Abstract

Chiari malformation has been classified as a group of posterior cranial fossa disorders characterized by hindbrain herniation. Chiari malformation type I (CM-I) is the most common subtype, ranging from asymptomatic patients to those with severe disorders. Research about clinical manifestations or medical treatments is still growing, but cognitive functioning has been less explored. The aim of this systematic review is to update the literature search about cognitive deficits in CM-I patients. A literature search was performed through the following electronic databases: MEDLINE, PsychINFO, Pubmed, Cochrane Library, Scopus, and Web of Science. The date last searched was February 1, 2023. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) include pediatric or adult participants with a CM-I diagnosis, (b) include cognitive or neuropsychological assessment with standardized tests, (c) be published in English or Spanish, and (d) be empirical studies. Articles that did not report empirical data, textbooks and conference abstracts were excluded. After the screening, twenty-eight articles were included in this systematic review. From those, twenty-one articles were focused on adult samples and seven included pediatric patients. There is a great heterogeneity in the recruited samples, followed methodology and administered neurocognitive protocols. Cognitive functioning appears to be affected in CM-I patients, at least some aspects of attention, executive functions, visuospatial abilities, episodic memory, or processing speed. However, these results require careful interpretation due to the methodological limitations of the studies. Although it is difficult to draw a clear profile of cognitive deficits related to CM-I, the literature suggests that cognitive dysfunction may be a symptom of CM-I. This suggest that clinicians should include cognitive assessment in their diagnostic procedures used for CM-I. In summary, further research is needed to determine a well-defined cognitive profile related to CM-I, favoring a multidisciplinary approach of this disorder.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chiari malformations (CM) are a group of posterior cranial fossa disorders characterized by hindbrain herniation (Manto & Christian, 2013; Tubbs et al., 2020). From the first description of the different subtypes by Hans von Chiari at the end of nineteenth century, the current classification includes six main typologies (0, I, 1.5, II, III, and IV) based upon their pathophysiology and clinical presentation, in addition to two more recently proposed categories (3.5 and V) (Massimi et al., 2011; Rindler & Chern, 2020; Tubbs & Turgut, 2020) (see Table 1 for a more detailed description). Accurate data on the prevalence of each CM typology are not available, but it is known that Chiari malformation type I (CM-I) is the most frequent, with estimated rates around 1/1000–5000 cases (Urbizu et al., 2013), although a higher prevalence has been reported in retrospective magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies with general population (Öktem et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2013; Vernooij et al., 2007).

CM-I is characterized by a displacement of cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum (> 3–5 mm below McRae line) (Lawrence et al., 2018), which leads to a significant craniocervical junction compression (Meadows et al., 2001; Smith et al., 2013) (see Fig. 1). The diagnosis typically takes place at around 30–40 years old (Avellaneda et al., 2009), but there are also pediatric patients (Massimi et al., 2021). About its etiology, theories suggesting osseus dysplasia are widely accepted (Marin-Padilla & Marin-Padilla, 1981; Meadows et al., 2001), which are also supported by genetic findings (Capra et al., 2019; Markunas et al., 2020; Urbizu et al., 2017). Also, a loss of compliance of the spinal canal in the cervical spine area has been proposed as a cause of CM-I symptoms (García et al., 2022; Labuda et al., 2022).

The heterogeneity among CM-I patients ranges from asymptomatic cases to those with serious medical complications. The most frequent complaints include headaches and cervical pain, in addition to a set of symptoms attributed to craniocervical compression and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow disturbances (i.e., limb weakness, sensory and motor changes) (Avellaneda et al., 2009; Novegno, 2019). Literature about CM-I outcomes has also reported high diversity among patients. Symptomatic patients show a positive trend after surgery, with less percentage of worsening, and those who are asymptomatic present a greater stability of their clinical manifestations and amigdalar ectopia (Arnautovic et al., 2015; Chatrath et al., 2019; Langridge et al., 2017). Despite the progress, the understanding of the natural history of CM-I requires further research of longer clinical and imaging follow-up (Maher, 2020). Usually, the most administered treatment for CM-I patients consists of posterior fossa decompression (PFD) surgery, which has shown favorable results (Mueller & Oro’, 2005; Parker et al., 2013), mainly combined with other techniques such as duraplasty (Chai et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2017; Kumar et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2016).

While research about clinical manifestations, surgical outcomes, or improvements in medical treatments is still growing, cognitive functioning in CM-I patients has been less explored. Nevertheless, recent studies also highlight the importance of considering the cognitive disturbances in the clinical profile of CM-I patients (Allen et al., 2014; Fischbein et al., 2015; Rogers et al., 2018). Both physical and cognitive deficits affect negatively CM-I patients’ quality of life (Bakim et al., 2013; Meeker et al., 2015), reporting high rates of anxious-depressive symptomatology (Fischbein et al., 2015; Garcia et al., 2019; Mestres et al., 2012). It is therefore meaningful a more comprehensive approach in this pathology, considering physical, psychological, and cognitive status of patients.

At the end of twentieth century, the conceptualization of the cerebellum changed, associating cognitive and affective processes to this structure in addition to the classically associated motor functions (Leiner et al., 1986, 1993; Schmahmann, 2019). Schmahmann and Sherman (1998) proposed the “cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome” (CCAS) to define a set of cognitive disturbances that includes four main areas: executive functioning, spatial cognition, language, and personality. The CCAS has been reported across different cerebellar disorders (Argyropoulos et al., 2020), and it can be assessed through a specific scale (Hoche et al., 2018). Moreover, neuroimaging studies have suggested strong evidence about anatomical and functional connectivity between cerebellum and cortical areas (Buckner et al., 2011; Guell & Schmahmann, 2020; Houston et al., 2021; Stoodley et al., 2012). Particularly, the posterior lobe of cerebellum has been directly related to cognitive functions, while anterior lobe has a main role in motor tasks (Stoodley et al., 2016). Recent research suggests that fiber connection disruptions could affect cognitive performance controlled by certain cortical regions (Habas et al., 2009; Schmahmann, et al., 2019; Stoodley et al., 2012). Houston et al. (2021) showed that intrinsic functional connectivity in CM-I using resting-state fMRI methods showed hypo-connectivity relative to healthy controls for cognitive associations, but hyper-connectivity when associated with pain (i.e., CM-I patients showed hyper-connectivity with cortical areas associated with pain relative to healthy controls).

Rogers et al. (2018) published a systematic review of cognition in CM-I, showing that CM-I patients may experience cognitive dysfunctions, in addition to clinical symptomatology. Likewise, this article shows the paucity of scientific research focused on the cognitive impact of CM-I. Since that publication, new articles have been published that extend our understanding of cognitive dysfunction associated with this disorder. Also, Houston et al. (2022) showed the importance of considering pain effects when considering cognitive effects in CM-I. For example, distraction due to pain can result in cognitive dysfunction in CM-I (e.g., Allen et al., 2018), so it is important to consider whether there are cognitive effects in CM-I that are separate from the distracting effect of pain. The aim of this present study is to conduct a systematic review to update that of Rogers et al. (2018) and Houston et al. (2022), considering adult and pediatric populations, and to point out the significant developments and remaining challenges.

Method

This study has been conducted considering the PICOS criteria (see Table 2) and following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) methodology.

Search Strategy

A systematic review was carried out to identify original empirical studies that assessed cognitive functioning in CM-I patients. We queried the following online databases: MEDLINE, PsychINFO, Pubmed, Cochrane Library, Scopus, and Web of Science. We used a combination of the following keywords: “Chiari malformation” and “cognitive,” “neuropsychological,” “cognitive assessment,” “neuropsychological assessment,” “cognition,” and “neuropsychology.”

The literature search was conducted until February 1, 2023.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be included in the review, studies had to (a) include pediatric or adult participants with a CM-I diagnosis, (b) include cognitive or neuropsychological assessment with standardized tests (one or more determinants of cognitive performance), (c) be published in English or Spanish in a scientific journal, and (d) be empirical studies. For the purposes of this study, both with and without decompressive surgery patients were considered. Patients with comorbid diagnoses were also included if those were related to CM-I disorder (e.g., syringomyelia).

Articles that did not report empirical data were excluded from the review (i.e., review articles, meta-analyses, descriptive observations, expert commentaries). Data from textbooks and conference abstracts were also excluded.

Data Extraction

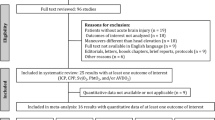

The update search yielded 918 studies (M.G.). After eliminating duplicates, 243 were screened by two independent authors (M.G. and M.P.) analyzing the titles and abstracts. After the screening, those potentially suitable (n = 32) were fully examined (M.G. and I.A.). A final consensus regarding the eligibility of each article was reached by discussion between both reviewers (M.G. and I.A.). Finally, 23 articles were obtained. First round for data extraction was conducted by one researcher (M.G.) and later, other reviewer (M.P.) assessed the accuracy of the extracted data. Studies that met the established criteria were summarized according to (i) authors, (ii) sample size, (iii) sample characteristics (age and gender), (iv) surgical treatment, (v) clinical signs and symptoms, (vi) neuropsychological tests, (vii) cognitive deficits, and (viii) cerebral imaging data of interest. The reference lists of selected articles were reviewed for possible additional publications and five studies were also obtained by manual searches, resulting in 28 articles included in this systematic review. The flow diagram of identification of relevant studies is shown in Fig. 2.

Risk of Bias

Risk of bias was evaluated for each included study using the adapted version of the modified Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (Bawor et al., 2014). This scale was used following the background of the previous systematic review about cognition in CM-I (Rogers et al., 2018). It allows to examine quality of evidence of each publication considering different domains: participants selection (selection bias), control confounding (performance bias), statistical methods (detection bias) and outcome measures (information bias). Each item ranges from 0 (high risk) to 3 (low risk). No studies were excluded on the basis of risk of bias.

Results

General Overview

Of the initial 918 considered articles, 28 studies met the eligibility criteria for inclusion in this systematic review. Selected articles with adult patients are shown in Table 3 (n = 21), and articles with pediatric samples are listed in Table 4 (n = 7). From a global view, only two studies reported no deficits in CM-I patients (Almotairi et al., 2020; Klein et al., 2014), whereas the remaining 26 studies reported at least one cognitive domain decreased in CM-I patients. Moreover, the vast majority of selected articles included a sample size below 30 CM-I participants, although five articles exceeded samples sizes of 30 CM-I participants (Allen et al., 2018; García et al., 2018b; Lacy et al., 2016; Lázaro et al., 2018). As regards the latter issue, smaller sample sizes are one of the main limitations of the cognitive studies conducted in CM-I patients (although these studies typically include both CM-I and healthy control samples). It should also be noted that there exists considerable heterogeneity in the methods used in these studies as well as the diversity of cognitive tests and protocols, ranging from screening tasks such as Minimental State Examination (MMSE) (Pearce et al., 2006) to comprehensive batteries such as Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) or Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WIPPSI) (e.g., García et al., 2018a; Klein et al., 2014; Novegno et al., 2008). Thus, the comparison across different researches is limited, and it is difficult to draw a clear conclusion from them.

Risk of bias and overall quality of evidence analyses showed that sample-related methods need to be improved in further research. The main remaining challenges are focused on larger sample sizes and longitudinal studies (Table 5).

Characterization and Cognitive Functioning in Adult Patients

Considering the articles with adult samples, 21 studies met the established criteria. The patient’s age ranged from 15 to 64 years old, and the number of female participants was significantly higher in all group studies. Clinical presentation of CM-I patients was also heterogeneous, ranging from common symptoms such as headache to more severe syndromes such as syringomyelia, which has been referred to in ten studies (Almotairi et al., 2020; García et al., 2018a, b, 2020a, b; Houston et al., 2019; Houston et al., 2020; Houston et al., 2021; Lázaro et al., 2018; Seaman et al., 2021) or hydrocephalus, which has been reported in five articles (García et al., 2018a, 2020a, b, Lázaro et al., 2018; Pearce et al., 2006) (for more details about signs and symptoms, see Table 3).

Of the total of 21 studies, four were case reports (Del Casale et al., 2012; Klein et al., 2014; Mahgoub et al., 2012; Pearce et al., 2006), being three single-case designs (Del Casale et al., 2012; Mahgoub et al., 2012; Pearce et al., 2006). As can be seen in Table 3, only four articles exceeded 30 patients (Allen et al., 2018; García et al., 2018a, b; Lázaro et al., 2018), which points out the lack of large cohort studies as one of the most significant limitation of the literature about cognition in CM-I.

Analyzing the sample design, 15 of a total of 21 articles included a control group (Allen et al., 2014; Allen et al., 2018; Besteiro & Torres, 2018; García et al., 2018a, b, 2020a, b; Houston et al., 2018; Houston et al., 2019; Houston et al., 2020; Houston et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2011; Lacy et al., 2019; Lázaro et al., 2018; Yilmaz et al., 2022); however, only nine were age-, gender-, and education-matched (García et al., 2018a, b, 2020a, b; Houston et al., 2018; Houston et al., 2019; Houston et al., 2020; Lázaro et al., 2018; Yilmaz et al., 2022). That is another limitation of research examining cognitive functioning in the CM-I population.

There is also considerable diversity in surgical treatment across the studies. Seven of them included CM-I patients without any surgical intervention (Besteiro & Torres, 2018; Del Casale et al., 2012; García et al., 2018b; Houston et al., 2019; Klein et al., 2014; Lacy et al., 2019; Yilmaz et al., 2022), whereas four completed their total samples with undergoing surgery patients (Allen et al., 2014; Almotairi et al., 2020; Pearce et al., 2006; Seaman et al., 2021). Eight contained mixed samples combining patients with and without surgical treatments (Allen et al., 2018; García et al., 2018a, 2020a, b; Houston et al., 2018; Houston et al., 2020; Houston et al., 2021; Lázaro et al., 2018). Two studies did not specify this information (Kumar et al., 2011; Mahgoub et al., 2012). All of the surgical treatments consisted in PFD procedures, except for Pearce et al. (2006) case report, who underwent a ventriculoperitoneal shunt blockade (VSB).

After our literature search, Almotairi et al. (2020) and Seaman et al. (2021) were the only two identified studies that analyzed cognitive functioning in CM-I patients comparing pre- and post-surgical status. In the Almotairi et al.’s (2020) study, 11 patients (two missed from the original sample) were administered neuropsychological assessment both before and after PFD procedure. Before the surgery, they found no significant deficits in cognitive performance but they reported a significant improvement after PFD in the following functions: verbal learning, psychomotor and verbal speed, and inhibitory control. In contrast, Seaman et al. (2021) evaluated 19 CM-I (7 missed from the original sample) through a large battery of neuropsychological tests both before and after PFD, suggesting that CM-I patients had a decreased performance on visuospatial abilities, visual memory, and psychomotor abilities. In addition, contrary to what Amotairi et al.’s (2020) report, no differences were found when comparing results between pre- and post-surgical status (Seaman et al., 2021).

With regard to the adult CM-I patients’ performance across the different cognitive domains, the review suggested a generalized cognitive deficit related to this pathology, apart from physical manifestations such as chronic pain or muscle weakness. A worse performance by CM-I patients has been reported in attention (Allen et al., 2018; Besteiro & Torres, 2018; Houston et al., 2018; Houston et al., 2019; Houston et al., 2020; Houston et al., 2021; Pearce et al., 2006; Mahgoub et al., 2012), orientation (Mahgoub et al., 2012; Pearce et al., 2006), executive functioning (Allen et al., 2014; Besteiro & Torres, 2018; García et al., 2018a, b; Kumar et al., 2011; Mahgoub et al., 2012; Yilmaz et al., 2022), visual (Del Casale et al., 2012; Seaman et al., 2021) and verbal memory (Allen et al., 2018; García et al., 2018a, b; Houston et al., 2019; Lacy et al., 2019; Mahgoub et al., 2012), visuospatial abilities (García et al., 2018a, b, 2020b; Kumar et al., 2011; Lacy et al., 2019; Seaman et al., 2021), processing speed (Allen et al., 2014; Del Casale et al., 2012; García et al., 2018a, b; Houston et al., 2018; Houston et al., 2020; Kumar et al., 2011; Seaman et al., 2021; Yilmaz et al., 2022), verbal fluency (Del Casale et al., 2012; García et al., 2018a, b; Lacy et al., 2019; Lázaro et al., 2018), naming (García et al., 2018a, b), emotional facial recognition (García et al., 2018a; Houston et al., 2018), and social cognition (García et al., 2018a, b, 2020a). Moreover, there are four studies that suggest CM-I patients present a generalized cognitive deficit (Houston et al., 2019; Lacy et al., 2019; Mahgoub et al., 2012; Yilmaz et al., 2022). Nevertheless, as it has been mentioned above, two studies concluded no deficits were present in CM-I patients (Almotairi et al., 2020; Klein et al., 2014).

Seven articles reported a decreased cognitive performance even after controlling for the effects of chronic pain and anxious-depressive symptomatology (Allen et al., 2014; García et al., 2018a, b, 2020a, b; Houston et al., 2019; Houston et al., 2021). In addition, no differences were found between decompressed and non-decompressed CM-I patients in cognitive performance (Allen et al., 2018; García et al., 2018a).

In sum, cognitive functioning appears to be affected in adult CM-I patients, at least some aspects of attention, executive functions, visuospatial abilities, episodic memory, and processing speed, which are the most supported by the literature results. Moreover, this impairment does not seem to be necessarily related to chronic pain or psychiatric symptoms, but there is as yet no clear conclusion regarding the effect of decompressive surgery on cognitive performance.

Characterization and Cognitive Functioning in Pediatric Patients

The onset age of CM-I is typically around the third decade (e.g., Smith et al., 2013), but it can also be diagnosed in pediatric population, sometimes leading to complex clinical manifestations. In this systematic review, seven studies met the eligibility criteria for the inclusion (Table 4). Patients’ ages ranged from 1 to 18 years old. Regarding gender data, except for Lacy et al.’s (2016) study (41 male vs. 36 female), the number of female participants was superior. Considering signs and symptoms, it was found a high heterogeneity, from asymptomatic patients (Sari & Ozum, 2021) to individuals with common symptomatology related to CM-I such as headache and neck pain (Novegno et al., 2008) or more severe cases with hydrocephalus or syringomyelia (Lacy et al., 2016). Three studies referred to developmental anomalies affecting intellectual abilities (Gabrielli et al., 1998; Grosso et al., 2001; Haapanen, 2007).

Regarding sample size of each study, two studies were case reports (Haapanen, 2007; Riva et al., 2011), of which Riva et al.’s (2011) report was a single-case study. Except for Lacy et al.’s (2016) article, the remaining studies had 10 or less participants. Likewise, only Sari and Ozum (2021) study had an age- and gender-matched control group. In view of these data, methodological limitations are considerable for research examining pediatric subjects with CM-I.

Concerning the effect of surgical treatment, two studies included decompressed subjects in their sample (Lacy et al., 2016; Riva et al., 2011), one included non-operated patients (Sari & Ozum, 2021), and four of them did not specify this information (Gabrielli et al., 1998; Grosso et al., 2001; Haapanen, 2007; Novegno et al., 2008). However, only Riva et al. (2011) analyzed cognitive functioning both before and after surgery. In this study, two case reports were included. The first case was a 5-year-old boy, who was evaluated and showed an improved performance on language abilities but a progressive deterioration of attention after decompressive neurosurgery. The second case was a 15-year-old girl who showed the inverse performance, a worsening in language but an improvement in attention (Riva et al., 2011).

Of the total of seven studies, a generalized cognitive deficit was reported in four of them (Gabrielli et al., 1998; Grosso et al., 2001; Haapanen, 2007; Sari & Ozum., 2021). However, analyzing specific cognitive domains, pediatric CM-I patients showed a decreased performance in the following areas: attention (Novegno et al., 2008; Riva et al., 2011), executive functioning (Lacy et al., 2016; Riva et al., 2011), visual (Novegno et al., 2008) and verbal memory (Haapanen, 2007), processing speed (Haapanen, 2007; Novegno et al., 2008), verbal fluency (Novegno et al., 2008), language (Riva et al., 2011), and metacognition (Lacy et al., 2016). The identified deficits in the Lacy et al.’s (2016) study were collected by parent reports using the Brief Rating Inventory of Executive Functioning (BRIEF). According to their results, CM-I patients had a worse executive functioning regardless their gender, age, or surgical status.

Overall, there is scarce literature about cognitive consequences in pediatric CM-I patients and comparing to adult studies, methodological barriers are more severe. However, there is sufficient evidence to consider cognitive aspects in children with CM-I, especially to prevent delayed acquisition and development of cognitive skills.

Neuroimaging Data

Analyzing neuroimaging evidence, five studies with adult samples accompanied their neuropsychological findings with brain structure and functional data (Houston et al., 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021; Kumar et al., 2011;). Six studies in adult CM-I patients (Allen et al., 2014; Allen et al., 2018; Besteiro & Torres, 2018; Del Casale et al., 2012; Klein et al., 2014; Mahgoub et al., 2012) and four in pediatric patients (Gabrielli et al., 1998; Grosso et al., 2001; Haapanen, 2007; Novegno et al., 2008) reported information from MRI scans. However, they just indicated Chiari-related anatomical signs such as cerebellar ectopia below the foramen magnum and posterior fossa volumetric anomalies. Lastly, the remaining ten studies with adult patients (Almotairi et al., 2020; García et al., 2018a, b, 2020a, b; Lacy et al., 2019; Lázaro et al., 2018; Pearce et al., 2006; Seaman et al., 2021; Yilmaz et al., 2022) and three with pediatric subjects (Lacy et al., 2016; Riva et al., 2011; Sari & Ozum, 2021) did not include neuroimaging tests in their reports.

To our knowledge, Kumar et al. (2011) were the first study to include neuroimaging tests and their correlation with cognitive performance in CM-I. These authors acquired Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) data from ten CM-I patients and ten healthy controls. When comparing both groups, they found microstructural anomalies in different brain regions. Specifically, they reported the following findings: (a) decreased fractional anisotropy (FA) and increased mean diffusivity (MD) in putamen, genu, splenium, and fornix; (b) increased MD in cingulum; (c) increased axial diffusivity (AD) in putamen, thalamus, and fornix; and (d) increased radial diffusivity (RD) in fornix and cingulum. Moreover, they found some correlations between DTI metrics and cognitive measures such as attention, executive functioning, visuoperceptual abilities, and processing speed. Based on these findings, they suggested a possible deficit in myelination in CM-I patients, leading to an abnormal development of the white matter (Kumar et al., 2011). Following with DTI findings, Houston et al. (2020) reported noteworthy findings according to different parameters: (a) increased FA in the internal capsule, corpus callosum, stratum, longitudinal fasciculus, middle cerebellar peduncle, and corona radiata; (b) decreased RD in the left anterior corona radiata; and (c) decreased MD in the corpus callosum and left superior longitudinal fasciculus. Their study compared 18 CM-I patients and 18 healthy controls; however, when self-reported pain was controlled for, differences between groups in FA, RD, and MD were eliminated.

Houston et al. (2019) correlated brain and cerebellar volumetric measures from MRI scans with cognitive scores obtained through the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS). They assessed 18 CM-I subjects and 18 healthy controls and found that a greater tonsillar descent correlated with worse delayed memory and a greater osseous area correlated with better attention. Apart from cerebellar tonsils herniation below the foramen magnum, they reported posterior fossa volumetric anomalies and shorter intracranial heights in CM-I patients. In a later study, Houston et al. (2021) analyzed the cortico-cerebellar connectivity through a resting-state fMRI technique and reported the following significant abnormalities: (a) hyperconnectivity between the posterior cingulate cortex and the left globus pallidus, and between the cerebellar lobule VIII and the left postcentral gyrus and vermis IX and the precuneus and (b) hypoconnectivity between posterior cerebellar pathway and the right supramarginal gyrus.

Finally, Houston et al. (2018) recorded the neural activity of 19 CM-I patients compared to 19 healthy controls using electroencephalography (EEG). They found neurophysiological activity anomalies consistent with a dysfunctional fronto-parietal attentional network. Although specific data from EEG recording have not been included in more studies of this systematic review, Grosso et al. (2001) and Haapanen (2007) also reported EEG abnormalities in CM-I subjects.

As literature shows, the neuroimaging studies produce useful volumetric and functional information which has suggested the correlation with cognitive measures (see Fig. 3 for an illustrative summary). Nevertheless, and in spite of the latest advances, there is not yet enough evidence to use those parameters as optimal predictors of surgical outcomes, nor as helpful measures to have a deep knowledge about neural mechanisms underlying CM-I disorder.

Discussion

The initial aim of this systematic review was to update the knowledge of cognitive functioning in CM-I patients. The existing literature has been divided between adult (Table 3) and pediatric studies (Table 4). On the whole, except for two studies (Almotairi et al., 2020; Klein et al., 2014), the remaining works reported at least one cognitive domain decreased in CM-I patients. Although the identified studies were not equally distributed between adult and pediatric samples, both populations have shown cognitive impairments, and it seems to be a partial consensus about the most affected domains, which include attention, executive functioning, visuospatial abilities, episodic memory, and processing speed. However, due to the potential biases and methodological limitations found, it is difficult to draw a common profile of deficits related to CM-I disorder.

Based on the studies we reviewed, we find that there is a notable lack of unanimity in neuropsychological protocols. From large cognitive test batteries to specific tasks, a broad spectrum of cognitive domains has been assessed; however, not all studies included a comprehensive assessment of CM-I patients. This prevents drawing conclusions about certain domains such as social cognition, which has been little studied, or language, remaining less explored in adult population. Moreover, some variables such as chronic pain or anxious-depressive symptomatology have not been controlled for in all studies. Chiari-related pain and psychological symptoms are potential cofounding variables, and the associations between them and cognitive performance should be considered in further research. As we have mentioned before, the vast majority of sample sizes are low and without longitudinal measures; therefore, the interpretation of results and conclusions regarding cognitive functioning of CM-I patients must be done with caution. Moreover, this issue is particularly relevant in pediatric samples with related conditions. In this line, further studies should consider the inclusion of homogeneous matching control groups. Comparing this systematic review with the previous work of Rogers et al. (2018), we can take an optimistic view due to the growing interest in the research about cognitive aspects of CM-I disorder. Since the most recent article included in the Rogers et al.’s (2018) literature review, 15 more works with adult samples have been published and one more with pediatric population. Likewise, some of previous methodological limitations such as small sample size or the inclusion of neuroimaging techniques have been tried to overcome. However, it is still insufficient to obtain a clear cognitive profile related to CM-I disorder.

Considering the most affected cognitive domains that have been indicated in the literature reviewed (attention, executive functioning, visuospatial abilities, memory, and processing speed), there seems to be agreement with the Schmahmann and Sherman’s (1998) syndrome. The CCAS involves executive, visuospatial, and linguistic deficits, which is partly supported by literature when CM-I patients are evaluated. Actually, CM-I disorder has been included as one of the congenital conditions that lead to CCAS (Kraan, 2017). The most supported hypothesis that could explain the cognitive deficits in CM-I patients suggest a dysfunction in cortico-cerebellar circuitry, resulting from structure compression and developmental mechanisms (Steinberg et al., 2020). Neuroimaging studies have identified neural pathways between cerebellum and cortical areas, including motor, parietal, prefrontal, temporal, oculomotor, basal ganglia, and limbic loops (Buckner et al., 2011; D’Angelo & Casali, 2013), which could lead to planning, visual-motor coordination, procedural learning, visuospatial organization, or emotion-related deficits. Habas et al. (2009) studied the involvement of the cerebellum in non-motor functions, suggesting four main connectivity networks: sensorimotor, default mode, executive, and salience network. Similarly, Houston et al. (2021) found group differences in the default mode network activation in CM-I patients compared to controls. To explain the cerebellar role in cognition, the dysmetria of thought theory has been proposed (Guell et al., 2015), which occurs due to a disruption of the cognitive cortico-cerebellar pathways, leading to the CCAS (Schmahmann, 2019). Additionally, the topographic representation of the CCAS has been located in the cerebellar posterior lobe (specifically in VI, VII, and IX hemispheric areas), whereas anterior lobe has motor representation (Schmahmann, 2019). Functional topography studies support the anterior–posterior distinction to locate motor vs. cognitive outcomes (dysmetria of movement vs. dysmetria of thought) following cerebellar lesions (Stoodley et al., 2016). Despite the lack of comprehensive functional neuroimaging studies with CM-I patients and considering the anatomical anomalies in CM-I disorder, it is not unreasonable to think that cognitive deficits were caused by damage to cortico-cerebellar connections.

Research has identified microstructural anomalies in CM-I patients affecting white matter (Abeshaus et al., 2012; Houston et al., 2020; Kumar et al., 2011), and grey matter integrity (Akar et al., 2017; Aydin & Ozoner, 2019). Likewise, both Krishna et al. (2016) and Kurtcan et al. (2018) suggested microstructural alterations in the brainstem region. Volumetric anomalies have also been identified comparing CM-I patients and controls (Biswas et al., 2019). In this systematic review, five studies reported neuroimaging findings, but only three of them found significant correlations between cognitive performance and volumetric (Houston et al., 2019), and functional measures (Houston et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2011). Regarding the correlation between the magnitude of tonsillar ectopia and cognitive performance, Houston et al. (2019), Grosso et al. (2001) and Novegno et al. (2008) reported a significant finding between those parameters, whereas previous research did not find this association (Crittenden et al., 2017; García et al., 2018b; Stephenson et al., 2017). Moreover, García et al. (2020a) found no correlation between tonsillar ectopia and perceived physical pain reported by CM-I patients. The accumulated evidence about the tissue damaged and volumetric anomalies in CM-I patients may underlie the cognitive dysfunctions reported across the studies. However, this assumption will not be sufficiently validated until an exhaustive study is conducted, including a comprehensive cognitive protocol, longitudinal measures and neuroimaging tests.

A self-report from the CCRC (Conquer Chiari Research Center) revealed that 43.9% of 768 CM-I patients indicated memory problems, 43.8% reported aphasia, 31.6% had problems with decision-making and 29.2% had planning problems (Fischbein et al., 2015). Apart from cognitive complaints, psychological disorders are commonly related to CM-I disorder, such as depression and anxiety, representing in the Fischbein et al.’s (2015) study a percentage of 31.8% and 25.4%, respectively. Higher percentages have been reported in the Garcia et al. (2019) research, in which of the total of 1034 CM-I patients, 44% reported moderate-severe levels of depression, and of the total of 1010 patients, 60% indicated moderate-severe levels of anxiety. These high scores, as well as that reported in this systematic review, reflect that we should not underestimate neurocognitive and psychological symptoms in the clinical presentation of CM-I disorder.

Before the conclusion, it is important to underline the limitations of the studies here reviewed. Although we have set up closed selection criteria to include studies, the vast majority recruited small sample sizes of CM-I patients or presented single-case reports. Likewise, less than half of the studies included a comparative control group, and even less were age-, gender-, and education-matched. Both limitations are more evident in pediatric population. These issues should be addressed in further research, studies with larger sample sizes and more rigorous designs thoroughly considered case–control differences are needed for the Chiari literature body. Moreover, studies administered different neurocognitive measures, and sometimes without controlling for pain and anxious-depressive symptomatology. These factors could limit the comparison of their results and conclusions of cognitive profile in CM-I patients. Chiari-related pain and psychological symptoms are commonly associated with neuroanatomical parameters or specific cognitive deficits; therefore, future studies should consider that relationship. In addition, some patients were also diagnosed with hydrocephalus, making the attribution of cognitive deficits to the CM-I less clear. There are few rigorous studies that compare the effect of decompressive surgery on cognitive performance but these had conflicting conclusions. In addition, few studies included neuroimaging techniques that support cognitive findings analyzing the underlying neural mechanisms. Lastly, there are no longitudinal studies that allow us to know the course of cognitive deficits in CM-I disorder.

Conclusion

The literature here reviewed seems to yield a partial consensus about the cognitive deficits present in CM-I. Patients mainly showed a lower performance in attention, executive functioning, visuospatial abilities, episodic memory, and processing speed. However, these results require careful interpretation due to the aforementioned methodological limitations of the studies. In addition, although the research of cognitive profile of CM-I has gained increasing attention, the effect of neurosurgery and psychological symptomatology on cognitive performance remains little explored. The quality of life of CM-I patients could be decreased due to the impact of these symptoms on their daily lives, thus, clinicians should include the cognitive assessment in their diagnostic procedures. Researchers should focus on longitudinal designs with larger sample sizes and comprehensive neuropsychological protocols, including neuroimaging data, which is an urgent challenge. In summary, further research is needed to determine a well-defined cognitive profile related to CM-I, favoring a multidisciplinary approach of this disorder.

Availability of Data and Materials

Not applicable.

References

Abeshaus, S., Friedman, S., Poliachik, S., Poliakov, A., Shaw, D., Ojemann, J. G., & Ellenbogen, R. G. (2012, October 6–10). Diffusion tensor imaging changes with decompression of Chiari I malformation [poster]. Annual Meeting Congress of Neurological Surgeons, Chicago, USA. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.neu.0000417804.07223.5d

Akar, E., Kara, S., Akdemir, H., & Kırış, A. (2017). 3D structural complexity analysis of cerebellum in Chiari malformation type I. Medical and Biological Engineering and Computing, 55(12), 2169–2182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-017-1661-7

Allen, P. A., Delahanty, D., Kaut, K. P., Li, X., Garcia, M., Houston, J. R., Tokar, D. M., Loth, F., Maleki, J., Vorster, S., & Luciano, M. G. (2018). Chiari 1000 registry project: Assessment of surgical outcome on self-focused attention, pain, and delayed recall. Psychological Medicine, 48(10), 1634–1643. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717003117

Allen, P. A., Houston, J. R., Pollock, J. W., Buzzelli, C., Li, X., Harrington, A. K., Martin, B. A., Loth, F., Lien, M. C., Maleki, J., & Luciano, M. G. (2014). Task-specific and general cognitive effects in Chiari malformation type I. PLoS ONE, 9(4), e94844. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0094844

Almotairi, F. S., Hellström, P., Skoglund, T., Nilsson, Å. L., & Tisell, M. (2020). Chiari I malformation—neuropsychological functions and quality of life. Acta Neurochirurgica, 162(7), 1575–1582. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-019-03897-2

Argyropoulos, G. P. D., van Dun, K., Adamaszek, M., Leggio, M., Manto, M., Masciullo, M., Molinari, M., Stoodley, C. J., Van Overwalle, F., Ivry, R. B., & Schmahmann, J. D. (2020). The cerebellar cognitive affective/Schmahmann syndrome: A task force paper. Cerebellum, 19(1), 102–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-019-01068-8

Arnautovic, A., Splavski, B., Boop, F. A., & Arnautovic, K. I. (2015). Pediatric and adult Chiari malformation type I surgical series 1965–2013: A review of demographics, operative treatment, and outcomes. Journal of Neurosurgery. Pediatrics, 15(2), 161–177. https://doi.org/10.3171/2014.10.peds14295

Avellaneda, A., Isla, A., Izquierdo, M., Amado, M. E., Barrón, J., Chesa i Octavio, E., De la Cruz, J., Escribano, M., Fernández de Gamboa, M., García-Ramos, R., García, M., Gómez, C., Insausti, J., Navarro, R., & Ramón, J. R. (2009). Malformations of the craniocervical junction (Chiari type I and syringomyelia: classification, diagnosis and treatment). BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 10(Suppl 1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-10-S1-S1

Aydin, S., & Ozoner, B. (2019). Comparative volumetric analysis of the brain and cerebrospinal fluid in Chiari type I malformation patients: A morphological study. Brain Sciences, 9(10), 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci9100260

Bakim, B., Goksan Yavuz, B., Yilmaz, A., Karamustafalioglu, O., Akbiyik, M., Yayla, S., Yuce, I., Alpak, G., & Tankaya, O. (2013). The quality of life and psychiatric morbidity in patients operated for Arnold-Chiari malformation type I. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 17(4), 259–263. https://doi.org/10.3109/13651501.2013.778295

Bawor, M., Dennis, B. B., Anglin, R., Steiner, M., Thabane, L., & Samaan, Z. (2014). Sex differences in outcomes ofmethadone maintenance treatment for opioid addiction: A systematic review protocol. Systematic Reviews, 3, 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-3-45

Besteiro, J. L., & Torres, J. M. (2018). Anomalies in the cognitive-executive functions in patients with Chiari malformation type I. Psicothema, 30(3), 316–321. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2017.401

Biswas, D., Eppelheimer, M. S., Houston, J. R., Ibrahimy, A., Bapuraj, J. R., Labuda, R., Allen, P. A., Frim, D., & Loth, F. (2019). Quantification of cerebellar crowding in type I Chiari malformation. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 47(3), 731–743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-018-02175-z

Buckner, R. L., Krienen, F. M., Castellanos, A., Diaz, J. C., & Yeo, T. T. (2011). The organization of the human cerebellum estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. Journal of Neurophysiology, 106(5), 2322–2345. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00339.2011

Capra, V., Iacomino, M., Accogli, A., Pavanello, M., Zara, F., Cama, A., & De Marco, P. (2019). Chiari malformation type I: What information from the genetics? Child’s Nervous System, 35(10), 1665–1671. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-019-04322-w

Chai, Z., Xue, X., Fan, H., Sun, L., Cai, H., Ma, Y., Ma, C., & Zhou, R. (2018). Efficacy of posterior fossa decompression with duraplasty for patients with Chiari malformation type I: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Neurosurgery, 113, 357–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.02.092

Chatrath, A., Marino, A., Taylor, D., Elsarrag, M., Soldozy, S., & Jane, J. A., Jr. (2019). Chiari I malformation in children – The natural history. Child’s Nervous System, 35(10), 1793–1799. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-019-04310-0

Chen, J., Li, Y., Wang, T., Gao, J., Xu, J., Lai, R., & Tan, D. (2017). Comparison of posterior fossa decompression with and without duraplasty for the surgical treatment of Chiari malformation type I in adult patients: A retrospective analysis of 103 patients. Medicine, 96(4), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000005945

Crittenden, J., Stephenson, T., Harty, S., Cyranowski, J., Friedlander, R., Guerrero, E., Pardini, J., & Henry, L. (2017, October 25–28). Cognition and affect among individuals with Chiari malformation type I: An examination of memory, anxiety and depression [poster]. Annual Meeting of the National Academy of Neuropsychology, Boston, USA. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acx076

D’Angelo, E., & Casali, S. (2013). Seeking a unified framework for cerebellar function and dysfunction: From circuit operations to cognition. Frontiers in Neural Circuits, 6(116), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncir.2012.00116

Del Casale, A., Serata, D., Rapinesi, C., Simonetti, A., Tamorri, S. M., Comparelli, A., De Carolis, A., Savoja, V., Kotzalidis, G. D., Sani, G., Tatarelli, R., & Girardi, P. (2012). Psychosis risk syndrome comorbid with panic attack disorder in a cannabis-abusing patient affected by Arnold-Chiari malformation type I. General Hospital Psychiatry, 34(6), 702.e5–702.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.12.008

Fischbein, R., Saling, J. R., Marty, P., Kropp, D., Meeker, J., Amerine, J., & Chyatte, M. R. (2015). Patient-reported Chiari malformation type I symptoms and diagnostic experiences: A report from the national Conquer Chiari Patient Registry database. Neurological Sciences, 36(9), 1617–1624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-015-2219-9

Gabrielli, O., Coppa, G. V., Manzoni, M., Carloni, I., Kantar, A., Maricotti, M., & Salvolini, U. (1998). Minor cerebral alterations observed by magnetic resonance imaging in syndromic children with mental retardation. European Journal of Radiology, 27(2), 139–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0720-048X(97)00040-5

García, M., Amayra, I., Lázaro, E., López-Paz, J. F., Martínez, O., Pérez, M., Berrocoso, S., & Al-Rashaida, M. (2018a). Comparison between decompressed and non-decompressed Chiari malformation type I patients: A neuropsychological study. Neuropsychologia, 121, 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2018.11.002

García, M., Amayra, I., López-Paz, J. F., Martínez, O., Lázaro, E., Pérez, M., Berrocoso, S., Al-Rashaida, M., & Infante, J. (2020a). Social cognition in Chiari malformation type I: A preliminary characterization. Cerebellum, 19(3), 392–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-020-01117-7

García, M., Eppelheimer, M., Houston, J. R., Houston, M. L., Nwotchouang, B. S. T., Kaut, K. P., Labuda, R., Bapuraj, J. R., Maleki, J., Klinge, P. M., Vorster, S., Luciano, M. G., Loth, F., & Allen, P. A. (2022). Adult age differences in self-reported pain and anterior CSF space in Chiari malformation. Cerebellum, 21(2), 194–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-021-01289-w

García, M., Lázaro, E., Amayra, I., López-Paz, J. F., Martínez, O., Pérez, M., Berrocoso, S., Al-Rashaida, M., & Infante, J. (2020b). Analysis of visuospatial abilities in Chiari malformation type I. Cerebellum, 19(1), 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-019-01056-y

García, M., Lázaro, E., López-Paz, J. F., Martínez, O., Pérez, M., Berrocoso, S., Al-Rashaida, M., & Amayra, I. (2018b). Cognitive functioning in Chiari malformation type I without posterior fossa surgery. Cerebellum, 17(5), 564–574. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-018-0940-7

Garcia, M. A., Allen, P. A., Li, X., Houston, J. R., Loth, F., Labuda, R., & Delahanty, D. L. (2019). An examination of pain, disability, and the psychological correlates of Chiari malformation pre- and post-surgical correction. Disability and Health Journal, 12(4), 649–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2019.05.004

Grosso, S., Scattolini, R., Paolo, G., Di Bartolo, R. M., Morgese, G., & Balestri, P. (2001). Association of Chiari I malformation, mental retardation, speech delay, and epilepsy: A specific disorder? Neurosurgery, 49(5), 1099–1104. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006123-200111000-00015

Guell, X., Hoche, F., & Schmahmann, J. D. (2015). Metalinguistic deficits in patients with cerebellar dysfunction: Empirical support for the dysmetria of thought theory. Cerebellum, 14(1), 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-014-0630-z

Guell, X., & Schmahmann, J. D. (2020). Cerebellar functional anatomy: A didactic summary based on human fMRI evidence. Cerebellum, 19(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-019-01083-9

Haapanen, M. L. (2007). CHERI: Time to identify the syndrome? Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 18(2), 369–373. https://doi.org/10.1097/scs.0b013e3180336075

Habas, C., Kamdar, N., Nguyen, D., Prater, K., Beckmann, C. F., Menon, V., & Greicius, M. D. (2009). Distinct cerebellar contributions to intrinsic connectivity networks. Journal of Neuroscience, 29(26), 8586–8594. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1868-09.2009

Hoche, F., Guell, X., Vangel, M. G., Sherman, J. C., & Schmahmann, J. D. (2018). The cerebellar cognitive affective/Schmahmann syndrome scale. Brain, 141(1), 248–270. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awx317

Houston, J. R., Allen, P. A., Rogers, J. M., Lien, M. C., Allen, N. J., Hughes, M. L., Bapuraj, J. R., Eppelheimer, M. S., Loth, F., Stoodley, M. A., Vorster, S. J., & Luciano, M. G. (2019). Type I Chiari malformation, RBANS performance, and brain morphology: Connecting the dots on cognition and macrolevel brain structure. Neuropsychology, 33(5), 725–738. https://doi.org/10.1037/neu0000547

Houston, J. R., Hughes, M. L., Bennett, I. J., Allen, P. A., Rogers, J. M., Lien, M. C., Stoltz, H., Sakaie, K., Loth, F., Maleki, J., Vorster, S. J., & Luciano, M. G. (2020). Evidence of neural microstructure abnormalities in type I Chiari malformation: Associations among fiber tract integrity, pain, and cognitive dysfunction. Pain Medicine, pnaa094. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnaa094

Houston, J. R., Hughes, M. L., Lien, M. C., Martin, B. A., Loth, F., Luciano, M. G., Vorster, S., & Allen, P. A. (2018). An electrophysiological study of cognitive and emotion processing in type I Chiari malformation. Cerebellum, 17(4), 404–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-018-0923-8

Houston, J. R., Maleki, J., Loth, F., Klinge, P. M., & Allen, P. A. (2022). Influence of pain on cognitive dysfunction and emotion dysregulation in Chiari malformation Type I. In M. Adamaszek, M. Manto, and D. Schutter (Eds.), The emotional cerebellum (pp. 155–178). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99550-8_11

Houston, M. L., Houston, J. R., Sakaie, K., Klinge, P. M., Vorster, S., Luciano, M., Loth, F., & Allen, P. A. (2021). Functional connectivity abnormalities in Type I Chiari: Associations with cognition and pain. Brain Communications, 3(3). https://doi.org/10.1093/braincomms/fcab137

Klein, R., Hopewell, C. A., & Oien, M. (2014). Chiari malformation type I: A neuropsychological case study. Military Medicine, 179(6), 712–718. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00227

Kraan, C. (2017). Cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. In N. Rinehart, J. Bradshaw, & P. Enticott (Eds.), Developmental disorders of the brain (pp. 25–43). Routledge.

Krishna, V., Sammartino, F., Yee, P., Mikulis, D., Walker, M., Elias, G., & Hodaie, M. (2016). Diffusion tensor imaging assessment of microstructural brainstem integrity in Chiari malformation type I. Journal of Neurosurgery, 125(5), 1112–1119. https://doi.org/10.3171/2015.9.JNS151196

Kumar, A., Pruthi, N., Devi, B. I., & Gupta, A. K. (2018). Response of syrinx associated with Chiari I malformation to posterior fossa decompression with or without duraplasty and correlation with functional outcome: A prospective study of 22 patients. Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice, 9(4), 587–592. https://doi.org/10.4103/jnrp.jnrp_10_18

Kumar, M., Rathore, R. K., Srivastava, A., Yadav, S. K., Behari, S., & Gupta, R. K. (2011). Correlation of diffusion tensor imaging metrics with neurocognitive function in Chiari I malformation. World Neurosurgery, 76(1–2), 189–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2011.02.022

Kurtcan, S., Alkan, A., Yetis, H., Tuzun, U., Aralasmak, A., Toprak, H., & Ozdemir, H. (2018). Diffusion tensor imaging findings of the brainstem in subjects with tonsillar ectopia. Acta Neurologica Belgica, 118(1), 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13760-017-0792-9

Labuda, R., Nwotchouang, B. S. T., Ibrahimy, A., Allen, P. A., Oshinski, J. N., Klinge, P., & Loth, F. (2022). A new hypothesis for the pathophysiology of symptomatic adult Chiari malformation Type I. Medical Hypotheses, 158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2021.110740

Lacy, M., Ellefson, S. E., DeDios-Stern, S., & Frim, D. M. (2016). Parent-reported executive dysfunction in children and adolescents with Chiari malformation type 1. Pediatric Neurosurgery, 51(5), 236–243. https://doi.org/10.1159/000445899

Lacy, M., Parikh, S., Costello, R., Bolton, C., & Frim, D. M. (2019). Neurocognitive functioning in unoperated adults with Chiari malformation type I. World Neurosurgery, 126, 641–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.02.105

Langridge, B., Phillips, E., & Choi, D. (2017). Chiari malformation type 1: A systematic review of natural history and conservative management. World Neurosurgery, 104, 213–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2017.04.082

Lawrence, B. J., Urbizu, A., Allen, P. A., Loth, F., Tubbs, R. S., Bunck, A. C., Kröger, J. R., Rocque, B. G., Madura, C., Chen, J. A., Luciano, M. G., Ellenbogen, R. G., Oshinski, J. N., Iskandar, B. J., & Martin, B. A. (2018). Cerebellar tonsil ectopia measurement in type I Chiari malformation patients show poor interoperator reliability. Fluids and Barriers of the CNS, 15(1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12987-018-0118-1

Lázaro, E., García, M., Ibarrola, A., Amayra, I., López-Paz, J. F., Martínez, O., Pérez, M., Berrocoso, S., Al-Rashaida, M., Rodríguez, A. A., Fernández, P., & Luna, P. M. (2018). Chiari type I malformation associated with verbal fluency impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_JSLHR-S-17-0465

Leiner, H. C., Leiner, A. L., & Dow, R. S. (1986). Does the cerebellum contribute to mental skills? Behavioral Neuroscience, 100(4), 443–454. https://doi.org/10.1037//0735-7044.100.4.443

Leiner, H. C., Leiner, A. L., & Dow, R. S. (1993). Cognitive and language functions of the human cerebellum. Trends in Neurosciences, 16(11), 444–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-2236(93)90072-T

Maher, C. O. (2020). Natural history of Chiari malformations. In R. S. Tubbs, M. Turgut, and W. J. Oakes (Eds.), The Chiari malformations (pp. 275–287). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44862-2_22

Mahgoub, N., Avari, J., & Francois, D. (2012). A case of Arnold-Chiari malformation associated with dementia. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 24(2), 44–45. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11050102

Manto, M., & Christian, H. (2013). Chiari malformations. In M. Manto, D. L. Gruol, J. D. Schmahmann, N. Koibuchi and F. Rossi (Eds.), Handbook of the Cerebellum and Cerebellar Disorders (pp. 1873–1885). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1333-8

Marin-Padilla, M., & Marin-Padilla, T. M. (1981). Morphogenesis of experimentally induced Arnold-Chiari malformation. Journal of Neurological Sciences, 50(1), 29–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-510X(81)90040-X

Markunas, C. A., Ashley-Koch, A. E., & Gregory, S. G. (2020). Genetics of the Chiari I and II malformations. In R. S. Tubbs, M. Turgut, and W. J. Oakes (Eds.), The Chiari Malformations (pp. 289–297). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44862-2_23

Massimi, L., Peppucci, E., Peraio, S., & Di Rocco, C. (2011). History of Chiari type I malformation. Neurological Sciences, 32(Suppl 3), 263–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-011-0700-7

Massimi, L., Peretta, P., Erbetta, A., Solari, A., Farinotti, M., Ciaramitaro, P., Saletti, V., Caldarelli, M., Canheu, A. C., Celada, C., Chiapparini, L., Chieffo, D., Cinalli, G., Di Rocco, F., Furlanetto, M., Giordano, F., Jallo, G., James, S., Lanteri, P., ... & Valentini, L. (2021). Diagnosis and treatment of Chiari malformation type 1 in children: The international consensus document. Neurological Sciences, 43(2), 1311–1326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-021-05317-9

Meadows, J., Guarnieri, M., Miller, K., Haroun, R., Kraut, M., & Carson, B. S. (2001). Type I Chiari malformation: A review of the literature. Neurosurgery Quarterly, 11(3), 220–229. https://doi.org/10.1097/00013414-200109000-00005

Meeker, J., Amerine, J., Kropp, D., Chyatte, M., & Fischbein, R. (2015). The impact of Chiari malformation on daily activities: A report from the national Conquer Chiari Patient Registry database. Disability and Health Journal, 8(4), 521–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2015.01.003

Mestres, O., Poca, M. A., Solana, E., Radoi, A., Quintana, M., Force, E., & Sahuquillo, J. (2012). Evaluación de la calidad de vida en los pacientes con una malformación de Chiari tipo I. Estudio piloto en una cohorte de 67 pacientes. Revista de Neurología, 55(3), 148–156. https://doi.org/10.33588/rn.5503.2012196

Mueller, D. M., & Oro’, J. J. (2005). Prospective analysis of self-perceived quality of life before and after posterior fossa decompression in 112 patients with Chiari malformation with or without syringomyelia. Neurosurgical Focus, 18(2), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3171/foc.2005.18.2.11

Novegno, F. (2019). Clinical diagnosis - part II: What is attributed to Chiari I. Child’s Nervous System, 35(10), 1681–1693. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-019-04192-2

Novegno, F., Caldarelli, M., Massa, A., Chieffo, D., Massimi, L., Pettorini, B., Tamburrini, G., & Di Rocco, C. (2008). The natural history of the Chiari type I anomaly. Journal of Neurosurgery. Pediatrics, 2(3), 179–187. https://doi.org/10.3171/PED/2008/2/9/179

Öktem, H., Dilli, A., Kürkçüoglu, A., Soysal, H., Yazici, C., & Pelin, C. (2016). Prevalence of Chiari type I malformation on cervical magnetic resonance imaging: A retrospective study. Anatomy, 10(1), 40–45. https://doi.org/10.2399/ana.15.039

Parker, S. L., Godil, S. S., Zuckerman, S. L., Mendenhall, S. K., Wells, J. A., Shau, D. N., & McGirt, M. J. (2013). Comprehensive assessment of 1-year outcomes and determination of minimum clinically important difference in pain, disability, and quality of life after suboccipital decompression for Chiari malformation I in adults. Neurosurgery, 73(4), 569–581. https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0000000000000032

Pearce, M., Oda, N., Mansour, A., & Bhalerao, S. (2006). Cognitive disorder NOS with Arnold-Chiari I malformation. Psychosomatics, 47(1), 88–89. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psy.47.1.88

Rindler, R. S., & Chern, J. J. (2020). Newer subsets: Chiari 1.5 and Chiari 0 malformations. In R. S. Tubbs, M. Turgut, and W. J. Oakes (Eds.), The Chiari Malformations (pp. 41–46). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44862-2_3

Riva, D., Usilla, A., Saletti, V., Esposito, S., & Bulgheroni, S. (2011). Can Chiari malformation negatively affect higher mental functioning in developmental age? Neurological Sciences, 32(Suppl 3), 307–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-011-0779-x

Rogers, J. M., Savage, G., & Stoodley, M. A. (2018). A systematic review of cognition in Chiari I malformation. Neuropsychology Review, 28(2), 176–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-018-9368-6

Sari, S. A., & Ozum, U. (2021). The executive functions, intellectual capacity, and psychiatric disorders in adolescents with Chiari malformation type 1. Child’s Nervous System, 37(7), 2269–2277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-021-05085-z

Schmahmann, J. D. (2019). The cerebellum and cognition. Neuroscience Letters, 688, 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2018.07.005

Schmahmann, J. D., Guell, X., Stoodley, C. J., & Halko, M. A. (2019). The theory and neuroscience of cerebellar cognition. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 42, 337–364. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-neuro-070918-050258

Schmahmann, J. D., & Sherman, J. C. (1998). The cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. Brain, 121(Pt 4), 561–579. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/121.4.561

Seaman, S. C., Streese, C. D., Manzel, K., Kamm, J., Menezes, A. H., Tranel, D., & Dlouhy, B. J. (2021). Cognitive and psychological functioning in Chiari malformation type I before and after surgical decompression - A prospective cohort study. Neurosurgery, 89(6), 1087–1096. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyab353

Smith, B. W., Strahle, J., Bapuraj, J. R., Muraszko, K. M., Garton, H. J., & Maher, C. O. (2013). Distribution of cerebellar tonsil position: Implications for understanding Chiari malformation. Journal of Neurosurgery, 119(3), 812–819. https://doi.org/10.3171/2013.5.JNS121825

Steinberg, S. N., Greenfield, J. P., & Perrine, K. (2020). Neuroanatomic correlates for the neuropsychological manifestations of Chiari malformation type I. World Neurosurgery, 136, 462–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2020.01.149

Stephenson, T., Crittenden, J., Harty, S., Cyranowski, J., Friedlander, R., Guerrero, E., Pardini, J., & Henry, L. (2017, October 25–28). Cognition and affect among individuals with Chiari malformation type I: An examination of executive function and psychological distress [poster]. Annual Meeting of the National Academy of Neuropsychology, Boston, USA. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acx076

Stoodley, C. J., MacMore, J. P., Makris, N., Sherman, J. C., & Schmahmann, J. D. (2016). Location of lesion determines motor vs. cognitive consequences in patients with cerebellar stroke. NeuroImage. Clinical, 12, 765–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2016.10.013

Stoodley, C. J., Valera, E. M., & Schmahmann, J. D. (2012). Functional topography of the cerebellum for motor and cognitive tasks: An fMRI study. NeuroImage, 59(2), 1560–1570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.065

Tubbs, R. S., Turgut, M., & Oakes, W. J. (2020). A history of the Chiari malformations. In R. S. Tubbs, M. Turgut, and W. J. Oakes (Eds.), The Chiari malformations (pp. 1–20). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44862-2_1

Tubbs, R. S., & Turgut, M. (2020). Defining the Chiari malformations: Past and newer classifications. In R. S. Tubbs, M. Turgut, and W. J. Oakes (Eds.), The Chiari malformations (pp. 21–39). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44862-2_2

Urbizu, A., Khan, T. N., & Ashley-Koch, A. E. (2017). Genetic dissection of Chiari malformation type 1 using endophenotypes and stratification. Journal of Rare Diseases Research and Treatment, 2(2), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.29245/2572-9411/2017/2.1082

Urbizu, A., Toma, C., Poca, M. A., Sahuquillo, J., Cuenca-León, E., Comand, B., & Macaya, A. (2013). Chiari malformation type I: A case-control association stud of 58 developmental genes. PLoS ONE, 8(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0057241

Vernooij, M. W., Ikram, M. A., Tanghe, H. L., Vincent, A. J., Hofman, A., Krestin, G. P., Niessen, W. J., Breteler, M. M. B., & van der Lugt, A. (2007). Incidental findings on brain MRI in the general population. The New England Journal of Medicine, 357(18), 1821–1828. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa070972

Yilmaz, Y., Karademir, M., Caygin, T., Yağcıoğlu, O. K., Özüm, Ü., & Kuğu, N. (2022). Executive functions, intellectual capacity, and psychiatric disorders in adults with type 1 Chiari malformation. World Neurosurgery, 168, e607–e612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2022.10.058

Zhao, J. L., Li, M. H., Wang, C. L., & Meng, W. (2016). A systematic review of Chiari I malformation: Techniques and outcomes. World Neurosurgery, 88, 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2015.11.087

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.G. conceived of the presented idea and wrote the manuscript with support from I.A., M.P., M.S., and P.A.. M.G., I.A., and M.P. contributed to methodological issues. O.M. and J.L. supervised the study and helped shape the research. All authors provided critical feedback and reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

García, M., Amayra, I., Pérez, M. et al. Cognition in Chiari Malformation Type I: an Update of a Systematic Review. Neuropsychol Rev (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-023-09622-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-023-09622-2