Abstract

I outline and provide a solution to some paradoxes of ground.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

\(\langle \)A\(\rangle \) refers to the proposition that A. So \(\langle \)snow is white\(\rangle \) refers to the proposition that snow is white.

He discovered this puzzle about ten years later (Fine 2010).

Correia and Skiles (2017) are also inlined to take non-factive ground as basic.

The only serious attempt I know of is (Fine manuscript). He isn’t completely successful.

We interpret the grammar of ‘,’ such that lists are invariant under both permutation and repetition: so we treat A, B, C\(\ldots \), for instance, as the same list as C, B, A\(\ldots \) and A as the same list as A, A, A\(\ldots \)

This and the next clause mean I’m formulating ground as a sentential operator. This is common in the literature.

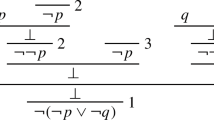

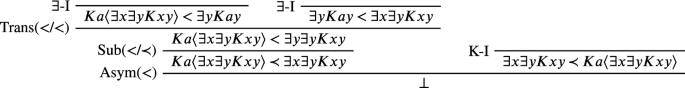

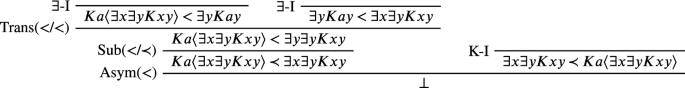

The derivation of an absurdity is:

Some people, for example (Korbmacher 2018a), formalize ground as a predicate of sentences. Currently, such systems only deal with sentences which express first-order claims. They have not yet been extended to sentences which express higher-order claims. So, such an extension might not yield a higher-order rule which generates a Krämer-like paradox. If so, taking ground to be a predicate would provide an interesting way to avoid this paradox. But how promising this option is is as yet unknown: it depends on how we should extend systems like the one in Korbmacher (2018a).

This extension of the system also puts us in a position to deal with a worry about the puzzle concerning knowledge. The worry is that the plausibility of K-I rests entirely on that of T-I. This would mean the knowledge puzzle added nothing further to the puzzle involving truth. One might think this for the following reason: suppose one endorses the claim that, generally, T\(\langle \)A\(\rangle \) strictly partially grounds Ka\(\langle \)A\(\rangle \). The instances of K-I follow from this, T-I and the transitivity of partial ground. So, one might think that these rules provide the basis for the intuition that these instances are plausible. So, if we jettison T-I, then we have no reason to endorse K-I. I’m unsure whether this is a good worry. That’s because I’m unsure what the basis of my intuitions are. But, as I said, the extension of the system allows us to deal with it. To do so, we introduce a relation, \(K^h\), which can hold between terms and wffs. We interpret \(K^htP\) as t knows that P. We then formulate a new version of the knowledge rule. This is: \(\overline{A \prec K^{h} aA}\). This, together with \(\exists \)-I\(^h\), generates absurdity. The proof parallels that in n.12: just remove all the propositional brackets, replace \(\exists \)-I for \(\exists \)-I\(^h\), and replace K-I for this new rule. There’s no obvious reason for thinking the plausibility of this rule is based on T-I. So we’ve dealt with the worry.

This exact puzzle doesn’t arise on the factive notion. But Fine (2010, 102) outlines a related one which does.

The truth schema says: \(A \leftrightarrow T\langle A\rangle \).

Kripke (1975) famously denies that they are.

However, see Rodriguez-Pereyra (2015, 525–528) for a defence of factive versions of the puzzle of the truthteller.

The factive version of T-I is: the rule: \(\frac{\hbox {A}}{\hbox {A} < \hbox {T}\langle \hbox {A}\rangle }\).

It certainly is in Korbmacher (2018b).

Woods recognizes the issue in a footnote (Woods 2017, n. 38).

There is a general question of what it is for the particular content of A to explain something. I’ve made a few suggestions to Woods. The one he liked best was contrastive. On this view, the particular content of A explains B iff there is some C such that A rather than C explains B. This is a likeable suggestion, because in the puzzle cases there is no such C. Yet it remains non-obvious to me why we should balk at there being some C such that A rather than C explains A, but not balk at A explaining A.

See Dorr (2016) for an extensive discussion.

See Correia and Skiles (2017, 19).

See Fine (2017, 685–86).

I can think of some bad reasons to reject it. Here’s one: A weakly fully grounds A but then this requires \(\exists p (A\) just is \(A \vee p)\). And there’s no such p. So you can’t guarantee everything weakly grounds itself. Here’s why this is a bad reason: I think A just is \(A \vee A\). So A itself is such a p. So we can guarantee that \(A \le A\). Of course it’s controversial that A just is \(A \vee B\) in the representational sense of ‘just is.’ This isn’t part of the system in Correia (2017a). But the rules I’ll present in the next section are inconsistent with this system anyway. So it’s hardly worrying that this claim conflicts with those rules. Here’s another bad reason: this characterization clashes with the strict ground principles we began with. For example, \(A \vee A\) just is \((A \vee (A \vee A))\). So \((A \vee A)\) weakly fully grounds A. But this conflicts with \(\vee \)-I. This is bad for much the same reason. In the next section I’ll say we should restrict rules like \(\vee \)-I. So again it’s not worrying that our characterization conflicts with such rules.

This is essentially an extension of the system presented in Lovett (2019).

These definitions are formalization of those is Fine (2012, 51–52).

Correia (2017a, 525) argues that weak partial ground is antisymmetric. This would make this conclusion untenable. But he characterizes weak full grounding quite differently to how it’s characterized Sect. 7.1 (Correia 2017a, 516). He defines weak full ground as strict ground or identity. In the singular case, he says \(A \le B\) iff \(A < B\) or A just is B. From such a definition it follows that weak partial ground is antisymmetric. So this is not one of the characterizations of weak full ground on which the solution in the text works. But on the characterizations I give in Sect. 7.1 it seems to me implausible that weak partial ground is antisymmetric. Consider the disjunction characterization. On this view A weakly partially grounds B iff there’s some p, q such that A just is \((p \vee (q \wedge B))\). B weakly partially grounds A iff there’s some \(p_1, q_1\) such that \((p_1 \vee (q_1 \wedge A))\). But this doesn’t even guarantee that A and B are materially equivalent. So it can hardly be thought to guarantee that A and B are identical. Similar remarks go for the explanatory subsumption characterization: the fact that A helps explain everything B helps explain and vice versa hardly seem to guarantee that they’re identical. So we needn’t think weak partial ground is antisymmetric. That’s not to say there isn’t an antisymmetric notion in the vicinity. Following Correia and Skiles (2017, 19), I suspect that weak full ground is antisymmetric. But this doesn’t cause any problems for the proposed solution. Thanks to a helpful referee for raising this point.

To get a satisfactory logic we do of course need to add some ancillary rules. We need at least those from Fine’s pure logic (Fine 2009). I omit these because they aren’t necessary for generating the puzzles.

Some people who like deflationary theory of truth deny there are such things as propositions. They would presumably prefer to articulate the deflationary theory some other way. Thanks to a referee for this point.

There might be other tasks for which we need representational ground. Correia (2017b), for example, suggests representational ground can help give us an account of real definition. But it’s not clear that this makes representational ground indispensable. That’s because Correia thinks we can formulate his account of real definition in terms of another notion: comparative joint-carvingness. Now he does also argue that comparative joint-carvingness and representational ground are equivalent (Correia 2017b, 65–70). But, if representational ground is paradoxical, then this seem to give us good motivation to resist these arguments.

References

Barnes, E. (2018). Symmetric dependence. In Reality and its structure. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Correia, F. (2014). Logical grounds. The Review of Symbolic Logic, 7(1), 31–59.

Correia, F. (2017a). An impure logic of representational grounding. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 46(5), 507–538.

Correia, F. (2017b). Real definitions. Philosophical. Issues, 27(1), 52–73.

Correia, F., & Skiles, A. (2017). Grounding, essence, and identity. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 98, 642–670.

deRosset, L. (2013a). Grounding explanations. Philosophers’. Imprint, 13(7), 1–26.

deRosset, L. (2013b). What is weak ground? Essays in Philosophy, 14(1), 7–18.

Dorr, C. (2016). To Be F Is To Be G. Philosophical Perspectives, 30(1), 39–134.

Fine, K. Some remarks on Bolzano on ground.

Fine, K. (2001). The question of realism. Philosophers’ Imprint, 1(1), 1–30.

Fine, K. (2009). The pure logic of ground. The Review of Symbolic Logic, 5(1), 1–25.

Fine, K. (2010). Some puzzles of ground. Notre Dame Journal of Formal Logic, 51(1), 97–118.

Fine, K. (2012). Guide to ground. In F. Correia & B. Schnieder (Eds.), Metaphysical grounding: Understanding the structure of reality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fine, K. (2017). A theory of truthmaker content II: Subject-matter, common content, remainder and ground. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 46(6), 675–702.

Glanzberg, M. (2004). A contextual-hierarchical approach to truth and the liar paradox. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 33, 27–88.

Jenkins, C. S. (2011). Is metaphysical dependence irreflexive? The Monist, 94(2), 267–276.

Korbmacher, J. (2018a). Axiomatic theories of partial ground I. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 47(2), 161–191.

Korbmacher, J. (2018b). Axiomatic theories of partial ground II: Partial ground and hierarchies of typed truth. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 47(2), 193–226.

Kripke, S. (1975). Outline of a theory of truth. The Journal of Philosophy, 72(19), 690–716.

Krämer, S. (2013). A simpler puzzle of ground. Thought: A Journal of Philosophy, 2(2), 85–89.

Lovett, A. (2019). The logic of ground. Journal of Philosophical Logic. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10992-019-09511-1.

Parsons, C. (1974). The liar paradox. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 3(4), 381–412.

Peels, R. (2013). Is omniscience impossible? Religious Studies, 49(04), 481–490.

Rasmussen, J., Cullison, A., & Howard-Snyder, D. (2013). On whitcomb’s grounding argument for atheism. Faith and Philosophy, 30, 198–204.

Rodriguez-Pereyra, G. (2015). Grounding is not a strict order. Journal of the American Philosophical Association, 1(03), 517–534.

Rosen, G. (2010). Metaphysical dependence: Grounding and reduction. In Modality: Metaphysics, logic and epistemology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schaffer, J. (2009). On what grounds what. In Metametaphysics: New essays on the foundations of ontology (pp. 347–383). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Thompson, N. (2016). Metaphysical interdependence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Whitcomb, D. (2012). Grounding and omniscience. In Oxford studies in philosophy of religion IV (pp. 173–201). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Woods, J. (2017). Emptying a paradox of ground. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 47, 631–648.

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank Cian Dorr, Kit Fine, Stephen Krämer, Marko Malink and an anonymous reviewer for helpful comments on this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lovett, A. The puzzles of ground. Philos Stud 177, 2541–2564 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-019-01325-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-019-01325-w