Abstract

The probability amplitudes for quantum entanglement, also known as Bell sates, are utilized to arrive explicitly at the identity matrix I and the \(\sigma_{x}\), \(\sigma_{y}\), and \(\sigma_{z}\) Pauli matrices, via a straight-forward \(2 \times 2\) matrix representation that utilizes the vector direct product. It is also indicated that this approach is completely equivalent to the utilization of the Kronecker product \(\otimes\) to multiply the relevant ket vectors. Furthermore, it is shown that the polarization rotation matrix R, operating on the various versions of the probability amplitude for quantum entanglement, yields four identities elegantly interconnecting these probability amplitudes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

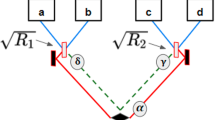

The \(\sigma_{x}\), \(\sigma_{y}\), and \(\sigma_{z}\) Pauli matrices play an important role in quantum mechanics (Feynman 1965; Landau and Lifshitz 1958) and more recently they have taken central stage in the field of quantum computing where these matrices are associated with the corresponding Pauli-X, Pauli-Y, and Pauli-Z gates (Childs 2001; Moore and Nilsson 2001). Furthermore, the mathematical function of another important gate in quantum computing, the Hadamard gate (Ekert et al. 2001), can be constructed adding two of the Pauli matrices. In addition to the matrices already mentioned, other \(2 \times 2\) matrices that interact, in optical configurations, with the probability amplitudes of quantum entanglement are the matrices corresponding to beam splitters, Mach–Zehnder interferometers, mirrors, and polarization rotators. Thus, for experimental and quantitative convenience it is important and useful to express these probability amplitudes, or Bell states, in a \(2 \times 2\) matrix format.

Already in the literature the correspondence between Bell states and the Pauli matrices has been highlighted (Dehaene et al. 2003; Sych and Leuchs 2009), albeit without explanation or derivation. Given the ubiquitous nature of beam splitters, mirrors, prisms, and polarization rotators in laboratories focused on quantum cryptography and quantum computing there is a practical need for a clear and transparent matrix-based methodology that provides a transparent explanation on the correspondence of the various Bell states and the Pauli matrices. Such straight forward mathematical development is provided here.

In addition, two sets of identities elegantly depicting the interaction of the four entangled states, \(|\psi \rangle_{ + }\), \(|\psi \rangle_{ - }\), \(|\psi \rangle^{ + }\), and \(|\psi \rangle^{ - }\) with polarization rotators and the Hadamard matrix, are given.

2 From probability amplitudes to Pauli matrices

The Pauli matrices are often introduced via the discussion of operators relevant to spin-1/2 particles (Landau and Lifshitz 1958; Robson 1974; Mandel and Wolf 1995) while Feynman introduces them, more specifically, via the Hamiltonian associated with two-state systems of such particles (Feynman 1965). An alternative avenue of introduction is via coherence matrix theory (Fano 1954; Wolf 1954; Collett 1993).

In addition to the original quantum entanglement equation (Pryce and Ward 1947; Ward 1949)

for many applications, including teleportation and quantum computing, it is convenient to express the probability amplitudes for quantum entanglement in ket vector notation as (Bennett et al. 1993)

where the \(|0\rangle\) and \(|1\rangle\) vectors can be defined as (Fowles 1968)

The vector direct product\(|x\rangle |y\rangle = |x\rangle \cdot |y\rangle^{T}\) is defined as (Ayres 1965)

For the state \(|\psi \rangle_{ + }\), defined in Eq. (2), we have

which using the vector direct product, can be expressed in matrix notation as

so that

Using the same methodology, the probability amplitude \(|\psi \rangle_{ - }\) can be expressed as

Next, the \(|\psi \rangle^{ + }\), described in Eq. (4), can be written as

so that

leading to

Finally, using the same methodology and Eq. (5) as the starting point, \(|\psi \rangle^{ - }\) can be expressed as

By inspection, the matrices given in Eqs. (11), (12), (15), and (16) can be readily identified as

These are the identity matrix I and the corresponding \(\sigma_{x}\), \(\sigma_{y}\), and \(\sigma_{z}\) Pauli matrices (Feynman et al. 1965). This observation allow us to elegantly re-express the four Bell states as

Reflection on a perfect non-polarizing mirror, represented by the identity matrix I, the various Bell states are preserved. If the entangled photons are made to be incident on a \(\pi /2\) polarization rotator, such as a half-wave plate, a Fresnel rhomb, or a broadband prism polarization rotator, all of which are represented by the matrix (Duarte 2014)

then, using the matrix methodology described here, it can readily be shown that

Once the Bell states are expressed in \(2 \times 2\) matrix form, the Hadamard matrix

can be expressed as the sum of two quantum entanglement probability amplitudes

which immediately yields its known equivalent format as the sum of two Pauli matrices

Furthermore, using the methodology described in this paper, it can be shown that

and

An important note here is that since the introduction of quantum teleportation by Bennett et al. (1993) unitary matrices have been applied to recover the original quantum state to be teleported, however, this is different to the explicit derivation of the Pauli matrices directly from the probability amplitudes describing quantum entanglement.

If the definitions for the vectors, given in Eqs. (6) and (7), are interchanged, and Eqs. (2)–(5) modified accordingly, so that the corresponding state vectors become

then, the identities given in Eqs. (21)–(24), Eqs. (26)–(29), and Eqs. (33)–(37) remain invariant thus demonstrating the mathematical consistency of this methodology.

3 From Pauli matrices to quantum entanglement

The vector–matrix process described in the previous section is completely reversible so that

thus demonstrating an additional avenue to derive the probability amplitudes applicable to a pair of quanta, propagating in opposite directions, with entangled polarizations. Assuming that the Pauli matrices are derived independently and from first principles, this simple approach adds to the heuristic derivation of Pryce and Ward (Pryce and Ward 1947; Ward 1949) and to the interferometric derivation (Duarte 2013a, b, 2014).

4 Conclusion

Here, it has been shown explicitly, using a straight forward matrix methodology, how the probability amplitudes for quantum entanglement can be used to give origin to the Pauli matrices and to the Hadamard matrix all of which are considered to be of fundamental importance in quantum computing. These results reinforce the inherent synergy between quantum entanglement physics and quantum computing. This observation might have implications on the vulnerability of cryptographic methods based quantum entanglement from the perspective of quantum computing.

The connection between the probability amplitudes for quantum entanglement, or Bell sates, and the I, \(\sigma_{x}\), \(\sigma_{y}\), \(\sigma_{z}\) matrices has been demonstrated in a straight forward fashion via the vector direct product thus adding to the tool armamentarium available to experimental physicists and engineers working on the design of quantum cryptography and quantum computing configurations. Representation of the Bell states in a transparent \(2 \times 2\) matrix form is particularly useful since polarization rotators, mirrors, and beam splitters, can all be represented in this matrix format. In this regard, examples characterizing the interaction of the four Bell states with polarization rotators, and the Hadamard matrix, are given in two corresponding sets of elegant mathematical identities.

Certainly, the method is applicable to other optical components represented by \(2 \times 2\) matrices.

Finally, since the mathematical path described here is completely reversible, the Pauli matrices themselves can be applied to arrive at the probability amplitude of quantum entanglement thus providing a third avenue of derivation to the two previously known approaches (Pryce and Ward 1947; Ward 1949; Duarte 2013a, b).

References

Ayres, F.: Modern Algebra. McGraw-Hill, New York (1965)

Bennett, C.H., Brassard, G., Crépeau, C., Jozsa, R., Peres, A., Wooters, W.A.: Teleporting an unknown quantum state via dual classical and Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 70, 1895–1899 (1993)

Childs, A.M.: Secure assisted quantum computation. Quantum Inf. Comput. 5, 456–466 (2001)

Collett, E.: Polarized Light. Marcel Dekker, New York (1993)

Dehaene, J., Van der Nest, M., De Moor, B., Verstraete, F.: Local permutations of products of Bell states and entanglement distillation. Phys. Rev. A 67, 022310 (2003)

Dirac, P.A.M.: A new notation for quantum mechanics. Math. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 35, 416–418 (1939)

Dirac, P.A.M.: The Principles of Quantum Mechanics, 4th edn. Oxford University, Oxford (1978)

Duarte, F.J.: The probability amplitude for entangled polarizations: an interferometric approach. J. Mod. Opt. 60, 1585–1587 (2013a)

Duarte, F.J.: Tunable laser optics: applications to optics and quantum optics. Prog. Quantum Electron. 37, 326–347 (2013b)

Duarte, F.J.: Quantum Optics for Engineers. CRC, New York (2014)

Ekert, A., Ericsson, M., Hayden, P., Inamori, H., Jones, J.A., Oi, D.K.L., Vedral, V.: Geometric quantum computation. J. Mod. Opt. 47, 2501–2513 (2001)

Fano, U.: A Stokes-parameter technique for the treatment of polarization in quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. 93, 121–123 (1954)

Feynman, R.P., Leighton, R.B., Sands, M.: The Feynman Lectures on Physics, vol. III. Addison-Wesley, Reading (1965)

Fowles, G.F.: Introduction to Modern Optics. Hole Rinehart Wiston, New York (1968)

Landau, L.D., Lifshitz, E.M.: Quantum Mechanics. Pergamon, New York (1958)

Magnus, J.R., Neudecker, H.: The commutation matrix: some properties and applications. Ann. Stat. 7, 381–394 (1979)

Mandel, L., Wolf, E.: Optical Coherence and Quantum Optics. Cambridge University, Cambridge (1995)

Moore, C., Nilsson, M.: Parallel quantum computation and quantum codes. SIAM J. Comput. 31, 799–815 (2001)

Neudecker, H.: Some theorems on matrix differentiation with special reference to Kronecker matrix products. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 64, 953–963 (1969)

Pryce, M.L.H., Ward, J.C.: Angular correlation effects with annihilation radiation. Nature 160, 435 (1947)

Robson, B.A.: The Theory of Polarization Phenomena. Clarendon, Oxford (1974)

Sych, D., Leuchs, G.: A complete basis of generating Bell states. New J. Phys. 11, 013006 (2009)

Ward, J.C.: Some Properties of the Elementary Particles. Oxford University, Oxford (1949)

Wolf, E.: Optics in terms of observable quantities. Nuovo Cim. 12, 884–888 (1954)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Dirac, the discovered or creator of the bra ket notation, is silent on the specific type of product to be utilized in order to perform the multiplication of two ket vectors such as \(|x\rangle |y\rangle\) (Dirac 1939, 1978). There is an enormous and obvious experimental attractiveness in expressing the probability amplitude of quantum entanglement in terms of \(2 \times 2\) matrices, which leads immediately to the use of \(|x\rangle |y\rangle = |x\rangle \cdot |y\rangle^{T}\) to multiply the ket vectors. If, instead, the Kronecker product \(\otimes\) is applied we need to use the vec function (Neudecker 1969; Magnus and Neudecker 1979) in reverse to convert the column \(4 \times 1\) vectors into \(2 \times 2\) matrices, so that

which again lead directly to the results already expressed in Eqs. (21)–(24) thus showing the complete equivalence of the two methods. In this regard, however, it is our opinion that the matrix representation utilized in the main body of this work is more compact, and direct, than the alternative tensor representation.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Duarte, F.J., Taylor, T.S. & Slaten, J.C. On the probability amplitude of quantum entanglement and the Pauli matrices. Opt Quant Electron 52, 106 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-020-2205-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-020-2205-1