Abstract

Within a two-sector-two-country model of trade with aggregate scale economies and unionisation, a more generous welfare state in one country increases welfare in that country and can have positive spillover effects on the other. Furthermore, synchronised expansions of social security are more welfare enhancing than unilateral ones. Our results counter the fears that a race to the bottom in social standards may result from the ‘shrinking-tax-base’ entailed by international capital mobility. While affecting trade patterns and income distribution, capital mobility interacts with welfare state policies in increasing welfare, even when capital flows out of the country that initiates the shock.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Examining the effects of social policy on employment and growth, van der Ploeg (2003) argues that the distortion of imperfectly competitive labour markets may be corrected by social policies financed by (distortionary) progressive taxation and shows that conditional unemployment benefits may spur job creation. In Acemoglu and Shimer (2000), unemployment insurance improves allocative efficiency by enabling workers to pursue riskier and more productive options.

Existing empirical evidence reveals the importance of inter-industry connections as a source of external returns to scale in manufacturing (e.g., Caballero and Lyons 1992 and Bartelsman et al. 1994). For theoretical work on the role of vertical linkages see, for instance, Ethier (1982), Matsuyama (1995) and Venables (1996).

In de Grauwe and Polan (2005) social expenditure affects workers’ productivity by entering directly the production function of the private sector. In our model the effects of government policy on aggregate efficiency emerges endogenously and does not result from an a priori link between social transfers and productivity.

A large (small) J indicates a large (small) number of small (large) unions. For a given J, the fixed labour endowment implies that the membership of each union is constant. Hence, despite the fact that the mass of firms covered by each union varies with N, its size is constant and changes in N have no implications for the assumption of decentralised union behaviour.

Following the literature, we assume that unemployed workers from other unions cannot be employed in a given union’s sector before the latter’s unemployed members are hired.

We have assumed that unemployment benefit payments are not taxed, i.e. they are net transfers, so as to reflect a progressive income tax system. Assuming a lump-sum benefit or indexing the benefit to the after tax wage would not qualitatively alter the results.

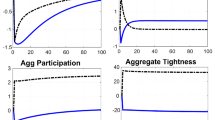

Mathematically, it can be shown that a sufficient condition for the UU to slope positively is that the unions’ monopoly power, (*), is sufficiently inelastic in L (L*). This condition—which is in line with the assumption of small unions—also ensures a trade-off in Eq. 22 between the real wage set by the unions and the employment level set by firms. It is worth noting here that the shapes of the GG and UU ensure existence and uniqueness of equilibrium, whilst the direction of arrows above and below the curves ensures stability.

The proof is not provided here but is available from the authors on request.

These results are reported in an earlier version of the paper which is available on request from the authors.

We have also examined the (t, q *) case, which is reported in an earlier version of the paper available on request from the authors.

Although with fully harmonised policy shocks there will not be any international reallocation of capital even when capital mobility is allowed for (due to the assumed symmetry between the two countries), with capital mobility the existence of the interest parity condition imposes a restriction on the adjustment of the rate of returns to capital or on the capital tax rates. As a result, the multipliers with and without capital mobility will be quantitatively different whichever instruments governments choose to use.

Interestingly, however, despite the differences in the theoretical set-up—which prevent direct comparability of the results—our conclusions are broadly consistent with those studies that pinpoint the role of social protection in determining the sectors in which a country specialises (e.g. Estevez-Abe et al. 2001, where the welfare state affects skill formation).

See, for instance, Dreher (2006).

References

Acemoglu D, Shimer R (2000) Productivity gains from unemployment insurance. Eur Econ Rev 44:1195–1224

Alesina A, Perotti R (1997) The welfare state and competitiveness. Am Econ Rev 87:921–939

Bartelsman EJ, Caballero RJ, Lyons RK (1994) Customer- and supplier-driven externalities. Am Econ Rev 84:1075–1084

Boeri T, Brugiavini A, Calmfors L (2001) The role of unions in the twenty-first century. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Caballero RJ, Lyons RK (1992) External effects in U.S. procyclical productivity. J Monet Econ 29:209–225

De Grauwe P, Polan M (2005) Globalisation and social spending. Pac Econ Rev 10:105–126

Dreher A (2006) The influence of globalisation on taxes and social policy: an empirical analysis for OECD countries. Eur J Polit Econ 22:179–201

Estevez-Abe M, Iversen T, Soskice D (2001) Social protection and formation of skills: a reinterpretation of the welfare state. In: Hall PA, Soskice D (eds) Varieties of capitalism-the institutional foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Ethier WJ (1982) National and international returns to scale in the modern theory of international trade. Am Econ Rev 72:389–405

European Commission (2002) Public finances in EMU, European economy-report and studies, 3

Garrett G (1998) Partisan politics in the global economy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Matsuyama K (1995) Complementarities and cumulative processes in models of monopolistic competition. J Econ Lit 33:701–729

Molana H, Montagna C (2006) Aggregate scale economies, market integration and optimal welfare state policy. J Int Econ 69:321–340

Ploeg van der F (2003) Do social policies harm employment and growth? CESifo working paper no. 886

Rodrik D (1997) Has globalisation gone too far? Institute for International Economics, Washington, DC

Rodrik D (1998) Why do more open economies have bigger governments. J Polit Econ 106:997–1032

Sanz I, Velázquez FJ (2003) Has the European integration approximated the composition of government expenditures? A comparative analysis between the EU and non-EU countries of the OECD. GEP research paper 2003/09, Leverhulme Centre for Globalisation and Economic Policy, School of Economics, University of Nottingham.

Venables AJ (1996) Equilibrium location of vertically linked industries. Int Econ Rev 37:341–359

Young A (1928) Increasing returns and economic progress. Econ J 38:527–542

Acknowledgement

We thank two anonymous referees and the Editor of the Journal for useful comments and suggestions. The British Academy Research Grant (Ref SG-32914) is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Molana, H., Montagna, C. Welfare State, Market Imperfections, and International Trade. Open Econ Rev 18, 95–118 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-007-9003-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-007-9003-2