Abstract

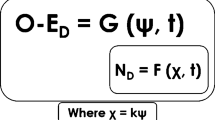

Theories of mind draw on processes that represent mental states and their computational connections; simulation, in addition, draws on processes that replicate (Heal 1986) a sequence of mental states. Moreover, mental simulation can be triggered by input from imagination instead of real perceptions. To avoid confusion between mental states concerning reality and those created in simulation, imagined contents must be quarantined. Goldman bypasses this problem by giving pretend states a special role to play in simulation (Goldman 2006). We argue that this path leads to the resurgence of the threat of collapse (Davies 1994), diluting the principled distinction between simulation and theory use. Exploration of a related method of real-mental states operating in a pretend mode leads to a factually untenable model. Our main goal here is to raise this problem as a challenge for Goldman’s reconfigured simulation theory. Only at the end we will briefly sketch a possible alternative way of quarantine that preserves the replicative element of simulation and avoids collapse. Figure 1 provides a guide to our argument.

Structure of argument

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We exclude from our discussion here a more primitive form of simulation that does not involve any imaginatory processes, which Goldman calls ‘low level’ mindreading. We suspect, however, that much of what we say can be extended to these cases.

To prevent misunderstanding: the fact that in this rendition of my states I am only in a single belief state is not critical (it just helps illustrate the difference more clearly). We could analyse our thinking as a transition between belief states: BEL [P believes [psychopath knocks on her door] ⇒ BEL [P believes [psychopath will come in], etc. The critical difference to the real case in <1.1> and, as we will see later, the replicative element of simulation is that this sequence of belief-states is not a replication of states I would actually be going through when put in this kind of situation. Nor would I have the complex belief depicted in<1.2>.

This process need not be based on a conscious and effortful act of imagination but might occur unconsciously and automatic as in some cases of automatic empathy (e.g. De Vignemont and Singer 2006).

We put no further constraints here on the type of process involved; it may be either a factual reasoning mechanism, a decision making mechanism (see Goldman 2006 p. 27), or any other type of process.

This would be a special case of representation in so far as the representational vehicle and the representational target share a common structure. It is nevertheless a representational process since this common structure exists only for a representational purpose.

With this capitalisation of “hearing” we make explicit that the imagination should be from a first-person perspective, capturing Goldman’s notion of “enactment imagination” (p. 47), where one imagines hearing the knock and not from a third-person perspective where one imagines that one hears the knock, i.e. imagines oneself as a person within ear shot of the knock on the door.

Goldman (Goldman 2006, e.g. p. 29) uses this term in a more specific way: “… it is often important to the success of a simulation for the attributor to quarantine his own idiosyncratic desires and beliefs (etc.) from the simulation routine”.

In making this claim, we do not deny that we can pretend to be in all sorts of mental states, nor do we challenge Goldman’s claim that such pretence-states are created by a form of imagination that he calls “enactment imagination” (Goldman 2006, p. 47 and 149ff.) It is not the existence or the nature of such states that we call into question, but the role that those states are supposed to play in a simulationist account of mind-reading.

Off-line is Stich and Nichols’ (1995, p. 91) term: “The basic idea of what we call the ¨off-line simulation theory¨ is that in predicting and explaining people’s behaviour we take our own decision-making system ¨off-line¨, supply it with ¨pretend¨ inputs that have the same content as the beliefs and desires of the person whose behaviour we are concerned with, …”. As defined in this passage, “off-line” simulation would cover the case we are considering here, but the authors’ use also encompasses the use of pretend states (Nichols and Stich 2003, pp. 39–40).

Although (Goldman 2006, p. 46) also distances himself from Nichols and Stich’s proposal, his pretend states are still modifications of the functional states while on the proposal sketched here they would be normal beliefs and desires with modified contents.

References

Davies, M. (1994). The mental simulation debate. Proceedings of the British Academy, 83, 99–127.

Dennett, D. C. (1987). The intentional stance. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, A Bradford Book.

De Vignemont, F., & Singer, T. (2006). The empathic brain: How, when and why? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10, 435–441.

Evans, F. J. (1980). Posthypnotic amnesia. In G. D. Burrows & L. Dennerstein (Eds.), Handbook of hypnosis and psychosomatic medicine (pp. 85–103). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Goldman, A. I. (1989). Interpretation psychologized. Mind and Language, 4, 161–185.

Goldman, A. I. (2006). Simulating minds: The philosophy, psychology, and neuroscience of mindreading. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gordon, R. M. (1995). Simulation without introspection or inference from me to you. In M. Davies & T. Stone (Eds.), Mental simulation: Evaluations and applications (pp. 53–67). Oxford: Blackwell.

Gordon, R. M. (2007). Ascent routines for propositional attitudes. Synthese, 159, 151–165.

Heal, J. (1986). Replication and functionalism. In J. Butterfield (Ed.), Language, mind, and logic (pp. 135–150). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jackson, F. (1999). All that can be at issue in the theory-theory simulation debate. Philosophical Papers, 28, 77–96.

Jackson, J. H. (1951). Selected writings of John Hughlings Jackson. New York: Basic Books.

Kirsch, I., Silva, C. E., Carone, J. E., Johnston, J. D., & Simon, B. (1989). The surreptitious observation design: An experimental paradigm for distinguishing artifact from essence in hypnosis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 98, 132–136.

Kühberger, A., Schulte-Mecklenbeck, M., & Perner, J. (2002). Framing decisions: Hypothetical and real. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 89, 1162–1175.

Leslie, A. M. (1987). Pretense and representation: The origins of “Theory of Mind”. Psychological Review, 94, 412–426.

Nichols, S., & Stich, S. P. (2003). Mindreading: An integrated account of pretence, self-awareness, and understanding other minds. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Perner, J. (1991). Understanding the representational mind. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, A Bradford Book.

Perner, J. (1994). The necessity and impossibility of simulation. Proceedings of the British Academy, 83, 145–154.

Perner, J. (1996). Simulation as explicitation of predication-implicit knowledge about the mind: Arguments for a simulation-theory mix. In P. Carruthers & P. K. Smith (Eds.), Theories of theories of mind (pp. 90–104). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Perner, J., Gschaider, A., Kühberger, A., & Schrofner, S. (1999). Predicting others through simulation or by theory? A method to decide. Mind and Language, 14, 57–79.

Perner, J., & Kühberger, A. (2003). Putting philosophy to work by making simulation theory testable: The case of endowment. In Ch. Kanzian, J. Quitterer, & E. Rungaldier (Eds.), Persons. An interdisciplinary approach (pp. 101–116)—Proceedings of the 25th International Wittgenstein Symposium (Kirchberg am Wechsel, Austria, 11–17 August, 2002. Wien: öbv-hpt Verlagsgesellschaft.

Perner, J., & Kühberger, A. (2005). Mental simulation: Royal road to other minds? In B. Malle & S. Hodges (Eds.), Other minds: An interdisciplinary examination (166–181). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Schabus, M., Gruber, G., Parapatics, S., Sauter, C., Klosch, G., Anderer, P., et al. (2004). Sleep spindles and their significance for declarative memory consolidation. Sleep, 27, 1479–1485.

Stich, S., & Nichols, S. (1995). Second thoughts on simulation. In T. Stone & M. Davies (Eds.), Mental simulation: Evaluations and applications (pp. 87–108). Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Ward, N. S., Oakley, D. A., & Frackowiak, R. S. J. (2003). Differential brain activations during intentionally simulated and subjectively experienced paralysis. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 8, 295–312.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bob Gordon for his constructive scepticism and invaluable help in making our argument more transparent and Toni Kühberger for moral support. The collaboration of the authors was made possible by the Austrian Science Fund projects I93-G15 “Metacognition of Perspective Differences” and I94-G15 “Levels of Self Awareness” as part of the ESF EUROCORES CNCC (Consciousness in a Natural and Cultural Context) initiative collaborative research project, “Metacognition as a precursor to self-consciousness: evolution, development, and epistemology”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Contribution to book symposium in Philosophical Studies, for Professor Alvin Goldman’s Simulating Minds.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Perner, J., Brandl, J.L. Simulation à la Goldman: pretend and collapse. Philos Stud 144, 435–446 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-009-9356-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-009-9356-z