Abstract

Background Tobacco use is a leading preventable cause of morbidity and mortality globally. Clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of tobacco use dependence are of varied scope and quality, making it challenging for users to select and apply recommendations. Objective The study objective is to identify and critically appraise the quality of existing clinical practice guidelines for tobacco cessation. Setting The study occurred between collaborative academic institutions located in Qatar and New Zealand. Methods A systematic literature search was performed for the period 2006–2018 through the following databases: PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, ISI Web of Science, Scopus, National Guideline Clearing House, Campbell Library, Health System Evidence, Joanna Briggs Institute Evidence-Based Practice Database, Academic Search Complete, ProQuest, PROSPERO, and Google Scholar. Relevant professional societies’ and health agencies’ websites were also searched. Two reviewers independently extracted and assessed guidelines’ quality using Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) instrument. Main outcome measure Standardized domain scores according to the AGREE II instrument. Results 7741 hits were identified. After removing duplicates and screening, 24 guidelines were included. Highest guideline quality was for National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline with an overall ranking score of 87.56% and least quality was for Japanese Circulation Society Joint Working Group with an overall score of 29.34%. Domain 4 of AGREE II (clarity of presentation) had the highest average quality score (70.95%), while the lowest average quality scores were for Domain 2 (Rigour of Development) (50.21%) and Domain 5 (Applicability) (45.05%). Conclusion Seven guidelines were judged to be of high quality (overall score of ≥ 70%). Future guidelines for tobacco dependence treatment should use rigorous methods of development and provide applicable recommendations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impact of findings on practice

-

The study identified 25 eligible tobacco cessation Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) of which seven guidelines were considered of high quality.

-

In order to improve the application of the best evidence-based recommendations in clinical practice, future tobacco cessation guidelines developers should apply robust methodologies based on quality criteria such as AGREE II criteria in developing and reporting the guidelines.

-

Before adaptation in national practice, clinicians should rigorously appraise the quality of CPGs and assess their applicability to their context taking into consideration several factors including cultural, financial, health system and environmental factors

Introduction

Tobacco use and dependence is a leading preventable cause of morbidity and mortality globally, and is strongly linked to numerous diseases and healthcare burden [1]. Worldwide, the age standardized prevalence of daily smoking was 25% for men and 5.4% for women from 1990 to 2015 [2]. Although concerted efforts have been put in place to reduce the global smoking prevalence, many countries continue to record high smoking rates, resulting in increased disease burden and healthcare expenditures [2, 3]. Tobacco cessation interventions play an important role in addressing tobacco-related health risks and mortality. Studies have shown that when pharmacotherapy and behavioral interventions are used among adults either singly or in combination, this results in higher success rates [4,5,6,7]. Therefore, the role for healthcare providers in implementing tobacco cessation interventions within their clinical practice settings becomes unequivocally important. Clinicians use tobacco cessation tools and resources such as clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) to provide tobacco use dependence management.

CPGs are important resources used by clinicians when making evidence-based decisions to improve the quality and outcomes of the care delivered to patients. CPGs are attractive due to their concise nature and capacity to provide consistent care by clinicians [8]. On the other hand, CPGs have their limitations when recommendations are influenced by expert opinion and practice experiences. In addition, CPGs are adopted into patient care without undergoing robust critical appraisal to assess their validity and methodological quality [9]. Evidence-based CPGs for the treatment of tobacco use dependence are of varied scope and quality, making it challenging for clinicians to select and apply the best evidence-based recommendations. Having high quality critically appraised tobacco cessation guidelines is important for clinicians to apply the best evidence when treating their patients for tobacco use dependence.

Aim of the study

This study aimed to critically appraise current tobacco cessation guidelines and to determine the ones with the highest quality for potential utilization in clinical practice.

Ethics approval

No approval was necessary.

Method

Search strategy and identification of guidelines

A protocol for the systematic review was developed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [10] and other best practices. The protocol was registered and published on PROSPERO at the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, UK (CRD42018086709). We conducted a systematic literature search to identify tobacco cessation CPGs. The following electronic databases were searched to identify eligible articles published from January 2006 to June 2018: PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, ISI Web of Science, Scopus, National Guideline Clearing House, Campbell Library, Health System Evidence, Joanna Briggs Institute Evidence-Based Practice Database, Academic Search Complete, ProQuest, PROSPERO, and Google Scholar. In order to retrieve relevant guidelines, search terms were combined from four different categories using Boolean operators (Table 1). The keywords were customized to each database specific indexing terms such MeSH terms in PubMed.

Other resources identified such as relevant articles were manually reviewed to further identify additional guidelines not found in the electronic searches. In addition, relevant guidelines’, professional societies’ (cancer, cardiovascular, lung diseases, tobacco and substance abuse, addiction), and government agencies’ websites were searched for relevant tobacco cessation guidelines. These include: National Guideline Clearing House; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE); World Health Organization (WHO); US Center for Disease Control (CDC); US Department of Health and Human Service (USDHHS); clearing houses of Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom; International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (IUATLD); smoking cessation guidelines of cancer, cardiovascular, and respiratory diseases [examples include National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN guidelines)]. All search results were imported into EndNote® X7 reference management software. Each electronic database or website was assigned to two of the study investigators who independently searched the database/website and combined the search results. Duplicates were removed prior to screening.

Eligibility criteria and guidelines selection

CPGs were eligible for inclusion if they provide recommendations for the treatment of tobacco use dependence (pharmacologic and/or non-pharmacologic). We included only the most recent version of each available CPG published from 2006 to 2018. Furthermore, guidelines targeting specific populations (e.g. tuberculosis, pregnant women, COPD) were included in the review if they were exclusively about tobacco dependence treatment in the specific sub-populations. Guidelines for related conditions such as asthma, COPD, cardiovascular diseases, and tuberculosis which contain tobacco use treatment or smoking cessation as part of the guidelines (e.g. a section on tobacco dependence treatment within the guideline) were excluded from the review. In addition, guidelines were excluded if they were non-English, non-peer reviewed, or published prior to 2006 without full updates within 2006–2018. Guidelines were also excluded if recommendations were provided with no level of evidence or no grades of recommendations assigned to them. Reviews, letters, editorials, and commentaries about published CPGs were also excluded. However, executive summaries and other supplementary documents were marked as supporting resources for any additional relevant information during data extraction.

Titles and abstracts from the electronic searches were independently screened by two reviewers for potential eligibility using the above predefined eligibility criteria. Furthermore, two independent reviewers read the full-text of each CPG identified from the title/abstract screening for inclusion in the review. Discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved through discussion at all stages of search and screening process. In case of non-consensus, a third reviewer was consulted.

Data extraction

We extracted information related to the characteristics of each CPG document including the publisher, authors, year of publication, funding source, organization involved in the CPG development, target population and/or subpopulations, and the guidelines development methodology. To increase the validity and consistency of the extracted data, two reviewers independently extracted the information and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Critical appraisal and quality assessment of the included guidelines

The quality of each of the included tobacco cessation CPGs was assessed by two independent reviewers. Seven reviewers conducted the quality appraisals. The CPGs were assessed using the AGREE II (Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation II) instrument [11]. This instrument is widely used for CPGs development, reporting, and evaluation. It contains six constructs with 23 evaluation criteria graded on a seven-point Likert type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). The six constructs of the AGREE II include: (1) scope and purpose, (2) stakeholder involvement, (3) rigor of development, (4) clarity and presentation, (5) applicability and, (6) editorial independence. All reviewers read the AGREE II User Manual to standardize and guide the appraisal process. In addition, several of the reviewers had familiarity and experience with the use of the AGREE II instrument. One investigator (KW) had previously published studies using the AGREE II instrument and was available for consult by other reviewers, if needed. All investigators had clinical and/or research experience in the field of tobacco dependence and its treatment.

Each CPG was appraised by two independent assessors using the AGREE II instrument. Scores were assigned for each of the 23 criteria in a shared Excel spread sheet. The project leader (MH) collected and combined all the assessments in another master Excel spreadsheet. Weighted domain scores were calculated as described in the AGREE II User Manual using Microsoft Excel. Average domain scores for each guideline were also calculated. In addition to the items assessment, for each CPG, each of the two assessors judged the CPG as recommended, recommended with modifications, or not recommended (as per AGREE II criteria). In case of any disagreement in the endorsements, the two raters discussed in a face-to-face meeting and resolved the discrepancies through consensus or adjudication with a third reviewer. Agreement was calculated between the two reviewers for the appraised items of each guideline using two-way random (absolute agreement) Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC). The ICC scores and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using IBM SPSS statistics software version 22.

Results

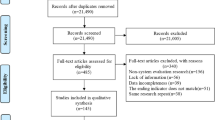

Following the search of the databases, 7715 records were identified in addition to 26 records identified through organizational websites and systematic review references. After removing duplicates and screening (titles, abstracts, full-texts), a total of 24 guidelines related to tobacco cessation that satisfied the study eligibility criteria were identified and evaluated (Fig. 1).

Table 2 describes the characteristics of the CPGs included in the review. The 24 guidelines developed by a wide range of organizations (from governmental to professional bodies) were published between 2006 and 2018. Different sources of guideline-development funding were reported; some guidelines were sponsored by pharmaceutical companies, while others received governmental funding [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Two guidelines were sponsored by Pfizer, one guideline by GalaxoSmithKline, and one guideline by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc as unrestricted grants while many did not report the funding source [17, 20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. All the included guidelines were targeted to healthcare providers and focused on patients who are tobacco smokers. Some guidelines included recommendations related to subpopulations including: children and teenagers (14 guidelines) [13, 14, 16, 17, 19, 22, 24,25,26, 28, 30,31,32,33]; patients with mental illnesses (12 guidelines) [13, 14, 16, 17, 19, 24, 25, 28, 30,31,32,33]; and pregnant women (13 guidelines) [13, 14, 16, 17, 19, 24,25,26, 28, 31,32,33,34]. Moreover, four guidelines covered patients undergoing surgical interventions as a subpopulation [17, 22, 30, 33], while two guidelines included prisoners [14, 25].

The majority of the guidelines (n = 14) [12, 15, 16, 18, 19, 21, 23, 27, 29,30,31,32, 34, 35] reported implementing a systematic search for primary literature through multiple resources and databases. The NICE guidelines utilized the highest number of databases and organizations’ websites compared to other guidelines [21, 23, 29]. The NCCN guideline searched only one database in addition to consensus meetings [27]. Other CPGs evaluated did not report the sources of the evidence used [13, 14, 17, 20, 22, 24,25,26, 28, 33]. Other characteristics of the reviewed CPGs are provided in Table 2.

The quality assessment of the 24 included guidelines is provided in Table 3 Seven guidelines [18, 19, 21, 23, 29, 34, 35] were judged to be of high quality with an overall score of > 70% based on the AGREE II instrument. The NICE guideline [29] had the highest AGREE II quality score, while the guidelines by the Japanese Circulation Society (JCS) Joint Working Group and the National Center for Smoking Cessation and Training (NCSCT) had the lowest AGREE II quality scores [22, 25]. Regarding the overall scores of guidelines on the domains of the AGREE II instrument, the highest scores were for Domain 4 (clarity of presentation) (70.95%) and Domain 2 (Stakeholders’ involvement) (56.37%). The domain with the lowest average score was Domain 5 (Applicability) (45.05%) as shown in Fig. 2.

Considering the overall recommendations, two guidelines [25, 28] were not recommended, while six were recommended with no modifications [18, 19, 21, 27, 29, 35].

The ICC was calculated for each guideline and it reflected a very strong agreement between the reviewers, except for two guidelines [18, 23]. The average ICC score across all guidelines was 0.817 (range 0.221–0.975).

Discussion

Tobacco use is one of the major public health threats worldwide. It is a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, cancers, and deaths [36]. In the last several years, several efforts have been exerted to reduce the burden of this epidemic. Despite these, a systematic and an organized approach for the treatment of tobacco use dependence is needed in different healthcare settings. Several CPGs for the treatment of tobacco use are developed and available for potential clinical use. However, data regarding the quality, rigour of development, and applicability of these guidelines are scarce. This review attempted to identify and appraise existing CPGs for tobacco cessation.

Twenty-four CPGs for the treatment tobacco use dependence met the eligibility criteria for the study and were assessed using AGREE II criteria. There was a great variability between the different guidelines in terms of their quality based on items and domains assessment. Seven guidelines were considered of high quality with an overall score of > 70% [18, 19, 21, 23, 29, 34, 35]. The guideline with the highest overall ranking score (87.56%) was the NICE guideline for stop smoking interventions and services [29]. While this guideline excelled in all domains of the Agree II criteria as compared to other guidelines, it is plausible that the developer had a superior reporting system. It is worth noting that before implementing any of the guideline recommendations, it is important to see the adaptability of these recommendations to the context of the practice setting. The guidelines with the lowest overall quality scored had consistently low scores across all domains, especially in stakeholder involvement, rigor of development, and editorial independence domains.

The domains with the lowest quality appraisal scores were ‘rigour of development’ with an average score of 50.21% and ‘applicability’ with an average score of 45.05%. These findings are consistent with previous studies’ findings [37,38,39]. There was agreement on only six guidelines to be recommended for use without modifications [18, 19, 21, 27, 29, 35], while 11 guidelines were recommended for use in practice with modifications [12,13,14,15, 20, 23, 24, 26, 30, 31, 34].

On the ‘rigour of development’ domain, which is of utmost importance for the quality of guidelines, only two guidelines scored over 90%. They are the NICE guidelines for “smoking: stopping in pregnancy childbirth” and NICE guideline for “stop smoking interventions” [21, 29]. Of the 24 guidelines, 11 scored less than 50% on this domain [13, 14, 16, 17, 20, 22, 25, 26, 28, 32, 33]. Under the “rigour of development” domain in the AGREE II tool, there are eight items: use of systematic methods to search for evidence, description of criteria used for selecting the evidence, description of strengths and limitations of evidence body, description of methods used for formulating recommendations, consideration of benefits, side effects, and risks in formulating recommendations, having an explicit link between recommendations and supporting evidence, review of the guideline by experts prior to its publication and provision of a procedure for updating the guideline [11]. The items with the lowest scores were in relation to the description of criteria used for selecting the evidence, description of the methods used for formulating guideline recommendations and provision of a procedure for updating the guideline. For instance, 12 guidelines did not explicitly describe the criteria that they have used for including/excluding evidence [13, 14, 16, 17, 20, 22, 24,25,26, 28, 32, 33], 11 guidelines did not describe what methods or systems were adopted to reach the final guideline recommendations and decisions [12,13,14, 17, 20, 22, 25, 26, 28, 32, 33], and 15 did not state the procedure for updating the guidelines with the latest research evidence [13,14,15,16,17, 20, 22, 24,25,26, 28, 30, 32, 33, 35]. On the other hand, the majority of the guidelines had explicitly added the link between the guideline recommendations and the research evidence based on which the guidelines have made their recommendations. In addition, in most instances, guidelines summarized their recommendations in tables along with the strength ratings of the evidence. Having clinical guidelines of high methodological rigor is crucial [8, 40]. There is a need to develop tobacco cessation guidelines while applying rigorous methodologic strategies. Without describing the exact criteria and methods used to generate the evidence, the users of guidelines would not be able to decide whether the recommendations are built on robust or weak evidence. Furthermore, guidelines should include a system to monitor the updates in evidence to ensure that recommendations are pertinent and timely [41].

In relation to the applicability of guidelines, the highest score obtained was for NICE guidelines for stop smoking interventions with a score of 81.25% [29]. Of the 24 guidelines assessed, 14 guidelines scored less than 50% [12, 14,15,16,17, 20, 22, 26,27,28, 31,32,33,34]. This domain is largely based on the availability of implementation tools, presence of cost analyses, and resource descriptions required for implementation. In many cases, these considerations may not be fully understood before publication and may not be applicable to all settings where the guideline may be implemented. It is likely, for example, that costs and resources of implementation may differ between institutions, healthcare settings, cities, jurisdictions, and countries [11]. The item with the lowest score under this domain was for the resource implications of applying the recommendations. Eleven guidelines did not identify the resources that are required to apply the recommendations [14, 16, 17, 19, 22, 26, 28, 31,32,33,34]. These recourses could be financial, human or physical resources. The item with the second lowest score was for inclusion of monitoring and/or auditing criteria for guideline implementation [12, 15, 16, 21, 22, 26, 28, 31, 32]. Furthermore, 6 guidelines scored poorly on the item related to the provision of advice and/or tools on how to implement recommendations in practice [12, 16, 20, 26, 28, 32]. Guidelines are not self-implementable and should be adapted to the context of the setting where they are going to be applied taking into consideration the setting’s cultural, financial and environmental factors. Evidence suggests that it is expected that clinicians and patients would benefit from guidelines containing application tools [42]. These tools could overcome many of the patient, provider, institutional and system-level barriers that could face guideline implementation. Guidelines should also include explicit criteria that originate from the main guideline recommendations to help monitoring and measuring the application of the guideline recommendations.

The guidelines that scored the highest on the domain of “scope and purpose” were WHO recommendations for the prevention and management of tobacco use and second-hand smoke exposure in pregnancy [18], NICE guideline for stopping smoking in pregnancy and after childbirth [21], and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement [34]. These guidelines explicitly stated the objectives of the guidelines, and the patient population to whom the guidelines can be applied. While four out of 24 guidelines did not clearly describe the scope and objectives of the guidelines, their benefits, and their outcomes [24, 28, 32, 33], and targeted population [25, 28, 33, 35].

In terms of “stakeholder involvement” domain, the overall average score for the domain was 56.37%. The top performing guidelines for this domain were the Clinical Practice Guideline for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence by the U.S. Public Health Service [35] with a score of 94.44%, NICE guidelines for stopping smoking in pregnancy and after childbirth [21] with a score of 100%, and NICE Stop smoking interventions and services [29] with a score of 97.22%. On the other hand, 10 guidelines scored less than 50% on this domain; for these guidelines, information about the stakeholder(s) involved in developing the guideline was not clear. In addition, the opinions, experiences and expectations of the target population or patients were not sought and the target users of the guideline were not defined. It is strongly recommended that the stakeholders’ opinions especially of patients would be sought when developing guideline recommendations. Involvement of patients in the decision-making process is associated with improved application of guidelines and better health outcomes [43].

In terms of clarity of presentation, the key recommendations in 15 out of the 24 guidelines were clearly either presented as a separate table or textually embedded within the guidelines. Although important for readability and usability of the guideline, it could be argued that other domains (e.g. rigour of development) may be of greater importance to guideline quality. As for editorial independence, to avoid any potential for bias, guideline developers should demonstrate that the views of the funding body have not influenced the content of the guideline and should state any conflict of interest they may have. Eight guidelines did report these two items, respectively [17, 20, 22, 24,25,26, 28] and [14, 16, 17, 20,21,22, 25, 26].

This study has implications for practice including pharmacy practice and future research. In terms of practice, users of guidelines, especially clinicians and pharmacists, should be aware of the commonly identified issues raised by this study, in order to best assess the appropriateness of adapting guidelines in practice. Users including pharmacists should also be aware of specific flaws and limitations of any guideline, specifically if these occur in domains of great importance to their population (e.g. patient preferences vs. inclusion of implementation tools). Moreover, pharmacy organizations should carefully appraise the quality of smoking guidelines before endorsement. From research perspective, the barriers to creating guidelines that are deemed of high quality by the AGREE II criteria should be explored with respect to smoking cessation. It could be possible, for example that the quality of evidence available as a whole is not at the same level as other clinical conditions. In such cases, domain scores will likely be inevitably lower and beyond the control of the guideline developer. Future research should focus on identifying how the use of AGREE II criteria in guidelines creation and reporting may influence guideline development, guideline implementation by practitioners, and any effects on patient care decisions.

This study has some limitations some of which are inherent to any systematic review. The literature search may not have identified all available guidelines on tobacco dependence treatment. However, the extensiveness of the search and inclusion of supplementary search strategy in addition to searching electronic databases might have resulted in identifying all major guideline that were available in the published literature. The second limitation is that we only included guidelines published in English. Therefore, guidelines published in other languages were excluded and not assessed. Furthermore, as per the AGREE II guidelines, it is preferred to have four reviewers per guideline; however, due to the small number of study investigators, only two investigators independently reviewed each guideline. This may not be a limitation, however, as the agreement between raters was high. Our findings were consistent with previous studies and this likely reflects the robustness of the AGREE II tool.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the systematic search yielded 24 clinical practice guidelines that targeted tobacco cessation. Seven guidelines were considered of high quality with an overall score of over 70% based on the AGREE II instrument. Clarity of presentation was the main area of strength in these guidelines. However, the rigour of development and applicability were the major weaknesses in these guidelines. There is a need to improve the guideline development process and reporting in the field of tobacco cessation. Future developers of guidelines should develop guidelines in line with the AGREE II domains and items [11]. Description of the criteria used for selecting evidence and of the methods used for formulating guideline recommendations and explanation of the process for updating guidelines should be included. Seeking the patients’ opinions and expectations and inclusion of application tools for guidelines’ implementation to the daily healthcare practice should also be considered to improve the quality of guidelines.

References

West R. Tobacco smoking: health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychol Health. 2017;32(8):1018–36.

GBD 2015 Tobacco Collaborators. Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2017;389(10082):1885–906.

Ekpu VU, Brown AK. The economic impact of smoking and of reducing smoking prevalence: review of evidence. Tob Use Insights. 2015;8:1–35.

Patnode CD, Henderson JT, Thompson JH, Senger CA, Fortmann SP, Whitlock EP. Behavioral counseling and pharmacotherapy interventions for tobacco cessation in adults, including pregnant women: a review of reviews for the U.S. preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(8):608–21.

Cahill K, Stevens S, Perera R, Lancaster T. Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: an overview and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5:Cd009329.

Coleman T, Chamberlain C, Davey MA, Cooper SE, Leonardi-Bee J. Pharmacological interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;12:Cd010078.

Stead LF, Lancaster T. Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:Cd008286.

Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Clinical guidelines: potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318(7182):527–30.

Feder G, Eccles M, Grol R, Griffiths C, Grimshaw J. Clinical guidelines: using clinical guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318(7185):728–30.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

Brouwers M, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182(18):E839–42.

Reis I, Fortuna P, Ascenção R, Costa J, Bugalho A, Carneiro AV. Clinical practice guideline on smoking cessation. Portugal centre for evidence based medicine university of Lisbon school of medicine, Medicine. 2008.

van Schayck OC, Pinnock H, Ostrem A, Litt J, Tomlins R, Williams S, et al. IPCRG consensus statement: tackling the smoking epidemic—practical guidance for primary care. Prim Care Respir J. 2008;17(3):185–93.

Zwar N, Richmond R, Borland R, Peters M, Litt J, Bell J, et al. Supporting smoking cessation: a guide for health professionals. Melbourne: The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners; 2011.

Leone FT, Evers-Casey S, Toll BA, Vachani A. Treatment of tobacco use in lung cancer: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;143(5 Suppl):e61S–77S.

Lingford-Hughes A, Welch S, Peters L, Nutt D. BAP updated guidelines: evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological management of substance abuse, harmful use, addiction and comorbidity: recommendations from BAP. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26(7):899–952.

Chan K, Chandler J, Cheong K, Giam PE, Kanagalingam D, Lee LL, et al. Health promotion board-ministry of health clinical practice guidelines: treating tobacco use and dependence. Singapore Med J. 2013;54(7):411–5.

WHO. WHO recommendations for the prevention and management of tobacco use and second-hand smoke exposure in pregnancy. Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2013.

MoHM Disease Control Division. Clinical practice guidelines on treatment of tobacco use disorder. Malaysia: Tobacco Control Unit & FCTC Secretariat, Non-Communicable Disease Section; 2016.

Tønnesen P, Carrozzi L, Fagerström KO, Gratziou C, Jimenez-Ruiz C, Nardini S, et al. Smoking cessation in patients with respiratory diseases: a high priority, integral component of therapy. Eur Respir J. 2007;29(2):390–417.

Kelly Mike, Morgan Antony, Owen Lesley, Jones Dylan, Peploe Karen, Doohan Emma, et al. Smoking: stopping in pregnancy and after childbirth. United Kingdom: NICE; 2018.

JCS Joint Working Group. Guidelines for smoking cessation (JCS 2010)-digest version. Circ J. 2012;76(4):1024–43.

Kelly Mike, Younger Tricia, Ellis Simon, Shearn Pete, Killoran Amanda, Sheppard Linda, et al. Smoking: acute, maternity and mental health services. United Kingdom: NICE; 2013.

McRobbie H, Baiabe H, Barlow D, Beverley K, Bullen DC, Eadie S, et al. Background and recommendations of the New Zealand guidelines for helping people to stop smoking. New Zealand: Ministry of Health; 2014.

National Center for Smoking Cessation and Training. Local stop smoking services: services and delivery guidance 2014. England: National center for smoking cessation and training; 2014.

Al-Katheeri HA, Alfehaidi AS, Siddig IO, Garcia MB, AlHuneiti RAS, Jaran M. Clinical guidelines for the state of Qatar: management of tobacco dependency. Qatar: Ministry of Public Health; 2016.

Shields PG, Herbst RS, Arenberg D, Benowitz NL, Bierut L, Luckart JB. Smoking cessation. USA: National comprehensive cancer network; 2017.

Van Schayck OCP, Williams S, Barchilon V, Baxter N, Jawad M, Katsaounou PA, et al. Treating tobacco dependence: guidance for primary care on life-saving interventions. Position statement of the IPCRG. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2017;27(1):38.

Hopkins S, Macleod J, McDaid D, Lines S, Chapman R, Milne R, et al. Stop Smoking cervices. England: NICE; 2018.

Weel Cv, Bladeren FAv, Coebergh JWW, Drenthen AJM, Kaandorp CJE, Schippers GM, et al. Guideline: Treatment of tobacco dependence. Netherlands: The programme evidence-based guideline development of the Dutch society of medical specialists, Dutch institute for healthcare. 2006.

Selby P, Bean T, Els C, Ferrence R, Garcia J, McDonald P, et al. Canadian smoking cessation clinical practice guideline. Canada: Can-Adapt; 2012.

van Zyl-Smit RN, Allwood B, Stickells D, Symons G, Abdool-Gaffar S, Murphy K, et al. South African tobacco smoking cessation clinical practice guideline. 2013;103(11):869–76.

Batra A, Petersen KU, Hoch E, Andreas S, Bartsch G, Gohlke H, et al. S3 guideline: screening, siagnostics, and treatment of harmful and addictive tobacco use”. SUCHT. 2016;62(3):139–52.

Siu AL. Behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(8):622–34.

Fiore M, Jaén CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Bennett G, Benowitz NL, et al. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. A U.S. public health service report. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(2):158–76.

World Health Organization. Tobacco key facts USA: World Health Organization. 2019 [updated 26 July 2019; cited 2019 1 Nov 2019]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco.

Molino C, Leite-Santos NC, Gabriel FC, Wainberg SK, Vasconcelos LP, Mantovani-Silva RA, et al. Factors associated with high-quality guidelines for the pharmacologic management of chronic diseases in primary care: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(4):553–60.

Farghali AA, Al-Khawaja R, Madi L, Elbardissy A, Hamdy HM, Wilby KJ. Rigorous method to assess quality and generalizability of clinical practice guidelines. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2014;67(5):397–8.

Uzeloto JS, Moseley AM, Elkins MR, Franco MR, Pinto RZ, Freire A, et al. The quality of clinical practice guidelines for chronic respiratory diseases and the reliability of the AGREE II: an observational study. Int J Physiother. 2017;103(4):439–45.

Shiffman RN, Shekelle P, Overhage JM, Slutsky J, Grimshaw J, Deshpande AM. Standardized reporting of clinical practice guidelines: a proposal from the conference on guideline standardization. 2003;139(6):493–8.

Grol R, Cluzeau FA, Burgers JS. Clinical practice guidelines: towards better quality guidelines and increased international collaboration. 2003;89(Suppl 1):S4–8.

Gagliardi AR, Brouwers MC. Do guidelines offer implementation advice to target users? A systematic review of guideline applicability. 2015;5(2):e007047.

Mirzaei M, Aspin C, Essue B, Jeon YH, Dugdale P, Usherwood T, et al. A patient-centred approach to health service delivery: improving health outcomes for people with chronic illness. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:251.

Acknowledgments

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library.

Funding

This work was supported by a student grant (QUST-1-CPH-2018-13) from Qatar University Office of Research and Graduate Studies. (email: VPRGS.OFFICE@qu.edu.qa). The content of the paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Qatar University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

El Hajj, M.S., Jaam, M., Sheikh Ali, S.A.S. et al. Critical appraisal of tobacco dependence treatment guidelines. Int J Clin Pharm 43, 85–100 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-020-01110-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-020-01110-4