an interaction between the states of affairs \(s_1\) and \(s_2\). It seems clear that obtaining together is a necessary condition for (the possibility of) interaction.

In effect, a few words of clarification are in order. Here and in what follows we use the term “interaction” in a specific sense. We don’t mean to give a definition of interaction. Rather we want to provide an informal gloss of the specific sense at issue here.Footnote 18 In this specific sense, we contend, x interacts with y if and only if x acts on y and y acts on x to produce effect z, or, equivalently, x acts together with y to produce effect z. This terminology is particularly useful in this context for it highlights that x and y have to obtain together, in order to produce z. Once again, we do not mean the previous bi-conditional to be read as a definition. Yet we can provide examples. There are certain dances where the dancers have to act together in order to produce certain figures. In a chemical reaction the reactants interact in this strict sense in order to produce a different substance or compound. They too, like the dancers, act together. In this specific sense, we claim, \(s_1\) and \(s_2\) interact only if they obtain together.Footnote 19

But \(s_1\) and \(s_2\) can obtain together only if they belong to the same fragment. Thus, according to fragmentalism, state of affairs that belong to different fragments cannot interact, as per premise P \(_1\).Footnote 20

We will argue for premise P \(_2\) by way of an example. That is, we will invoke interaction of different superposition terms to explain some basic quantum phenomena such as the existence of an interference pattern in the double-slit experiment.

Let us briefly review the double-slit experiment itself, in the classical formulation of Feynman (1963). A particle source, say an electron gun, emits electrons of the same wavelength, and thus of the same momentum. The gun fires a large amount of electrons, in the direction of two small slits, slit 1 and 2. Behind the two slits we put a screen that is covered with a large number of closely spaced particle detectors.

For each round of experiments we fire billions of electrons at the screen. First we close one of the slits, say slit 1, forcing the electrons to pass through slit 2 before hitting the screen. We make a histogram of the number of electrons arriving at each detector on the screen as a function of detector positions. When only one slit is open, we get exactly the pattern we expect from classical physics. Let us call it a single-slit pattern. We obtain a single-slit pattern if we open slit 1 and close slit 2.

Now, we open both the slits. What we get is famously an interference pattern which is different from the classically expected pattern that we get by simply summing over the two single-slit patterns. Here is a possible semi-classical explanation. Some electrons pass through slit 1, some electrons pass through slit 2, and then they somehow interact with each other to produce the interference pattern.

But now we let our electron gun fire just one electron at a time. No interaction with any other electron is possible, for we fire electrons only once the preceding one has been detected on the screen. The astonishing behaviour exhibited by the electrons is that they still produce the interference pattern. How can we explain such a behaviour?

Here is the classical quantum mechanical explanation. The quantum state of each electron can be taken to be, given suitable simplifications,Footnote 21 the following superposition:

where \(|1\rangle\) and \(|2\rangle\) represent the states of passing through slit 1 and slit 2 respectively. In the words of Barrett, these states represent

[T]wo wave-packets [that] spread out and interfere with each other in the region between the barrier and the screen (2001, pp. 5–6, italics added).

Now, state (5) is a simple superposition state, the same as state (1) which Simon considers. And clearly, if x interferes with y, x interacts with y, interference being a particular case of interaction. As Lewis (2016) puts it:

“[I]interference” is just a name for interaction between two wave components (Lewis 2016, p. 98).

As a matter of fact, Lewis describes the situation in terms of interaction directly:

The wavefunction for the electron splits into two packets, one passing through the left slit and the other passing through the right slit, and beyond the slits the two terms come together and interact to produce the characteristic interference wave pattern at the screen (Lewis 2016, p. 62, italics added).

The general idea is simple enough: it is exactly the interaction of the two superposition terms that produces the interference pattern we observe.Footnote 22 We can provide some simple algebraic details about such an interaction. Let \(P_1(e)\) and \(P_2(e)\) be the probability distribution associated with an electron striking the screen directly opposite slit 1 and slit 2 respectively. \(P_{12}(e)\) is the probability distribution when both slits are open. Then, we have quantum interference—a particular kind of quantum interaction—if and only if \(P_{12}(e) \ne P_1(e) + P_2(e)\).

In effect, what we observe is the following:

where \(\theta\) is the phase difference between the two wave-packets \(|1\rangle\) and \(|2 \rangle\). The last term on the right hand-side of (6) is known as the interference term. It provides, so to speak, a quantitative measure of the interaction between the two terms of the superposition state. Note that it depends on both the superposition terms, as it should, for it encodes something about their interaction. This gives us premise P \(_2\), or so we contend.Footnote 23

4 Varieties of quantum fragmentalism

The argument in Sect. 3—if correct—shows that fragmentalism, at least along the lines proposed by Simon (2018), does not offer, in general, a new satisfactory realistic account of the quantum state. This raises the question about whether there are some other viable forms of quantum fragmentalism.Footnote 24

Perhaps one can suggest that Simon’s version of quantum fragmentalism can be applied only to entangled states. The thought here is that when we deal with entangled states we should consider environmental decoherence.Footnote 25 Environmental decoherence is, extremely roughly, the suppression of quantum interference due to interaction—and successive entanglement—of a system with the environment: in the case of decoherence the superposition terms behave semi-classically in that we observe no interaction between them. The rationale behind this move is readily appreciated: we argued in Sect. 3 that the problem for quantum fragmentalism is due to the interaction of the superposition terms. If we could restrict in a principled way the application of fragmentalism to those quantum states that exhibit no such interaction, it seems that the problem would go away.

But even this is not enough: for there are cases in which entanglement with the environment and successive decoherence do not suppress the interaction completely—algebraically the interference term is close to zero but still non-zero. For such cases, the argument in Sect. 3 still applies. And even for the cases in which decoherence does suppress the interference completely, modal considerations should be brought to bear. For fragmentalism entails not only that states of affairs belonging to different fragments do not interact, but that they cannot interact. But for microscopic systems decoherence is reversible. We can undo the effects of the interaction with the environment and observe interference effects.Footnote 26

One last possibility is to consider fragmentalism as only applicable to the quantum entangled state of the entire universe. In such a case, decoherence will suppress quantum interference very effectively. As a matter of fact, as Lewis points out

[D]ecoherence for macroscopic systems is rapid, very complete and highly irreversible. This means that if the state of a macroscopic system comes to have two components, these components will not exhibit any appreciable interference effects (...) This means that for all practical purposes the two components do not interact (Lewis 2016, p. 98).

Let us spend a few words on this possibility. First, we should recognise the explicit limitations of the proposal. In general, we would have a use for quantum fragmentalism only in the case of entangled decoherent (sub)-systems. The universe might be one prominent example. But there seems to be other relavant systems that would be outside the scope of a fragmentalist account. These include systems we routinely experiment on, such as the ones involved in the double-slit experiment of Sect. 3.

Second, we should note that the challenge we raised in Sect. 2 becomes important here. Consider the universe as a case in point. Suppose the challenge in Sect. 2 is not met. That is, suppose the only way for the fragmentalist to distinguish different quantum states with the same terms is to concede that those states describe also states of affairs of the relevant composite system—the universe in the case at hand. Then quantum fragmentalism seems dangerously close to be Everettian Quantum Mechanics in disguise.Footnote 27 Finally, in this case even subtler details about modal considerations should be brought to bear. As we said, fragmentalism entails that some states of affairs belonging to different fragments cannot interact. If this is supposed to have the force of metaphysical impossibility, then decoherence theory is not likely to underwrite such a conclusion. But even if only nomological necessity is involved, it is unclear whether decoherence will be enough to support the modal conclusion that superposition terms cannot interact. Consider Lewis’s passage we just quoted. Lewis is cautious—rightfully so, we might add—in claiming that the components of the quantum state of a macroscopic system do not interact, for all practical purposes. This falls short of supporting the conclusion that there is no interaction in any metaphysically and nomologically interesting sense, let alone the possibility of such an interaction. Here is a way of looking at things. It is—at least partly—because of the possibility of interference that we use complex valued-functions to represent quantum states, rather than say, real-valued ones. For interference effects depend on amplitude and phases, and complex numbers capture this aspect explicitly, in that they are characterised by amplitudes and phases themselves.

In any event, this seems to us one of the most promising way to develop a (perhaps restricted) fragmentalist understanding of quantum mechanics: to investigate the interaction between modal considerations at work in (modal) fragmentalism and modal claims that can be supported by decoherence theory. However, in the light of the above, it seems safe to say that the overall conclusion still stands. In general, quantum terms are not states of affairs that belong to different fragments. The world is not a heap of broken quantum fragments.

But even if Quantum Mechanics were not to offer any shelter to the fragmentalist, she should not despair. She should just look at The Progress of the Soul, where it is written:

What fragmentary rubbish this world is.Footnote 28

Notes

See Simon (2018). The paper offers some insightful remarks on the bearing of fragmentalism on the metaphysics of persistence as well. We will not discuss this here.

We are not using this term in any technical sense here, so as to suggest that grounding—in the technical sense of, e.g., Fine (2012)—is the right relation to cash out the relevant claim.

We are abusing terminology here, for arguably the terms in a superposition state, and the superposition itself are mathematical objects, whereas the quantum state is supposed to be the referent of those mathematical objects. This conflation is widespread in the literature and mostly harmless. For a recent, insightful discussion see Maudlin (2019, pp. 79–93).

We leave many interesting questions aside: does fragmentalism really deliver (i)–(iii) above? What is the main difference between this understanding of the quantum state and some relative state readings, such as the one in Conroy (2012)? How is this variant of quantum fragmentalism related to the so-called primitive ontology approach—see e.g. Allori (2013)—which Simon explicitly mentions?—and so on.

Simon uses both “facts” and “states of affairs”. We will stick to the latter in what follows for Simon uses the “state of affairs” terminology in the quantum context. See e.g. the passage we quote later on in this section. Notice that, strictly speaking, fragmentalism is not necessarily committed to an ontology of facts or states of affairs. One might just resort to some kind of entities able to instantiate fundamental properties and relations. Reference to facts or states of affairs can also be avoided by resorting to a proper “in reality” sentential operator, as in Fine (2005, p. 268).

See Fine (2005, p. 281).

Lipman (2015, p. 3127).

Lipman (2015, p. 3128); italics in the original.

We will consider entanglement later on, and then again in Sect. 4.

In the limiting case in which there is only one state of affairs in a fragment one could identify superposition terms with fragments directly. In effect, this is what some passages in Simon (2018) explicitly suggest. For example this one:

In other words, fragmentalism offers a precise answer to a vexing question, one that many take to afford only imprecise answers: what is a quantum mechanical “branch”? The fragmentalist answer is that a branch is a fragment (Simon 2018, p. 140).

We just need to be reminded that “branches” correspond to superposition terms.

In what follows, the question of how to make sense of the coefficients in the quantum state is left aside. However, Simon himself suggests different interpretative possibilities. See Simon (2018, pp. 140–141).

Here we are indebted to Craig Callender.

This fragment has to be different from the ones in which the spin-z state of affairs obtains so as not to run afoul of generalised uncertainty principles.

We will come back to this in Sect.4. Thanks to an anonymous referee here.

This is because we don’t want to deny that there are other uses of the term “interaction” that do not conform to the characterisation we provide in the main text.

Perhaps a case can be made that the impossibility of interaction can be argued for in more general terms if only one recognises that, in the case at hand, we are not dealing with a temporal understanding of fragments, but rather with a broadly modal understanding. This modal nature of fragments is the one that is responsible for the impossibility of interaction between two states of affairs that belong to different fragments—so the thought goes. This is surely a fascinating suggestion—we owe it to Giuliano Torrengo. Yet, it clearly deserves a detailed account of the modal nature of the fragments in the case at hand. We are afraid this calls for independent scrutiny. We believe that the more modest remarks on the specific sense of “interaction” that is at stake here suffice to bring the point home. So we will leave it at that.

Clearly, if the states of affairs cannot interact, they do not.

Strictly speaking, the state is represented by a plane wave \(|\psi \rangle = e^{ipx/\hbar }\) which is a much more complicated superposition of position terms. This simplification is harmless in the present context. See also Barrett (2001, p. 6).

A fragmentalist could try to argue that incompatible states of affairs cannot co-obtain at the fundamental level, but that they could co-obtain at a derivative one. This would make room for arguing that, at the fundamental level, there is no interference pattern. As it were, the interference pattern only emerges at a derivative level. This was suggested to us by Roberto Loss. While we agree that this is a fascinating suggestion that is worth exploring, we think that more should be said to be able to evaluate it. First, we need to be told what counts as fundamental and derivative levels in the quantum case. Second, we need to see an argument to the point that interference between superposition terms only belongs to the derivative level. We are not aware of any such arguments in the literature. In the light of the above, we will simply claim that, absent such arguments, the burden of the proof is on the objector.

Jonathan Tallant suggested to us that the argument we put forward may be seen as a particular instance of a much more general argument. The general argument would be that fragmentalism would struggle, if not fail, to accommodate the case in which two incompatible states of affairs that belong to two different fragments are such that some of their constituents—that are not necessarily numerically distinct—are related by an external relation. We think this is a suggestion worth exploring, but it goes well beyond the scope of the paper.

Some of which are suggested by some passages by Simon himself.

For a philosophically minded introduction see Bacciagaluppi (2003).

To wit, the argument depends on the following principle governing the interaction between temporal and modal operators: If sometimes \(\phi\), then Possibly \(\phi\). This is logically equivalent to what Dorr and Goodman call Perpetuity, i.e., If Necessarily \(\phi\), then Always \(\phi\)—where Sometimes and Always are temporal operators defined in terms of the standard Priorean operators. For a defense of Perpetuity see Dorr et al. (2019).

John Donne, The Second Anniversary: Of the Progress of the Soul. In J. Donne, 2010, The Complete Poems of John Donne, Robbins, R. (ed), Second Edition, Routledge, p. 870.

References

Allori, V. (2013). Primitive ontology and the structure of physical theories. In D. Albert & A. Ney (Eds.), The wavefunction. Essays in the metaphysics of quantum mechanics (pp. 58–75). Oxford: OUP.

Bacciagaluppi, G. (2003). The role of decoherence in quantum mechanics. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/qm-decoherence/.

Barrett, J. A. (2001). The quantum mechanics of minds and worlds (2nd ed.). Oxford: OUP.

Conroy, C. (2012). The relative facts interpretation and Everett’s note added in proof. Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 43, 112–120.

Correia, F., & Rosenkranz, S. (2012). Eternal facts in an ageing universe. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 90, 307–320.

Dorr, C., & Goodman, J. (2019). Diamonds are forever. Noûs,. https://doi.org/10.1111/nous.12271.

Feynman, R. (1963). The Feynman lectures on physics. Boston: Addison and Wesley.

Fine, K. (2005). Tense and reality. In his modality and tense (pp. 261–320). Oxford: OUP.

Fine, K. (2012). A guide to ground. In F. Correia & B. Schnieder (Eds.), Metaphysical grounding: Understanding the structure of reality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hofweber, T., & Lange, M. (2017). Fine’s fragmentalist interpretation of special relativity. Noûs, 51, 871–883.

Iaquinto, S. (2019). Fragmentalist presentist perdurantism. Philosophia, 47, 693–703.

Iaquinto, S. (2020). Modal fragmentalism. The Philosophical Quarterly, 70, 570–587.

Lewis, P. (2016). Quantum ontology. A guide to the metaphysics of quantum mechanics. Oxford: OUP.

Lipman, M. (2015). On Fine’s fragmentalism. Philosophical Studies, 172, 3119–3133.

Lipman, M. (2016). Perspectival variance and worldly fragmentation. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 94, 42–57.

Lipman, M. (2018). A passage theory of time. In K. Bennett & D. Zimmerman (Eds.), Oxford studies in metaphysics, 11, 95–122.

Lipman, M. (2020). On the fragmentalist interpretation of special relativity. Philosophical Studies, 177, 21–37.

Loss, R. (2017). Fine’s McTaggart: Reloaded. Manuscrito, 40, 209–239.

Maudlin, T. (2019). Philosophy of physics. Quantum theory. Princeton: PUP.

Pooley, O. (2013). Relativity, the open future, and the passage of time. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 113(Part 3), 321–363.

Simon, J. (2018). Fragmenting the wave function. In K. Bennett & D. Zimmerman (Eds.),Oxford studies in metaphysics, 11, 123–145.

Torrengo, G., & Iaquinto, S. (2019). Flow fragmentalism. Theoria, 85, 185–201.

Torrengo, G., & Iaquinto, S. (2020). The invisible thin red line. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1111/papq.12314.

Wallace, D. (2012). The emergent multiverse: Quantum theory according to the Everett interpretation. Oxford: OUP.

Wilson, A. (2020). The nature of contingency: Quantum physics as modal realism. Oxford: OUP.

Acknowledgements

For discussions on previous drafts of this paper we would like to thank Craig Callender, Roberto Loss, Giuliano Torrengo, Jonathan Tallant, Jessica Wilson, Cristian Mariani, Alberto Corti, and audiences at Milan, Turin and, virtually, Leiden. We would also like to thank an anonymous referee for this journal for her insightful suggestions. Claudio Calosi acknowledges the generous support of Swiss National Science Foundations (SNF), project number PCEFP1\181088. Samuele Iaquinto has been funded by the PRIN Project “Logic and Cognition” (Italian Ministry of Education, University, and Research, 2019-2021).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Torino within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iaquinto, S., Calosi, C. Is the world a heap of quantum fragments?. Philos Stud 178, 2009–2019 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-020-01520-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-020-01520-0