Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the potential of ascorbate as a novel ligand in the preparation of pharmaceutical nanocarriers with enhanced tumor-cell specific binding and cytotoxicity.

Methods

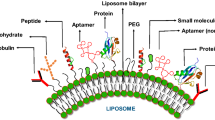

Palmitoyl ascorbate was incorporated into liposomes at varying concentrations. A stable formulation was selected based on size and zeta potential measurements. A co-culture of cancer cells with GFP expressing non-cancer cells was used to determine the specificity of palmitoyl ascorbate liposome binding. Liposomes were fluorescently labeled to facilitate analysis by flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy. The cytotoxic action of palmitoyl ascorbate liposomes against a variety of cell types was assayed using a standard metabolic assay. The cytotoxic effect of a low dose of paclitaxel incorporated in palmitoyl ascorbate liposomes on various cell lines was also determined.

Results

Palmitoyl ascorbate liposomes associated preferentially with various cancer cells compared to non-cancer cells in a co-culture model. Palmitoyl ascorbate liposomes exhibited anti-cancer toxicity in numerous cancer cell lines. Furthermore, ascorbate liposomes enhanced the effectiveness of encapsulated paclitaxel compared to paclitaxel encapsulated in ‘plain’ liposomes.

Conclusions

Surface modification of liposomes with ascorbate residues represents a novel way to target and kill certain types of tumor cells and additionally can potentiate the effect of paclitaxel delivered by the liposomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

S. J. Padayatty et al. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics: implications for oral and intravenous use. Ann. Intern. Med. 140(7):533–537 (2004).

E. Cameron, and L. Pauling. Supplemental ascorbate in the supportive treatment of cancer: Prolongation of survival times in terminal human cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 73(10):3685–3689 (1976) doi:10.1073/pnas.73.10.3685.

E. T. Creagan et al. Failure of high-dose vitamin C (ascorbic acid) therapy to benefit patients with advanced cancer. A controlled trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 301(13):687–690 (1979).

C. G. Moertel et al. High-dose vitamin C versus placebo in the treatment of patients with advanced cancer who have had no prior chemotherapy. A randomized double-blind comparison. N. Engl. J. Med. 312(3):137–141 (1985).

Q. Chen et al. Pharmacologic ascorbic acid concentrations selectively kill cancer cells: action as a pro-drug to deliver hydrogen peroxide to tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102(38):13604–13609 (2005) doi:10.1073/pnas.0506390102.

Q. Chen et al. Ascorbate in pharmacologic concentrations selectively generates ascorbate radical and hydrogen peroxide in extracellular fluid in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104(21):8749–8754 (2007) doi:10.1073/pnas.0702854104.

D. B. Agus, J. C. Vera, and D. W. Golde. Stromal cell oxidation: a mechanism by which tumors obtain vitamin C. Cancer Res. 59(18):4555–4558 (1999).

D. B. Agus et al. Vitamin C crosses the blood-brain barrier in the oxidized form through the glucose transporters. J. Clin. Invest. 100(11):2842–2848 (1997) doi:10.1172/JCI119832.

S. C. Rumsey et al. Dehydroascorbic acid transport by GLUT4 in Xenopus oocytes and isolated rat adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 275(36):28246–28253 (2000).

S. C. Rumsey et al. Glucose transporter isoforms GLUT1 and GLUT3 transport dehydroascorbic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 272(30):18982–1899 (1997) doi:10.1074/jbc.272.30.18982.

C. M. Kurbacher et al. Ascorbic acid (vitamin C) improves the antineoplastic activity of doxorubicin, cisplatin, and paclitaxel in human breast carcinoma cells in vitro. Cancer Lett. 103(2):183–189 (1996) doi:10.1016/0304-3835(96)04212-7.

C. D. Chiang et al. Ascorbic acid increases drug accumulation and reverses vincristine resistance of human non-small-cell lung-cancer cells. Biochem. J. 301(Pt 3):759–764 (1994).

A. M. Evens et al. Motexafin gadolinium generates reactive oxygen species and induces apoptosis in sensitive and highly resistant multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 105(3):1265–1273 (2005) doi:10.1182/blood-2004-03-0964.

N. J. Bahlis et al. Feasibility and correlates of arsenic trioxide combined with ascorbic acid-mediated depletion of intracellular glutathione for the treatment of relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Clin. Cancer Res. 8(12):3658–3668 (2002).

G. Rosenblat et al. Effect of ascorbic acid and its hydrophobic derivative palmitoyl ascorbate on the redox state of primary human fibroblasts. J. Med. Food. 4(2):107–115 (2001) doi:10.1089/109662001300341761.

S. Palma et al. Solubilization of hydrophobic drugs in octanoyl-6-O-ascorbic acid micellar dispersions. J. Pharm. Sci. 91(8):1810–1816 (2002) doi:10.1002/jps.10180.

D. Gopinath et al. Ascorbyl palmitate vesicles (Aspasomes): formation, characterization and applications. Int. J. Pharm. 271(1-2):95–113 (2004) doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2003.10.032.

F. Yuan et al. Microvascular permeability and interstitial penetration of sterically stabilized (stealth) liposomes in a human tumor xenograft. Cancer Res. 54(13):3352–3356 (1994).

H. Hashizume et al. Openings between defective endothelial cells explain tumor vessel leakiness. Am. J. Pathol. 156(4):1363–1380 (2000).

S. K. Hobbs et al. Regulation of transport pathways in tumor vessels: role of tumor type and microenvironment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95(8):4607–4612 (1998) doi:10.1073/pnas.95.8.4607.

W. G. Kaelin Jr. The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene and kidney cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 10(18 Pt 2):6290S–625S (2004) doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-sup-040025.

K. Block et al. NAD(P)H oxidases regulate HIF-2alpha protein expression. J. Biol. Chem. 282(11):8019–8026 (2007) doi:10.1074/jbc.M611569200.

M. Levine et al. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers: evidence for a recommended dietary allowance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93(8):3704–3709 (1996) doi:10.1073/pnas.93.8.3704.

M. V. Clement et al. The in vitro cytotoxicity of ascorbate depends on the culture medium used to perform the assay and involves hydrogen peroxide. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 3(1):157–163 (2001) doi:10.1089/152308601750100687.

K. K. Parsons et al. Ascorbic acid-independent synthesis of collagen in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 290(6):E1131–E1139 (2006) doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00339.2005.

S. Telang et al. Depletion of ascorbic acid restricts angiogenesis and retards tumor growth in a mouse model. Neoplasia. 9(1):47–56 (2007) doi:10.1593/neo.06664.

R. C. Rose, and A. M. Bode. Biology of free radical scavengers: an evaluation of ascorbate. FASEB J. 7(12):1135–1142 (1993).

Acknowledgements

This research is based on a hypothesis originated and proposed by Anthony R. Manganaro. Funding was provided by Anthony R. Manganaro.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

D’Souza, G.G.M., Wang, T., Rockwell, K. et al. Surface Modification of Pharmaceutical Nanocarriers with Ascorbate Residues Improves their Tumor-Cell Association and Killing and the Cytotoxic Action of Encapsulated Paclitaxel In Vitro . Pharm Res 25, 2567–2572 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-008-9674-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-008-9674-4