Abstract

Background Community pharmacies are promising locations for opportunistic screening due to pharmacist accessibility and ability to perform various health and medication management services. Little is known as to the provision of pharmacy services following screening initiatives. Objective To describe provision of pharmacy services for participants following a community pharmacy stroke screening initiative. Setting The Program for the Identification of “Actionable Atrial” Fibrillation Pharmacy initiative took place in 30 pharmacies in Alberta and Ontario, Canada. 1149 participants ≥ 65 were screened for atrial fibrillation, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension. Method Retrospective, secondary analysis of data using participant case-report forms, pharmacy data, and pharmacy claims to describe pharmacy services received by participants post-screening. Main Outcome Measure Number and types of remunerated pharmacy services received by participants post-screening. Results A total of 535/1149 (46.6%) participants screened at their regular pharmacy were included in this analysis. Of these, 165 (30.8%) participants received 229 pharmacy services within 3 months post-screening, including 146 medication reviews, 57 influenza vaccinations, and 21 pharmaceutical opinions. A median (interquartile range, IQR) of 6 (2–11) pharmacy services were delivered, and median (IQR) reimbursement was $187.50 ($67.50–$342.50). Conclusions Approximately one-third of participants received a pharmacy service within 3 months post-screening. Relatively large numbers of annual and follow-up medication reviews were delivered despite low eligibility for annual-only reviews and despite many missed opportunities for pharmacy service provision in at-risk patients. In-pharmacy screening may facilitate provision of some services, namely medication reviews, by providing opportunities to identify patients at-risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impacts on practice

-

In-pharmacy screening initiatives represent an opportunity for patient follow-up, which may include provision of remunerated pharmacy services.

-

The most frequently provided services post screening in Canada are medication reviews, influenza vaccinations and pharmaceutical opinions.

-

Despite low eligibility for annual reviews, high numbers of both annual and follow-up medication reviews are provided after in-pharmacy screening initiative.

-

Participants in a pharmacy screening program may be willing to attend CVD or diabetes screening sessions in locations other than their home pharmacy.

Introduction

Within Canada and around the world, pharmacist practice is shifting away from dispensing activities and towards a patient-centred model of care [1,2,3,4,5]. Community pharmacists are increasingly focusing on medication management services, including medication reviews, prescription adaptation and extension, smoking cessation consultations, and independent prescribing [6,7,8,9]. These services are useful for identifying medication-related problems, and for ongoing patient monitoring and follow-up, especially where chronic disease is present.

In addition to medication management services, other activities such as community pharmacy-based opportunistic screening for chronic and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors, are gaining popularity. Opportunistic screening, defined as screening that is “carried out at a time when people are seen, by health care professionals, for a reason other than the disorder in question”, is cost-effective, can help detect and prevent chronic disease, and can be effective at reducing morbidity [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Screening for CVD, diabetes and stroke risk factors in community pharmacies offers the possibility of linking people with newly-identified potential health risks to an on-site pharmacist. Pharmacists can provide guidance on screening results, help navigate the healthcare system (including encouraging patients to speak with their family physician), and provide recommendations and services to improve medication management. Community pharmacists thus have an emerging role in CVD, diabetes and stroke prevention and management, augmented by their accessibility and role as experts in the safe and effective use of medications [9]. However, it is imperative that follow-up care is appropriate and high-quality [16, 22, 23].

Few studies have investigated how remunerated pharmacy services are provided following community pharmacy screening initiatives for CVD, stroke prevention or diabetes. Many screening initiatives defer patient follow-up to physicians, or have pharmacists provide patient education post-screening; very few discuss use of formal, remunerated services such as medication reviews. Furthermore, most pharmacy screening initiatives include patient counselling or education, rather than exploring their use as part of usual practice after the activity is complete. This study investigated the use of remunerated pharmacy services following an in-pharmacy initiative, the Program for Identification of “Actionable” Atrial Fibrillation pharmacy study (PIAAF), that provided opportunistic screening and risk assessment for atrial fibrillation (AF), hypertension and type 2 diabetes to community-dwelling individuals. Combining AF screening for stroke prevention with assessment for other health risks provided an opportunity to identify those who could benefit the most from focused attention, including those with more than one health issue.

Aim of study

The objective of this secondary analysis, the PIAAF-professional pharmacy service analysis (PIAAF-PPS), was to describe the extent (number, type, remuneration) of remunerated service delivery post-PIAAF screening in two Canadian provinces, Ontario and Alberta. These jurisdictions are reported separately due to differences in available remunerated services between provinces (Tables 2 and 3). It was hypothesized that in both jurisdictions, the PIAAF initiative would encourage more services to be provided to study participants. This study sought to provide a better real-world understanding of gaps and continuity of care between screening initiatives and pharmacist services. Most research deals with these two activities separately or as part of very structured research protocols (i.e. randomized controlled trials).

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board. A formal data sharing agreement between McMaster University and Rexall pharmacies was in place to allow sharing of pharmacy records with the study team (with participant consent). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Methods

PIAAF pharmacy

The PIAAF study was an organized, community pharmacy-based initiative to screen community-dwelling elders for AF and hypertension, and assess risk for type 2 diabetes [23, 24]. Approximately 1175 seniors (> 65 years) from Hamilton, Ontario, and Edmonton, Alberta attended screening/assessment sessions in 30 Rexall chain pharmacies between October 2014 and April 2015. AF was screened using a single-lead, handheld electrocardiogram (ECG), diabetes risk was assessed using the CANRISK tool [25], and blood pressure (BP) was measured using the PharmaSmart in-pharmacy kiosk [26]. Participants screening positive for AF were recommended to receive a 12-lead ECG, either through their family physician or an AF clinic. Results for participants at risk for any factor were sent to their family physician. Community pharmacists were not formally referred to counsel individuals identified at-risk, however, participants were encouraged to speak to the pharmacist about their results. The intention was to mimic usual practice in pharmacies where screening opportunities are provided (such as through BP kiosks) without a mandatory pharmacist appointment.

Participants and pharmacies

PIAAF participants who reported that the pharmacy where they were screened/assessed was also their primary or “home” pharmacy were included in this analysis. Participants with a different home pharmacy were also included if a partial pharmacy profile was located, or if they received a pharmacy service at the pharmacy where they were screened. Pharmacies were included if data extraction was possible, and if > 1 eligible participant received screening/assessment at that location.

Data sources

Data were collected from two sources: case report forms (CRFs) for each participant, collected at the time of assessment; and pharmacy profile and administrative billing data.

Data extracted from CRFs included: (1) name and date of birth; (2) pharmacy where screening/assessment was performed, and whether this was their home pharmacy; (3) date of screening/assessment; (4) self-reported medication use; (5) self-reported medical conditions; (6) BP measurements; (7) AF screening results; (8) CANRISK assessment results in those < 74 years without known diabetes; and (9) smoking status.

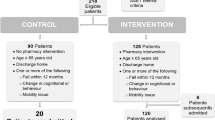

Where participant pharmacy profiles (either full or partial) were located at the screening/assessment pharmacy, the following data were extracted: (1) audit histories for all product or drug information numbers (PINS/DINS) billed from October 1, 2014 to October 31, 2015 including fill date, quantity authorized and dispensed, and status (e.g. completed, cancelled); (2) any chronic conditions/diagnoses listed. This was used to calculate number of medications taken, and identify new or potentially inappropriate medications dispensed (assessed using the Beers List criteria) [27]. Of 1149 enrolled PIAAF study participants, 614 (53.4%) were excluded from the PIAAF-PPS analysis because screening sessions were not held at their home pharmacy (n = 575), or because profiles were inactivated (e.g. following death or admission into long-term care) or otherwise unable to be located (e.g. due to incorrectly transcribed data on CRFs) (n = 39). Partial profiles for 45 participants were found. Therefore, 535 (46.6%) PIAAF participants from 26 pharmacies were included. Demographic information, including self-reported medication use, was collected for all 535 participants. Pharmacy claims data was considered the ‘gold standard’; however, some claims data could not be retrieved, or was incomplete. In these cases, self-reported data from CRFs was used to impute number of medications (n = 44).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed for the mean number of pharmacy services provided within 3 months of screening, per participant; median number of services provided, per region and pharmacy; median dollar amount reimbursed for services, per region and pharmacy; and counts of each type of pharmacy service provided on the day of assessment, within the first week, and within 3 months of assessment, per region and pharmacy. Both provinces were compared to investigate whether the difference in available remunerated services impacted pharmacy service delivery. Only the dollar amounts reimbursed to pharmacies for remunerated services were reported, as pharmacies did not incur any cost of intervention. An economic analysis of the PIAAF Pharmacy screening initiative (i.e. not taking into account pharmacy services) has been reported elsewhere [24]. Chi square tests were performed to investigate whether there were significant differences in patient demographics and medication use between jurisdictions. Analyses were performed using SPSS v23.

Results

Of the 535 participants included in this analysis, 404 (76%) were from Ontario, and 131 (24%) were from Alberta. Figure 1 demonstrates the flow of participants from the PIAAF study through the PIAAF-PPS analysis.

Of 30 participating pharmacies, 26 (87%) were included. One pharmacy closed following PIAAF, and one did not utilize Rexall’s proprietary software system (thus, data could not be extracted). The remaining two did not enroll any regular customers; no pharmacy services were linked to participants assessed at those stores.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics for PIAAF-PPS participants are reported in Table 1. The mean age (SD) was 75.4 (6.8), and 56% were female. History of hypertension was reported in 299 (56%) participants, known diabetes was reported in 120 (22.4%), and 8 (1.5%) reported pre-diagnosed AF. Only 32 (6.0%) were smokers.

Pharmacy services

165 participants received 229 pharmacy services within 3 months post-screening. These included: 145 medication reviews [71 (49%) annual-only, 74 (51%) follow-ups], 57 influenza vaccinations, 21 pharmaceutical options (Ontario), 4 assessments for prescription renewals (Alberta), 1 assessment for prescription adaptation (Alberta), and 1 smoking cessation consultation (Ontario). Participants received an average (SD) of 0.43 (0.76) pharmacy services, with an average (SD) of 1.43 (0.73) in those receiving > 1 service. There was a large variation in the number of pharmacy services provided per pharmacy, ranging from 0 to 45 with a median (IQR) of 6 (2–11). 351 (67%) participants had received any remunerated service in the year prior to screening/assessment, and 194 (36%) participants were (or became) eligible for an annual-only review during the post-screening initiative period. Of these 194 eligible participants, 71 (37%) received an annual-only medication review during this timeframe. In total, 66 services were provided on the date of screening/assessment, of which 35 (53%) were medication reviews.

The median dollar amount (IQR) reimbursed per pharmacy for remunerated services was $187.50 ($67.50–$342.50).Footnote 1 In total, participating pharmacies were reimbursed $7,877.50 for pharmacy services billed for participants within 3 months of screening/assessment. Stores in Ontario tended to provide more services, especially on the day of screening. Stores in Alberta provided a larger proportion of medication reviews compared to Ontario.

Ontario

During the 3 month post-screening initiative period, 127 (31%) Ontario participants received 167 pharmacy services: 98 (59%) medication reviews, 47 (28%) influenza vaccinations, 21 (13%) pharmaceutical opinions, and 1 (0.6%) smoking cessation consultation (Table 2). 128 (32%) participants were eligible for annual-only medication reviews: 57 (58%) of the identified medication reviews received were annual-only and 41 (42%) were follow-ups. The number of services provided per pharmacy ranged from 1 to 45, with a median (IQR) of 8 (4–14). 51 participants (40%) received 54 services (32%) on the day of the screening, 14 participants (11%) received 14 services (8%) in the first week post-screening, and 81 (64%) participants received 99 services (59%) during the remaining 3-month period. The total dollar value reimbursed per pharmacy for remunerated services ranged from $60.00 to $1780.00, with a median (IQR) per pharmacy of $263.75 ($120.00–$347.50).

Alberta

During the 3 month post-screening initiative period, 38 (29.0%) Alberta participants received 62 pharmacy services: 47 (75.8%) medication reviews, 10 (16.1%) influenza vaccinations, 4 (6.5%) assessments for prescription renewal, and 1 (1.6%) assessment for prescription adaptation. 66 (50%) participants were eligible for an annual-only medication review: 14 (30%) of the identified medication reviews were annual-only, and 33 (70%) were follow-ups (Table 3). The number of services provided per pharmacy ranged from 0 to 20, with a median (IQR) of 4.5 (1–6). 19.4% (12/62) of services occurred on the same day as screening. 11 participants (29%) received 12 services (19%) on the day of screening/assessment, 4 participants (11%) received 4 services (6%) in the first week post-screening, and 30 (79%) participants received 46 services (74%) during the remaining 3-month period. The dollar amount reimbursed per pharmacy for remunerated services ranged from $0.00 to $970.00, with a median (IQR) of $132.50 ($22.50–$232.50).

Screening results

Results for > 1 screening test were missing from 16 (3%) CRFs. 15 (2.8%) participants screened positive for AF. Of these, Sandhu et al. [23] reported that 9 spoke to the pharmacist after screening, and 9 had OAC subsequently prescribed by a specialist or family physician. 529 (99%) participants screened had a CHA2DS2-VASc score of > 1, indicating a low-to-moderate risk of stroke [28]. 160 (30%) participants had raised BP at the time of screening, including 54 (10.3%) participants with known diabetes. Mean (SD) BP was 139.7/75.6 mmHg (21.2/12.1 mmHg). 203 participants < 74 years were risk-assessed for diabetes using the CANRISK questionnaire: 99 (48.8%) were at high risk, and 88 (43.3%) were at intermediate risk. Assessment results are presented in Table 4.

Medication use

Participants took a mean (SD) of 4.4 (3.3) medications, ranging from 0 to 19. Polypharmacy was identified in 237 (48%) participants (defined here as use of > 4 concurrent medications). The most commonly used medications were statins (50%), and low-dose ASA (54%). Medication use per jurisdiction (self-reported and from pharmacy claims data) is reported in supplemental Table 1.

Discussion

Approximately one-third of PIAAF participants received at least one remunerated service within 3 months post-screening initiative. Most billed pharmacy services were medication reviews, accounting for approximately two-thirds of identified services. Other services (e.g. prescription adaptation, pharmaceutical opinions, and smoking cessation consultations) were far less frequent. Participant screening/assessment represented an opportunity for subsequent pharmacist intervention; this study shows that provision of pharmacy services to PIAAF participants generated just under $7, 880.00 of revenue for participating pharmacies. This number could have been higher had all PIAAF participants at risk for stroke, diabetes or CVD received a medication review; therefore, not all opportunities for patient follow-up were capitalized upon. Had all PIAAF participants (not just those included in this analysis) screening positive for AF, at high- or intermediate-risk for diabetes, with history of hypertension, or with high BP at time of screening received a medication review (annual or follow-up, based on eligibility), the total dollar amount reimbursed across all participating pharmacies would have been approximately $33,000.00 (calculated using pricing for non-APA SMMAs in Alberta). Nevertheless, many PIAAF participants received a medication review on the same day of screening/assessment, demonstrating that in-pharmacy screening/assessment and provision of pharmacy services can be successfully combined, especially when screening sessions are planned ahead of time, as was the case with the PIAAF program. Although influenza vaccinations were the second-most common service provided, uptake remained low. This may be due to the fact that approximately half of the screening sessions were not held during the annual flu-shot season (roughly October–December). Previous research has also shown that older adults are more likely to receive flu shots at their physician’s office [29].

Many PIAAF participants were found to be at risk for stroke, diabetes, hypertension, or a combination of these. The number of participants screening positive for AF was comparable to a population prevalence of approximately 3–5% in those > 65 (US data) [30]. Almost all participants were found to have moderate risk of stroke or higher [23]. The majority assessed with CANRISK were found to be at high or intermediate risk of diabetes. This was on top of those with known diabetes, a rate which was consistent with a reported prevalence of approximately 16–25% in Canadians aged > 65 [31]. The prevalence of hypertension was also consistent with Canadian averages (roughly 60%) [32]; just under a third of participants had raised BP at the time of screening. Some of these participants may have benefitted from additional BP control. Despite a comparatively low average number of medications [6, 33], polypharmacy was present in almost half of participants. Altogether, this represents a large proportion of participants that may have benefited from pharmacist-delivered monitoring and follow-up services like medication reviews (including MedsCheck diabetes and diabetes-focused SMMAs), pharmaceutical opinions (in Ontario) or prescriptive authority (in Alberta).

Some pharmacies were reimbursed more for providing less, but more intensive, time-consuming services (e.g. medication reviews) than pharmacies that performed more, but quicker, less complex services (e.g. influenza vaccinations). This was especially true in Alberta, where the vast majority of provided services were medication reviews. Considering that approximately one-third of participants were eligible for an annual medication review during the post-screening period, the number of medication reviews provided was high; in fact, just over half of identified reviews were follow-ups. Pharmacists likely feel there is a trade-off between time spent performing pharmacy services and reimbursement [34]. Low smoking cessation consultation rates in both provinces were likely related to the very low smoking rate observed in this cohort compared to the Canadian rate of 18.1% [35], but may also be due to low implementation of these services in community pharmacies, as has been seen in Ontario [36].

This study had several limitations. Because participant pharmacy data could only be extracted for participants who attended screening sessions at their home pharmacy, over half of PIAAF participants were excluded. This reduced the available sample size and the number of identified pharmacy services. The fact that over half of PIAAF participants were not screened in their home pharmacy may suggest that many people were interested enough in their screening/assessment results that they were willing to participate outside of their regular health care setting. Pharmacies in Ontario recruited more regular pharmacy patrons than in Alberta and provided more services; two Alberta sites provided no pharmacy services for PIAAF participants, and two provided one service each. This disparity demonstrates that while pharmacy service provision is possible within certain pharmacy workflows, it was not widespread or consistent even within one pharmacy organization. This study also does not consider services that were recommended but not accepted. There was no comparison group to allow comparisons between people who did and did not participate in the screening initiative. Strengths of this study include a large number of participating pharmacies and a relatively large number of eligible participants, even after exclusions were made. To our knowledge, this is the first Canadian study investigating use of pharmacy services in everyday practice following a three-pronged screening and assessment initiative. Screening initiatives such as PIAAF may have some potential to increase the provision of pharmacy services for those at risk, while also bolstering pharmacy revenue via remuneration for these services. Further research, including analyses of larger administrative datasets that can link routinely collected data from screening initiatives with reimbursed pharmacy services or pragmatic randomized controlled trials, would be necessary to substantiate these findings.

Conclusions

Approximately one-third of participants attending a community pharmacy screening initiative for AF, hypertension and diabetes received at least one remunerated pharmacy service within 3 months. Medication reviews were the most frequently provided service, followed by influenza vaccinations, and pharmaceutical opinions. A relatively high number of eligible participants received an annual-only review, and a large number of follow-up reviews were also identified. With the exception of influenza vaccinations, most services were provided more than 1 week post-screening; however, many medication reviews were also performed on the day of screening. While there was considerable inter-pharmacy variation in the number of post-screening services provided, this study shows that pharmacies could potentially receive large amounts of reimbursement for providing remunerated services to participants screening at risk. However, many potentially useful services (e.g. prescribing interventions) were underutilized, indicating that a greater opportunity for the provision of services exists than was capitalized upon. Pharmacy service provision following in-pharmacy screening could potentially be augmented by direct pharmacist involvement in screening, e.g. by entering screening results into patient profiles. Overall, this study provides some evidence that community pharmacy screening sessions may help facilitate provision of remunerated services, especially medication reviews.

Notes

All dollar amounts are reported in CAD.

References

Canadian Pharmacists Association. Pharmacy in Canada. 2016. http://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/pharmacy-in-canada/Pharmacy%20in%20Canada.pdf. Accessed 22 Mar 2018.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A Program guide for public health: partnering with pharmacists in the prevention and control of chronic diseases. US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta. 2012. www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/programs/nhdsp_program/resources.htm. Accessed 5 Jan 2018.

Pharmaceutical Society of New Zealand. New Zealand national pharmacist services framework. Pharmaceutical Society of New Zealand Incorporated, Wellington. 2014. https://www.psnz.org.nz/Folder?Action=View%20File&Folder_id=86&File=PSNZPharmacistServicesFramework2014FINAL.pdf. Accessed 5 Jan 2018.

Moles RJ. Pharmacy practice in Australia. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2015;68(5):418–26.

Smith J, Picton C, Dayan M. The nuffield trust. Now more than ever: why pharmacy needs to act. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2014. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/files/2017-01/now-more-than-ever-web-final.pdf. Accessed 5 Jan 2018.

Dolovich L, Consiglio G, MacKeigan L, Abrahamyan L, Pechlivanoglou P, Rac V, et al. Uptake of the medscheck annual medication review service in Ontario community pharmacies between 2007 and 2013. Can Pharm J. 2016;149:293–302.

Fish A, Watson M, Bond C. Practice-based pharmaceutical services: a systematic review. IJPP. 2002;10:225–33.

Kelly D, Young S, Phillips L, Clark D. Patient attitudes regarding the role of the pharmacist and interest in expanded pharmacy services. Can Pharm J. 2014;147:239–47.

Touchette D, Doloresco F, Suda K, Perez A, Turner S, Jalundhwala Y, et al. Economic evaluations of clinical pharmacy services:2006–2010. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:771–93.

World Health Organization. Screening for type 2 diabetes: report of a World Health Organization and International Diabetes Federation meeting. WHO, Geneva. 2003. www.who.int/diabetes/publications/en/screening_mnc03.pdf. Accessed 5 Jan 2018.

Moran PS, Flattery MJ, Teljeur C, Ryan M, Smith SM. Effectiveness of systematic screening for the detection of atrial fibrillation. Cochrane DB Syst Rev. 2013;30(4):CD009586.

Hobbes F, Fitzmaurice D, Mant J, Murray E, Jowett S, Bryan S, et al. A randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness study of systematic screening (targeted and total population screening) versus routine practice for the detection of atrial fibrillation in people aged 65 and over. The SAFE study. Health Technol Assess. 2005;9(iii-iv, ix-x):1–74.

Kahn R, Alperin P, Eddy D, Borch-Johnsen K, Buse J, Feigelman J, et al. Age at initiation and frequency of screening to detect type 2 diabetes: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:1365.

Hoerger T, Harris R, Hicks K, Donahue K, Sorenson S, Engelgau M. Screening for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:689.

Gillies C, Lambert P, Abrams K, Sutton A, Cooper N, Hsu R, et al. Different strategies for screening and prevention of type 2 diabetes in adults: cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ. 2008;336:110.

Adler A, Prabhakaran D, Bovet P, Kazi D, Mancia G, Mungal-Singh V, et al. Reducing cardiovascular mortality through prevention and management of raised blood pressure a world heart federation roadmap. Glob Heart. 2015;10:111–22.

Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration, Turnbull F, Neal B, Ninomiya T, Algert C, Arima H, Barzi F, et al. Effects of different regimens to lower blood pressure on major cardiovascular events in older and younger adults: meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2008;336:1121.

Basile J, Bloch M. Overview of hypertension in adults. UpToDate. 2016. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-hypertension-in-adults. Accessed 22 Mar 2018.

Kuipersmith J, Holmes-Rovner M, Hogan A, Rovner D, Gardiner J. Cost-effectiveness analysis in heart disease, part II: preventative therapies. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1995;37:243–71.

Kaczorowski J, Chambers L, Dolovich L, Paterson J, Karwalajtys T, Gierman T, et al. Improving cardiovascular health at population level: 39 community cluster randomised trial of cardiovascular health awareness program (CHAP). BMJ. 2011;2011(342):d442.

World Health Organization. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases: 2013–2020. WHO, Geneva. 2013. www.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/94384/1/9789241506236_eng.pdf. Accessed 5 Jan 2018.

McCulloch D, Hayward R. Screening for type 2 diabetes mellitus. UpToDate. 2016. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/screening-for-type-2-diabetes-mellitus?source=search_result&search=diabetes%20mellitus%20type%202&selectedTitle=8~150. Accessed 22 Mar 2018.

Sandhu R, Dolovich L, Deif B, Barake W, Agarwal G, Grindvalds A, et al. High prevalence of modifiable stroke risk factors identified in a pharmacy-based screening program. Open Heart. 2016;3:e000515. https://doi.org/10.1136/openhrt-2016-000515.

Tarride JE, Dolovich L, Blackhouse G, Guertin J, Burke N, Manja V, et al. Screening for atrial fibrillation in Canadian pharmacies: an economic evaluation. CMAJ Open. 2017;5(3):E653–61.

Kaczorowski J, Robsinson C, Nerenberg K. Development of the CANRISK questionnaire to screen for prediabetes and undiagnosed type 2 diabetes. Can J Diabetes. 2009;33:3881–85.

Alpert BS. Validation of the pharma-smart PS-2000 public use blood pressure monitor. Blood Press Monit. 2004;9:19–23.

American Geriatric Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;2015(63):2227–46.

Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJ. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137(2):263–72.

Ontario Pharmacy Research Collaboration. Wins & needles: how pharmacists give influenza vaccination a shot in the arm. http://www.open-pharmacy-research.ca/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/wins-and-needles.pdf. Accessed 12 Feb 2018.

Feinberg W, Blackshear J, Laupacis A, Kronmal R, Hart RG. Prevalence, age distribution and gender of patients with atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:469–73.

Public Health Agency of Canada. Diabetes in Canada: facts and figures from a public health perspective. PHAC, Ottawa. 2011. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/cd-mc/publications/diabetes-diabete/facts-figures-faits-chiffres-2011/chap1-eng.php. Accessed 6 Jan 2018.

Robitaille C, Dai S, Waters C, Loukine L, Bancej C, Quach S, et al. Diagnosed hypertension in Canada: incidence, prevalence and associated mortality. CMAJ. 2012;184:E49–56.

Pechlivanoglou P, Abrahamyan L, MacKeigan L, Consiglio G, Dolovich L, Li P, et al. Factors affecting the delivery of community pharmacist-led medication reviews: evidence from the MedsCheck Annual service in Ontario. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:666.

Bradley F, Wagner AC, Elvey R, Noyce P, Ashcroft D. Determinants of the uptake of medicines use reviews (MURs) by community pharmacies in England: a multi-method study. Health Policy. 2008;88:258–68.

Statistics Canada. Smokers, by sex, provinces and territories (percent). 2016. Retrieved from: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/health74b-eng.htm. Accessed 28 Feb 2018.

Wong L, Burden A, Liu Y, Tadrous M, Pojskic N, Dolovich L, et al. Initial uptake of the Ontario pharmacy smoking cessation program. Can Pharm J. 2015;148:29–40.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to all who made this research possible, including Dr. Sherilyn Houle who served as external examiner on KL’s MSc thesis committee, Alex Grinvalds who coordinated data extraction at the Public Health Research Institute, Vanessa Prescott, Jennifer Lamch, Aaron Schrama, Vu Nguyen, and Mona Sabharwal who helped with project coordination and data extraction at Rexall Canada. The authors would also like to acknowledge April Chan for her help with preparing the study data, and Anita DiLoreto for her help with preparing the final manuscript for submission.

Funding

This work was supported by the Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal, as a pilot project under the Canadian Chronic Disease Awareness and Management Project, Grant Number 2000472.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lancaster, K., Thabane, L., Tarride, JE. et al. Descriptive analysis of pharmacy services provided after community pharmacy screening. Int J Clin Pharm 40, 1577–1586 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-018-0742-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-018-0742-5