Abstract

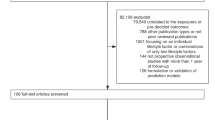

This year, more than 1 million Americans and more than 10 million people worldwide are expected to be diagnosed with cancer, a disease commonly believed to be preventable. Only 5–10% of all cancer cases can be attributed to genetic defects, whereas the remaining 90–95% have their roots in the environment and lifestyle. The lifestyle factors include cigarette smoking, diet (fried foods, red meat), alcohol, sun exposure, environmental pollutants, infections, stress, obesity, and physical inactivity. The evidence indicates that of all cancer-related deaths, almost 25–30% are due to tobacco, as many as 30–35% are linked to diet, about 15–20% are due to infections, and the remaining percentage are due to other factors like radiation, stress, physical activity, environmental pollutants etc. Therefore, cancer prevention requires smoking cessation, increased ingestion of fruits and vegetables, moderate use of alcohol, caloric restriction, exercise, avoidance of direct exposure to sunlight, minimal meat consumption, use of whole grains, use of vaccinations, and regular check-ups. In this review, we present evidence that inflammation is the link between the agents/factors that cause cancer and the agents that prevent it. In addition, we provide evidence that cancer is a preventable disease that requires major lifestyle changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

After sequencing his own genome, pioneer genomic researcher Craig Venter remarked at a leadership for the twenty-first century conference, “Human biology is actually far more complicated than we imagine. Everybody talks about the genes that they received from their mother and father, for this trait or the other. But in reality, those genes have very little impact on life outcomes. Our biology is way too complicated for that and deals with hundreds of thousands of independent factors. Genes are absolutely not our fate. They can give us useful information about the increased risk of a disease, but in most cases they will not determine the actual cause of the disease, or the actual incidence of somebody getting it. Most biology will come from the complex interaction of all the proteins and cells working with environmental factors, not driven directly by the genetic code” (http://indiatoday.digitaltoday.in/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&isseid=48&id=6022§ionid=30&Itemid=1).

This statement is very important because looking to the human genome for solutions to most chronic illnesses, including the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of cancer, is overemphasized in today’s world. Observational studies, however, have indicated that as we migrate from one country to another, our chances of being diagnosed with most chronic illnesses are determined not by the country we come from but by the country we migrate to (1–4). In addition, studies with identical twins have suggested that genes are not the source of most chronic illnesses. For instance, the concordance between identical twins for breast cancer was found to be only 20% (5). Instead of our genes, our lifestyle and environment account for 90–95% of our most chronic illnesses.

Cancer continues to be a worldwide killer, despite the enormous amount of research and rapid developments seen during the past decade. According to recent statistics, cancer accounts for about 23% of the total deaths in the USA and is the second most common cause of death after heart disease (6). Death rates for heart disease, however, have been steeply decreasing in both older and younger populations in the USA from 1975 through 2002. In contrast, no appreciable differences in death rates for cancer have been observed in the United States (6).

By 2020, the world population is expected to have increased to 7.5 billion; of this number, approximately 15 million new cancer cases will be diagnosed, and 12 million cancer patients will die (7). These trends of cancer incidence and death rates again remind us of Dr. John Bailer’s May 1985 judgment of the US national cancer program as a “qualified failure,” a judgment made 14 years after President Nixon’s official declaration of the “War on Cancer.” Even after an additional quarter century of extensive research, researchers are still trying to determine whether cancer is preventable and are asking “If it is preventable, why are we losing the war on cancer?” In this review, we attempt to answer this question by analyzing the potential risk factors of cancer and explore our options for modulating these risk factors.

Cancer is caused by both internal factors (such as inherited mutations, hormones, and immune conditions) and environmental/acquired factors (such as tobacco, diet, radiation, and infectious organisms; Fig. 1). The link between diet and cancer is revealed by the large variation in rates of specific cancers in various countries and by the observed changes in the incidence of cancer in migrating. For example, Asians have been shown to have a 25 times lower incidence of prostate cancer and a ten times lower incidence of breast cancer than do residents of Western countries, and the rates for these cancers increase substantially after Asians migrate to the West (http://www.dietandcancerreportorg/?p=ER).

The role of genes and environment in the development of cancer. A The percentage contribution of genetic and environmental factors to cancer. The contribution of genetic factors and environmental factors towards cancer risk is 5–10% and 90–95% respectively. B Family risk ratios for selected cancers. The numbers represent familial risk ratios, defined as the risk to a given type of relative of an affected individual divided by the population prevalence. The data shown here is taken from a study conducted in Utah to determine the frequency of cancer in the first-degree relatives (parents + siblings + offspring). The familial risk ratios were assessed as the ratio of the observed number of cancer cases among the first degree relatives divided by the expected number derived from the control relatives, based on the years of birth (cohort) of the case relatives. In essence, this provides an age-adjusted risk ratio to first-degree relatives of cases compared with the general population. C Percentage contribution of each environmental factor. The percentages represented here indicate the attributable-fraction of cancer deaths due to the specified environmental risk factor.

The importance of lifestyle factors in the development of cancer was also shown in studies of monozygotic twins (8). Only 5–10% of all cancers are due to an inherited gene defect. Various cancers that have been linked to genetic defects are shown in Fig. 2. Although all cancers are a result of multiple mutations (9, 10), these mutations are due to interaction with the environment (11, 12).

These observations indicate that most cancers are not of hereditary origin and that lifestyle factors, such as dietary habits, smoking, alcohol consumption, and infections, have a profound influence on their development (13). Although the hereditary factors cannot be modified, the lifestyle and environmental factors are potentially modifiable. The lesser hereditary influence of cancer and the modifiable nature of the environmental factors point to the preventability of cancer. The important lifestyle factors that affect the incidence and mortality of cancer include tobacco, alcohol, diet, obesity, infectious agents, environmental pollutants, and radiation.

RISK FACTORS OF CANCER

Tobacco

Smoking was identified in 1964 as the primary cause of lung cancer in the US Surgeon General’s Advisory Commission Report (http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/NN/Views/AlphaChron/date/10006/05/01/2008), and ever since, efforts have been ongoing to reduce tobacco use. Tobacco use increases the risk of developing at least 14 types of cancer (Fig. 3). In addition, it accounts for about 25–30% of all deaths from cancer and 87% of deaths from lung cancer. Compared with nonsmokers, male smokers are 23 times and female smokers 17 times more likely to develop lung cancer (http://www.cancer.org/docroot/STT/content/STT_1x_Cancer_Facts_and_Figures_2008.asp accessed on 05/01/2008). The carcinogenic effects of active smoking are well documented; the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, for example, in 1993 classified environmental tobacco smoke (from passive smoking) as a known (Group A) human lung carcinogen (http://cfpub2.epa.gov/ncea/cfm/recordisplay.cfm?deid=2835 accessed on 05/01/2008). Tobacco contains at least 50 carcinogens. For example, one tobacco metabolite, benzopyrenediol epoxide, has a direct etiologic association with lung cancer (14). Among all developed countries considered in total, the prevalence of smoking has been slowly declining; however, in the developing countries where 85% of the world’s population resides, the prevalence of smoking is increasing. According to studies of recent trends in tobacco usage, developing countries will consume 71% of the world’s tobacco by 2010, with 80% increased usage projected for East Asia (http://www.fao.org/DOCREP/006/Y4956E/Y4956E00.HTM accessed on 01/11/08). The use of accelerated tobacco-control programs, with an emphasis in areas where usage is increasing, will be the only way to reduce the rates of tobacco-related cancer mortality.

Cancers that have been linked to alcohol and smoking. Percentages represent the cancer mortality attributable to alcohol and smoking in men and women as reported by Irigaray et al. (see 13).

How smoking contributes to cancer is not fully understood. We do know that smoking can alter a large number of cell-signaling pathways. Results from studies in our group have established a link between cigarette smoke and inflammation. Specifically, we showed that tobacco smoke can induce activation of NF-κB, an inflammatory marker (15,16). Thus, anti-inflammatory agents that can suppress NF-κB activation may have potential applications against cigarette smoke.

We also showed that curcumin, derived from the dietary spice turmeric, can block the NF-κB induced by cigarette smoke (15). In addition to curcumin, we discovered that several natural phytochemicals also inhibit the NF-κB induced by various carcinogens (17). Thus, the carcinogenic effects of tobacco appear to be reduced by these dietary agents. A more detailed discussion of dietary agents that can block inflammation and thereby provide chemopreventive effects is presented in the following section.

Alcohol

The first report of the association between alcohol and an increased risk of esophageal cancer was published in 1910 (18). Since then, a number of studies have revealed that chronic alcohol consumption is a risk factor for cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract, including cancers of the oral cavity, pharynx, hypopharynx, larynx, and esophagus (18–21), as well as for cancers of the liver, pancreas, mouth, and breast (Fig. 3). Williams and Horn (22), for example, reported an increased risk of breast cancer due to alcohol. In addition, a collaborative group who studied hormonal factors in breast cancer published their findings from a reanalysis of more than 80% of individual epidemiological studies that had been conducted worldwide on the association between alcohol and breast cancer risk in women. Their analysis showed a 7.1% increase in relative risk of breast cancer for each additional 10 g/day intake of alcohol (23). In another study, Longnecker et al., (24) showed that 4% of all newly diagnosed cases of breast cancer in the USA are due to alcohol use. In addition to it being a risk factor for breast cancer, heavy intake of alcohol (more than 50–70 g/day) is a well-established risk factor for liver (25) and colorectal (26,27) cancers.

There is also evidence of a synergistic effect between heavy alcohol ingestion and hepatitis C virus (HCV) or hepatitis B virus (HBV), which presumably increases the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) by more actively promoting cirrhosis. For example, Donato et al. (28) reported that among alcohol drinkers, HCC risk increased linearly with a daily intake of more than 60 g. However, with the concomitant presence of HCV infection, the risk of HCC was two times greater than that observed with alcohol use alone (i.e., a positive synergistic effect). The relationship between alcohol and inflammation has also been well established, especially in terms of alcohol-induced inflammation of the liver.

How alcohol contributes to carcinogenesis is not fully understood but ethanol may play a role. Study findings suggest that ethanol is not a carcinogen but is a cocarcinogen (29). Specifically, when ethanol is metabolized, acetaldehyde and free radicals are generated; free radicals are believed to be predominantly responsible for alcohol-associated carcinogenesis through their binding to DNA and proteins, which destroys folate and results in secondary hyperproliferation. Other mechanisms by which alcohol stimulates carcinogenesis include the induction of cytochrome P-4502E1, which is associated with enhanced production of free radicals and enhanced activation of various procarcinogens present in alcoholic beverages; a change in metabolism and in the distribution of carcinogens, in association with tobacco smoke and diet; alterations in cell-cycle behavior such as cell-cycle duration leading to hyperproliferation; nutritional deficiencies, for example, of methyl, vitamin E, folate, pyridoxal phosphate, zinc, and selenium; and alterations of the immune system. Tissue injury, such as that occurring with cirrhosis of the liver, is a major prerequisite to HCC. In addition, alcohol can activate the NF-κB proinflammatory pathway (30), which can also contribute to tumorigenesis (31). Furthermore, it has been shown that benzopyrene, a cigarette smoke carcinogen, can penetrate the esophagus when combined with ethanol (32). Thus anti-inflammatory agents may be effective for the treatment of alcohol-induced toxicity.

In the upper aerodigestive tract, 25–68% of cancers are attributable to alcohol, and up to 80% of these tumors can be prevented by abstaining from alcohol and smoking (33). Globally, the attributable fraction of cancer deaths due to alcohol drinking is reported to be 3.5% (34). The number of deaths from cancers known to be related to alcohol consumption in the USA could be as low as 6% (as in Utah) or as high as 28% (as in Puerto Rico). These numbers vary from country to country, and in France have approached 20% in males (18).

Diet

In 1981, Doll and Peto (21) estimated that approximately 30–35% of cancer deaths in the USA were linked to diet (Fig. 4). The extent to which diet contributes to cancer deaths varies a great deal, according to the type of cancer (35). For example, diet is linked to cancer deaths in as many as 70% of colorectal cancer cases. How diet contributes to cancer is not fully understood. Most carcinogens that are ingested, such as nitrates, nitrosamines, pesticides, and dioxins, come from food or food additives or from cooking.

Cancer deaths (%) linked to diet as reported by Willett (see 35).

Heavy consumption of red meat is a risk factor for several cancers, especially for those of the gastrointestinal tract, but also for colorectal (36–38), prostate (39), bladder (40), breast (41), gastric (42), pancreatic, and oral (43) cancers. Although a study by Dosil-Diaz et al., (44) showed that meat consumption reduced the risk of lung cancer, such consumption is commonly regarded as a risk for cancer for the following reasons. The heterocyclic amines produced during the cooking of meat are carcinogens. Charcoal cooking and/or smoke curing of meat produces harmful carbon compounds such as pyrolysates and amino acids, which have a strong cancerous effect. For instance, PhIP (2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenyl-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine) is the most abundant mutagen by mass in cooked beef and is responsible for ~20% of the total mutagenicity found in fried beef. Daily intake of PhIP among Americans is estimated to be 280–460 ng/day per person (45).

Nitrites and nitrates are used in meat because they bind to myoglobin, inhibiting botulinum exotoxin production; however, they are powerful carcinogens (46). Long-term exposure to food additives such as nitrite preservatives and azo dyes has been associated with the induction of carcinogenesis (47). Furthermore, bisphenol from plastic food containers can migrate into food and may increase the risk of breast (48) and prostate (49) cancers. Ingestion of arsenic may increase the risk of bladder, kidney, liver, and lung cancers (50). Saturated fatty acids, trans fatty acids, and refined sugars and flour present in most foods have also been associated with various cancers. Several food carcinogens have been shown to activate inflammatory pathways.

Obesity

According to an American Cancer Society study (51), obesity has been associated with increased mortality from cancers of the colon, breast (in postmenopausal women), endometrium, kidneys (renal cell), esophagus (adenocarcinoma), gastric cardia, pancreas, prostate, gallbladder, and liver (Fig. 5). Findings from this study suggest that of all deaths from cancer in the United States, 14% in men and 20% in women are attributable to excess weight or obesity. Increased modernization and a Westernized diet and lifestyle have been associated with an increased prevalence of overweight people in many developing countries (52).

Various cancers that have been linked to obesity. In the USA overweight and obesity could account for 14% of all deaths from cancer in men and 20% of those in women (see 51).

Studies have shown that the common denominators between obesity and cancer include neurochemicals; hormones such as insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF-1), insulin, leptin; sex steroids; adiposity; insulin resistance; and inflammation (53).

Involvement of signaling pathways such as the IGF/insulin/Akt signaling pathway, the leptin/JAK/STAT pathway, and other inflammatory cascades have also been linked with both obesity and cancer (53). For instance, hyperglycemia, has been shown to activate NF-κB (54), which could link obesity with cancer. Also known to activate NF-κB are several cytokines produced by adipocytes, such as leptin, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and interleukin-1 (IL-1) (55). Energy balance and carcinogenesis has been closely linked (53). However, whether inhibitors of these signaling cascades can reduce obesity-related cancer risk remains unanswered. Because of the involvement of multiple signaling pathways, a potential multitargeting agent will likely be needed to reduce obesity-related cancer risk.

Infectious Agents

Worldwide, an estimated 17.8% of neoplasms are associated with infections; this percentage ranges from less than 10% in high-income countries to 25% in African countries (56, 57). Viruses account for most infection-caused cancers (Fig. 6). Human papillomavirus, Epstein Barr virus, Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpes virus, human T-lymphotropic virus 1, HIV, HBV, and HCV are associated with risks for cervical cancer, anogenital cancer, skin cancer, nasopharyngeal cancer, Burkitt’s lymphoma, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, adult T-cell leukemia, B-cell lymphoma, and liver cancer.

Various cancers that have been linked to infection. The estimated total of infection attributable cancer in the year 2002 is 17.8% of the global cancer burden. The infectious agents associated with each type of cancer is shown in the bracket. HPV Human papilloma virus, HTLV human T-cell leukemia virus, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, EBV Epstein–Barr virus (see 57).

In Western developed countries, human papillomavirus and HBV are the most frequently encountered oncogenic DNA viruses. Human papillomavirus is directly mutagenic by inducing the viral genes E6 and E7 (58), whereas HBV is believed to be indirectly mutagenic by generating reactive oxygen species through chronic inflammation (59–61). Human T-lymphotropic virus is directly mutagenic, whereas HCV (like HBV) is believed to produce oxidative stress in infected cells and thus to act indirectly through chronic inflammation (62, 63). However, other microorganisms, including selected parasites such as Opisthorchis viverrini or Schistosoma haematobium and bacteria such as Helicobacter pylori, may also be involved, acting as cofactors and/or carcinogens (64).

The mechanisms by which infectious agents promote cancer are becoming increasingly evident. Infection-related inflammation is the major risk factor for cancer, and almost all viruses linked to cancer have been shown to activate the inflammatory marker, NF-κB (65). Similarly, components of Helicobacter pylori have been shown to activate NF-κB (66). Thus, agents that can block chronic inflammation should be effective in treating these conditions.

Environmental Pollution

Environmental pollution has been linked to various cancers (Fig. 7). It includes outdoor air pollution by carbon particles associated with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs); indoor air pollution by environmental tobacco smoke, formaldehyde, and volatile organic compounds such as benzene and 1,3-butadiene (which may particularly affect children); food pollution by food additives and by carcinogenic contaminants such as nitrates, pesticides, dioxins, and other organochlorines; carcinogenic metals and metalloids; pharmaceutical medicines; and cosmetics (64).

Various cancers that have been linked to environmental carcinogens. The carcinogens linked to each cancer is shown inside bracket. (see 64).

Numerous outdoor air pollutants such as PAHs increase the risk of cancers, especially lung cancer. PAHs can adhere to fine carbon particles in the atmosphere and thus penetrate our bodies primarily through breathing. Long-term exposure to PAH-containing air in polluted cities was found to increase the risk of lung cancer deaths. Aside from PAHs and other fine carbon particles, another environmental pollutant, nitric oxide, was found to increase the risk of lung cancer in a European population of nonsmokers. Other studies have shown that nitric oxide can induce lung cancer and promote metastasis. The increased risk of childhood leukemia associated with exposure to motor vehicle exhaust was also reported (64).

Indoor air pollutants such as volatile organic compounds and pesticides increase the risk of childhood leukemia and lymphoma, and children as well as adults exposed to pesticides have increased risk of brain tumors, Wilm’s tumors, Ewing’s sarcoma, and germ cell tumors. In utero exposure to environmental organic pollutants was found to increase the risk for testicular cancer. In addition, dioxan, an environmental pollutant from incinerators, was found to increase the risk of sarcoma and lymphoma.

Long-term exposure to chlorinated drinking water has been associated with increased risk of cancer. Nitrates, in drinking water, can transform to mutagenic N-nitroso compounds, which increase the risk of lymphoma, leukemia, colorectal cancer, and bladder cancer (64).

Radiation

Up to 10% of total cancer cases may be induced by radiation (64), both ionizing and nonionizing, typically from radioactive substances and ultraviolet (UV), pulsed electromagnetic fields. Cancers induced by radiation include some types of leukemia, lymphoma, thyroid cancers, skin cancers, sarcomas, lung and breast carcinomas. One of the best examples of increased risk of cancer after exposure to radiation is the increased incidence of total malignancies observed in Sweden after exposure to radioactive fallout from the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. Radon and radon decay products in the home and/or at workplaces (such as mines) are the most common sources of exposure to ionizing radiation. The presence of radioactive nuclei from radon, radium, and uranium was found to increase the risk of gastric cancer in rats. Another source of radiation exposure is x-rays used in medical settings for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes. In fact, the risk of breast cancer from x-rays is highest among girls exposed to chest irradiation at puberty, a time of intense breast development. Other factors associated with radiation-induced cancers in humans are patient age and physiological state, synergistic interactions between radiation and carcinogens, and genetic susceptibility toward radiation.

Nonionizing radiation derived primarily from sunlight includes UV rays, which are carcinogenic to humans. Exposure to UV radiation is a major risk for various types of skin cancers including basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Along with UV exposure from sunlight, UV exposure from sunbeds for cosmetic tanning may account for the growing incidence of melanoma. Depletion of the ozone layer in the stratosphere can augment the dose-intensity of UVB and UVC, which can further increase the incidence of skin cancer.

Low-frequency electromagnetic fields can cause clastogenic DNA damage. The sources of electromagnetic field exposure are high-voltage power lines, transformers, electric train engines, and more generally, all types of electrical equipments. An increased risk of cancers such as childhood leukemia, brain tumors and breast cancer has been attributed to electromagnetic field exposure. For instance, children living within 200 m of high-voltage power lines have a relative risk of leukemia of 69%, whereas those living between 200 and 600 m from these power lines have a relative risk of 23%. In addition, a recent meta-analysis of all available epidemiologic data showed that daily prolonged use of mobile phones for 10 years or more showed a consistent pattern of an increased risk of brain tumors (64).

PREVENTION OF CANCER

The fact that only 5–10% of all cancer cases are due to genetic defects and that the remaining 90–95% are due to environment and lifestyle provides major opportunities for preventing cancer. Because tobacco, diet, infection, obesity, and other factors contribute approximately 25–30%, 30–35%, 15–20%, 10–20%, and 10–15%, respectively, to the incidence of all cancer deaths in the USA, it is clear how we can prevent cancer. Almost 90% of patients diagnosed with lung cancer are cigarette smokers; and cigarette smoking combined with alcohol intake can synergistically contribute to tumorigenesis. Similarly, smokeless tobacco is responsible for 400,000 cases (4% of all cancers) of oral cancer worldwide. Thus avoidance of tobacco products and minimization of alcohol consumption would likely have a major effect on cancer incidence.

Infection by various bacteria and viruses (Fig. 6) is another very prominent cause of various cancers. Vaccines for cervical cancer and HCC should help prevent some of these cancers, and a cleaner environment and modified lifestyle behavior would be even more helpful in preventing infection-caused cancers.

The first FDA approved chemopreventive agent was tamoxifen, for reducing the risk of breast cancer. This agent was found to reduce the breast cancer incidence by 50% in women at high risk. With tamoxifen, there is an increased risk of serious side effects such as uterine cancer, blood clots, ocular disturbances, hypercalcemia, and stroke (http://www.fda.gov/cder/foi/appletter/1998/17970s40.pdf). Recently it has been shown that a osteoporosis drug raloxifene is as effective as tamoxifen in preventing estrogen-receptor-positive, invasive breast cancer but had fewer side effects than tamoxifen. Though it is better than tamoxifen with respect to side effects, it can cause blood clots and stroke. Other potential side effects of raloxifene include hot flashes, leg cramps, swelling of the legs and feet, flu-like symptoms, joint pain, and sweating (http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2007/NEW01698.html).

The second chemopreventive agent to reach to clinic was finasteride, for prostate cancer, which was found to reduce incidence by 25% in men at high risk. The recognized side effects of this agent include erectile dysfunction, lowered sexual desire, impotence and gynecomastia (http://www.cancer.org/docroot/cri/content/cri_2_4_2x_can_prostate_cancer_be_prevented_36.asp). Celecoxib, a COX-2 inhibitor is another approved agent for prevention of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). However, the chemopreventive benefit of celecoxib is at the cost of its serious cardiovascular harm (http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/infopage/cox2/NSAIDdecisionMemo.pdf). The serious side effects of the FDA approved chemopreventive drugs is an issue of particular concern when considering long-term administration of a drug to healthy people who may or may not develop cancer. This clearly indicates the need for agents, which are safe and efficacious in preventing cancer. Diet derived natural products will be potential candidates for this purpose.

Diet, obesity, and metabolic syndrome are very much linked to various cancers and may account for as much as 30–35% of cancer deaths, indicating that a reasonably good fraction of cancer deaths can be prevented by modifying the diet. Extensive research has revealed that a diet consisting of fruits, vegetables, spices, and grains has the potential to prevent cancer (Fig. 8). The specific substances in these dietary foods that are responsible for preventing cancer and the mechanisms by which they achieve this have also been examined extensively. Various phytochemicals have been identified in fruits, vegetables, spices, and grains that exhibit chemopreventive potential (Fig. 9), and numerous studies have shown that a proper diet can help protect against cancer (46, 67–69). Below is a description of selected dietary agents and diet-derived phytochemicals that have been studied extensively to determine their role in cancer prevention.

Fruits, vegetables, spices, condiments and cereals with potential to prevent cancer. Fruits include 1 apple, 2 apricot, 3 banana, 4 blackberry, 5 cherry, 6 citrus fruits, 7 dessert date, 8 durian, 9 grapes, 10 guava, 11 Indian gooseberry, 12 mango, 13 malay apple, 14 mangosteen, 15 pineapple, 16 pomegranate. Vegetables include 1 artichok, 2 avocado, 3 brussels sprout, 4 broccoli, 5 cabbage, 6 cauliflower, 7 carrot, 8 daikon 9 kohlrabi, 10 onion, 11 tomato, 12 turnip, 13 ulluco, 14 water cress, 15 okra, 16 potato, 17 fiddle head, 18 radicchio, 19 komatsuna, 20 salt bush, 21 winter squash, 22 zucchini, 23 lettuce, 24 spinach. Spices and condiments include 1 turmeric, 2 cardamom, 3 coriander, 4 black pepper, 5 clove, 6 fennel, 7 rosemary, 8 sesame seed, 9 mustard, 10 licorice, 11 garlic, 12 ginger, 13 parsley, 14 cinnamon, 15 curry leaves, 16 kalonji, 17 fenugreek, 18 camphor, 19 pecan, 20 star anise, 21 flax seed, 22 black mustard, 23 pistachio, 24 walnut, 25 peanut, 26 cashew nut. Cereals include 1 rice, 2 wheat, 3 oats, 4 rye, 5 barley, 6 maize, 7 jowar, 8 pearl millet, 9 proso millet, 10 foxtail millet, 11 little millet, 12 barnyard millet, 13 kidney bean, 14 soybean, 15 mung bean, 16 black bean, 17 pigeon pea, 18 green pea, 19 scarlet runner bean, 20 black beluga, 21 brown spanish pardina, 22 green, 23 green (eston), 24 ivory white, 25 multicolored blend, 26 petite crimson, 27 petite golden, 28 red chief.

Phytochemicals derived from fruits, vegetables, spices, condiments and cereals with potential to prevent cancer. 1 diosgenin, 2 glycyrrhizin, 3 glycyrrhetinic acid, 4 18-β-glycyrrhetinic acid, 5 oleandrin, 6 oleanolic acid, 7 betulinic acid, 8 lupeol, 9 guggulsterone, 10 celastrol, 11 ursolic acid, 12 acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid, 13 1’-actoxychavicol acetate, 14 α-lipoic acid 15 yakuchinone A, 16 yakuchinone B, 17 curcumin, 18 gingerol, 19 resveratrol, 20 piceatannol 21 genistein, 22 capsaicin, 23 dibenzoylmethane, 24 piperine, 25 kahweol, 26 indiruibin-3’-monoxime, 27 caffeic acid phenethyl ester, 28 emodin, 29 eugenol, 30 linalol, 31 quinic acid, 32 garcinol, 33 sesamin, 34 theaflavin-3,3’-digallate, 35 sanguinarine, 36 silymarin, 37 mangostin, 38 mangiferin, 39 butein, 40 berberine, 41 glabridin, 42 myricetin, 43 carnosol, 44 β-lapachone, 45 evodiamine, 46 wogonin, 47 apigenin, 48 (-)-epigatechin, 49 tanshinones IIA, 50 tanshinones I, 51 (-)-epicatechin gallate, 52 epigallocatechin gallate, 53 carnosol, 54 zerumbone, 55 sulforaphane, 56 phytic acid, 57 allicin, 58 benzyl isothiocyanate, 59 baicalin, 60 ascorbic acid, 61 anethole, 62 indole 3-carbinol, 63 phenyl isothiocyanate, 64 thymoquinone, 65 plumbagin, 66 γ-tocotrienol, 67 lutein, 68 β-cryptoxanthine, 69 β-carotene, 70 lycopene, 71 α-tocoperol.

Fruits and Vegetables

The protective role of fruits and vegetables against cancers that occur in various anatomical sites is now well supported (46,69). In 1966, Wattenberg (70) proposed for the first time that the regular consumption of certain constituents in fruits and vegetables might provide protection from cancer. Doll and Peto (21) showed that 75–80% of cancer cases diagnosed in the USA in 1981 might have been prevented by lifestyle changes. According to a 1997 estimate, approximately 30–40% of cancer cases worldwide were preventable by feasible dietary means (http://www.dietandcancerreportorg/?p=ER). Several studies have addressed the cancer chemopreventive effects of the active components derived from fruits and vegetables.

More than 25,000 different phytochemicals have been identified that may have potential against various cancers. These phytochemicals have advantages because they are safe and usually target multiple cell-signaling pathways (71). Major chemopreventive compounds identified from fruits and vegetables includes carotenoids, vitamins, resveratrol, quercetin, silymarin, sulphoraphane and indole-3-carbinol.

Carotenoids

Various natural carotenoids present in fruits and vegetables were reported to have anti-inflammatory and anticarcinogenic activity. Lycopene is one of the main carotenoids in the regional Mediterranean diet and can account for 50% of the carotenoids in human serum. Lycopene is present in fruits, including watermelon, apricots, pink guava, grapefruit, rosehip, and tomatoes. A wide variety of processed tomato-based products account for more than 85% of dietary lycopene. The anticancer activity of lycopene has been demonstrated in both in vitro and in vivo tumor models as well as in humans. The proposed mechanisms for the anticancer effect of lycopene involve ROS scavenging, up-regulation of detoxification systems, interference with cell proliferation, induction of gap-junctional communication, inhibition of cell-cycle progression, and modulation of signal transduction pathways. Other carotenoids reported to have anticancer activity include beta-carotene, alpha-carotene, lutein, zeaxanthin, beta-cryptoxanthin, fucoxanthin, astaxanthin, capsanthin, crocetin, and phytoene (72).

Resveratrol

The stilbene resveratrol has been found in fruits such as grapes, peanuts, and berries. Resveratrol exhibits anticancer properties against a wide variety of tumors, including lymphoid and myeloid cancers, multiple myeloma, and cancers of the breast, prostate, stomach, colon, and pancreas. The growth-inhibitory effects of resveratrol are mediated through cell-cycle arrest; induction of apoptosis via Fas/CD95, p53, ceramide activation, tubulin polymerization, mitochondrial and adenylyl cyclase pathways; up-regulation of p21 p53 and Bax; down-regulation of survivin, cyclin D1, cyclin E, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and cellular inhibitor of apoptosis proteins; activation of caspases; suppression of nitric oxide synthase; suppression of transcription factors such as NF-κB, AP-1, and early growth response-1; inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and lipoxygenase; suppression of adhesion molecules; and inhibition of angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis. Limited data in humans have revealed that resveratrol is pharmacologically safe. As a nutraceutical, resveratrol is commercially available in the USA and Europe in 50 µg to 60 mg doses. Currently, structural analogues of resveratrol with improved bioavailability are being pursued as potential chemopreventive and therapeutic agents for cancer (73).

Quercetin

The flavone quercetin (3,3′,4′,5,7-pentahydroxyflavone), one of the major dietary flavonoids, is found in a broad range of fruits, vegetables, and beverages such as tea and wine, with a daily intake in Western countries of 25–30 mg. The antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative, and apoptotic effects of the molecule have been largely analyzed in cell culture models, and it is known to block NF-κB activation. In animal models, quercetin has been shown to inhibit inflammation and prevent colon and lung cancer. A phase 1 clinical trial indicated that the molecule can be safely administered and that its plasma levels are sufficient to inhibit lymphocyte tyrosine kinase activity. Consumption of quercetin in onions and apples was found to be inversely associated with lung cancer risk in Hawaii. The effect of onions was particularly strong against squamous cell carcinoma. In another study, an increased plasma level of quercetin after a meal of onions was accompanied by increased resistance to strand breakage in lymphocytic DNA and decreased levels of some oxidative metabolites in the urine (74).

Silymarin

The flavonoid silymarin (silybin, isosilybin, silychristin, silydianin, and taxifolin) is commonly found in the dried fruit of the milk thistle plant Silybum marianum. Although silymarin’s role as an antioxidant and hepatoprotective agent is well known, its role as an anticancer agent is just emerging. The anti-inflammatory effects of silymarin are mediated through suppression of NF-κB-regulated gene products, including COX-2, lipoxygenase (LOX), inducible NO synthase, TNF, and IL-1. Numerous studies have indicated that silymarin is a chemopreventive agent in vivo against various carcinogens/tumor promoters, including UV light, 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene (DMBA), phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, and others. Silymarin has also been shown to sensitize tumors to chemotherapeutic agents through down-regulation of the MDR protein and other mechanisms. It binds to both estrogen and androgen receptors and down-regulates prostate specific antigen. In addition to its chemopreventive effects, silymarin exhibits activity against tumors (e.g., prostate and ovary) in rodents. Various clinical trials have indicated that silymarin is bioavailable and pharmacologically safe. Studies are now in progress to demonstrate the clinical efficacy of silymarin against various cancers (75).

Indole-3-carbinol

The flavonoid indole-3-carbinol (I3C) is present in vegetables such as cabbage, broccoli, brussels sprout, cauliflower, and daikon artichoke. The hydrolysis product of I3C metabolizes to a variety of products, including the dimer 3,3′-diindolylmethane. Both I3C and 3,3′-diindolylmethane exert a variety of biological and biochemical effects, most of which appear to occur because I3C modulates several nuclear transcription factors. I3C induces phase 1 and phase 2 enzymes that metabolize carcinogens, including estrogens. I3C has also been found to be effective in treating some cases of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis and may have other clinical uses (76).

Sulforaphane

Sulforaphane (SFN) is an isothiothiocyanate found in cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli. Its chemopreventive effects have been established in both in vitro and in vivo studies. The mechanisms of action of SFN include inhibition of phase 1 enzymes, induction of phase 2 enzymes to detoxify carcinogens, cell-cycle arrest, induction of apoptosis, inhibition of histone deacetylase, modulation of the MAPK pathway, inhibition of NF-κB, and production of ROS. Preclinical and clinical studies of this compound have suggested its chemopreventive effects at several stages of carcinogenesis. In a clinical trial, SFN was given to eight healthy women an hour before they underwent elective reduction mammoplasty. Induction in NAD(P)H/quinone oxidoreductase and heme oxygenase-1 was observed in the breast tissue of all patients, indicating the anticancer effect of SFN (77).

Teas and Spices

Spices are used all over the world to add flavor, taste, and nutritional value to food. A growing body of research has demonstrated that phytochemicals such as catechins (green tea), curcumin (turmeric), diallyldisulfide (garlic), thymoquinone (black cumin) capsaicin (red chili), gingerol (ginger), anethole (licorice), diosgenin (fenugreek) and eugenol (clove, cinnamon) possess therapeutic and preventive potential against cancers of various anatomical origins. Other phytochemicals with this potential include ellagic acid (clove), ferulic acid (fennel, mustard, sesame), apigenin (coriander, parsley), betulinic acid (rosemary), kaempferol (clove, fenugreek), sesamin (sesame), piperine (pepper), limonene (rosemary), and gambogic acid (kokum). Below is a description of some important phytochemicals associated with cancer.

Catechins

More than 3,000 studies have shown that catechins derived from green and black teas have potential against various cancers. A limited amount of data are also available from green tea polyphenol chemoprevention trials. Phase 1 trials of healthy volunteers have defined the basic biodistribution patterns, pharmacokinetic parameters, and preliminary safety profiles for short-term oral administration of various green tea preparations. The consumption of green tea appears to be relatively safe. Among patients with established premalignant conditions, green tea derivatives have shown potential efficacy against cervical, prostate, and hepatic malignancies without inducing major toxic effects. One novel study determined that even persons with solid tumors could safely consume up to 1 g of green tea solids, the equivalent of approximately 900 ml of green tea, three times daily. This observation supports the use of green tea for both cancer prevention and treatment (78).

Curcumin

Curcumin is one of the most extensively studied compounds isolated from dietary sources for inhibition of inflammation and cancer chemoprevention, as indicated by almost 3000 published studies. Studies from our laboratory showed that curcumin inhibited NF-κB and NF-κB-regulated gene expression in various cancer cell lines. In vitro and in vivo studies showed that this phytochemical inhibited inflammation and carcinogenesis in animal models, including breast, esophageal, stomach, and colon cancer models. Other studies showed that curcumin inhibited ulcerative proctitis and Crohn’s disease, and one showed that curcumin inhibited ulcerative colitis in humans. Another study evaluated the effect of a combination of curcumin and piperine in patients with tropical pancreatitis. One study conducted in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis showed that curcumin has a potential role in inhibiting this condition. In that study, all five patients were treated with curcumin and quercetin for a mean of 6 months and had a decreased polyp number (60.4%) and size (50.9%) from baseline with minimal adverse effects and no laboratory-determined abnormalities.

The pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic effects of oral Curcuma extract in patients with colorectal cancer have also been studied. In a study of patients with advanced colorectal cancer refractory to standard chemotherapies, 15 patients received Curcuma extract daily for up to 4 months. Results showed that oral Curcuma extract was well tolerated, and dose-limiting toxic effects were not observed. Another study showed that in patients with advanced colorectal cancer, a daily dose of 3.6 g of curcumin engendered a 62% decrease in inducible prostaglandin E2 production on day 1 and a 57% decrease on day 29 in blood samples taken 1 h after dose administration.

An early clinical trial with 62 cancer patients with external cancerous lesions at various sites (breast, 37; vulva, 4; oral, 7; skin, 7; and others, 11) reported reductions in the sense of smell (90% of patients), itching (almost all patients), lesion size and pain (10% of patients), and exudates (70% of patients) after topical application of an ointment containing curcumin. In a phase 1 clinical trial, a daily dose of 8,000 mg of curcumin taken by mouth for 3 months resulted in histologic improvement of precancerous lesions in patients with uterine cervical intraepithelial neoplasm (one of four patients), intestinal metaplasia (one of six patients), bladder cancer (one of two patients), and oral leukoplakia (two of seven patients).

Results from another study conducted by our group showed that curcumin inhibited constitutive activation of NF-κB, COX-2, and STAT3 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from the 29 multiple myeloma patients enrolled in this study. Curcumin was given in doses of 2, 4, 8, or 12 g/day orally. Treatment with curcumin was well tolerated with no adverse events. Of the 29 patients, 12 underwent treatment for 12 weeks and 5 completed 1 year of treatment with stable disease. Other studies from our group showed that curcumin inhibited pancreatic cancer. Curcumin down-regulated the expression of NF-κB, COX-2, and phosphorylated STAT3 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients (most of whom had baseline levels considerably higher than those found in healthy volunteers). These studies showed that curcumin is a potent anti-inflammatory and chemopreventive agent. A detailed description of curcumin and its anticancer properties can be found in one of our recent reviews (79).

Diallyldisulfide

Diallyldisulfide, isolated from garlic, inhibits the growth and proliferation of a number of cancer cell lines including colon, breast, glioblastoma, melanoma, and neuroblastoma cell lines. Recent studies showed that this compound induces apoptosis in Colo 320 DM human colon cancer cells by inhibiting COX-2, NF-κB, and ERK-2. It has been shown to inhibit a number of cancers including dimethylhydrazine-induced colon cancer, benzo[a]pyrene-induced neoplasia, and glutathione S-transferase activity in mice; benzo[a]pyrene-induced skin carcinogenesis in mice; N-nitrosomethylbenzylamine-induced esophageal cancer in rats; N-nitrosodiethylamine-induced forestomach neoplasia in female A/J mice; aristolochic acid-induced forestomach carcinogenesis in rats; diethylnitrosamine-induced glutathione S-transferase positive foci in rat liver; 2-amino-3-methylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoline-induced hepatocarcinogenesis in rats; and diethylnitrosamine-induced liver foci and hepatocellular adenomas in C3H mice. Diallyldisulfide has also been shown to inhibit mutagenesis or tumorigenesis induced by vinyl carbamate and N-nitrosodimethylamine; aflatoxin B1-induced and N-nitrosodiethylamine-induced liver preneoplastic foci in rats; arylamine N-acetyltransferase activity and 2-aminofluorene-DNA adducts in human promyelocytic leukemia cells; DMBA-induced mouse skin tumors; N-nitrosomethylbenzylamine-induced mutation in rat esophagus; and diethylstilbesterol-induced DNA adducts in the breasts of female ACI rats.

Diallyldisulfide is believed to bring about an anticarcinogenic effect through a number of mechanisms, such as scavenging of radicals; increasing gluathione levels; increasing the activities of enzymes such as glutathione S-transferase and catalase; inhibiting cytochrome p4502E1 and DNA repair mechanisms; and preventing chromosomal damage (80).

Thymoquinone

The chemotherapeutic and chemoprotective agents from black cumin include thymoquinone (TQ), dithymoquinone (DTQ), and thymohydroquinone, which are present in the oil of this seed. TQ has antineoplastic activity against various tumor cells. DTQ also contributes to the chemotherapeutic effects of Nigella sativa. In vitro study results indicated that DTQ and TQ are equally cytotoxic to several parental cell lines and to their corresponding multidrug-resistant human tumor cell lines. TQ induces apoptosis by p53-dependent and p53-independent pathways in cancer cell lines. It also induces cell-cycle arrest and modulates the levels of inflammatory mediators. To date, the chemotherapeutic potential of TQ has not been tested, but numerous studies have shown its promising anticancer effects in animal models. TQ suppresses carcinogen-induced forestomach and skin tumor formation in mice and acts as a chemopreventive agent at the early stage of skin tumorigenesis. Moreover, the combination of TQ and clinically used anticancer drugs has been shown to improve the drug’s therapeutic index, prevents nontumor tissues from sustaining chemotherapy-induced damage, and enhances the antitumor activity of drugs such as cisplatin and ifosfamide. A very recent report from our own group established that TQ affects the NF-κB signaling pathway by suppressing NF-κB and NF-κB-regulated gene products (81).

Capsaicin

The phenolic compound capsaicin (t8-methyl-N-vanillyl-6-nonenamide), a component of red chili, has been extensively studied. Although capsaicin has been suspected to be a carcinogen, a considerable amount of evidence suggests that it has chemopreventive effects. The antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antitumor properties of capsaicin have been established in both in vitro and in vivo systems. For example, showed that capsaicin can suppress the TPA-stimulated activation of NF-κB and AP-1 in cultured HL-60 cells. In addition, capsaicin inhibited the constitutive activation of NF-κB in malignant melanoma cells. Furthermore, capsaicin strongly suppressed the TPA-stimulated activation of NF-κB and the epidermal activation of AP-1 in mice. Another proposed mechanism of action of capsaicin is its interaction with xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes, involved in the activation and detoxification of various chemical carcinogens and mutagens. Metabolism of capsaicin by hepatic enzymes produces reactive phenoxy radical intermediates capable of binding to the active sites of enzymes and tissue macromolecules.

Capsaicin can inhibit platelet aggregation and suppress calcium-ionophore–stimulated proinflammatory responses, such as the generation of superoxide anion, phospholipase A2 activity, and membrane lipid peroxidation in macrophages. It acts as an antioxidant in various organs of laboratory animals. Anti-inflammatory properties of capsaicin against carcinogen-induced inflammation have also been reported in rats and mice. Capsaicin has exerted protective effects against ethanol-induced gastric mucosal injury, hemorrhagic erosion, lipid peroxidation, and myeloperoxidase activity in rats that was associated with suppression of COX-2. While lacking intrinsic tumor-promoting activity, capsaicin inhibited TPA-promoted mouse skin papillomagenesis (82).

Gingerol

Gingerol, a phenolic substance mainly present in the spice ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe), has diverse pharmacologic effects including antioxidant, antiapoptotic, and anti-inflammatory effects. Gingerol has been shown to have anticancer and chemopreventive properties, and the proposed mechanisms of action include the inhibition of COX-2 expression by blocking of the p38 MAPK–NF-κB signaling pathway. A detailed report on the cancer-preventive ability of gingerol was presented in a recent review by Shukla and Singh (83).

Anethole

Anethole, the principal active component of the spice fennel, has shown anticancer activity. In 1995, Al-Harbi et al. (84) studied the antitumor activity of anethole against Ehrlich ascites carcinoma induced in a tumor model in mice. The study revealed that anethole increased survival time, reduced tumor weight, and reduced the volume and body weight of the EAT-bearing mice. It also produced a significant cytotoxic effect in the EAT cells in the paw, reduced the levels of nucleic acids and MDA, and increased NP-SH concentrations.

The histopathological changes observed after treatment with anethole were comparable to those after treatment with the standard cytotoxic drug cyclophosphamide. The frequency of micronuclei occurrence and the ratio of polychromatic erythrocytes to normochromatic erythrocytes showed anethole to be mitodepressive and nonclastogenic in the femoral cells of mice. In 1996, Sen et al., (85) studied the NF-κB inhibitory activity of a derivative of anethole and anetholdithiolthione. Their study results showed that anethole inhibited H2O2, phorbol myristate acetate or TNF alpha induced NF-κB activation in human jurkat T-cells (86) studied the anticarcinogenic activity of anethole trithione against DMBA induced in a rat mammary cancer model. The study results showed that this phytochemical inhibited mammary tumor growth in a dose-dependent manner.

Nakagawa and Suzuki (87) studied the metabolism and mechanism of action of trans-anethole (anethole) and the estrogenlike activity of the compound and its metabolites in freshly isolated rat hepatocytes and cultured MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. The results suggested that the biotransformation of anethole induces a cytotoxic effect at higher concentrations in rat hepatocytes and an estrogenic effect at lower concentrations in MCF-7 cells on the basis of the concentrations of the hydroxylated intermediate, 4OHPB. Results from preclinical studies have suggested that the organosulfur compound anethole dithiolethione may be an effective chemopreventive agent against lung cancer. Lam et al, (88) conducted a phase 2b trial of anethole dithiolethione in smokers with bronchial dysplasia. The results of this clinical trial suggested that anethole dithiolethione is a potentially efficacious chemopreventive agent against lung cancer.

Diosgenin

Diosgenin, a steroidal saponin present in fenugreek, has been shown to suppress inflammation, inhibit proliferation, and induce apoptosis in various tumor cells. Research during the past decade has shown that diosgenin suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis in a wide variety of cancer cells lines. Antiproliferative effects of diosgenin are mediated through cell-cycle arrest, disruption of Ca2+ homeostasis, activation of p53, release of apoptosis-inducing factor, and modulation of caspase-3 activity. Diosgenin also inhibits azoxymethane-induced aberrant colon crypt foci, has been shown to inhibit intestinal inflammation, and modulates the activity of LOX and COX-2. Diosgenin has also been shown to bind to the chemokine receptor CXCR3, which mediates inflammatory responses. Results from our own laboratory have shown that diosgenin inhibits osteoclastogenesis, cell invasion, and cell proliferation through Akt down-regulation, IκB kinase activation, and NF-κB-regulated gene expression (89).

Eugenol

Eugenol is one of the active components of cloves. Studies conducted by Ghosh et al. (90) showed that eugenol suppressed the proliferation of melanoma cells. In a B16 xenograft study, eugenol treatment produced a significant tumor growth delay, an almost 40% decrease in tumor size, and a 19% increase in the median time to end point. Of more importance, 50% of the animals in the control group died of metastatic growth, whereas none in the eugenol treatment group showed any signs of cell invasion or metastasis. In 1994, Sukumaran et al. (91) showed that eugenol DMBA induced skin tumors in mice. The same study showed that eugenol inhibited superoxide formation and lipid peroxidation and the radical scavenging activity that may be responsible for its chemopreventive action. Studies conducted by Imaida et al. (92) showed that eugenol enhanced the development of 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-induced hyperplasia and papillomas in the forestomach but decreased the incidence of 1-methyl-1-nitrosourea-induced kidney nephroblastomas in F344 male rats.

Another study conducted by Pisano et al. (93) demonstrated that eugenol and related biphenyl (S)-6,6′-dibromo-dehydrodieugenol elicit specific antiproliferative activity on neuroectodermal tumor cells, partially triggering apoptosis. In 2003, Kim et al. (94) showed that eugenol suppresses COX-2 mRNA expression (one of the main genes implicated in the processes of inflammation and carcinogenesis) in HT-29 cells and lipopolysaccharide-stimulated mouse macrophage RAW264.7 cells. Another study by Deigner et al. (95) showed that 1′-hydroxyeugenol is a good inhibitor of 5-lipoxygenase and Cu(2+)-mediated low-density lipoprotein oxidation. The studies by Rompelberg et al. (96) showed that in vivo treatment of rats with eugenol reduced the mutagenicity of benzopyrene in the Salmonella typhimurium mutagenicity assay, whereas in vitro treatment of cultured cells with eugenol increased the genotoxicity of benzopyrene.

Wholegrain Foods

The major wholegrain foods are wheat, rice, and maize; the minor ones are barley, sorghum, millet, rye, and oats. Grains form the dietary staple for most cultures, but most are eaten as refined-grain products in Westernized countries (97). Whole grains contain chemopreventive antioxidants such as vitamin E, tocotrienols, phenolic acids, lignans, and phytic acid. The antioxidant content of whole grains is less than that of some berries but is greater than that of common fruits or vegetables (98). The refining process concentrates the carbohydrate and reduces the amount of other macronutrients, vitamins, and minerals because the outer layers are removed. In fact, all nutrients with potential preventive actions against cancer are reduced. For example, vitamin E is reduced by as much as 92% (99).

Wholegrain intake was found to reduce the risk of several cancers including those of the oral cavity, pharynx, esophagus, gallbladder, larynx, bowel, colorectum, upper digestive tract, breasts, liver, endometrium, ovaries, prostate gland, bladder, kidneys, and thyroid gland, as well as lymphomas, leukemias, and myeloma (100,101). Intake of wholegrain foods in these studies reduced the risk of cancers by 30–70% (102).

How do whole grains reduce the risk of cancer? Several potential mechanisms have been described. For instance, insoluble fibers, a major constituent of whole grains, can reduce the risk of bowel cancer (103). Additionally, insoluble fiber undergoes fermentation, thus producing short-chain fatty acids such as butyrate, which is an important suppressor of tumor formation (104). Whole grains also mediate favorable glucose response, which is protective against breast and colon cancers (105). Also, several phytochemicals from grains and pulses were reported to have chemopreventive action against a wide variety of cancers. For example, isoflavones (including daidzein, genistein, and equol) are nonsteroidal diphenolic compounds that are found in leguminous plants and have antiproliferative activities. Findings from several, but not all, studies have shown significant correlations between an isoflavone-rich soy-based diet and reduced incidence of cancer or mortality from cancer in humans. Our laboratory has shown that tocotrienols, but not tocopherols, can suppress NF-κB activation induced by most carcinogens, thus leading to suppression of various genes linked with proliferation, survival, invasion, and angiogenesis of tumors (106).

Observational studies have suggested that a diet rich in soy isoflavones (such as the typical Asian diet) is one of the most significant contributing factors for the lower observed incidence and mortality of prostate cancers in Asia. On the basis of findings about diet and of urinary excretion levels associated with daidzein, genistein, and equol in Japanese subjects compared with findings in American or European subjects, the isoflavonoids in soy products were proposed to be the agents responsible for reduced cancer risk. In addition to its effect on breast cancer, genistein and related isoflavones also inhibit cell growth or the development of chemically induced cancers in the stomach, bladder, lung, prostate, and blood (107).

Vitamins

Although controversial, the role of vitamins in cancer chemoprevention is being evaluated increasingly. Fruits and vegetables are the primary dietary sources of vitamins except for vitamin D. Vitamins, especially vitamins C, D, and E, are reported to have cancer chemopreventive activity without apparent toxicity.

Epidemiologic study findings suggest that the anticancer/chemopreventive effects of vitamin C against various types of cancers correlate with its antioxidant activities and with the inhibition of inflammation and gap junction intercellular communication. Findings from a recent epidemiologic study showed that a high vitamin C concentration in plasma had an inverse relationship with cancer-related mortality. In 1997, expert panels at the World Cancer Research Fund and the American Institute for Cancer Research estimated that vitamin C can reduce the risk of cancers of the stomach, mouth, pharynx, esophagus, lung, pancreas, and cervix (108).

The protective effects of vitamin D result from its role as a nuclear transcription factor that regulates cell growth, differentiation, apoptosis, and a wide range of cellular mechanisms central to the development of cancer (109).

Exercise/Physical Activity

There is extensive evidence suggesting that regular physical exercise may reduce the incidence of various cancers. A sedentary lifestyle has been associated with most chronic illnesses. Physical inactivity has been linked with increased risk of cancer of the breast, colon, prostate, and pancreas and of melanoma (110). The increased risk of breast cancer among sedentary women that has been shown to be due to lack of exercise has been associated with a higher serum concentration of estradiol, lower concentration of hormone-binding globulin, larger fat masses, and higher serum insulin levels. Physical inactivity can also increase the risk of colon cancer (most likely because of an increase in GI transit time, thereby increasing the duration of contact with potential carcinogens), increase the circulating levels of insulin (promote proliferation of colonic epithelial cells), alter prostaglandin levels, depress the immune function, and modify bile acid metabolism. Additionally, men with a low level of physical activity and women with a larger body mass index were more likely to have a Ki-ras mutation in their tumors, which occurs in 30–50% of colon cancers. A reduction of almost 50% in the incidence of colon cancer was observed among those with the highest levels of physical activity (111). Similarly, higher blood testosterone and IGF-1 levels and suppressed immunity due to lack of exercise may increase the incidence of prostate cancer. One study indicated that sedentary men had a 56% and women a 72% higher incidence of melanoma than did those exercising 5–7 days per week (112).

Caloric Restrictions

Fasting is a type of caloric restriction (CR) that is prescribed in most cultures. Perhaps one of the first reports that CR can influence cancer incidence was published in 1940 on the formation of skin tumors and hepatoma in mice (113, 114). Since then, several reports on this subject have been published (115, 116). Dietary restriction, especially CR, is a major modifier in experimental carcinogenesis and is known to significantly decrease the incidence of neoplasms. Gross and Dreyfuss reported that a 36% restriction in caloric intake dramatically decreased radiation-induced solid tumors and/or leukemias (117, 118). Yoshida et al. (119) also showed that CR reduces the incidence of myeloid leukemia induced by a single treatment with whole-body irradiation in mice.

How CR reduces the incidence of cancer is not fully understood. CR in rodents decreases the levels of plasma glucose and IGF-1 and postpones or attenuates cancer and inflammation without irreversible adverse effects (120). Most of the studies done on the effect of CR in rodents are long-term; however, that is not possible in humans, who routinely practice transient CR. The effect that transient CR has on cancer in humans is unclear.

CONCLUSIONS

On the basis of the studies described above, we propose a unifying hypothesis that all lifestyle factors that cause cancer (carcinogenic agents) and all agents that prevent cancer (chemopreventive agents) are linked through chronic inflammation (Fig. 10). The fact that chronic inflammation is closely linked to the tumorigenic pathway is evident from numerous lines of evidence.

First, inflammatory markers such as cytokines (such as TNF, IL-1, IL-6, and chemokines), enzymes (such as COX-2, 5-LOX, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 [MMP-9]), and adhesion molecules (such as intercellular adhesion molecule 1, endothelium leukocyte adhesion molecule 1, and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1) have been closely linked with tumorigenesis. Second, all of these inflammatory gene products have been shown to be regulated by the nuclear transcription factor, NF-κB. Third, NF-κB has been shown to control the expression of other gene products linked with tumorigenesis such as tumor cell survival or antiapoptosis (Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, IAP-1, IAP-2, XIAP, survivin, cFLIP, and TRAF-1), proliferation (such as c-myc and cyclin D1), invasion (MMP-9), and angiogenesis (vascular endothelial growth factor). Fourth, in most cancers, chronic inflammation precedes tumorigenesis.

Fifth, most carcinogens and other risk factors for cancer, including cigarette smoke, obesity, alcohol, hyperglycemia, infectious agents, sunlight, stress, food carcinogens, and environmental pollutants, have been shown to activate NF-κB. Sixth, constitutive NF-κB activation has been encountered in most types of cancers. Seventh, most chemotherapeutic agents and γ-radiation, used for the treatment of cancers, lead to activation of NF-κB. Eighth, activation of NF-κB has been linked with chemoresistance and radioresistance. Ninth, suppression of NF-κB inhibits the proliferation of tumors, leads to apoptosis, inhibits invasion, and suppresses angiogenesis. Tenth, polymorphisms of TNF, IL-1, IL-6, and cyclin D1 genes encountered in various cancers are all regulated by NF-κB. Also, mutations in genes encoding for inhibitors of NF-κB have been found in certain cancers. Eleventh, almost all chemopreventive agents described above have been shown to suppress NF-κB activation. In summary, this review outlines the preventability of cancer based on the major risk factors for cancer. The percentage of cancer-related deaths attributable to diet and tobacco is as high as 60–70% worldwide.

References

L. N. Kolonel, D. Altshuler, and B. E. Henderson. The multiethnic cohort study: exploring genes, lifestyle and cancer risk. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 4:519–27 (2004) doi:10.1038/nrc1389.

J. K. Wiencke. Impact of race/ethnicity on molecular pathways in human cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 4:79–84 (2004) doi:10.1038/nrc1257.

R. G. Ziegler, R. N. Hoover, M. C. Pike, A. Hildesheim, A. M. Nomura, D. W. West, A. H. Wu-Williams, L. N. Kolonel, P. L. Horn-Ross, J. F. Rosenthal, and M. B. Hyer. Migration patterns and breast cancer risk in Asian-American women. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 85:1819–27 (1993) doi:10.1093/jnci/85.22.1819.

W. Haenszel and M. Kurihara. Studies of Japanese migrants. I. Mortality from cancer and other diseases among Japanese in the United States. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 40:43–68 (1968).

A. S. Hamilton and T. M. Mack. Puberty and genetic susceptibility to breast cancer in a case-control study in twins. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:2313–22 (2003) doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021293.

A. Jemal, R. Siegel, E. Ward, T. Murray, J. Xu, and M. J. Thun. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J. Clin. 57:43–66 (2007).

F. Brayand, and B. Moller. Predicting the future burden of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 6:63–74 (2006) doi:10.1038/nrc1781.

P. Lichtenstein, N. V. Holm, P. K. Verkasalo, A. Iliadou, J. Kaprio, M. Koskenvuo, E. Pukkala, A. Skytthe, and K. Hemminki. Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer—analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N. Engl. J. Med. 343:78–85 (2000) doi:10.1056/NEJM200007133430201.

K. R. Loeb, and L. A. Loeb. Significance of multiple mutations in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 21:379–85 (2000) doi:10.1093/carcin/21.3.379.

W. C. Hahn, and R. A. Weinberg. Modelling the molecular circuitry of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2:331–41 (2002) doi: 10.1038/nrc795.

L. A. Mucci, S. Wedren, R. M. Tamimi, D. Trichopoulos, and H. O. Adami. The role of gene-environment interaction in the aetiology of human cancer: examples from cancers of the large bowel, lung and breast. J. Intern. Med. 249:477–93 (2001) doi:10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00839.x.

K. Czene, and K. Hemminki. Kidney cancer in the Swedish Family Cancer Database: familial risks and second primary malignancies. Kidney Int. 61:1806–13 (2002) doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00304.x.

P. Irigaray, J. A. Newby, R. Clapp, L. Hardell, V. Howard, L. Montagnier, S. Epstein, and D. Belpomme. Lifestyle-related factors and environmental agents causing cancer: an overview. Biomed. Pharmacother. 61:640–58 (2007) doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2007.10.006.

M. F. Denissenko, A. Pao, M. Tang, and G. P. Pfeifer. Preferential formation of benzo[a]pyrene adducts at lung cancer mutational hotspots in P53. Science. 274:430–2 (1996) doi:10.1126/science.274.5286.430.

R. J. Anto, A. Mukhopadhyay, S. Shishodia, C. G. Gairola, and B. B. Aggarwal. Cigarette smoke condensate activates nuclear transcription factor-kappaB through phosphorylation and degradation of IkappaB(alpha): correlation with induction of cyclooxygenase-2. Carcinogenesis. 23:1511–8 (2002) doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.9.1511.

S. Shishodiaand, and B. B. Aggarwal. Cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitor celecoxib abrogates activation of cigarette smoke-induced nuclear factor (NF)-kappaB by suppressing activation of IkappaBalpha kinase in human non-small cell lung carcinoma: correlation with suppression of cyclin D1, COX-2, and matrix metalloproteinase-9. Cancer Res. 64:5004–12 (2004) doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0206.

H. Ichikawa, Y. Nakamura, Y. Kashiwada, and B. B. Aggarwal. Anticancer drugs designed by mother nature: ancient drugs but modern targets. Curr Pharm Des. 13:3400–16 (2007) doi:10.2174/138161207782360500.

A. J. Tuyns. Epidemiology of alcohol and cancer. Cancer Res. 39:2840–3 (1979).

H. Maier, E. Sennewald, G. F. Heller, and H. Weidauer. Chronic alcohol consumption—the key risk factor for pharyngeal cancer. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 110:168–73 (1994).

H. K. Seitz, F. Stickel, and N. Homann. Pathogenetic mechanisms of upper aerodigestive tract cancer in alcoholics. Int. J. Cancer. 108:483–7 (2004) doi:10.1002/ijc.11600.

R. Doll, and R. Peto. The causes of cancer: quantitative estimates of avoidable risks of cancer in the United States today. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 66:1191–308 (1981).

R. R. Williams, and J. W. Horm. Association of cancer sites with tobacco and alcohol consumption and socioeconomic status of patients: interview study from the Third National Cancer Survey. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 58:525–47 (1977).

N. Hamajima et al. Alcohol, tobacco and breast cancer—collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 53 epidemiological studies, including 58,515 women with breast cancer and 95,067 women without the disease. Br. J. Cancer. 87:1234–45 (2002) doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600596.

M. P. Longnecker, P. A. Newcomb, R. Mittendorf, E. R. Greenberg, R. W. Clapp, G. F. Bogdan, J. Baron, B. MacMahon, and W. C. Willett. Risk of breast cancer in relation to lifetime alcohol consumption. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 87:923–9 (1995) doi:10.1093/jnci/87.12.923.

F. Stickel, D. Schuppan, E. G. Hahn, and H. K. Seitz. Cocarcinogenic effects of alcohol in hepatocarcinogenesis. Gut. 51:132–9 (2002) doi:10.1136/gut.51.1.132.

H. K. Seitz, G. Poschl, and U. A. Simanowski. Alcohol and cancer. Recent Dev Alcohol. 14:67–95 (1998) doi:10.1007/0-306-47148-5_4.

H. K. Seitz, S. Matsuzaki, A. Yokoyama, N. Homann, S. Vakevainen, and X. D. Wang. Alcohol and cancer. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 25:137S–143S (2001).

F. Donato, U. Gelatti, R. M. Limina, and G. Fattovich. Southern Europe as an example of interaction between various environmental factors: a systematic review of the epidemiologic evidence. Oncogene. 25:3756–70 (2006) doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1209557.

G. Poschl, and H. K. Seitz. Alcohol and cancer. Alcohol Alcohol. 39:155–65 (2004) doi:10.1093/alcalc/agh057.

G. Szabo, P. Mandrekar, S. Oak, and J. Mayerle. Effect of ethanol on inflammatory responses. Implications for pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 7:115–23 (2007) doi:10.1159/000104236.

B. B. Aggarwal. Nuclear factor-kappaB: the enemy within. Cancer Cell. 6:203–208 (2004) doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.003.

M. Kuratsune, S. Kohchi, and A. Horie. Carcinogenesis in the esophagus. I. Penetration of benzo(a) pyrene and other hydrocarbons into the esophageal mucosa. Gann. 56:177–87 (1965).

C. La Vecchia, A. Tavani, S. Franceschi, F. Levi, G. Corrao, and E. Negri. Epidemiology and prevention of oral cancer. Oral Oncol. 33:302–312 (1997).

P. Boffetta, M. Hashibe, C. La Vecchia, W. Zatonski, and J. Rehm. The burden of cancer attributable to alcohol drinking. Int. J. Cancer. 119:884–887 (2006) doi:10.1002/ijc.21903.

W. C. Willett. Diet and cancer. Oncologist. 5:393–404 (2000) doi:10.1634/theoncologist.5-5-393.

S. A. Bingham, R. Hughes, and A. J. Cross. Effect of white versus red meat on endogenous N-nitrosation in the human colon and further evidence of a dose response. J. Nutr. 132:3522S–3525S (2002).

A. Chao, M. J. Thun, C. J. Connell, M. L. McCullough, E. J. Jacobs, W. D. Flanders, C. Rodriguez, R. Sinha, and E. E. Calle. Meat consumption and risk of colorectal cancer. JAMA. 293:172–182 (2005) doi:10.1001/jama.293.2.172.

N. Hogg. Red meat and colon cancer: heme proteins and nitrite in the gut. A commentary on diet-induced endogenous formation of nitroso compounds in the GI tract. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 43:1037–1039 (2007) doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.07.006.

C. Rodriguez, M. L. McCullough, A. M. Mondul, E. J. Jacobs, A. Chao, A. V. Patel, M. J. Thun, and E. E. Calle. Meat consumption among Black and White men and risk of prostate cancer in the Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 15:211–216 (2006) doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0614.

R. Garcia-Closas, M. Garcia-Closas, M. Kogevinas, N. Malats, D. Silverman, C. Serra, A. Tardon, A. Carrato, G. Castano-Vinyals, M. Dosemeci, L. Moore, N. Rothman, and R. Sinha. Food, nutrient and heterocyclic amine intake and the risk of bladder cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 43:1731–1740 (2007) doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2007.05.007.

A. Tappel. Heme of consumed red meat can act as a catalyst of oxidative damage and could initiate colon, breast and prostate cancers, heart disease and other diseases. Med. Hypotheses. 68:562–4 (2007) doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2006.08.025.

L. H. O’Hanlon. High meat consumption linked to gastric-cancer risk. Lancet Oncol. 7:287 (2006) doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70638-6.

T. N. Toporcov, J. L. Antunes, and M. R. Tavares. Fat food habitual intake and risk of oral cancer. Oral Oncol. 40:925–931 (2004) doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2004.04.007.

O. Dosil-Diaz, A. Ruano-Ravina, J. J. Gestal-Otero, and J. M. Barros-Dios. Meat and fish consumption and risk of lung cancer: A case-control study in Galicia, Spain. Cancer Lett. 252:115–122 (2007) doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2006.12.008.

S. N. Lauber, and N. J. Gooderham. The cooked meat derived genotoxic carcinogen 2-amino-3-methylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine has potent hormone-like activity: mechanistic support for a role in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 67:9597–0602 (2007) doi:10.1158/0008–5472.CAN-07-1661.

D. Divisi, S. Di Tommaso, S. Salvemini, M. Garramone, and R. Crisci. Diet and cancer. Acta Biomed. 77:118–123 (2006).

Y. F. Sasaki, S. Kawaguchi, A. Kamaya, M. Ohshita, K. Kabasawa, K. Iwama, K. Taniguchi, and S. Tsuda. The comet assay with 8 mouse organs: results with 39 currently used food additives. Mutat. Res. 519:103–119 (2002).

M. Durando, L. Kass, J. Piva, C. Sonnenschein, A. M. Soto, E. H. Luque, and M. Munoz-de-Toro. Prenatal bisphenol A exposure induces preneoplastic lesions in the mammary gland in Wistar rats. Environ. Health Perspect. 115:80–6 (2007).

S. M. Ho, W. Y. Tang, J. Belmonte de Frausto, and G. S. Prins. Developmental exposure to estradiol and bisphenol A increases susceptibility to prostate carcinogenesis and epigenetically regulates phosphodiesterase type 4 variant 4. Cancer Res. 66:5624–32 (2006) doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0516.

A. Szymanska-Chabowska, J. Antonowicz-Juchniewicz, and R. Andrzejak. Some aspects of arsenic toxicity and carcinogenicity in living organism with special regard to its influence on cardiovascular system, blood and bone marrow. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health. 15:101–116 (2002).

E. E. Calle, C. Rodriguez, K. Walker-Thurmond, and M. J. Thun. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 348:1625–1638 (2003) doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021423.

A. Drewnowski, and B. M. Popkin. The nutrition transition: new trends in the global diet. Nutr. Rev. 55:31–43 (1997).

S. D. Hursting, L. M. Lashinger, L. H. Colbert, C. J. Rogers, K. W. Wheatley, N. P. Nunez, S. Mahabir, J. C. Barrett, M. R. Forman, and S. N. Perkins. Energy balance and carcinogenesis: underlying pathways and targets for intervention. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 7:484–491 (2007) doi:10.2174/156800907781386623.

A. Nareika, Y. B. Im, B. A. Game, E. H. Slate, J. J. Sanders, S. D. London, M. F. Lopes-Virella, and Y. Huang. High glucose enhances lipopolysaccharide-stimulated CD14 expression in U937 mononuclear cells by increasing nuclear factor kappaB and AP-1 activities. J. Endocrinol. 196:45–55 (2008) doi:10.1677/JOE-07-0145.

C. H. Tang, Y. C. Chiu, T. W. Tan, R. S. Yang, and W. M. Fu. Adiponectin enhances IL-6 production in human synovial fibroblast via an AdipoR1 receptor, AMPK, p38, and NF-kappa B pathway. J. Immunol. 179:5483–5492 (2007).

P. Pisani, D. M. Parkin, N. Munoz, and J. Ferlay. Cancer and infection: estimates of the attributable fraction in 1990. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 6:387–400 (1997).

D. M. Parkin. The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002. Int. J. Cancer. 118:3030–3044 (2006) doi:10.1002/ijc.21731.

S. Song, H. C. Pitot, and P. F. Lambert. The human papillomavirus type 16 E6 gene alone is sufficient to induce carcinomas in transgenic animals. J. Virol. 73:5887–5893 (1999).

B. S. Blumberg, B. Larouze, W. T. London, B. Werner, J. E. Hesser, I. Millman, G. Saimot, and M. Payet. The relation of infection with the hepatitis B agent to primary hepatic carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 81:669–682 (1975).

T. M. Hagen, S. Huang, J. Curnutte, P. Fowler, V. Martinez, C. M. Wehr, B. N. Ames, and F. V. Chisari. Extensive oxidative DNA damage in hepatocytes of transgenic mice with chronic active hepatitis destined to develop hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 91:12808–12812 (1994) doi:10.1073/pnas.91.26.12808.

A. L. Jackson, and L. A. Loeb. The contribution of endogenous sources of DNA damage to the multiple mutations in cancer. Mutat. Res. 477:7–21 (2001) doi:10.1016/S0027-5107(01)00091-4.