Abstract

Objective Heart failure patients are regularly admitted to hospital and frequently use multiple medication. Besides intentional changes in pharmacotherapy, unintentional changes may occur during hospitalisation. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of a clinical pharmacist discharge service on medication discrepancies and prescription errors in patients with heart failure. Setting A general teaching hospital in Tilburg, the Netherlands. Method An open randomized intervention study was performed comparing an intervention group, with a control group receiving regular care by doctors and nurses. The clinical pharmacist discharge service consisted of review of discharge medication, communicating prescribing errors with the cardiologist, giving patients information, preparation of a written overview of the discharge medication and communication to both the community pharmacist and the general practitioner about this medication. Within 6 weeks after discharge all patients were routinely scheduled to visit the outpatient clinic and medication discrepancies were measured. Main outcome measure The primary endpoint was the frequency of prescription errors in the discharge medication and medication discrepancies after discharge combined. Results Forty-four patients were included in the control group and 41 in the intervention group. Sixty-eight percent of patients in the control group had at least one discrepancy or prescription error against 39% in the intervention group (RR 0.57 (95% CI 0.37–0.88)). The percentage of medications with a discrepancy or prescription error in the control group was 14.6% and in the intervention group it was 6.1% (RR 0.42 (95% CI 0.27–0.66)). Conclusion This clinical pharmacist discharge service significantly reduces the risk of discrepancies and prescription errors in medication of patients with heart failure in the 1st month after discharge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impact of findings on practice

-

The studied clinical pharmacist discharge service reduces the percentage of heart failure patients with one or more discrepancies or prescription errors by almost a half (68% vs. 39%).

-

The information about medication at discharge for heart failure patients needs to be optimized for community pharmacists, for general practitioners, and for the patients.

Introduction

Heart failure is a chronic, progressive disease characterized by frequent hospital admissions and high mortality rates [1]. The primary goals of improving disease management in patients with heart failure are optimization of the pharmacological therapy and improving adherence to medication and lifestyle. Medication such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and β-blockers are well established in the treatment of heart failure, reducing mortality and readmissions [2]. Despite pharmacotherapy, outcomes for patients remain poor and frequent hospitalisations remain necessary [3]. Hospital admissions usually lead to changes in medication use. Most changes are intended, for example adjusting dosage during hospital admission. Other changes, however, are unintended as is the case with prescription errors. In addition, medication discrepancies after hospital discharge can occur by insufficient patient education or insufficient communication to the general practitioner (GP) or the patient his community pharmacist about the intentional changes [4]. A possible consequence of these discrepancies and prescription errors can be readmission [3].

A recent review demonstrated that pharmacist care in the treatment of heart failure greatly reduces the risk of all-cause and heart failure hospitalization, particularly if the pharmacist was a member of a multidisciplinary team [5]. Yu et al. have systematically compared the disease management programmes for older patients with heart failure. This review showed that a program must be multifaceted and should consist of an in-hospital phase of care, intensive patient education, exercise and psychosocial counselling, self care supportive strategy, optimization of medical regimen, and ongoing surveillance and management of clinical deterioration [6]. There is also evidence that a pharmacist intervention for outpatients with heart failure can improve adherence to cardiovascular medications and decrease health care cost [7]. However, the study of Holland et al. [8] did not find a reduction in hospital admissions when a community pharmacist led the intervention in contrast to the results found when a specialist nurse led the intervention. These studies all looked at readmission and hospitalization. None of the studies have focused on the reduction of medication discrepancies after hospital discharge, which may be an indicator of readmission.

Several studies have been published which describe methods to optimize medication use after hospital discharge, but the most effective method has not been established yet [9–11]. A possible useful strategy is providing patients with more information about the (side)effects of their medication and explaining the changes made in pharmacotherapy during their admission. Al-Rashed et al. [10] showed that pharmaceutical counselling before discharge, together with a medication and information discharge summary and a medicine reminder chart lead to better drug knowledge and compliance and a reduction of readmissions. Providing the patient with a copy of the drugs prescribed on discharge, i.e. a full overview of the current medication which can be incorporated into the patient his medication record at the community pharmacy, also seems to be effective. Discharging 19 patients with such information to take to their community pharmacist could result in the prevention of one unintentional discrepancy having a definite adverse effect [11].

Research on the prevention of medication discrepancies has mainly taken place in the USA and UK. Within these countries the availability of hospital pharmacists is higher than within the countries of the European continent. This makes extrapolation of the results to the European situation difficult and projects can not be easily implemented in European hospitals because of this manpower problem. Several solutions are possible for the manpower problem. First of all, the use of alternative personnel may be an option as was shown in two Dutch studies on medication reconciliation [12, 13]. A second solution may be to focus the attention of the clinical pharmacist on high risk patients during these interventions. Heart failure patients are such high risk patients because they use a large number of medicines and are frequently admitted to hospital [1].

Aim of the study

The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of a multifaceted clinical pharmacist discharge service on the number of medication discrepancies after discharge in heart failure patients. A secondary aim was to make an estimation of the effect of the service on non-adherence.

Method

Design

An open randomized intervention study was performed comparing an intervention group provided with the clinical pharmacist discharge service, with a control group provided with regular care by doctors and nurses.

The study protocol was approved by a medical ethics committee (Medische-Ethische Toetsing Onderzoek Patiënten en Proefpersonen, Tilburg, The Netherlands).

Setting and study population

The study was conducted at the department of cardiology of a teaching hospital in Tilburg, the Netherlands between May 2007 and July 2008.

Eligible patients were adults (aged over 18 years) admitted with a diagnosis of heart failure and prescribed five or more medicines (from any class) at discharge. We excluded patients living in a nursing home or unable to give informed consent, due to mental incapacity or terminal illness.

All patients who provided written informed consent were randomised using a random number table, to receive intervention or regular care.

Regular care

Patients in the control group received regular care, consisting of verbal and written information about their drug therapy from a nurse at hospital discharge. The discharge prescription was made by the physician and given to the patient to hand over to the GP.

Intervention

First of all, the intervention consisted of a clinical pharmacist identifying potential prescription errors in the discharge medication and discussing them with the cardiologist. This resulted in the final discharge medication. Furthermore, patients in the intervention group received verbal and written information about (side)effects of, and changes in, their in hospital drug therapy from a clinical pharmacist upon hospital discharge. In addition to this, the clinical pharmacist made a discharge medication list which contained additional information related to dose adjustments and discontinued medication. After it had been approved by the physician, the discharge medication list was faxed to the community pharmacy and given as written information to the patient with the instruction to hand it over to the GP.

All patients (both regular care and intervention) collected medication at their community pharmacy and received usual routine management by their cardiologist after discharge. This included an outpatient visit within 6 weeks after hospital discharge and an additional visit to the heart failure nurse if necessary.

Data collection

The following patient characteristics have been collected: age, sex, education (primary school or higher education), living situation (single or cohabitating), chronic co-morbidity (Chronic Disease Score, CDS [14]), routine check ups at the heart failure unit before admission, length of admission, number of medicines at discharge, living conditions after discharge (i.e. living in a nursing home, in a residential home for elderly people or at home with additional care), patient or pharmacy control over medication (i.e. patient is in control or the patient receives a “week box”, prefilled by the pharmacy; a week box contains all the medication for a week arranged by day and hour of intake) and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class upon discharge.

In addition, medication was classified by ATC code and the “source” of each drug, i.e. start or discontinuation during admission, dose adjustment or preadmission medication, was noted.

During the first follow up consultation after discharge with the cardiologist or heart failure nurse at the clinic, an estimate of adherence was made with the “Brief Medication Questionnaire—Regimen Screen” (BMQ), a validated tool for screening for adherence consisting of seven questions. This tool requires patients to list all medication taken in the past week and subsequently for each medicine listed four questions about the use of the medicine are asked, as well as three general questions about medication use. For each item patients received a score of “1” if their initial or spontaneous report indicated potential non-adherence with the current regimen for the target medication (i.e. when the specific question was answered with ‘yes’) and a score of “0” if this reports indicated no non-adherence (i.e. when the question was answered with ‘no’). The maximum score is 7 and a score of 1 or higher is an indication for potential non-adherence. Table 1 shows the questions of the BMQ [15].

In addition, the patient’s medication was checked for discrepancies and for prescription errors. Discrepancies were discussed with the patient and the cardiologist or heart failure nurse. A discrepancy was defined as a deviation in medication use compared to the medication on the discharge prescription. Discrepancies were classified as: re-start of discontinued medication, discontinuation of prescribed discharge medication, use of higher or lower dose, more or less frequent use than prescribed and incorrect time of taking medication.

A prescription error was defined as an error which occurs in the process of prescribing medication, namely dosing errors, dosage form errors, contra-indications, drug–drug interactions and double-medication. All prescription errors identified by the clinical pharmacist and agreed upon by the cardiologist were collected.

The clinical relevance of the discrepancy or prescription error was assessed by making use of the NCC MERP-index [16]. This index categorizes medication errors (class A-I), using an algorithm, see Table 2 (briefly, class A: no error, class B, C and D: error, but no harm, class E, F, G and H: error and harm, class I: error and death). Discrepancies and prescription errors in class E or higher (i.e. errors resulting in harm) are considered as clinically relevant. Three pharmacists and a cardiologist assessed the clinical relevance; for those discrepancies they disagreed on they met to reach consensus.

End points

The primary end point in this study is the total sum of the percentage of prescription errors and discrepancies after hospital discharge. The estimate of adherence as indicated by the BMQ was chosen as a secondary end point. Patients with a score of ≥1 were considered to be potentially nonadherent [15].

Data analysis

The program PS sample size (version 2.1.31) was used to determine the sample size [17]. The sample size was calculated at 62 patients per group based on α = 0.05, a power of 0.8, an estimated frequency of the end point in the control group of 30% [3, 4, 11, 18, 19] and an expected reduction to 10% [10, 20].

All data were processed in Microsoft Access 2003 and analysed with SPSS version 16.0.

The average and standard deviation were determined for continuous variables and the percentage was calculated for categorical variables. The differences between the intervention and the control group were analysed by the two sample t test for continuous variables and by the Chi-square test for categorical variables. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered to be significant.

For analysis of the primary and secondary end point the relative risk (RR) was calculated with a confidence interval (CI) of 95%. For the primary endpoint this was performed both on the medication level (number of medications as denominator) and on the patient level (% of patients with one or more discrepancy or prescription errors), and for the secondary endpoint on the patient level.

Results

We approached a total of 119 patients to participate after screening them for eligibility. The 85 patients who agreed were randomised; 44 patients in the control group and 41 patients in the intervention group (see Fig. 1). Patient characteristics are represented in Table 3. The characteristics of both groups did not differ.

Sixty-eight percent of patients in the control group had at least one discrepancy or prescription error against 39% in the intervention group (RR 0.57 (95% CI 0.37–0.88)). The percentage of medications with a discrepancy or prescription error in the control group was 14.6% and in the intervention group it was 6.1% (RR 0.42 (95% CI 0.27–0.66)) (see Table 4).

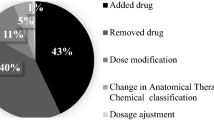

Prescription errors are most common in both groups. These are followed by re-start of discontinued medication and use of higher dose of medication in the control group. In the intervention group prescription errors are followed by discontinuation of prescribed medication and use of a lower dose of medication (see Table 5).

In the intervention group as well as the control group the highest percentage of the total number of prescription errors and discrepancies fell into class B of the NCC MERP-index (36% vs. 53%). The percentage of class E or higher was 32% in the intervention group and 29% in the control group (see Table 6).

No difference was found in the estimate of adherence between both groups: 79.5% in the control group had a BMQ score ≥ 1 (potentially non-adherent) versus 78.0% in the intervention group (RR: 1.07 (95% CI 0.47–2.44)).

Discussion

This study has investigated the effect of a discharge service by a clinical pharmacist on the occurrence of discrepancies and prescription errors in a population of heart failure patients. The percentage of patients with one or more discrepancies or prescription errors has been lowered by almost a half (68% vs. 39%).

International studies show that supervision of and providing heart failure patients with information at the time of discharge as well as postdischarge support reduces the number of readmissions and improves the patient’s quality of life [21–23]. It was not possible in this study to measure the number of readmissions caused by incorrect medicine use because it was considered unethical to leave discrepancies uncorrected during the check up at the outpatients’ clinic. However, by classifying discrepancies and prescription errors into classes of seriousness an estimate can be made of the possible consequences. The percentage of discrepancies and prescription errors in class E or higher (error and harm) is similar in both groups but the absolute numbers decrease by half in the intervention group.

The percentage of patients with at least one discrepancy or prescription errors (68% vs. 39%) was consistent with other general reports describing medication discrepancies in 14.1–59.6% of patients at discharge [4, 24–26]. Although a variety of factors contribute to the occurrence of medication discrepancies, prescribers often fail to routinely compare a patient’s inpatient medication list with his or her preadmission list at the time of prescribing and may not communicate medication information effectively at the time of discharge.

The fact that the percentage of patients who are potentially non-adherent is similar in both groups is not surprising. It is a known fact that a combination of interventions spread out over more than 3 weeks is needed to improve medication adherence [7, 27].

This study is limited in several aspects. First, medication discrepancies arising at the moment of admission were not included in the study. Results of the study by Bolas et al. [28] show that preparation of an accurate medication record at admission by a community liaison pharmacist reduces the number of these discrepancies. A combination of admission and discharge consultations could have led to a further decrease in the number of discrepancies.

Second, the interventions in this study were done by one clinical pharmacist in one hospital only, which limits the generalisability. Yet, the study is one of the few European studies that provides information on a clinical pharmacist discharge service outside the UK and the situation in this single hospital is likely to be similar to many other European hospitals with respect to the limited number of clinical pharmacists. As the study focuses on a specific high risk group, these limited resources may be used in an effective way when implementing the intervention as described in this study.

Third, less patients were included in the study than the calculated group size. Nonetheless, a statistically significant effect of the intervention could be demonstrated. The results need to be interpreted in the light that the predetermined sample size was not achieved.

Finally, the BMQ only provides an indication for potential non-adherence. Therefore it is not possible to distinguish between good or poor levels of adherence.

Strengths of the study are its randomized design and the assessment of the discrepancies by a multidisciplinary team. Other studies often solely rely on the assessment by pharmacists and they may assess the clinical relevance of discrepancies different than doctors [29].

Future studies should be performed investigating clinical pharmacist discharge services in multicenter settings, preferably using readmissions as a clinical endpoint. Such studies should also pay attention to aspects as patient satisfaction and quality of life.

Conclusion

Information about (side)effects and changes in the drug therapy given by a clinical pharmacist combined with a written overview of the discharge medication and communication to both the community pharmacist and the GP reduces discrepancies and prescription errors within a population of heart failure patients. No effect on non-adherence was found in this short follow-up study.

References

Jaarsma T, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, Sturm H, Van Veldhuisen DJ. Management of heart failure in The Netherlands. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7:371–5.

Dickstein K, Cohen-Solal A, Filippatos G, McMurray JJ, Ponikowski P, Poole-Wilson PA et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA) and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM). Eur Heart J. 2008;29(19):2388–442.

Michalsen A, Köning G, Thimme W. Preventable causative factors leading to hospital admission with decompensated heart failure. Heart. 1998;80:437–41.

Coleman EA, Smith JD, Raha D, Min SJ. Posthospital medication discrepancies, prevalence’s and contributing factors. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1842–7.

Koshman SH, Charrois TL, Simpson SH, McAlister FA, Tsuyuki RT. Pharmacist care of patients with heart failure, a systematic review of randomized trials. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(7):687–94.

Yu DSF, Thompson DR, Lee DTF. Disease management programmes for older people with heart failure: crucial characteristics which improve post-discharge outcomes. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;27:596–612.

Murray MD, Young J, Hoke S, Tu W, Weiner M, Morrow D, et al. Pharmacist intervention to improve medication adherence in heart failure, a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:714–25.

Holland R, Brooksby I, Lenaghan E, Ashton K, Hay L, Smith R, et al. Effectiveness of visits from community pharmacists for patients with heart failure: HeartMed randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007. doi:10.1136/bmj.39164.568183.AE.

Kripalani A, LeFevre F, O’Philips C, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians, Implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297:831–41.

Al-Rashed SA, Wright DJ, Roebuck N, Sunter W, Chrystyn H. The value of inpatient pharmaceutical counselling to elderly patients prior to discharge. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54:657–64.

Duggan C, Feldman R, Hough J, Bates I. Reducing adverse prescribing discrepancies following hospital discharge. Int J Pharm Pract. 1998;6:77–82.

Van den Bemt PM, van den Broek S, van Nunen AK, Harbers JB, Lenderink AW. Effect of medication reconciliation performed by pharmacy technicians on medication discrepancies at the time of pre-operative screening. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:868–74.

Karapinar-Çarkit F, Borgsteede SD, Zoer J, Smit HJ, Egberts AC, van den Bemt PM. The effect of medication reconciliation with and without patient counseling on the number of pharmaceutical interventions among patients discharged from the hospital. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:1001–10.

von Korff M, Wagner EH, Saunders K. A chronic disease score from automated pharmacy data. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(2):197–203.

Svarstad BL, Chewining BA, Sleath BL, Claesson C. The brief medication questionnaire: a tool for screening patient adherence and barriers to adherence. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;37(2):113–24.

National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NNCMERP). http://www.nccmerp.org/. Accessed 26 June 2010.

Dupont WD, Plummer WD Jr. PS power and sample size calculation. http://biostat.mc.vanderbilt.edu/twiki/bin/view/Main/PowerSampleSize. Accessed 26 June 2010.

Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, McGinn T. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:646–51.

Omori Dm, Potyk RP, Kroenke K. The adverse effects of hospitalization on drug regimens. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1562–4.

Koelling TM, Johnson ML, Cody RJ, Aaronson KD. Discharge education improves clinical outcomes in patient with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2005;111:179–85.

Phillips CO, Wright SM, Kern DE, Singa RM, Shepperd S, Rubin HR. Comprehensive discharge planning with post discharge support for older patients with congestive heart failure, a meta analysis. JAMA. 2004;291(11):1358–67.

Rainville EC. Impact of pharmacist interventions on hospital readmissions for heart failure. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56(13):1339–42.

Stewart S, Pearson S, Horowitz JD. Effects of a home-based intervention among patients with congestive heart failure discharged from acute hospital care. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(10):1067–72.

Walker PC, Bernstein SJ, Jones JN, Piersma J, Kim HW, Regal RE, et al. Impact of a pharmacist-facilitated hospital discharge program, a quasi-experimental study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):2003–10.

Wong JD, Bajcar JM, Wong GG, Alibhai SMH, Huh JH, Cesta A, et al. Medication reconciliation at hospital discharge: evaluating discrepancies. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(10):1373–9.

Vira T, Colquhuin M, Etchells E. Reconciliable differences: correcting medication errors at hospital admission and discharge. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(2):122–6.

Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X. Interventions to enhance medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008, Issue 2. Art No: CD000011. doi:1002/14651858.CD000011.pub3.

Bolas H, Brookes K, Scott M, McElnay J. Evaluation of a hospital-based community liaison pharmacy service in northern Ireland. Pharm World Sci. 2004;26:114–20.

van Doormaal JE, Mol PG, van den Bemt PM, Zaal RJ, Egberts AC, Kosterink JG, et al. Reliability of the assessment of preventable adverse drug events in daily clinical practice. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17(7):645–54.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the cardiologists, residents (heart failure) nurses and clinic assistants of the cardiac ward of the TweeSteden hospital. Also, we like to thank the residents of the hospital pharmacy Midden-Brabant for collection of data, Rob Heerdink and Toine Egberts of the University of Utrecht for calculation CDS respectively his support.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Eggink, R.N., Lenderink, A.W., Widdershoven, J.W.M.G. et al. The effect of a clinical pharmacist discharge service on medication discrepancies in patients with heart failure. Pharm World Sci 32, 759–766 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-010-9433-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-010-9433-6