Abstract

Moderate holists like French (Collective and corporate responsibility, 1984), Copp (J Soc Philos, 38(3):369–388, 2007), Hess (The Background of Social Reality – A Survey, 2013), Isaacs (Moral responsibility in collective contexts, 2011) and List and Pettit (Group agency: The possibility, design, and status of corporate agents, 2011) argue that certain collectives qualify as moral agents in their own right, often pointing to the corporation as an example of a collective likely to qualify. A common objection is that corporations cannot qualify as moral agents because they lack free will. The concern is that corporations (and other highly organized collectives like colleges, governments, and the military) are effectively puppets, dancing on strings controlled by external forces. The article begins by briefly presenting a novel account of corporate moral agency and then demonstrates that, on this account, qualifying corporations (and similar entities in other fields) do possess free will. Such entities possess and act from their own “actional springs”, in Haji’s (Midwest Stud Philos, 30(1):292–308, 2006) phrase, and from their own reasons-responsive mechanisms. When they do so, they act freely and are morally responsible for what they do.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As a referee noted, this raises the question of how to define the membership of the collective. It is well beyond the scope of this article to address this issue in the detail it deserves, but in general: the membership consists of those agents whose actions consistently shape and are shaped by the corporate RPV (discussed below). For the most part, this will be employees of the corporation (or other qualifying collective), from top to bottom, but each type of collective has its own “gray areas.” For corporations, do long-term contractors or temporary employees count? For universities, do the students count? What about the congregants, for religious orders, or the citizens for governments? There will be many instances where it will be unclear whether an individual agent was or was not a member of a corporate entity. In such cases, the answer will turn on empirical questions about the extent to which the agent’s actions shaped and were shaped by the corporate RPV; the matter does not turn on questions of formal title or payment.

Whether in business, education, government, religion, or war.

All of these accounts were developed to address human intentionality, and I have applied them to the collective context without modification. I have also woefully over-simplified them, in the interests of brevity: the full accounts are far more sophisticated than I have suggested here, and the claim that corporate commitments qualify on these accounts is thus more compelling. See (Hess 2014) for a more extensive discussion.

Specifically, where Group is a group of human agents and ACME is a given corporate entity, Group constitutes ACME iff:

-

(1)

Group and ACME are spatially coincident at t; and

-

(2)

Group is in the circumstance of having members who are able to and disposed to effectively coordinate their actions in accordance with the imperatives of a particular rational point of view not (necessarily) associated with any single human agent at t; and

-

(3)

It is necessary that: if anything that has being a group of human agents as its primary-kind property is in the circumstance in which those agents are able to and disposed to effectively coordinate their actions in accordance with the imperatives of a particular rational point of view not (necessarily) associated with any single human agent at t, then there is something that has being a corporate entity as its primary-kind property that is spatially coincident with the group of human agents; and

-

(4)

It is possible that: Group exists at t and that no spatially coincident thing that has being a corporate entity as its primary-kind property exists at t (developed from Baker 2000, 2002).

(1)

-

(1)

It is not necessary that the members intend to act on the basis of the corporate commitments or know that they do so. It is only necessary that they would not, in fact, have acted as they did in the absence of the corporate commitments.

These do not designate different types of corporations, but processes likely to occur at all corporations (and other collectives). Note that all three are in play at ACME.

See List and Pettit (2011) and related literature by the authors for an exhaustive discussion of the discursive dilemma. The point here is both simpler and broader, and not restricted to the technical situations they address.

None of the existing accounts from Copp (2007), French (1984), Gilbert (1992), Isaacs (2011), List and Pettit (2011), Miller (2001) acknowledges or allow for this kind of distributed decision-making, whether intentionally or unintentionally pursued by the members. It would not qualify as an act or decision of the corporate entity on their accounts, nor would the actions that flow from it. And yet it is indispensible to contemporary corporate practice. Corporate practice relies upon intense specialization to achieve its efficiencies, and it is rarely the case that everyone who needs to contribute to a decision has time to sit down and discuss the matter with everyone else who needs to contribute to the decision. Distributed decision-making solves this problem, though it (obviously) carries its own costs.

To make this more realistic, assume that each “Member” in the example is a department, and add further concerns—and additional steps—to address tax implications, public relations, supplier relationships, etc.

It does not follow that ACME’s members are not morally responsible for their own contributions to the development of the corporate RPV, or to the corporate actions that follow from it. If anything, by highlighting the many ways in which members can contribute to the development of corporate commitments, this account allows for a clearer and more encompassing discussion of the moral responsibility that the members (of all ranks) may have. See Isaacs (2011) for a general discussion of individual responsibility in such settings; see my "Collateral Responsibility", in progress, for a discussion of individual responsibility on this account.

As discussed below, if this happened then the new belief would not be a corporate belief but an external commitment imposed on the corporate entity in violation of its own commitments. The situation would be analogous to violation via brainwashing or hypnosis.

To be precise, corporate beliefs and desires “coincide” with specific member activity, in the sense established by Yablo (1992a, b). This is in the same spirit as List and Pettit’s observation that corporate commitments “supervene holistically” (List and Pettit 2011), but List and Pettit claim that commitments supervene on member preferences. On the account presented here, corporate commitments coincide with member activity regardless of member preferences. This seems preferable, as member activity is capable of generating all kinds of effective corporate commitments which have nothing to do with member preferences.

Haji also identifies a third possibility: the requirement that the agent be a “substance” and capable of “substance- or agent-causation.” It is beyond the scope of this article to adequately address the criteria for a “substance” or for agent-causation (essentially, the agent as an uncaused-cause). Haji dismisses this quickly with the simple observation that “no collective is a substance” (p. 295). I agree with his conclusion with respect to French’s and Gilbert’s accounts; these theorists make no ontological claims. It is not clear that corporate entities, as presented here, do not qualify as substances [see Halper (1995)], but that issue will have to wait.

“Suitable” here just means something like “rationally related”—that my desire to catch the ball led me to reach for the ball, or that ACME’s desire for a new product line led it to develop one.

As with all truly corporate actions, this “discovery” and the subsequent rejection, modification, or affirmation can come about via any of the three processes outlined in Sect. 2. I can only suggest the full processes here: for explicit “reasoning”, one or more members could notice the new environmental impacts and intentionally alter their own and others’ behavior in response, motivated and guided in doing so at least in part by existing corporate commitments. (If they notice but take no external action at all, the member has “discovered” but ACME has not.) For the less explicit processes (distributed or cultural): without any member necessarily intending to do so or noticing that they have, the corporation itself amasses information—available to anyone who seeks it, inside or outside—documenting the environmentally destructive consequences of its new behaviors. As different kinds of costs accumulate, various members could respond piecemeal and (over time) the corporate entity could once again develop a habit of good environmental practice.

This would be extremely unusual. New CEOs and other members of upper management do make changes, of course, but they do it gradually, and the process involves an enormous amount of negotiation with the existing commitments and structures of the corporation.

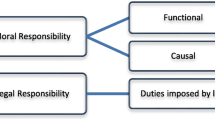

ACME would remain legally responsible in this situation. Questions of corporate moral agency and responsibility are grounded in metaphysics, not legal practice, and as previously noted legal status and implications are irrelevant.

I should note that, like Haji, McKenna concludes in his (2006) that collectives probably cannot meet his standards. It is beyond the scope of this article to fully address his further concerns but—again, like Haji—most of the difficulties are specific to the accounts from Gilbert and French.

See Hess 2011 for a more detailed discussion of the corporate “first person perspective”.

I do not believe that any of the holist accounts listed in no. 9 above can answer this objection, specifically because (as previously noted) they do not recognize the unintentional decision-making processes described in Sect. 2. The more individualistic accounts from Gilbert and Miller are generally ill-suited to addressing this kind of large scale action, as they themselves acknowledge (Gilbert 1992; Miller 2001) See Hess 2011 for a more extended discussion of corporate “thought”.

There is undoubtedly more to my deliberating than the simple firing of neurons, but that would take us too far afield.

References

Baker, L. R. (2000). Persons and bodies: A constitution view. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baker, L. R. (2002). Précis of persons and bodies: A constitution view. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 64(3), 592–598.

Copp, D. (2007). The collective moral autonomy thesis. Journal of Social Philosophy, 38(3), 369–388.

Dennett, D. C. (1989). The intentional stance. Cambridge: The MIT press.

Dennett, D. C. (1991). Real patterns. The Journal of Philosophy, 88(1), 27–51.

Dretske, F. I. (1988). Explaining behavior: Reasons in a world of causes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dretske, F. (1993). Mental events as structuring causes of behavior. In J. Heil & A. Mele (Eds.), Mental causation (pp. 121–136). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

French, P. A. (1984). Collective and corporate responsibility. New York: Columbia University Press.

Gilbert, M. (1992). On social facts. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Haji, I. (2006). On the ultimate responsibility of collectives. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 30(1), 292–308.

Halper, E. (1995). The substance of aristotle’s ethics. In S. May (Ed.), The Crossroads of norm and nature: Essays on aristotle’s ethics and metaphysics (pp. 3–28). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Hess, K. M. (2011). The modern corporation as moral agent: The capacity for thought and a first-person perspective. Southwest Philosophy Review, 26(1), 61–69.

Hess, K. M. (2013). Missing the forest for the trees: The theoretical irrelevance of shared intentions. In M. Schmitz, B. Kobow, & B. Schmid (Eds.), The Background of Social Reality – A Survey. Springer: New York, NY.

Hess, K. M. (2014). Because they can: The basis for the moral obligations of (certain) collectives. Midwest Studies in Philosophy (forthcoming).

Isaacs, T. (2006). Collective moral responsibility and collective intention. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 30(1), 59–73.

Isaacs, T. L. (2011). Moral responsibility in collective contexts. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

List, C., & Pettit, P. (2011). Group agency: The possibility, design, and status of corporate agents. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mäkelä, P. (2007). Collective agents and moral responsibility. Journal of Social Philosophy, 38(3), 456–468.

Marcus, R. B. (1991). Some revisionary proposals about belief and believing. In B. Gordon (Ed.), Causality, method, and modality (pp. 143–173). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

McKenna, M. (2006). Collective responsibility and an agent meaning theory. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 30(1), 16–34.

Miller, S. (2001). Social action: A teleological account. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Miller, S. (2006). Collective moral responsibility: An individualist account. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 30(1), 176–193.

Miller, S., & Makela, P. (2005). The collectivist approach to collective moral responsibility. Metaphilosophy, 36(5), 634–651.

Rovane, C. A. (1998). The bounds of agency: An essay in revisionary metaphysics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Velasquez, M. G. (1983). Why corporations are not morally responsible for anything they do. Business & Professional Ethics Journal, 2(3), 1–18.

Yablo, S. (1992a). Cause and essence. Synthese, 93(3), 403–449.

Yablo, S. (1992b). Mental causation. The Philosophical Review, 101(2), 245–280.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hess, K.M. The free will of corporations (and other collectives). Philos Stud 168, 241–260 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-013-0128-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-013-0128-4