Abstract

Background Although clinical pharmacy is a crucial part of hospital pharmacist’s day-to-day activity, its performance is not usually subject to a holistic assessment. Objective To define a set of relevant and measurable clinical pharmacy and support activities key performance indicators (cpKPI and saKPI, respectively). Setting Portuguese Hospital Pharmacies. Method After a comprehensive literature review focusing on the metrics already in use in other countries, several meetings with directors of hospital pharmacies were conducted to obtain their perspectives on hospital pharmacy practices and existing metrics. Finally, five rounds with a panel of 8 experts were performed to define the final set of KPIs, where experts were asked to score each indicator’ relevance and measurability, and encouraged to suggest new metrics. Main outcome measure The first Portuguese list of KPIs to assess pharmacists’ clinical and support activities performance and quality in hospital pharmacies. Results A total of 136 KPIs were assessed during this study, of which 57 were included in the original list and 79 were later added by the expert panel. By the end of the study, a total of 85 indicators were included in the final list, of which 40 are considered to be saKPI, 39 cpKPI and 6 neither. Conclusion A set of measurable KPIs was established to allow for benchmarking within and between Portuguese hospital Pharmacies and to elevate professional accountability and transparency. Future perspectives include the use of both cpKPIs and saKPIs on a national scale to identify the most efficient performances and areas of possible improvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impacts on practice

-

This work intends to promote the discussion around performance indicators and to raise awareness and know-how on the current and future role of the Hospital Pharmacies, by determining a framework to develop it assessment on a recurrent basis.

-

For the first time in Portugal, a set of relevant and measurable indicators are defined in order to assess hospitals’ pharmacies performance, using a combined nominal group/focus group technique.

-

The definition of these performance indicators is considered to be a landmark in hospital pharmacy in Portugal and it is the first step to the first national study to assess all hospital pharmacies of the NHS.

-

Since an international benchmarking system is not established for hospital pharmacies, it is essential to cultivate an internal culture of activity monitoring and internal benchmarking between similar institutions, using a set of KPI defined by hospital pharmacists, based on the evidence available.

Introduction

Hospital pharmacists strive to continuously maintain and improve medication management and patient pharmaceutical care to the highest possible standards. Their roles include participating in medication management, which encompasses the entire way in which medicines are selected, procured, delivered, prescribed, administered and monitored [1, 2]. These activities are performed whilst ensuring the 7 “rights” are respected: right patient, right dose, right route, right time, and the right drug with the right information and documentation.

Clinical pharmacy is defined as “a health science discipline where pharmacists provide patient care that optimizes medication therapy and promotes health, wellness, and disease prevention” [3,4,5]. Therefore, clinical pharmacy is deemed an integral component of this process, being responsible for ensuring that patients receive the right medicine at the right time by an efficient and economic system [6].

Although traditionally pharmacists were mostly concerned with procuring, dispensing, manufacturing and supplying drugs [2], clinical pharmacy has become so relevant that pharmacists spent an average of 47% of their time on clinical activities, 37% on distribution and 16% on management activities, as shown by an Australian study [7].

In fact, in Portugal, as in other countries, the hospital pharmacy concept lies in the existence of two major areas: support sector and clinical activities [8]. The first integrates management and organization, acquisition and stock management, storage and conservation, repackaging, production/compounding, and distribution. The clinical area involves all the activities related to clinical pharmacy/pharmaceutical care (e.g., therapeutic review, medication reconciliation, pharmaceutical consulting, clinical pharmacokinetics, counselling or pharmacovigilance).

In Portugal, the pharmaceutical profession emerged in the thirteenth century [9]. Out of 15,000 practicing pharmacists, 9% are in hospital pharmacies [8]. Given the evolution of healthcare and patient’s needs and demands, the 2008 Hospital Medicine Program allowed hospital pharmacists to participate and develop quality improvement initiatives, promoting a patient safety culture [8, 10,11,12]

Evidence suggests that when clinical pharmacists integrate the multidisciplinary team, their interventions can help reduce the likelihood of mortality, length of stay, adverse-drug-event prevalence and improve patients’ quality of life [6, 16], by ensuring medication reconciliations/reviews [5, 13,14,15]. Therefore, a way to assess both quality and impact of the services provided to patients is by quantifying and monitoring clinical activities through audits, service reviews, incident reports and surveys to patients, and by ensuring that complaint management and control procedures are in place [5, 13, 17] .

A known strategy to track and continuously assess performance is through the use of clinical pharmacy Key Performance Indicators (cpKPIs) [6]. According to several studies, cpKPIs could be used to evaluate the quality of care [17,18,19], to help define a patients’ healthcare expectations regarding a clinical pharmacist, to allow benchmarking within and between organizations, to elevate professional accountability and transparency [5], and to allow the tracking of the organization’s progress towards achieving predefined goals and standards of care [4, 5]. They also play an important part in rewarding good performance, in improving resource allocation and efficiency, and in identifying and reducing clinical errors, whilst maximizing healthcare outcomes and balancing patient’s wants and needs [17,18,19,20]. Given the wide range of services provided, assessing pharmacists’ productivity and quality of care is somewhat difficult [21, 22]. Thus, it is also relevant to establish KPIs addressed to support activities (saKPI).

Despite the evidence supporting the importance of defining KPIs to quantify pharmacists contribution to patient care [5, 19, 20, 23,24,25,26], three main barriers were identified by several authors regarding their implementation: (i) resistance to change related to documenting clinical activities due to increased workload, practice environment constraints and competing priorities; (ii) disbelief of KPIs’ real benefits, value and existing support from other pharmacists and hospital administrations; and, (iii) uncertainty of how to address quality versus quantity or the influence KPIs may have in the future of pharmacy practice [6, 27,28,29].

Nevertheless, several countries have already started developing their own standard KPIs, such as Australia [13, 26], 30,31,32,33], Belgium [19, 25], Brazil [20, 34, 35], Canada [4, 5, 36, 37], Finland [38], Spain [39, 40], UK [17], USA [41,42,43,44], New Zealand [22, 45], and the Netherlands [46]. However, there is no current international consensus on KPIs [2, 4,5,6, 13, 21, 29].

Aim of the study

In Portugal, most hospital pharmacies only collect some internal data for certification/accreditation purposes or ad-hoc situations. Currently, there is no national standard system for activity monitoring, nor any nationwide framework that enables comparisons/benchmarks amongst pharmacies’ performances regarding their clinical or support activities. Thus, the main goal of this study is to define, for the first time in Portugal, a national set of relevant and measurable cpKPIs/saKPIs to assess the National Health System Hospital Pharmacies’ performance and quality.

Ethics approval

As a service development and evaluation study, it was exempt from formal ethics approval. All study participants were given full information and provided signed, informed consent.

Method

Study design

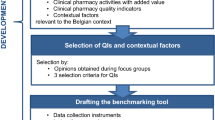

Consensus cpKPI/saKPI were determined using a combined nominal group/focus group technique, which combines the prioritisation process of a standard nominal group technique with the in-depth discussion of a focus group [47]. The expert panel was encouraged to assess both the relevance and measurability of the original candidate KPI, and to suggest new candidate indicators, for five rounds. After each round, an in-person panel meeting was held, promoting in-group discussions about the candidate KPIs and to clarify questions regarding the definition of any new proposed KPI (Fig. 1).

Defining the KPIs

Two stages were developed to define the first list of cpKPI/saKPI: (1) Literature review and exploratory meetings; (2) Expert panel rounds.

-

(1)

Literature review and exploratory meetings

Two investigators (HL and ARL) conducted a comprehensive literature review focusing on KPIs used in other countries. To account for existing national practices, meetings were held with several renown hospital pharmacists, who shared their perspectives on currently implemented practices and metrics. After this process, a list of 57 candidate KPIs was defined.

The annual European Association of Hospital Pharmacists (EAHP) survey is annually deployed to measure the progress, key barriers and drivers of the implementation of their six Statements: (i) Introductory Statements and Governance; (ii) Selection, Procurement and Distribution; (iii) Production and Compounding; (iv) Clinical pharmacy Services; (v) Patient Safety and Quality Assurance; and, (vi) Education and Research. Since several Portuguese hospital pharmacies already participate in the survey [1, 48], each EAHP Statement was divided into several Assessment Areas and specific candidate KPIs were defined to assess each Area.

-

(2)

Expert panel rounds

To reach the final list of KPIs, five rounds with an expert panel were performed from January of 2019 to March of 2020.

Round 1

The first round presented to the expert panel the key project moments, the main goals and methodology, all of which previously defined with the Portuguese Pharmaceutical Society, and the 57 candidate KPIs, categorised by EAHP Statement.

After this round, the expert panel had four weeks to rate each indicator in two different dimensions: Relevance and Measurability. The former was defined as the ability to reflect the hospital pharmacy performance or the clinical pharmacist’s direct impact on patient care, while the latter was defined as the ability to easily collect data to calculate the KPI within the hospital.

Each panel member used a five-point Likert scale to assess both dimensions: 1 = Totally Irrelevant/Totally Impossible; 2 = Not Relevant/Impossible; 3 = Neutral/Neutral; 4 = Relevant/Easy; 5 = Very Relevant/Very Easy.

At the beginning of the study, three criteria were defined by the expert panel to determine which KPIs would be included in the final list: (i) if the average relevance score for each indicator was low (rating equal or lower than 3 points), the indicator would be excluded, regardless the measurability score; (ii) if the average relevance score was high (rating higher than 3 points) and the measurability low, the indicator would be excluded; and, (iii) if the average relevance and measurability scores were high, the indicator would be included in the final list.

Round 2

After collecting all panellist scores and calculating the average score for each indicator, a second in-person meeting was held to present and discuss the results regarding relevance and measurability of the original candidate KPIs. In each in-person meeting, consensus concerning indicators with scores close to cut-off points were obtained by majority.

Round 3

The expert panel was given four weeks to suggest new candidate KPIs per EAHP Statement. Following this time, a third in-person panellist meeting was held for discussion and clarification regarding the proposed KPIs and their definitions.

Round 4

The expert panel was then asked to rate the new set of suggested KPIs according to their relevance and measurability, using the five-point Likert Scale. The fourth in-person round took place after having all the scores calculated for each indicator.

Round 5: Final set of KPIs

Finally, after assessing both original and suggested candidate KPIs, a last in-person meeting was held to present the final list and to define the sources of information available within the hospitals to measure each KPI.

KPI Definition

Concerning the definition of the candidate KPIs, the authors agreed that all should: (i) reflect the current hospital pharmacists activities, (ii) be evidence-based, (iii) be aligned with clinical pharmacists’ goals, objectives and practices, (iv) be feasible to measure, (v) be relevant to clinical outcomes, and (vi) be used across all types of Hospital Pharmacies (e.g., rural, urban, teaching or non-teaching hospitals). A glossary indicating each rational, measurement unit, target-population and data-source was then prepared for each suggested candidate KPI.

The expert panel

A panel of eight experts was specifically selected for this project by the board members of the Portuguese Pharmaceutical Society, considering their professional curricula, expertise, and contributions for the development of clinical pharmacy in Portugal. These experts are renowned hospital pharmacists having also professional responsibilities since they are Pharmaceutical Society representatives and members of pharmaceutical associations in Portugal.

As for their main characteristics, the average age was 48.7 years old, mostly females, with around 25 years of experience as a pharmacist and around 10 years of experience as hospital pharmacy director (Table 1).

The definition of a panel consisting exclusively of pharmacists aims to ensure that the defined cpKPIs/saKPIs are unanimously agreed upon, and that they effectively measure their performance. In an analogy of the Gettysburg Address speech by former U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, this expert panel was created to define the cpKPI/saKPI list for Hospital Pharmacy “of the pharmacists, by the pharmacists, for the pharmacists”.

Results

Round 1 and 2: assessing the original list of the candidate KPIs

Following an extensive literature review, 57 candidate KPIs were included in the original list, categorized into six EAHP Statements (Table 2), where 22 were considered as saKPI, 33 cpKPI and 2 neither.

After assessing their relevance, only two were considered as “not relevant” (rating lower than 3 points) by the expert panel and therefore were excluded.

Regarding measurability, although 21 KPIs were considered relevant (rating equal or higher than 4 points), data collection capability was low. For example, the ‘Number of pharmacists rounds’ or the ‘Number of adverse events reported by patients’ were considered as some of the most relevant KPIs, however, the ability to measure them ranged from 1.5 to 2.1 points. Similarly, the three KPIs rated as ‘Totally Impossible’ to measure (rating equal or lower than 1.3 points) were also considered to be highly relevant (rating equal or higher than 4 points).

Rounds 3 and 4: expert panel suggested candidate KPIs

The following rounds sought not only to include the new suggested candidate KPIs (round 3), but also to assess their relevance and measurability (round 4) (Table 3).

After the third round, the expert panel suggested 79 new KPIs: 37 saKPI, 38 cpKPI and 4 neither.

Concerning their relevance and measurability (round 4), six KPIs were considered as totally relevant (rating 5 points) by all panel members and easily measured (rating equal to or higher than 4 points).

After the fourth round, 26 of the total suggested KPIs were excluded, 5 due to their low relevance and 21 due to their low ability to be measured (rating equal or lower than 3.0 points).

Round 5: defining the final set of KPI

Finally, a last in-person meeting was held with the expert panel to present the final list of KPIs, and to define the sources of information to calculate each metric (round 5).

The expert panel defined a final list with 85 KPIs to assess all six EAHP Statements: 14 to assess the introductory statements; 10 on selection, procurement and distribution; 6 on production and compounding; 16 on clinical pharmacy services; 25 on patient safety and quality assurance; and 14 on education and research (Table 4). Concerning the type of KPI, 40 are saKPIs, 39 cpKPIs and 6 neither.

Discussion

Although being the first study to define a Portuguese set of saKPIs/cpKPIs to assess hospital pharmacy performance and quality based on EAHP Statement, other countries have deployed similar studies, as previously mentioned.

Though some authors argue that setting benchmarks by accreditation bodies or certifications by international organizations is the first step of healthcare quality cycle [49], only one study from Brazil referred to the importance of measuring the existence of updated written operational procedures for all clinical pharmacy activities [34].

About the KPIs included in the second statement, the ‘Drugs stock turnover’ comprises a commonly used criterion for assessing the efficiency of pharmacies’ purchasing and supply chain [26]. Given the importance of this metric, three indicators were defined in the Magarinos-Torres et al. (2007) study to assess the stock turnover, namely the number of medication units lost, the value spent in lost medication, and the existence of updated reports on medication availability [34].

Our expert panel included the highest number of KPIs in the “clinical pharmacy services” statement, which is aligned with the indicators referred across the literature. The KPI ‘Existence of medication reconciliations up to 72 h after admission’ is one of the most frequently mentioned in the literature [4, 5, 17, 19, 26, 45]. Although the time interval defined for reconciliation varies between 24 to 72 h, there is a consensus across the literature that it is highly relevant and measurable, not only by identifying the existence or non-existence of these reconciliations, but also by the importance of quantifying the proportion of patients who received formal documented medication reconciliation at discharge [4, 26].

Aligned with several studies [4, 19, 26, 45], KPIs related to patients’ education and information sharing are highly recommended. In the Lloyd et al. (2017) study, the expert panel argues that patients have to receive written/verbal counselling before discharge, and that they should also receive a document with an accurate medication list detailing any therapy changes [26]. In two other studies, both panel groups defined a specific KPI to measure the proportion of patients who have face-to-face discussions about their medication before discharge [4, 45].

Concerning the clinical pharmacy services, the development of outpatient pharmaceutical consultations was considered an important area of clinical intervention, aiming for medication reconciliation, drug interactions management, adverse reactions detection, patient education among others [50,51,52]. Therefore, outpatient pharmacy and consultation has become an important part of pharmacists’ tasks [52, 53].

As for the statement patient safety, although the number of adverse events reported by staff and/or by patients is one of the KPIs most frequently referred to in the literature, this indicator can assume different definitions. For example, in a study from Brazil, this KPI is mentioned as ‘Number of problems that occurred related to medications’ and ‘Number of problems related with medications identified and notified’ [34]; in a study from Belgium, it’s referred to as ‘Number of interventions accepted and activities performed to prevent, detect, assess, manage, report, and/or document adverse drug reactions/Number of patients with a pharmaceutical record’ [19]. Given that the Portuguese National Pharmacovigilance System requires pharmacists to report adverse events, the expert panel included a specific KPI to quantify the ratio between reported adverse events and number of discharges/ outpatients followed.

Finally, all panel members agreed that pharmacist’s continuous education was one of the key elements to ensure the quality of care and should therefore be assessed. Similarly, an Australian study concluded that continuous training is part of the learning process of clinical pharmacists in 239 public hospital pharmacy services [7]. Thus, it is not surprising that the cpKPI ‘Time spent on training’ was considered relevant by our expert panel, as well as by several studies [26, 34, 38]. According to this last study, participation in continuing long-term higher education usually includes areas such as expertise in ward pharmacy, medication reviews, or accreditation for comprehensive medication reviews [38].

The key outcome of this study was the definition of the first list of national KPIs to assess hospital’s pharmacists’ performance. Additionally, the study design enabled an important advantage, given the characteristics of the expert panel, which included individuals who feel more comfortable participating in face-to-face meetings rather than in multi-round surveys. The use of a combined nominal group/focus group technique ensured equal participation amongst panellists and gave them the opportunity to explore diverging opinions throughout the group discussions. Finally, when implemented at the national level, we expect that these KPIs will improve transparency and accountability among hospital pharmacies and heighten the quality of care.

As for potential weaknesses, the exclusion of relevant KPIs by the expert panel based on the low measurability may limit the scope of assessment. However, since the indicators included in the final list reflect the dichotomy between high relevance and measurability, it is expected that its adoption by hospital pharmacies and by the Ministry of Health may become a reality before long.

Conclusion

Defining these 85 cpKPIs/saKPI is a first step towards assessing Hospital Pharmacy performance and quality. Major challenges are expected to arise during the implementation of these KPIs at a national level. Some of which include: defying the status quo, increasing workload in data collection, ensuring data quality and, most importantly, communicating across all players that KPI measurement to monitor performance in hospital pharmacists’ clinical and support activities will allow better activity assessment, leading to an improvement in inpatient and outpatient quality of care, enabling continuous future development and planning with greater certainty.

Despite this study’s major contribution to hospital pharmacists’ clinical and support activities, future research should focus on gathering external stakeholders’ feedback on relevant KPIs, developing consensus indicators for outpatient care or for subspecialty areas, which require different and/or supplemental metrics to help improve quality of patient care and further develop clinical pharmacy practice. Thus, future research ought to contribute to a more complete understanding of KPIs role in this field.

References

Horák P, Underhill J, Batista A, Amann S, Gibbons N. EAHP European statements survey 2017, focusing on sections 2 (Selection, Procurement and Distribution), 5 (Patient Safety and Quality Assurance) and 6 (Education and Research). Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2018;25(5):237–44.

Onatade R, Appiah S, Stephens M, Garelick H. Evidence for the outcomes and impact of clinical pharmacy: context of UK hospital pharmacy practice. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2018;25(1):21–8.

ACCP. The definition of clinical pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(6):816–7.

Fernandes O, Gorman SK, Slavik RS, Semchuk WM, Shalansky S, Bussières JF, et al. Development of clinical pharmacy key performance indicators for hospital pharmacists using a modified delphi approach. Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49(6):656–69.

Lo E, Rainkie D, Semchuk WM, Gorman SK, Toombs K, Slavik RS, et al. Measurement of clinical pharmacy key performance indicators to focus and improve your hospital pharmacy practice. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2016;69(2):149–55.

Doucette D, Millin B. Should key performance indicators for clinical services be mandatory? Can J Hosp Pharm. 2011;64(1):55–7.

O’Leary KM, Allinson YM. Pharmacy clinical and distribution service delivery models in Australian public hospitals. J Pharm Pract Res. 2004;34(2):114–21.

Costa F, Paulino E, Farinha H. Pharmacy practice in Portugal. In: Babar Z, editor. Encyclopedia of pharmacy practice and clinical pharmacy. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2019. p. 569–85.

PPS. Portuguese Pharmaceutical Society: Pharmacists in Numbers [Farmacêuticos em Números]. 2021. https://www.ordemfarmaceuticos.pt/pt/numeros/. Accessed 12.04.2021.

DL 44/204. Decrete-Law Num. 44/204: General Regulation of Hospital Pharmacy. 1962. https://www.infarmed.pt/documents/15786/1068150/decreto_lei_44204-1962.pdf. Accessed 12.04.2021.

Law 46/2004. Legal regime applicable to the conduct of clinical trials with medicinal products for human use. 2004. https://dre.pt/application/file/a/480459. Accessed 12.04.2021.

DL 108/2017. Decrete-Law Num. 108/2017: Pharmaceutical career regime in public business entities and health partnerships. 2017. http://www.cmvm.pt/pt/Legislacao/LegislacaoComplementar/OrganismosdeInvestimentoColetivo/Documents/Lei 104.2017 de 30 de Agosto.pdf. Accessed 12.04.2021.

Lloyd GF, Bajorek B, Barclay P, Goh S. Narrative review: status of key performance indicators in contemporary hospital pharmacy practice. J Pharm Pract Res. 2015;45(4):396–403.

Rotta I, Salgado TM, Silva ML, Correr CJ, Fernandez-Llimos F. Effectiveness of clinical pharmacy services: an overview of systematic reviews (2000–2010). Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37(5):687–97.

Monnier AA, Schouten J, Le Maréchal M, Tebano G, Pulcini C, Stanic Benic M, et al. Quality indicators for responsible antibiotic use in the inpatient setting: a systematic review followed by an international multidisciplinary consensus procedure. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(6):30–9.

Lee H, Ryu K, Sohn Y, Kim J, Suh GY, Kim EY. Impact on Patient Outcomes of Pharmacist Participation in Multidisciplinary Critical Care Teams: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med. 2019. 47(9):1243–50.

Aljamal MS, Ashcroft D, Tully MP. Development of indicators to assess the quality of medicines reconciliation at hospital admission: an e-delphi study. Int J Pharm Pract. 2016;24(3):209–16.

Nau DP. Measuring pharmacy quality. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2009;49(2):154–63.

Cillis M, Spinewine A, Krug B, Quennery S, Wouters D, Dalleur O. Development of a tool for benchmarking of clinical pharmacy activities. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40(6):1462–73.

Lima TM, Aguiar PM, Storpirtis S. Development and validation of key performance indicators for medication management services provided for outpatients. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2019;15(9):1080–7.

Gupta SR, Wojtynek JE, Walton SM, Botticelli JT, Shields KL, Quad JE, et al. Monitoring of pharmacy staffing, workload, and productivity in community hospitals. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(18):1728–34.

Millar T, Sandilya R, Tordoff J, Ferguson R. Documenting pharmacist’s clinical interventions in New Zealand hospitals. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30(1):99–106.

Rough SS, McDaniel M, Rinehart JR. Effective use of workload and productivity monitoring tools in health-system pharmacy, part 1. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2010;67(4):300–11.

Rough SS, McDaniel M, Rinehart JR. Effective use of workload and productivity monitoring tools in health-system pharmacy, part 2. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2010;67(5):380–8.

Somers A, Claus B, Vandewoude K, Petrovic M. Experience with the implementation of clinical pharmacy services and processes in a university hospital in Belgium. Drugs Aging. 2016;33(3):189–97.

Lloyd GF, Singh S, Barclay P, Goh S, Bajorek B. Hospital pharmacists’ perspectives on the role of key performance indicators in Australian pharmacy practice. J Pharm Pract Res. 2017;47(2):87–95.

Boyle TA, Bishop AC, Mahaffey T, MacKinnon NJ, Ashcroft DM, Zwicker B, et al. Reflections on the role of the pharmacy regulatory authority in enhancing quality related event reporting in community pharmacies. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2014;10(2):387–97.

Gagnon MP, Nsangou ÉR, Payne-Gagnon J, Grenier S, Sicotte C. Barriers and facilitators to implementing electronic prescription: a systematic review of user groups’ perceptions. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(3):535–41.

Minard LV, Deal H, Harrison ME, Toombs K, Neville H, Meade A. Pharmacists’ perceptions of the barriers and facilitators to the implementation of clinical pharmacy key performance indicators. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0152903.

Larmour I. Performance indicators in hospital pharmacy management. Aust J Hosp Pharm. 1996;26(1):89–92.

Aln A. Continuity in medication management: South Australian APAC key performance indicators for hospitals participating in pharmaceutical reform. Government of South Australia; 2010. https://www.academia.edu/13383713/Continuity_in_medication_management_South_Australian_APAC_key_performance_indicators_for_hospitals_participating_in_pharmaceutical_reform. Accessed 10.04.2020.

ACSQHC. National Quality Use of Medicines Indicators for Australian Hospitals. Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care and NSW Therapeutic Advisory Group Inc. 2014. ISBN 978–1–921983–78–8. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/SAQ127_National_QUM_Indicators_V14-FINAL-D14-39602.pdf. Accessed 15.04.2020.

ACHS. The Australian Council on Healthcare Standards: Clinical Indicator Program Information. 2020. https://www.achs.org.au/media/153524/achs_2020_clinical_indicator_program_information.pdf. Accessed 01.07.2020.

Magarinos-Torres R, Osório-de-Castro CG, EdaisPepe VL. Critérios e indicadores de resultados para a farmácia hospitalar brasileira utilizando o método Delfos [Establishment of criteria and outcome indicators for hospital pharmacies in Brazil using Delphos]. Cad Saude Publica. 2007;23(8):1791–802.

Lima RF, De Toledo MI, Silva PHD, De Naves JOS. Evaluation of pharmaceutical services in public hospital pharmacies of Federal District-Brazil. Farm Hosp. 2018;42(3):108–15.

Nigam R, Mackinnon NJ, David U, Hartnell NR, Levy AR, Gurnham ME, et al. Development of Canadian safety indicators for medication use. Healthc Q. 2008;11(3):47–53.

Fernandes O, Toombs K, Pereira T, Lyder C, Mejia A, Shalansky S, et al. Canadian Consensus on Clinical Pharmacy Key Performance Indicators: Quick Reference Guide. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Society of Hospital Pharmacists. 2015. https://cshp.ca/document/4592/CSPH-Can-Concensus-cpKPI-QuickReferenceGuide_June_2017.pdf. Accessed 15.05.2020.

Schepel L, Aronpuro K, Kvarnström K, Holmström AR, Lehtonen L, Lapatto-Reiniluoto O, et al. Strategies for improving medication safety in hospitals: evolution of clinical pharmacy services. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2019;15(7):873–82.

de Lara SN, Noguera IF, Gaude VL, Briz EL, Pascual MJM, Andrés JLP. Programa de calidad aplicado a la sustitución de medicamentos no incluidos en la Guía Farmacoterapéutica del hospital [Therapeutic interchange of drugs not included in the hospitaĺs pharmacotherapeutic guide: a quality program]. Farm Hosp. 2004;28(4):266–74.

Fernández-Megía MJ, Noguera IF, Sanjuán MM, Andrés JLP. Monitoring the quality of the hospital pharmacoterapeutic process by sentinel patient program. Farm Hosp. 2018;42(2):45–52.

Rozner S. Developing and Using Key Performance Indicators: A Toolkit for Health Sector Managers. 2013. https://www.hfgproject.org/developing-key-performance-indicators-toolkit-health-sector-managers/. Accessed 15.05.2020.

Pedersen CA, Schneider PJ, Scheckelhoff DJ. ASHP national survey of pharmacy practice in hospital settings: monitoring and patient education, 2015. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(17):1307–30.

Pedersen CA, Schneider PJ, Scheckelhoff DJ. ASHP national survey of pharmacy practice in hospital settings: dispensing and administration, 2014. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(13):1119–37.

Pedersen CA, Schneider PJ, Scheckelhoff DJ. ASHP national survey of pharmacy practice in hospital settings: Prescribing and transcribing, 2016. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74(17):1336–52.

Ng J, Harrison J. Key performance indicators for clinical pharmacy services in New Zealand public hospitals: stakeholder perspectives. J Pharm Heal Serv Res. 2010;1(2):75–84.

Teichert M, Schoenmakers T, Kylstra N, Mosk B, Bouvy ML, van de Vaart F, et al. Quality indicators for pharmaceutical care: a comprehensive set with national scores for Dutch community pharmacies. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(4):870–9.

Manera K, Hanson CS, Gutman T, Tong A. Consensus methods: nominal group technique. In: Liamputtong P, editor. Handbook of research methods in health social sciences. Singapore: Springer; 2019. p. 737–50.

Horák P, Gibbons N, Sýkora J, Batista A, Underhill J. EAHP statements survey 2016: sections 1, 3 and 4 of the European statements of hospital pharmacy. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2017;24(5):258–65.

Alkhenizan A, Shaw C. Impact of accreditation on the quality of healthcare services: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Saudi Med. 2011;31(4):407–16.

Milone AS, Philbrick AM, Harris IM, Fallert CJ. Medication reconciliation by clinical pharmacists in an outpatient family medicine clinic. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2014;54(2):181–7.

Andrus M, Anderson A. A retrospective review of student pharmacist medication reconciliation activities in an outpatient family medicine center. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2015;13(1):1–6.

Almanasreh E, Moles R, Chen TF. The medication reconciliation process and classification of discrepancies: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82(3):645–58.

Franco JA, Terrasa S, Kopitowski K. Medication discrepancies and potentially inadequate prescriptions in elderly adults with polypharmacy in ambulatory care. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2017;6(1):78–82.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all members of the expert panel, namely Ana Margarida Freitas (Portuguese Association of Hospital Pharmacists), Armando Alcobia (Hospital Pharmacy Director in Hospital Garcia de Orta), Catarina Oliveira (Portuguese Association of Hospital Pharmacists), Margarida Pereira (Portuguese Society of Healthcare Pharmacists), Patrocínia Rocha (Hospital Pharmacy Director in Centro Hospitalar Universitário do Porto), Paula Campos (Specialty College of Hospital Pharmacy) and Pedro Soares (Hospital Pharmacy Director in Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de São João). Finally, to Maria Pyro and Catarina Correia for their support in the linguistic revision of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The literature review and the rounds with the experts had the financial support of Gilead Sciences (Project Number 2497421) and Novartis (Project Number 2720975). Nevertheless, this funding had no influence on the writing of the manuscript, which is the sole responsibility of the authors.

Conflicts of interest

HL and ARL are IQVIA employees, HF and APM are board members of the Portuguese Pharmaceutical Society.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lopes, H., Lopes, A.R., Farinha, H. et al. Defining clinical pharmacy and support activities indicators for hospital practice using a combined nominal and focus group technique. Int J Clin Pharm 43, 1660–1682 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-021-01298-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-021-01298-z