Abstract

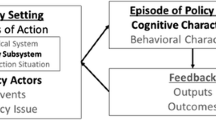

This essay introduces a Policy Conflict Framework to guide and organize theoretical, practical, and empirical research to fill the vacuum that surrounds policy conflicts. The framework centers on a conceptual definition of an episode of policy conflict that distinguishes between cognitive and behavioral characteristics. The cognitive characteristics of a policy conflict episode include divergence in policy positions among two or more actors, perceived threats from opponents’ policy positions, and unwillingness to compromise. These cognitive characteristics manifest in a range of behavioral characteristics (e.g., framing contests, lobbying, building networks). Episodes of policy conflicts are shaped by a policy setting, which consists of different levels of action where conflicts may emerge (political, policy subsystem and policy action situations), interpersonal and intrapersonal policy actor attributes, events, and the policy issue. In turn, the outputs and outcomes of policy conflicts produce feedback effects that shape the policy setting. This essay ends with an agenda for advancing studies of policy conflicts, both methodologically and theoretically.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Policy actors are those individuals actively involved in a policy issue. They may be affiliated or unaffiliated with any type of organization.

We adopt the ACF’s definition of policy subsystems (Jenkins-Smith et al. 2014a) because it is flexible enough to describe similar phenomena including policy regimes (May and Jochim 2013), issue networks (Heclo 1978), policy networks (Adam and Kriesi 2007), and policy space (Krehbiel 1998). It is also useful because the wording “subsystem” denotes the appropriate imagery of being a subset of a political “system.”

We adopt the action situation concept from Ostrom (2005) to connect PCF to decades of research on how institutional arrangements structure actor interactions and the outputs and outcomes of these interactions.

See for example, Heikkila and Weible (2017), who applied the PCF to understand the intensities of policy conflicts in unconventional oil and gas development in Colorado. Even though their work is just one case study, Heikkila and Weible (2017) underscore the importance of the policy setting in shaping policy conflict and the expected diversity of policy conflicts in both description and explanation.

References

Adam, S., & Kriesi, H. (2007). The network approach. In P. A. Sabatier (Ed.), Theories of the policy process (pp. 129–154). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Axelrod, R. M. (2006). The evolution of cooperation (Revised ed.). New York, NY: Basic Books.

Barke, R. P., & Jenkins-Smith, H. (1993). Politics and scientific expertise: Scientists risk perceptions, and nuclear waste policy. Risk Analysis, 13(4), 1585–1595.

Baumgartner, F. R., & Jones, B. D. (1993). Agendas and instability in American politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Baumgartner, F. R., & Leech, B. (1998). Basic Interests: The importance of groups in politics and in political science. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Baumgartner, F. R., Berry, J. M., Hojnacki, M., Kimball, D. C., & Leach, B. L. (2009). Lobbying and policy change. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Bennett, C. J., & Howlett, M. (1992). The lessons of learning: Reconciling theories of policy learning and policy change. Policy Sciences, 25(3), 275–294.

Bentley, A. F. (1908). The process of government, a study of social pressures. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Billig, M. G., & Tajfel, H. (1973). Social categorization and similarity in intergroup behavior. European Journal of Social Psychology, 3(1), 27–52.

Blum, G. (2007). Islands of agreement: Managing enduring armed rivalries. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Clawson, R. A., & Oxley, Z. M. (2017). Public opinion. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press.

Cobb, R. W., & Elder, C. D. (1972). Participation in American politics: The dynamics of agenda-building. Baltimore, MD: The John Hopkins University Press.

Conlan, T. J., Posner, P. L., & Beam, D. R. (2014). Pathways to power. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

d’Estree, T. P., & Colby, B. (2004). Braving the currents: Evaluating environmental conflict resolution in the river basins of the American west. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Dahl, R. A. (1963). Modern political analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc.

Dahl, R. A. (2006). On political equality. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Eck, K. (2012). In data we trust? A comparison of UCDP GED and ACLED conflict events datasets. Cooperation and Conflict, 47(1), 124–141.

Fearon, J. D. (1997). Bargaining, enforcement, and international cooperation. International Organization, 52(2), 269–306.

Forester, J. (2009). Dealing with differences: Dramas of mediating public disputes. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Gais, T. L., & Walker, J. L., Jr. (1991). Pathways to influence in American politics. In J. L. Walker Jr. (Ed.), Mobilizing interest groups in America (pp. 104–111). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Goertz, G. (2006). Social science concepts. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Grossman, M. (2014). Artists of the possible: Governing networks and American policy change since 1945. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Heclo, H. (1974). Modern social policy in Britain and Sweden: From relief to income maintenance. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Heclo, H. (1978). Issue networks and the executive establishment. In A. King (Ed.), The new political system (pp. 87–124). Washington, DC: Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research.

Heikkila, T., & Schlager, E. (2012). Addressing the Issues: The choice of environmental conflict resolution venues in the United States. American Journal of Political Science, 56(4), 774–786.

Heikkila, T., & Weible, C. M. (2017). Unpacking the intensity of policy conflict: A study of Colorado’s oil and gas subsystem. Policy Sciences. (Forthcoming).

Hensel, P. R. (2001). Contentious issues and world politics: The management of territorial claims in the Americas, 1816–1992. International Studies Quarterly, 45(1), 81–109.

Hensel, P. R., Mitchell, S. M., Sowers, T. E., II, & Thyne, C. L. (2008). Bones of contention: Comparing territorial, maritime, and river issues. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 52(1), 117–143.

Howlett, M., & Ramesh, M. (1998). Policy subsystem configurations and policy change: Operationalizing the postpositivist analysis of the politics of the policy process. Policy Studies Journal, 26(3), 466–481.

Huth, P. K., & Allee, T. L. (2002). The democratic peace and territorial conflict in the twentieth century. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Ingold, K., & Varone, F. (2012). Treating policy brokers seriously: evidence from the climate policy. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 22(2), 219–346.

Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology a social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(3), 405–431.

Jenkins-Smith, H. C. (1990). Democratic politics and policy analysis. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Jenkins-Smith, H. C., Nohrstedt, D., Weible, C. M., & Sabatier, P. A. (2014a). The advocacy coalition framework: Foundations, evolution, and ongoing research. In P. A. Sabatier & C. M. Weible (Eds.), Theories of the policy process (3rd ed., pp. 183–224). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Pg.

Jenkins‐Smith, H., Silva, C. L., Gupta, K., & Ripberger, J. T. (2014b). Belief system continuity and change in policy advocacy coalitions: Using cultural theory to specify belief systems, coalitions, and sources of change. Policy Studies Journal, 42(4), 484–508.

Jones, B. D. (2002). Politics and the architecture of choice. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Jones, B. D., & Baumgartner, F. R. (2012). From there to here: Punctuated equilibrium to the general punctuation thesis to a theory of government information processing. Policy Studies Journal, 40(1), 1–20.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, XLVII, 263–291.

Kingdon, J. W. (1984). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Boston, MA: Little Brown.

Knight, J. (1992). Institutions and social conflict. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Knill, C. (2013). The study of morality policy: analytical implications from a public policy perspective. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(3), 309–317.

Krehbiel, K. (1998). Pivotal politics: A theory of US lawmaking. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Kuhn, T. S. (1970). The structure of scientific revolutions (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. L.

Lasswell, H. D. (1971). A preview of policy sciences. New York: Elsevier.

Lewicki, R., Gray, B., & Elliot, M. L. P. (Eds.). (2003). Making sense of intractable environmental conflicts: Concepts and cases. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Lukes, S. (2005). Power: A radical view (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Luskin, R. C. (1990). Explaining political sophistication. Political Behavior, 12(4), 331–361.

Matland, R. E. (1995). Synthesizing the implementation literature: The ambiguity-conflict model of policy implementation. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 5(2), 145–174.

Mattes, M. (2016). “Chipping away at the issues”: Piecemeal dispute resolution and territorial conflict. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 1, 25.

May, P. J., & Jochim, A. E. (2013). Policy regime perspectives: Policies, politics, and governing. Policy Studies Journal, 41(3), 426–452.

McAdam, D., McCarthy, J. D., & Zald, M. N. (Eds.). (1996). Comparative perspectives on social movements. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

McConnell, A. (2010). Understanding policy success: Rethinking public policy. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Meier, K. (1994). The politics of sin. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Mitchell, J. M., & Mitchell, W. C. (1968). Political analysis & public policy: An introduction to political science. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally & Company.

Mucciaroni, G. (2011). Are debates about “morality policy” really about morality? Framing opposition to gay and lesbian rights, Policy Studies Journal, 39(2), 187–216.

Nohrstedt, D. (2010). Do advocacy coalitions matter? Crisis and change in Swedish nuclear energy policy. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 20(2), 309–333.

Nohrstedt, D., & Weible, C. M. (2010). The logic of policy change after crisis: Proximity and subsystem interaction. Risk, Hazards and Crisis in Public Policy, 1(2), 1–32.

Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Pralle, S. B. (2006). Branching out digging In. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Putnam, R. D. (1976). The comparative study of political elites. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc.

Putnam, L., & Wondolleck, J. (2003). Intractability: Definitions, dimensions, and distinctions. In R. Lewicki, B. Gray, & M. L. P. Elliott (Eds.), Making sense of intractable environmental conflicts: Concepts and 34 cases (pp. 35–62). Washington DC: Island Press.

Sabatier, P. A., & Jenkins-Smith, H. C. (1999). The advocacy coalition framework: An assessment. In P. A. Sabatier (Ed.), Theories of the policy process (pp. 117–168). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Schattschneider, E. E. (1960). The semi-sovereign people: A realist’s view of democracy in America. Boston, MA: Wadsworth.

Schneider, A. L., & Ingram, H. (1997). Policy design for democracy. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press.

Snow, C. P. (1959). The two cultures and the scientific revolution. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Stern, P. C., Dietz, T., Abel, T. D., Guagnano, G. A., & Kalof, L. (1999). A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Human ecology review, 6(2), 81–97.

Susskind, L., & Cruikshank, J. L. (1987). Breaking the impasse: Consensual approaches to resolving public disputes. New York: Basic Books.

Tajfel, H., Billig, M. G., Bundy, R. P., & Flament, C. (1971). Social categorization and intergroup behavior. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1(2), 149–178.

Tilly, C., & Tarrow, S. (2007). Contentious politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Weible, C. M. (2008). Expert-based information and policy subsystems: A review and synthesis. Policy Studies Journal, 36(4), 615–635.

Welch, D. D. (2014). A guide to ethics and public policy: Finding our way. New York, NY: Routledge.

Wolf, A. T., Yoffe, S. B., & Giordano, M. (2003). International waters: Identifying basins at risk. Water policy, 5(1), 29–60.

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the AirWaterGas Sustainability Research Network funded by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. CBET-1,240,584. Any opinion, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weible, C.M., Heikkila, T. Policy Conflict Framework. Policy Sci 50, 23–40 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-017-9280-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-017-9280-6