Abstract

I argue that fallibilism, single-premise epistemic closure, and one formulation of the “knowledge-action principle” are inconsistent. I will consider a possible way to avoid this incompatibility, by advocating a pragmatic constraint on belief in general, rather than just knowledge. But I will conclude that this is not a promising option for defusing the problem. I do not argue here for any one way of resolving the inconsistency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Schroeder (2012) attributes the term “pragmatic encroachment” to Jonathan Kvanvig.

Fantl and McGrath formulate this principle in terms of “justified belief” rather than knowledge. For the sake of simplicity, I use “know.”

Fantl and McGrath (2009, p. 11).

Hawthorne (2013, p. 43).

Fantl and McGrath (2009, p. 11).

Fantl and McGrath (2009, p. 13).

Hawthorne (2004, p. 33)

This counterexample derives ultimately from Makinson (1965).

For instance, do I actually competently deduce the relevant conjunction?

Hawthorne (2013, p. 34).

Hawthorne (2004, p. 39).

Hawthorne (2013, p. 45).

I am grateful to Troy Cross for this point.

We also redistribute probabilities. Fortunately, all of the calculations in the present paper can be approximated by ignoring this redistribution.

Read EU(A |p) as “The expected utility of A given p.”

I leave this as an exercise to the reader.

I have not made p and q probabilistically independent for two reasons. First, whether or not p and q are independent does not affect my argument—none of the closure principles I consider require that p and q are independent. Second, it is a simple task to make a matrix with the same problematic consequences as this one, but with probabilistically independent p and q. (We would just have to adjust the utilities proportionally to our adjustment of the probabilities.) The math is simplified as it is and independence would just muddy the waters.

It is interesting to note that this decision problem can be adapted to show that KAP* is not closed with respect to modus ponens. Cross out the second column of the matrix and redistribute the probabilities accordingly. Now the proposition \(p \rightarrow q\) has probability 1. Calculations like those above show that the subject could know that p, know that \(p \rightarrow q\), competently deduce q from p, etc. yet not know that q. So, KAP* violates closure with respect to modus ponens.

Stanley (2005, p. 94).

Remember our formulation of single-premise closure: if one knows that p, and competently deduces q from p, thereby coming to believe q, while retaining one’s knowledge that p, one comes to know that q.

It is unclear whether Fantl and McGrath’s principle (or others) can actually do this. Our subject might simply irrationally treat q as a motivating reason for \(\phi\)-ing for all relevant \(\phi\), despite the fact that she is not rational to “act as if q.” (Perhaps she simply doesn’t realize the stakes associated with q.) I am grateful to an anonymous reviewer here.

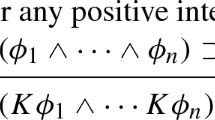

I focus on Distribution here, but similar considerations apply to Addition Closure.

See for example, Williamson (2000).

We can also assume that the content of “\(p \wedge q\)” is informative, conversationally appropriate, etc. so that no other norms of assertion are violated.

I suspect that denying closure is an inappropriate response to the considerations presented in this paper. To use Dretske’s (2013) terminology, the most plausible potential cases of closure failure involve inferences from a “lightweight” proposition (such as “here are hands”) to a “heavyweight” proposition (such as “I am not a handless brain in a vat”). But the potential case of closure failure presented above lacks this feature. I am grateful to Marc Alspector-Kelly for this point.

For example, Fantl and McGrath (2009, p. 66) endorse the principle (“KJ”) that “If you know that p, then p is warranted enough to justify you in \(\phi\)-ing for any \(\phi\),” where \(\phi\) does not have to be an available action. This principle is not subject to the criticism I presented for KAP*—By KJ, the subject in Sect. 5 does not know \(p \wedge q\) because the proposition is not warranted enough to justify her in doing this particular \(\phi\): concluding q from \(p \wedge q\) and using q in practical reasoning. I am grateful to an anonymous referee for this observation.

References

DeRose, K. (1992). Contextualism and knowledge attributions. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 52, 913–929.

Dretske, F. (2013). The case against closure. In M. Steup, J. Turri, & E. Sosa (Eds.), Contemporary debates in epistemology (2nd ed., pp. 27–39). Malden, MA: Wiley.

Fantl, J., & McGrath, M. (2002). Evidence, pragmatics, and justification. The Philosophical Review, 111(1), 67–94.

Fantl, J., & McGrath, M. (2009). Knowledge in an uncertain world. New York: OUP.

Ganson, D. (2008). Evidentialism and pragmatic constraints on outright belief. Philosophical Studies, 139, 441–458.

Hawthorne, J. (2004). Knowledge and lotteries. New York: OUP.

Hawthorne, J. (2013). The case for closure. In M. Steup, J. Turri, & E. Sosa (Eds.), Contemporary debates in epistemology (2nd ed., pp. 40–55). Malden, MA: Wiley.

Hawthorne, J., & Stanley, J. (2008). Knowledge and action. The Journal of Philosophy, 105(10), 571–590.

Makinson, D. (1965). The paradox of the preface. Analysis, 25(6), 205–207.

Nozick, R. (1981). Philosophical explanations. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Ross, J., & Schroeder, M. (2014). Belief, credence, and pragmatic encroachment. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 88(2), 259–288.

Schroeder, M. (2012). Stakes, withholding, and pragmatic encroachment on knowledge. Philosophical Studies, 160, 265–285.

Stanley, J. (2005). Knowledge and practical interests. New York: OUP.

Weatherson, B. (2005). Can we do without pragmatic encroachment? Philosophical Perspectives, 19(1), 417–443.

Williamson, T. (2000). Knowledge and its limits. New York: OUP.

Acknowledgments

This paper benefitted greatly from comments and conversation with Troy Cross, Dan Dolson, Wes Siscoe, and an audience at Western Michigan University. Most of all, I am grateful to Marc Alspector-Kelly for both introducing me to these topics and providing several sets of helpful comments on early drafts of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zweber, A. Fallibilism, closure, and pragmatic encroachment. Philos Stud 173, 2745–2757 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-016-0631-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-016-0631-5