Abstract

Maarten Hajer’s “Policy without polity? Policy analysis and the institutional void” (2003) was a harbinger of an age of uncertainty. Instead of a classical-modernist model, where political institutions dominate policy-making structure, regulated actors and provided clear legitimation norms, he outlined a new form of policy-making, devoid of settled norms. This essay provides a summary of the article’s impact on scholarly research over the past 14 years along three lines—ontology, processes and outcomes. In relation to the latter, which has attracted the most research efforts, it argues that recent research on the new design orientation can shed some light on why policy-making in the institutional void can lead to poor outcomes. This completes the ideational turn required by Hajer’s interpretive ambition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction: inaction under uncertainty

Maarten Hajer’s “Policy without polity? Policy analysis and the institutional void” (2003) was a harbinger of an age of uncertainty. Instead of a classical-modernist model, where political institutions dominate policy-making structure, regulated actors and provided clear legitimation norms, he outlined a new form of policy-making, within an institutional void, devoid of settled norms. Some 14 years ago, he had already started to map the rise of new actors, policy problems and epistemologies that challenge the dominance of such institutions.

This amorphous “institutional void” he sees as a natural extension of a changing world is defined by transnational networks, new technologies and the rise of civil society.

In this new modernity, the state, previously the locus and arbiter of political space and decision-making, shares the space with non-state actors, such as consumer organizations, NGOs and private companies. Contrary to what the term “institutional void” might imply, the deliberative process in the policy world described by Hajer is a highly productive one, which operates on the logic of a “double dynamic”, where actors work within the existing structure to solve policy problems while also negotiating and conceptualizing new rules and boundaries of this policy-making space.

Today, we see the pervasiveness of Hajer’s ideas, as previously authoritative policy spaces are rendered discursive, requiring a process of negotiation and deliberation through which new rules, norms and standards for policy-making are created; power no longer concentrated in the hands of the state but dispersed among a multiplicity of actors; and policy-making process increasingly less top-down and more deliberative and consultative, such that the state enters into flexible arrangements with different networks of actors based on the policy issue at hand.

Meanwhile, the state has become a facilitator or mediator in managing such processes, creating and participating in polycentric networks consisting of different actors approaching a multiplicity of policy problems. This involves a shift from the passive mode of “government” to a dynamic state of “governance”, which terms are constantly being negotiated in an act of “interactive deliberation”. While unauthorized actors may cloud or distort the process of deliberative policy-making, such “collective will formation” is the natural and inevitable outcome of our new modernity and networked society.

However, given the fact that the arena of policy-making is uncertain, and processes more diverse and fragmented, what institutions can we build to ensure that policies succeed in this new society? Hajer’s own answer was to “search for understandings of society to facilitate meaningful and legitimate political actions, agreed upon in mutual interaction, to improve our collective quality of life”.

He held three main propositions:

-

P (I) Ontology In a networked society, the policy will often be made without polity (“institutional void”).

-

P (II) Processes Such politics need new processes that will require new forms of legitimation (“democratic deficit”).

-

P (III) Outcomes Policy deliberation itself has to help defined what “improved quality of life” means for a particular choice.

Hajer’s own prediction is that “the interpretive tradition in policy analysis can take the lead” (2003: 192) in the deliberate enterprise that creates these shared understanding of society.

This essay evaluates the impact of Hajer’s article on researchers in the past 15 years, including the scholarship along the three main ideas of the institutional void, the processes of legitimation and the outcomes of policy-making under such uncertainty. It also works out the implication of these three propositions for new strands of policy theory including the literature on policy design.

In this introduction, one apparent weakness in Hajer’s ideas ought to be addressed. Hajer substantiates his idea of an emerging institutional void by using five examples—critics may argue that, with the exception of the multilateral World Trade Organization TRIPS Agreement, the examples given are centred on countries in Europe. The emergence of an institutional void outside this limited context was not addressed in the article. An argument could be made, for example, that in countries such as China and Singapore, the void does not exist and the state remains dominant in the planning and delivering of public policies. We can deal with this objection quite simply by conscribing the areas to which Hajer’s voids apply.

Further, the rising importance of non-state actors, for example, in environmental issues, the problems caused by globalization, and the rise of sustainability as an important developmental issue, after the adoption of the sustainable development goals, all give voice to the continued relevance of Hajer’s insights.

The void, legitimacy and outcomes

Since its publication in 2003, Hajer’s article has been cited nearly 900 times, including in book chapters, conference papers and journal articles. Of the latter, nearly 300 articles are captured in Web of Science. These are broadly of three types:

-

Ontology 53 articles

-

Process 49 articles

-

Outcomes 166 articles

-

Total 268

The first collection of articles refers to Hajer’s key insight on the ontologies of policy-making—of the emergence of new institutional arrangements that engage in the act of governing and governance outside and beyond the state. Here, polices are made in an “institutional void” with opaque rules and procedures, as we witness the evolution of governance models that extend beyond the state.

For example, Swyngedouw (2005) discusses how international organizations and associations such as the EU and World Bank have increasingly pioneered participatory governance arrangements as a means of fostering greater inclusiveness. These approaches have begun to challenge traditional state-centric forms of policy-making, giving substance to the idea of governance-beyond-the-state. The same author makes the point a few years later (2011) by calling these new forms the “disappearance of the political”, and the erosion of democracy and the public sphere.

A second group of articles discusses the “democratic deficit” or the new process of government within the institutional void.

For example, Bulkeley and Kern (2006) argue that addressing the challenges of climate change requires a need to focus on shaping climate protection policies at the local level. This is done through a comparative analysis of local climate policies in Germany and the UK. Instead of analysing the formal competencies of local governments, the authors focus on the possible multiple modes of governing, where municipalities are deploying self-governing and enabling approaches to undertake emissions reductions.

Hajer’s article is cited here to make the point that institutional ambiguity in these new issue areas creates complex challenges for local governments and their capacity to govern. This results in dispersed and fragmented decision-making, which warrants a new approach to governance. The writers suggest that this new approach could include processes that divest decision-making power to local authorities and municipalities for example.

Operating with such a deficit can create problems—(Schulz et al. 2017) brings this point home by arguing that in the absence of well-established rules, state actors may be inclined to cooperate disproportionately with stakeholders who are more favourable towards government policy. This “democratic deficit’ thus creates a problem for legitimation. Another dimension for legitimation arises because, in the new age of uncertainty, the role of the expert, and top-down policy-making in general have been redefined, leading to new voices in governance.

Take the example of science and innovation. Stilgoe points out that over the last two decades, particularly in Northern Europe, new deliberative forums on issues involving science and innovation have been established, moving beyond engagement with stakeholders to include members of the wider public (e.g. RCEP 1998; Grove-White et al. 1997; Wilsdon and Willis 2004; Stirling 2006). These small-group processes include consensus conferences, citizens’ juries, deliberative mapping, deliberative polling and focus groups (see Chilvers 2010).

A third set of articles is foreshadowed by the first two—the outcomes of policy-making under these new forms. Here, the articles divide into two—authors such as Measham et al. (2011) point out the suboptimal outcomes that can come about as a result of the institutional void. Examining the case of municipal planning and adaptation in three municipalities Sydney, Australia, they argue that such uncertainty in policy-making can lead to poor implementation.

The results of their study revealed that while climate change adaptation was widely accepted as an important issue by the local governments, it was yet to be embedded in municipal planning practice, which retained a strong mitigation (i.e. status quo) bias in relation to climate change. The writers argue that local municipal planning can play a greater role in achieving successful climate adaptation. However, they operate within an “institutional void” where ineffectual policies are developed as a result of the absence of clear definitions of institutional roles and responsibilities.

While the majority of the articles on outcomes show the poor quality of decisions that tend to emanate within the institutional void (Heazle and Kane 2016; Gandy 2017), others are more neutral, arguing that the outcomes are contingent on several factors, including the choice of regulations and the norms which underpin these. Jack Stilgoe et al. (2013), for example, argue that responsible innovation could take place under this institutional void—even as we move from old, traditional models of governance to more decentralized and open-ended models, we can make use of new actors and institutions beyond the conventional realm of policy and politics markets, networks and partnerships.

S/N | Article | Variable type | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

1. | Swyngedouw (2005) | Ontology | The author focuses on the fifth dimension of social innovation—political governance. He argues that innovative governance arrangements are being increasingly recognized as a means of fostering inclusive development processes. Hajer’s paper is cited several times as tracing the emergence of new institutional arrangements that engage in the act of governing and governance outside and beyond the state, i.e. governance mechanisms as operating in an “institutional void” |

2. | Huitema et al. (2009) | Process | A literature review of water governance literature to assess the institutional prescriptions of adaptive co-management Hajer’s paper is cited with reference to the “classical modernist” approach to institutional design, which emphasizes the mutual exclusivity of jurisdictions and remains popular in governance practice |

3. | Measham et al. (2011) | Outcomes | The authors argue that there is a need to focus on a wider set of constraints to municipal planning, to ensure adaptation. Adaptation may operate within an “institutional void” where ineffectual policies are developed as a result of the absence of clear definitions of institutional roles and responsibilities |

4. | Stilgoe et al. (2013) | Outcomes | The authors advocate a framework aimed at “responsible innovation”, given that the governance of emerging science and innovation is likely to pose a major challenge for democracies. The paper is on the controversial subject of geoengineering. Hajer’s paper is cited for the argument that emerging technologies typically fall into an “institutional void” with few agreed structures or rules to govern them |

5. | Schulz et al. (2017) | Process | The authors seek to develop a theoretical foundation for investigating the role of values in water governance. Hajer’s article is cited for the criticisms against environmental governance. Premised on the “democratic deficit”; state actors may be inclined to cooperate disproportionately with stakeholders who are more favourable towards government policy |

6. | Bulkeley and Kern (2006) | Process | The authors argue that addressing the challenges of climate change requires shaping climate protection policies at the local level. Hajer’s article is cited here for the point that institutional ambiguity in new issue areas, such as climate protection and sustainable development, is creating complex challenges for local governments in their capacity to govern. This results in fragmented decision-making. |

7. | Skelcher et al. (2005) | Ontology | In this article, the authors focus on the relationship between democratic practices and the design of institutions operating in collaborative spaces, where multiple public, private and non-profit actors work together to shape, make and implement public policy. The authors argue that while such partnerships offer flexibility and stakeholder engagement, they are loosely coupled to representative democratic systems |

8. | Perkins (2006) | Ontology | The author discusses the emergence of a de-centred and privatized mode of governance in the Canadian forest sector Hajer’s article is cited to support the argument that social and political theory has taken a deliberative turn, with a sustained interest in the weakening of constitutional and classical institutional politics, and a strengthening of new political spaces and network styles of governance |

9. | Gandy (2017) | Outcomes (negative) | Current approaches to the study of light do not capture the full complexity of the politics of light under late modernity. Policy responses are ineffective, inconsistent and outmoded because of the different regulatory landscapes—i.e. within the “institutional void” |

10. | Craft et al. (2017) | Outcomes (contingent) | This paper points out that the “first wave” approaches of advisory system are limited and we need to move towards a second wave, which reorients the unit of analysis away from the public service to the nature of advisory activity itself Context not only is a domain-specific matter but also applies to the very nature of problem definition and consensus formation |

11. | Heazle (2016) | Outcomes (Negative) | This chapter examines the estrangement of expert authority in the IWC, despite the strong role given to it by the commission’s founding convention. The IWC is an example of how high and sustained levels of political conflict can prolong policy deadlock within an institutional void over several decades, leading ultimately, perhaps, to institutional failure and collapse |

Still, the question of poor outcomes demands an answer. What are the determinants of outcomes of the institutional void? Why do so many researchers find poor policy decisions to be made under this void?

Ambiguity, complexity and non-design

One explanation can be given in the light of an emerging strand of literature on a new orientation in policy design which provides specifically for instances of policy-making under uncertainty or where there is a lack of settled norms.

Policy design within the traditional policy sciences has a purposeful, linear (or instrumental) character. Howlett et al. (2015: 4) outlines this as: “policy design as a specific kind of policy-making in which knowledge of the impact of specific policy tools was combined with the practical capacity of governments to identify and implement the most suitable technical means in the effort to achieve a specific policy aim”, or a “classical” form in Hajerian terms. This follows Lasswell’s original concept of the policy process, where policy design was a rational process, informed by knowledge of policy tools and instruments, and separate from the messier, more contingent process of decision-making and implementation (Lasswell 1951).

In recent years, given the increasing complexities and ambiguities, especially in socio-ecological policies, there has been recognition of a distinct new orientation within policy thinking called “new policy design”. It has a more complex conception of tools—with policy planning seen as a mix of multiple goals and instruments (Chapman 2003; Givoni and Banister 2012). It also pays greater attention to the path dependencies (Howlett et al. 2016), recognizing that patching and packaging—sub-optional planning and design activities—do occur.

The rise of this new orientation on policy design can also be traced to Hajer’s predictions, including the stronger influence of non-state actors (Howlett and Lejano 2013), and the proliferation of ideas in governance studies, or what has been called the “globalization and governance turn” (Howlett et al. 2015).

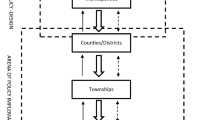

The new design orientation is depicted in the figure below (Fig. 1).

Q4, although relatively under-researched, has given some ideas on what policy-making within the institutional void can look like. First, it is more like Hajer’s modernity model than the classical policy institutional model—political interests, bargaining or other forms of satisficing behaviour which characterize alternative generation of policies here (Sidney 2007; Bendor et al. 2009). These are termed “non-design” by Howlett and Mukherjee (2014).

Second, it is the result of satisficing—a less than optimal equilibrium created by a non-rational (not to say irrational) process of formulation. This contrasts with the Lasswellian Platonic form of design in Q1, where there is both high intention to create policies and high government capacity. In this space, “only poorly informed, non-design is possible” (Howlett et al. 2015).

Using Hajer’s institutional void, where norms are unclear, and context is highly uncertain, it is not unexpected that there is a lack of policy design. Not unsurprisingly, the space is filled with the sort of policies postulated (poorly informed), or dynamics of the sort that is engendered by self-interest (venal, corrupting, political gain and blame avoidance) (Table 1).

We have an explanation therefore about why poor outcomes tend to obtain.

A related question therefore is—what is the logic behind this space? Because, as we have seen, Hajer’s conception also allows for good outcomes to take place even in an institutional void, depending on the negotiated outcomes among the different actors involved in the deliberations. Howlett (2015) himself suggests that there is a crucial role of ideas in this new design orientation.

In lieu of a conclusion, I suggest that one answer can be found in the literature on interpretive policy analysis, where Hajer ended his explorations—that policy-making within the institutional void holds a special place for narratives and interpretations; further, that such narratives form important legitimation devices for policy-making under the uncertainty of institutional voids.

In Lieu of conclusion: completing Hajer’s ideational turn

Hajer hints at the importance of interpretation, along with a post-positivism conception of knowledge, in his original paper where he notes that the role of knowledge has changed with changing policy context—rather than being accepted, knowledge was becomingly increasingly negotiated, a view in line with the “interpretive turn” of social sciences in the late 1970s and 1980s (Rabinow and Sullivan 1979, 1987).

This was soon followed by those who argued for a hermeneutic approach to social sciences, including those who like Hajer argue that information is transformed in both its production and its use, that is to say, the social nature of reality (Guba and Lincoln 1994; Lin 1998).

In this construction and interpretation of social reality, the role of narratives is crucial. Roe (1989, 1994) shows how narratives allow people to understand policy issues, especially when such issues appear intractable, complex and run the risk of polarizing different stakeholders. The “ability of public managers to tell a good story about a policy issue”, he says, is directly related to how they are perceived to manage such issues (1989: 267).

What then is a good story?

This is an important question because the ability of a narrative to move communities to collective action has been foreshadowed in what Hajer calls “collective will formation”. If, as he argues, policy deliberation is a central “site” of politics, policy initiatives therefore are platforms for people to reflect on their identities and decide collectively what they want to achieve (2003:190). He acknowledges, however, that there is very little known about how successful mediations take place, or the legitimation processes that undergird such efforts.

Theories of policy narratives can provide some answers. For example, Roe argues that a good story is a meta-narrative (1994) that can “embrace” major and opposing viewpoints on an issue. Such meta-narratives enable the decision-maker to form a set of stable assumptions and allow him to make a decision, rather than being paralysed by conflicting narratives. In this, we see the first path of legitimation.

A second path is provided by the fact that narrative formations are an important element of deliberative democracy. Writing about environmental policy analysis, Hampton shows that narrative analysis allows public participation, which “is at the heart of deliberative democracy” as such participation is “how public preferences are given due consideration” (2009: 227). Public narratives are therefore proxies for how members of the public perceive their key interests and taking these into account is important as a legitimation pathway.

Third, also outlined by Hampton, narratives have a moral component, an argument also reflected in the work of Stone (1989) and Fischer (2003). As Fischer points out, narratives are by nature normatively constituted. “Storylines are not just about a given reality. While they typically give coalition members a normative orientation to a particular reality, they are as much about changing reality as they are about simply understanding or affirming it.” Such constructed reality is not a “given” but a normatively constituted. The performative aspect of narrative—i.e. a change in narrative may effect a change in policy—also illustrates Hajer’s “double dynamic” by reflecting what the public perceive to be “right” or “just”.

These three legitimation pathways then allow us to see how policy-making can be more or less legitimate within an institutional void. Policy texts do not exist as stand-alone entities, but must be interpreted in relation to other objects, actors and texts in which it is found.

Ricoeur notes that right understanding can no longer be solved by a simple return to the alleged intention of the author (1973) but must be construed by a process. For Fischer, a collection of such understandings qualifies as “knowledge” which he thinks ought to be expanded “beyond the narrow confines of observational statements and logical proof to include an understanding of the ways people are embedded in the wider social contexts of situation and society” (Fischer 2003). Within an institutional void then, interpretation of text, discourses and narratives provide legitimation pathways for policy-making and analyses.

This completes Hajer’s ideational turn and allows us to see collective will formation as the construction of policy narratives within the broader context of sociopolitical setting and events. In this void, actors behave according to a “logic of social appropriateness” rather than the “logic of instrumentality” postulated by the classical form of policy-making (Campbell 1995 as cited in Hall and Taylor 1996).

In Hajer’s late modernity, a diversity of institutional forms is possible in any given situation; choosing from among them will require picking the one which is best constructed to meet the needs (whether defined as interests or norms or histories) of the community. Understanding policy change and policy-making within the void therefore requires us to take a deeply interpretive approach.

What does such an approach look like?

A concrete example can be seen in work on “pockets” of effective agencies, inter alia Daland (1981), Leonard (2010) and Strauss (1998). Foremost among these is Elinor Ostrom under the lens of polycentric governance. Under this framework, she argues, there are many centres of legitimacy, each of which provides stability and justification for a system of governance. Her empirical demonstrations are that collective action under such polycentricity can sometimes be successful, in fact more successful than government intervention and external sanctions. While her work is important and has routed the simplistic model of an economic actor as a rational, critics have argued against the complexity of her models (Ostrom 2005: 175).

However, as this essay has shown, such complexity is not only empirically more faithful given the emergence of new ontologies of policy-making, but it also allows us a better understanding of the processes of change in multiple settings. Depending on how we construct, legitimate and include (or exclude) communities into such narratives, what Hajer calls “collective will formation”, we can determine to some extent, the legitimacy of policy-making, and hence its likely outcome within the context of an institutional void. The author gratefully acknowledges the research assistance of Nisha Francine Rajoo, Ng Yihang, Zheng Lulu, Zhou Yishou and Victor Augusto Fernandez in documenting and coding more than 200 journal articles.

References

Bendor, J., Kumar, S., & Siegel, D. (2009). Satisficing: A ‘pretty good’ heuristic. The B.E. Journal of Theoretical Economics, 9(1), 1–38.

Bulkeley, H., & Kern, K. (2006). Local government and the governing of climate change in Germany and the UK. Urban Studies, 43, 2237–2259.

Campbell, J. (1995). Institutional analysis and the role of ideas in political economy. Paper presented to the Seminar on the State and Capitalism since 1800, Harvard University, MA.

Chapman, R. (2003). Policy mix for environmentally sustainable development: Learning from the Dutch experience. New Zealand Journal of Environmental Law, 7(1), 29–51.

Chilvers, J. (2010). Sustainable participation? Mapping out and reflecting on the field of public dialogue on science and technology. Working Paper. Sciencewise Expert Resource Centre, Harwell.

Craft, J., et al. (2017). Catching a second wave: Context and compatibility in advisory system dynamics. The Policy Studies Journal, 45(1), 215–239.

Daland, R. (1981). Exploring Brazilian bureaucracy: Performance and pathology. Washington DC: University Press of America.

Fischer, F. (2003). Reframing public policy: discursive politics and deliberative practices. Cambridge, NY: Oxford University Press.

Gandy, M. (2017). Negative luminescence. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 107(5), 1090–1107.

Givoni, M., & Banister, D. (2012). Speed: The less important element of the high-speed train. Journal of Transport Geography, 22, 306–307.

Grove-White, R., Macnaghten, P., Mayer, S., & Wynne, B. (1997). Uncertain world: Genetically modified organisms, food and public attitudes in Britain. Lancaster, UK: Centre for the Study of Environmental Change, Lancaster University.

Guba, E., & Lincoln, Y. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 105–117). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hajer, M. (2003). Policy without polity? Policy analysis and the institutional void. Policy Sciences, 36(2), 175–195.

Hall, P., & Taylor, R. (1996). Political science and the three new institutionalisms. Political Studies, 44(5), 936–957.

Heazle, M. (2016). The long goodbye Science and policy making in the International Whaling Commission. In Policy legitimacy, science and political authority: Knowledge and action in liberal democracies. pp. 55–80.

Heazle, M., & Kane, J. (2016). Policy legitimacy, science and political authority: Knowledge and action in liberal democracies. Oxford, NY: Routledge.

Howlett, M., & Lejano, R. (2013). Tales from the crypt. Administration & Society, 45(3), 357–381.

Howlett, M., & Mukherjee, I. (2014). Policy design and non-design: Towards a spectrum of policy formulation types. Politics and Governance, 2(2), 57–71.

Howlett, M., & Rio, P. (2015). The parameters of policy portfolios: Verticality and horizontality in design spaces and their consequences for policy mix formulation. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 33(5), 1233–1245.

Howlett, M., Mukherjee, I., & Woo, J. J. (2015). From tools to toolkits in policy design studies: The new design orientation towards policy formulation research. Policy & Politics, 43(2), 291–311.

Howlett, M., McConnell, A., & Perl, A. (2016). Weaving the fabric of public policies: Comparing and integrating contemporary frameworks for the study of policy processes. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, 18(3), 273–289.

Huitema, D., et al. (2009). Adaptive water governance: Assessing the institutional prescriptions of adaptive (co-)management from a governance perspective and defining a research agenda. Ecology and Society, 14(1), 26.

Lasswell, H. (1951). The policy orientation. In D. Lerner & H. Lasswell (Eds.), The policy sciences: recent developments in scope and method (pp. 3–15). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Leonard, D. (2010). ‘Pockets’ of effective agencies in weak governance states: Where are they likely and why does it matter? Public Administration and Development, 30(2), 91–101.

Lin, A. C. (1998). Bridging positivist and interpretive approaches to qualitative methods. Policy Studies Journal, 26(1), 162–180.

Measham, T., Preston, B., Smith, T., Brooke, C., Gorddard, R., Withycombe, G., et al. (2011). Adapting to climate change through local municipal planning: barriers and challenges. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 16(8), 889–909.

Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Perkins, J. R. (2006). De-centering environmental governance: A short history and analysis of democratic processes in the forest sector of Alberta, Canada. Policy Sciences, 39, 183–203.

Rabinow, P., & Sullivan, W. (1979). Interpretive social science: A reader. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Rabinow, P., & Sullivan, W. (1987). Interpretive social science: A second look. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

RCEP. (1998). Setting environmental standards. Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution (RCEP), 22nd Report, London

Roe, E. (1989). Narrative analysis for the policy analyst: A case study of the 1980–1982 medfly controversy in California. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 8(2), 251–273.

Roe, E. (1994). Narrative policy analysis: Theory and practice. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Schulz, C., Martin-Ortega, J., Glenk, J., & Ioris, A. A. R. (2017). The value base of water governance: A multi-disciplinary perspective. Ecological Economics, 131, 241–249.

Skelcher, C., Mathur, N., & Smith, M. (2005). The public governance of collaborative spaces: Discourse, design and democracy. Public Administration, 83(3), 573–596.

Sidney, M. (2007). Policy formulation: Design and tools. In F. Fischer, G. Miller, & M. Sidney (Eds.), Handbook of public policy analysis: Theory, politics and method (pp. 79–87). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Stilgoe, J., Owen, R., & Macnaghten, P. (2013). Developing a framework for responsible innovation. Research Policy, 42(9), 1568–1580.

Stirling, A. (2006). Uncertainty, precaution and sustainability: Towards more reflective governance of technology. In J. Voss & R. Kemp (Eds.), Sustainability and reflexive governance (pp. 225–272). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Stone, D. (1989). Causal stories and the formation of policy agendas. Political Science Quarterly, 104(2), 281–300.

Strauss, J. (1998). Strong institutions in weak polities: State building in republican China: 1927–1940. Cambridge, NY: Oxford University Press.

Swyngedouw, E. (2005). Governance innovation and the citizen: The Janus face of governance-beyond-the-state. Urban Studies, 42(11), 1991–2006.

Wilsdon, J., & Willis, R. (2004). See-through science: Why public engagement needs to move upstream. London: Demos.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Leong, C. Hajer’s institutional void and legitimacy without polity. Policy Sci 50, 573–583 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-017-9301-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-017-9301-5