Abstract

Background Especially in elderly with polypharmacy, medication can do harm. Clinical pharmacists integrated in primary care teams might improve quality of pharmaceutical care. Objective To assess the effect of non-dispensing clinical pharmacists integrated in primary care teams on general practitioners’ prescribing quality. Setting This study was conducted in 25 primary care practices in the Netherlands. Methods Non-randomised, controlled, multi-centre, complex intervention study with pre-post comparison. First, we identified potential prescribing quality indicators from the literature and assessed their feasibility, validity, acceptability, reliability and sensitivity to change. Also, an expert panel assessed the indicators’ health impact. Next, using the final set of indicators, we measured the quality of prescribing in practices where non-dispensing pharmacists were integrated in the team (intervention group) compared to usual care (two control groups). Data were extracted anonymously from the healthcare records. Comparisons were made using mixed models correcting for potential confounders. Main outcome measure Quality of prescribing, measured with prescribing quality indicators. Results Of 388 eligible indicators reported in the literature we selected 8. In addition, two more indicators relevant for Dutch general practice were formulated by an expert panel. Scores on all 10 indicators improved in the intervention group after introduction of the non-dispensing pharmacist. However, when compared to control groups, prescribing quality improved solely on the indicator measuring monitoring of the renal function in patients using antihypertensive medication: relative risk of a monitored renal function in the intervention group compared to usual care: 1.03 (95% CI 1.01–1.05, p-value 0.010) and compared to usual care plus: 1.04 (1.01–1.06, p-value 0.004). Conclusion This study did not demonstrate a consistent effect of the introduction of non-dispensing clinical pharmacists in the primary care team on the quality of physician’s prescribing.

This study is part of the POINT-study, which was registered at The Netherlands National Trial Register with trial registration number NTR‐4389.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impacts on Practice

-

Prescribing indicators might not capture the full effect of non-dispensing pharmacists integrated in primary care teams, when interventions are not specifically targeted upon these indicators.

-

A non-dispensing pharmacist integrated in the primary care team improves the monitoring of renal function in patients using diuretics, compared to usual care.

-

Future studies on complex, generic interventions should use a mixed methods design to evaluate the effects on quality of care.

Background

To prevent medication-related harm in the expanding group of elderly with polypharmacy [1, 2], various innovations in the organisation of pharmaceutical care are currently implemented. Integration of clinical pharmacists in primary care teams potentially improves the quality and safety of pharmacotherapy and is currently being evaluated in various formats in Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom and Ireland [3,4,5,6]. Also in the Netherlands a non-dispensing clinical pharmacist (NDP), providing patient-centred pharmaceutical care in close collaboration with the general practitioner (GP), was recently introduced [7].

Clinical pharmacy services provided by such pharmacists in primary care can be either disease-specific, tailored to a patient population with a specific medical condition; or patient-centred, when provided to a more heterogeneous patient population, such as patients with polypharmacy, patients prescribed at least one medication or patients at risk of medication problems [8].

So far, largest impact of this new care model was found when pharmacists were fully integrated into primary care teams, providing multifaceted interventions and follow up to patients, and with the possibility of face-to-face communication between pharmacist and GP [9, 10]. Effects are mainly found on reducing drug therapy problems and improving proxy outcomes (such as blood pressure control or decreasing HbA1c levels). Yet, effects on prescription quality indicators, commonly used for quality monitoring on practice level by regulators and insurers, is scarce.

Aim of the study

Despite the promising results, integration of pharmacists in primary care teams has not been adopted widely yet. In this study, we evaluated the effect of patient-centred care delivered by NDPs integrated in primary care teams on medication safety on a practice level. Hereto, we compared NDP-led care with usual care on prescription outcomes, as indicator of quality of pharmaceutical patient care [11].

Methods

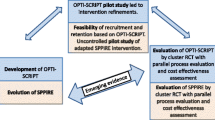

This study was part of the Pharmacotherapy Optimisation through Integration of a Non-dispensing pharmacist in primary care Teams (POINT) study [7]: a non-randomised, controlled intervention study, comparing NDP-led care (intervention group) with two current models of pharmaceutical care (control groups).

The integration of an NDP in primary care teams should be considered as a complex intervention, as it comprises of different interacting components, targets multiple levels of organisation, has variable outcomes and needs to be tailored to the context in which it is implemented [12, 13]. Hence, its evaluation should be multidimensional, including a theoretical framework underlying the expected intervention effect, and assessment of feasibility, effectiveness and related process changes. The theoretical framework as well as results on feasibility and effectiveness have been described elsewhere [14,15,16]; in the present study we focus on the process changes as measured with indicators that can be derived from computerised healthcare records.

Ethics approval

The POINT protocol was reviewed by the Medical Ethical Committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht and was deemed not eligible for full assessment (METC protocol number 13-432C). Patient data were extracted anonymously, according to data protection regulations.

Intervention and control groups

For the POINT study, ten (PharmD) pharmacists were trained as NDPs in a 15-months training program [17]. These NDPs were attached to general practices, collaborating closely with the GPs while being fully integrated in the team. Their key activities were both on a patient level, providing clinical medication reviews and patient consultations for medication problems, as well as on a practice level, educating staff and implementing quality improvement projects. For these quality improvement projects, the NDPs were allowed to select different topics, tailored to the needs of the practice. The NDPs mainly focussed on care for elderly with polypharmacy, but provided pharmaceutical care for younger patients or those with less medications as well (especially in improvement projects). Their role was allowed to evolve during the trial and, if needed, to be adjusted to the needs of daily practice. Most NDPs were relatively at the beginning of their career, with working experience varying from less than 1 year (n = 3), 1–3 years (n = 5) and between 5 and 10 years (n = 2); mainly in community pharmacies (n = 9). The NDPs were blinded for outcome measures (except for the primary outcome: medication-related hospital admissions) during the study period.

Intervention group practices were included only when they were explicitly willing to host an NDP, as willingness of all participating parties to improve pharmaceutical patient care has been recognised as a key condition for successfully implementing an NDP in primary care [3].

Two control groups consisted of the “usual care group”, in which pharmaceutical care was provided by local community pharmacists, and the “usual care plus group”, in which community pharmacists had an additional training [18, 19] in performing clinical medication reviews. Control group practices were matched to the practices in the intervention group as much as possible, with regard to practice size, degree of urbanisation, socioeconomic status and patients’ age distribution. Full details of the design of the POINT-study have been described elsewhere [7].

Setting and patients

This study was performed in all 25 general practices that participated in the POINT-study. Patients registered in one of these practices, aged 50 years or older and using at least one type of chronic medication (defined as having 3 or more prescriptions per year of the same ATC-3-level medication) were included.

Study period

We did a pre-post comparison, comparing the prescribing quality during 2013 (pre period) with the prescribing quality in the intervention year, starting June 1st 2014 until May 31st 2015 (post period). The NDPs worked full time in the practices during the intervention year.

Outcome: quality of prescribing

To evaluate the GPs’ prescribing quality, we used process indicators, as these have been reported most sensitive to differences in quality of care: they are easier to interpret than outcome indicators, and are usually more sensitive to small differences [20].

Selection of indicators

We collected indicators from literature and policy documents. Indicators were assessed step-wise, including assessment of feasibility, validity, acceptability, reliability and sensitivity to change (Box 1) [11] and health impact. Additional indicators were formulated if needed. For details of the selection procedure, see Online Supplement 1.

Data collection

We used anonymised healthcare data routinely extracted from the GPs’ electronic medical records. These data comprised of basic patient characteristics, such as sex and age, and contained all prescribed medications, registered comorbidities and lab tests performed during the study periods. We also collected data on the five months prior to both periods, as for some indicators a timeframe of more than one year was required.

Sample size calculation

No separate sample size calculation was performed. Data were considered a secondary outcome measurement of the POINT-study, for which a sample size calculation on the primary outcome (medication-related hospitalisations) was performed [7]. Outcomes on the primary outcome have been described elsewhere [16].

Analysis

Scores on indicators are reported as percentages. Differences in scores over time were reported per study group, but as practices were not randomised, those differences should not be formally compared. Hence, performance per indicator was compared between study groups using mixed models. For a detailed description of the mixed models, see Online Supplement 2. The Consort-checklist for non-randomised trials was used for writing the manuscript (see Online Supplement 3) [21].

Results

Indicators of prescribing quality

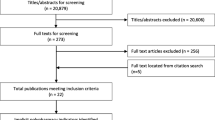

The PubMed-search yielded 42 articles, of which 16 were considered relevant. From these, 318 indicators were included. From professional and policy literature we collected an additional 141 indicators. After removing duplicates, 388 indicators remained for assessment, resulting in 8 eligible indicators (see Fig. 1). Of those, two concerned long-term medication use. Because of the nature of our intervention, we needed to alter the definition of ‘long-term’ used in these two indicators in order to enable the indicators to adequately capture change in prescribing quality.

Two additional indicators were formulated by the expert panel. The ten final indicators are summed in Box 2.

Participating practices

One NDP stopped during the study period, so we evaluated prescribing quality of 9 practices in the intervention group. In the control groups, for the usual care group 10 practices and for the usual care plus group 6 practices were included. Intervention and control practices were comparable with respect to practice characteristics and patient demographics, except for practice size (see Table 1).

Fidelity of the intervention

All NDPs implemented quality improvement projects in their practices, but content and scheduling of these projects varied: some projects were implemented right after the NDPs started working in the practice, but others were (partly) implemented only two months before the intervention period ended. This may have limited their effect. The number of projects per practice ranged from 1 to 14 (median 10). Box 3 gives an overview of the covered topics. Six topics matched with clinical themes of the final indicator set.

Quality of prescribing

In the intervention group, all indicators of desirable prescribing improved, while those measuring undesirable prescribing decreased (Table 2). In the control groups comparable trends were seen, but not for all indicators (for details, see Online Supplement 4).

After correction for potential confounders and taking the baseline differences into account in mixed models, 4 out of 10 indicators differed between intervention and control group (Table 3, and described in detail in Online Supplement 4).

Discussion

We assessed the effect of NDPs integrated in primary care teams on the quality of GP prescribing, using 10 selected indicators of prescribing quality. Although the scores of all quality indicators improved in the intervention group, and not in the control groups, we could not demonstrate a consistent favourable effect of NDP introduction on prescribing quality after correction for baseline differences and potential confounders.

Comparison with existing literature

To our knowledge, only few studies have used process indicators to assess effects of integrating an NDP in primary care teams. In Canada, the effect of integrating a team of a pharmacist and nurse practitioners in primary care was measured using indicators on quality of care for chronic disease management [26]. Most of these indicators concerned prescribing (for example: recommended aspirin in patients with coronary artery disease), but some regarded physical examinations (for example: feet examination in patients with diabetes). Comparable to our study, all indicators improved over time after introduction of the intervention, when examined within the intervention group alone (except for two indicators in which performance was considered relatively high already at baseline). In contrast to our study, the performance of the intervention group was subsequently compared to a control group using a composite indicator. This showed a result in favour of the intervention group. We did not use a composite indicator, as a composite is very dependent on the way it is constructed: differently constructed composite scores can even result into different conclusions being drawn about quality, especially when they include a wide range of medical conditions, different numbers of indicators triggered by a patient and when they include both frequently and more rarely triggered indicators [27].

In a United Kingdom-based study, the effect of a pharmacist-led information technology intervention in primary care on prescribing quality was assessed [28]. In comparison to a control group receiving only simple feedback, significant differences in favour of the intervention group for seven of the 12 measured indicators were found. This result may be explained by the fact that the pharmacist-led information technology intervention was specifically targeted on the measured indicators, while in our study NDP-led care was mainly broadly implemented: focussing on specific interventions can increase the potential to detect change. Although the quality improvement projects implemented by the NDPs were targeted at specific patients groups, the variation in projects among practices was still substantial (see Table 2). Although this variation was explicitly allowed, the resulting heterogeneity and dilution may explain the absence of a consistent effect on the prescribing quality indicators.

Interpretation of results

We did not find a consistent effect of the integration of NDPs in primary care teams on prescription indicators. Although prescription indicators are considered a suitable measurement for medication safety effects, they may be too specific to assess the true effect of a heterogeneous intervention such as patient-centred NDP-led care.

Still, we found some specific effects that resulted from the NDP intervention: in practices with an integrated NDP, the renal function was monitored more frequently in patients using antihypertensives, compared to in usual care practices. We think this is a result from the clinical medication reviews performed by NDPs, as renal function monitoring was not frequently part of the quality improvement projects. This finding adds to the evidence that the quality of clinical pharmacy services improves when the pharmacist is embedded in clinical practice: NDPs are fully integrated in primary care teams, whilst community pharmacists operate separately from general practice teams. This is also illustrated by a previous finding that recommendations given by NDPs were more frequently followed by GPs, compared to recommendations by community pharmacists [29].

In contrast, we found that in the intervention group patients with a history of cardiovascular disease were prescribed NSAIDs more often as compared to control groups. As almost all NDPs had the use of NSAIDs in CVD patients incorporated in their quality improvement projects (n = 8), this does appear as an unexpected negative outcome. However, we suggest this may be related to the composition of the indicator: whilst quality improvement projects were implemented during the intervention year, the indicator measured NSAID-use with a single prescription at any time in the intervention year. Hence, it could be that the indicator underestimated the intervention effect, as changes following interventions in patients after a first prescription were not captured by the indicator anymore.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths. We thoroughly assessed a broad selection of indicators, in order to achieve a reliable set to measure the effect of a non-dispensing pharmacist in primary care teams on GPs’ prescribing. Furthermore, the intervention was multifaceted and tailored to the practice and patients’ needs, in a real-world clinical environment. Including patients on a practice level might increase generalisability of results.

Some limitations need to be taken into account as well. First of all, the fact that we—deliberately—chose not to randomise participating practices, may have biased the comparison between the study groups. We corrected for this using mixed models, adjusting for potential relevant baseline characteristics, however bias can’t be fully ruled out.

Second, two limitations concern the use of indicators to measure quality. These limitations are in fact characteristics of indicators that are important to be aware of when interpreting data on indicators, and hence are more a general constraint of using indicators as outcome measurement rather than a specific limitation of this study. First, an indicator can measure only a part of the care provided; it will never reflect the total quality of care. By selecting a set of indicators, we tried to gain a wider insight into the quality of prescribing during the provision of NDP-led pharmaceutical care; however, it is still possible that pharmaceutical care improved despite the fact that we couldn’t measure it. Second, evidence based practice requires personalised decisions, sometimes deviating from guidelines. Therefore, optimal prescription outcomes for individual patients may not be optimally reflected in mean indicator scores: “the higher (or the lower) score the better” may not be the aim for every individual [30].

Last, limitations concerning the use of routine healthcare data need to be discussed. First, routine healthcare data are registered for healthcare use, not for research purposes. If data are not registered by GPs, they cannot be measured when using routine healthcare data [31]. Hence, they may reflect quality of registration more than quality of care provided. Second, as data of all patients registered in the practice are extracted, the problem of missing values arises as patients can ‘enter’ the dataset when newly registering and ‘leave’ the dataset when deregistering. Overall, mixed models can handle missing data quite well, but this might still influence our findings. In line with this limitation is the problem of populations changing over time, which changes the case mix of practices. If characteristics of this case mix are related to the indicator, this might influence indicator findings. We tried to exclude such influence as much as possible during the assessment of indicators, however it might still be present to some extent [32]. Another problem of using data of all patients registered in the practice is that a final intervention effect might be diluted: in the intervention group, we could not distinguish patients who had received an NDP-led intervention from patients who had no NDP-led intervention. Especially our choice to include a rather broad patient population (aged 50 years and older, using one or more chronic medications) might add to this potential dilution phenomenon. However, as we wanted to measure the complete intervention effect, we preferred this broader patient population over a more detailed population such as patients aged 65 years and older, with polypharmacy), even though the latter may reduce the dilution problem.

So, using extensive data sets such as routinely collected healthcare data is not without limitations. We tried to counter these limitations by applying the same method in each study group and selecting indicators that are least susceptible to misinterpretation. However, we believe interpreting findings based on indicators measured in routine registry data remains uncertain. As a consequence, one should be aware of the above mentioned constraints that might put findings and comparisons at risk.

Implications for practice

This sub study, focused on measuring the impact of an NDP integrated in primary care with currently used quality indicators, showed no consistent effect of the intervention. Whether this indicates that the NDP does not adequately target the main prescribing problems in GP practice, or that the quality indicators used did not capture the NDP’s effectiveness around these problems remains unsolved. Taking results from the other sub studies of the POINT project into account [16, 29, 33], the latter option may be plausible as our intervention should be considered as complex [13, 34].

Conclusion

We assessed the effect of NDPs integrated in primary care teams on the quality of prescribing by GPs, using a compiled set of indicators. Although scores on all prescribing quality indicators improved after introduction of the NDP, we could not demonstrate a consistent improvement in prescribing quality in comparison with usual pharmaceutical care. To evaluate such a complex intervention however, in addition to measuring effects on quality, the “how” and “why” of (absence) of effects needs to be addressed as well to fully understand these results.

Abbreviations

- GP:

-

General practitioner

- NDP:

-

Non-dispensing pharmacist

- POINT:

-

Pharmacotherapy optimisation through integrating a non-dispensing pharmacist in primary care teams

References

Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, Green C, Scott AK, Walley TJ, et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. BMJ. 2004;329:15–9.

Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error: the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139.

Dolovich L, Pottie K, Kaczorowski J, Farrell B, Austin Z, Rodriguez C, et al. Integrating family medicine and pharmacy to advance primary care therapeutics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83(6):913–7.

Jameson JP, VanNoord GR. Pharmacotherapy consultation on polypharmacy patients in ambulatory care. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35:835–40.

Tan E, Stewart K, Elliott RA, George J. An exploration of the role of pharmacists within general practice clinics: the protocol for the pharmacists in practice study (PIPS). BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:246.

Cardwell K, Clyne B, Moriarty F, Wallace E, Fahey T, Boland F, et al. Supporting prescribing in Irish primary care: protocol for a non-randomised pilot study of a general practice pharmacist (GPP) intervention to optimise prescribing in primary care. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2018;4:122.

Hazen ACM, Sloeserwij VM, Zwart DLM, de Bont AA, Bouvy ML, de Gier JJ, et al. Design of the POINT study: pharmacotherapy Optimisation through integration of a non-dispensing pharmacist in a primary care team (POINT). BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:76.

Stewart M. Towards a global definition of patient centred care. BMJ. 2001;322:444–5.

Tan ECK, Stewart K, Elliott RA, George J. Pharmacist services provided in general practice clinics: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2014;10:608–22.

Hazen AC, de Bont AA, Boelman L, Zwart DL, de Gier JJ, de Wit NJ, et al. The degree of integration of non-dispensing pharmacists in primary care practice and the impact on health outcomes: a systematic review. Res Soc Adv Pharm. 2018;14:228–40.

Campbell S, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, Marshall M. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11:358–64.

Datta J, Petticrew M. Challenges to evaluating complex interventions: a content analysis of published papers. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:568.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655.

Hazen ACM, de Bont AA, Leendertse AJ, Zwart DLM, de Wit NJ, de Gier JJ, et al. How clinical integration of pharmacists in general practice has impact on medication therapy management: a theory-oriented evaluation. Int J Integr Care. 2019;19(1):1–8.

Hazen ACM, van der Wal AW, Sloeserwij VM, Zwart DLM, de Gier JJ, de Wit NJ, et al. Controversy and consensus on a clinical pharmacist in primary care in the Netherlands. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38:1250–60.

Sloeserwij VM, Hazen ACM, Zwart DLM, Leendertse AJ, Poldervaart JM, de Bont AA, et al. Effects of non-dispensing pharmacists integrated in general practice on medication-related hospitalisations. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85(10):2321–31.

Hazen A, de Groot E, de Gier H, Damoiseaux R, Zwart D, Leendertse A. Design of a 15-month interprofessional workplace learning program to expand the added value of clinical pharmacists in primary care. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2018;10:618–26.

PAO Farmacie. Periodieke Individuele Analyse Farmacotherapie (PIAF)-opleiding; 2011. https://www.paofarmacie.nl/uploads/files/folder_PIAF_def.pdf. Accessed 29 April 2020.

KNMP. Service Apotheek Farmacotherapie Expert (SAFE)-opleiding; 2016. https://www.pe-online.org/public/opleidingdetail.aspx?pid=131&courseID=236420&button=close. Accessed 29 April 2020.

Mant J. Process versus outcome indicators in the assessment of quality of health care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2001;13(6):475–80.

Reeves BC, Gaus W. Guidelines for reporting non-randomised Studies. Forsch Komplement Klass Nat. 2004;11:46–52.

CBS. StatLine. https://statline.cbs.nl/statweb/?LA=nl. Accessed 12 Oct 2018.

Knol F. Statusontwikkeling van wijken in Nederland 1998–2010. Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau; 2012. https://www.scp.nl/Publicaties/Alle_publicaties/Publicaties_2012/Statusontwikkeling_van_wijken_in_Nederland_1998_2010. Accessed 12 Oct 2018.

Carey IM, Shah SM, Harris T, DeWilde S, Cook DG. A new simple primary care morbidity score predicted mortality and better explains between practice variations than the Charlson index. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:436–44.

RIVM. Chronische ziekten en multimorbiditeit. https://www.volksgezondheidenzorg.info/onderwerp/chronische-ziekten-en-multimorbiditeit/cijfers-context/prevalentie#bron--node-nivel-zorgregistraties-eerste-lijn-chronicshe-ziekten-en-multimorbiditeit. Accessed 12 Oct 2018.

Hogg W, Lemelin J, Dahrouge S, Liddy C, Armstrong CD, Legault F, et al. Randomized controlled trial of anticipatory and preventive multidisciplinary team care. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:e76–85.

Reeves D, Campbell SM, Adams J, Shekelle PG, Kontopantelis E, Roland MO. Combining multiple indicators of clinical quality: an evaluation of different analytic approaches. Med Care. 2007;45(6):489–96.

Avery AJ, Rodgers S, Cantrill JA, Armstrong S, Cresswell K, Eden M, et al. A pharmacist-led information technology intervention for medication errors (PINCER): a multicentre, cluster randomised, controlled trial and cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet. 2012;379:1310–9.

Hazen ACM, Zwart DLM, Poldervaart JM, de Gier JJ, de Wit NJ, de Bont AA, et al. Non-dispensing pharmacists’ actions and solutions of drug therapy problems among elderly polypharmacy patients in primary care. Fam Pract. 2019;36(5):544–51.

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Gray JAM, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t; it’s about integrating individual clinical expertise and the best external evidence. BMJ. 1996;312:71–2.

Sollie A, Roskam J, Sijmons RH, Numans ME, Helsper CW. Do GPS know their patients with cancer? Assessing the quality of cancer registration in Dutch primary care: a cross-sectional validation study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e012669.

Teichert M, Schoenmakers T, Kylstra N, Mosk B, Bouvy ML, van de Vaart F, et al. Quality indicators for pharmaceutical care: a comprehensive set with national scores for Dutch community pharmacies. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38:870–9.

Hazen ACM, de Groot E, de Bont AA, de Vocht S, de Gier JJ, Bouvy ML, et al. Learning through boundary crossing: professional identity formation of pharmacists transitioning to general practice in the Netherlands. Acad Med. 2018;93(10):1531–8.

Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: medical research council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:h1258.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ellen Kaan, Mirjam Medendorp-Hempenius, Zacharias de Waal, Peter Zuithoff and all 25 practices that participated in the POINT-study for their contributions.

Funding

A research grant was obtained from the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (Grant Agreement Number 80-833600-98-10206). Implementation of NDPs was financed by an unconditional grant of the Foundation Achmea Healthcare, a Dutch health insurance company (Project Number Z456). Both study sponsors had no role in the design of the study, nor in the data collection, analyses, interpretation of the data and in the writing of the report or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sloeserwij, V.M., Zwart, D.L.M., Hazen, A.C.M. et al. Non-dispensing pharmacist integrated in the primary care team: effect on the quality of physician’s prescribing, a non-randomised comparative study. Int J Clin Pharm 42, 1293–1303 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-020-01075-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-020-01075-4