Abstract

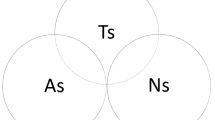

What things mean to us involves more than what they afford in a straightforward sense (e.g., motor affordances). One can think of bodily adornments, lines, or precious stones. Differently from tools like hammers, these things are used to be displayed, watched etc. The paper investigates this very important feature of human behaviour, focusing especially on the expressive possibilities, or salience, of tools. This is interpreted as an emergent property of our engagement with tools, for which tools matter to us because of what they show, not just because of what we do with them in a strict sense. A phenomenological approach is obtained by building upon Heidegger's view of tools as structured by implicit “indications” of relevance; this approach is developed by engaging with debates on mark making, stone tools, and aesthetic experience. It is argued that the salience of things is a process where indications of relevance become explicit and relatively distanced from motor affordances; this alliance of explicitness and absence of action allows for things to "resonate" in us, inviting us to see tools as invitations to imagine, think, and remember. The paper considers examples of entanglements of salience and affordances, where tools and techniques shape symbols and imaginaries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

N/A.

Notes

Affordances are invitations to act that include, but are not reducible to, motor actions like hammering. Indeed, scholars extend the concept of affordance to sociocultural forms of life, sociocultural practices, and regimes of shared attention (see, e.g., Ramstead et al., 2016). As argued by Rietveld & Kiverstein (2014), things and environments afford more than actions like sitting or grasping. In this view, the landscape of affordances humans inhabit is richer because “we are creatures that participate in sociocultural practices” (p. 326). Our ecological niche and the material environment we live in are thus shaped and sculpted by sociocultural practices. I return on the social dimension at the end of Section 1.2.

Here I follow Stambaugh’s translation of Bewandtnis as “relevance.” Wrathall (2021) translates Bewandtnis as “affordance,” and recalls other solutions, e.g., “involvement” (Macquarrie and Robinson), “functionality” (Hofstadter). He notes that “Bewandtnis has to do with the way use-objects function in a particular setting or context”; the term indicates the way worldly things are “encountered in terms of an environmentally- and agent-specific opportunity to act.”.

As Heidegger puts it (2010, p. 84/82), things are “relevant together with something else.” “To be relevant means to let something be together with something else. The relation ‘together … with …’ is to be indicated by the term reference (Verweisung).”.

I choose to translate Verweisung as “indication” instead of “reference” (as in Stambaugh’s translation).

Heidegger holds a “relational” view of human handiness as a primordial form of meaningfulness that precedes and makes possible meanings and words. This involves a rejection of internal representations, thereby marking an affinity with embodied cognition. But the account of language in Being and Time is notoriously more problematic, and Heidegger seems to hold a sort of derivative-view that is not very useful for recent debates, e.g., on enlanguaged affordances (Kiverstein & Rietveld, 2021) and enlanguaged experience (Dreon, 2024). In this article, I will make use of Heidegger’s notion of relevance to investigate the expressivity of tools. This might shed more light on some extra- or pre-linguistic aspects of the so-called scaling-up problem.

Ratcliffe & Broome (2022) distinguish between phenomenological and non-phenomenological salience. The latter means “detection,” responsiveness, and solicitation of behavior associated with neural activation; phenomenologically understood, “salience” is instead an experience in which “things appear conspicuous in one or another way without the prior involvement of active attention or explicit thought.” Salience is “thus a matter of practically engaged anticipation, something that is either integral to perceptual experience or at least intimately associated with it.” We have salience when “we are drawn to act so as to realize or avoid a possibility that it points to, a possibility that matters to us.” This definition of salience is closer to (but not identical with) what I call, more generally, relevance, while (as I will explain) I reserve salience for artifacts. My use of the terms “artifact” and “salience” is close to Dissanayake (2013), who defines “artification” as the process that “uses salience to attract attention and manipulate emotional response.” Her focus is on how we started “deliberately to ‘artify’ ordinary artifacts and behavior, shaping and enhancing them so that they were no longer ordinary, but somehow extra-ordinary.”(6, my emphasis).

“But signs are themselves initially useful things whose specific character as useful things consists of showing (Zeigen). Such signs are signposts, boundary-stones, the mariner’s storm-buoy, signals, flags, signs of mourning, and the like.” (Heidegger, 2010, p. 77/76; translation altered). Heidegger also says that “among signs there are clues, signs pointing backward as well as forward, marks, hallmarks.” (p. 78/77).

Different strands in philosophy attempt to rethink symbolic behavior as an emerging structure of perception and human–environment interactions. A recent attempt in philosophy is Dreon (2022), who draws on pragmatism and anthropology to elaborate a model of “cultural naturalism.” In cognitive archaeology, an approach inspired by Peirce’s semiotics is offered, e.g., by Garofoli (2015), Iliopoulos (2016).

For van Mazijk (2023), these three features characterize the “modern concept of symbolism” underpinning anthropological, archaeological, and philosophical discourse. I will be discussing examples of artifacts that are cognitively relevant because they are expressive of what they are to us, yet without being symbolic in this modern sense. I use terms like “pre-” or “proto-symbolic” to refer to this expressivity of things and tools.

See the debate ignited by Henshilwood and Dubreuil’s (2011) study on the South African Still Bay and Howieson’s Poort.

In this sense signs, interpreted by Malafouris as enactive structures, involve a temporal and ontological priority of the signified over the signifier (2013, p. 90).

For an overview on the concept of artifact in philosophy, see Preston (2018).

My idea of an entanglement between tools and artifacts echoes Noë’s (2023) entanglement between tools (organizational activities) and strange tools (re-organizational activities, like art). I share some concerns voiced by Gallagher, when he says—referring to Noë’s previous work (2015)— that art “is not something we employ for purposes of reorganizing the lifeworld” (2022, p. 45). In his last book, Noë claims (2023, pp. 11–12) that tools and technologies “depend on being securely integrated into patterns of organized activity,” and they are the precondition of art in the same way as straightforward talk is the precondition of irony. He argues that arts rework our habits and patterns of organization in a disruptive and creative way, using them as “raw material,” putting them “on display,” making us aware of them, changing how we see things (see Noë, 2023, pp. 20–21). I will deal with similar questions by interpreting the salience of artifacts as an enhancement, display, and transformation of the (implicit) indications of relevance constitutive of tools.

As Welton (2000, p. 369) points out, for both Husserl and Heidegger the concept of indication is the key to the notion of the world as horizon. But Welton also stresses some important differences between the two authors. For Welton, in Husserl “identity” and “similarity” are primary, while Heidegger’s Verweisung is a “constant movement of deferring” where identity results from the things’ position in a holistic context.

It might be helpful to establish a parallel between the phenomenological concept of indication and the semiotic notion of indexical relations as this is employed by archaeologists and anthropologists. However, it is beyond the scope of this article to assess synergies and contrasts between phenomenological and semiotic accounts of human life as involving relations of contiguity and contextuality. On the notion of indexicality as the transcendental structure of the lifeworld in Husserl, see Dzwiza-Ohlsen (2019). D’Angelo (2020) also argues for a “semiotic” structure of perception in Husserl.

On direct social perception of others, see Gallagher (2020, pp. 121 ff.).

Cf. the examples discussed by van Dijk and Rietveld (2017, p. 2).

One might object that in his later writings, Heidegger views things as artifacts rather than tools, as when he talks about the jug’s “thinging” (Heidegger, 1994, pp. 13ff.). However, I think his analysis still overlooks the question of whether and how the jug’s “thinging” is triggered or enhanced by salient features like colors or by other features that are not, strictly speaking, relevant to the affordances of the tool (I will return to this later).

Kee (2020, Section 4) speaks of “weak imagination,” referring to sensorimotor “images” triggered by tools. Both words (and signs) and tools pose “horizorns of virtuality,” because they “can direct us imaginatively and memorially towards what is not and cannot be presented in actuality.” In his view, there are differences in degrees, rather than kinds, between signs and tools. I recognize that both things and signs are useful things, and thus they are part of contexts of relevance, but it is my strategy here to emphasize the differences between the two.

As Leroi-Gourhan has it, “We are again and again available for new forms of action, our memory transferred to books, our strength multiplied in the ox, our fist improved in the hammer” (1993, p. 246).

Renfrew (2009, chapter 6) observes that precious metals like gold and silver “do not really possess properties that make them exceptionally useful.” Their “‘use value’ is not particularly high,” while “their ‘exchange value’ arises from what is considered to be their desirability.” The value of such materials has to do with the fact they are not “easily obtainable in large quantities.” However, as Renfrew rightly stresses, “rarity alone is not enough,” because “there are many minerals rarer than gold.” Gold’s value is a “reality” only in certain societies; it is an “institutional fact.” Things, as we read, are different “in other trajectories of development, where other materials, such as jade, or the colored feathers of rare birds, held primacy of place in the local value systems.” The notion of salience I am proposing should help understand the various aspects that make us value some things as rare and not others (e.g., gold instead of feathers). The idea is that this variability depends on the indicative contexts of relevance, where environmental, social, and technological conditions predelineate some possible forms of salience while excluding others. In this perspective, the “institution” Renfrew talks about seems to be a social fact whose variability is not arbitrary or conventional, but the result of the reality in which humans act and interact.

In Garofoli’s perspective, the two examples parallel the distinction between aesthetic and indexical ornament: “While aesthetic ornaments become relevant to the eye of the observer through an emotional mechanism, indexical ornaments rely on causal connection” (2015, p. 815). Thus one can distinguish the emotional effects the gold’s shining elicit in Sally and her fellows, and the effects of the beast’s skin as indicating skills, strength, and courage. But Garofoli rightly says that gold nuggets can be “indexical of Sally’s capability of finding rare and desirable items.” (ivi.). This suggests that the two dimensions (perceptual and indexical) are entangled. More generally, one might observe the perceptual aspects (what Garofoli describes as “esthetic ornaments […] relevant to the eye of the observer through an emotional mechanism”) are entangled with indexical relations, with the two dimensions mutually influencing each other. The gold’s “shining” might depend not just on the rarity of the material, but on what that rarity means in a given context, and some aspects of the beast’s skin could be more salient than others because of some perceptual features.

The idea that things show what they (already) are is partly inspired by the notions of “methodological fetishism” (Malafouris, 2013, pp. 133 ff.) and “constitutive symbol” (Renfrew, 2009, chapter 6). With the latter, Renfrew means that things can be “symbolic of themselves.” He gives the example of stone cubes serving as weights; stone cubes are “symbolic of themselves” in the sense that the weight of the thing becomes a symbol of weight as well. The emergence of the more abstract concept of weight is thus traced back to weight as an inherent property of material things.

Following Heidegger, we can say that handiness, understood as Zuhandenheit, refers to what is experienced through “indications,” whereas Handlichkeit refers to a more literal sense of handiness (as when Heidegger talks of the “spezifische ‘Handlichkeit’ des Hammers”; 2010, p. 69/69). Evidently, the sun is “at hand” in the first sense.

That flat and rectangular surfaces afford writing is far from obvious (cf. Sommer, 2017). There is a history behind these “strange tools.” Moreover, it takes time before children learn to master surfaces as affording writing. Interestingly, in prehistory, signs and images were made on irregular surfaces, as in cave art.

One referee poses a very interesting question. One may ask whether even earlier lithic technology can be still understood as pieces of equipment in Heidegger’s sense, although they may lack what Wynn calls “displaced” and “meta-affordances.” I lean toward a positive answer, as long as, phenomenologically speaking, simpler tools would still be constituted by “indications” of usefulness. My suggestion is also that these tools would provide less potential salience and expressive affordances.

Wynn describes these meta-affordances as a “thinking about a tool, rather than simply thinking with tools” (2021b, pp. 7, 11, my emphasis). For Malafouris (2021b), the process of thinking through and with the tool has a priority, both developmental and evolutionary. His concern is that displaced and meta-affordances are not the result of mindful intentions that orient knapping gestures (from outside, teleologically, as it were), but emerge within the concrete activity of knapping. Malafouris observes that despite many important differences, the various approaches to stone tools share the assumption that mind and tool (thinking about and making tools) are separate. These approaches “identify knapping with some sort of unidirectional causal and intentional process by which the active mind imposes form […] on the passive stone” (pp. 111–112). De-emphasizing the mindfulness of this activity does not imply, however, that “Acheulean biface [do not involve] a series of complex intentions, anticipations and decisions about size, shape, symmetry, thinness and sharpness” (ibid..). The problem is how to think of these intentions and anticipations as emerging in the skilled making of the tool. And as Malafouris remarks, the very concept of intentionality is vaguely and poorly defined in archaeology. This is where phenomenology can be of help. I suggest that knapping gestures involve no explicit intention, but they do involve implicit indications of usefulness. On the importance of the phenomenological notion of intentionality in archaeology, see Mazijk (2022).

See Behnke (2018) for an interesting take on transparency, based on Husserl’s notion of Durchang.

See Heidegger’s description of the modification of unhandiness (2010, p. 73/73).

These considerations allow Brinckner (2015, p. 134) to establish a parallel between Kant’s “free play of imagination” and studies showing evidence of a connection between artworks and the activation of the Default Mode Network (DMN).

I say “must” because we expect our fellows to recognize salient and expressive patterns (like lines, images, pointers) and we expect people to recognize artifacts like flags, images, or ritual objects, handling them accordingly (e.g., as things useful for what they show).

See Severi (2018, pp. 70–78); cf. also his discussion of Wayana basketry, pp. 237ff.

References

Behnke, E. A. (2018). On the deep structure of world-experiencing life. Etudes phénoménologiques-Phenomenological. Studies,2, 21–45.

Brincker, M. (2015). The aesthetic stance: On the conditions and consequences of becoming a beholder. In A. Scarinzi (Ed.), Aesthetics and the embodied mind: Beyond art theory and the cartesian mind-body dichotomy. Springer.

D’Angelo, D. (2020). Zeichenhorizonte. Semiotische Strukturen in Husserls Phänomenologie der Wahrnehmung. Springer.

Davis, W. (1986). The origins of image making. Current Anthropology,27(3), 193–215.

De Marrais, E., Castillo, L. J., & Earle, T. (1996). Ideology, materialization, and power strategies. Current Anthropology,37(1), 15–31.

Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience. Perigee Books.

Dissanayake, E. (2013). Genesis and development of “Making Special”: Is the concept relevant to aesthetic philosophy? Rivista di estetica, 54.

Dreon, R. (2022). Human landscapes. Contributions to a pragmatist anthropology. SUNY.

Dreon, R. (2024). Enlanguaged experience. Pragmatist contributions to the continuity between experience and language. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences. Special issue “Pragmatism and Enactivism”. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-023-09950-x

Dzwiza-Ohlsen, E. (2019). Die Horizonte der Lebenswelt. Sprachphilosophische Studien zu Husserls 'erster Phänomenologie der Lebenswelt. Brill.

Gallagher, S. (2011). Aesthetics and kinaesthetics. In J. Krois, & H. Bredekamp (Eds.), Sehen und Handeln. Akademie Verlag.

Gallagher, S. (2020). Action and interaction. OUP.

Gallagher, S. (2022). The unaffordable and the sublime. Continental Philosophy Review,55, 431–445.

Garofoli, D. (2015). Do early body ornaments prove cognitive modernity? A critical analysis from situated cognition. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences,14(4), 803–825.

Guss, D. M. (1989). To weave and sing: Art, symbol, and narrative in the South American Rainforest. University of California Press.

Heidegger, M. (1994). Ga 79. Bremer und freiburger vorträge, edited by Petra Jaeger. Klostermann.

Heidegger, M. (2001). The fundamental concepts of metaphysics: World, finitude. Indiana University Press.

Heidegger, M. (2010). Being and time. State University of New York Press.

Henshilwood, C. S., & Dubreuil, B. (2011). The Still Bay and Howiesons Poort, 77–59 ka: Symbolic material culture and the evolution of the mind during the African Middle Stone Age. Current Anthropology,52(3), 361–380.

Iliopoulos, A. (2016). The evolution of material signification: Tracing the origins of symbolic body ornamentation through a pragmatic and enactive theory of cognitive semiotics. Signs and Society,4(2), 244–277.

Kee, H. (2020). Horizons of the word: Words and tools in perception and action. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences,19, 905–932.

Kiverstein, J., & Rietveld, E. (2021). Scaling-up skilled intentionality to linguistic thought. Synthese,198(Suppl 1), 175–194.

Malafouris, L. (2013). How things shape the mind: A theory of material engagement. MIT Press.

Malafouris, L. (2021a). Mark making and human becoming. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 28, 95–119.

Malafouris, L. (2021b). How does thinking relate to tool making? Adaptive Behavior,29(2), 107–121.

Noë, A. (2015). Strange tools. Art and human nature. Hill and Wang.

Noë, A. (2023). The entanglement: How art and philosophy make us what we are. Princeton University Press.

Preston, B. (2018). Artifact. In E. N. Zalta, & U. Nodelman (Eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2022 Edition).

Ramstead, M. J. D., Veissière, S. P. L., & Kirmayer, L. J. (2016). Cultural affordances: Scaffolding local worlds through shared intentionality and regimes of attention. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1–21.

Ratcliffe, M. & Broome, M. (2022). Beyond ‘Salience’ and ‘Affordance’: Understanding anomalous experiences of significant possibilities. In Archer, S. (Ed.), Salience. Routledge .

Renfrew, C. (2009). Prehistory: the making of the human mind. Modern Library.

Rietveld, E., & Kiverstein, J. (2014). A rich landscape of affordances. Ecological Psychology,26(4), 325–352.

Severi, C. (2018). Capturing imagination. Hau Books.

Sommer, M. (2017). Von der Bildfläche. Suhrkamp Verlag.

Sperber, D. (2007). Seedless grapes: Nature and culture. In S. Laurence & E. Margolis (Eds.), Creations of the mind: Theories of artifacts and their representation. Oxford University Press.

van Dijk, L. & Rietveld, E. (2017). Foregrounding sociomaterial practice in our understanding of affordances: The skilled intentionality framework. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1–12

van Mazijk, C. (2022). How to dig up minds: The intentional analysis program in cognitive archaeology. European Journal of Philosophy, 1–15.

van Mazijk, C. (2023). Symbolism in the middle palaeolithic: A phenomenological account of practice-embedded symbolic behavior. In Thomas Wynn, Karenleigh A. Overmann, and Frederick L. Coolidge (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Cognitive Archaeology, 1129–1147.

Vara Sánchez, C. (2022). Enacting the aesthetic: A model for raw cognitive dynamics. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences,21, 317–339.

Welton, D. (2000). The horizons of transcendental phenomenology. Indiana University Press.

Wrathall, M. A. (2021). Affordance (Bewandtnis). In M. A. Wrathall (Ed.), The Cambridge Heidegger Lexicon. Cambridge University Press.

Wynn, T. (2021). Ergonomic clusters and displaced affordances in early lithic technology. Adaptive Behavior, 29(2), 181–195.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to two anonymous referees for their helpful comments.

Funding

Part of this research was supported by the Austrian Agency for International Cooperation in Educa-tion & Research (OeAD-GmbH), Ernst Mach Grant (ICM-2020–00124).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Fabio Tommy Pellizzer is the sole author of this article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

N/A.

Informed consent

N/A.

Human participants and/or animals

N/A.

Competing interests

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Pellizzer, F.T. The salience of things: toward a phenomenology of artifacts (via knots, baskets, and swords). Phenom Cogn Sci (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-024-09986-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-024-09986-7