Abstract

This paper empirically investigates the impacts of domestic and external factors along with exchange rate regimes (ERRs) on business cycles in a large panel of advanced and emerging market economies (EME). The results for classical business cycles suggest that EME tend to experience much deeper recessions and relatively steeper expansions during almost the same duration. The probability of expansions significantly increases with ERR flexibility. Our results strongly support floating ERR for both advanced and EME other than the East Asian countries. The impacts of external real and financial shocks and domestic variables are significantly greater under managed regimes as compared to floats. Consistent with an argument that high saving rates enhance the ability of a country to maintain an ERR, managed regimes performs better only in the East Asian countries. Supporting the de-coupling literature, external cycles become insignificant for growth under flexible ERR. Our results strongly suggest that the evolution and determinants of both classical business and growth cycles are not invariant to the prevailing ERR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It may be argued that a stationary business cycle may not be a generally accepted empirical regularity. The results by Aguiar and Gopinath (2007) suggest that, shocks to trend growth are the primary source of fluctuations in EME. In the same vein, total factor productivity (TFP), which is often taken as the main driver of business cycles, may follow a random walk process (Schmitt-Grohé and Uribe 2011).

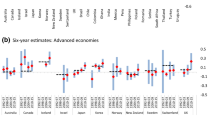

The classical cycles are computed using quarterly real GDP data which are expressed in local currency at constant prices. All quarterly real GDP series are seasonally adjusted using X-12 ARIMA method. Our sample contains 23 advanced and 27 emerging market countries as listed by Table 6. The data for real GDP are from IMF-IFS and OECD. Table 1 is based on quarterly data from 1960 to 2013 for advanced countries and post-1980 for most of the EME. For the Eastern Europe countries, we have data only after the mid 1990’s. To obtain comparable results, we consider the classical cycles of AEs also for the post-1980 sample. The results for the post-1980 sample, were essentially the same, and thus not reported to save the space. Individual country estimates are reported by an earlier version of this paper (Erdem and Özmen, 2014).

The full list of countries, including their regional and income classifications as well as the sample periods, is presented by Table 6. Note that the BBQ algorithm is unable to find turning points in the real GDP data for Iceland, Bolivia and Slovakia potentially due to the short span of the data.

The IRR data are available over the period 1946 to 2010. For the post-2010 sample the De Facto ERR classification by the IMF is used.

See Tavlas et al., (2008) for a critical review of the de facto ERR classifications. As argued by Tavlas et al., (2008, p.944), “the key distinctive characteristic of a regime is the extent to which it constraints domestic monetary policy”. Consequently, there is a need for an ERR classification based on the degree of monetary policy independence rather than relying basically on exchange rate fluctuations. The choice of de facto regimes, on the other hand, may not be independent of the de jure regimes (von Hagen and Zhou 2009).

We considered also the external financial shocks proxied by VIX. As the results are found to be essentially the same those with YC US, we prefer not to report them to save the space.

The equations for AE do not contain FF as there is indeed no episode of freely falling for them. The sample for the equations with the US cycle variable does not contain the US data.

We are grateful to an anonymous referee for raising this crucially important issue. The referee stressed the roles of the external balance and saving ratio of a given economy in its ability to maintain a given exchange rate regime.

The PARDL model is valid even if the regressors are not weakly-exogenous (Chudik and Pesaran, 2013). In an earlier version of this paper (Erdem and Özmen, 2014), the PARDL equations contained also the current values of the potentially endogenous domestic variables. The results were essentially the same with those in this paper and thus not reported to save the space.

The results are found to be essentially the same for the EME and not reported to save the space.

For our whole sample of countries, flexible ERR episodes increased from 27 % in 1960–84 to 40 % in the 1985–2013 period. Compared with the 1980–1995 period, the flexible ERR episodes increased from 33 % to 45 % for the EME sample. For the East Asian EME sample, this increase is from 20 % to 50 %. Ghosh et al., (2014) reports that the proportion of floating (independent and managed) regimes in EME has substantially increased during the recent decades.

We initially estimated (3) with the PARDL lag length chosen as 2, and by applying a sequential reduction of statistically insignificant variables, we obtained the parsimonious panel fixed effect estimation results reported by Table 5. The results tend to be robust to alternative conditioning for the domestic variables.

We are grateful to an anonymous referee for this interpretation.

References

Aguiar M, Gopinath G (2007) Emerging market business cycles: the cycle is the trend. J Polit Econ 115(1):69–102

Altug S, Canova F (2014) Do institutions and culture matter for business cycles? Open Econ Rev 25:93–122

Baxter M, Stockman A (1989) Business cycles and the exchange rate system: some international evidence. J Monet Econ 23:377–401

Benhima K (2012) Exchange rate volatility and productivity growth: the role of liability dollarization. Open Econ Rev 23:501–529

Bleaney M, Vargas LC (2009) Real exchange rates, valuation effects and growth in emerging markets. Open Econ Rev 20:631–643

Broda C (2004) Terms of trade and exchange rate regimes in developing countries. J Int Econ 63(1):31–58

Bry G, Boschan C (1971) Cyclical analysis of time series: selected procedures and computer programs. NBER, New York

Burns AF, Mitchell WC (1946) Measuring business cycles. NBER, New York

Calderón C, Fuentes JR (2014) Have business cycles changed over the last two decades? an empirical investigation. J Dev Econ 109:98–123

Calvo GA, Leiderman L, Reinhart CM (1993) Capital inflows and real exchange rate appreciation in Latin America -the role of external factors. IMF Staff Pap 40(1):108–151

Chudik, A. and M.H. Pesaran (2013) Common correlated effects estimation of heterogeneous dynamic panel data models with weakly exogenous regressors, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Globalization and Monetary Policy Institute Working Paper No. 146

Chudik, A. and M. H. Pesaran (2014) Theory and practice of GVAR modeling, working paper series 180, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas

Claessens S, Kose A, Terrones ME (2012) How do business and financial cycles interact? J Int Econ 87:178–190

Crucini MJ, Kose AM, Otrok C (2011) What are the driving forces of international business cycles? Rev Econ Dyn 14:156–175

Dellas H, Tavlas SG (2005) Mixed exchange rate systems. J Int Money Financ 24(2):243–255

Di Giovanni J, Shambaugh JC (2008) The impact of foreign interest rates on the economy: the role of the exchange rate regime. J Int Econ 74:341–361

Edwards S (2011) Exchange rates in emerging countries: eleven empirical regularities from Latin America and East Asia. Open Econ Rev 22(4):533–563

Edwards S, Levy Yeyati E (2005) Flexible exchange rates as shock absorbers. Eur Econ Rev 49(8):2079–2105

Erdem, F. and E. Özmen (2014) Exchange rate regimes and business cycles: An empirical investigation, Middle East Technical University ERC Working Paper No. 1404

Fischer S (2001) Exchange rate regimes: ıs the bipolar view correct? J Econ Perspect 15:3–24

Flood RP, Rose AK (1995) Fixing exchange rates: a virtual quest for fundamentals. J Monet Econ 36(1):3–37

Frankel JA (2005) Mundell-Fleming lecture: contractionary currency crashes in developing countries. IMF Staff Pap 55(2):149–192

Ghosh, A.R., Ostry, J.D. and M. Qureshi (2014) Exchange rate management and crisis susceptibility: A reassessment, IMF Working Papers, 14/11

Gonzalez-Rozada M, Levy-Yeyati E (2008) Global factors and emerging market spreads. Econ J 118(533):1917–1936

Harding D, Pagan A (2002) Dissecting the cycle: a methodological investigation. J Monet Econ 49:365–381

Harding D, Pagan A (2005) A suggested framework for classsifying the modes of cycle research. J Appl Econ 20:151–159

Husain AM, Mody A, Rogoff KS (2005) Exchange rate regime durability and performance in developing versus advanced economies. J Monet Econ 52:35–64

Ilzetzki, E., C. Reinhart and K.S. Rogoff (2008) Exchange rate arrangements entering the 21st Century: Which anchor will hold?, Working Paper, University of Maryland and Harvard University

Izquierdo, A., Romero, R. and E. Talvi (2008) Booms and busts in Latin America: The role of external factors, Inter-American Development Bank Working Paper 631

Kao C (1999) Spurious regression and residual-based tests for cointegration in panel data. J Econ 90:1–44

Kose A, Otrok C, Prasad ES (2012) Global business cycles: convergence or decoupling? Int Econ Rev 87:178–190

Levin A, Lin CF, Chu C (2002) Unit root tests in panel data: asymptotic and finite-sample properties. J Econ 108:1–24

Levy Yeyati E, Williams T (2012) Emerging economies in the 2000s: real decoupling and financial recoupling. J Int Money Financ 31:2102–2126

Levy-Yeyati E, Sturzenegger F (2003) To float or to fix: evidence on the impact of exchange rate regimes on growth. Am Econ Rev 93(4):1178–1189

Özatay F, Özmen E, Şahinbeyoglu G (2009) Emerging market sovereign spreads, global financial conditions and U.S. macroeconomic news. Econ Model 26:526–531

Pagan A, Robinson T (2014) Methods for assessing the impact of financial effects on business cycles in macroeconometric models. J Macroecon 41:94–106

Pedroni P (2001) Purchasing power parity tests in cointegrated panels. Rev Econ Stat 83:727–731

Perri F, Neumeyer PA (2005) Business cycles in emerging economies: the role of interest rates. J Monet Econ 52(2):345–380

Pesaran MH, Shin YC, Smith R (2001) Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J Appl Econ 16(3):289–326

Phillips PCB, Hansen B (1990) Statistical ınference in ınstrumental variables regression with I(1) processes. Rev Econ Stud 57:99–125

Rey, H. (2013) Dilemma not trilemma: The global financial cycle and monetary policy independence, Paper presented at the 25th Jackson Hole symposium, August 2013

Rose AK (2011) Exchange rate regimes in the modern era: fixed, floating, and flaky. J Econ Lit 49(3):652–672

Schmitt-Grohé S, Uribe M (2011) Business cycles with a common trend in neutral and investment-specific productivity. Rev Econ Dyn 14:122–135

Tavlas, G., Dellas, H. and A. Stockman (2008) The classification and performance of alternative exchange rate systems, European Economic Review, August, 941–63

von Hagen J, Zhou J (2009) Fear of floating and pegging: a simultaneous choice model of de jure and de facto exchange rate regimes in developing countries. Open Econ Rev 20:293–315

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We are grateful to George S. Tavlas (the Editor) and two anonymous referees for many penetrating comments and suggestions. Our paper also benefited from the contributions of Fatih Özatay, Elif Akbostancı and Kağan Parmaksız. We thank them all. The usual disclaimers apply. The views expressed in the paper are those of the authors and should not be attributed to their institutions.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Erdem, F.P., Özmen, E. Exchange Rate Regimes and Business Cycles: An Empirical Investigation. Open Econ Rev 26, 1041–1058 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-015-9361-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-015-9361-0