Abstract

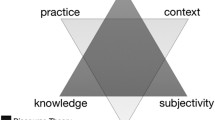

This article argues that phenomenological sociology has great potential to provide a strong theoretical support to the Sociocognitive Approach (SCA) in Critical Discourse Studies. SCA is interested in the interconnections between knowledge, discourse and society while placing subjectivity in the centre of its framework. It looks into the correlative relationship between personal- and socially shared knowledge, and the significance of these correlations to discourse production and interpretation. Analogously, phenomenological sociology explores the interrelated structures of subjectivity, knowledge and the social world. It systematically analyses the conditions and forms of intersubjective understanding and the mutually constitutive relationship between subjective- and objective knowledge. Given the considerable overlap between the subject matter of phenomenological sociology and that of SCA, the purpose of the article is to draw the attention of critical discourse analysts to a neglected but extremely resourceful field. Following a brief introduction to SCA, the article will address some of SCA’s key concepts in conjunction with the phenomenological-sociological insight.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Critical Discourse Studies, also known as Critical Discourse Analysis, is a multi-methodical and multidisciplinary field interested in the discursive manifestation and reproduction of dominance, social control, power abuse, and of social inequalities. It is primarily interested in discourses produced by social actors who control public discourse, such as the political elite, business corporations or the media. Critical Discourse Studies takes discourse as a form of social practice and analyses its relationship with the social structures by which it is shaped. Critical discourse analysts typically inquire about, for example, the discursive legitimation and persuasion strategies of right-wing populist parties, and the impact of anti-immigrant/racist discourses on the community in the prevailing socio-political context (Wodak and Meyer 2015; Van Dijk 2011, 2015a).

Within the overall framework of Critical Discourse Studies, the Sociocognitive Approach (hereinafter SCA) developed by Teun A. van Dijk focuses on the cognitive aspects of discourse production and comprehension (Van Dijk 2014a, b, 2015a, 2018). Van Dijk argues there is no direct or linear correspondence between discourse structures and social structures but discourses function through a cognitive interface: “the mental representations of language users as individuals and as social members” (Van Dijk 2015a p. 64). As Van Dijk points out, although discourse is socially conditioned and impacts upon the functioning of the society, both the formulation and interpretation of discourse is the aggregate function of the participants’ underlying cognitive processes, personal- and socially shared knowledge:

Discourse is thus defined as a form of social interaction in society and at the same time as the expression and reproduction of social cognition. Local and global social structures condition discourse but they do so through the cognitive mediation of the socially shared knowledge, ideologies and personal mental models of social members as they subjectively define communicative events as context models. (Van Dijk 2014a, p. 12)

SCA’s aim is (1) to track down and map the network of knowledge, beliefs, prejudices, attitudes that are directly or indirectly operationalised and triggered by individuals when producing and interpreting discourse, and (2) explain how that cognitive apparatus actually determine discourse structures and their interpretation in a particular communicative situation. Using the example above, SCA would be interested in why leaders of right-wing political parties address their supporters in the way in which they do, and how people make sense of such discourse.

SCA is widely applied by critical discourse scholars due to its broad and integrative perspective. Van Dijk emphasizes that the framework he offers is not a method; it does not prescribe a step-by-step procedure for discourse analysis (Van Dijk 2014a, p. 10). Rather, it draws on a multitude of methods and concepts from wide ranging disciplines, such as social psychology, cognitive psychology, anthropology, sociolinguistics and sociology, all of which are instrumental in understanding the role of knowledge in discourse production and comprehension in a given society. Although SCA is, perhaps, the most comprehensive of its kind, one might wonder why phenomenological sociology, i.e. Alfred Schutz’s phenomenologically founded sociology has gone off the radar. SCA defines itself as a “particular application” of the social constructionist tradition in social theory for that matter (Van Dijk 2018, p. 28). When setting the scene for SCA, Van Dijk maintains: “it is not the social situation that influences (or is influenced by) discourse, but the way the participants define such a situation” (Van Dijk 2008, p. x). Although Van Dijk notes that this thesis would be obvious for phenomenological sociologists, he does not explain what he means by this, nor does he draw on phenomenological sociology in the forthcoming discussion. Nevertheless, the central thesis of SCA, in fact, relates to the most basic problems of phenomenological sociology: intersubjective understanding, the relationship between subjective and objective knowledge, and our own constitutive role in the construction of social meaning, situations, i.e. social reality. SCA also draws on Conversation Analysis, a field that evolved from Harold Garfinkel’s ethnomethodology, which was predominantly based on Schutz’s phenomenological sociology. However, the purpose of this article is not to trace back certain concepts of SCA to phenomenological sociology. Rather, it draws on various concepts developed by Schutz and his successors, Thomas Luckmann and Peter Berger, that are relevant and might be productively integrated into Van Dijk’s framework. Following a brief introduction to SCA, the article will discuss some of the key concepts used by SCA and introduce their quasi-counterpart (at least complement) in phenomenological sociology. It is out of scope to provide a thorough introduction to Schutz’s framework, nor is my list of relevant concepts discussed below by any means comprehensive. I offer just one alternative selection; many others are possible, both in terms of Van Dijk’s framework and the corresponding literature of phenomenological sociology.

However, it would not be a far-fetched objection against my proposal if one argued that phenomenological sociology hardly has anything to offer for SCA, as its epistemological grounding is fundamentally distinct from that of the latter. Although the second part of this concern would be difficult to argue with, it does not necessarily imply incompatibility (Gallagher 1997, 2012). While empirical science takes for granted the object of its investigation (and that it can be investigated and understood), the phenomenological perspective is situated in a transcendental dimension and focused on the a priori conditions of how acquiring this knowledge of the natural/social world is, in the first place, possible (Zahavi 2019, pp. 44–55; 2004; Gurwitsch 1978, Natanson 1973). Phenomenology “probes” the meaning and validity of empirical facts (Natanson 1973, pp. 34–35), and shed light on the “intrinsic” characteristics of experience and understanding (Gallagher and Zahavi 2012, pp. 1–11). This is why Zahavi argues that positive sciences in general, and cognitive sciences in particular, can benefit from phenomenology, because phenomenology can “elucidate” and clarify the theoretical concepts and assumptions about perception and consciousness made by the former (Zahavi 2004). Taking this argument as a point of departure, the article provides an insight into why phenomenological sociology is relevant to, and could potentially be operationalised by, SCA contributing to its already existing strengths.

There have already been attempts to integrate phenomenological sociology and discourses studies (Keller et al. 2018). This can sensibly be done within the framework of SCA nonetheless, developing a separate approach is not necessarily warranted.

2 Intersubjective understanding and the problem of intended meaning

2.1 SCA

To genuinely understand why a particular speech or text is structured in the way it is, researchers need to reconstruct the motives, interests, intentions and goals of the speaker. Conversely, to understand why and how discourse influences social actors as its audience, it is crucial to clarify why and how the content is relevant and comprehensible to the receiver. To put it simply, the puzzle SCA is interested in is what the speaker has in mind and how it is decoded by the receiver. Van Dijk argues that participants of communicative situations, for an effective interaction, need to “read” each other’s mind in a metaphorical sense. To understand actions, including communicative actions, an intention has to be “attributed” to the observed conducts of the actors (Van Dijk 2012b). Speakers adjust their style, selection of words to the presumed interests, relevance and knowledge of the receiver to make sure their intention is intelligible to the latter. However, as Van Dijk notes, intentions themselves are not “observable”; they can only be, more or less accurately, “inferred” by the receiver (Van Dijk 2012a, b). It generally holds that both the speaker and the receiver construct subjectively meaningful mental models of one another’s intentions, identity, knowledge and of the entire setting to decrypt each other’s messages and navigate in the communicative situation (Van Dijk 2012b, 2015b).

2.1.1 Mental models

As Van Dijk maintains, mental models “define and control our everyday perception and interaction in general and the production and comprehension of discourse in particular” (Van Dijk 2014a, p. 49). We create mental models based on our past experiences stored in the Episodic or Autobiographical Memory. Mental models are “subjective representations of events or situations” with a schematic structure allowing us to categorise and identify ongoing experiences. This subjective representation also consists of the particular and personal emotions, opinions, sounds, gestures, visions accompanying the situation in which the experience unfolds (Van Dijk 2018). Van Dijk points out that the significance of a car, for example, varies when driving for pleasure and when cycling in traffic. Van Dijk calls this phenomenon “the multi-modal nature of knowledge” which derives from various emotions and sensory experiences (Van Dijk 2012a). Navigating in the communicative situation, participants dynamically draw on and “update” their mental models, discourse thus becomes subjectively meaningful. In fact, as we shall see later, revision is needed only if a preliminary available mental model is not sufficient enough to make sense of something, and/or shows inconsistency with one’s total configuration of experiences that are relevant in the context of the particular situation. Due to the uniqueness of mental models, the participants’ respective interpretation of the same discourse is necessarily different (Van Dijk 2018).

The main two types of mental models that SCA defines are situation models and context models. Situation models or semantic models represent the individuals’ subjective understanding of the situation, or their take on the subject matter, i.e. what the discourse is about, or the experience aims at. Semantic models are the cognitive correlates of the “intentional” and “referential” function of language. Context models or pragmatic models account for how individuals define the circumstances of an experience or the communicative situation in which they are involved in terms of relevance. Context models represent the “socially” and “communicatively” relevant characteristics of a situation. They help to avoid ambiguity and orient participants to act and speak appropriately (i.e. accordingly) in a particular social situation. They control the content, style and genre of discourses, depending on spatio-temporal factors, the institutional environment, the identity, status and role of participants, and their relationship. For example, we explain the circumstances of the same accident to a friend in a different manner than to the police (Van Dijk 2014b, 2015b, 2018).

Although uniquely constructed, mental models are based on, and “instantiated” from, the socially shared generic knowledge of the participants which manifests in language. Thus, language is indicative of, and makes the subjective interpretations of participants mutually accessible. Essentially this is why individuals, using the same language, can understand each other in a conversation (Van Dijk 2014a, 2018, pp. 49–61, 2012a, 2014b).

Van Dijk has criticised cognitive- and social psychology for neglecting the socially shared nature of knowledge and the knowledge-based interaction between members of epistemic communities respectively. He claims that paying more attention to these issues, and an analysis of how mental models function, i.e. the processes underlying discourse production and comprehension, would be instrumental in bridging the “notorious micro-macro gap” in social sciences (Van Dijk 2012a, 2014a, pp. 12–13). I will demonstrate that phenomenological sociology could step up as a resourceful ally to SCA in this regard, as their fields of interests intersect significantly. The article will go on to introduce Schutz’s insight into the (in) accessibility of others’ intentions, and, drawing on his analysis of intersubjective understanding, it will address the process that controls discourse production and interpretation, and the function of language. The second part of the article will discuss some of SCA’s key concepts, such as personal- and socially shared knowledge, and legitimation from a phenomenological sociological perspective.

2.2 Alfred Schutz

Schutz was interested in the role of subjectivity in the construction of social reality, and, conversely, how individuals’ understandings and actions are influenced by socially pre-established structures (Schutz 1970, pp. 25, 79–122; cf. Zahavi 2019, pp. 106–107; Overgaard and Zahavi 2009). Schutz argued that the social world is constituted and manifests in the first-person perspective; it appears intelligibly only through subjective interpretations, in the subjective meaning-context of lived experiences. Thus, according to Schutz, in order to understand how society functions, social sciences should focus on the individual to whom it meaningfully exists (Schutz 1972, pp. 74–86, 139–144; Schutz and Luckmann 1974, pp. 15–18).

Schutz’s point of departure was his criticism of Max Weber’s social action theory. Weber recognised the fundamental role of subjectivity in the constitution of social reality: the meaning of social relations and structures is derivative of, and reducible to, as Weber calls it, the “intended meaning” individuals “attach” to their own acts. Thus, Weber argued that sociologists can only understand and describe the former through the interpretation of the latter. While Schutz agreed with the key tenet of Weber’s framework, he problematised that the “intended”, or more accurately, the subjective meaning of an action had not been addressed by Weber in its actual complexity. Weber did not differentiate between the meaning of our own acts and that of others. Nor did he explain how these meanings are constituted, established and interpreted, and the different forms in which the other self is given to the self; i.e. how we come to understand others in the first place. Schutz points out that Weber’s failure to adequately conceptualise these issues has led to inconsistencies and contradictions in his theory. As he argued, it is only through a systematic analysis of the concept of meaning and the process of meaning-constitution that we can understand “the intended meaning” of an action, hence the meaning-structure of the social world (Schutz 1972, pp. 1–20).

2.2.1 Meaning-constitution and the subjectively meaningful action

To explicate meaning Schutz adopts and combines Husserl’s concept of meaning-endowment and Bergson’s concept of inner duration (Schutz 1972, pp. 45–57). For our purpose it suffices to establish that, for Schutz, meaning is the “reflective Act of attention” which “singles out” an experience from the otherwise unnoticed flow of experiences (Ibid, pp. 51, 65, 71). Thus turning attention to and distinguishing an experience within the stream of consciousness, it becomes “constituted” or “discrete”. What is decisive, as Schutz notes, is that only a past experience can be meaningful: “for meaning is merely an operation of intentionality, which, however, only becomes visible to the reflective glance” (Ibid, p.52). Instead of being an intrinsic feature of the experience itself, meaning is the way in which one turns towards one’s own elapsed experiences. Thus, the reflective attention presupposes a particular attitude on the part of the self (Ibid, pp. 42, 69).

Schutz, drawing on Husserl, defines behaviour as a “meaning endowing conscious experience” or an “attitudinal Act”. Behaviour is a discrete unity of experiences resulting from a spontaneous activity. It is distinguished from other experiences by virtue of the particular attitude one takes up when reflecting on that activity. Because activity is a process, a series of experiences, the self can only reflect on it from a “vantage point” by means of “retentions” (like a freeze-frame) or “recollections”. One may recollect a behaviour from memory by a unified “single grasp” (“monothetically”) or phase-by-phase reconstructing the original structure of the experience (“polythetically”) (Schutz 2011, pp. 137–142; 1982, pp. 46–47; 1972, pp. 53–57, 71; Schutz and Luckmann 1974, pp. 53–56).

Actions, as opposed to behaviours, do not only consist of an attitude but also a “project”; actions are future-oriented in the form of a plan or a goal in order to solve a problem. This anticipatory character of an action is only seemingly inconsistent with the retrospective nature of reflection. Reflection, besides retentions and recollections, functions by means of “protentions”. In protentions, the self reflects on the action as something that will have been done as a completed unit, i.e. in the future perfect tense. The meaning of an action is “its corresponding projected act”. The scope or breadth of reflection (i.e. the project) is crucial concerning the meaning of an action. Schutz emphasizes that the act as a unit is divisible into potentially infinite subacts, and each can be regarded as a unit itself. For an external observer, it is impossible to identify the actual phase that is momentarily relevant for the actor within the overall spectrum. Observing a woodcutter chopping logs with an axe, one might come to the conclusion he is chopping logs with an axe, while the woodcutter himself is actually working to get paid, so that he can get a chainsaw, work more, start his own logging company, and so on; perhaps he is not even a woodcutter, just a man working out. It follows that meanings cannot be arbitrarily “attached” to actions as they are meaningless without the anticipated project (Schutz 1972, pp. 24–31, 57–71).

2.2.2 Specific meaning and the relevance of relevance

As already implied, the specific meaning of an action may vary and depends on the particular mode of attention and its “modifications” and the corresponding attitude one takes up at the particular moment of reflection. The perspective of attention and the degree of scrutiny is determined by my particular pragmatic interest in the particular situation (Schutz 1972, pp. 71–96). This already explains Van Dijk’s car-driving example; the role of interest in meaning-constitution needs further clarification nonetheless.

An experience is always constituted in the context of past constituted experiences. That is, the meaning of an experience is always determined in the configuration of previous lived experiences that are synthesized in the stock of knowledge as meaning-contexts. To identify an object as a car, I refer back to the configuration of my previous experiences of cars. Meaning-contexts conceptually encompasses and defines the “essence” of an experience and are called interpretive schemes or types. The structure of the stock of knowledge will be explained in more detail later. What is important here, as Schutz points out, is that the specific meaning of a new experience is essentially constituted by a “passive synthesis of recognition”, i.e. the reflective glance of the ego to its own stock of knowledge. Synthetic recognition is the classification or “self-explication” of the lived experience, whereby experiences are compared to schemes for a match; interpretation is thus “the referral of the unknown to the known” (Schutz 2011, p. 105; 1972, pp. 83–84). The stock of knowledge comprises all the possible schemes (and the corresponding attitudes) ever applied in previous situations involving a car: driving home from IKEA - means of transport; changing the oil - machine; being hit while cycling - hazard, and so on. Each of these schemes has interpretative relevance as far as cars are concerned; i.e. they all are on the horizon or the interpretive spectrum of the experiential object which features the basic characteristics typical to a car. To decide which one of them defines a particular situation depends on my prevailing interest. As earlier discussed, the meaning of an action is the projected act, i.e. the goal or “in-order-to motive” of the action. Schutz thus refers to the meaning context which determines the meaning of the action as “motivational context”. In other words, the specific meaning of an action is constituted in the motivationally relevant meaning-context of past experiences that corresponds with the projected act. Motivational relevance also consists of a “because-of motive” which in hindsight explains and determines the projected act based on previous experiences; i.e. why the problem is important in the first place. I use my car in order to get a cupboard home from IKEA, because cupboards are heavy and cars are handy to carry heavy things. This system of motivational relevance that guide us to master a situation and solve a problem called interest (Schutz 1966, p. 123; Schutz 1972, pp. 74–96; 2011, p. 129).

If an experience does not, or not sufficiently, fit an interpretive scheme in the stock of knowledge, it becomes problematic or thematically relevant. Thematic- or topical relevance accounts for, inter alia, singling out an experience from the flow of experiences, as something unfamiliar that catches our attention (Schutz and Luckmann 1974, pp. 186–189). Schutz differentiates between imposed- and intrinsic topical relevance. In the former case, experiences become thematic for a reason out of our control, in the latter, we make an experience thematic voluntarily. Each form of thematic relevance has its own sub-categories. A specific category of intrinsic relevance is when we “enlarge or deepen” the prevailing theme and customize interpretive schemes accordingly. When purchasing a car, we are never looking for just a car, but are also interested in the make and model of the car, its body style, fuel consumption, storage capacity and so on, depending on our purpose of use. The car as the “paramount theme” remains the same, the possibilities for “sub-thematization” within the spectrum of its inner horizon, i.e. for classifying its intrinsic content, are virtually infinite. This explains how interest controls the degree of scrutiny and hence determines the constitution of meaning as mentioned earlier (Schutz 2011, pp. 107–112; Schutz 1971 pp. 120–134; 1966, pp. 116–132).

Thematic-, motivational- and interpretative relevance are interconnected together, and with interpretive schemes and types stored in the stock (Schutz 2011, pp. 123–150; 1972, p. 193; 1962, pp. 283–286; Schutz and Luckmann 1974, pp. 182–229). What is problematic for me, why I become interested in, and how I manage to get a grasp of certain problems, all depend on my past experiences (and the lack of them), i.e. my current stock of knowledge. Conversely, it follows that the learning process, hence the “chronological” or “autobiographical” structure of my knowledge is a function of my jointly sedimented relevance. Relevance are thus of great importance in Schutz’s theoretical framework (cf. Dreher 2011; Nasu 2008). It is the interrelated structures of relevance that accounts for the habitual and stereotypical knowledge we rely on to navigate in everyday (communicative) situations and, ultimately, in the social world; and as such, explains the function of SCA’s context models.

2.2.3 Intersubjective understanding

As Schutz maintains, due to the highly complex and necessarily subjective nature of meaning-constitution (retentions, polythetic acts of recollections, protentions, and so on), the intended meaning of an individual is inaccessible to others in the exact form in which it is constituted within one’s stream of consciousness. Individuals’ self-explication of their own lived experience and its interpretation by an observer always occur in totally different meaning-contexts. Moreover, as an observer, I cannot be certain whether one in fact reflects upon one’s own lived experience in the sense necessary to constitute an action as defined earlier, and how (i.e. in what exact meaning-context). Observable bodily movements, expressions are merely the “indications” of one’s subjective meaning. According to Schutz, it is nonetheless possible to understand others’ subjective meaning, their motives, whys and purposes and get an insight into one’s own meaning contexts. However, it is only partly achievable and is always approximate, and observers must rely on the interpretation of their own lived experiences (Schutz 1972, pp. 97–115).

Schutz distinguishes between “expressive movements” and “expressive acts”. While the former are meaningful only for the observer, the latter have a communicative purpose. Expressive acts are communicative acts whose in-order-to motive is to inform, or more precisely, to be interpreted. Hence, expressive acts use objectified sign-systems such as language. On the one hand, signs serve as interpretive schemes for the lived experiences which they designate. On the other hand, through their “expressive function”, signs indicate or “appresent” the subjective meaning of sign users. To understand each other in communication, the interpretive- and expressive schemes of the participants must match. However, even if we speak the same language, these frames never fully overlap due to the differences in the biographical situation of the participants. As Schutz underlines, whenever we use or interpret a word, its actual meaning always points back to the unique circumstances of the situation in which we learned to use it, or in which we have since been using it. That is, words, besides their objective meaning (dictionary entry)Footnote 1 also have a subjective component. To genuinely understand one another, interpreters must try to detect the particular subjective experience of the speakers in the situation when speakers link the sign and the signified; i.e. when they “establish” the meaning of the sign (Schutz 1972, pp. 116–125; 1970, pp. 202–207; 1962, pp. 294–315; Schutz and Luckmann 1989, pp. 148–153). Not only that, the meaning of a word is also “occasional” and is determined by the overall discursive context. As Schutz maintains: “discourse is a sign-using act” (Schutz 1972, p. 125). That is, the meaning of a word gradually develops over the span of the project in which it is embedded, i.e. in the meaning-context of the sentence, the paragraph, and so on. As long as the discourse as a unit is not completed, the interpreter may only have a provisional understanding of its meaning.

As Schutz points out, when interpreting someone, we always try to put ourselves into the shoes of the speaker to imagine why they formulate their thoughts as they do. Conversely, as speakers we try to select our words so that the interpreter can easily understand our point, attitudes, feelings, based on our past experiences of interpreting others. In both cases, the participants try to replicate each other’s interpretive and expressive scheme respectively, and in doing so they draw on their knowledge of one another (identity, speaking habits, interpretation skills, knowledge). Although this knowledge evolves in the communicative situation, the “imaginative reconstruction” of the speaker’s project can never be fully achieved by the interpreter, nor can the speaker be certain whether they are fully understood. It nonetheless follows that the “degree of anonymity” or “intimacy” of communication between participants significantly affects the understanding of one’s intended or subjective meaning (Schutz 1972, pp. 126–138).

Schutz calls the basic form of attention by which we turn towards others’ stream of consciousness Other-orientation. Every social interaction is a reciprocal Other-orientation when the participants’ motive to be understood mutually and dynamically affects communication; the in-order-to motive of my question becomes the because-of motive of your answer. Social interaction is thus “an intersubjective motivational context” (Schutz 1972, pp. 146–159). When the other is physically present, we talk about Thou-orientation. The archetype of all forms of social relationship is a reciprocal Thou-orientation, i.e. the face-to-face, direct relationship, where our streams of consciousness are interlocked, and we are “growing older together” in a We-relationship (Schutz 1972, pp. 103, 163–164; 1962, pp. 218–222). As Schutz points out, it is only the We-relationship where we have the chance to live through one’s action up to the fulfillment of the projected act. Because we share the same environment in living through our experiences as one single flow, we are in a position to synchronise our expressive- and interpretive schemes; we may as well ask each other questions if we are unsure about our interpretation. In each moment of the face-to-face encounter our knowledge of each other is being revised and updated (Ibid, pp. 159–172; cf. Zahavi 2014, pp. 141–144).

Schutz refers to the participants of a We-relationship as each other’s associates or consociates. Besides our associates, we have social relationships with our contemporaries, predecessors and successors (Schutz 1972, pp. 8, 109, 142–143). Although different in character, each of these relationships is derivative of the We-relationship. How we understand social structures is virtually equivalent with the way in which we understand our contemporaries, those with whom we coexist in time but are not in a face-to-face relationship. Schutz calls this specific form of Other-orientation They-orientation. The world of contemporaries spans a wide spectrum of anonymity: a friend with whom I had lunch yesterday; a group of individuals whom I do not know by name only identify by function, such as postmen; collective entities, such as nations or states; or the unknown maker of the vase standing in my living room (Ibid, pp. 180–183). As Schutz points out, since we have no direct access to the flow of experiences of our contemporaries, to understand them, we can solely rely on our own abstract, synthesized experiences of the social world in general; the typical characteristics of people we have encountered. That is, we understand contemporaries by means of interpretive schemes called personal ideal types. Schutz differentiates between characterological types and habitual types. The former encompasses the typical characteristics of persons who behave or act in a certain way, the latter refers to functions and roles, such as the postman. As Schutz notes, although ideal types that define social collectivities are characterised by a much higher degree of anonymity, are merely an “abbreviation” for the complex network of personal ideal types of their members (Schutz 1972, p. 184, 196–199; cf. Zahavi 2014, p. 145).

What is important is that ideal types become integrated parts of the stock of knowledge, and we draw on them not only in They-relations, but also in face-to-face interactions (Schutz 1972, pp. 185–186). Whenever we step in a We-relationship, we always take up a specific preliminary attitude and presuppose a set of because- and in-order-to motives relevant in the situation determined by ideal types (Schutz 1972, pp. 171–172). The difference between face-to-face and indirect interactions is rather “gradual” than “categorical” if not insignificant (Knoblauch 2013). As Zahavi comments, the understanding of others in everyday life never takes place in a “vacuum” (Zahavi 2014, p. 146). It is precisely our integrated network of ideal types as meaning contexts that control the communicative situation, and automatically adjust a corresponding attitude depending on whether we are interacting with our friend or the police. Thus, the function of Schutz’s ideal types are nothing less than that of SCA’s context models.

2.2.4 Types

Not only our contemporaries and associates but virtually everything we encounter in both the physical and social world is interpreted in terms of types; no experience is “pretypical” (Schutz 2011, p. 125; 1962, pp. 281–282; Schutz and Luckmann 1974, p. 232). To a certain extent, every experience seems familiar from the outset, because we can typify them based on our previous experiences: “What is newly experienced, is already known in the sense that it recalls similar or equal things formerly perceived” (Schutz 1970, p. 116). Whenever we see a dog, even if we cannot tell what breed at first sight, we know it is a dog. Types are “taken for granted” on the common-sense level, and mainly derive from our socio-cultural heritage passed on from generation to generation. Types are acquired not only through socialisation and education nonetheless, but also develop by the explication and sedimentation of our own experiences. The matrix of typified experiences constitutes our primary source of knowledge, or the subjective stock of knowledge as mentioned earlier. The stock of knowledge is our interpretative toolkit, but also serves as guidance for us to act in an appropriate, typical way in a particular, typical situation. Schutz bases this compass function of the stock of knowledge on the correlative assumptions that Husserl calls “and so forth” and “I-can-do-it-again”. Simply put, the former means that the validity and meaning of our experiences is relatively constant over time, and the latter refers to our ability to replicate previously successful actions to achieve a designated aim in a similar situation (Schutz 2011, pp. 125–128; Schutz and Luckmann 1974, pp. 7, 238–241).

Types are not monoliths but are modified and replaced if necessary. Types are only taken for granted “until further notice”, i.e. until contradiction or until a circumstance motivates us to revise our assumptions (Schutz 1970, pp. 74–76, 116–122; 1972, pp. 181–201). As already mentioned, types and schemes are correlated and merged with relevance, and always point to a problem and the underlying interest. That is, types are taken for granted as long as they solve a problem, i.e. they sufficiently determine the object of my experience as something I already know and familiar with, and no further investigation is necessary for my actual purpose. If I encounter an atypical or unfamiliar object which does not sufficiently fit the type, i.e. the experience is “novel”, the validity of the type becomes questionable. Based on the overall characteristics of the object determined by a deeper scrutiny, I then have to narrow down, expand or entirely replace the type. However, everything has its horizon of “determinable indeterminacy” and a change of purpose itself may convert taken for granted things into something problematic. Familiarity with the typical aspects of mushrooms which distinguish them from animals and plants is not sufficient enough to decide whether they are edible or poisonous. That is, it cannot be taken for granted that a particular mushroom is edible just because it is 100 % a mushroom. Only after further investigation and the establishment of subcategories I can pick mushrooms that look like, e.g. a Champignon assuming they are harmless, but only until further notice (Schutz 2011, pp. 125–129; Schutz and Luckmann 1974, pp. 8–15).

3 Knowledge and society

3.1 Personal knowledge - subjective stock of knowledge

The preliminary categories of knowledge that SCA operationalises are social knowledge and personal knowledge. The latter is defined as the “justified beliefs of individual members acquired by applying the epistemic criteria of their community to their personal experiences and inferences” (Van Dijk 2014a, p. 21). Personal knowledge acquisition, i.e. the construction of mental models, is predominantly done against the background of socially shared knowledge, but mental models evolve as they are reappropriated and updated in line with individuals’ new experiences and interactions with others (Van Dijk 2014a, pp. 47–89; 2015a, b, p. 67; 2018, pp. 56–110).

In terms of phenomenological sociology, knowledge acquisition is the sedimentation of already constituted experiences in the subjective stock of knowledge, the matrix of schemes, relevance and types. The totality of SCA’s mental models (situation- and context-models) is nothing less than this subjective stock of knowledge that helps us to determine “here and now” experiences. As already implied, each previously sedimented experience in the subjective stock of knowledge relates to our “pragmatic” or “plan-determined” interest in a particular type of situation. In other words, the typicality of experiences, hence that of the situation in which they occur, is conditioned by relevance (Schutz and Luckmann 1974, pp. 182–243; Schutz 1962, p. 134). Because we encounter the world in situations, i.e. experiences always occur in situations, and each situation is “defined and mastered” based on the stock of knowledge, Schutz and Luckmann call this relation as the “situation-relatedness” of the stock of knowledge.

Schutz and Luckmann note that both the situation and the subjective stock of knowledge have a historicity: the latter is the sum of all the previous experiences sedimented in it; the former is always recognised and understood as a result of prior situations. More significantly, situations and experiences are sequentially defined over the life span of each individual, i.e. they are “biographically articulated”. As discussed earlier, the meaning of an experience is the aggregate function of all prior accumulated experiences the stock of knowledge comprises at that particular moment; the same applies to each previous element of the stock of knowledge at its respective stage of incorporation. That is, the stock of knowledge has a highly individualised, layered structure. Moreover, the intensity, the duration and the frequency of experiences vary from person to person. Thus, as Schutz and Luckmann point out, although experiences are sedimented in an “idealised” and “verbally objectivated” form, the stock always has a unique, private and constantly evolving character (Schutz and Luckmann 1974, pp. 52–58, 99–122; Schutz 1972, pp. 74–78; 1962, pp. 9–10).

However, only a small part of the subjective stock of knowledge is construed by the “independent” and situational interpretative process described above; mental models are derived primarily from socially shared knowledge. First of all, the relevance-system that underlies the individual sedimentation process is socially conditioned. As Schutz notes, it is because the private interest of the individual always relates to the interests of others; the situation in which it occurs, no matter how it is defined by the individual, is always a social situation (Schutz 1970, p. 121). For Schutz, intersubjectivity is a “fundamental ontological category of human existence”, a precondition of all our immediate experiences (Schutz 1970, p. 31). The vast majority of the subjective stock of knowledge derives from the socially objectivated experiences of others, i.e. the social stock of knowledge. Again, it must be stressed that due to the subjective biographical incorporation, it necessarily undergoes certain reconfiguration in line with the individual’s prevailing meaning-contexts. In other words, and in terms of SCA, mental models, although “abstracted” from shared, general knowledge, but at the same time are always personal and unique (Van Dijk 2014a, p. 51).

3.1.1 Internalisation

The socially derived facet of the subjective stock of knowledge is essentially developed by the learning process of internalisation (Schutz and Luckmann 1974, pp. 243–261, 312). Taking Schutz’s work as a point of departure, Berger and Luckmann have developed a comprehensive framework of the social construction of knowledge; how it is externalised, objectified and internalised (Berger and Luckmann 1967; Berger 1969, p. 4). They extensively analysed the correlative relationship between objective- and subjective reality, i.e. between the taken-for-granted, common-sense world and its subjectively meaningful representation by the individual. They argued that the construction of subjective reality, or knowledge acquisition, is done by the internalisation of institutions, i.e. objectified and habitualised practices and behaviour patterns that we learn during our socialisation (Schutz and Luckmann 1974, pp. 247–261; Berger and Luckmann 1967, pp. 70–109). The authors assign a crucial role to significant others who are “in charge” of our socialisation (Ibid., pp. 151–152). Significant others are our first point of contact to the world, who “mediate” the world to us. Their understanding and definitions of things, situations are taken for granted by us. Not only do we interpret things and assign a meaning to them as passed on by significant others, but we only get familiar with those things that our significant others find important to get familiar with. In other words, we learn about the world selectively and through a filter determined by our respective significant others’ position in the social structure, their education, religion, taste, location, age, political preferences, and so on. Berger and Luckmann note that our primary socialisation is not only a cognitive learning process but is also “emotionally charged”. As a child, we identify with our significant others, our parents in particular. Through internalisation, we make their attitudes, language, roles our own by subjectively appropriating them. In that way identifying with our significant others we acquire our identity of our own; i.e. our primary self is reflective. Since identity consists of one’s understanding of, and attitude to, the world, through the appropriation of their identity we simultaneously internalise their world. “Subjective appropriation of identity and subjective appropriation of the social world are merely different aspects of the same process of internalisation” (Ibid., p. 152). Once these internalised behaviour patterns, views, beliefs, emotions and attitudes to worldly objects and situations are mutually confirmed by our peers other than significant others, they become generalised. Thus, the individual comes to identify with the society and becomes its member; the individual internalises the objective-, common-sense reality. “Society, identity and reality are subjectively crystallised in the same process of internalisation” (Ibid., p. 153). By the abstraction of internalised institutions on a general level, we establish a bridge between subjective and objective reality. Although there is a constant communication and balancing between the two, we never really internalise, or even are aware of, the latter in its entirety. It is simply because a) what is passed on to us in the process of socialisation is determined by the spatially and temporally (historically) fragmented social distribution of knowledge, as well as its role-specific heterogeneity; and b) because knowledge acquisition is “biographically” determined; it is both unique and finite (Ibid., p. 154; Schutz and Luckmann 1974, pp. 256–261, 291–318).

What is decisive is that our understanding of the world, including ourselves, is in constant dialectical relationship with the society: on the one hand, identity is shaped by social relations, processes and situations, and identity impacts upon these social structures by maintaining, modifying or reshaping them: “societies have histories in the course of which specific identities emerge; these histories are, however, made by men with specific identities” (Berger and Luckmann 1967, p. 194).

3.2 Social knowledge - social stock of knowledge

Social knowledge or social beliefs are defined by SCA as “the shared beliefs of an epistemic community, justified by contextually, historically and culturally variable (epistemic) criteria of reliability” (Van Dijk 2014a, p. 21). General, or socioculturally shared knowledge is the category of social beliefs that is generally accepted in society at large, while e.g. ideologies and prejudices are only shared by specific social groups. Social knowledge is socially acquired, shared and communicated, and always relates to socially relevant issues (Van Dijk 2014a, pp. 85–138).

As mentioned in the previous section, socially shared knowledge is the primary source of our mental models. What still has not been discussed is how the social stock of knowledge itself is constructed. As Schutz and Luckmann point out, although subjective acquisition of knowledge would be theoretically possible without the social stock of knowledge, developing the latter without the former is manifestly absurd. The fundamental origin of the socially shared knowledge is personal knowledge, and the transference of the latter into the former is done by its objectivation (Schutz and Luckmann 1974, pp. 262–265). With Van Dijk’s words: “we use mental models to construe generic knowledge by abstraction and generalization” (Van Dijk 2014a, p. 85).

The basic level of objectivation is when a subjectively acquired knowledge that solves a problem is “imitated” by others, whereby it becomes a taken-for-granted “recipe” knowledge or skill of the entire community. However, this “pre-symbolic” form of objectivation is still physically bound to the situation in which the original subjective experience occurred. As already implied earlier, it is only an objectivation done by a mutually shared system of signs, i.e. by language, that can “anonymise” and “idealise” the experience and make it meaningfully transferable regardless of the original spatial, temporal and biographical attributes of the experience (Schutz and Luckmann 1974, pp. 261–286). Although objectivation is a necessary, but not sufficient condition for subjective knowledge to be incorporated into the social stock of knowledge; it must also be socially relevant, a solution to a typical problem. In other words, the social stock of knowledge is a depository of solutions to everyday, “typically similar problems” of the community (Ibid., pp. 287–291). More significantly, this “accumulation” of the social stock of knowledge is a historical process that varies between societies, hence the stratification of the stock of knowledge is never uniform. It is always determined by the prevailing social structure and, from the ground up, by the first-order objectivations as the fundamental worldview of the community (Ibid., pp. 295–299, 305–308). Thus, language always reflects and transmits a particular historically and socially pre-constructed reality (Schutz and Luckmann 1989, pp. 148–157). In other words, the social world presents itself from a perspective which always mirrors the particular linguistic and cultural settings of a given society at a particular time. This is precisely because language reflects the relevance structure prevailing in a certain historical community that found an experience significant and relevant enough to assign a separate term for it (Schutz 1970, p. 96). Language objectifies and typifies experiences and situations, and simultaneously incorporates them into the social stock of knowledge, thus making them available for all members of the collectivity to describe similar experiences. Because this sedimentation of knowledge has a spatial and temporal arrangement, language becomes the “depository” of intersubjectively objectified experiences of a particular community in a given historical period (Berger and Luckmann 1967, pp. 53–56, 85–89; Schutz 1970, pp. 96–98; Schutz and Luckmann 1974, pp. 233–235, 247–251).

3.2.1 Epistemic communities and the social distribution of knowledge

Epistemic communities are “collectivities of social actors sharing the same knowledge” (Van Dijk 2014a, p. 147). Membership in epistemic communities always presupposes a shared knowledge being in place to behave, act and interact appropriately within the community and collectively towards shared goals and objectives (Van Dijk 2014a, pp. 139–154). Shared knowledge may vary between epistemic communities; what is taken-for-granted in one, it might be considered false in another (Van Dijk 2012b).

Generally relevant knowledge is the category of the social stock of knowledge that relates to problems that concern everyone in the community; e.g. we all lock the door when leaving home (and wash our hands upon return for that matter). However, the system of problems, i.e. the relevance structure of a society is not homogeneous. The social stock of knowledge relieves individuals from developing solutions to familiar recurring issues, thus they are able to turn towards new and more complex ones. Certain problems become relevant and shared only by specific groups of the society, and the related knowledge is, accordingly, passed on within these groups only. In other words, certain layers of the social stock of knowledge are clustered and bound to roles (Schutz and Luckmann 1974, pp. 291–295). Formally put, performing a role means performing certain socially objectified and typified actions that occur in the meaning context of a particular cluster of the social stock of knowledge shared by a collectivity of actors of the same type. This is why Berger and Luckmann note that objective reality, i.e. the social world, manifests by means of roles (Berger and Luckmann 1967, pp. 89–96). While generally shared knowledge remains accessible to everyone, role-specific knowledge becomes structurally differentiated and relatively isolated as a result of the historical accumulation process within the respective epistemic group. Moreover, the “relief” of out-group members to be able to turn to “specialists” whenever a problem occurs outside the province of the generally shared knowledge results in the institutionalisation of role-specific knowledge. Essentially this process accounts for the division of labour in a society, as well as for the “inequalities” in the social distribution of knowledge (Schutz and Luckmann 1974, pp. 299–316). The more autonomous and inaccessible the special knowledge becomes, the more chances there are for power struggles for dominance being involved in its distribution: “group of experts form one of the institutional catalysts of power concentration” (Ibid., p. 315).

As a result of the historical accumulation, the distribution of special- and general knowledge within the social stock of knowledge is never constant. The latter can develop into the former and vice versa, promoted or restricted under the control of certain interest groups. As has been mentioned, due to the complexity of the social structure, different “versions” of the general knowledge necessarily develop. Not only that, certain versions of the shared knowledge might become the “special property” of certain social groups and live on in the form of ideologies. The subjective acquisition of knowledge is never definitively complete. New problems occur, and things may reveal new aspects when looked at from different perspectives whenever we interact with members of other epistemic communities (Ibid., pp. 312–321, 326–327; cf. Van Dijk 2015a, b, p. 71).

3.3 Legitimation

SCA assigns a crucial role to legitimation in knowledge acquisition. Ideologies, certain attitudes and opinions are only shared by specific groups in the community. In order to be accepted by others, they have to be appropriately tailored and presented in a way in which the target audience can easily identify with the purpose of the speaker (Van Dijk 2014a, p. 92). Successful transmission of such knowledge depends not only on the reliability of the source, but a Common Ground must be established between the speaker and receiver in the particular communicative situation. Depending on the relevance structures and interests of the audience, asylum seekers, for example, can be portrayed both as people fleeing war zones, or as a burden to the welfare system. In short, knowledge is considered legitimate by the receiver, if and only if integrative and well-formatted with reference to the shared beliefs, common-sense knowledge, problems, attitudes and (discursive) practices of the particular social group the receiver belongs to (Van Dijk 2014a, pp. 153–155, 117–120, 222–309). Legitimation is essentially the explanation, justification and rationalization of claims and actions of the speaker indicating that they fall within the existing legal-, political-, moral-, i.e. the overall social order of the community (Van Dijk 1998, pp. 255–262).

Berger and Luckmann define legitimation as the “second-order objectivation of meaning” to facilitate the cognitive and normative integration of first-order objectivations that are already institutionalised. The purpose of legitimation is to preserve the plausibility of the institutional order as a whole and make it subjectively meaningful and objectively available for the (second generation) members of the community (Berger and Luckmann 1967, pp. 110–146). Legitimation explains and justifies the institutional order by “ascribing cognitive validity to its objectified meanings” and “giving a normative dignity to its practical imperatives”; stories, proverbs and theories are instrumental for that purpose (Ibid., pp. 111–113). Not only that, the acceptance of a newly introduced institution depends on whether it is recognised as a “permanent” solution to a “permanent” problem of the community (Ibid., 1967, p. 87).

Berger and Luckmann note if institutions are to be taken for granted, they have to be justified not only in practical terms, but also by embedding them into a symbolic universe (Ibid., pp. 110–134). As a result of symbolic legitimation, practices and activities prescribed by institutions become uplifted as a mode of participation in a symbolic universe thus transcending their everydayness. Symbolically legitimised knowledge might persist even if they lose functionality or relevance; not because they would be necessary or “work” but because they are “right” and pivotal to preserve the tradition (Ibid., p. 135; Schutz and Luckmann 1974, p. 298). Taking the example of the police as an epistemic community, e.g. the controversial stop and search practices can be portrayed by the legitimator not only as necessary to chase criminals, but simultaneously as something the “watchers” or “guardians of people” would do in order to serve the public, to protect the citizenry and to enforce the law. Similarly to ideologies, symbolic legitimation links past, present and future by prompting the collective memory, thereby creating a frame of reference within which the community functions (cf. Berger and Luckmann 1967, p. 120). Embedding, for example, a new policy proposal in the historical continuum provides a cohesive and transcendent significance for the proposal. David Cameron, then PM of the UK, praised the “legacy” of Magna Carta in his attempt to replace the Human Rights Act with a “British Bill of Rights” in order to dodge the jurisdiction of the European Court of Human Rights. He did so precisely because the problem of legitimation arises when the institutional order itself is about to change.

Van Dijk defines referential local coherence as “the relations between the facts referred to by the discourse and those represented subjectively in the situation model of the discourse” (Van Dijk 2014a, pp. 249–250). As Berger and Luckmann argue, when new institutions are to be introduced replacing or complementing old ones, the former must be in balance with the knowledge, values and beliefs related to the latter. In other words, the transmission of meanings associated with pre-existing institutions to new ones, with reference to the “salient elements” of the overall institutional order, is crucial to preserve plausibility. New institutions must be aligned with the general values of the community. For example, reforms and policy proposals affecting an epistemic community must be translated into pre-existing schemas, behaviour patterns and practices, and meet the objectives of the community. Members of a community can identify with new institutions only if both the purpose of the institution and the actions prescribed to achieve that purpose are plausible and fit well within their roles (cf. Berger and Luckmann 1967, pp. 110–122, 157–164).

3.3.1 Delegitimation and universe-maintenance

Since multiple symbolic universes exist, universe- or reality-maintenance and neutralisation of competing universes is necessary to preserve plausibility for the community. The very existence of alternative and competing universes poses threat to the claimed inevitability of a particular institutional order (Berger and Luckmann 1967, pp. 126–146, 166–182). In other words, delegitimation of rival ideologies is an important aspect of the legitimation process (Van Dijk 1998, p. 258). Neutralisation may take place by the incorporation and merge of conflicting objectives and arguments with one’s own to enrich and strengthen the latter, or by their “segregation” as deviant and only appropriate for different cultural communities (Berger and Luckmann 1967, pp. 138–140).

However, the more artificial the character of certain knowledge to be transmitted is, the more vulnerable it becomes to competing views, and as such it is prone to displacement (Berger and Luckmann 1967, p. 167). The transmitted knowledge must be in relative balance not only with pre-existing in-group knowledge, but also with that of other epistemic communities, i.e. the rest of the society. The validity of knowledge must be confirmed in social processes during interaction with others. The explicit and emotional confirmation by our significant others, but virtually everyone we encounter in everyday life, play an important role in this universe-maintenance in order to preserve the plausibility structure. If, on the one hand, such confirmation is missing, but a competing legitimating apparatus is in place that disintegrates the current system of knowledge, on the other, the rejection and transformation of identity might be a possible outcome; the authors bring religious conversion as an example (Ibid., pp. 165–182).

4 Conclusion

This article argues that phenomenological sociology remains increasingly relevant to sociological research. Phenomenology, or as Schutz (1978, p. 140) phrased it, “the treasure of knowledge opened up by Husserl” has been long neglected by contemporary social sciences. Schutz and his successors fused phenomenology with sociology and developed a comprehensive framework analysing the interrelated structures of subjectivity, knowledge and the social world. That is, phenomenological sociologists extensively analysed the subject matter of the Sociocognitive Approach in Critical Discourse Studies. Among others, the concept of scheme, type, relevance, subjective- and social stock of knowledge are highly instrumental in understanding how mental models and the socially shared knowledge are constructed and function in a communicative situation. Schutz’s theory of intersubjective understanding, the concept of signs, the interpretive- and expressive function of language and his analysis of the We-relationship provide a strong theoretical support to understand the processes that control discourse production and interpretation, and how participants can infer each other’s subjective meaning (intentions) in a communicative situation. Schutz’s analytical framework is systematic, brilliantly nuanced and detailed, therefore the scope of the article is extremely, and necessarily, limited; nor does it discuss the underlying concepts developed by Husserl. The potential of phenomenological sociology to provide a strong theoretical support for SCA has nonetheless been demonstrated and should be clear, which will hopefully draw the attention of critical discourse analysts to an unduly sidelined field.

Data Availability

N/A

Notes

I defined the objective meaning of a word as its dictionary entry for the sake of simplicity. Schutz’s concept of objective meaning is more complex than that and might occasionally be confusing when he uses objective meaning as the observer’s interpretation of the actor’s action (i.e. the observer’s self-explication of their own lived experiences) - for clarification see Yu (2010).

References

Berger, P. (1969). The sacred canopy: Elements of sociological theory of religion. New York: Anchor Books.

Berger, P., & Luckmann, T. (1967). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. London: Penguin.

Dreher, J. (2011). Alfred Schutz. In G. Ritzer (Ed.), The Wiley-Blackwell companion to major social theorists (pp. 489–510). Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

Gallagher, S. (1997). Mutual enlightenment: recent phenomenology in cognitive science. Journal of Consciousness Studies., 4(3), 195–214.

Gallagher, S. (2012). On the possibility of naturalizing phenomenology. In D. Zahavi (Ed.), Oxford handbook of contemporary phenomenology (pp. 70–93). Oxford: OUP.

Gallagher, S., & Zahavi, D. (2012). The phenomenological mind. Abingdon: Routledge.

Gurwitsch, A. (1978). Galilean physics in the light of Husserl’s phenomenology. In T. Luckmann (Ed.), Phenomenology and sociology (pp. 71–89). Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Keller, R., Hornidge, A. K., & Schünemann, W. J. (2018). The sociology of knowledge approach to discourse: Investigating the politics of knowledge and meaning-making. London: Routledge.

Knoblauch, H. (2013). Alfred Schutz’ theory of communicative action. Human Studies, 36(3), 323–337.

Nasu, H. (2008). A continuing dialogue with Alfred Schutz. Human Studies, 31, 87–105.

Natanson, M. (1973). Phenomenology and the social sciences. In M. Natanson (Ed.), Phenomenology and the social sciences, Vol 1 (pp. 3–44). Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Overgaard, S., & Zahavi, D. (2009). Phenomenological sociology - the subjectivity of everyday life. In M. Hviid Jacobsen (Ed.), Encountering the everyday: An introduction to the sociologies of the unnoticed (pp. 93–115). Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Schutz, A. (1962). In M. Natanson (Ed.), The problem of social reality: Collected papers I. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Schutz, A. (1966). In I. Schutz (Ed.), Collected papers III. Studies in phenomenological philosophy. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Schutz, A. (1970). In H. R. Wagner (Ed.), On phenomenology and social relations. Chicago: CUP.

Schutz, A. (1971). In A. Brodersen (Ed.), Collected papers II. Studies in social theory. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Schutz, A. (1972) [1932]. The phenomenology of the social world. London: Heinemann Educational Books.

Schutz, A. (1978). Phenomenology and the social sciences. In T. Luckmann (Ed.), Phenomenology and sociology (pp. 119–141). Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Schutz, A. (1982). Life forms and meaning structure. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Schutz, A. (2011). In L. Embree (Ed.), Collected papers V. Phenomenology and the social sciences. London: Springer.

Schutz, A., & Luckmann, T. (1974). The structure of the life-world: Vol 1. London: Heinemann.

Schutz, A., & Luckmann, T. (1989). The structure of the life-world: Vol 2. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Van Dijk, T. A. (1998). Ideology: A multidisciplinary approach. London: Sage.

Van Dijk, T. A. (2008). Discourse and context: A Sociocognitive approach. Cambridge: CUP.

Van Dijk, T. A. (2011). Principles of critical discourse analysis. In M. Wetherell, S. Taylor, & S. J. Yates (Eds.), Discourse theory and practice: A reader (pp. 300–317). London: Sage.

Van Dijk, T. A. (2012a). A note on epistemics and discourse analysis. British Journal of Social Psychology, 51, 478–485.

Van Dijk, T. A. (2012b). Discourse and knowledge. In J. Gee (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of discourse analysis (pp. 587–603). Abingdon: Routledge.

Van Dijk, T. A. (2014a). Discourse and knowledge: A Sociocognitive approach. Cambridge: CUP.

Van Dijk, T. A. (2014b). Discourse-cognition-society: Current state and prospects of the socio-cognitive approach to discourse. In C. Hart & P. Cap (Eds.), Contemporary critical discourse studies (pp. 121–146). London: Bloomsbury.

Van Dijk, T. A. (2015a). Critical discourse studies: A Sociocognitive approach. In R. Wodak & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods of critical discourse studies (pp. 62–85). London: Sage.

Van Dijk, T. A. (2015b). Context. In K. Tracey, C. Ilie, & T. Sandel (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of language and social interaction (pp. 198–213). Boston: Wiley.

Van Dijk, T. A. (2018). Sociocognitive Discourse Studies. In J. Richardson & J. Flowerdew (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of critical discourse studies (pp. 26–43). Abingdon: Routledge.

Wodak, R., & Meyer, M. (2015). Critical discourse studies: History, agenda, theory and methodology. In R. Wodak & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods of critical discourse studies (pp. 1–22). London: Sage.

Yu, C. C. (2010). Objective meaning and subjective meaning: A clarification of Schutz’s point of view. In T. Nenon & P. Blosser (Eds.), Advancing phenomenology: Essays in honor of Lester Embree (pp. 403–411). London: Springer.

Zahavi, D. (2004). Phenomenology and the project of naturalization. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences., 3, 331–347.

Zahavi, D. (2014). Self & other: Exploring subjectivity, empathy, and shame. Oxford: OUP.

Zahavi, D. (2019). Phenomenology: The basics. Abingdon: Routledge.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the anonymous reviewers for their useful input to this article.

Funding

The author receives funding from European Commission funded Horizon 2020 project RESPOND: Multilevel Governance of Mass Migration in Europe and Beyond (2017–2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N/A

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest/competing interests

N/A

Code availability

N/A

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gyollai, D. The sociocognitive approach in critical discourse studies and the phenomenological sociology of knowledge: intersections. Phenom Cogn Sci 21, 539–558 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-020-09704-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-020-09704-z