Abstract

Because of Chile’s geographical position, earthquakes and tsunamis are recurrent phenomena and reducing vulnerability to these events is imperative. To do this, one needs to understand the geophysical features of the hazards involved and the vulnerability that exposed communities live with. This article presents some unexpected findings of a research regarding the latter and devised to investigate the vulnerability realities that the devastating 2010 earthquake/tsunami event in Chile exposed. Interestingly, this study revealed households that are formally considered resilient in the face of natural hazards, but are in fact not. These households are part of a group I call the emergent middle. The ‘middle’ because they are neither rich nor poor, but do not fit the typical middle-class category, and ‘emergent’ because their primary concerns are staying out of poverty and climbing the socioeconomic ladder. The findings of this research suggest that they find themselves in a precarious situation and that their vulnerability to natural hazards largely emerges from their economic fragility and their limited access to relevant resources in the wake of a hazardous event. This article is based on data that were collected through extensive field work in the Greater Concepción area and in particular in Talcahuano that was severely hit in 2010.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Because of Chile’s geographical position along the Atacama trench between the Nazca and the South America plates, Chileans are blessed with the beautiful Andes mountain range but are also condemned to face the dangers of recurrent earthquakes and tsunamis. To appraise the extent to which these natural hazards represent a disaster risk, it is important to learn more about both the hazards involved and the vulnerability that exposed communities live with. While numerous studies have examined the geophysical features of earthquakes and tsunamis in Chile (Lomnitz 2004; Kiser and Ishii 2011; Yamazaki and Cheung 2011; Brodsky and Lay 2014; Hayes et al. 2014; Cisternas et al. 2005), only a few have dealt with more societal aspects of vulnerability (Lomnitz 1970; Bitar 2010; Letelier 2010; Mella Polanco 2012; Dussaillant and Guzman 2014). This study aims to contribute to the body of literature dealing with the latter.

On February 27, 2010, the south-central region of Chile was hit by a magnitude-8.8 Mw earthquake that triggered a devastating tsunami (hereafter 27F, in line with Chilean usage). While disasters are devastating events, they also provide a unique window into the complex interaction between two opposing forces: ‘those processes generating vulnerability on the one side, and the natural hazard event (or sometimes a slowly unfolding natural process) on the other’ (Wisner et al. 2004: 46). In other words, 27F could be an opportunity to learn more about vulnerability and in particular the coping capacity and resilience of Chilean households vis-à-vis earthquake and tsunami events. With this in mind, the research described in this article was conceived and fieldwork was undertaken in the Biobio region, one of the most affected areas, 2 years after 27F when the dust had settled and evidence of vulnerable conditions had become more discernible.

In the field, some unexpected observations were made. Specifically, this research found households that are neither poor nor rich, and thus find themselves in the middle, that face significant vulnerability to natural hazards such as earthquakes and tsunami. This was rather surprising since middle-class households are typically considered to be ‘affluent homeowners with access to economic resources, insurance, networks of power and influence in the wider community, and social and cultural capital’ (Fordham and Ketteridge 1999: 27). Only Romero and Vidal (2010) suggest that middle- and lower-middle-class households were disproportionally negatively affected by the 27F tsunami. In this article, I wish to shed light on the plight of these households. The vulnerability of these households seems to represent a blind spot that cannot be ignored in a country that is continuously beleaguered by a wide variety of natural hazards.

The research from which these findings emerged was not aimed at looking into the socioeconomic aspects of vulnerability. However, as the research advanced it became apparent that some socioeconomic observations could not be ignored, mainly because they were unexpected and in some cases even inconsistent with the literature. Against this background, this article aims to share these findings in order to enhance understanding of some vulnerable realities that exist in Chile so that they can be put on both research and policy agendas and as such can hopefully be adequately addressed in the future.

The data were collected from multiple sources using qualitative methods, i.e., from in-depth, semi-structured and group interviews, observations, participation, formal and informal documents, photographs, films. Data were collected in the field, i.e., ‘at the site where participants experience the issue or problem under study’ (Cresswell 2009: 175), in the Greater Concepcion area, particularly in Talcahuano, but also in Concepcion and Hualqui, over a period of 6 months in 2012 and 2013 and 5 months in 2014.

Because the aftermath of a disaster is a sensitive topic, especially to those directly affected, for this research I decided to use snowball sampling, which ‘yields a study sample through referrals made among people who share or know of others who possess some characteristics that are of research interest’ (Biernacki and Waldorf 1981: 141). Using this sampling method, I was able to draw on insiders’ knowledge to locate people who would be willing to recount their stories, which are often hard to tell, for this study. This method enabled me to access a wide variety of people from different socioeconomic backgrounds, ages and even ethnic backgrounds. The respondents in the Greater Concepcion area 47 % were female and 53 % male, aged between 15 and 82. Most respondents were lower, middle or higher middle class (see Fig. 1).

I conducted formal interviews with 62 respondents, 12 group interviews, and engaged in numerous participation/observation opportunities and professionally engaged with various professional institutions dedicated to disaster risk reduction. As I was completely immersed in life in the Greater Concepcion area, almost every interaction in formal and informal events was useful to my study. The software package ATLAS.ti was used to assist the data analysis.

This article is structured as follows. Section 2 briefly describes the theoretical underpinnings of the study, namely how key concepts such as vulnerability, coping capacity and resilience are viewed. Section 3 introduces the ‘emerging middle’ households in Talcahuano and their exposure to earthquake and tsunami hazards. Section 4 then describes the central findings that support the idea that these households from the ‘emerging middle’ find themselves in a precarious situation vis-à-vis earthquake/tsunami disasters. Finally, Sect. 5 presents some conclusions.

2 Vulnerability

2.1 What is vulnerability?

While the ‘hazards’ or ‘agent-specific’ approach remains dominant, it is increasingly agreed that natural hazards only become disasters when they interact with a vulnerable community: ‘there cannot be a disaster if there are hazards but vulnerability is (theoretically) nil, or if there is a vulnerable population but no hazard event’ (Wisner et al. 2004: 43; Warner and Engel 2014; Birkmann 2006). As a result, increasing attention is being given to understanding the vulnerable realities people face vis-à-vis (natural) hazards (Cutter et al. 2008). This is easier said than done, however. Although the word ‘vulnerability’ comes from the Latin verb vulnerare (‘to wound’), the disaster literature provides a wide array of definitions, conceptualizations and approaches. Cardona (2003), for instance, defines vulnerability as ‘the physical, economic, political or social susceptibility or predisposition of a community to damage in the case of a destabilizing phenomenon of natural or anthropogenic origin.’ Cannon et al. (2003: 4–5), on the other hand, emphasizes social vulnerability to highlight that it is about people and their specific characteristics. Vulnerability is not necessarily opposed to coping capacity and resilience but can in fact embrace both. Take, for instance, Watts and Bohle’s (1993) approach to vulnerability, in which they distinguish three basic coordinates:

-

1.

The risk of exposure to crises, stress and shocks (exposure).

-

2.

The risk of inadequate capacities to cope with stress, crises and shocks (capacity).

-

3.

The risk of severe consequences of (potentiality), and the attendant risks of slow or limited recovery (resiliency) from crises, risk and shocks.

Steffen et al. (2004) adopted a similar approach, in which they define vulnerability as a function of ‘(1) exposure—the degree to which a human group or ecosystem comes into contact with particular stresses, (2) sensitivity—the degree to which an exposure unit is affected by exposure to any set of stresses and (3) resilience—the ability of the exposure unit to resist or recover from the damage associated with the convergence of multiple stresses’ (Steffen et al. 2004: 205). There are other approaches, however, that view vulnerability, coping capacity and exposure as separate features. Bollin et al. (2003), for instance, clearly put forward disaster risk as emerging from four independent components, namely hazard, exposure, vulnerability and capacity/measures. I do not subscribe to this latter view as it seems to neglect the complex interactions from which vulnerability emerges. I thus take an approach in line with that of Watts and Bohle.

The key elements of vulnerability, then, are exposure, capacity and resilience. Exposure entails more than spatial exposure and includes social and institutional features, i.e., ‘processes that increase defenselessness and lead to greater danger, such as exclusion from social networks’ (Birkmann 2006: 19; Watts and Bohle 1993, Cannon et al. 2003). Coping capacity is more straightforwardly defined as ‘[t]he means by which people or organizations use available resources and abilities to face adverse consequences that could lead to a disaster’ (UN/ISDR 2004: 16–17). Resilience likewise has many conceptualizations and definitions (Engel and Engel 2012). For Pelling (2003: loc 1229), resilience is a component of vulnerability and ‘the ability of an actor to cope with or adapt to hazard stress.’

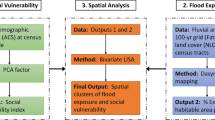

For the purpose of this article, I will use Watts and Bohle’s concept of vulnerability. Since respondents expressed an intrinsic relationship between their experience of vulnerability and their access to and use of specific assets, I will borrow from the livelihood assets of the sustainable livelihood framework (DFID 1999) to structure my findings. This pentagon is central to the livelihood framework and allows the important interrelationships between different assets to become more visible (see Fig. 2). Because asset endowments change, over time the shape of the pentagon that represents a household’s assets also changes.

Asset pentagons presenting different asset portfolios (DFID 1999: 5)

Rather than capital stocks in the strict economic sense of the term, these assets should be viewed as the building blocks of sustainable livelihoods. The following assets are included in the pentagon:

-

1.

Human capital refers to the stock of ‘skills, knowledge, ability to labor and good health that together enable people to pursue different livelihood strategies and achieve their livelihood objectives’ (DFID 1999: 7). Labor is often used to refer to the flow of human capital or ‘the flow of effort, skill and knowledge that humans directly provide as inputs into productive activities’ (Goodwin 2003: 5), although for some authors labor resources are subsumed under human capital. Human capital is important because it is key to making use of the other assets.

-

2.

Social capital refers to ‘the social resources upon which people draw in pursuit of their livelihood objectives’ (DFID 1999: 9). In other words, these resources are the ‘stock of trust, mutual understanding, shared values, and socially held knowledge that facilitates the social coordination of [productive] activity’ (Goodwin 2003: 6) upon which people can draw (networks, social claims, social relations, affiliations, associations). Throughout this article, the distinction between bridging (or inclusive) and bonding (or exclusive) social capital is important. Bonding social capital ‘is inward looking and tend[s] to reinforce exclusive identities and homogeneous groups,’ while bridging social capital is ‘outward looking and encompass[es] people across diverse social cleavages’ (Putnam 2000, chapter 1).

-

3.

Natural capital is the ‘natural resource stock from which resource flows and services (e.g., nutrient cycling, erosion protection) useful for livelihoods are derived’ (DFID 1999: 11). Natural capital is made up of a great variety of resources that include intangible public goods such as the atmosphere and biodiversity to divisible assets used directly for production such as trees or land (DFID 1999: 11). Natural capital is important not just for people who derive their livelihoods from resource-based activities, but for everyone. Human capital, particularly health, for instance, is affected by industrial air pollution.

-

4.

Physical capital includes ‘the basic infrastructure and producer goods needed to support livelihoods’ (DFID 1999: 13). Infrastructure entails changes to the physical environment that enable people to meet basic livelihood needs such as affordable transportation, secure shelter and buildings, access to information. Producer goods include the tools and equipment necessary to function productively.

-

5.

Financial capital refers to the financial resources that people use to achieve their livelihood objectives. As DFID points out, such a definition might not be economically robust since it includes flows as well as stocks and it can contribute to consumption as well as production, although it does capture an important aspect, namely ‘the availability of cash or equivalent, that enables people to adopt different livelihood strategies’ (DFID 1999: 15); in other words, capital that can be invested in order to produce something, at the very least more money for its owner (e.g., cash, credit/debt, savings).

DFID’s definition of social capital includes vertical networks and connectedness (patron/client) that other authors such as Rakodi (1999: 318) term ‘political capital.’ I would, however, like to make a distinction between social and political capital and refer to social capital as horizontal relations (vis-à-vis peers) and to political capital to identify vertical power relations (e.g., vis-à-vis the state or landlord). Political capital then is increasingly related to power and to ‘the extent to which different groups are aware of their rights and willing and able to assert them’ (Carney 2003: 42).

2.2 The social and differential nature of vulnerability

Vulnerability is to a significant extent determined by the social, political and economic environment and is thus essentially social since it emerges from these broader patterns of society. Social, political and economic environments ‘operate to generate disasters by making people vulnerable’ (Wisner et al. 2004: 8). At the same time, vulnerability is differential: Some people are more affected (wounded) by specific hazards than others. So the underlying social (human-made) structures that condition the capacity of specific individuals and groups to respond to, cope with, recover from, ‘adjust to’ or ‘adapt to’ hazards (Cannon 1994: 14; Hewitt 1995: 319; Cutter et al. 2003: 243; Hufschmidt 2011).

Since vulnerability is social and differential, the location of a person or group in the social hierarchy influences not just their life experiences, relationships, opportunities and overall life chances (Fothergill and Peek 2004: 90), but also their vulnerability. Against this background, various vulnerability studies have shown how the poorest stratum of society is generally hardest hit by natural hazards and ‘lose[s] relatively more in disasters… and likewise [has] a more challenging time recovering’ (Phillips et al. 2010: 86; Beatley 1989; Dash et al. 1997; Fothergill and Peek 2004; Wisner et al. 2004; Cannon 1994). The position of the poor in the social hierarchy seriously limits their ability to withstand losses, and this stratum is therefore the most vulnerable in the event of a disaster: ‘[l]ivelihoods that provide people with little more than basic needs are unlikely to enable the provision of self-protection, and any associated lack of social protection for such people will result in high levels of vulnerability’ (Cannon 1994: 24). At the same time, scholars warn that despite the observed high correlation between poverty and vulnerability, ‘vulnerability cannot be read directly off from poverty’ (Wisner et al. 2004: 12).

Most studies, though, seem to be built on a commonly accepted idea that the poor are the most vulnerable to disasters and that higher strata are not, since they have access to sufficient stocks of capital. These higher strata include households from ‘the middle’ since they have transcended poverty and are thus considered self-reliant and resilient. As a result, their levels of vulnerability are rarely investigated. While this assumption seems widespread and forms the basis of many studies of vulnerability, the question is whether it is correct. Does ‘the middle’ in fact have access to sufficient resources, and are they capable of recovering from a disaster in a timely and satisfactory fashion?

3 The ‘emerging middle’: some observations

Throughout this research, I came across households that were neither rich nor poor, but did not fall neatly into the classic middle-class category in terms of education, job security or purchasing power. They seem to have more in common with what the OECD in Latin America has identified as households from the middle sectors: ‘people in the middle—neither the richest nor the poorest in society…[that] are often quite economically vulnerable,Footnote 1 subject to the risk of falling down the economic ladder’ (OECD 2010: 15). According to the OECD study, the narrow focus on poverty alleviation has led to a growing number of ‘emerging’ households that are considered to have overcome poverty and are therefore seen as self-sufficient and self-reliant. Arriagada et al. (2012) also observed this development. They discuss a newly emerged group that cannot necessarily call itself middle class in the traditional sense, but neither is it eligible to benefit from poverty reduction schemes. These households overlap with those that I call households from the ‘emerging middle.’ Their income levels are comparable with those of households in the lower deciles, but the latter receive a significant portion of their income from the government. According to the OECD (2010), this has created ‘many vulnerable households in the lower reaches of the middle sector that are just over the disadvantaged income threshold’ (2010: 16, 71) and are very vulnerable to ‘even short-term shocks, such as temporary lay-off or a period of illness, [since these] can permanently move them back into poverty in the absence of public support’ (OECD 2010: 84). To many middle sector households in Chile, the 27F tsunami was such a shock.

Because of the Chilean government’s narrow focus on poverty alleviation the disadvantaged enjoy public benefits, while households from the ‘emerging middle’—who pay taxes and contribute to the existence of public services—do not. As the OECD (2010: 158) exposes, in addition to the limited eligibility of the majority of middle segment households to receive government assistance, the poor quality of public services compels them to spend significant portions of their income on private education and/or health care for their families, ‘even where the extra cost is a significant additional burden on household budgets’ (OECD 2010: 166). To these households, these costs are important investments. Education, for instance, is often seen as essential to improve social mobility and thus represents an investment in future generations. In addition, over the past 20 years, the level of over-indebtedness of middle-class households has risen substantially as they have taken advantage of the lax rules on the availability of credit. This ‘has led to over-indebtedness in these social groups, from the D to the C2, due to consumer loans for mortgages or children’s education’ (Barozet and Fierro 2011: 31). Indebtedness makes ‘the middle’ even more vulnerable as the substantial costs or ‘investments,’ largely in education and health care, in combination with indebtedness, leads to increasing distress as feelings of financial insecurity rise.

What I also learned about these households from the emerging middle at least the ones from my study is that they seem to share some values. Throughout the interviews it became clear that they find hard work, effort and sacrifice important values, especially in light of their primary objective, which is to improve their socioeconomic situation. For instance, many remarked that, whenever possible, they were willing to pay the extra costs of private healthcare and/or educational opportunities, even if it meant taking out a loan that would take decades to repay. To them these are investments in opportunities for their children and grandchildren, even if stretching their resources in effect also means increasing their overall vulnerability.

It seems that the precarious position of this group in Chile is also closely related to persistently high levels of economic inequality and social differentiation in terms of access to social services such as schools, hospitals and housing, and to opportunities more generally (Larrañaga 2009: 13; Solimano 2011; 2012). Even though Chile has enjoyed significant economic growth and poverty has declined, it faces important challenges that, according to Solimano (2011; 2012), persist as genuine attempts to introduce reforms, improve incomes and wealth distribution, and increase social protection are constrained by ‘the high concentration of economic power and political influence of the dominant elites that block any serious attempt to shift income distribution to the middle income and the working poor.’

In addition, there is some controversy about the accuracy of the actual poverty figures used by the government. In 2008, the economist Felipe Larrain published a study in which he reassessed the official poverty figures by generating a new consumption basket using a household consumption study of 1996–1997. The cost of the new basket was 51 % higher than that of the basket used to define the official poverty line for 2006, which was based on consumption patterns in the 1980s and thus did not reflect recent demographic and economic changes. Based on this reassessment, Larrain arrived at a poverty rate of 29 %, more than double the official rate of 13.7 %. This begs the question of whether some of the households currently considered middle class should in fact be reclassified as poor.

It is important to note that these challenges are accompanied by an overall feeling of discontent that is not helped by a political system that remains ‘a highly elitist affair with low degrees of social participation in public decision-making’ (Solimano 2011: 9). Also, as Cleuren has observed, ‘Chilean politics are marked by low levels of citizen participation, and the recently created participatory initiatives are only instrumental without a genuine commitment of the government to open up the decision-making process to its citizens’ (Cleuren 2007: 14). This has resulted in low levels of trust in government institutions and political parties. According to a survey by the Centro de Estudios Públicos, only 17 % of respondents stated that they have significant trust in the government and a mere 3 % in political parties. The municipalities scored a little better, with 22 %. Such low levels of trust were also reflected in the 2010–2014 World Values Survey, in which 52 % of respondents stated that they have little or no faith in the government and 80 % have little to no faith in political parties (WVS 2014). As Solimano (2011) observed, these challenges make social cohesion in Chile very elusive.

The households discussed here also share similarities with those that Barozet and Fierro (2011) consider middle class. For instance, they also find a segment of the middle sector to which hardly any public policies are directed and who find it difficult to ask and receive assistance because they consider it beneath their dignity: ‘while the poor and more popular segments [of society] can receive and look for state assistance, because of their precarious situations, the Chilean middle sectors either do not qualify for assistance because they have certain resources or simply find it difficult to ask for assistance because they feel it implies lowering themselves’ (2011: 26). The latter idea that receiving assistance is equivalent to lowering oneself I also found throughout my interviews. I learned that to my respondents state assistance had a negative connotation and was often associated with handouts for the needy; as one respondent told me, ‘nobody wants to be “el pobrecito” (the little needy one)’ (interview, 2013). In their eyes, state assistance is not something that citizens might be entitled to in times of unforeseen adverse events, for instance, or an indicator of good governance.

The households that I refer to as the ‘emerging middle’ also appear to overlap with the D and Cb segments in the Esomar Nivel Socio Economico (socioeconomic) marketing scale (Adimark 2000, hereafter NSE Esomar). This letter-based stratification scale classifies households based on two variables, the educational level and occupation of the household’s principal provider, which together determine the NSE of a household. There are five categories:

- A:

-

very high,

- B:

-

high,

- Ca:

-

higher middle,

- Cb:

-

middle,

- D:

-

lower middle.

4 The impact of 27F in Chile, the Biobio region and Talcahuano

Because of Chile’s geographical position, strong earthquakes accompanied by substantial tsunamis are recurrent phenomena (Silbergeit and Prezzi 2012). Consequently, Chile has a significant seismic history, present and future, with ‘a magnitude 7 [earthquake] every 5 years, and a magnitude 4 occurring five times a week’ (Earthquake Engineering Research Institute 2010: 6). One of the regions that is most often struck by strong earthquakes and tsunamis is the Biobio region. This can be explained by its location along ‘the younger portion of the 5000 km subduction zone, where the Nazca plate dives fast with a stronger coupling (tight sticking that causes strong friction between the two plates) with the overriding plate’ (Aon 2010: 4).

The relatively high frequency of earthquakes has moved Chileans to develop a variety of mechanisms to deal with the often adverse effects. For instance, even though internationally it is advised to ‘duck, cover, hold’ when an earthquake strikes, Chileans tend to escape their homes as quickly as they possibly can. This behavior was observed as long ago as 1904, and my interviews suggest that it remains the primary instinctive course of action: ‘[Chilean] inhabitants avoid bodily harm by escaping from their homes because of any moderately perceptible shaking, since there is no telling what might follow; and this praiseworthy custom has been the more successful, as strong shocks are generally preceded by lighter ones’ (Goll 1904). According to a study by Lomnitz, this course of action has been successful at saving lives: ‘the average out-of-doors is safer than the average indoors [and] [r]apid evacuation of dwellings has been effective in preventing or reducing earthquake casualties’ (Lomnitz 1970: 1312). In addition to effective behavior, Chile has also seen great advances in the construction of earthquake-resistant buildings that enable survival even if earthquakes are so strong that standing up and leaving are impossible. This was the case with 27F. The magnitude-8.8 Mw earthquake was so strong that many people were thrown to the floor while trying to escape.

Tsunamis occur significantly less frequently than earthquakes, and as a result there seem to be fewer coping mechanisms. The primary coping mechanism used by coastal communities is based on local knowledge that when a major earthquake strikes (one above magnitude-7.5 Mw) you should run up the nearest hill. While I was unable to find out where and how this local knowledge developed, I did come across the story of origin of the Mapuches (Bengoa 2000), the indigenous people of south-central Chile. Their story begins with a major flood that Mapuches survived because Ten Ten, a snake that lived in the hills, advised them to run up the hill whenever CaiCai, a great snake that lived in the sea, made the sea waters rise. Those who got up the hill survived, while those who did not were transformed into fish. While I did not find a direct connection, it seems that the local knowledge that moved people to run up the nearest hill in response to 27F could have its roots in this story. Since 27F and the large number of deaths caused by the tsunami, Chile is moving toward more tsunami mitigation and preparedness. The municipality of Talcahuano, for instance, is working on evacuation routes and locations (see Fig. 3), increasing tsunami awareness and preparedness, and has built a significant number of supposedly tsunami-resistant dwellings.

The powerful earthquake that struck Chile at 03:34:17 on February 27, 2010, triggered a substantial tsunami that severely impacted 700 km of the south-central coastline (Aon 2010: 10) and caused damage as faraway as California (Information Collection Assessment Team 2010). The main shock was so powerful that it shortened a normal day on earth by 1.26 μs and moved the city of Concepción 3 m to the west and the capital Santiago 28 cm to the west-southwest (Information Collection Assessment Team 2010; Aon 2010). For many coastal localities, the tsunami caused most of the destruction. The overall impacts of 27F were significant—562 lives were lost, 75 % of Chileans were affected, 2 million of them directly, over 200,000 homes were destroyed, and the economic losses have been estimated at US$ 30 billion (EM-DAT 2015; Gobierno de Chile 2010: 5). Furthermore, the main shock was followed by numerous aftershocks, ‘including over 130 magnitude 6 or higher aftershocks within the following week’ (Technical Council on Lifeline Earthquake Engineering 2010, 1). In fact, a magnitude 6.9 aftershock startled guests and journalists just before Sebastian Piñera was to be sworn in as president (Barrionuevo 2010).

Talcahuano, an important port city in the Biobio region, was severely affected by both the earthquake and the tsunami. In total, 37 people lost their lives (21 due to the tsunami), 53,637 people were affected, 1956 dwellings were severely damaged while 6442 suffered minor damage, and 1805 people had to find shelter in camps and 380 in other locations (PNUD 2012: 13).

The tsunami that hit Talcahuano consisted of three waves. The first wave, with a run-up of 5 m (the vertical height of the wave above sea level at its furthest point inland), occurred half an hour after the main seismic shock. The second wave was smaller, with a run-up of 3 m, and reached Talcahuano at 5:15 am. The third wave was the largest, with a run-up of 6 m, and hit Talcahuano at 7:30 am (Quezada et al. 2012; La Tercera 2015: 12). A thick fog covered the city and it was still dark, so few people actually saw the waves. They just heard ‘a nasty sound of dragging iron,’ which later turned out to be the noise of containers and shipping vessels being dragged onshore into the city. Only at daybreak, when the fog dissipated, did people realize what had happened. Aside from destruction, the tsunami deposited a thick layer of oily debris: ‘there was a disgusting blubber…it must have been all the dirt that was on the sea floor…Petrol, fish and other kinds of residue…It was disgusting cleaning it up and it took months to get it all out’ (interviews 2013). As one professional diver remarked, ‘after the tsunami, the ocean was lovely since it had been cleansed’ (interview 2013).

5 Vulnerability in Talcahuano

This research unveiled a group of households from the emerging middle that were not just economically fragile, but in the wake of 27F proved significantly vulnerable to natural hazards. Their vulnerability to natural hazards seems to have primarily emerged from a disproportionate exposure to tsunamis and a limited access to important resources that inhibit their coping capacity and resiliency. Throughout these paragraphs, I will elaborate on these findings. Since my respondents indicated the particular importance of four forms of capital, namely natural, financial, social and political capital, I will borrow these from the sustainable livelihood approach to guide the discussions.

5.1 Exposure

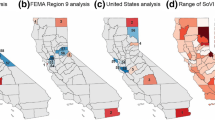

Throughout my research, it quickly became apparent that in Talcahuano some households from the ‘emerging middle’ in particular are experiencing increasing exposure to tsunamis. This was first brought to my attention by one of my respondents, who remarked that Talcahuano had also been affected by a tsunami in 1960 but that it had been largely contained by the area where the Santa Clara neighborhood now stands. This and various other neighborhoods have been built on wetlands that used to absorb and disperse tidal surges and thus damp down the adverse effects of tsunamis. Today, however, these wetlands have been infilled and the area is occupied by families from the middle who were unaware of the tsunami risk they were exposing themselves to by moving to these neighborhoods. In fact, Santa Clara was one of the neighborhoods most affected by the 27F tsunami (UNDP 2011: 27, 2012: 25). That particularly households from the middle are exposed to tsunamis is confirmed when putting together a tsunami risk map and a socioeconomic map of Talcahuano.Footnote 2 Here one sees the predominance of middle- and lower-middle-class households in tsunami-exposed areas (see Fig. 4).

This helps to explain Romero and Vidal’s (2010) finding that middle- and lower-middle-class households were disproportionally negatively affected by the 27F tsunami (see Fig. 5).

Socioeconomic distribution of homes in Talcahuano affected by the 27F tsunami (Source Romero and Vidal 2010)

Investigating this further, it came to light that Talcahuano has been built on two types of territory: a peninsula and an isthmus. The peninsula is high ground and together with the hills on the isthmus is often referred to as ‘the hills.’ To the east of the isthmus, also known as the isthmus of the Low Lands, lies the Rocuant wetland, which is colloquially referred to as ‘the plain’ (see Fig. 6). The isthmus houses approximately two-thirds of the population of Talcahuano and, together with the bays along the shores of the peninsula, is exposed to tsunamis.

Most neighborhoods on ‘the hills’ are unplanned settlements that over time have been normalized by local authorities. Because of their unplanned nature, there are few basic services, such as schools, health care and police presence, and are located at considerable distances from job opportunities, commercial centers and transportation. These neighborhoods are commonly regarded as marginal and unsafe. For instance, when I asked my respondents from the emerging middle whether they would consider moving there they would tell me that was not an option since people there are different and there are fewer opportunities. In terms of their exposure to tsunamis, however, ‘the hills’ are safe.

The majority of ‘the plain’ is wetlands. Historically, these wetlands served to absorb tsunamis and reduce their impact (interviews 2013; Vidal and Romero 2010: 1; Bucci 2013) and were not allowed to be urbanized. Throughout the second half of the twentieth century, however, the city experienced significant growth (since 1970 the urban area of Talcahuano has doubled). The demographic pressure, in combination with the liberalization of the land market, eventually led to the urbanization of areas exposed to natural threats, like tsunamis and flooding (Vidal and Romero 2010: 11). The development of the wetlands was attractive to real-estate companies since building on (steep) hills is technically more complex and thus more expensive (Pauchard et al. 2005: 274). So when the land market was liberalized and permission was granted to develop previously restricted areas, real-estate companies jumped at the opportunity to buy and develop the wetlands cheaply and sell homes at profitable margins (interviews Talcahuano 2013–2014), even though this meant doing away with Talcahuano’s mitigation area and placing more people at risk: ‘In 1960 we had a tsunami here in Talcahuano, but it was largely absorbed by the area where I now live’ (interviews Talcahuano 2013). Real-estate companies endorsed the commonly accepted idea that wetlands were wasteland that could provide a greater public service if drained and filled in (Pauchard et al. 2005: 274). Since then large parts of Talcahuano’s wetlands have been used to develop residential areas, and they continue to be urbanized.

These new residential areas were perfect for young families aspiring to a better way of life with access to basic services, commercial centers and transportation. As a result, by 2010, these neighborhoods were occupied by a large number of households I have labeled ‘the middle.’ These households had no idea that this upward movement would come at the expense of increasing their exposure to natural hazards. They assumed that the (local) authorities would never allow the development of unsafe land and the subsequent sale of ‘unsafe’ houses, just as they do not permit the sale of unsafe goods in supermarkets. To what extent this assumption was false became apparent in the wake of 27F.

Even though the respondents residing on the wetlands expressed they were unaware of their exposure, coastal communities know that in case of a real earthquake, i.e., of more than 7.5 Mw, they should climb the nearest hill. This latent knowledge that is part of a greater disaster subculture (Engel et al. 2014) saved many people so that the number of deaths in Talcahuano due to the tsunami was limited. Still some people died, mainly either because they did not believe a tsunami would affect them or because the authorities assured them there was no threat and they should return to their tsunami-exposed homes.

While some households have resettled since 27F, most residents do not want to leave. The households that were part of this study revealed they felt strong ties to their neighborhoods. They revealed that these feelings were primarily related to the time and energy they had invested in developing a perfect living situation for their families. From what I have seen, in the Greater Concepción area it is common to buy a home at an early stage of family life which can be expanded in time and in such a way as to provide the family with the right living conditions, including the social and built environment. Over time, these investments result in unique homes that are tailor-made and satisfy all the family’s specific needs. Against this background, leaving becomes undesirable. Leaving implies leaving behind the product of years of effort, sacrifice and financial investment. Moreover, interviews revealed that often these families do not have the resources to start all over. For instance, households from this study expressed that moving to ‘the hills’ is not an option, largely because of the prevalence of poverty and high crime rates and the distance to resources and services. Leaving would thus entail a decreased sense of security on a daily basis, and putting at risk the access to relevant resources they do have. Leaving would, for example, mean losing a social environment that for many is key to their household’s resilience. In other words, the households that are discussed here continue to live in neighborhoods that are substantially exposed to tsunamis.

5.2 Natural capital

The rapid urbanization and industrialization of Talcahuano has had a negative impact on the environment. For instance, for decades waste was dumped indiscriminately, particularly into the sea. However, as a Balinese once told me, the sea always returns whatever is dumped in its waters. This seems to have been the case in Talcahuano, as the retreating tsunami left a thick black micro layer of oily waste containing high concentrations of bacteria, viruses, toxic metals and organic pollutants on shore. The wetland areas affected by the tsunami were also covered by this layer, and the pollutants it contained were to some extent absorbed into the soil. Few studies have been done to determine the extent of the contamination so that residents are unaware of the potential risks they face residing on this contaminated land (interviews 2013, Fariña et al. 2012).

In addition to the contamination, the residents of the wetland neighborhoods are exposed to several other risks. Infilled wetlands tend to amplify earthquake waves due to their ‘soft’ soils and sediments. Such amplification can result in greater damage. In addition, wetlands tend to suffer from liquefaction, which ‘involves the temporary loss of strength of sands and silts which behave as viscous fluids rather than soils … when seismic waves pass through a saturated granular layer of uncohesive sediments, distorting the granular structure and causing some of the void spaces to collapse’ (Alexander 1999: chapter 4) and ‘[w]idespread liquefaction-induced ground deformation and related damage to soils and foundations occur to spectacular and devastating effect in almost every strong earthquake’ (Huang and Yu 2013). Liquefaction can thus have significant consequences, such as ‘the collapse of foundations or the settling of structures’ (Alexander 1999: chapter 4). During the 27F earthquake, ‘several coastal and river vicinities experienced extensive liquefaction…’ (Technical Council on Lifeline Earthquake Engineering 2010: 6). Because liquefaction can cause catastrophic failures in building structures (Verdugo 2012: 708), Alexander (1999: chapter 4) has argued that it is best to avoid building on such susceptible terrains.

The wetland neighborhoods of Talcahuano have already experienced liquefaction and will continue to do so in the future. Because of the lack of comprehensive studies of the state of the soil beneath the wetland neighborhoods, it remains unclear to what extent the soil has been negatively affected by the 27F earthquake and tsunami. The consequences include increasing exposure to the dangers associated with liquefaction in the event of future earthquakes. Much remains unknown, but it is clear that residing on infilled wetlands in a region that is repeatedly subjected to strong earthquakes and tsunamis entails exposure to a variety of substantial dangers.

Infilling wetlands for the development of residential areas for the ‘emerging middle’ households has not just enhanced their exposure, but has also reduced the stock of natural capital available to provide protective services and subsequently decrease the probability of a disaster occurring or reducing the damage in case of an event, that is, the wetlands enabling flood control and mangroves attenuating wave and storm surges (Kousky 2010). Combine this with the contamination and liquefaction of the soil on which most of these households reside since 27F, and we can conclude that their natural capital, and that of the community at large, has been severely reduced.

5.3 Financial capital

The households from this study expressed that their limited access to financial resources seriously limits their ability to recover in an adequate and timely fashion. Having access to financial capital can, for example, enable a family to absorb the loss of their belongings or to arrange satisfactory temporary housing. For the respondents of this study, the reality was, however, that already before 27F their stock of financial capital was minimal as their situation together with others from the middle sectors was economically fragile. So in the wake of 27F, this fragility was exposed and they found themselves with no financial resources to absorb the adverse impacts and recover. The respondents of this study exposed that neither the state or any other formal organization acknowledged their financially fragile situation and subsequent limited access to financial capital for recovery. Subsequently, even in the wake of 27F they were still not eligible to receive state assistance.

Despite Chile’s extensive experience with major earthquake/tsunami event, the government did not have specific tools to be used in the wake of an earthquake/tsunami disaster. They therefore used existing mechanisms that worked in ‘normal’ situations, such as the Ficha de Proteccion Social (Social Protection Card, Chile Atiende 2015), to determine, for instance, a family’s level of vulnerability in light of 27F.Footnote 3 This instrument was not adapted to ensure that post-disaster needs were satisfied, however, and led to some households from ‘the middle’ with higher post-27F scores, i.e., more affluent, than before 27F (interviews Talcahuano 2013 and 2014; Chamorro et al. 2011). This seems unfair, to say the least, but it did determine the level and kind of assistance these households were, or were not, eligible to receive.

The ‘emerging middle’ households in Talcahuano experienced various kinds of damage. Some families with one-story dwellings and exposed to tsunamis lost practically everything, while others with two-story dwellings mainly lost belongings from their living room, dining room and kitchen, such as sofas, chairs, tables and electrical appliances (fridges, washing machines, dryers, televisions, kitchen appliances, sound equipment, etc.). While some things could be recovered with dedication and patience, most of the losses would have to be recovered over time whenever the households’ income would allow it. Since the ‘emerging middle’ households from this study had little or no financial buffers, they had to hold on to their jobs or find work as quickly as possible. This is what most of them, and in particular the men of these households, did. However, many companies in Talcahuano, like fisheries, had also been affected, so that job opportunities were scarce. Moreover, respondents revealed that some companies applied article 159 No. 6 of the Chilean Labor Code enabling them to fire workers due to a ‘fortuitous event or force majeure’ without compensation. One respondent reported that ‘They fired my husband who worked in San Vicente…interestingly enough, the company was hardly affected by the earthquake and even less by the tsunami…[but] after 2 months they took them [him and other employees] all back. As he was fired and left without any money…he was forced to leave Talcahuano and find work in the south’ (interview Talcahuano 2014). Even though some menFootnote 4 got their jobs back after a while, many households were left without an income at a time when they needed it most. Men who could not find a job in or near Talcahuano left their families behind to look for work elsewhere, which meant that many women were left in charge of most of the recovery process at home.

Because poorer households were eligible for financial assistance, there are cases where one could state that households from the ‘emerging middle’ are now worse off than those from poorer segments. I encountered several cases where this could be said. For instance, take one of my respondents from a lower segment of society. She is a Colombian single mother who came to Chile with nothing. When 27F hit, she was living with a friend in Santa Clara. She did not have a house, possessions, a job, anything. In the wake of 27F, she was able to acquire a house, goods and more importantly technical schooling to become a beautician. In other words, 27F made it possible for her to acquire a home and new skills that enabled her to earn a permanent income to ensure a livelihood. When comparing this story with those from the emergent middle households, some of whom still do not have a home 4 years after the tsunami and are still working hard to even come close to where they were before, one starts to wonder how assistance should be framed and distributed. From my study, it seems that these households are largely on their own and this could be significantly delaying their recovery. More research is necessary, however.

According to my respondents, the limited public policies directed at the emergent middle households, also in the wake of a disaster, significantly inhibited their access to financial capital and subsequently their ability to recover in a timely fashion. Their recovery often entailed finding employment to ensure an income, and over time, little by little, finding ways to set aside resources to replace what they had lost. For most, any kind of recovery required first and foremost an income to spend on daily necessities and from which to start accumulating financial resources to construct a new home (interviews 2013–2014).

Finally, the few mechanisms that were available to affected ‘middle’ households were often not responsive to their actual needs. One of my respondents explained for instance how she had only two real options to recover her house. The first option involved government assistance, but this forced the family to move from their relatively decent hill neighborhoodFootnote 5 to a tsunami-affected and exposed area, and to leave behind the important social capital the family had built up over decades in their old neighborhood. In other words, receiving government assistance required giving up substantial levels of natural and social capital. The other option was to work until they could build a solid house on their land. This, however, would take a long time and forced them to continue living in the emergency accommodation until they succeeded. Since the family still owns the land on which their house is located, the ideal solution would be for the government to enable financial assistance to reconstruct a new, more solid house that can resist future earthquakes.

5.4 Political capital

For the households that I talked to, values like personal effort, sacrifice and self-sufficiency are very important. However, upholding these values seems to inhibit their access to political capital. Such values for instance discourage these households from making their grievances known and mobilizing powerful actors to address them.

These households value effort and pride themselves on achieving the life they have through hard work and sacrifice. This is why they would not become emotional at the loss of their physical house, but rather at the loss of their home; the loss of the results of years of labor, overcoming obstacles, and the sacrifices and effort involved. It is the realization that this can be lost from one moment to the next: ‘my mother put in all the effort and sacrifice to have her house…that’s what hurts. But then I tell my mother, “that is not what matters”. We are alive. We can continue to sacrifice to have a house again. It will not be immediate because it is difficult, but at some moment we will have a house again’ (interview Talcahuano 2013). What this quotation highlights is the hurt, but also the firm belief in one’s capability to attain what one desires. From my sample, households from ‘the middle’ believe that if they put in the effort again, they will over time replace all they have lost. It might take time, blood, sweat and tears, but that’s life. This ‘effort’ ethos enables them to do what has to be done, with few complaints, but the substantial levels of acceptance also prevent them obtaining support from outside.

In addition to valuing effort, self-sufficiency is very important. My respondents from the ‘emerging middle’ would not easily ask for any kind of assistance. In particular, government assistance is perceived as ‘charity’ for ‘the needy.’ Since these households do not wish to be viewed as ‘needy’ and generally are not viewed as needy and thus do not receive much assistance, they are not keen and rather hesitant to request government assistance. While it is admirable how these households get up and start rebuilding their lives on their own, this attitude isolates them, makes them rather invisible and inhibits a speedy recovery, perhaps by mobilizing political capital. From my study, it seems that political capital is very important in Chile and can enable access to a great variety of resources. One does have to play the game, however, which entails first and foremost mobilizing the media to visibly display one’s grievances. The households I talked to have worked hard to avoid a ‘needy’ livelihood and status, so this game seems unacceptable. They would prefer a lengthy but dignified recovery process to a short and unbecoming one. Households from the ‘emerging middle’ have worked hard to not be needy, and portraying their family’s grievances for everyone to see in order to receive what they perceive as charity does not match their normative and valuative schemes. They see themselves as upwardly mobile and so do not wish to be identified with the extremely vulnerable ones that receive assistance after investing everything they have in order not to be needy.

In fact, even though the constitution (Constitución Politica de la Republica de Chile 1980) provides them with a right to safety and security, for instance, ‘the middle’ view such rights in a negative light, as something that is a luxury, an extra. In addition, demanding one’s rights is often considered as being rowdy and disruptive and thus does not fit their image of themselves as decent, participating citizens. Such imagery is, however, befitting the Mapuches as they struggle to see their human rights respected, for instance (interviews 2013–2014). From my time in the Greater Concepción region I learned that demanding ones rights to be respected is considered somewhat unruly and the households I engaged with preferred to stay out of trouble, accept what is and expect nothing more. In addition, as their low levels of trust in the political system also demonstrate, they do not believe that political engagement can make a difference for them. So why bother, if one is additionally too busy working to stay afloat.

Because these households largely fend for themselves and do not seek outside assistance they are rather easily ignored and generally very invisible, unlike those living in emergency camps occupying a public space, for instance. Poorer segments of society, moreover, seem increasingly to be part of the political system. Since government policies are generally pro-poor, they are part of the institutional landscape. They have direct contacts with government official and are familiar with bureaucratic processes. In addition, they are not bothered when it comes to making their grievances known through the media and seem quite capable when it comes to accessing relevant resources. This makes them visible and provides them access. In this sense, it appears that their political capital is more substantial than that of ‘the middle.’

The lack of visibility of the households that I talked to from the ‘emerging middle’ has significantly affected their access to both formal and informal relief. Since the provision of relief was not well informed, guided or coordinated, the quality and quantity of the assistance was often insufficient, but the households from ‘the middle’ would be the last to receive whatever there was because assistance would first go to wherever TV and radio journalists were reporting from. For many the media was the primary source of information. TV and radio reports largely informed the choice of location and type of assistance. This led to some areas, particularly those where people were open about their grievances, overflowing with relief and others, mostly ‘the middle’ neighborhoods, receiving very little. The neighborhood of Villamar, for instance, had been inundated by the tsunami but received no media attention, since the media was focusing on the fishing community of Tumbes and the coastal neighborhood of Santa Clara.

5.5 Social capital: ‘in life, good friends are more valuable than money’ Footnote 6

According to respondents from this study, the lack of access to different forms of capital forced them as households from ‘the middle’ to heavily rely on their informal social networks, more specifically on what Putnam (2000) labeled bonding social capital. Bonding social capital refers to forms of social capital that are inclusive, inward looking and ‘tend to reinforce exclusive identities and homogeneous groups’ (Putnam 2000: chapter 1). Bridging social capital, on the other hand, includes forms of social capital that are more ‘outward looking and encompass people across diverse social cleavages’ (Putnam 2000: chapter 1). It seems that households from ‘the middle’ have limited trust in people outside their direct social networks. As a result, they relied mostly on bonding social capital and turned to their extended family and informal networks to meet their needs and provide emergency accommodation, food and other resources they needed to cope with the effects of 27F. ‘Networks of reciprocity…play[ed] an important role…in creating an informal social security system to survive’ (Lomnitz 1988: 42), as’[t]he relief; the support, came from family and friends more than from some kind of institution’ (interviews Talcahuano 2013). Because of this, neighborhoods largely populated by ‘the middle’ households did not need to stay in emergency camps or homes (mediagua); ‘many stayed with friends or family, at least for a while, until after a while such housing situations become more difficult and they are not welcome anymore’ (interviews Talcahuano 2013). Today, after 5 years, some are still living their family or friends because they have not yet been able to accumulate sufficient resources to pay for adequate accommodation. While it is great that this type of assistance gave many people a roof over their head, an emergency situation of 4 years in which two families are forced to share one small home is far from ideal.

As Lomnitz and Sheinbaum (2004) indicate, it is not surprising that in times of substantial need people turn to their extended family: Significant favors, like rebuilding a home, require a matching level of trust or ‘confianza.’ To this end, the fact that extended families in Chile include not only biological family members but also close friends and tend to be extended terms of both numbers and geographical distance is favorable. This became evident as family members and friends from far beyond the affected region organized themselves to provide assistance for those in need. In fact, these networks are global, but are mobilized to first and foremost assist members of the family. Subsequently, when 27F happened, extensive networks were activated and assistance came to Talcahuano from all over the world.

Already in 1971 did Lomnitz observe the importance of informal social networks that are largely held together by trust, for the Chilean ‘middle’ (Lomnitz and Sheinbaum 2004: 4). She found that these networks were crucial for the Chilean middle to get access to required resources (Barozet 2006: 23). In fact, she stressed that they were particularly valued by those who cannot seem to escape some form of social vulnerability since they enable them access to protection and security through social rather than economic capital. From this study, it became evident that this remains so. In fact, the findings corroborate that these institutions are not residues of some ‘pre-modern’ society but are important forms of capital in societies ‘where the state and market have failed to adequately insure the satisfaction of needs of all members of society’ (Lomnitz and Sheinbaum 2004: 7). My findings support this idea for ‘the middle’: ‘the support of a social group for which [they felt] sufficient trust [and they could] rely on […] for major emergencies as well as for the satisfaction of [their] most immediate needs’ (Lomnitz and Sheinbaum 2004: 7) was key to ‘the middle.’ Most if not all of the recovery process, whether it involved providing emergency accommodation or cleaning up debris, rested on existing informal social networks of exchange.

The need to rely on these informal social networks was exacerbated by the often unsound and unreliable functioning of the government. For instance, the failure of the tsunami warning system (Wisner et al. 2012: chapter 26) due to prevalent inadequacies and incompetence throughout the government system led to a substantial number of unnecessary deaths and to diminished faith in the competence of state institutions. This faith was further diminished by the major delays and unreliability of government assistance due to numerous instances of fraud and bad practices. This compelled households to respond with the capital they had, i.e., social capital, to satisfy their needs.

6 Conclusion

If we go back to our approach of vulnerability, we have to conclude that a subsection of the middle-level households in Talcahuano, which we called the ‘emerging middle,’ seem more vulnerable than is generally assumed, or described in the literature. Just like anyone else in Chile they are exposed to earthquakes, but unlike most other socioeconomic segments they are also disproportionately exposed to tsunamis. And while their capacity to rebound seems high, their resilience seems to be low, and deteriorating. Their exposure is largely the result of the location of newly developed residential areas in highly exposed areas. Besides, these households have limited financial capital, i.e., opportunities to finance the cleanup and reconstruction necessary to rebound, that in light of the devastation caused by 27F has only further decreased. Finally, they command relatively low levels of political capital, which continues to be low. Fortunately for them, social capital was available to enable them to overcome the first blows, but one has to wonder to what extent they would be able to mobilize this social capital if another major adverse event were to occur. If we take this information and present it through the asset pentagons presented in Fig. 5. Here you clearly see how their asset portfolio was already frail, but since then has deteriorated to unhealthy proportions (Fig. 7).

This study adds to research presented by the OECD, scholars like Solimano (2011, 2012), Barozet and Fierro (2011), and Arriagada et al. (2012), identifying a vulnerable middle segment that seems to receive little or no consideration in the wake of disasters such as 27F. This ‘emerging middle’ is a rather new group that does not fit traditional middle-class frameworks. Although capturing the realities faced by this group remains difficult, this should not prevent researchers and policymakers approaching their concerns and finding ways to respond to their grievances. In ‘peacetime,’ when lives have not been disrupted by the effects of an adverse event, this group may be successful when it comes to overcoming poverty and ensuring upward mobility. But the investments necessary to do so leave these households with an extremely limited asset portfolio that does not provide the necessary buffer they need to ensure their resilience. As a result, upwardly mobile households are extremely vulnerable to unforeseen crises, stresses and shocks. In a country like Chile, where hazardous events are frequent, substantial levels of resilience are necessary. Since January 2014, for example, Chilean households have had to respond to a magnitude-8.2 earthquake/tsunami event near Iquique, devastating floods in the Atacama Desert, a disastrous fire in Chile’s primary port city Valparaiso that left thousands homeless, and three eruptions of the Chalbuco volcano.

Disasters like 27F should therefore be taken to learn more about realities faced by specific groups of vulnerable households, and the lessons learned should provide a starting point for change to increase their resilience. As the findings of this research show, increasing the resilience and reducing the vulnerability of these households does not require handouts, but rather enabling them to build up an adequate asset portfolio that will allow them to (1) reduce their exposure to risks, (2) improve their capacities to cope with unforeseen events and (3) absorb the adverse effects of events and ensure their adequate and timely recovery.

Notes

I will refer to economic fragility instead of economic vulnerability to prevent confusion regarding vulnerability.

The Social Protection Card (Ficha de Proteccion Social) is an instrument that is used to determine whether persons or households are entitled to state benefits. To access such benefits, the person/household should be either (socioeconomically) vulnerable or poor. To determine the socioeconomic status of the person/household at hand, a survey is used. This survey registers various aspects, such as age, education, health and income, which are later used to calculate a score and determine the person's/household's (socioeconomic) status (Chile Atiende 2015).

My data suggests that in Talcahuano, men are the principal breadwinners.

There is a handful of hill neighborhoods, mostly the older ones, that are decent to live in. In fact, some of these used to host the older and more affluent families of Talcahuano.

“En la vida màs vale tener amigos que dinero” is a common saying in Chile.

References

Adimark (2000) El Nivel Socio Economico Esomar: Manual de Aplicacion. www.microweb.cl/idm/documentos/ESOMAR.pdf. Accessed 29 July 2015

Alexander D (1999) Natural disasters, Kindle edition edn. Kluwer, Dordrecht

Aon (2010) Event recap report: 02/27/10 Chile earthquake. www.aon.com/attachments/reinsurance/201003_ab_if_event_recap_chile_earthquake_impact_forecasting.pdf. Accessed 4 Feb 2015

Arriagada I, Campo del E, Daude C, Grynspan R, Lopez-Calva LF, Lustig N, Malagon J, Moran ML, Ocampo JA, Oliveira L, Ortiz-Juares E, Paramio L, Sojo A, Vega M, Visacovsky S (2012) Clases Medias en Sociedades Desiguales. Pensamiento Iberoamericano

Barozet E (2006) El Valor Histórico del Pituto: Clase Media, Integración y Diferenciación Social en Chile. Revista de Sociologia del Departamento de Sociología de la Universidad de Chile 20:69–96

Barozet E, Fierro J (2011) Clase Media en Chile, 1990–2011: Algunas Implicancias Sociales y Políticas. Santiago de Chile: Fundación Konrad Adenauer. www.kas.de/wf/doc/kas_29603-1522-4-30.pdf?111202200649. Accessed 4 Feb 2015

Barrionuevo A (2010) Aftershocks jolt Chile as new president is sworn in, New York Times, March 11, 2010. www.nytimes.com/2010/03/12/world/americas/12chile.html. Accessed 4 Feb 2015

Beatley T (1989) Towards a moral philosophy of natural disaster mitigation. Int J Mass Emerg Disasters 7(1):5–32

Bengoa J (2000) Historia del Pueblo Mapuche. LOM Ediciones, Santiago de Chile

Biernacki P, Waldorf D (1981) Snowball sampling: problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociol Meth Res 10(2):141–163

Birkmann J (ed) (2006) Measuring vulnerability to promote disaster-resilient societies: conceptual frameworks and definitions. In: Measuring vulnerability to natural hazards: towards disaster resilient societies, ch. 1. UN Universities Press, Geneva. http://archive.unu.edu/unupress/sample-chapters/1135-MeasuringVulnerabilityToNaturalHazards.pdf

Bitar S (2010) Doce Lecciones del Terremoto Chileno. Revista Chilena de Administración Publica 15(16):7–18. doi:10.5354/0717-8980.2010.11205

Bollin C, Cárdenas C, Hahn H, Vatsa KS (2003) Disaster risk management by communities and local governments. Interamerican Development Bank. http://publications.iadb.org/handle/11319/4642?locale-attribute=en. Accessed on 31 July 2015

Brodsky E, Lay T (2014) Recognizing foreshocks from the 1 April 2014 Chile earthquake. Science 16:700–702. doi:10.1126/science.1255202

Bucci F (2013) La complicidad de la planificaciónurbana en la creación de territorios en riesgo: el caso de las inundacionesurbanas en la ciudad-puerto de Talcahuano. Seminario para optar al Título Profesional de Administrador Público con Menciónen Gestión Pública. Universidad de Concepción, Concepción

Cannon T (1994) Vulnerability analysis and the explanation of ‘natural’ disasters. In: Varley A (ed) Disasters, development and environment. Wiley, Chichester, pp 13–30

Cannon T, Twigg J, Rowell J (2003) Social vulnerability. Sustainable Livelihoods and Disasters, Report to DFID Conflict and Humanitarian Assistance Department (CHAD) and Sustainable Livelihoods Support Office. file:///C:/Users/Karen%20Engel/Downloads/6377.pdf. Accessed 29 July 2015

Cardona OD (2003) The need for rethinking the concepts of vulnerability and risk from a holistic perspective: a necessary review and criticism for effective risk management. In: Bankoff G, Frerks G, Hilhorst D (eds) Mapping vulnerability: disasters, development and people, ch. 3. Earthscan, London

Carney D (2003) Sustainable livelihoods approaches: progress and possibilities for change. www.eldis.org/vfile/upload/1/document/0812/SLA_Progress.pdf. Accessed 4 Feb 2015

Centro de Estudios Públicos (2015) Estudio Nacional de Opinión Pública N° 73. http://www.cepchile.cl/dms/archivo_5916_3714/EncuestaCEP_Abril2015.pdf. Accessed 31 July 2015

Chamorro S, Herrera H, Mathivet C, Pulgar C, Valdivieso E, Vergara P (2011) Informe para la Relatora Especial de Naciones Unidas para el Derecho a la Vivienda Adecuada de las Organizaciones de Apoyo del Movimiento Nacional por la Reconstrucción Justa. file:///C:/Users/Mafi/Downloads/Informe_Relatora%20ONU_sept2011.pdf. Accessed 9 Feb 2015

Chile Atiende (2015) Ficha de Protección Social. www.chileatiende.cl/fichas/ver/35332. Accessed 29 July 2015

Cisternas M, Atwater B, Torrejón F, Sawai Y, Machuca G, Lagos M, Eipert A, Youlton C, Salgado I, Kamataki T, Shishikura M, Rajendran CP, Malik J, Rizal Y, Husni M (2005) Predecessors of the giant 1960 Chile earthquake. Nature 437:404–407

Cleuren H (2007) Local democracy and participation in post-authoritarian Chile. Eur Rev Lat Am Caribb Stud 83:3–18

Constitución Politica de la Republica de Chile de 1980 (2003) www.camara.cl/camara/media/docs/constitucion_politica.pdf. Accessed 4 Feb 2015

Cresswell J (2009) Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Cutter S, Boruff B, Shirley L (2003) Social vulnerability to environmental hazards. Soc Sci Q 84(2):242–261

Cutter SL, Barnes L, Berry M, Burton C, Evans E, Tate E, Webb J (2008) A placed-based model for understanding community resilience to natural disasters. Glob Environ Changes 18:598–606

Dash N, Peacock W, Morrow B (1997) And the poor get poorer. In: Peacock W, Morrow B, Galdwin H (eds) Hurricane Andrew: ethnicity, gender, and the sociology of disasters. Routledge, New York, pp 206–225

DFID (1999) Sustainable livelihood guidance sheet. Department for International Development, London. www.eldis.org/vfile/upload/1/document/0901/section2.pdf. Accessed 29 July 2015

Dussaillant F, Guzman E (2014) Trust via disasters: the case of Chile’s 2010 earthquake. Disasters 38(4):808–832. doi:10.1111/disa.12077

Earthquake Engineering Research Institute (2010) The 27 February 2010 Central South Chile earthquake: emerging research needs and opportunities. www.eqclearinghouse.org/co/20100227-chile/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/Chile-Workshop-Report_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 4 Feb 2015

EM-DAT (2015) The international disaster database. http://emdat.be/country_profile/index.html. Accessed on 5 Feb 2015

Engel K, Engel P (2012) Building resilient communities: where disaster management and facilitating innovation meet. In: Wals A, Blaze Corcoran P (eds) Learning for sustainability in times of accelerating change. Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen

Engel K, Frerks G, Velotti L, Warner J, Weijs B (2014) Flood disaster subcultures in the Netherlands: the parishes of Borgharen and Itteren. Nat Hazards 73:859–882

Fariña LM, Opaso C, Puz PV (2012) Impactos Ambientales del Terremoto y Tsunami en Chile. Las Replicas Ocultas del 27F. Fundación Terram, Santiago de Chile

Fordham M, Ketteridge AM (1999) “Men Must Work and Women Must Weep”: Examining gender stereotypes in disasters. In: Enarson E, Hearn Morrow B (eds) The gendered terrain of disaster: through women’s eyes. IHC, Miami

Fothergill A, Peek L (2004) Poverty and disasters in the United States: a review of recent sociological findings. Nat Hazards 32(1):89–110

Gobierno de Chile (2010) Plan de Reconstrucción Terremoto y Maremoto del 27 de Febrero de 2010. www.preventionweb.net/files/28726_plandereconstruccinagosto2010.pdf. Accessed 5 Feb 2015

Goll F (1904) Die Erdbeben Chiles. Theodor Ackermann, München. https://ia902609.us.archive.org/17/items/dieerdbebenchil00dessgoog/dieerdbebenchil00dessgoog.pdf. Accessed 26 Oct 2015

Goodwin NR (2003) Five kinds of capital: useful concepts for sustainable development. G-DEA Working Paper No. 03-07. http://www.ase.tufts.edu/gdae/publications/working_papers/03-07sustainabledevelopment.pdf. Accessed on 31 July 2015

Hayes G, Herman M, Barnhart W, Furlong K, Riquelme S, Benz H, Bergman E, Barrientos S, Earle P, Samsonov S (2014) Continuing megathrust earthquake potential in Chile after the 2014 Iquique earthquake. Nature 512:295–298. doi:10.1038/nature13677

Hewitt K (1995) Excluded perspectives in the social construction of disaster. Int J Mass Emerg Disasters 13(3):317–339

Huang Y, Yu M (2013) Review of soil liquefaction characteristics during major earthquakes of the twenty-first century. Nat Hazards 65:2375–2384

Hufschmidt G (2011) A comparative analysis of several vulnerability concepts. Nat Hazards 58:621–643

Information Collection Assessment Team (2010) After action report Chile earthquake. http://emergency.lacity.org/stellent/groups/departments/@emd_contributor/documents/contributor_web_content/lacityp_015617.pdf. Accessed 4 Feb 2015

Kiser E, Ishii M (2011) The 2010 Mw 8.8 Chile earthquake: triggering on multiple segments and frequency-dependent rupture. Behav Geophys Res Lett 38(7):1–6. doi:10.1029/2011GL047140

Kousky C (2010) Using natural capital to reduce disaster risk. J Nat Res Policy Res 2(4):343–356

La Tercera (2015) Olas de 5 Metros Azotan Talcahuano y Arrastran Embarcaciones y Casas. February 28, 2010, p 12. http://diario.latercera.com/2010/02/28/01/contenido/9_25219_9.html. Accessed 4 Feb 2015

Larrain F (2008) Cuatromillones de pobresen Chile: Actualizando la linea de pobreza. Estudios Publicos 109:1–48

Larrañaga (2009) Inequality, poverty, and social policy. OECD Social, Employment, and Migration Working Papers No. 85, OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/224516554144

Letelier L (2010) Descentralización del estado y terremoto: El caso de Chile. Rev Chilena de Administración Pública 15(16):19–38. doi:10.5354/0717-6759.2010.11206

Lomnitz C (1970) Casualties and behavior of populations during earthquakes. Bull Seismol Soc Am 60(4):1309–1313

Lomnitz LA (1971) Reciprocity of favours in the urban middle class of Chile. Stud Econ Anthropol AS7:93–106

Lomnitz LA (1988) Informal exchange networks in formal systems: a theoretical model. Am Anthropol 90(1):42–55

Lomnitz C (2004) Major earthquakes of Chile: a historical survey, 1. Seismol Res Lett 75(3):368–378. doi:10.1785/gssrl.75.3.368

Lomnitz LA, Sheinbaum D (2004) Trust, social networks, and the informal economy: a comparative analysis. Rev Sociol 10(1):5–26

Mella Polanco M (2012) Efectos sociales del terremoto en Chile y gestión política de la reconstrucción Durante el Gobierno de Sebastián Piñera (2010–2011). Rev Enfoques 10(16):19–46

OECD (2010) Latin American economic outlook 2011: How middle-class is Latin America? OECD, Washington DC. www.latameconomy.org/fileadmin/uploads/laeo/Documents/E-book_LEo2011-EN_entier.pdf. Accessed 4 Feb 2015

Pauchard A, Aguayo M, Peña E, Urrutia R (2005) Multiple effects of urbanization on the biodiversity of developing countries: the case of a fast-growing metropolitan area (Concepción-Chile). Biol Conserv 127:272–281

Pelling M (2003) The vulnerability of cities. Natural disasters and social resilience. Earthscan Publications, Oxon

Phillips B, Thomas D, Fothergill A, Blinn-Pike L (2010) Social vulnerability to disasters. CRC Press, Boca Raton

PNUD and Municipalidad de Talcahuano (2012) Guía Participativa de Orientaciones de Respuesta Frenta a Emergencias de Terremoto-Tsunami a Partir de la Experiencia de Talcahuano, Chile. PNUD, Santiago de Chile

Putnam R (2000) Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American Community. Simon & Schuster, New York. Kindle edition

Quezada J, Torrejón F, Jaque E, Fernández A, Belmonte A, Martinez C (2012) Comparación entre el Terremoto Mw = 8.8 del 27 de Febrero de 2010 y su Predecesor de 1835. Congreso Geológico Chileno 13:100–102

Rakodi C (1999) A capital assets framework for analysing household livelihood strategies: implications for policy. Dev Pol Rev 17:315–342. doi:10.1111/1467-7679.00090

Romero H, Vidal C (2010) Efectos ambientales de la urbanización de las cuencas de los ríos BíoBío y Andalién sobre los riesgos de inundación y anegamiento de la ciudad de Concepción. In: Pérez L, Hidalgo R (eds) Concepción metropolitano (AMC). Planes, procesos y proyectos. Pontificia Universidad Católica

Silbergeit V, Prezzi C (2012) Statistics of major Chilean earthquakes recurrence. Nat Haz 62:445–458

Solimano A (2011) Prosperity without equality: the Chilean Experience after the Pinochet Regime. http://www.andressolimano.com/andressolimano/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/growth-without-equality-chile-solimano-september-24-2011.pdf. Accessed on 31 July 2015

Solimano A (2012) Chile and the Neoliberal Trap. the Post-Pinochet experience. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York

Steffen W, Sanderson A, Tyson PD, Jäger J, Matson PA, Moore B III, Oldfield F, Richardson K, Schellnhuber HJ, Turner BL II, Wasson RJ (2004) Global change and the earth system: a planet under pressure. Springer, New York