Abstract

Purpose

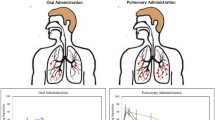

To achieve efficient antibiotic delivery to the cystic fibrosis (CF) airway using a single inhalable powder co-encapsulating a mucolytic and an antibiotic.

Methods

Inhalable dry powders containing deoxyribonuclease and/or ciprofloxacin (DNase, Cipro, and DNase/Cipro powders) were produced by spray-drying with dipalmitylphosphatidylcholine, albumin, and lactose as excipients, and their antibacterial effects were evaluated using the artificial sputum model.

Results

All powders showed mass median aerodynamic diameters below 5 µm. Both drugs were loaded in the dry powders without loss in quantity and activity. Dry powders containing DNase significantly decreased the storage modulus of the artificial sputum medium in less than 30 min. When applied to artificial sputum laden with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Cipro/DNase powder showed better antibacterial activity than Cipro powder. The higher activity of the Cipro/DNase powder is attributable to the mucolytic activity of DNase, which promotes penetration of the dry powder into the artificial sputum and efficient dissolution and diffusion of ciprofloxacin.

Conclusions

Inhalational delivery of antibiotics to the CF airway can be optimized when the sputum barrier is concomitantly addressed. Co-delivery of antibiotics and DNase using an inhalable particle system may be a promising strategy for local antipseudomonal therapy in the CF airway.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Orenstein DM, Rosenstein BJ, Stern RC. Diagnosis of Cystic Fibrosis. Cystic Fibrosis Medical Care. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2000. p. 21–53.

Genetic Testing for Cystic Fibrosis. NIH Consens Statement Online. 1997;15:1–37.

Ramsey BW. Management of pulmonary disease in patients with cystic fibrosis. New Engl J Med. 1996;335:179–88.

Murphy TM, Rosenstein BJ. Advances in the science and treatment of cystic fibrosis lung diseases: A continuing medical education resource, Duke University Medical Center & Health System, Durham, North Carolina.

Sanders NN, De Smedt SC, Van Rompaey E, Simoens P, De Baets F, Demeester J. Cystic fibrosis sputum. A barrier to the transport of nanospheres. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:1905–11.

Cotran RS, Kumar V, Collins T, Robbins SL. Robbins pathologic basis of disease. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1999.

Hodson ME, Gallagher CG, Govan JR. A randomised clinical trial of nebulised tobramycin or colistin in cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:658–64.

Hodson ME. Antibiotic treatment. Aerosol therapy. Chest. 1988;94:156S–62.

Goa KL, Lamb H. Dornase alfa. A review of pharmacoeconomic and quality-of-life aspects of its use in cystic fibrosis. Pharmacoeconomics. 1997;12:409–22.

Hodson ME, McKenzie S, Harms HK, Koch C, Mastella G, Navarro J, et al. Dornase alfa in the treatment of cystic fibrosis in Europe: a report from the Epidemiologic Registry of Cystic Fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003;36:427–32.

Garcia-Contreras L, Hickey AJ. Pharmaceutical and biotechnological aerosols for cystic fibrosis therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54:1491–504.

Parks Q, Young R, Poch K, Malcolm K, Vasil M, Nick J. Neutrophil enhancement of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development: human F-actin and DNA as targets for therapy. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58:492–502.

Vanbever R, Mintzes JD, Wang J, Nice J, Chen D, Batycky R, et al. Formulation and physical characterization of large porous particles for inhalation. Pharm Res. 1999;16:1735.

Yu X, Zipp GL, Davidson Iii GWR. The effect of temperature and pH on the solubility of quinolone compounds: estimation of heat of fusion. Pharm Res. 1994;11:522–7.

Sinicropi D, Baker DL, Prince WS, Shiffer K, Shak S. Colorimetric determination of DNase I activity with a DNA-methyl green substrate. Anal Biochem. 1994;222:351–8.

Lichtinghagen R. Determination of Pulmozyme (dornase alpha) stability using a kinetic colorimetric DNase I activity assay. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2006;63:365–8.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; Approved standard—Eighth edition (M07-A8); 2009.

Sriramulu DD, Lunsdorf H, Lam JS, Romling U. Microcolony formation: a novel biofilm model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa for the cystic fibrosis lung. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:667–76.

Shur J, Nevell TG, Ewen RJ, Price R, Smith A, Barbu E, et al. Cospray-dried unfractionated heparin with L-leucine as a dry powder inhaler mucolytic for cystic fibrosis therapy. J Pharm Sci. 2008;97:4857–68.

Chan HK, AuYeung KL, Gonda I. Effects of additives on heat denaturation of rhDNase in solutions. Pharm Res. 1996;13:756–61.

Cipolla DC, Gonda I, Meserve KC, Weck S, Shire SJ. Formulation and aerosol delivery of recombinant deoxyribonucleac-acid derived human deoxyribonuclease-I. In: Cleland JLLR (ed.) Symposium on Formulation and Delivery of Proteins and Peptides, at the 205th National Meeting of the American-Chemical-Society. Denver, Co; 1993. pp. 322–42.

Tsifansky MD, Yeo Y, Evgenov OV, Bellas E, Benjamin J, Kohane DS. Microparticles for inhalational delivery of antipseudomonal antibiotics. AAPS J. 2008;10:254–60.

Bosquillon C, Lombry C, Preat V, Vanbever R. Influence of formulation excipients and physical characteristics of inhalation dry powders on their aerosolization performance. J Control Release. 2001;70:329.

Bosquillon C, Lombry C, Preat V, Vanbever R. Comparison of particle sizing techniques in the case of inhalation dry powders. J Pharm Sci. 2001;90:2032–41.

Rabbani NR, Seville PC. The influence of formulation components on the aerosolisation properties of spray-dried powders. J Control Release. 2005;110:130–40.

Madaras-Kelly KJ, Larsson AJ, Rotschafer JC. A pharmacodynamic evaluation of ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin against two strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:703–10.

Ghani M, Soothill JS. Ceftazidime, gentamicin, and rifampicin, in combination, kill biofilms of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Can J Microbiol. 1997;43.

Sanders N, Rudolph C, Braeckmans K, De Smedt SC, Demeester J. Extracellular barriers in respiratory gene therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61:115–27.

Thomas SR, Ray A, Hodson ME, Pitt TL. Increased sputum amino acid concentrations and auxotrophy of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in severe cystic fibrosis lung disease. Thorax. 2000;55:795–7.

Zahm JM, GiroddeBentzmann S, Deneuville E, Perrot-Minnot C, Dabadie A, Pennaforte F, et al. Dose-dependent in vitro effect of recombinant human DNase on rheological and transport properties of cystic fibrosis respiratory mucus. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:381–6.

Hodson ME, Geddes DM, Bush A. Cystic fibrosis. London: Hodder Arnold; 2007.

Walker TS, Tomlin KL, Worthen GS, Poch KR, Lieber JG, Saavedra MT, et al. Enhanced Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development mediated by human neutrophils. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3693–701.

Tomkiewicz R, Kishore C, Freeman J, Rubin B. DNA and actin filament ultrastructure in cystic fibrosis sputum. In: Baum G, Priel Z, Roth Y, Liron N, Ostield E, editors. Cilia, Mucus, and Mucociliary Interactions. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc; 1998. p. 333–41.

Sheils CA, Kas J, Travassos W, Allen PG, Janmey PA, Wohl ME, et al. Actin filaments mediate DNA fiber formation in chronic inflammatory airway disease. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:919–27.

Broughton-Head VJ, Shur J, Carroll MP, Smith JR, Shute JK. Unfractionated heparin reduces the elasticity of sputum from patients with cystic fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L1240–9.

Whitchurch CB, Tolker-Nielsen T, Ragas PC, Mattick JS. Extracellular DNA required for bacterial biofilm formation. Science. 2002;295:1487.

Prosser BL, Taylor D, Dix BA, Cleeland R. Method of evaluating effects of antibiotics on bacterial biofilm. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:1502–6.

Costerton JW, Cheng KJ, Geesey GG, Ladd TI, Nickel JC, Dasgupta M, et al. Bacterial biofilms in nature and disease. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1987;41:435–64.

Bates RD, Nahata MC. Aerosolized dornase alpha (rhDNase) in cystic fibrosis. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1995;20:313–5.

Ratjen F. Treatment of early Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in patients with cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12:428–32.

Chalumeau MM, Tonnelier SS, D’Athis PP, Trluyer JJ-M, Gendrel DD, Brart GG, et al. Fluoroquinolone safety in pediatric patients: a prospective, multicenter, comparative cohort study in France. Pediatrics. 2003;111:e714–9.

Lee CKK, Boyle MP, Diener-West M, Brass-Ernst L, Noschese M, Zeitlin PL. Levofloxacin pharmacokinetics in adult cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2007;131:796–802.

Geller DEDE. Aerosol antibiotics in cystic fibrosis. Respir Care. 2009;54:658–70.

Pearson J. Inhalation Technologies—A Breath of Fresh Air. Drug Delivery Report. 2006;19–21. Spring/Summer).

Sweeney LG, Wang Z, Loebenberg R, Wong JP, Lange CF, Finlay WH. Spray-freeze-dried liposomal ciprofloxacin powder for inhaled aerosol drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2005;305:180–5.

Bosquillon C, Rouxhet PG, Ahimou F, Simon D, Culot C, Preat V, et al. Aerosolization properties, surface composition and physical state of spray-dried protein powders. J Control Release. 2004;99:357–67.

Ben-Jebria A, Chen D, Eskew ML, Vanbever R, Langer R, Edwards DA. Large porous particles for sustained protection from carbachol-induced bronchoconstriction in guinea pigs. Pharm Res. 1999;16:555–61.

Codrons V, Vanderbist F, Verbeeck RK, Arras M, Lison D, Préat V, et al. Systemic delivery of parathyroid hormone (1–34) using inhalation dry powders in rats. J Pharm Sci. 2003;92:938–50.

The United States Pharmacopeia: The National Formulary (USP32/NF27), The United States Pharmacopeial Convention, 2009.

Bosquillon C, Préat V, Vanbever R. Pulmonary delivery of growth hormone using dry powders and visualization of its local fate in rats. J Control Release. 2004;96:233–44.

Weuthen T, Roeder S, Brand P, Mllinger B, Scheuch G. In vitro testing of two formoterol dry powder inhalers at different flow rates. J Aerosol Med. 2002;15:297–303.

Tsapis N, Bennett D, Jackson B, Weitz DA, Edwards DA. Trojan particles: large porous carriers of nanoparticles for drug delivery. PNAS. 2002;99:12001–5.

Vehring R. Pharmaceutical particle engineering via spray drying. Pharm Res. 2008;25:999–1022.

Sung JC, Padilla DJ, Garcia-Contreras L, Verberkmoes JL, Durbin D, Peloquin CA, Elbert KJ, Hickey AJ, Edwards DA. Formulation and Pharmacokinetics of Self-Assembled Rifampicin Nanoparticle Systems for Pulmonary Delivery. Pharm Res. 2009.

Sung JC, Pulliam BL, Edwards DA. Nanoparticles for drug delivery to the lungs. Trends Biotechnol. 2007;25:563–70.

Ameri M, Maa Y-F. Spray drying of biopharmaceuticals: stability and process considerations. Drying Technol. 2006;24:763–8.

Shak S, Capon DJ, Hellmiss R, Marsters SA, Baker CL. Recombinant human DNase I reduces the viscosity of cystic fibrosis sputum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9188–92.

Sauer K, Camper AK, Ehrlich GD, Costerton JW, Davies DG. Pseudomonas aeruginosa displays multiple phenotypes during development as a biofilm. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:1140–54.

Anwar H, Dasgupta M, Lam K, Costerton JW. Tobramycin resistance of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm grown under iron limitation. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1989;24:647–55.

Høiby N, Johansen HK, Moser C, Song Z, Ciofu O, Kharazmi A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the in vitro and in vivo biofilm mode of growth. Microbes Infect. 2001;3:23–35.

Tsifansky MD, Yeo Y, Evgenov OV, Bellas E, Benjamin J, Kohane DS. Microparticles for Inhalational Delivery of Antipseudomonal Antibiotics. AAPS J. 2008.

Tré-Hardy M, Macé C, Manssouri NE, Vanderbist F, Traore H, Devleeschouwer MJ. Effect of antibiotic co-administration on young and mature biofilms of cystic fibrosis clinical isolates: the importance of the biofilm model. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;33:40–5.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (Yeo), 3M Non-tenured Faculty Grant (Yeo), and the China Scholarship Council (Y. Yang).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Fig. 1

(PDF 19 kb)

Supplementary Fig. 2

(PDF 19 kb)

Supplementary Fig. 3

(PDF 27 kb)

Supplementary Fig. 4

(PDF 22 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Tsifansky, M.D., Wu, CJ. et al. Inhalable Antibiotic Delivery Using a Dry Powder Co-delivering Recombinant Deoxyribonuclease and Ciprofloxacin for Treatment of Cystic Fibrosis. Pharm Res 27, 151–160 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-009-9991-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-009-9991-2