Abstract

This article explores the relationship between policy narratives and the design of the Italian border management and external migration control regime in the last two decades. First, drawing from the theory of social construction and policy design and through a qualitative application of the Narrative Policy Framework, the article traces the evolution of narratives developed by key actors in government. Second, it investigates the design of the Italian externalization policy. Empirical material is drawn from government documents and decision-makers’ parliamentary interventions, press conferences, speeches, newspaper interviews and op-eds. The evidence shows that the dominant narratives have remained constant over time. Humanitarian rhetoric has been mobilized to justify and legitimize the implementation of security measures through bilateral agreements signed with African countries. The implications of such a design are relevant in that it poses serious concerns in terms of respect for migrants’ human rights. Overall, the article offers new insights into the empirical investigation of policy narratives and sheds light on the role of narratives in the social construction of migration policy design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In public policy analysis, a growing body of literature has turned to the study of narratives in the policy-making process (e.g., Fischer & Forester, 1993; Roe, 1994; van Eeten, 2007; Stone, 2012; Jones et al., 2014; Shanahan et al., 2018a, 2018b; Esposito et al., 2020). The role of narratives is intertwined with the role of ideas and knowledge in shaping public policy (Radaelli, 1995; Yee, 1996; Haas, 2004). After all, narratives represent one of the ways through which knowledge about a given policy field is disseminated (Radaelli, 1999). Narratives are indeed crucial in the articulation of certain ideas that specify how to solve policy problems. Moreover, narratives are key not only to the provision of policy solutions, but also to the very interpretation and definition of the issue to solve. As such, narratives—and the argumentations conveyed through them—constitute an important factor in the process of designing public policy (Majone, 1989).

Policy design is a process that involves ‘a deliberate endeavor to link policy tools or instruments with clearly articulated policy goals or a policy problem’ (Bali et al., 2019: 2). In this sense, a policy design is effective if it contains the most appropriate means to solve a certain policy issue and, therefore, to meet government goals (Peters et al., 2018; Bali et al., 2019; Capano & Howlett, 2021). In the field of public policy, the study of the socially constructed nature of policy design is certainly not a novelty (Ingram & Schneider, 1991; Schneider & Ingram, 1993, 1997; Ingram et al., 2007; Pierce et al., 2014). The literature on policy design also recognizes the importance of knowledge-driven capacities and information-based activities in public policy design (Capano & Howlett, 2021). However, as recently pointed out by Capano and Howlett (2020: 5–6), while scholarship has investigated ideas, frames, and beliefs systems in policy development, the literature often lacks a solid understanding of the role of actors’ normative and cognitive beliefs when policy instruments are at stake.

This article aims at sharpening existing theoretical and conceptual tools to expand our empirical understanding of the role of narratives in policy design. Investigating the relationship between narratives and policy design is particularly relevant in the field of migration, in that the development of migration policies—and the related policy instruments—often builds upon arguments that are not always grounded in evidence about cause-and-effect relationships (Cornelius & Salehyan, 2007; Heller & Pezzani, 2017; Steinhilper & Grujters, 2018; Cusumano & Villa, 2020; Zaun & Nantermoz, 2021).

Drawing from the theory of social construction and policy design and through a qualitative application of the Narrative Policy Framework (NPF), the article traces the evolution of policy narratives relating to border management and external migration controls in Italy, and it further explores the benefits of incorporating the analysis of narratives in a policy design perspective. To this aim, I investigate narratives in power, namely, those conveyed by decision-makers holding crucial governmental positions in relation to the Italian migration governance regime. In fact, as argued by Schneider and Ingram (1997: 107), ‘social constructions become central to the strategies of public officials, especially those who are in […] highly visible positions.’ In particular, I focus on Ministers of the Interior and Ministers of Foreign Affairs. Therefore, in examining how elites express their beliefs through narratives, the article intends to contribute to the study of policy-makers’ beliefs systems in relation to power (Acosta et al., 2019; Sievers & Jones, 2020).

First, this study identifies the dominant narratives and investigates whether they have changed or remained stable over time. In order to cover the whole range of official and non-official circumstances in which decision-makers express their beliefs, empirical material includes government documents and decision-makers’ parliamentary interventions, press conferences, speeches, newspaper interviews and op-eds. Second, I investigate the development and design of policy instruments. In particular, the paper focuses on bilateral agreements signed between Italy and African countries. These agreements constitute the basis upon which the Italian government has designed its strategy of border management and external migration controls.

The paper shows that the dominant narratives relating to border management and external migration controls have essentially remained the same over the past two decades. Moreover, they have cut across partisan divides and governing coalitions, and do not seem to have been connected to particular contingencies. These narratives have constantly emphasized the need to ensure a fair distribution of responsibilities (burden-sharing) between European Union (EU) Member States and to externalize border management to third countries. In particular, the article shows how a humanitarian rhetoric has been used to justify and legitimize the implementation of security measures, going however beyond the traditional argument revolving around the so-called humanitarian-security nexus (Casas-Cortes et al., 2015; Cuttitta, 2018; Sciurba & Furri, 2018). Evidence also points at the policy implications of such a design. In fact, the bilateral agreements signed between Italy and African countries are mostly concerned with domestic securitarian interests, giving little or no consideration to migrants, asylum-seekers, and refugees fundamental rights. Therefore, this study reveals the (discursive) tension between two objectives related to border management and external migration controls which go beyond this single case study. These are (i) the aim of allowing the legitimate movement of migrants seeking asylum and (ii) the aim of ensuring border security.

The article is organized as follows: Sect. 2 provides conceptual and operational definitions of policy narrative and it introduces the core elements of the NPF. The third section illustrates the case study, the methods, and the data. In Sect. 4, I analyze policy narratives over border management and external migration controls in Italy. The fifth section explores the policy instruments implemented to design the Italian externalization strategy. Finally, Sect. 6 concludes and discusses potential directions for future research.

Narratives in power and policy design: conceptual and operational definitions

The theory of social construction and policy design (Schneider & Ingram, 1993, 1997) focuses on policy-makers’ discursive abilities as well as on structural power imbalances. Social construction is the process through which values and meanings are attached to a given phenomenon, enabling interpretation and providing rationales and logics for action (Schneider & Ingram, 1997). In this respect, the notion of narratives can help disentangle the discursive, ideational, as well as power-related facets of policy design. Thus, in applying the NPF, this paper situates the empirical study of policy narratives within a social construction and policy design perspective.

The common challenge that governments face in designing border management and migration control policies relates to how to facilitate the legitimate movement of individuals while maintaining secure borders. The relationship between borders—conceived here as the boundaries of sovereign states—and security is certainly not easy to define. The concept of ‘security’ itself is notoriously difficult to conceptualize and operationalize. However, we could agree that all border control policies operate on a distinction between what Schneider and Ingram (1993, 1997) would name the ‘deservings’ and the ‘undeservings’. In this sense, these policies aim at ensuring that ‘movement deemed beneficial […] is unimpeded […] while unwanted movement […] is blocked’ (Hansen & Papademetriou, 2014: 2). According to this view, therefore, secure borders are those that are free of unauthorized and other unwanted movements of individuals. In these terms, an effective border control policy design should be able to strike a balance between migrants’ rights and border security, so that security aims do not prevent the legitimate cross-border flows of migrants seeking asylum (Terlizzi, 2019).

As argued by Schneider and Ingram (1993: 334), ‘the social construction of target populations refers to the cultural characterizations or popular images of the persons or groups whose behavior and well-being are affected by public policy.’ On the basis of the value attached to the social construction of the target groups (deserving or undeserving) and the power resources held by them (weak or strong), the authors distinguish between four types of actual or potential target populations: advantaged (strong and deserving); contenders (strong and undeserving); dependents (weak and deserving); and deviants (weak and underserving) (Schneider & Ingram, 1993, 1997). Depending on time and contexts, decision-makers can depict groups of individuals differently. For example, asylum seekers can be seen as dependents, but also as contenders or deviants. The same holds for migrants who leave their country of origin to improve their lives for reasons that are not necessarily related to the asylum seeker or refugee definitions (Pierce et al., 2014; Schneider & Ingram, 1993). The government will make policy decisions according to such different understandings and constructions of the target population. The discursive construction of target populations, therefore, influences policy instruments selection and policy design.

In targeting individuals or groups of individuals, however, policy-makers go beyond them and discursively construct the policy realities around the target population. Namely, they debate the policy issues, their causes, and their solutions with regard to a certain phenomenon—here, migration—and they do so through the strategic use of policy narratives. As noted by Roe (1994: 3), many public policy domains ‘have become so uncertain [and] complex […] that the only things left to examine are the different stories policymakers […] use to articulate and make sense of that uncertainty [and] complexity.’ These stories—or narratives—often resist change even in the presence of contradicting empirical evidence about cause-and-effect relationships concerning the debated phenomenon. In fact, one of the core assumptions of the theory of social construction and policy design is that, because rationality is bounded, actors cannot process all relevant information about complex and uncertain phenomena, and therefore rely on mental heuristics to select information. However, ‘mental heuristics filter information in a biased manner, thereby resulting in a tendency for individuals to confirm new information that is consistent with preexisting beliefs and reject information that is not’ (Pierce et al., 2014: 5).

In this respect, a policy narrative can be defined as a set of stories and arguments espoused by actors that seek to establish and stabilize, by fixing or making steady, the assumptions for public policy-making in the face of high uncertainty and complexity (Roe, 1994). Therefore, narrative stability means stability of policy beliefs systems and structures of meanings (Radaelli, 1995; Sonenshein, 2010). As such, policy-makers can strategically use narratives to shape and control policy agendas (Crow & Jones, 2018; Acosta et al., 2019; Sievers & Jones, 2020). In investigating narratives in power, the main focus of this paper is on the first, one-dimensional, and most visible expression of power, which ‘involves a focus on behavior in the making of decisions on issues over which there is an observable conflict of (subjective) interests’ (Lukes, 1974: 15). As Sievers and Jones (2020) point out, this first dimension relates to decision-making power, which can be empirically captured through the analysis of policy debates and texts.

In the literature on migration, whereas narratives have been extensively discussed (e.g., Boswell et al., 2011; Greussing & Boomgaarden, 2017; Steinhilper & Grujters, 2018; D’Amato & Lucarelli, 2019), few studies have applied the NPF (e.g., McBeth & Lybecker, 2018). In developing a research framework to study the role of narratives in migration policy-making, Boswell et al. (2011) conceptualize them as made of three components: (i) a set of claims about the policy issue to be addressed; (ii) a set of claims about the causes of the issue; and (iii) a set of claims about how the identified policy measures will solve the issue. This article relies upon this conceptualization and turns to the usefulness of the NPF in order to operationalize the key components of a policy narrative.

The NPF is a relatively new theory of the policy process that focuses on the empirical investigation of policy narratives through which actors construct policy realities. The framework was introduced as a ‘quantitative, structuralist, and positivist approach to the study and theory building of policy narratives’ (McBeth & Jones, 2010: 339). In line with a structuralist view, a policy narrative is defined as having generalizable core narrative elements. These are:

-

The setting, namely the policy problem to be addressed and its context. The context consists of facts and features characterized by a low level of contestation and that most actors in the policy area agree upon.

-

The characters, namely the victims (those who are harmed by the problem), the villains (those who are causing the problem), and the heroes (those who can potentially fix the problem). Characters can be individuals, organizations, or institutions.

-

The moral of the story, namely the promoted policy solution.

-

The plot, namely the story device that describes causal relationships between the above-defined elements of the narrative, leading from the policy problem to the solution.

Some of the core NPF’s narrative elements are connected with the three components of a policy narrative described by Boswell et al. (2011) in their conceptualization presented above. In particular, the setting identifies with the first component (a set of claims about the policy issue to be addressed), the villains relate to the second component (a set of claims about the causes of the issue), and the moral of the story recalls the third component (a set of claims about how the identified policy measures will solve the issue). Moreover, as discussed by Husmann (2015: 420), the NPF’s characters resonate Schneider and Ingram’s type of target populations. According to the author, while the advantaged (strong and deserving) could be the heroes of a policy narrative, contenders (strong and undeserving) and deviants (weak and underserving) are usually equivalent to the NPF’s villains. As for the dependents (weak and deserving), these are often seen as the victims in policy narratives.

The main advantage of the NPF consists in the fact that it provides conceptual and operational means to disaggregate the component parts of policy narratives by defining them as having specific elements that can travel across time and space to different contexts (McBeth et al., 2014; Gray & Jones, 2016; Shanahan et al., 2018a, b). Though the framework takes a structuralist and positivist position, and primarily employs quantitative methods, its origins are rooted in post-structuralism and post-positivism. Without delving into the details of ontological and epistemological debates, it is worth noting that the core ontological assumptions of the NPF reside within social constructivism. As McBeth et al., (2014: 229, 249) state, ‘although it is true that there is a reality populated by objects and processes independent of human perceptions, it is also true that the meanings of those objects and process vary in terms of how humans perceive them […]. [In this sense], the NPF posits that socially constructed realities are captured within policy narratives.’ After all, the framework builds upon post-structuralist and post-positivist scholarship concerned with the study of narratives (Stone, 1989; Fischer & Forester, 1993; Roe, 1994). That is the reason why, since its introduction, several scholars have broadened the framework arguing that the NPF is compatible with interpretivism and have therefore called for the inclusion of qualitative methods of inquiry. This article follows along this NPF’s qualitative tradition (Gray & Jones, 2016; Jones & Radaelli, 2015; Weiss, 2018).

Research design, methods, and data

The case: the Italian border management and external migration control regime

Italy represents one of the EU external borders and, given its geographical position, analyzing its migration control policy is vital to the understanding of the overall EU strategy—above all for what the Mediterranean border is concerned.

Migrants are targeted by policy-makers two times: when they are outside a country’s territory and when they are within it. In this regard, when studying migration control regimes, it is important to distinguish between the internal and external dimensions. While internal control policies are concerned with migrants who are already within a country’s territory, external control policies target migrants at the border or outside the border before their arrival (Caponio & Cappiali, 2018; Triandafyllidou & Ambrosini, 2011). Although the two dimensions are strictly intertwined, external control policies are the most relevant to study in order to investigate the design of border control policies and to assess whether a country is preventing the legitimate cross-border flows of individuals seeking asylum. The paper thus focuses on the external dimension.

Data collection and analysis

Because this paper is concerned with the analysis of narratives in power, empirical evidence is drawn from government documents by the Ministry of the Interior and the Prime Minister Office (N = 17), as well as parliamentary interventions, press conferences, speeches, newspaper interviews and op-eds by Ministers of Foreign Affairs (N = 53) and Ministers of the Interior (N = 57). The Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs are in fact the two ministries that are mostly involved in border management and external migration controls in Italy. These documents (N = 127) have been analyzed and coded in order to trace the development of policy narratives and cover a period from 2002 to 2018.Footnote 1 In order to explore the relationship between policy narratives and policy design, bilateral agreements between Italy and several African countries have been collected (N = 12). In particular, I have analyzed the content of the agreements that Italy has signed with Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Sudan, and Tunisia over the past two decades (for further details on the empirical material see ‘Appendix’).

As for the investigation of policy narratives, text data have been analyzed through qualitative content analysis using NVivo. I have systematically interpreted the material and translated all the relevant meanings in the data into categories of a coding frame. The categories have been generated by a combination of induction and deduction. A mixed inductive-deductive approach allows the researcher to move back and forth between theory and evidence, making it possible to let emerge categories from the data (data-driven) and then to group them into macro-categories deductively derived from theory (concept-driven) (Schreier, 2012; Gray & Jones, 2016; Jackson & Bazeley, 2019). The actual analysis of text data has been informed by the core NPF’s narrative elements. Following Schreier (2012), the units of coding were defined in relative terms as those parts of the material that could be interpreted in a meaningful way with respect to the coding categories. In particular, they consisted of sentences or paragraphs. The coding strategy was made of two rounds. In the first round, categories were generated inductively. In the second round of coding, those categories were grouped into macro-categories which correspond to the NPF’s elements. Therefore:

-

Text passages referring to the policy problem and its context were coded and grouped into the category setting;

-

Text passages referring to individuals, organizations, or institutions that were described as causing the policy problem were coded and grouped into the category villains.

-

Text passages referring to individuals, organizations, or institutions that were described as harmed by the policy problem were coded and grouped into the category victims.

-

Text passages referring to the promoted policy solutions were coded and grouped into the category moral of the story.

As argued by Shanahan et al., (2013: 457, emphasis added), ‘a policy narrative must contain at least one character who is cast as a hero, villain, or victim.’ As also stressed by Husmann (2015: 422), ‘although ideally policy narratives should contain all the core elements proposed by the NPF […], this is not always the case.’ In this study, the inductive analysis of the empirical material has revealed the presence of villains and victims—as well as the setting and the moral of the story. However, no text passages specifically referring to individuals or organizations designated as fixing or being able to fix the identified problem were found. In fact, whereas sentences or paragraphs mentioning decision-makers as well as national and supranational authorities to be involved in fixing the problem are present in the material, such references are vague or often overlapping with the moral of the story. Therefore, no text passage was coded as hero.

As for the plot, namely, the story device that describes causal relationships between the setting, the characters and the moral of the story (Schlaufer, 2018), no coding was conducted. The plot was instead inductively reconstructed through an in-depth analysis of the coded text extracts. Figure 1 illustrates the coding strategy.

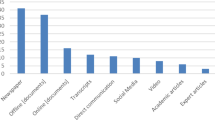

Overall, a total of 268 text passages were coded. The category that appears the most in the material is the moral of the story (56.3%), followed by the setting (18.3%), the villains (17.2%) and the victims (8.2%) (Fig. 2). In the following section, data on each category is presented and discussed in more details. As we shall see, despite changing governmental coalitions, the narrative structure along its core elements has remained stable over time.

Narrating border management and external migration controls in Italy

The setting

As shown in Fig. 3, in the last two decades, in Italy the first real watershed in terms of migration flows through the Mediterranean is 2011 with 62.692 non-EU arrivals. Following this first peak, migration flows have decreased in 2012, and then increased again to reach a second peak in 2014 (170.100 arrivals). A third peak was reached in 2016, when 181.436 non-EU nationals landed on Italian shores. However, since 2017, flows have been decreasing again. In 2018, the number dropped to 23.370 (−80.42% with respect to 2017 and −87.12% with respect to 2016). Most migrants who reached Italy departed from Libya (90% in 2016) (UNHCR, 2017). The decrease in arrivals has been mostly due to bilateral agreements signed between Italy and African countries. These agreements are part of the Italian externalization strategy that will be analyzed in the remainder of the article.

Though there has been variation in the number of arrivals, in the discourse developed by decision-makers the migratory pressure has always been considered as being high. Migratory emergency and ‘illegal’ immigrationFootnote 2 represent the policy problems to be addressed and there has been a low level of contestation about that over the whole period under consideration. In particular, ‘illegal’ immigration feature prominently in all governing coalitions except for the technocratic government (2011–2013) (Fig. 4; see also Table 1).

The villains and the victims

The EU and/or other EU Member States and the smugglers have mostly been depicted as the villains (Figs. 5 and 6). In particular, in Schneider and Ingram’s formulation, the EU and its Member States have been described as contenders, namely, as powerful actors who however do not care about the effects of their (in)action (cf. Schneider & Ingram, 1997). Instead, smugglers have been described as deviants, namely, ‘violent, threatening, and deserving to be punished’ (cf. Schneider & Ingram, 1997: 109) (Table 2).

NGOs appear in the material in 2017, when search and rescue operations provided by them have been discouraged as a result of the issue of a Code of Conduct by the Ministry of the Interior, according to which signatory NGOs enter into commitments such as that of not to enter Libyan territorial waters and not to obstruct search and rescue activities by the Libyan Coast Guard (Ministry of the Interior, 2017; Cusumano, 2019). In the debate, NGOs were targeted as contenders ‘not deserving of their exalted status’ (cf. Schneider & Ingram, 1997: 108) and contributing to the problem already in 2014, when the argument that they constitute a ‘pull factor’ for migrants to depart from African shores started to acquire force. At the EU level, this argument can be found in official documents by FRONTEX (Cusumano & Villa, 2019). Several criminal investigations against NGOs, which have been accused of favoring irregular immigration, were opened (Amnesty International, 2018). Nevertheless, as of early 2019, despite some enquiries, public prosecutors have found no evidence of crimes carried out by NGOs (Cusumano & Villa, 2020). Even the operation Mare NostrumFootnote 3 has been considered to be a contributory factor to the increase in the number of landings (Presidency of the Council of Ministers & Ministry of the Interior, 2017). However, there is no empirical evidence supporting the argument of the ‘pull factor’ (Heller & Pezzani, 2017; Steinhilper & Grujters, 2018).

Migrants and the Italian government itself have been portrayed as the victims or, in the words of Schneider and Ingram, dependents (Fig. 7). Interestingly, the Italian government has been ‘playing the victim’, describing itself as a dependent with little or no power resources (to design border management and external migration controls) and deserving help from the EU and/or other EU Member States (Table 2).

Figure 8 presents the villains and victims according to Schneider and Ingram’s categorization.

Source: Author’s elaboration based on Schneider and Ingram (1997: 109)

Social constructions of villains and victims

As we shall see, migrants are depicted as the victims within a plot that sees the smugglers as the villains and the externalization of border controls as the moral of the story. The Italian government is instead constructed as the victim within a plot where the EU and/or other EU Member States—as well as the smugglers—are the villains and EU solidarity (burden-sharing) is the moral of the story.

The moral of the story

Though it has been constantly highlighted the need to fight against ‘illegal’ immigration, in very few occasions decision-makers have pointed to the need to implement safe and legal channels for asylum seekers and refugees (Fig. 9). Legal channels for asylum seekers to access the Italian territory are guaranteed solely by the so-called humanitarian corridors (corridoi umanitari) project, which however is not a government initiative and does not receive public financing.Footnote 4 The aim is to facilitate the legal and safe arrival in Italy of potential beneficiaries—in particular the most vulnerable—of international protection (Terlizzi, 2019). Instead, emphasis has been put on the need for a fair distribution of responsibilities (burden-sharing) between EU Member States, as well as on the necessity to externalize border management and migration controls, namely, to collaborate with and provide assistance to African countries (Fig. 10, see also Table 3).

The plot(s)

In the NPF literature, it is common practice to refer to two main plot categories identified by Stone (2012): stories of decline and stories of control (see also Shanahan et al., 2013). Whereas stories of decline foster despair by telling how things are getting worse, stories of control offer hope and tell how a bad situation can be controlled and improved (Stone, 2012; see also Schlaufer, 2018). However, the two story lines are not necessarily mutually exclusive. In fact, ‘[t]he two stories are often woven together, with the story of decline serving as the stage set and the impetus for the story of control’ (Stone, 2012: 168).

Through an in-depth analysis of the coded material, I have established the relationships between the elements of the narrative that give rise to two plots. The first plot is characterized by a relationship between migratory emergency and illegal immigration (setting), EU and/or other EU Member States and smugglers (villains), the Italian government (victim), and EU solidarity (moral of the story). I have labeled this plot ‘Italy cannot be left alone’. The second plot features a relationship between migratory emergency and illegal immigration (setting), smugglers (villains), migrants (victims), and externalization (moral of the story). I have labeled this plot ‘block departures in order to save lives’. In both plots, a ‘mechanical cause’ (Shanahan et al., 2018a, b) links the setting to the moral of the story.

As already mentioned, story lines developed by decision-makers may contain elements of both decline and control (Schlaufer, 2018). In this case study, the ‘Italy cannot be left alone’ plot predominantly tells a story of decline, where decision-makers illustrate how the situation will deteriorate if the EU does not take action. Instead, the ‘block departures in order to save lives’ plot mostly tells a story of control, in which actors construct a reality out of control that can be improved if the preferred measures of externalization are implemented (cf. Schlaufer, 2018; Blum & Kuhlmann, 2019).

In particular, the ‘block departures in order to save lives’ plot shows how humanitarian rhetoric has been strategically mobilized to justify and legitimize the implementation of security measures. However, this article goes beyond the traditional argument revolving around the ‘humanitarian-security’ nexus. In fact, from an analytical point of view, a nexus would imply a point in time in which arguments about humanitarianism, which refers to those activities that are ‘intended to relieve suffering, stop preventable harm, save lives at risk, and improve the welfare of vulnerable populations’ (Barnett, 2013: 383), and securitization have been independent from one another. This has not been the case in this study, apart from few exceptions when discourses over humanitarian intervention were untied from securitization—mostly during the operation Mare Nostrum. Therefore, I would rather refer to ‘humanitarianism as securitization’ or ‘humanitarian securitization’ (Watson, 2011; Panebianco, 2016; Chouliaraki & Georgiou, 2017; Little & Vaughan-Williams, 2017; Stepka, 2018; Korkut et al., 2020). In fact, discourses about securitization identify a referent object that is threatened and endorse emergency and security measures to alleviate the threat (Watson, 2009, 2011). In the case of border management and external migration controls in Italy, the referent object has been the human life. Table 4 reports a sample of quotes that exemplifies the two identified plots.

Empirical evidence supports the claims made in the literature that stories of decline and stories of control may woven together. The two plots identified in this study are in effect not mutually exclusive. In fact, there are instances where they have run in parallel, with the ‘Italy cannot be left alone’ plot being an instrumental story of decline setting the stage for the story of control embedded in the ‘block departures in order to save lives’ plot (see e.g. Franco Frattini’s and Roberto Maroni’s exemplifying quotes in Table 4).

In the next section, I focus on the moral of the story that appears the most in the material and that is part of the ‘block departures in order to save lives’ plot, namely, externalization (see Figs. 9 and 10).

Designing externalization and securitization through bilateral agreements

The externalization of border controls is a pillar of the Italian (and EU) strategy in governing migration flows. It refers to all those ‘extraterritorial state actions to prevent migrants, including asylum seekers, from entering the legal jurisdictions or territories of destination countries’ (Frelick et al., 2016: 193). There is a wide range of actions that can be referred to as externalization measures, which include both direct actions (e.g. interdiction at the border and at sea) and indirect actions (e.g. assistance to border management policies in third countries). Externalization can occur through either bilateral and multilateral states’ agreements and initiatives or unilateral actions (Frelick et al., 2016), through which admission procedures and decisions become no longer confined to the actual physical border, but involve the point of departure—or of transit—as well (Menjívar, 2014). In a nutshell, the term externalization refers to ‘a process that moves the migration control policies beyond the external borders’ (Biondi, 2012: 149).

Externalization has always been central to the overall EU strategy in migration governance (Müller & Slominski, 2020). On November 2015, the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF) was set up by the European Commission, 25 EU Member States, Norway and Switzerland. The aim is to foster stability and contribute to better migration management, as well as ‘to address the root causes of destabilization, forced displacement and irregular migration by promoting economic and equal opportunities, security and development’ (European Commission, 2018: 7). Clearly, the objective of the Fund is to support countries of origin and transit with the aim of blocking the flow of migrants, ‘as well as to advance development projects aimed at removing the causes of migration, and to establish an African borders control system to identify transiting migrants’ (ARCI, 2016: 9). Resources currently allocated to the Fund amount to EUR 4.7 billion. EU Member States, Switzerland, and Norway have contributed around EUR 576 million. Italy is the second biggest contributor after Germany with a fund contribution that equals 21.3% (EUR 123 million) of total funding.Footnote 5 EUTF’s initiatives have been increasingly focusing on short-term security issues linked to migration. As highlighted by Barana (2017: 3–4) ‘the securitization of development and migration policy goes hand in hand with concerns about the respect for human rights […]. Examples include migrant detention centres in Libya […] or the opaque relationship between European donors and authoritarian regimes. A certain consternation has been generated by the direct budgetary support provided by Italy to Niger’s government for instance.’

In order to curb migration flows, Italy has been relying upon cooperation with African countries since the 1990s, long before the establishment of the EUTF. Agreements have been signed with Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Sudan, and Tunisia (Fig. 11).

In 1998, the first agreement between Italy and TunisiaFootnote 6 set out a bilateral cooperation to prevent and combat ‘illegal immigration.’ As stated in the agreement, ‘in view of the […] interest in supporting the efforts made by the Tunisian government in preventing and combating illegal emigration, the Italian government commits to contribute to these efforts by providing support in technical and operational means.’ Moreover, the Italian government committed to finance the establishment of detention centers in Tunisia. A commitment has also been made to provide the Tunisian police forces with means and equipment to patrol the coastline. In 1999, another agreement was signed with Algeria.Footnote 7 The need to fight against ‘illegal immigration’ was emphasized within a framework that was aimed to contrast terrorism, organized crime and drug trafficking. With this accord, the two countries undertook to exchange information on ‘illegal migration flows and the criminal organizations that favour them,’ creating space for police cooperation in the area of education and training as well as in the ‘use of the technical means employed in the fight against organized crime in all its forms.’

In 2000, two agreements were signed with Egypt and Libya.Footnote 8 While the former was concerned with the fight against organized crime and terrorism, the latter also included ‘illegal immigration’ and its content was fundamentally identical to the agreement signed with Algeria one year before. In 2003, police cooperation on ‘illegal immigration flows’ was renovated with Tunisia.Footnote 9 Another accord aimed to strengthen control in order to avoid new departures was signed with Tunisia on 6 April 2011.

Between 2007 and 2011, Italy signed three bilateral agreements with Libya. As stated in the 2007 agreement,Footnote 10 ‘given the fact that cooperation between the European Union and Libya is one of the key factors in the Global approach to the phenomenon of illegal immigration, [Italy and Libya] will intensify cooperation in the fight against criminal organizations engaged in trafficking in human beings and the exploitation of illegal immigration.’ In particular, the agreement provided for the joint maritime patrols of the Libyan coast and ‘for search and rescue operations to be carried out at the places of departure and transit, both in Libyan and international territorial waters.’ In 2011, Italy recognized Libya’s National Transitional Council (NTC) and suspended the Friendship Treaty signed with Libya in 2008.Footnote 11 A new Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the NTCFootnote 12 was signed, according to which ‘the Parties shall exchange information on flows of illegal immigration [and] on the criminal organizations that facilitate them, [as well as] provide mutual assistance and cooperation in the fight against illegal immigration, including the return of illegal immigrants.’ Bilateral agreements between the two parties have been consolidated during 2012. As a result of these agreements, Italy committed to provide the necessary technical support to help Libyan authorities to control Libya’s borders, which in turn was deemed to contribute controlling Italian borders.

In 2016, a police cooperation agreement was also reached between Italy and Sudan,Footnote 13 with the aim to prevent and combat crime in its various forms, including trafficking in persons and smuggling of migrants and irregular immigration. In particular, ‘the Parties may provide each other with advice, training and support to improve their respective capabilities in border and migration management and in combating irregular migration and related crimes.’ For its part, Italy undertook to provide technical support and assistance in terms of training and supply of means and equipment. One year later, in 2017, another MoUFootnote 14 was signed between the Italian and Libyan governments. The agreement reactivated the Treaty signed in 2008. As stated in the document, Italy reaffirms its determination to cooperate in order to find ‘urgent solutions to the issue of illegal migrants travelling through Libya to Europe by sea, through the provision of temporary reception centers in Libya, under the exclusive control of the Libyan Ministry of the Interior.’ Moreover, Italy committed to provide ‘support and funding for growth programmes in regions affected by illegal immigration, in various sectors,’ as well as technical and technological support to the Libyan Navy and the Coast Guard.

As with the 2008 treaty— and the other agreements analyzed in this section – several concerns have been raised by human rights organizations (Cuttitta, 2008, 2014; Paoletti, 2012; Palm, 2017;). As reported by Amnesty International (2018: 212), Italy has continued ‘to implement measures to increase the Libyan coastguard’s capacity to intercept refugees and migrants and take them back to Libya. This was done amidst growing evidence of the Libyan coastguard’s violent and reckless conduct during interceptions of boats and of its involvement in human rights violations.’ The MoU signed with Libya on 2017 was automatically renewed on 2 November 2019.

Discussion and conclusion

By focusing on the Italian border management and external migration control regime, the aim of this article has been to explore the relationship between policy narratives and public policy design. Drawing from the theory of social construction and policy design and through the use of qualitative NPF, the article has traced the evolution of narratives developed by actors in government. As Schneider and Ingram (1997: 110) bluntly put it, whereas ‘some social constructions are quite unstable and subject to rapid change […], [others] may remain constant over a long period of time.’ This case study has shown that, despite changing governmental coalitions, the dominant narratives have remained constant over the past two decades. In particular, policy-makers have steadily emphasized (i) the need of an effective EU solidarity (burden-sharing) and (ii) the need to externalize border controls to third countries. EU solidarity and externalization constitute the morals of the story pertaining two plots which I labeled ‘Italy cannot be left alone’ (story of decline) and ‘block departures in order to save lives’ (story of control), respectively. Evidence shows that there are instances in which the two plots have run in parallel, with the former plot being instrumental to the latter in a two-stage configuration. The ‘block departures in order to save lives’ plot shows how humanitarian rhetoric has been mobilized to justify and legitimize the implementation of security measures, going however beyond the so-called humanitarian-security nexus. Indeed, a nexus would imply a relationship between two logics which remain distinct and that conflate at some point in time. Instead, the analysis of narratives from the Italian case suggests that humanitarianism and securitization do not represent two distinct logics. These findings add to the literature in critical migration and security studies with respect to the humanitarian securitization of European borders, namely, the fusion of military border security with humanitarian benevolence (Chouliaraki & Georgiou, 2017) and its communicative and discursive aspects (Chouliaraki & Georgiou, 2017; Little & Vaughan-Williams, 2017; Stepka, 2018; Watson, 2009; Korkut et al., 2020). As argued by Chouliaraki and Georgiou (2017: 162) ‘the humanitarian aspect of bordering is here seen primarily as a technology of power that aims at ensuring survival, but not fully engaging with the humanity of mobile populations.’

Furthermore, this study has investigated the design of the Italian externalization policy. The analysis of the bilateral agreements confirmed that security objectives have outweighed human rights considerations. Border management and external migration controls constitute a public policy field that is inserted within a framework mostly designed to contrast organized crime and terrorism. The externalization policy has been sustained by a set of claims about the policy issue, the causes of the issue, and the policy solution (cf. Boswell et al., 2011) which are mostly grounded in the humanitarian ‘block departures in order to save lives’ rhetoric discussed above. The implications of such a policy design are relevant. Since cooperation is established with countries where systematic violations of human rights are reported, the externalization strategy poses serious concerns in terms of respect of migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees fundamental rights. Such a policy design is ‘dangerous’, especially in light of the possible complicity of the Italian government in the commission of internationally wrongful acts (Biondi, 2017; Mancini, 2017; ARCI, 2016, 2019a, 2019b; Liguori, 2019). Border externalization may indeed ‘attempt to (or effectively) limit formal legal obligations, including the right to seek and enjoy asylum, by preventing migrants from ever coming under the jurisdiction of destination states’ (Frelick et al., 2016: 197). Therefore, instead of striking a balance between the aim of maintaining secure borders and that of allowing the legitimate movement of individuals seeking asylum, security aims have been preventing cross-border flows of asylum-seekers.

In this respect, it should be reminded that push-back operations conducted by Italian authorities in 2009—which interdicted migrants at sea and returned them to Libya – were ruled unlawful in 2012 by the European Court of Justice in the Hirsi Jamaa v. Italy case.Footnote 15 More recently, the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights published her observations on alleged human rights violations of migrants returned from Italy to Libya, where it is recalled that Member States’ practices in the Central Mediterranean—in particular the assistance provided to the Libyan Coast Guard—have resulted in increased returns of migrants, asylum seekers and refugees to Libya, despite the fact that Member States ‘knew, or should have known, about the risk of such serious human rights violations occurring in Libya’ (Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, 2019: 9). Moreover, the Commissioner has called ‘on Council of Europe member states, in particular Italy, to urgently review all co-operation activities and practices with the Libyan Coast Guard [and urged] the suspension of any such activities until clear guarantees of full human rights compliance are in place’ (2019: 7). However, Italy is still engaged in preventing migrants to reach Italian shores and the cooperation with Libya for the purpose of border controls has not ceased.

Overall, this study brings together migration studies and policy process theory. In particular, it integrates the conceptual framework developed in the field of migration by Boswell et al. (2011) with Schneider and Ingram’s theory and the NPF, offering new insights into the empirical investigation of policy narratives. Therefore, the article has expanded the qualitative use of the NPF and integrated the research tradition that investigates the role played by narratives in migration policy-making, showing how policy narratives can be used as powerful strategic tools to influence policy design and control agendas (Crow & Jones, 2018; Acosta et al., 2019; Sievers & Jones, 2020). By focusing on Lukes (1974) first dimension of power, the article has shown that decision-makers have been insisting in implementing the same (externalization) policy that has been sustained by the same narrative through which they have stabilized the core assumptions for public policy-making in the field of border management and external migration controls.

While the analysis presented in this article has focused on decision-makers in government, a possible direction for future research would be to include actors outside government or opposition actors. For example, the inclusion of actors at the opposition would shed light on the role of dialectical confrontation in policy-making processes (Esposito et al., 2020). In this respect, the empirical analysis of narratives helps understand the power effects of persuasion, defined by Majone (1989: 8) as a ‘two-way interchange, a method of mutual learning through discourse’ in which actors promote their views of reality and adjust them as a result of the process. Because of different interpretations and ideas about a certain policy, actors—in both government and opposition—may develop different arguments thus engaging in a dialectical confrontation with the aim of ‘bringing out unstated assumptions [and] conflicting interpretations of the facts’ (Majone, 1989: 5). As also argued by Fischer (2017), the adoption of a dialectical perspective of analysis and the recognition of different points of view as essential to policy argumentation make it possible to grasp the dialectical role of conflict. It would also be interesting to further the analysis of the narratives conveyed by the same actors when they are in opposition and when they move to government (or vice versa).

I am aware of the limitations of a single case analysis and, therefore, the article intends to stimulate discussion and further comparative theoretical and empirical research on how policy narratives contribute to the social construction of policy design. For example, the analysis could be extended to other (European) countries which face similar challenges in terms of external migration controls—especially for what the management of migration flows originating from and transiting through African countries is concerned—and that have being relying upon cooperation with countries of origin and transit (e.g., Spain). Finally, further research could investigate the role of policy narratives at the intersection of external and internal migration control policies, to explore how migrants are (differently) targeted when they are at the border or outside the border of a county’s territory and when they already within it.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Notes

During this time period, alternation in government has been as follows: 2002–2006 (Berlusconi II and Berlusconi III center-right governments); 2006–2008 (Prodi II center-left government); 2008–2011 (Berlusconi IV center-right government); 2011–2013 (Monti technocratic government); 2013–2014 (Letta grand coalition government); 2014–2016 (Renzi center-left government); 2016–2018 (Gentiloni center-left government). I have collected all the parliamentary interventions, press conferences, speeches, newspaper interviews and op-eds available at the Ministries’ websites. First years available were 2002 and 2007 for the Ministry of the Interior and Ministry of Foreign Affairs, respectively. I decided not to include the Conte I government because it just took office when the data collection and analysis started.

Though since 1975 the General Assembly of the United Nations has recommended the use of the terms ‘undocumented’ or ‘irregular’ migrants, expressions such as ‘illegal’ or ‘clandestine’ are frequently found in the material (even in official documents). These terms have to be considered inappropriate both from a formal and a substantial point of view (see Liguori, 2019).

Mare Nostrum was a military and humanitarian operation launched by the Italian government on 14th October 2013 as a response to the Lampedusa shipwreck of 3 October 2013, when 368 migrants died after their boat sank before reaching Italian shores. It aimed at safeguarding human life and contrasting human traffickers and migrant smugglers. Mare Nostrum operated concurrently with Frontex and the European Border Surveillance System (EUROSUR). The operation ended on October 2014 and was replaced by the FRONTEX operation Triton and then by the EUNAVFOR MED operation Sophia.

The project was launched in 2015 with a Memorandum of Understanding between the Ministry of Foreigner Affairs, the Ministry of the Interior, the Community of Sant’Egidio, the Federation of Protestant Churches in Italy and the Waldensian Evangelical Church. The legal basis of the project rests upon Article 25 of the Regulation (EC) No 810/2009, according to which Member States can issue humanitarian visas valid for their territory.

European Commission, EU MS and Other Donors Contributions (Pledges and Received Contributions), last updated 25 February 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/content/trust-fund-financials_en.

Agreement with Tunisia, 6 August 1998 (center-left government).

Agreement with Algeria, 22 November 1999 (center-left government).

Agreement with Egypt, 18 June 2000 (center-left government). Agreement with Libya, 13 December 2000 (center-left government).

Agreement with Tunisia, 13 December 2003 (center-right government).

Agreement with Libya, 29 December 2007 (center-left government).

Agreement with Libya, 30 August 2008 (center-right government).

Agreement with Libya, 17 June 2011 (center-right government).

Agreement with Sudan, 3 August 2016 (center-left government).

Agreement with Libya, 2 February 2017 (center-left government). On similar grounds, on 9 February 2017 the Italian government (center-left) also renovated the cooperation with Tunisia.

The case is the Court’s first judgment on the interception of migrants at sea. It concerned Somali and Eritrean nationals intercepted by Italian authorities on May 6, 2009. The push-back operations were part of the government efforts aimed at interrupting the flows of migrants by sea from Libya toward Italy, and were conducted in agreement with Libyan authorities under bilateral treaties between the two states (for details see Papanicolopulu 2013).

References

Acosta, M., et al. (2019). The power of narratives: Explaining inaction on gender mainstreaming in Uganda’s climate change policy. Development Policy Review. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12458

Amnesty International. (2018). Amnesty International Report 2017/2018: The State of the World’s Human Rights. London: Amnesty International.

ARCI. (2016). Steps in the process of externalisation of border controls to Africa, from the Valletta Summit to Today. Rome: ARCI.

ARCI. (2019a). Sicurezza e Migrazione Tra Interessi Economici e Violazioni Dei Diritti Fondamentali: I Casi Di Libia, Niger Ed Egitto. Rome: ARCI.

ARCI. (2019b). The dangerous link between migration, development and security for the externalisation of borders in Africa: Case Studies on Sudan, Niger and Tunisia. ARCI.

Bali, A. S., Capano, G., & Ramesh, M. (2019). Anticipating and Designing for Policy Effectiveness. Policy and Society, 38(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2019.1579502

Barana, L. (2017). The EU trust fund for Africa and the Perils of a securitized migration policy. IAI (Istituto Affari Internationali) Commentaries, 17(31).

Barnett, M. N. (2013). Humanitarian Governance. Annual Review of Political Science, 16(1), 379–98. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-012512-083711

Biondi, P. (2012). The externalization of the EU’s Southern Border in light of the EU/Libya framework agreement: A lawful alternative or a neo-refoulement strategy? Vienna Journal on International Constitutional Law, 6(1), 144–207.

Biondi, P. (2017). The case for Italy’s complicity in Libya Push-Backs.” https://www.newsdeeply.com/refugees/community/2017/11/24/the-case-for-italys-complicity-in-libya-push-backs.

Blum, S., & Kuhlmann, J. (2019). Stories of how to give or take—towards a typology of social policy reform narratives. Policy and Society, 38(3), 339–355.

Boswell, C., Geddes, A., & Scholten, P. (2011). The Role of narratives in migration policy-making: A research framework. British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 13, 1–11.

Capano, G., & Howlett, M. (2020). The knowns and unknowns of policy instrument analysis: Policy tools and the current research Agenda on policy mixes. SAGE Open, 10(1), 215824401990056. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019900568

Capano, G., & Howlett, M. (2021). Causal logics and mechanisms in policy design: How and why adopting a mechanistic perspective can improve policy design. Public Policy and Administration, 36(2), 141–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952076719827068

Caponio, T., & Cappiali, T. M. (2018). Italian Migration Policies in Times of Crisis: The Policy Gap Reconsidered. South European Society and Politics, 23(1), 115–132.

Casas-Cortes, M., et al. (2015). New keywords: Migration and borders. Cultural Studies, 29(1), 55–87.

Chouliaraki, L., & Georgiou, M. (2017). Hospitability: The communicative architecture of humanitarian securitization at Europe’s borders. Journal of Communication, 67, 159–180.

Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights. (2019). Third Party Intervention by the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights under Article 36, Paragraph 3, of the European Convention on Human Rights: Application No. 21660/18 S.S. and Others v. Italy. Strasbourg, 15 November 2019.

Cornelius, W. A., & Salehyan, I. (2007). Does border enforcement deter unauthorized immigration? The case of Mexican migration to the United States of America. Regulation & Governance, 1(2), 139–153.

Crow, D., & Jones, M. D. (2018). Narratives as tools for influencing policy change. Policy & Politics, 46(2), 217–234.

Cusumano, E. (2019). Straightjacketing migrant rescuers? The code of conduct on maritime NGOs. Mediterranean Politics, 24(1), 106–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2017.1381400

Cusumano, E., & Villa, M. (2019). Sea rescue NGOs: A pull factor of irregular migration?. Policy Briefs; 2019/22; Migration Policy Centre.

Cusumano, E., & Villa, M. (2020). From ‘Angels’ to ‘Vice Smugglers’: The criminalization of sea rescue NGOs in Italy.” European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research.

Cuttitta, P. (2008). The case of the Italian Southern Sea Borders: Cooperation across the Mediterranean? In D. Godenau (Ed.) et al Immigration flows and the management of the EU’s Southern maritime borders. Barcelona: Documentos CIDOB.

Cuttitta, P. (2014). From the Cap Anamur to Mare Nostrum: Humaniarianism and migration controls at the EU’s maritime borders. In C. Matera and A. Taylor (Eds.) The common European Asylum system and human rights: Enhancing protection in times of emergencies. The Hague: Centre for the Law of EU External Relations, CLEER Working Papers 2014/7.

Cuttitta, P. (2018). Repoliticization through search and rescue? Humanitarian NGOs and migration management in the Central Mediterranean. Geopolitics, 23(3), 632–660. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2017.1344834

D’Amato, S., & Lucarelli, S. (2019). Talking migration: Narratives of migration and justice claims in the Euoropean Migration System of Governance. The International Spectator, 54(3), 1–17.

Esposito, G., Terlizzi, A., & Crutzen, N. (2020). Policy narratives and megaprojects: The case of the lyon-turin high-speed railway. Public Management Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1795230

European Commission. (2018). 2017 Annual Report EU Trust Fund for Africa. Publications Office of the European Union.

Fischer, F. (2017). In pursuit of usable knowledge: Critical policy analysis and the argumentative turn. In F. Fischer, D. Torgerson, A. Durnová, and M. Orsini (Eds.) Handbook of critical policy studies. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Fischer, F., & Forester, J. (Eds.). (1993). The argumentative turn in policy analysis and planning. Duke University Press.

Frelick, B., Kysel, I., & Podkul, J. (2016). The Impact of Externalization of migration controls on the rights of asylum seekers and other migrants. Journal on Migration and Human Security, 4(4), 190–220.

Gray, G., & Jones, M. D. (2016). A qualitative narrative policy framework? Examining the policy narratives of US Campaign Finance Regulatory Reform. Public Policy and Administration, 31(3), 193–220.

Greussing, E., & Boomgaarden, H. G. (2017). Shifting the refugee narrative? An automated frame analysis of Europe ’s 2015 Refugee crisis. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43(11), 1749–1774.

Haas, P. M. (2004). When does power listen to truth? A constructivist approach to the policy process. Journal of European Public Policy, 11(4), 569–592.

Hansen, R., & Papademetriou, D. G. (2014). Securing borders: The intended, unintended, and perverse consequences. Washington, D. C.: Migration Policy Institute.

Heller, C., & Pezzani, L. (2017). Blaming the rescuers. London: University of London, Goldsmiths College.

Husmann, M. A. (2015). Social constructions of obesity target population: An empirical look at obesity policy narratives. Policy Sciences, 48(4), 415–442.

Ingram, H., & Schneider, A. L. (1991). The choice of target populations. Administration & Society, 23(3), 333–356.

Ingram, H., Schneider, A. L., DeLeon, P. (2007). Social construction and policy design. In P. A. Sabatier (Ed.) Theories of the policy process. Boulder: Westview Press.

Jackson, K., & Bazeley, P. (2019). Qualitative data analysis with NVivo. SAGE.

Jones, M. D., & McBeth, M. K. (2010). A narrative policy framework: clear enough to be wrong? Policy Studies Journal, 38(2), 329–353.

Jones, M. D., & Radaelli, C. M. (2015). The narrative policy framework: Child or monster? Critical Policy Studies, 9(3), 339–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2015.1053959

Jones, M. D., Shanahan, E. A., & McBeth, M. K. (Eds.). (2014). The science of stories: applications of the narrative policy framework in public policy analysis. Palgrave Macmillan.

Korkut, U., Terlizzi, A., & Gyollai, D. (2020). Migration controls in Italy and Hungary: From conditionalized to domesticized humanitarianism at the EU Borders”. Journal of Language and Politics, 19(3), 391–412.

Liguori, A. (2019). Migration law and the externalization of border controls: European State Responsibility. Routledge.

Little, A., & Vaughan-Williams, N. (2017). Stopping boats, saving lives, securing subjects: Humanitarian Borders in Europe and Australia. European Journal of International Relations, 23(3), 533–556.

Lukes, S. (1974). Power: A radical view. Macmillan.

Majone, G. (1989). Evidence, argument, and persuasion in the policy process. Yale University Press.

Mancini, M. (2017). Italy’s new migration control policy: Stemming the flow of migrants from libya without regard for their human rights. The Italian Yearbook of International Law, 27, 259–281.

McBeth, M. K., Jones, M. D., Shanahan, E. A. (2014). The narrative policy framework. In P. A. Sabatier, C. M. Weible (Eds.) Theories of the policy process. Boulder: Westview Press.

McBeth, M. K., & Lybecker, D. L. (2018). The narrative policy framework, Agendas, and Sanctuary Cities: The construction of a public problem. Policy Studies Journal, 46(4), 868–893.

Menjívar, C. (2014). Immigration law beyond borders: externalizing and internalizing border controls in an era of securitization. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 10, 353–369.

Ministry of the Interior. (2017). Codice Di Condotta per Le ONG Impegnate Nelle Operazioni Di Salvataggio Dei Migranti in Mare. Rome: Ministry of the Interior.

Müller, P., & Slominski, P. (2020). Breaking the legal link but not the law? The externalization of EU migration control through orchestration in the Central Mediterranean. Journal of European Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1751243

Palm, Anja Valentina. 2017. “The EU External Policy on Migration and Asylum: What Role for Italy in Shaping Its Future?” Policy Brief, May 2017, Observatory on European Migration Law.

Panebianco, S. (2016). The Mediterranean Migration Crisis: Border control versus humanitarian approaches. Global Affairs, 2(4), 441–445.

Paoletti, E. (2012). Migration agreements between Italy and North Africa: Domestic imperatives versus international norms. https://www.mei.edu/publications/migration-agreements-between-italy-and-north-africa-domestic-imperatives-versus#_ftn6.

Papanicolopulu, I. (2013). Hirsi Jamaa v. Italy. The American Journal of International Law, 107(2), 417–423.

Peters, B. G., et al. (2018). Designing for policy effectiveness: Defining and understanding a concept. Cambridge University Press.

Pierce, J. J., et al. (2014). Social construction and policy design: A review of past applications. Policy Studies Journal, 42(1), 1–29.

Presidency of the Council of Ministers and Ministry of the Interior. 2017. Controllo Delle Frontiere Esterne e Gestione Dei Flussi Migratori: Verso La Revisione Dei Sistemi Triton e Dublino.

Radaelli, C. M. (1995). The role of knowledge in the policy process. Journal of European Public Policy, 2(2), 159–183.

Radaelli, C. M. (1999). Harmful tax competition in the EU: Policy narratives and advocacy coalitions. Journal of Common Market Studies, 37(4), 661–682.

Roe, E. (1994). Narrative policy analysis: Theory and practice. Duke University Press.

Schlaufer, C. (2018). The narrative uses of evidence. Policy Studies Journal, 46(1), 90–118.

Schneider, A. L., & Ingram, H. (1993). Social construction of target populations: Implications for politics and policy. American Political Science Review, 87(2), 334–347.

Schneider, A. L., & Ingram, H. (1997). Policy design for democracy. University Press of Kansas.

Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. SAGE.

Sciurba, A., & Furri, F. (2018). Human rights beyond humanitarianism: The radical challenge to the right to asylum in the Mediterranean zone. Antipode, 50(3), 763–782.

Shanahan, E. A., Jones, M. D., & McBeth, M. K. (2018a). How to conduct a narrative policy framework study. The Social Science Journal, 55(3), 332–345.

Shanahan, E. A., Jones, M. D., Mcbeth, M. K., & Lane, R. R. (2013). An angel on the wind: how heroic policy narratives shape policy realities. Policy Studies Journal, 41(3), 453–483.

Shanahan, E. A., Jones, M. D., McBeth, M. K., Radaelli, C. M. (2018). The narrative policy framework. In Weible, C. M., & Sabatier, P. A. (Eds.) Theories of the policy process. New York: Routledge.

Sievers, T., & Jones, M. D. (2020). Can power be made a viable concept in policy process theory? Exploring the power potential of the narrative policy framework. International Review of Public Policy, 2(1), 1–28.

Sonenshein, S. (2010). We’re changing-or are we? Untangling the role of progressive, regressive, and stability narratives during strategic change implementation. Academy of Management Journal, 53(3), 477–512.

Steinhilper, E., & Grujters, R. J. (2018). A Contested crisis: Policy narratives and empirical evidence on border deaths in the mediterranean. Sociology, 52(3), 515–533.

Stepka, M. (2018). Humanitarian securitization of the 2015 ‘Migration Crisis’. Investigating humanitarianism and security in the EU policy frames on operational involvement in the mediterranean. In I. Sirkec, E. L. de Freitas Castro, U. S. Sozen (Eds.) Migration policy in crisis. London: Transational Press, pp. 9–30.

Stone, D. A. (1989). Causal stories and the formation of policy Agendas. Political Science Quartely, 104(2), 281–300.

Stone, D. A. (2012). Policy paradox: The art of political decision making. W.W. Norton & Company.

Terlizzi, A. (2019). Border management and migration controls in Italy. In Global migration: Consequences and responses – respond working paper series, paper 2019/17, pp. 1–47.

Triandafyllidou, A., & Ambrosini, M. (2011). Irregular immigration control in Italy and Greece: strong fencing and weak gate-keeping serving the labour market. European Journal of Migration and Law, 13(3), 251–273.

UNHCR. 2017. Desperate journeys: refugees and migrants entering and crossing europe via the mediterranean and Western Balkans Routes. UNHCR.

van Eeten, M. J. G. (2007). Narrative policy analysis. In Fischer, F., Miller, G. J., Sidney, M. S. (Eds.) Handbook of public policy analysis. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Watson, S. (2009). The securitization of humanitarian migration: Digging moats and sinking boats. Routledge.

Watson, S. (2011). The ‘human’ as referent object? Humanitarianism as securitization. Security Dialogue, 42(1), 3–20.

Weiss, J. (2018). The evolution of reform narratives: A narrative policy framework analysis of German NPM reforms. Critical Policy Studies, pp. 1–18. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2018.1530605.

Yee, A. S. (1996). The causal effects of ideas on policies. International Organization, 50(1), 69–108.

Zaun, N., & Nantermoz, O. (2021). The use of pseudo-causal narratives in EU Policies: The case of the European Union Emergency Trust Fund for Africa. Journal of European Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1881583

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this article were presented at the 16th IMISCOE Annual Conference (Malmo University, Sweden, 26 – 28 June 2019), ECPR General Conference (University of Wroclaw, Poland, 4–7 Sept 2019), SISP Conference (University of Salento, Lecce, Italy, 12 – 14 Sept 2019), RESPOND Conference (University of Cambridge, United Kingdom, 17–19 Oct 2019). I gratefully acknowledge the helpful suggestions and criticism made by the participants. I would also like to thank Giliberto Capano, Eugenio Cusumano, Giovanni Esposito, Angela Sagnella, and the three anonymous reviewers for their valuable and constructive comments.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This research was supported by the Horizon 2020 project RESPOND—Multilevel Governance of Mass Migration in Europe and Beyond. Project Reference: 770564.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

-

1.

Government documents (coded material)

Government

Type of document

Length (pages)

Year

Center-right

Ministry of the Interior—Programmatic document

42

2006

Center-left

Ministry of the Interior—Programmatic document

47

2007

Center-left

Ministry of the Interior—Programmatic document

71

2008

Center-right

Ministry of the Interior—Programmatic document

71

2009

Center-right

Ministry of the Interior—Programmatic document

78

2010

Center-right

Ministry of the Interior—Programmatic document

92

2011

Technocratic

Ministry of the Interior—Programmatic document

111

2012

Technocratic

Ministry of the Interior—Programmatic document

145

2013

Center-left

Ministry of the Interior—Programmatic document

151

2014

Center-left

Ministry of the Interior—Programmatic document

135

2015

Center-left

Ministry of the Interior—Programmatic document

147

2016

Center-left

Non-paper (informal government document titled "Migration Compact—Contribution to an EU strategy for external action on migration")

4

2016

Center-left

Prime Minister—Letter to the Presidents of the European Commission and the European Council (letter accompanying the non-paper "Migration Compact—Contribution to an EU strategy for external action on migration")

2

2016

Center-left

Minister of the Interior—Letter to the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights

5

2017

Center-left

Ministry of the Interior—NGOs code of conduct

5

2017

Center-left

Ministry of the Interior—Programmatic document

151

2017

Center-left

Ministry of the Interior—Programmatic document

103

2018

-

2.

Parliamentary interventions, press conferences, speeches, newspaper interviews and op-eds by Ministers of Foreign Affairs (coded material)

Actor

Government

Type of document

Length (pages)

Year

Massimo D'Alema

Center-left

Parliamentary intervention

7

2007

Franco Frattini

Center-right

Parliamentary intervention

5

2008

Franco Frattini

Center-right

Parliamentary intervention

5

2008

Franco Frattini

Center-right

Press conference

3

2009

Franco Frattini

Center-right

Press conference

1

2009

Franco Frattini

Center-right

Speech (Fondazione Achille Grandi)

4

2009

Franco Frattini

Center-right

Press conference

4

2009

Franco Frattini

Center-right

Speech (University of Enna)

6

2009

Franco Frattini

Center-right

Press conference

6

2009

Franco Frattini

Center-right

Op-ed

2

2009

Franco Frattini

Center-right

Newspaper interview

2

2009

Franco Frattini

Center-right

Newspaper interview

1

2009

Franco Frattini

Center-right

Op-ed

2

2009

Franco Frattini

Center-right

Newspaper interview

2

2009

Franco Frattini

Center-right

Speech (Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe)

4

2010

Franco Frattini

Center-right

Op-ed

1

2010

Franco Frattini

Center-right

Op-ed

2

2010

Franco Frattini

Center-right

Newspaper interview

2

2011

Franco Frattini

Center-right

Newspaper interview

2

2011

Franco Frattini

Center-right

Newspaper interview

2

2011

Franco Frattini

Center-right

Newspaper interview

2

2011

Franco Frattini

Center-right

Newspaper interview

1

2011

Giulio Terzi

Technocratic

Newspaper interview

1

2011

Emma Bonino

Grand coalition

Newspaper interview

2

2013

Emma Bonino

Grand coalition

Parliamentary intervention

10

2013

Federica Mogherini

Center-left

Newspaper interview

2

2014

Federica Mogherini

Center-left

Newspaper interview

2

2014

Federica Mogherini

Center-left

Parliamentary intervention

6

2014

Federica Mogherini

Center-left

Speech (Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe)

2

2014

Paolo Gentiloni

Center-left

Parliamentary intervention

34

2014

Paolo Gentiloni

Center-left

Parliamentary intervention

3

2014

Paolo Gentiloni

Center-left

Newspaper interview

2

2015

Paolo Gentiloni

Center-left

Newspaper interview

2

2015

Paolo Gentiloni

Center-left

Newspaper interview

2

2015

Paolo Gentiloni

Center-left

Newspaper interview

2

2015

Paolo Gentiloni

Center-left

Newspaper interview

3

2015

Paolo Gentiloni

Center-left

Newspaper interview

2

2015

Paolo Gentiloni

Center-left

Op-ed

3

2015

Paolo Gentiloni

Center-left

Newspaper interview

2

2015

Paolo Gentiloni

Center-left

Newspaper interview

2

2015

Paolo Gentiloni

Center-left

Newspaper interview

2

2015

Paolo Gentiloni

Center-left

Newspaper interview

2

2015

Paolo Gentiloni

Center-left

Parliamentary intervention

66

2015

Paolo Gentiloni

Center-left

Parliamentary intervention

23

2015

Paolo Gentiloni

Center-left

Parliamentary intervention

18

2015

Paolo Gentiloni

Center-left

Parliamentary intervention

20

2015

Paolo Gentiloni

Center-left

Newspaper interview

2

2016

Paolo Gentiloni

Center-left

Op-ed

1

2016

Paolo Gentiloni

Center-left

Newspaper interview

2

2016

Angelino Alfano

Center-left

Newspaper interview

2

2017

Angelino Alfano

Center-left

Op-ed

2

2017

Angelino Alfano

Center-left

Parliamentary intervention

92

2017

Angelino Alfano

Center-left

Speech (Second Ministerial Conference “A Shared Responsibility for a Common Goal: Solidarity and Security”)

3

2018

-

3.

Parliamentary interventions, press conferences, speeches, newspaper interviews and op-eds by Ministers of the Interior (coded material)

Actor

Government

Type of document

Length (pages)

Year

Claudio Scajola

Center-right

Parliamentary intervention

3

2002

Claudio Scajola

Center-right

Press conference

1

2002

Giuseppe Pisanu

Center-right

Parliamentary intervention

6

2002

Giuseppe Pisanu

Center-right

Press conference

1

2002

Giuseppe Pisanu

Center-right

Parliamentary intervention

5

2003

Giuseppe Pisanu

Center-right

Op-ed

2

2003

Giuseppe Pisanu

Center-right

Speech (European Parliament Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs

3

2003

Giuseppe Pisanu

Center-right

Parliamentary intervention

5

2003

Giuseppe Pisanu

Center-right

Newspaper interview

2

2003

Giuseppe Pisanu

Center-right

Op-ed

2

2003

Giuseppe Pisanu

Center-right

Newspaper interview

4

2003

Giuseppe Pisanu

Center-right

Parliamentary intervention

2