Abstract

Moral relativists often defend their view as an inference to the best explanation of widespread and deep moral disagreement. Many philosophers have challenged this line of reasoning in recent years, arguing that moral objectivism provides us with ample resources to develop an equally or more plausible method of explanation. One of the most promising of these objectivist methods is what I call the self-interest explanation, the view that intractable moral diversity is due to the distorting effects of our interests. In this paper I examine the self-interest explanation through the lens of the famine debate, a well-known disagreement over whether we have a moral obligation to donate most of our income to the global poor. I argue that objectivists should reduce their confidence that the persistence of the famine debate is due to the distorting influence of self-interest. If my argument is on target, then objectivists may need to supply a stronger explanation of moral disagreement to defend their view against the threat of moral relativism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For discussion, see Tersman (2006: 31–33). Fraser and Hauser (2010: 551–556) also use empirical research to show that familiar objectivist methods fail to account for a real-world moral disagreement. However, while their work is a significant improvement over armchair speculation, it suffers from the same limitations that I argue plague Doris and Plakias.

I focus on expert rather than folk moral disagreement because it provides a more telling test case of objectivist methods, as objectivists themselves acknowledge (Wedgwood 2014: 26). For even granting that objectivists can account for folk disagreement, they may not be able to account for expert disagreement if moral philosophers are more likely than novices to arrive at true moral beliefs.

For a similar characterization, see Gowans (2015). We might formulate moral objectivism as a purely metaphysical thesis but most versions include an epistemological component (see for example Boyd 1995: 307; Gowans 2000: 3; Thomson 1996: 68). Presumably, the reason is that absolute moral truth without justified moral belief is, as Enoch says, “a very small comfort” (2011: 189).

See footnote 2.

While there is some disagreement about whether foreign aid helps or harms the poor, I argue in earlier work that the famine debate is not due to conflicting non-moral beliefs (Seipel 2019).

Anti-radicalism takes different forms. Some anti-radicals seem to deny that we have an obligation to give any money to foreign aid, such as Narveson (2013) and Otteson (2006). Others, like Murphy (2000) and Appiah (2006), argue that we only have to help a little. Still others think we have moderately demanding duties to provide assistance, including Cullity (2004), Lichtenberg (2014), and Miller (2010). What these commentators have in common is their rejection of the more radical claim that morality requires us to give away most of our income.

For a relativist explanation of the debate, see especially Harman (1996: 24–25).

I am indebted in this argument to proponents of intuition-based approaches in ethics, especially Hales (2006: 171–172) and Williamson (2011: 219–220), both of whom defend their view on the basis of an analogy with other fields. However, it is important to note that whether training and experience improve our ability to debias is independent of their impact on our intuitive reactions to thought experiments. For a helpful overview of the debate over philosophical expertise, see Nado (2014).

I am grateful to Nathan Ballantyne for prompting me to address this issue.

This is because, intuitively, it is hard to see we can be justified in affirming beliefs that we know to be unreliably formed. See McGrath (2007) for the suggestion that moral disagreement poses a greater threat to the possibility of moral knowledge than to the claim that there are absolute moral truths.

If objectivists deny this point, then we may wonder whether objectivism supplies us with the best explanation for the gradual emergence of consensus on at least some moral matters (such as slavery). For, plausibly, instead of appealing to absolute moral truths to account for this convergence, we might instead explain it in terms of irrational influences (Tersman 2006: 52–53). But then objectivists would lose perhaps the best evidence for their view (Gowans 2000: 17; Nagel 1986: 145–149).

Objectivists may appeal to some factor other than self-interest to show that the famine debate is unlike the debate over slavery. But then of course we are no longer within the realm of the self-interest explanation. I return to the worry that anti-radical intuitions are biased below.

Why was the rationalization not identified during the peer review process? One reason may be that the studies were published in a scientific journal with an industry representative on its editorial board (Tong and Glantz 2007: 1846). For evidence that Ballantyne would agree with my proposal, see his remarks on climate change and the problem of conflicting expert testimony (2019: 220–221, 232).

Less cynically, Unger might be motivated by a desire to increase donations to foreign aid. Significantly, he not only instructs us on where to mail our checks but also includes toll-free phone numbers for those who would rather donate by credit card (1996: 3, 175). While it is true that he may only wish to increase donations because he thinks we should donate, it is also possible that he thinks we should donate because he wishes to increase donations.

For discussion of this point, see especially Berkey (2016: 3022ff).

Of course, objectivists may bite the bullet and argue that the abortion debate is due to biased intuitions. But then it is not clear that they are justified in their beliefs about abortion. On the other hand, if they deny that the abortion debate stems from biased intuitions, then the self-interest explanation seems to have rather limited application. If it cannot even account for a debate in which there appears to be a great deal at stake in terms of our interests, we should wonder whether, and to what extent, it is able to account for DMR.

References

Appiah, K. A. (2006). Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a world of strangers. New York: W. W. Norton.

Ballantyne, N. (2015). Debunking biased thinkers (including ourselves). Journal of the American Philosophical Association, 1, 141–162.

Ballantyne, N. (2019). Knowing our limits. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Berkey, B. (2016). The demandingness of morality: Toward a reflective equilibrium. Philosophical Studies, 173, 3015–3035.

Boyd, R. (1995). How to be a moral realist. In P. Moser & J. D. Trout (Eds.), Contemporary materialism. London: Routledge.

Brandt, A. (2007). The cigarette century. New York: Basic Books.

Brandt, R. (2001). Ethical relativism. In P. Moser & T. Carson (Eds.), Moral relativism: A reader. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brink, D. (2000). Moral disagreement. In C. Gowans (Ed.), Moral disagreements. London: Routledge.

Critcher, C., & Dunning, D. (2011). No good deed goes unquestioned. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 1207–1213.

Cullity, G. (2004). The moral demands of affluence. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Doris, J., & Stitch, S. (2005). As a matter of fact: Empirical perspectives on ethics. In F. Jackson & M. Smith (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of contemporary philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Doris, J. M., & Plakias, A. (2008). How to argue about disagreement: Evaluative diversity and moral realism. In W. Sinnott-Armstrong (Ed.), Moral psychology (Vol. 2). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Dunning, D. (2016). False moral superiority. In A. Miller (Ed.), The social psychology of good and evil (2nd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

Eagly, A. (2007). In defense of ourselves. In M. Hewstone, et al. (Eds.), The scope of social psychology. New York: Psychology Press.

Ehrlinger, J., Gilovich, T., & Ross, L. (2005). Peering into the bias blind spot. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 680–692.

Enoch, D. (2011). Taking morality seriously: A defense of robust realism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fetchenhauer, D., & Dunning, D. (2010). Why so cynical? Psychological Science, 21, 189–193.

Finlay, S. (2008). Too much morality? In P. Bloomfield (Ed.), Morality and self-interest. New York: Oxford University Press.

Flynn, F., & Lake, V. (2008). If you need help, just ask. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 128–143.

Fraser, B., & Hauser, M. (2010). The argument from disagreement and the role of cross-cultural empirical data. Mind and Language, 25, 541–560.

Goethals, G. (1986). Fabricating and ignoring social reality. In J. Olson, C. P. Herman, & M. Zanna (Eds.), Relative deprivation and social comparison (Vol. 4). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Gowans, C. (2000). Introduction: Debates about moral disagreements. In C. Gowans (Ed.), Moral disagreements. London: Routledge.

Gowans, C. (2004). A Priori refutations of disagreement arguments against moral objectivity: Why experience matters. Journal of Value Inquiry, 38, 141–157.

Gowans, C. (2015) (Fall 2015 Edition). Moral relativism. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. E. Zalta. Retrieved May 30, 2019 from http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/moral-relativism/.

Hales, S. (2006). Relativism and the foundations of philosophy. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Harman, G. (1996). Moral relativism and moral objectivity. Cambridge: Blackwell.

Horton, K. (2004). Aid and bias. Inquiry, 47, 545–561.

Kennedy, K., & Pronin, E. (2008). When disagreement gets ugly: Perceptions of bias and the escalation of conflict. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 833–848.

Kenyon, T. (2014). False polarization: Debiasing as applied social epistemology. Synthese, 191, 2529–2547.

Kintz, B. (1977). College student attitudes about telling lies. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 10, 490–492.

Kish-Gephart, J., Detert, J., Trevino, L., Baker, V., & Martin, S. (2014). Situational moral disengagement: Can the effects of self-interest be mitigated? Journal of Business Ethics, 125, 267–285.

Kornblith, H. (1999). Distrusting reason. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 23, 181–196.

Kruger, J., & Gilovich, T. (1999). ‘Naïve cynicism’ in everyday theories of responsibility assessment. Journal of Personal and Social Psychology, 76, 743–753.

Kruger, J., & Gilovich, T. (2004). Actions, intentions, and self-assessment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 328–339.

Levy, N. (2003). Descriptive relativism: Assessing the evidence. The Journal of Value Inquiry, 37, 165–177.

Lewis, D. (1996). Illusory innocence? Eureka Street, 6, 35–36.

Lichtenberg, J. (2009). Famine, affluence, and psychology. In J. Schaler (Ed.), Peter singer under fire: The moral iconoclast faces his critics. Chicago: Open Court.

Lichtenberg, J. (2014). Distant strangers: Ethics, psychology, and global poverty. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Locke, J. (1690/1959). In A. C. Fraser (Ed.), An essay concerning human understanding (Vol. 2). New York: Dover Publications.

Loeb, D. (1998). Moral realism and the argument from disagreement. Philosophical Studies, 90, 281–303.

Lord, C., Lepper, M., & Preston, E. (1984). Considering the opposite: A corrective strategy for social judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 1231–1243.

McGrath, S. (2007). Moral disagreement and moral expertise. In R. Shafer-Landau (Ed.), Oxford studies in metaethics (Vol. 3). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McMahan, J. (2013). Moral intuition. In H. LaFollette (Ed.), The Blackwell guide to ethical theory (2nd ed.). Malden: Blackwell.

Miller, R. (2010). Globalizing justice: The ethics of poverty and power. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Miller, D., & Ratner, R. (1998). The disparity between the actual and assumed power of self-interest. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 53–62.

Moody-Adams, M. (1997). Fieldwork in familiar places: Morality, culture, and philosophy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Murphy, L. (2000). Moral demands in nonideal theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nado, J. (2014). Philosophical expertise. Philosophy Compass, 9, 631–641.

Nagel, T. (1986). The view from nowhere. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Narveson, J. (2013). Feeding the Hungry. In J. McBrayer & P. Markie (Eds.), Introducing ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Otteson, J. (2006). Actual ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pronin, E. (2007). Perception and misperception of bias in human judgment. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11, 37–43.

Pronin, E., Lin, D., & Ross, L. (2002). The bias blind spot: Perceptions of bias in self versus others. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 369–381.

Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of justice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Reeder, G., Pryor, J., Wohl, M., & Griswell, M. (2005). On attributing negative motives to others who disagree with our opinions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1498–1510.

Ross, L., & Ward, A. (1996). Naive realism in everyday life. In T. Brown, E. Reed, & E. Turiel (Eds.), Values and knowledge. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Schwartz, N., Sanna, L., Skurnik, I., & Yoon, C. (2007). Metacognitive experiences and the intricacies of setting people straight. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 39, 127–161.

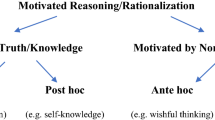

Schwitzgebel, E., & Ellis, J. (2017). Rationalization in moral and philosophical thought. In J.-F. Bonnefon & B. Tremoliere (Eds.), Moral inferences. New York: Routledge.

Scott-Kakures, D. (2000). Motivated believing: Wishful and unwelcome. Nous, 34, 348–375.

Seipel, P. (2019). Why do we disagree about our obligations to the poor?. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice 22 (1):121-136

Seipel, P. (forthcoming). Moral relativism. In M. Kusch (Ed.) Handbook to relativism.

Shafer-Landau, R. (2003). Moral realism: A defense. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sikka, S. (2012). Moral relativism and the concept of culture. Theoria, 59, 50–69.

Singer, P. (1972). Famine, affluence, and morality. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 1, 229–243.

Singer, P. (1995). How are we to live? Ethics in an age of self-interest. New York: Prometheus Books.

Singer, P. (2002). Poverty, facts, and political philosophies. Ethics and International Affairs, 16, 121–124.

Singer, P. (2009a). The life you can save: Acting now to end world poverty. New York: Random House.

Singer, P. (2009b). An intellectual autobiography. In J. Schaler (Ed.), Peter Singer under fire: The moral iconoclast faces his critics. Chicago: Open Court.

Stout, J. (2004). Democracy and tradition. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Tersman, F. (2006). Moral disagreement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thomson, J. J. (1971). A defense of abortion. Philosophy and Public Affairs, 1, 47–66.

Thomson, J. J. (1996). Moral relativism and moral objectivity. Cambridge: Blackwell.

Tong, E., & Glantz, S. (2007). Tobacco industry efforts undermining evidence linking secondhand smoke with cardiovascular disease. Circulation, 116, 1845–1854.

Unger, P. (1996). Living high and letting die: Our illusion of innocence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wedgwood, R. (2014). Moral disagreement among philosophers. In M. Bergmann & P. Kain (Eds.), Challenges to moral and religious belief. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wenzel, M. (2005). Misperceptions of social norms about tax compliance: From theory to intervention. Journal of Economic Psychology, 26, 862–883.

Williamson, T. (2011). Philosophical expertise and the burden of proof. Metaphilosophy, 42, 215–229.

Wilson, T., Centerbar, D., & Brekke, N. (2002). Mental contamination and the debiasing problem. In T. Gilovich, D. Griffin, & D. Kahneman (Eds.), Heuristics and biases. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wong, D. (1984). Moral relativity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the audience at the 2018 Joint Meeting of the South Carolina Society for Philosophy and the North Carolina Philosophical Society. I benefited from discussions with Shane Wilkins, Greg Lynch, Turner Nevitt, Xingming Hu, Carlo Davia, Joe Vukov, David Kovaks, Emily Sullivan, Stephen Grimm, and Christopher W. Gowans. Special thanks are due to Nathan Ballantyne for his encouragement and helpful comments on numerous drafts of the essay.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Seipel, P. Famine, affluence, and philosophers’ biases. Philos Stud 177, 2907–2926 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-019-01352-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-019-01352-7