Abstract

Disability arising from post-stroke cognitive impairment is a likely contributor to the poor quality of life (QoL) stroke survivors and their carers frequently experience, but this has not been summarily quantified. A systematic literature review and meta-analysis was completed examining the association between general and domain-specific post-stroke cognitive functioning and adult stroke survivor QoL, caregiver QoL, and caregiver burden. Five databases were systematically searched, and eligibility for inclusion, data extraction, and study quality were evaluated by two reviewers using a standardised protocol. Effects sizes (r) were estimated using a random effects model. Thirty-eight studies were identified, generating a sample of 7365 stroke survivors (median age 63.02 years, range 25–93) followed for 3 to 132 months post-stroke. Overall cognition (all domains combined) demonstrated a significant small to medium association with QoL, r = 0.23 (95% CI 0.18–0.28), p < 0.001. The cognitive domains of speed, attention, visuospatial, memory, and executive skills, but not language, also demonstrated a significant relationship with QoL. Regarding caregiver outcomes, 15 studies were identified resulting in a sample of 2421 caregivers (median age 58.12 years, range 18–82) followed for 3 to 84 months post-stroke. Stroke survivor overall cognitive ability again demonstrated a significant small to medium association with caregiver outcomes (QoL and burden combined), r = 0.17 (95% CI 0.10–0.24), p < 0.001. In conclusion, lower post-stroke cognitive performance is associated with significant reductions in stroke survivor QoL and poorer caregiver outcomes. Cognitive assessment is recommended early to identify those at risk and implement timely interventions to support both stroke survivors and their caregivers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Stroke is one of the leading causes worldwide of complex disability in adults (Adamson et al., 2004; Mendis, 2013; WHO, 2020), and stroke survivors frequently report lower quality of life (QoL) than age-matched controls (Aliyu et al., 2018; Goh et al., 2019). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines QoL as “individuals’ perceptions of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns”. (The WHOQOL Group, 1998). While there is no singular agreed definition of QoL, the concept is generally taken to refer to the capabilities and satisfaction individuals experience within domains such as physical, mental, and social functioning (Coons et al., 2000) and measures of QoL often include aspects of both functioning and perceptions and feelings about one’s life (Golomb et al., 2001). Not surprisingly, stroke severity and extent of disability have been shown to influence QoL (Sturm et al., 2004). Cognitive impairment is also increasingly recognised as a potential contributing factor to poor QoL (Barker-Collo et al., 2010a, b; Cumming et al., 2014; Verhoeven et al., 2011a, 2011b).

Cognitive impairment is a common consequence of stroke; two-thirds to three-quarters of stroke survivors experience cognitive difficulties depending on the timing and method of assessment (Jaillard et al., 2009; Jokinen et al., 2015; Renjen et al., 2015) and many identify support for cognition as a long-term unmet need (Andrew et al., 2014). The presence of either generalised and/or domain-specific impairment is highly predictive of chronic activity limitations and participation restrictions (Mole & Demeyere, 2020; Stolwyk et al., 2021; Watson et al., 2020). Therefore, it stands to reason that greater cognitive impairment may contribute to poorer QoL. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Watson et al. (2020) identified a significant relationship between several cognitive domains and QoL in individuals with acquired brain injuries. The review included domain-specific neuropsychological measures at variable stages of recovery. Studies using cognitive screening were not included, though these also may provide valuable information due to their widespread use. Moderator analysis to understand factors that may influence the association between stroke survivor cognition and outcome such as stroke survivor age and time post-stroke; quantifying the relationship between cognitive ability and QoL in a stroke survivor-only sample; and analysis using both screening and neuropsychological measures of cognition would be beneficial. Although cognitive screening measures are not as sensitive at detecting cognitive impairment as neuropsychological assessments (Jokinen et al., 2015), they are frequently used in research and clinical practice, and numerous international clinical guidelines for stroke care recommend that stroke survivors undergo cognitive screening followed by further neuropsychological evaluation if indicated (Canadian Stroke Best Practices, 2019; Royal College of Physicians, 2016; Stroke Foundation, 2021). Evaluation of screening measures can therefore be considered important for a more comprehensive synthesis of the research evidence, alongside evaluation of specific cognitive domains, which may have greater predictive power regarding outcomes, or may affect outcomes differently (Middleton et al., 2014; Nys et al., 2005), thereby informing biopsychosocial formulation. Another important factor to consider is the temporal relationship between cognition and outcome assessments. Concurrent assessment of stroke survivor cognition and outcome determines the association between the two variables at one point in time, while sequential assessment determines if cognitive performance earlier in stroke recovery is associated with outcome at a later time. Studies within this field vary with regards to concurrent versus sequential study designs, and delineating results between these approaches could help inform optimal timing of assessment.

Up to three-quarters of stroke survivors require assistance with their activities of daily living and receive informal care from family or friends (Dewey et al., 2002). Informal caregivers maintain a pivotal role in supporting stroke survivors in the community (Dewey et al., 2002; Di Carlo, 2009); however, this often comes at a cost (Rigby et al., 2009) referred to as caregiver burden (Montgomery et al., 1985). Caregiver burden effects 25–54% of carers (Rigby et al., 2009) and is associated with higher rates of anxiety and depression, poorer social and leisure time satisfaction, adverse effects on family relationships, increased mortality, and overall reduced quality of life (Anderson et al., 1995; Atteih et al., 2015; Haley et al., 2015; Parag et al., 2008; Schulz & Beach, 1999). Poorer cognitive functioning post-stroke may be associated with caregiver burden and QoL, but this association has limited empirical evaluation. A prior systematic literature review of caregiver burden following stroke included only five studies reporting stroke survivor cognition as a potential variable, and no clear association with caregiver burden emerged (Rigby et al., 2009). A more recent meta-analysis investigating variables that influence caregiver burden included only two studies that considered stroke survivor cognition as a variable (Zhu & Jiang, 2018), and again no conclusions could be drawn. This is potentially because the review focused on multiple predictors of caregiver burden without a specific focus on cognitive impairment. Therefore, a thorough examination of predictors of post-stroke caregiver burden with a particular emphasis on stroke survivor cognition is overdue. Again, the inclusion of both general and domain-specific cognitive assessments was considered important for a comprehensive evaluation of the literature, to firstly comment if stroke survivor cognition impacts on caregiver burden and secondly, if possible, evaluate if specific cognitive domains are associated with caregiver burden in different ways.

Aim

Our aim was to perform a systematic literature and meta-analysis to quantitatively evaluate the relationship between post-stroke cognitive ability and stroke survivor QoL, caregiver QoL, and caregiver burden. The review focused on both general cognitive screening and neuropsychological testing of specific cognitive domains (i.e., neglect, speed, attention, visuospatial skills, language, memory, and executive function). Relationships with stroke survivor QoL and caregiver outcomes (QoL and burden) were examined at least 3 months after stroke.

Method

Eligibility Criteria

Original research studies published in peer review journals quantitatively investigating the relationship between cognition, measured using standardised screening tools or formal neuropsychological assessment tools, and measures of stroke survivor or caregiver QoL or caregiver burden were included. Caregiver anxiety, depression, or general wellbeing were not considered to be measures of caregiver QoL. Measures of QoL and caregiver burden were required to have been collected at least 3 months post-stroke. Cognition was required to be measured at either the same time as QoL and caregiver burden (concurrent collection) or at a prior baseline assessment (sequential collection). Additional inclusion criteria were (i) adult participants (> 18 years old); (ii) diagnosis of stroke caused by either infarction or intracerebral or subarachnoid haemorrhage; (iii) use of validated measures of cognition, QoL, and caregiver burden; and (iv) published in English. Exclusion criteria were (i) cohorts with primary diagnoses other than stroke (including vascular dementia); (ii) mixed samples including participants with traumatic brain injury, transient ischaemic attack, or dementia, with no separate reporting of stroke-only data; (iii) case series or case studies; (iv) use of only self or informant-reported measures of cognition; and (v) review studies.

Information Sources

Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid PsycINFO, EBSCOhost CINAHL, Ovid Embase, and Elsevier Scopus were systematically searched with no restriction on the year of publication. Combinations of the following subject headings and key words were used across all databases: stroke, cerebrovascular, CVA, brain vascular, brain ischemia, ischemic, infarct, occlusion, thrombus, cerebellar, cerebral, intracranial, MCA, anterior circulation, basal ganglia, posterior circulation, haemorrhage, subarachnoid haemorrhage, haematoma, bleed, post-stroke, cognition, neuropsychology, executive function, attention, concentration, memory, perceptual, awareness, insight, speed, learning, recall, self-monitoring, organisation, disorder, dysfunction, impairment, deficit, ability, difficulties, quality of life, activities of daily living, institutionalisation, mortality, caregivers, caregiver burden, function, activity, outcome, participation, independence, limitation, restriction, and dementia (please see Supplementary materials for the full database search strategies). This resulted in a large volume of studies, and a separate systematic literature review and meta-analysis investigating the relationship between cognition and activity limitations and participation restrictions has been published elsewhere (Stolwyk et al., 2021). The following review focused on QoL and caregiver outcomes. The initial database search was conducted in March 2021 with an updated final search run on 29 May 2023. Reference lists from reviews and articles were also hand searched to identify other potentially relevant publications.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

The database search results were uploaded to the Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation), and duplicates were removed using the automated function. The eligibility assessment was performed independently by two researchers (TM and one trained research assistant BW, OZ, RK, CA, or SA) using a standardised protocol. Two researchers independently screened each title and abstract to assess the suitability for inclusion based on a checklist developed from the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by a third reviewer (RS). Publications considered eligible were independently reviewed in full text by two researchers (TM and either RS, JR, DW, DRH, BW, OZ). Disagreement was resolved by consensus, with a third author acting as arbitrator if an agreement could not be reached. For articles meeting the inclusion criteria, data on participants, study design, time since injury, cognition measures, outcome measures, and statistical analysis were extracted by TM, and the accuracy of the extraction and interpretation of effect directions was verified by DRH. In the updated 2023 search, the data were extracted by a research assistant (BW) and verified by TM. If the study had missing data, failed to report non-significant results, or the data were in a non-extractable format (e.g. regression weights), the corresponding author was contacted for additional information and/or clarification. If no response was received after two contact attempts either (1) the available data were extracted for inclusion in the review and the risk of reporting bias was acknowledged in the assessment of study quality; or (2) the study was excluded from the review. If the reviewers suspected that multiple articles may have been published using the same cohort, the authors were emailed for clarification. If there was no response, it was assumed that the articles represented a different cohort if sample size, follow-up period, and descriptive statistics differed.

Data Items

Independent Variable Measurement

Given the lack of international consensus regarding test classifications, a pragmatic approach was taken to categorise tests into cognitive domains for the purposes of analysis (see Table 1). This allocation was based on a combination of information sources, primarily (i) test publisher technical manuals, (ii) key texts in the field of neuropsychological assessment (e.g. Lezak, 2012), (iii) review articles, and (iv) categorisations used in previous similar reviews (Watson et al., 2020). In cases of inconsistency across these sources, the authors, all of whom are registered clinical neuropsychologists, made an executive decision based on the overall weight of evidence. Some published studies presented study-defined cognitive domains based on an aggregate of multiple tests which were not consistent with the Table 1 classification and could not be separated based on the available data (e.g. Barker-Collo et al., 2010b, Chahal et al., 2011, Passier et al., 2012). In this instance the data were included in the domain reported in the published study, with consensus from current study authors that this is the main domain represented by the aggregate score, and highlighted in Table 1 and 3 by an asterisk. The only exception was the aggregate factor named ‘non-linguistic cognition’ in Dvorak et al. (2021) which comprised of tests assessing multiple aspects of cognition which could not be classified into one domain and, therefore, was only included in the overall cognition analysis. When a study reported more than one measure within a cognitive domain (e.g. multiple measures of executive function), all results were combined by the meta-analysis software into a single measure of effect.

Outcome Measurement

Instruments were classified as QoL by author consensus (see Table 2) based on working definitions of the construct (The WHOQOL Group, 1998), instrument and item descriptions, and cross-checking with previous reviews (Geyh et al., 2007; von Steinbuechel et al., 2005; Watson et al., 2020). Instruments assessing caregiver burden were identified by measure and item descriptions and cross-checked in previous reviews (Rigby et al., 2009).

Quality Assessment

The methodological quality and risk of bias for each study were independently assessed by two authors (TM and either RS, JR, DW, or DRH) using a modified Quality in Prognostic Studies (Hayden et al., 2006, 2014). The QUIPS is a validated assessment of the quality of prognostic studies which could be easily adapted and applied to fit the purpose of the current review to include both prognostic and non-prognostic studies. The QUIPS rates methodological quality across six domains: (1) study population, (2) study attrition (completeness of data added for non-prognostic studies), (3) prognostic factor measurement (independent variable measurement for non-prognostic studies), (4) outcome measurement, (5) confounding measurement and account, and (6) analysis. Hayden et al. (2014) provide factors to consider for assessment of potential bias under each domain which are designed to be modified based on the research question This framework was used to develop a set of criteria for the present study (see Supplementary materials). Each criterion was rated on a 3-point scale from met, partly met, or not met/not enough evidence to determine if the criterion was met. Each study was rated as (i) low risk of bias if four to six domains were rated as ‘met’, one to two as ‘partly met’, and none were rated as ‘not met’; (ii) moderate risk of bias if at least three domains were rated as ‘met’, two to three were rated as ‘partly met’, and a maximum of one rated as ‘not met’; and (iii) high risk of bias if four or more domains were ‘partly met’ or two or more domains were ‘not met’.

Effect Measures and Synthesis Methods

Data on the association (r) between cognition and QoL outcomes in stroke survivors and caregiver QoL and burden were extracted in the available format (e.g. correlations and sample sizes, odds ratios, means, standard mean differences, and sample sizes, cohort 2 × 2 events) and entered into Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 3 (Borenstein et al. 1994). A random effects mixed model was used to compute effect sizes with the magnitude of the correlation. A correlation as a measure of effect was chosen because the review explored a relationship between two continuous variables, and it was the most reported measure of effect in the studies meeting inclusion criteria. Effect sizes were categorised as follows: small > 0.10, medium > 0.30, and large > 0.50 (Cohen, 1988). Effect sizes were assigned a positive value if superior cognition was associated with enhanced QoL or reduced caregiver burden. While the majority of studies measured cognition as a continuous variable, five studies classified cognition as intact/impaired using a cut score (Hotter et al., 2018; Kwa et al., 1996; Patel et al., 2007; Meyer et al. (2010); Scott et al., 2008). Results from these studies were converted to correlations for the purposes of the meta-analysis.

Heterogeneity across studies was reported using Q as a total variance statistic, I2 as a relative measure of the proportion of variance (Higgins & Thompson, 2002), interpreted as low (25%), moderate (50%), or high (75%) (Higgins et al., 2003), and tau2 (τ2) as an absolute measure of the between-study variance. The risk of publication bias was assessed using visual inspection of funnel plots and Egger’s regression test (one-tailed, alpha < 0.05 suggesting publication bias).

Following a main effects analysis investigating the relationship between overall cognition and stroke survivor QoL, subgroup analyses were completed separately for each cognitive domain (visuospatial, speed, attention, language, memory, executive function, and cognitive screening). Measures of neglect and visuospatial skills were combined into visuospatial skills due to a small number of studies measuring neglect that met inclusion criteria. The majority of the studies investigating caregiver outcomes only used cognitive screening instruments, prohibiting subgroup analysis of cognitive domains.

Moderator variables were identified a priori and included factors previously identified in the research literature as having a potential impact on post-stroke cognitive outcomes. Moderator analysis of categorical variables was conducted using the Q-statistic (alpha = 0.05). Analyses included study quality (low vs moderate/high risk of bias) to explore if lower quality studies are resulting in an overestimation of the overall effect, and the time cognition was measured (concurrent versus sequential assessment). Concurrent assessment of stroke survivor cognition and outcome determines the association between the two variables at one point in time. Sequential assessment determines if cognitive performance earlier in stroke recovery is associated with outcome at a later time (i.e. can be used to predict outcome). Continuous moderator variables were examined using meta-regression and included the mean age of the stroke survivor (to comment whether age influences the relationship between cognition and QoL) and mean time since injury (to comment if the relationship between cognition and outcome changes over time). For caregiver outcomes, the mean age of the caregiver was also evaluated as a potential moderator variable.

Reporting Bias and Certainty Assessment

The study methodology was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO ID: CRD42018089092) in March 2018 to minimise the risk of the dissemination of research findings being influenced by the nature and direction of results. The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) framework (Atkins et al., 2004; Balshem et al., 2011; Guyatt et al., 2008) was used to rate the confidence that the estimated effect between cognition, and stroke survivor QoL and caregiver outcomes (QoL and burden) is correct. All authors were involved in rating the quality and certainty across the 5 GRADE domains (risk of bias/study limitation, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, and publication bias), with final ratings labelled as very low, low, moderate, or high based on consensus.

Results

Study Selection

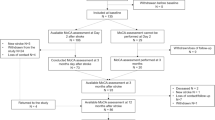

The selection process is depicted in Fig. 1 and resulted in 50 articles eligible for inclusion. Thirty-eight studies examined the relationship between cognition and QoL of stroke survivors (Table 3). Fifteen studies investigated the relationship between stroke survivor cognitive functioning and caregiver burden and/or caregiver QoL (Table 4). Three studies reported both stroke survivor and caregiver outcomes (Hotter et al., 2018; Khalid et al., 2016; Scott et al., 2008) and were included in both subgroup analyses. Eleven of the 33 authors contacted provided sufficient additional data to include the study in the current review (identifiable by notation ‘AD’ in Table 3 and 4). The studies comprised prognostic or observational cohort designs, conducted across 24 countries. The largest number of studies originated in the Netherlands (N = 10) followed by the USA (N = 5) and Hong Kong (N = 4). An additional 28 studies almost met the inclusion criteria. These ‘near miss’ studies, the findings, and reasons for exclusion are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Study Quality

Study quality was variable. Regarding stroke survivor QoL outcomes, 12 studies were rated as having an overall low risk of bias, 20 a moderate risk of bias, and six a high risk of bias (see Table 5). Regarding caregiver outcomes, seven studies were rated as low, five as moderate, and three as a high risk of bias (see Table 5). The most common risks were due to excessive study attrition/incompleteness of data, incomplete description of the study population, and lack of consideration of confounding variables. The less common risks of bias are related to inadequate measurement of prognostic factors/independent variables (cognition) and outcomes. Lower ratings in these domains were usually associated with the use of cut-off scores for continuous variables.

Study Characteristics

The characteristics of the studies investigating the relationship between stroke survivor cognition and their QoL and caregiver outcomes (QoL and burden) are presented in Table 6.

Cognition and Quality of Life in Stroke Survivors

In the 38 studies, overall reduced cognitive functioning (all neuropsychological tests and screening measures combined) had a significant small to medium association with diminished QoL, r = 0.23 (95% CI 0.18–0.28), p < 0.001 (see Fig. 2). Inspection of the funnel plot revealed significant asymmetry (Egger’s intercept = 2.81, p < 0.001, one-tailed). While there was a lack of small studies with negative findings, there appeared to be even more random variation in the large studies. This heterogeneity was explored using meta-regression where the sample size was not a significant variable (β = − 0.0001, SE = 0.0001, z = − 1.66, p = 0.10). Heterogeneity was significant, I2 = 92%, Q (37) = 442.63, p < 0.001; τ2 = 0.02.

The observed main effect was moderated by study quality, with studies rated as low risk of bias (N = 12) demonstrating larger effect sizes, r = 0.30 (95% CI 0.23–0.37), than studies rated as moderate/high risk of bias (N = 26), r = 0.19 (95% CI 0.14–0.24), p = 0.013. The mean age of the stroke survivor, mean time since injury, and timing of the cognitive assessment (i.e. concurrent versus sequential) were not significant moderators (see Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). As noted within the methods section, the majority of included studies measured cognition as a continuous variable, with only five studies using cut points to infer impairment on some measures. Visual inspection of effect sizes statistics (Fig. 2) of these five studies did not reveal any discernible differences in the pattern of results compared to the rest of the included studies. This also applies to cognitive domain-specific analyses (Fig. 3) and caregiver outcome analyses (Fig. 4) below.

The relationship between QoL and individual cognitive domains is depicted in Fig. 3. Two studies were unable to be included in the cognitive domain subgroup analysis: Scott et al. (2008) investigated global cognition (i.e. multiple neuropsychological tests combined) and Jonkman et al. (1998) investigated a decrease in intellectual function (i.e. global cognition in comparison to premorbid estimates of cognitive functioning). All cognitive domains, except language, demonstrated a small to medium significant relationship with QoL outcomes for stroke survivors. Those with poorer speed, attention, visuospatial skills, memory, executive skills, and poorer performances on general cognitive screening exhibited lower QoL. Risk of bias (low versus moderate/high), timing of assessment (i.e. concurrent versus sequential), mean age, and mean time since injury did not significantly moderate the relationship between any cognitive domains (i.e. speed, attention, visuospatial, language, memory, or executive function) and QoL in stroke survivors.

Stroke Survivor Cognitive Function and Caregiver Outcomes

Fifteen studies reported data on caregiver outcomes. Caro and colleagues (2017), Green and King (2010), and Visser-Meily and colleagues (2005) investigated both caregiver burden and caregiver QoL. Therefore, data were available for ten studies investigating burden and eight investigating caregiver QoL. Given the small number of studies, caregiver outcomes (caregiver burden and caregiver QoL) were primarily examined combined, before also examined separately. Cognition was primarily assessed using cognitive screening instruments (80.0%, 12/15 studies). Two studies also assessed language function (Hotter et al., 2018; Vincent et al., 2009), one visuospatial skill (Vincent et al., 2009), one executive skill (Wu et al., 2019), and one investigated global cognition based on neuropsychological assessment (Scott et al., 2008). In sum, there was insufficient power (Jackson & Turner, 2017) to complete separate cognitive domain subgroup analysis for caregiver outcomes.

Overall diminished cognitive functioning (all neuropsychological tests and screening measures combined) had a significant small to medium association with poorer overall caregiver outcome (caregiver burden and QoL combined), r = 0.17 (95% CI 0.10–0.24), p < 0.001 (see Fig. 4). Inspection of funnel plots revealed reasonable symmetry (Egger’s intercept = − 0.25, p = 0.42, one-tailed). Heterogeneity was significant, I2 = 64%, Q (14) = 38.62, p < 0.001; τ2 = 0.01. The effect was moderated by study quality, with studies rated as low risk of bias (N = 8) reporting higher effect sizes, r = 0.22 (95% CI 0.15–0.30) than those rated as moderate/high risk of bias (N = 7), r = 0.07 (95% CI = − 0.05–0.19), p = 0.038. The time point that cognition was assessed (concurrent vs sequential), mean stroke survivor age, mean caregiver age, or mean time since injury were not significant moderators (see Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). Finally, effect sizes were similar when caregiver outcomes (i.e. caregiver burden and caregiver QoL) were analysed separately. Poorer cognitive functioning demonstrated a small to medium significant association with higher caregiver burden, r = 0.17 (95% CI 0.06–0.29), p < 0.001 and lower caregiver QoL, r = 0.14 (95% CI 0.06–0.21), p < 0.001.

Reporting Bias and Certainty Assessment

The GRADE framework was used to rate the confidence in the observed effects between cognition and stroke survivor QoL and caregiver outcomes. As this systematic review included observational studies, the starting level of confidence was rated as low. No points were deducted for imprecision, indirectness, or publication bias, or risk of bias. As noted above, moderator analyses revealed that high-quality studies demonstrate a larger effect than low-quality studies. However, there was significant heterogeneity which reduced our confidence based on inconsistency. Overall, the confidence in the overall effect between cognition and stroke survivor QoL and caregiver outcomes was rated as Low.

Discussion

This systematic literature review and meta-analysis investigated the association between adult stroke survivor cognitive functioning and stroke survivor QoL, caregiver QoL and caregiver burden at least 3 months post-stroke. The review identified 50 studies, spanning the last two decades and 24 countries worldwide. Thirty-eight of the studies reported on the association between cognition and stroke survivor QoL, and 15 reported on the association between cognition and caregiver outcomes. Reduced post-stroke cognition was significantly associated with poorer QoL of stroke survivors and their informal carers and higher caregiver burden, regardless of the mean age of the stroke survivor or caregiver, mean time since injury, or the timing of the cognitive assessments.

There was a small to medium but significant association (r = 0.23) between stroke survivor cognition and QoL. Consistent with previous reviews (Watson et al., 2020), individuals with reduced cognitive performance reported lower QoL. That finding has now been replicated utilising a larger number of studies specifically focusing on the stroke population in later stages of recovery (> 3 months) and including both screening and neuropsychological measures of cognition. The finding that cognition is associated with QoL is consistent with observations in other populations including individuals diagnosed with various neurological conditions (Gorgoraptis et al., 2019; Lawson et al., 2014; Mitchell et al., 2010) and older adults (Borowiak & Kostka, 2004; Pan et al., 2015).

Subgroup analysis of multiple cognitive domains found that speed, attention, visuospatial, memory, and executive skills were all important in determining QoL in stroke survivors. Stroke survivors with reduced performance in these domains reported a lower QoL. No significant association was observed between language and QoL. This was surprising as the increasing severity of aphasia is negatively correlated with QoL (Hilari et al., 2012). However, in the current review, measures of language were comprised of basic expressive and receptive function assessments (e.g. Boston Naming Test, Token Test, and language index from the RBANS) which may not capture pragmatic communication difficulties. One finding suggests that language production, rather than comprehension, may have a stronger association with stroke survivor QoL (Dvorak et al., 2021). Furthermore, from a methodological perspective, individuals with greater communication impairments are frequently excluded from studies due to difficulties participating in cognitive testing, completing patient-reported outcome measures, or engaging in informed consent procedures (Brady et al., 2013). It is indeed important to consider the validity of comprehensive neuropsychological assessment, particularly in people with severe language comprehension impairment (Crivelli et al., 2023). To wit, of the eight studies included in this review that assessed language function, five reported procedures for managing individuals with aphasia which included omitting verbal assessments or excluding this population altogether. Aphasia post-stroke is common (16–30% at follow up; Flowers et al. (2016)) and stroke survivors with aphasia often experience other cognitive difficulties (Fonseca et al., 2019). Future research should aim to accommodate individuals with aphasia to provide a more representative sample of stroke survivors.

Cognitive screening measures also demonstrated a significant association with QoL. Cognitive screening tools are widely used in many clinical and research settings, as they are quick to administer, feasible to embed in clinical practice and research protocols, and are generally effective in detecting global post-stroke cognitive difficulties. The observed association emphasises the importance of advocating for cognitive screening as part of routine care to identify reduced post-stroke cognitive functioning and those at risk of poor outcomes. Nevertheless, we also recommend further comprehensive neuropsychological assessment of stroke survivors who present with low cognitive performance on screening instruments or those with subjective (van Rijsbergen et al., 2014) or informant-reported cognitive complaints. This is because many cognitive screening tools have the potential to under- or over-estimate cognition for those with low or high premorbid cognitive function; fail to assess low prevalence stroke-related cognitive impairments (e.g. prosopagnosia); and many are unable to provide a profile of intact and impaired cognitive domains (i.e. produce just one global score/cut-point; Jokinen et al., 2015; Stolwyk et al., 2014). Comprehensive neuropsychological assessments address many of these aforementioned limitations by producing a detailed cognitive profile of cognitive strengths and weaknesses that can be interpreted not only in relation to age-related peers but also compared to a person’s estimated premorbid cognitive function. This provides a more informative characterisation of how a recent stroke may have impacted a person’s specific cognitive functions, which can, in turn, be used as part of a broader biopsychological formulation to address diagnostic considerations and inform ongoing management and further rehabilitation. There are many evidence-based neuropsychological rehabilitation interventions available (Rogers et al., 2018) representing an opportunity to improve patient outcomes. Selecting the best intervention, however, would rely on a thorough understanding of the stroke survivor’s cognitive strengths and weaknesses.

Regarding caregiver outcomes, meta-analysis revealed a small to medium association between stroke survivor cognitive functioning and caregiver outcomes (r = 0.17). Caregivers reported lower QoL and higher caregiver burden when providing support to stroke survivors with reduced cognitive ability. In the current review, we identified 15 studies that met inclusion criteria; 10 reported caregiver burden and eight caregiver QoL data, providing a synthesis of evidence from a larger number of studies than previous reviews (Rigby et al., 2009; Zhu & Jiang, 2018). The majority of studies investigating caregiver outcomes (80%) utilised cognitive screening instruments to measure stroke survivor cognition, as opposed to comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation, and so cognitive subdomain analysis was not possible.

This review provides evidence that the cognition of stroke survivors can impact caregiver outcomes. Further research is required to explore this association in more detail using comprehensive neuropsychological assessment to allow for domain-specific analysis which was not possible based on currently available studies. It is possible that some cognitive domains may be more predictive of caregiver outcomes than others due to unique challenges experienced in managing and supporting the stroke survivor. It could be hypothesised, for example, that cognitive functions which particularly impact personality and behaviour (e.g. executive functions and social cognition) may be particularly difficult for caregivers to manage.

In clinical practice, caregivers often receive information and support on managing the physical aspects of stroke recovery, particularly early post-stroke when the focus is on leaving the hospital. However, in an interview-based study, caregivers identified managing cognitive, emotional, and behaviour changes as one of the primary problems in the first-month post-stroke and reported that they were initially unaware or underestimated how cognitive difficulties would impact on safety (e.g. falls; Grant et al., 2004). The current review demonstrates that poorer cognitive functioning post-stroke negatively impacts the caregiver experience, further highlighting the importance of providing caregivers with early education, training, and ongoing access to services to help manage cognitive changes post-stroke.

The current meta-analysis found that study quality moderated the relationship between stroke-survivor cognition, and both stroke-survivor QoL and caregiver outcomes (QoL and burden). Low risk of bias studies demonstrated larger effect sizes than those rated as moderate to high risk of bias; suggesting that with methodologically rigorous study designs, the relationships are more likely to be demonstrated. As lower-quality studies outnumbered higher-quality studies, the current reported association may underestimate the true overall effect. The strength of the relationship between stroke survivor cognitive ability and either stroke survivor QoL or caregiver outcomes was not significantly moderated by mean stroke survivor age, mean caregiver age, mean time point that cognition was assessed (concurrent vs sequential), or mean time since injury. This indicates that cognition is an important variable to consider across age groups of stroke survivors and caregivers and across stages of stroke recovery. It is important to note; however, that we examined these factors as means within each study, and it was not possible to conduct an individual patient data meta-analysis of trajectories of functioning, which may have influenced study findings (see Lo et al., 2022). Overall, these findings highlight the importance of providing ongoing short-term and long-term support to stroke survivors with cognitive difficulties and their informal caregivers to optimise their QoL and mitigate caregiver burden.

Limitations

Several limitations in the current review are acknowledged. Firstly, the initial aim of this review was to investigate the relationship between cognition and multiple outcomes including quality of life, ADL, participation, institutionalisation, mortality, caregiver burden, and dementia diagnosis. An initial search in March 2021 resulted in a large volume of publications and a lengthy synthesis process that was found to be beyond the scope of a single review and the focus was subsequently narrowed. Therefore, database searches of desired outcomes were repeated at later dates to capture any advancement in the field, ADL and participation outcomes were published elsewhere (Stolwyk et al., 2021), and QoL and caregiver burden were presented. The final search for the current review was completed in May 2023. The authors acknowledge that additional work may have become available subsequently and recommend an ongoing review of literature to update the knowledge base.

Second, while the review identified associations between post-stroke cognition and QoL and caregiver outcomes, these associations do not infer causation. Based on current evidence, we cannot conclude with high certainty that cognition directly impacts these outcomes, as opposed to sharing variance with other variables that may be more directly influencing QoL and burden. For example, there is high-comorbidity between stroke-related cognitive and physical impairments. While some studies in this review reported a unique association between cognition and QoL using regression modelling, other studies using simple correlations were not able to control for potential shared variance with other factors. Future studies using regression-based approaches and including potential confounds such as overall stroke severity and physical impairment are recommended. Studies investigating if ameliorating cognitive difficulties results in improved QoL and caregiver outcomes may also further shed light on this relationship. Further, given the observational nature of study designs; the quality of the studies available (32% and 53% rated as low risk of bias for stroke survivor and caregiver outcomes, respectively), and unexplained variability in findings across studies, the confidence in the effect identified in this study is limited. This is reflected in the GRADE ratings (low), and therefore, the recommendations and conclusions are provided with this in mind.

Third, a wide range of tests was used to assess cognition with no clear consensus within the literature on which test should be used to assess a particular cognitive domain. This is likely due to the multifaceted nature of several cognitive domains and the fact that most neuropsychological tests in fact measure multiple cognitive processes. For example, executive functions refer to a set of processes required for complex and goal-directed behaviour, including planning, set-shifting, problem-solving, reasoning, and inhibitory control (Diamond, 2013). There is significant overlap with other cognitive domains such as attention and a range of measures are generally required to be administered to capture this constellation of skills. The authors took a pragmatic approach to test categorisation as described in the Method section, and it is recognised that there will be some differences of opinion on decisions made. It is also recognised that the tests targeting some domains (e.g. visuospatial) are heterogeneous and in fact measure a range of more discrete skills, including neglect, object recognition and visual abstract reasoning. Even tests considered ‘purer’ measures of specific cognitive domains tend to differ in terms of the motor and sensory skills required to complete them. Further delineation of these cognitive constructs in future research is warranted in addition to selecting the most ‘process pure’ tasks where possible and acknowledging the inherent multifaceted nature of our cognitive measures (Kessels, 2019). Further, some authors grouped the same measures under different cognitive domains, reporting only aggregate scores of multiple tests which could not be separated (as denoted by the asterisk in Table 1) or used test batteries. For example, phonemic verbal fluency was grouped with assessments of language by some authors and executive skills by others. If the data for each test could not be separated, the current review identified the domain most closely represented based on classification by the published study and agreement by the research team; this method may result in a less delineation of cognitive domains. A lack of consensus on cognitive test selection and interpretation likely accounts for some of the variability observed across studies (Stolwyk et al., 2021). To increase the interpretability and generalisability of findings, the creation and use of consensus-based assessments and cognitive domain classifications are recommended. In addition, the current review did not include studies utilising measures of social cognition, meta-cognitive skills, or ecologically-based measures of cognition to be able to comment on their impact on stroke survivor or caregiver outcomes (i.e. QoL, burden). It is possible that ecologically-based measures may be more predictive of outcomes and inform targeted interventions (Hogan et al., 2023). Social cognition may also be important in predicting quality of life due to its known impact on emotion processing, social perception, and interpersonal relationships (Adams et al., 2019). It is recommended that future studies consider the inclusion of these tests, in additional to traditional neuropsychological measures, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the support required for stroke survivors and their carers.

Similarly, studies utilised a wide range of QoL measures which vary widely in the domains encompassed by each instrument (e.g. physical function, role activities, psychological well-being, social functioning, cognitive functioning, and health perceptions). The lack of consensus and standardisation in this field has been identified and critiqued previously (Geyh et al., 2007; Salter et al., 2008) and the differences amongst the QoL measures also likely contributed to some of the variability across studies. The WHO definition of QoL as the individuals’ perceptions of their position in life within their context, goals, and expectations should be in the forefront when selecting QoL instruments to measure outcomes, to avoid merely assessing the presence of impairments (mobility, ADL), symptoms or participation restrictions, but the individual’s satisfaction and perception of their life in relation to their physical, occupational, psychological, and social functioning. With regards to our specific research question, only some studies used a QoL measure containing cognition-related items (e.g. SSQoL, WHOQoL-BREF), with many other measures limited to physical and/or mental-health items (e.g. EuroQoL, SF-36). This may have led to some underestimation of the association between cognition and QoL in our analyses. To optimise methodological rigour, future studies in this field should consider QoL measures that include cognition-related items. There was relatively more consistency in the caregiver burden instruments. Similar to the work within the traumatic brain injury literature (Honan et al., 2019), guidelines and recommendations for test selection and outcome measurement would be beneficial in the stroke population to improve synthesis of evidence and provide stronger and more meaningful clinical and research recommendations.

Finally, our review identified that, overwhelmingly, cognitive screening instruments are used in the literature to measure cognitive functioning. Almost 60% of studies investigating stroke survivor QoL outcomes relied on cognitive screening instruments, and an even larger proportion relied on cognitive screening (80%) when investigating caregiver outcomes. In the context of screening instruments not being as sensitive as a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment to detect impairment and providing a broad overview of cognition with no specific areas for intervention, the clinical recommendations that can be made based on cognitive screening results are limited. Nonetheless, post-stroke cognition is an important variable to consider when identifying the risk of poor outcomes, and interventions and supports are required for the stroke survivor and their informal caregivers. We suggest that neuropsychological rehabilitation interventions should be person-centred and embedded in the everyday experience of the individual, targeting life roles that have the most impact on QoL and incorporating caregiver support and training as a core part of the intervention.

Conclusion

Predictors of outcome following stroke have historically relied upon physical measurements of stroke severity. The current review provides Level 1 evidence (OCEBM) that post-stroke cognition is not only associated with stroke survivor QoL but also the outcomes of their informal caregivers. Increased clinician awareness of the importance of cognition in determining outcomes is needed, along with embedding early and ongoing cognitive assessment of all stroke survivors within services to inform the provision of support, monitoring, and interventions aimed at stroke survivors and their caregivers. While the current review provides evidence that cognition is associated with stroke survivor QoL and caregiver outcomes (QoL and burden), the efficacy of neuropsychological rehabilitation in improving QoL outcomes and reducing caregiver burden requires further research.

Other information

Registration and Protocol

The current systematic literature review and meta-analysis was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Page et al., 2021). Protocol details for the review were registered with the online International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO ID: CRD42018089092) and can be accessed from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018089092.

The original protocol database search included multiple outcomes which resulted in a large volume of studies deemed beyond the scope of a single review. Therefore, the relationship between cognition and ADL and participation outcomes was published elsewhere (Stolwyk et al., 2021), and this review focuses on QOL and caregiver outcomes. Outcomes that were excluded are outlined in Fig. 1. Given the large volume of studies, the search was updated on 29th May 2023.

Availability of Data and Material

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Abzhandadze, T., Forsberg-Wärleby, G., Holmegaard, L., Redfors, P., Jern, C., Blomstrand, C., & Jood, K. (2017). Life satisfaction in spouses of stroke survivors and control subjects: A 7-year follow-up of participants in the Sahlgrenska Academy study on ischaemic stroke. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 49(7), 550–557. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2242

Adamit, T., Maeir, A., Ben Assayag, E., Bornstein, N. M., Korczyn, A. D., & Katz, N. (2015). Impact of first-ever mild stroke on participation at 3 and 6 month post-event: The TABASCO study. Disability & Rehabilitation, 37(8), 667–673. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.923523

Adams, A. G., Schweitzer, D., Molenberghs, P., & Henry, J. D. (2019). A meta-analytic review of social cognitive function following stroke. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 102, 400–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.03.011

Adamson, J., Beswick, A., & Ebrahim, S. (2004). Is stroke the most common cause of disability? Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases, 13(4), 171–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2004.06.003

Ahlsiö, B., Britton, M., Murray, V., & Theorell, T. (1984). Disablement and quality of life after stroke. Stroke, 15(5), 886–890. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.15.5.886

Ahmed, T., Kumar, R., & Bahurupi, Y. (2020). Factors affecting quality of life among post-stroke patients in the Sub-Himalayan region. Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice, 11(4), 616–622. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1716927

Akpalu, A., Calys-Tagoe, B. N., & Kwei-Nsoro, R. N. (2018). The effect of cognitive impairment on the health-related quality of life among stroke survivors at a major referral hospital in Ghana. West African Journal of Medicine, 35(3), 199–203.

Aliyu, S., Ibrahim, A., Saidu, H., & Owolabi, L. (2018). Determinants of health-related quality of life in stroke survivors in Kano, Northwest Nigeria. Journal of Medicine in the Tropics, 20(1), 11–16. https://doi.org/10.4103/jomt.jomt_26_17

Anderson, C. S., Linto, J., & Stewart-Wynne, E. G. (1995). A population-based assessment of the impact and burden of caregiving for long-term stroke survivors. Stroke, 26(5), 843–849. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.26.5.843

Andrew, N. E., Kilkenny, M., Naylor, R., Purvis, T., Lalor, E., Moloczij, N., & Cadilhac, D. A. (2014). Understanding long-term unmet needs in Australian survivors of stroke. International Journal of Stroke, 9, 106–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijs.12325

Atkins, D., Best, D., Briss, P. A., Eccles, M., Falck-Ytter, Y., Flottorp, S., Guyatt, G. H., Harbour, R. T., Haugh, M. C., Henry, D., Hill, S., Jaeschke, R., Leng, G., Liberati, A., Magrini, N., Mason, J., Middleton, P, Mrukowicz, J., O’Connell, D., Oxman, A. D., . . . , & Zaza, S. (2004). Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ, 328(7454), 1490–1488. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490

Atteih, S., Mellon, L., Hall, P., Brewer, L., Horgan, F., Williams, D., & Hickey, A. (2015). Implications of stroke for caregiver outcomes: Findings from the ASPIRE-S study. International Journal of Stroke, 10(6), 918–923. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijs.12535

Baddleley, A., Emslie, H., & Nimmo-Smith, I. (1994). Doors and People. Thames Valley Test Company.

Baek, M. J., Kim, H. J., & Kim, S. (2012). Comparison between the Story Recall Test and the Word-List Learning Test in Korean patients with mild cognitive impairment and early stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 34(4), 396–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803395.2011.645020

Bakas, T., & Champion, V. (1999). Development and psychometric testing of the Bakas Caregiving Outcomes Scale. Nursing Research, 48(5), 250–259. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-199909000-00005

Bakas, T., Champion, V., Perkins, S. M., Farran, C. J., & Williams, L. S. (2006). Psychometric testing of the revised 15-item Bakas Caregiving Outcomes Scale. Nursing Research, 55(5), 346–355. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200609000-00007

Balshem, H., Helfand, M., Schünemann, H. J., Oxman, A. D., Kunz, R., Brozek, J., Vist, G. E., Falck-Ytter, Y., Meerpohl, J., Norris, S., & Guyatt, G. H. (2011). GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64(4), 401–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015

Barker-Collo, S., Feigin, V. L., Parag, V., Lawes, C. M., & Senior, H. (2010b). Auckland Stroke Outcomes Study. Part 2: Cognition and functional outcomes 5 years poststroke. Neurology, 75(18), 1608–1616. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181fb44c8

Barker-Collo, S., Feigin, V., Lawes, C., Senior, H., & Parag, V. (2010a). Natural history of attention deficits and their influence on functional recovery from acute stages to 6 months after stroke. Neuroepidemiology, 35(4), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1159/000319894

Bédard, M., Molloy, D. W., Squire, L., Dubois, S., Lever, J. A., & O’Donnell, M. (2001). The Zarit burden interview: A new short version and screening version. The Gerontologist, 41(5), 652–657. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/41.5.652

Benton, A. L., Abigail, B., Sivan, A. B., Hamsher, K. d., Varney, N. R., & Spreen, O. (1994). Contributions to neuropsychological assessment: A clinical manual: Oxford University Press.

Benton, A. L. (1945). A visual retention test for clinical use. Archives of Neurology & Psychiatry, 54(3), 212–216. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneurpsyc.1945.02300090051008

Bergner, M., Bobbitt, R. A., Carter, W. B., & Gilson, B. S. (1981). The sickness impact profile: Development and final revision of a health status measure. Medical Care, 787–805. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198108000-00001.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., Higgins, J., & Rothstein, H. (1994) Comprehensive meta-analysis (Version 3.3.070). Biostat: Englewood, NJ USA.

Boosman, H., Schepers, V. P. M., Post, M. W. M., & Visser-Meily, J. M. A. (2011). Social activity contributes independently to life satisfaction three years post stroke. Clinical Rehabilitation, 25(5), 460–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215510388314

Borowiak, E., & Kostka, T. (2004). Predictors of quality of life in older people living at home and in institutions. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 16(3), 212–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03327386

Bouffioulx, É., Arnould, C., & Thonnard, J.-L. (2008). Satis-stroke: A satisfaction measure of activities and participation in the actual environmental experienced by patients with chronic stroke. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 40(10), 836–843. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-0272

Bouffioulx, É., Arnould, C., & Thonnard, J.-L. (2011). Satisfaction with activity and participation and its relationships with body functions, activities, or environmental factors in stroke patients. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 92(9), 1404–1410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2011.03.031

Brady, M. C., Fredrick, A., & Williams, B. (2013). People with aphasia: Capacity to consent, research participation and intervention inequalities. International Journal of Stroke, 8(3), 193–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00900.x

Brandt, J., Spencer, M., & Folstein, M. (1988). The telephone interview for cognitive status. Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsychology, and Behavioral Neurology, 1(2), 111–117.

Bugge, C., Hagen, S., & Alexander, H. (2001). Measuring stroke patients’ health status in the early post-stroke phase using the SF36. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 38(3), 319–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7489(00)00066-3

Burgess, P. W., & Shallice, T. (1997). The Hayling and Brixton Tests. Thames Valley Test Company: Bury St Edmonds, UK.

Canadian Stroke Best Practices. (2019). Canadian best practice recommendations for stroke care: Mood, cognition and fatigue following stroke. 6th. Retrieved from https://www.strokebestpractices.ca/recommendations/mood-cognition-and-fatigue-following-stroke

Caro, C. C., Mendes, P. V., Costa, J. D., Nock, L. J., & Cruz, D. M. (2017). Independence and cognition post-stroke and its relationship to burden and quality of life of family caregivers. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 24(3), 194–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749357.2016.1234224

Chahal, N., Barker-Collo, S., & Feigin, V. (2011). Cognitive and functional outcomes of 5-year subarachnoid haemorrhage survivors: Comparison to matched healthy controls. Neuroepidemiology, 37(1), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1159/000328647

Chang, W. H., Sohn, M. K., Lee, J., Kim, D. Y., Lee, S.-G., Shin, Y.-I., Oh, G.-J., Lee, Y.-S., Joo, M. C., Han, E. Y., Kang, C., & Kim, Y.-H. (2016). Predictors of functional level and quality of life at 6 months after a first-ever stroke: The KOSCO study. Journal of Neurology, 263(6), 1166–1177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-016-8119-y

Chen, Y., Lu, J., Wong, K. S., Mok, V. C. T., Ungvari, G. S., & Tang, W. K. (2010). Health-related quality of life in the family caregivers of stroke survivors. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 33(3), 232–237. https://doi.org/10.1097/MRR.0b013e328338b04b

Chiu, H., Lee, H.-C.B., Chung, W. S., & Kwong, P. K. (1994). Reliability and validity of the Cantonese version of Mini-Mental State Examination-A preliminary study. Hong Kong Journal of Psychiatry, 4, 25–28.

Choi-Kwon, S., Kim, H.-S., Kwon, S. U., & Kim, J. S. (2005). Factors affecting the burden on caregivers of stroke survivors in South Korea. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 86(5), 1043–1048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2004.09.013

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Colarusso, R. P., & Hammill, D. D. (1972). Motor-free visual perception test. Academic Therapy Publications: Novato, CA USA.

Coons, S. J., Rao, S., Keininger, D. L., & Hays, R. D. (2000). A comparative review of generic quality-of-life instruments. PharmacoEconomics, 17(1), 13–35. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200017010-00002

Crivelli, D., Spinosa, C., Angelillo, M. T., & Balconi, M. (2023). The influence of language comprehension proficiency on assessment of global cognitive impairment following Acquired Brain Injury: A comparison between MMSE, MoCA and CASP batteries. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult, 30(5), 546–551. https://doi.org/10.1080/23279095.2021.1966430

Cumming, T. B., Brodtmann, A., Darby, D., & Bernhardt, J. (2014). The importance of cognition to quality of life after stroke. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 77(5), 374–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.08.009

D’Aniello, G. E., Scarpina, F., Mauro, A., Mori, I., Castelnuovo, G., Bigoni, M., Baudo, S., & Molinari, E. (2014). Characteristics of anxiety and psychological well-being in chronic post-stroke patients. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 338(1), 191–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2014.01.005

De Renzi, A., & Vignolo, L. A. (1962). Token test: A sensitive test to detect receptive disturbances in aphasics. Brain, 85, 665–678. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/85.4.665

Delis, D. C., Kaplan, E., & Kramer, J. H. (2001). Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D–KEFS). APA PsycTests.

Devlin, N. J., & Brooks, R. (2017). EQ-5D and the EuroQol group: Past, present and future. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 15(2), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-017-0310-5

Dewey, H. M., Thrift, A. G., Mihalopoulos, C., Carter, R., Macdonell, R. A., McNeil, J. J., & Donnan, G. A. (2002). Informal care for stroke survivors: Results from the North East Melbourne Stroke Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Stroke, 33(4), 1028–1033. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.0000013067.24300.b0

Di Carlo, A. (2009). Human and economic burden of stroke. Age and Ageing, 38(1), 4–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afn282

Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135–168. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750

Dubois, B., Slachevsky, A., Litvan, I., & Pillon, B. (2000). The FAB: A frontal assessment battery at bedside. Neurology, 55(11), 1621–1626. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.55.11.1621

Dumont, C., St-Onge, M., Fougeyrollas, P., & Renaud, L.-A. (1998). Le fardeau perçu par les proches de personnes ayant des incapacités physiques. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65(5), 258–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841749806500503

Duncan, W. P., Wallace, M. D., Lai, J. S., Johnson, J. D., Embretson, J. S., & Laster, J. L. (1999). The Stroke Impact Scale Version 2.0: Evaluation of reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change. Stroke, 30(10), 2131–2140. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.30.10.2131

Dvorak, E. L., Gadson, D. S., Lacey, E. H., DeMarco, A. T., & Turkeltaub, P. E. (2021). Domains of health-related quality of life are associated with specific deficits and lesion locations in chronic aphasia. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair., 35(7), 634–643. https://doi.org/10.1177/15459683211017507

Flowers, H. L., Skoretz, S. A., Silver, F. L., Rochon, E., Fang, J., Flamand-Roze, C., & Martino, R. (2016). Poststroke aphasia frequency, recovery, and outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 97(12), 2188–2201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2016.03.006

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12(3), 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

Fonseca, J., Raposo, A., & Martins, I. P. (2019). Cognitive functioning in chronic post-stroke aphasia. Applied Neuropsychology Adult, 26(4), 355–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/23279095.2018.1429442

Stroke Foundation. (2021). Clinical Guidelines for Stroke Management. Retrieved from https://informme.org.au/en/Guidelines/Clinical-Guidelines-for-Stroke-Management

Fugl-Meyer, A. R., Bränholm, I.-B., & Fugl-Meyer, K. S. (1991). Happiness and domain-specific life satisfaction in adult northern Swedes. Clinical Rehabilitation, 5(1), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/026921559100500105

Fugl-Meyer, A. R., Melin, R., & Fugl-Meyer, K. S. (2002). Life satisfaction in 18- to 64-year-old Swedes: In relation to gender, age, partner and immigrant status. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 34(5), 239. https://doi.org/10.1080/165019702760279242

Geyh, S., Cieza, A., Kollerits, B., Grimby, G., & Stucki, G. (2007). Content comparison of health-related quality of life measures used in stroke based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF): A systematic review. Quality of Life Research, 16(5), 833–851. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-007-9174-8

Given, C. W., Given, B., Stommel, M., Collins, C., King, S., & Franklin, S. (1992). The caregiver reaction assessment (CRA) for caregivers to persons with chronic physical and mental impairments. Research in Nursing & Health, 15(4), 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770150406

Goh, H.-T., Tan, M.-P., Mazlan, M., Abdul-Latif, L., & Subramaniam, P. (2019). Social participation determines quality of life among urban-dwelling older adults with stroke in a developing country. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy, 42(4), E77–E84. https://doi.org/10.1519/JPT.0000000000000196

Golomb, B. A., Vickrey, B. G., & Hays, R. D. (2001). A review of health-related quality-of-life measures in stroke. PharmacoEconomics, 19(2), 155–185. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200119020-00004

Goodglass, H., Kaplan, E., & Barresi, B. (2000). Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination-Third Edition (BDAE-3). Lippincott.

Gorgoraptis, N., Zaw-Linn, J., Feeney, C., Tenorio-Jimenez, C., Niemi, M., Malik, A., Ham, T., Goldstone, A. P., & Sharp, D. J. (2019). Cognitive impairment and health-related quality of life following traumatic brain injury. NeuroRehabilitation, 44, 321–331. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-182618

Graessel, E., Berth, H., Lichte, T., & Grau, H. (2014). Subjective caregiver burden: Validity of the 10-item short version of the Burden Scale for Family Caregivers BSFC-s. BMC Geriatrics, 14(1), 23–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-14-23

Grant, J. S., Glandon, G. L., Elliott, T. R., Giger, J. N., & Weaver, M. (2004). Caregiving problems and feelings experienced by family caregivers of stroke survivors the first month after discharge. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 27(2), 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mrr.0000127639.47494.e3

Green, T. L., & King, K. M. (2010). Functional and psychosocial outcomes 1 year after mild stroke. Journal of Stroke & Cerebrovascular Diseases, 19(1), 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2009.02.005

Gronwall, D. (1977). Paced auditory serial-addition task: A measure of recovery from concussion. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 44, 367–373. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1977.44.2.367

Guyatt, G. H., Oxman, A. D., Kunz, R., Vist, G. E., Falck-Ytter, Y., & Schünemann, H. J. (2008). What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ, 336(7651), 995–998. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39490.551019.BE

Haley, W. E., Roth, D. L., Hovater, M., & Clay, O. J. (2015). Long-term impact of stroke on family caregiver well-being: A population-based case-control study. Neurology, 84(13), 1323–1329. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001418

Hall, K. S., Gao, S., Emsley, C. L., Ogunniyi, A. O., Morgan, O., & Hendrie, H. C. (2000). Community screening interview for dementia (CSI ‘D’); performance in five disparate study sites. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 15(6), 521–531. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1166(200006)15:6%3c521::AID-GPS182%3e3.0.CO;2-F

Hayden, J. A., Côté, P., & Bombardier, C. (2006). Evaluation of the quality of prognosis studies in systematic reviews. Annals of Internal Medicine, 144(6), 427–437. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-144-6-200603210-00010

Hayden, J. A., Tougas, M. E., Riley, R., Iles, R., & Pincus, T. (2014). Individual recovery expectations and prognosis of outcomes in non-specific low back pain: Prognostic factor exemplar review. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011284

Higgins, J. P. T., & Thompson, S. G. (2002). Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 21(11), 1539–1558. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1186

Higgins, J. P. T., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. British Medical Journal, 327(7414), 557–560. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

Hilari, K., Lamping, D. L., Smith, S. C., Northcott, S., Lamb, A., & Marshall, J. (2009). Psychometric properties of the Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life Scale (SAQOL-39) in a generic stroke population. Clinical Rehabilitation, 23(6), 544–557. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215508101729

Hilari, K., Needle, J. J., & Harrison, K. L. (2012). What are the important factors in health-related quality of life for people with aphasia? A systematic review. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 93(1), S86–S95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2011.05.028

Hochstenbach, J. B., Anderson, P. G., van Limbeek, J., & Mulder, T. T. (2001). Is there a relation between neuropsychologic variables and quality of life after stroke? Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 82(10), 1360–1366. https://doi.org/10.1053/apmr.2001.25970

Hogan, C., Cornwell, P., Fleming, J., Man, D. W. K., & Shum, D. H. K. (2023). Assessment of prospective memory after stroke utilizing virtual reality. Virtual Reality, 27(1), 333–346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-021-00576-5

Honan, C. A., McDonald, S., Tate, R., Ownsworth, T., Togher, L., Fleming, J., Anderson, V., Morgan, A., Catroppa, C., Douglas, J., Francis, H., Wearne, T., Sigmundsdottir, L., & Ponsford, J. (2019). Outcome instruments in moderate-to-severe adult traumatic brain injury: Recommendations for use in psychosocial research. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 29(6), 896–916. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2017.1339616

Hotter, B., Padberg, I., Liebenau, A., Knispel, P., Heel, S., Steube, D., Wissel, J., Wellwood, I., & Meisel, A. (2018). Identifying unmet needs in long-term stroke care using in-depth assessment and the Post-Stroke Checklist-The Managing Aftercare for Stroke (MAS-I) study. European Stroke Journal, 3(3), 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/2396987318771174

Howitt, S. C., Jones, M. P., Jusabani, A., Gray, W. K., Aris, E., Mugusi, F., Swai, M., & Walker, R. W. (2011). A cross-sectional study of quality of life in incident stroke survivors in rural northern Tanzania. Journal of Neurology, 258(8), 1422–1430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-011-5948-6

Hung, J. W., Huang, Y. C., Chen, J. H., Liao, L. N., Lin, C. J., Chuo, C. Y., & Chang, K. C. (2012). Factors associated with strain in informal caregivers of stroke patients. Chang Gung Medical Journal, 35(5), 392–401. https://doi.org/10.4103/2319-4170.105479

Hunt, S. M., McEwen, J., & McKenna, S. P. (1985). Measuring health status: A new tool for clinicians and epidemiologists. The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 35(273), 185–188.

Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org

Jackson, D., & Turner, R. (2017). Power analysis for random-effects meta-analysis. Research Synthesis Methods, 8(3), 290–302. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1240

Jaillard, A., Naegele, B., Trabucco-Miguel, S., LeBas, J. F., & Hommel, M. (2009). Hidden dysfunctioning in subacute stroke. Stroke, 40(7), 2473–2479. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.108.541144

Jokinen, H., Melkas, S., Ylikoski, R., Pohjasvaara, T., Kaste, M., Erkinjuntti, T., & Hietanen, M. (2015). Post-stroke cognitive impairment is common even after successful clinical recovery. European Journal of Neurology, 22(9), 1288–1294. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.12743

Jonkman, E. J., de Weerd, A. W., & Vrijens, N. L. H. (1998). Quality of life after a first ischemic stroke. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 98(3), 169–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0404.1998.tb07289.x

Kang, Y., & Na, D. L. (2004). Seoul verbal learning test. Human Brain Research & Consulting: Seoul, South Korea.

Kang, Y., Na, D. A., & Hanh, S. (1997). A validity study on the Korean mini-mental state examination (K-MMSE) in dementia patients. Journal of the Korean Neurological Association, 15(2), 300–308.

Kaplan, E., Goodglass, H., & Weintraub, S. (2001). Boston naming test (2nd Ed). Pro-ed: Austin TX USA.

Kertesz, A. (2006). Western Aphasia Battery-Revised (WAB-R): Examiner’s manual. Harcourt Assessment Incorporation: Philadelphia, PA USA.

Kessels, R. P. C. (2019). Improving precision in neuropsychological assessment: Bridging the gap between classic paper-and-pencil tests and paradigms from cognitive neuroscience. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 33(2), 357–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2018.1518489

Khalid, W., Rozi, S., Ali, T. S., Azam, I., Mullen, M. T., Illyas, S., Un-Nisa, Q., Soomro, N., & Kamal, A. K. (2016). Quality of life after stroke in Pakistan. BMC Neurology, 16(1), 250–250. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-016-0774-1

Kruithof, W. J., Post, M. W. M., van Mierlo, M. L., van den Bos, G. A. M., de Man-van Ginkel, J. M., & Visser-Meily, J. M. A. (2016). Caregiver burden and emotional problems in partners of stroke patients at two months and one year post-stroke: Determinants and prediction. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(10), 1632–1640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.04.007

Kruithof, W. J., Visser-Meily, J. M. A., & Post, M. W. M. (2012). Positive caregiving experiences are associated with life satisfaction in spouses of stroke survivors. Journal of Stroke & Cerebrovascular Diseases, 21(8), 801–807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2011.04.011

Kwa, V. I., Limburg, M., & de Haan, R. J. (1996). The role of cognitive impairment in the quality of life after ischaemic stroke. Journal of Neurology, 243(8), 599–604. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00900948

Kwok, T., Lo, R. S., Wong, E., Wai-Kwong, T., Mok, V., & Kai-Sing, W. (2006). Quality of life of stroke survivors: A 1-year follow-up study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 87(9), 1177–1182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2006.05.015

Larson, E. B., Kirschner, K., Bode, R. K., Heinemann, A. W., Clorfene, J., & Goodman, R. (2003). Brief cognitive assessment and prediction of functional outcome in stroke. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 9(4), 10–21. https://doi.org/10.1310/84yn-y640-8ueq-pdnv

Lawson, R. A., Yarnall, A. J., Duncan, G. W., Khoo, T. K., Breen, D. P., Barker, R. A., Collerton, D., Tayor, J.-P., & Burn, D. J. (2014). Severity of mild cognitive impairment in early Parkinson’s disease contributes to poorer quality of life. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 20(10), 1071–1075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.07.004

Lezak, M. D. (2012). Neuropsychological assessment (5th ed.). Oxford University Press: New York.

Lo, J. W., Crawford, J. D., Desmond, D. W., Bae, H. J., Lim, J. S., Godefroy, O., Roussel, M., Kang, Y., Jahng, S., Köhler, S., Staals, J., Verhey, F., Chen, C., Xu, X., Chong, E. J., Kandiah, N., Yatawara, C., Bordet, R., Dondaine, T., Mendyk, A. M., … Stroke and Cognition (STROKOG) Collaboration (2022). Long-term cognitive decline after stroke: An individual participant data meta-analysis. Stroke, 53(4), 1318–1327. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.035796

Lopez-Cancio, E., Jovin, T. G., Cobo, E., Cerda, N., Jimenez, M., Gomis, M., Hernandez-Perez, M., Caceres, C., Cardona, P., Lara, B., Renu, A., Llull, L., Boned, S., Muchada, M., & Davalos, A. (2017). Endovascular treatment improves cognition after stroke: A secondary analysis of REVASCAT trial. Neurology, 88(3), 245–251. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000003517

MacLeod, C. M. (1991). Half a century of research on the Stroop effect: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 109(2), 163–203. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.109.2.163

McDowd, J. M., Filion, D. L., Pohl, P. S., Richards, L. G., & Stiers, W. (2003). Attentional abilities and functional outcomes following stroke. The Journals of Gerontology Series b: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58(1), 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/58.1.P45

Mendis, S. (2013). Stroke disability and rehabilitation of stroke: World Health Organization perspective. International Journal of Stroke, 8(1), 3–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00969.x

Meyer, B., Ringel, F., Winter, Y., Spottke, A., Gharevi, N., Dams, J., Balzer-Geldsetzer, M., Mueller, I. K., Klockgether, T., Schramm, J., Urbach, H., & Dodel, R. (2010). Health-related quality of life in patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage. Cerebrovascular Diseases, 30(4), 423–431. https://doi.org/10.1159/000317078

Middleton, L. E., Lam, B., Fahmi, H., Black, S. E., McIlroy, W. E., Stuss, D. T., Danells, C., Ween, J., & Turner, G. R. (2014). Frequency of domain-specific cognitive impairment in sub-acute and chronic stroke. NeuroRehabilitation, 34(2), 305–312. https://doi.org/10.3233/nre-131030

Mitchell, A. J., Kemp, S., Benito-León, J., & Reuber, M. (2010). The influence of cognitive impairment on health-related quality of life in neurological disease. Acta Neuropsychiatrica, 22(1), 2–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1601-5215.2009.00439.x

Mole, J. A., & Demeyere, N. (2020). The relationship between early post-stroke cognition and longer term activities and participation: A systematic review. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 30(2), 346–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2018.1464934

Montgomery, R. J. V., Stull, D. E., & Borgatta, E. F. (1985). Measurement and the analysis of burden. Research on Aging, 7(1), 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027585007001007

Nasreddine, Z. S., Phillips, N. A., Bédirian, V., Charbonneau, S., Whitehead, V., Collin, I., Cummings, J. L., & Chertkow, H. (2005). The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53(4), 695–699. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

Nys, G. M., van Zandvoort, M. J., de Kort, P. L., van der Worp, H. B., Jansen, B. P., & Algra, A.,de Haan, E. H., & Kappelle, L. J. (2005). The prognostic value of domain-specific cognitive abilities in acute first-ever stroke. Neurology, 64(5), 821–827. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.WNL.0000152984.28420.5A

OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group. “The Oxford Levels of Evidence 2”. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653

Ones, K., Yilmaz, E., Cetinkaya, B., & Caglar, N. (2005). Quality of life for patients poststroke and the factors affecting it. Journal of Stroke & Cerebrovascular Diseases, 14(6), 261–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2005.07.003

Osterrieth, P. A. (1944). Le test de copie d’une figure complexe: Contribution à l’étude de la perception et de la mémoire. Archives De Psychologie, 30, 286–356.