Abstract

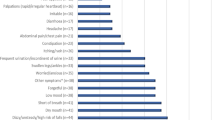

Background Medication assessment tools (MATs) may be implemented in routine electronic data sources in order to identify patients with opportunities for optimisation of medication therapy management (MTM) and follow-up by a multi-disciplinary team. Objective (1) To demonstrate the use of a MAT for cardiovascular conditions (MATCVC) as a means of profiling potential opportunities for MTM optimisation in primary care and (2) to assess the performance of MATCVC in identifying actual opportunities for better care. Setting Members of a pharmacotherapy discussion group, i.e. two single-handed general practitioners (GPs), three GP partners, and community pharmacists (CPs) from each of two community pharmacies, in a rural part of the Netherlands. Methods MATCVC comprises 21 medication assessment criteria, each of which is designed to detect a specific care issue and to check whether it is ‘addressed’ by provision of guideline recommended care or ‘open’ in the presence (‘open explained’) or absence (‘open unexplained’) of pre-specified explanations for guideline deviations. (1) Relevant data was extracted from linked GP and CP electronic records and MATCVC assessment was conducted to profile the population of CVC patients registered with both, participating CPs and GPs, in terms of ‘open unexplained’ care issues. (2) A purposive sample of patients with ‘open unexplained’ care issues was reviewed by each patient’s GP. Main outcome measures Number and proportion of ‘open unexplained’ care issues per MATCVC criterion and per patient. The number of patients with MATCVC detected ‘open unexplained’ care issues to be reviewed (NNR) in order to identify one that requires changes in MTM. Results In 1,876 target group patients, MATCVC identified 6,915 care issues, of which 2,770 (40.1 %) were ‘open unexplained’. At population level, ten MATCVC criteria had particularly high potential for quality improvement. At patient level, 1,277 (68.1 %) target group patients had at least one ‘open unexplained’ care issue. For patients with four or more ‘open unexplained’ care issues, the NNR was 2 (95 % CI 2–2). Conclusion The study demonstrates potential ways of using MATCVC as a key component of a collaborative MTM system. Strategies that promote documentation and sharing of explanations for deviating from guideline recommendations may enhance the utility of the approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- ACEI:

-

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor

- AF:

-

Atrial fibrillation

- ARB:

-

Angiotensin receptor blocker

- BB:

-

Beta blocker

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- CCB:

-

Calcium channel blocker

- CE:

-

Clinical explanation

- CHADS2 :

-

Stroke risk stratification tool in atrial fibrillation, where congestive heart failure, hypertension, age >75 and diabetes mellitus score 1 point each and a history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack score 2 points. A score of 0 is deemed ‘low’, a score of 1 ‘intermediate’ and a score of ≥2 ‘high’ risk

- CHD:

-

Coronary heart disease

- CHF:

-

Chronic heart failure

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CP:

-

Community pharmacist

- CVC:

-

Cardiovascular condition

- CVD:

-

Vascular disease comprising peripheral vascular disease, history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack and coronary heart disease or history of acute coronary syndrome

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- GP:

-

General practitioner

- HbA1c:

-

Glycosylated haemoglobin

- HTN:

-

Hypertension

- ICPC:

-

International classification of primary care

- MAT:

-

Medication assessment tool

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- MTM:

-

Medication therapy management

- NNR:

-

Number needed to review

- OAC:

-

Oral anticoagulant

- PAD:

-

Peripheral vascular disease

- RASI:

-

Renin angiotensin system inhibitor

- TIA:

-

Transient ischaemic attack

References

Pratt N, Roughead EE, Ryan P, Gilbert AL. Differential impact of NSAIDs on rate of adverse events that require hospitalization in high-risk and general veteran populations: a retrospective cohort study. Drugs Aging. 2010;27(1):63–71.

European Society of Cardiology. ESC Guidelines on the management of stable angina pectoris. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(11):1341–81.

European Society of Cardiology. ESC guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eu J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14(Suppl 2):S1–113.

European Society of Cardiology. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;28:1598–660.

European Society of Cardiology. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10(10):933–89.

European Society of Cardiology. ESC guidelines on the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(23):2909–45.

European Society of Cardiology. ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2010;12(10):1360–420.

Steinman MA. Polypharmacy and the balance of medication benefits and risks. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5(4):314–5.

Cribb A, Barber N. Prescribers, patients and policy: the limits of technique. Health Care Anal. 1997;5(4):292–8.

Barber N. What constitutes good prescribing? BMJ. 1995;310:923–5.

Erhardt LR. Barriers to effective implementation of guideline recommendations. Am J Med. 2005;118(Suppl 12):36–41.

Wolf-Maier K, Cooper RS, Banegas JR, Giampaoli S, Hense H, Joffres M, et al. Hypertension prevalence and blood pressure levels in 6 European countries, Canada and the United States. JAMA. 2003;289:2363–9.

Ogilvie IM, Newton N, Welner S. Underuse of oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2010;123:638–45.

Nieuwlaat R, Capucci A, Lip GYH, Olsson SB, Prins MH, Nieman FH, et al. Antithrombotic treatment in real-life atrial fibrillation patients: a report from the Euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(24):3018–26.

Safford M, Shewchuk R, Qu H. Reasons for not intensifying medications: differentiating “clinical inertia” from appropriate care. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1648–55.

Epping-Jordan JE, Pruitt SD, Bengoa R, Wagner EH. Improving the quality of health care for chronic conditions. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:299–305.

Gotsman I, Rubonivich S, Azaz-Livshits T. Use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers in patients with congestive heart failure: an observational study of treatment rates and clinical outcome. Israel Med Assoc J (IMAJ). 2008;10(3):214–8.

Wagner EH. The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management. BMJ. 2000;320:569–72.

Blenkinsopp A, Bond CM. The potential and pitfalls of medicine management: what have we learned so far? Dis Manag Health Outcomes. 2008;16(2):79–86.

McConnell KJ, Denham AM, Olson KL. Pharmacist-led interventions for the management of cardiovascular disease: opportunities and obstacles. Dis Manag Health Outcomes. 2008;16(3):131–44.

Kocken G. Pharmacotherapy discussion groups in the Netherlands under the spotlight. 1998 [cited 27 Feb 2013]. Available from http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Jwhozip10e/11.html#Jwhozip10e.11.1.

VanMil JWF. Pharmaceutical care in community pharmacy: practice and research in the Netherlands. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:1720–5.

Bouvy M, Dessing R, Duchateau F. White paper on pharmacy in the Netherlands. Position on pharmacy, pharmacists and pharmacy practice. Royal Dutch Pharmacists Association. 2011 [cited 27 Feb 2013]. Available from: http://www.knmp.nl/downloads/over-de-knmp/knmp-vereniging/Witboek_eng.pdf.

Bond C. The MEDMAN study: a randomized controlled trial of community pharmacy-led medicines management for patients with coronary heart disease. Fam Pract. 2007;24(2):189–200.

Leendertse AJ. Hospital admissions related to medication—prevalence, provocation and prevention. PhD thesis. 2010.

RESPECT trial team. Effectiveness of shared pharmaceutical care for older patients: rESPECT trial findings. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;59:14–20.

Beers MH. Explicit criteria for determining potentially inappropriate medication use by the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1531–6.

O’Mahony D, Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, Hamilton H, Barry P, et al. STOPP & START criteria: a new approach to detecting potentially inappropriate prescribing in old age. Eur Geriatr Med. 2010;1(1):45–51.

Garcia BH, Utnes J, Naalsund LU, Giverhaug T. MAT-CHDSP, a novel medication assessment tool for evaluation of secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(3):249–57.

Kamyar M, Johnson BJ, McAnaw JJ, Lemmens-Gruber R, Hudson SA. Adherence to clinical guidelines in the prevention of coronary heart disease in type II diabetes mellitus. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30(1):120–7.

Ernst A, Kinnear M, Hudson S. Quality of prescribing: a study of guideline adherence of medication in patients with diabetes mellitus. Pract Diabetes Int. 2005;22(8):285–90.

Hakonsen GD, Hudson S, Loennechen T. Design and validation of a medication assessment tool for cancer pain management. Pharm World Sci. 2006;28(6):342–51.

Hakonsen GD, Strelec P, Campbell D, Hudson S, Loennechen T. Adherence to medication guideline criteria in cancer pain management. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2009;37(6):1006–18.

Garcia B, Småbrekke L, Trovik T, Giverhaug T. Application of the MAT-CHDSP to assess guideline adherence and therapy goal achievement in secondary prevention of coronary heart disease after percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(3):703–9. doi:10.1007/s00228-012-1402-7.

Diab MI, Johnson BJ, Hudson SA. Adherence to clinical guidelines in management of diabetes and prevention of cardiovascular disease in Qatar. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012;. doi:10.1007/s11096-012-9714-3.

Dreischulte T, Grant A, McCowan C, McAnaw J, Guthrie B. Quality and safety of medication use in primary care: consensus validation of a new set of explicit medication assessment criteria and prioritisation of topics for improvement. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 2012;12(1):5.

Altman DG. Confidence intervals for the number needed to treat. BMJ. 1998;317:1309.

Rahimtoola H, Timmers A, Dessing R, Hudson S. An evaluation of community pharmacy records in the development of pharmaceutical care in The Netherlands. Pharm World Sci. 1997;19(2):105–13.

Westert GP, Schellevis FG, de Bakker DH, Groenewegen PP, Bensing JM, van der Zee J. Monitoring health inequalities through general practice: the second Dutch national survey of general practice. Eur J Pub Health. 2005;15(1):59–65.

Mosterd A, Hoes AW, de Bruyne MC, Deckers JW, Linker DT, Hofman A, et al. Prevalence of heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction in the general population; The Rotterdam Study. Eur Heart J. 1999;20(6):447–55.

Merry AH, Boer JA, Schouten L, Feskens EM, Verschuren WMM, Gorgels AM, et al. Validity of coronary heart diseases and heart failure based on hospital discharge and mortality data in the Netherlands using the cardiovascular registry Maastricht cohort study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24(5):237–47.

NHS Scotland. Chronic medication service [cited 27 Feb 2013]. Available from http://www.communitypharmacy.scot.nhs.uk/core_services/cms.html.

Hysong JS, Best RG, Pugh JA. Audit and feedback and clinical practice guideline adherence: making feedback actionable. Implement Sci. 2006;1:9.

Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380(9836):37–43.

Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Samsa GP, Weinberger M, Uttech KM, Lewis IK, et al. A method for assessing drug therapy appropriateness. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(10):1045–51.

Howard R, Avery A, Bissell P. Causes of preventable drug-related hospital admissions: a qualitative study. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;17:109–16.

Machado M, Bajcar J, Guzzo GC, Einarson TR, Machado M, Bajcar J, et al. Sensitivity of patient outcomes to pharmacist interventions. Part II: systematic review and meta-analysis in hypertension management. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(11):1770–81.

Machado M, Bajcar J, Guzzo GC, Einarson TR, Machado M, Bajcar J, et al. Sensitivity of patient outcomes to pharmacist interventions. Part I: systematic review and meta-analysis in diabetes management. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(10):1569–82.

Machado M, Nassor N, Bajcar JM, Guzzo GC, Einarson TR, Machado M, et al. Sensitivity of patient outcomes to pharmacist interventions. Part III: systematic review and meta-analysis in hyperlipidemia management. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(9):1195–207.

van den Berg N, Fiss T, Meinke C, Heymann R, Scriba S, Hoffmann W. GP-support by means of AGnES-practice assistants and the use of telecare devices in a sparsely populated region in Northern Germany—proof of concept. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10:44. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-10-44.

Bradley F, Ashcroft DM, Noyce PR. Integration and differentiation: a conceptual model of general practitioner and community pharmacist collaboration. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2012;8(1):36–46.

Holland R, Desborough J, Goodyer L, Hall S, Wright D, Loke YK. Does pharmacist-led medication review help to reduce hospital admissions and deaths in older people? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;65(3):303–16.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all general practitioners and community pharmacy staff, who participated in this study. This study would not have been possible without Professor Steve Hudson, who sadly passed away during the preparation of this paper.

Funding

The study was conducted without specific external funding. During the conduct of this study, T.D. was supported by personal grants from the Harold and Marjorie Charitable Trust, Dr. Anni and Dr. August Lesmueller Stiftung and the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Steve Hudson: Deceased.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dreischulte, T., Johnson, J., McAnaw, J. et al. Medication assessment tool to detect care issues from routine data: a pilot study in primary care. Int J Clin Pharm 35, 1063–1074 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-013-9828-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-013-9828-2