Abstract

Feedback of neuropsychological test results to patients and family members include psychoeducation and implications for daily life. This scoping review aimed to provide an overview of the literature on neuropsychological feedback and to offer clinical recommendations. In accordance with formal scoping review methodology, PubMed, PsycInfo, Web of Science, CINAHL, and Embase databases were searched. Studies were included if they reported on neuropsychological feedback, if full papers were available, and if they included human participants. All languages were included, and no limit was placed on the year of publication. Of the 2,173 records screened, 34 publications met the inclusion criteria. Five additional publications were included after cross-referencing. An update of the search led to the inclusion of two additional papers. Of these 41 publications, 26 were research papers. Neuropsychological feedback is provided for a wide spectrum of diagnoses and usually given in-person and has been related to optimal a positive effect on patient outcomes (e.g. increase the quality of life). Most papers reported on satisfaction and found that satisfaction with an NPA increased when useful feedback was provided. However, information retention was found to be low, but communication aids, such as written information, were found to be helpful in improving retention. The current review demonstrated the benefits of neuropsychological feedback and that this should be part of standard clinical procedures when conducting a neuropsychological assessment. Further research on the benefits of neuropsychological feedback and how to improve information provision would enrich the neuropsychological literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

An important role of healthcare providers is to deliver feedback from diagnostic findings and medical information to patients. A neuropsychological assessment (NPA) evaluates the cognitive performance of a patient and can provide insight into cognitive strengths and weaknesses (Lezak et al., 2012). In this study, explaining neuropsychological assessment results to patients and family members is defined as neuropsychological feedback. To our knowledge, this definition has been predominantly used in the literature. However, other terms have also been used (e.g., neuropsychological testing feedback). The goal of neuropsychological feedback is to help patients and family members understand the results and the implications for daily life functioning (Postal & Armstrong, 2013). Furthermore, neuropsychological feedback gives the opportunity to evaluate rehabilitation or treatment planning, provide support to patients and family members who might experience difficulties with adapting to a diagnosis, offer guidelines for decision-making, and answer questions or concerns patients may have about their NPA results (Brenner, 2003; Gorske & Smith, 2009). Giving feedback has been recommended by international clinical research groups and ethical guidelines state that a psychologist must undertake a reasonable attempt to explain the results of their assessment (Baxendale et al., 2019; Wilson et al., 2015; American Psychological Association, 2017; Baxendale & Thompson, 2010). Traditionally, neuropsychological feedback received little scientific attention and was not always part of clinical practice. Only a few studies at the end of the 80s have described the possible added value of giving neuropsychological feedback, and argued that patients who received valuable feedback were more satisfied with the NPA (Allen et al., 1986; Bennett-Levy et al., 1994). Other authors evaluated the effect of receiving personalized information in a group of 28 patients, which also included neuropsychological test results, and demonstrated that this resulted in to greater effort in therapy and more satisfaction with rehabilitation treatment (Pegg et al., 2005). Nearing the end of the 00s the number of publications increased that focused solely on the benefits of neuropsychological feedback. It was also shown that neuropsychological feedback has since become more embedded in standard practice (Westervelt et al., 2007). In a recent study in 218 patients from a neuropsychological outpatient clinic, neuropsychological feedback was shown to lead to improved quality of life, better comprehension of the medical condition, and an improved ability to cope with that condition (Rosado et al., 2018). In another study in 31 patients with ADHD or a mood disorder, providing feedback also resulted in less psychiatric and cognitive symptoms, and improved self-efficacy (Lanca et al., 2019). To our knowledge, research evaluating the benefits of neuropsychological feedback is limited. Due to the increase in publications regarding this topic in the past ten years a scoping review is warranted. It is important to gain more insight into what is known about neuropsychological feedback to improve quality of care. This scoping review aims to provide an overview (e.g., study types, methods used, results, quality of papers) about neuropsychological feedback. Furthermore, another aim is to offer recommendations for clinical practice.

Methods

Design

A preliminary literature search resulted in diversity of methods and multiple sources concerning neuropsychological feedback. Consequently, a scoping review was chosen over a systematic review due to the broader approach, as scoping reviews include multiple sources, such as studies with different designs, opinion or position papers, and gray literature (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005; Peters et al., 2015). A scoping review is used to provide an overview of the literature in the area of interest, to identify gaps of knowledge in the evidence base and to summarize relevant findings (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005). The current review was guided by the methodological framework described by Arksey and O'Malley (2005) and additional recommendations of Levac et al. (2010). This framework consisted of five stages guiding the scoping process of identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, study selection, charting the data, and summarizing and reporting the results (Levac et al., 2010). Furthermore, the PRISMA checklist for scoping reviews was used as reporting guideline (Tricco et al., 2018). Although a quality appraisal is not often applied in scoping reviews, we opted to use the Mixed Method Appraisal Tool 2018 version (Pace et al., 2012). This is a reliable and efficient critical appraisal tool with five criteria per research design to review the quality of methodology in systematic reviews and has been used in prior scoping reviews (Breneol et al., 2017; Bieber et al., 2019).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included books, book chapters, and research articles reporting on providing neuropsychological feedback to patients or family members (e.g., not studies that focused on broader assessment practices such as rehabilitation programs). All types of research designs, patient groups, and languages were included. No restrictions were made on year of publication. Research papers were excluded when no results were reported on neuropsychological feedback. Books, book chapters and opinion or position papers were excluded if neuropsychological feedback was not included as the main topic. Papers were also excluded if no full paper was available (e.g., conference abstracts) or in the case of nonhuman studies.

Data Sources and Search Strategy

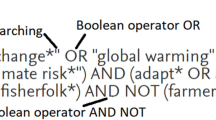

We searched the following databases: PubMed, PsycInfo, Web of Science, CINAHL, and Embase. A combination of free text terms in Title/Abstract and descriptor terms (e.g., MeSH terms) were used in the search string. The full search strategy for each database is provided in the supplementary material. The literature search was carried out on December 9, 2019. The search was updated on June 11, 2020.

Study Selection

Two authors (AG, IR) independently screened the titles and abstracts. They met in person after having screened the first 50 abstracts to discuss challenges and uncertainties related to study selection. After completion of abstract screening, the interrater reliability was therefore excellent (Cohen’s k = 0.89) (Altman, 1990). Afterwards, one author (AG) evaluated all full texts independently to determine eligibility for inclusion. The second author (IR) screened 10% (n = 8) of all full texts, randomly selected. This subsample was independently evaluated and no rater overlap was present. The interrater reliability was also excellent (Cohen’s k = 1.00). When it was uncertain whether to include a full text, this was discussed with the second author. Cross-referencing was used to determine if other relevant publications should be included.

Charting of Data

One of the reviewing authors (AG) extracted and summarized the data from the included publications. A data extraction plan was piloted for applicability and completeness and discussed among the other authors. The following was included in the chart: study design, setting, study population, sample size, methodology, intervention type and comparator, outcomes, outcome measurements, analysis, characteristics of NPA, characteristics of neuropsychological feedback, framework for feedback, key findings related to neuropsychological feedback, and key findings related to aids in neuropsychological feedback. The main topics were analyzed (qualitative content approach) and thematically classified and narratively described. The first draft of topics was discussed among the authors until consensus was reached. Quantitative analyses were not conducted due to the diversity of studies and the descriptive nature of most studies.

Results

The search yielded a total of 3,214 records; 2,173 remained after duplicates were removed. After screening the abstracts, 78 papers were evaluated for full text screening. A total of 34 papers were included, and five additional papers were identified through cross-referencing. The search was updated on June 11, 2020, which led to 84 extra records that were screened and three that underwent full text screening. Two papers were included from the updated search. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the selection process. In this study, the findings from 41 papers are summarized using a narrative report. An overview of the characteristics and outcomes of these publications is described in Table 1.

Type and Quality of Evidence

The following 41 publications were identified: 26 research papers, seven opinion papers, two position papers, three book chapters, two books, and one research protocol. In terms of study designs, the research papers included four qualitative studies, three randomized trials, five non-randomized trials, thirteen descriptive studies, and one mixed-methods study. Only the overall quality of the research papers could be assessed (see Table 4 Appendix B). Overall, the quality criteria were met; in some studies, subitems were not met (e.g., due to insufficient detailed information about the completeness of the data). In two studies, there was also a high risk for a nonresponse bias due to low response rates.

Characteristics of Neuropsychological Feedback

Most research papers used in-person feedback (Arffa & Knapp, 2008; Cheung et al., 2014; Connery et al., 2016; Fallows & Hilsabeck, 2013; Farmer & Brazeal, 1998; Foran et al., 2016; Holst et al., 2009; Kirkwood et al., 2016, 2017; Lanca et al., 2019; Lopez et al., 2008; Malla et al., 1997; Meth et al., 2016; Rosado et al., 2018; Tharinger & Pilgrim, 2012; Westervelt et al., 2007; Gruters et al., 2020; Martin & Schroeder, 2020), and most of the other publications recommended in-person feedback (Allen et al., 1986; Carone et al., 2010; Carone et al., 2013; Carone, 2017; Crosson, 2000; Gass & Brown, 1992; Gorske, 2007; Gorske & Smith, 2009; Green, 2000; Griffin & Christie, 2008; Postal & Armstrong, 2013; Ruppert & Attix, 2014). A minority gave feedback via phone (Stimmel et al., 2019), via telemedicine (Clement et al., 2001; Turner et al., 2012) or via a written report (Evans et al., 2019). Usually, feedback was given by the neuropsychologist a few weeks after the assessment. In four studies, this was given directly after testing (Meth et al., 2016; Kirkwood et al., 2016; Kirkwood et al., 2017; Connery et al., 2016).

The length and content of the feedback session was often not specified; when specified, it usually took approximately one hour and focused on cognitive strengths and weaknesses, the impacts of emotional functioning, the translation of results to daily life, and diagnostic issues and recommendations with compensatory strategies. A review of the included papers showed that neuropsychological feedback was provided for a wide spectrum of diagnoses (e.g., psychiatric, neurodevelopmental, brain injury, dementia, epilepsy, brain tumor). Most settings were neuropsychological outpatient clinics in a hospital. Whether neuropsychological feedback was always part of standard routine was not often specified. Two survey studies found that 26-44% of the patients received neuropsychological feedback and that the majority of all participants wanted more information (Bennett-Levy et al., 1994; Foran et al., 2016).

Satisfaction with Neuropsychological Services

Approximately half of the research papers (k = 13), mostly survey studies, focused on experiences and satisfaction with the NPA. Overall, high levels of satisfaction with the NPA and feedback sessions were described for both patients and family members (Connery et al., 2016; Foran et al., 2016; Kirkwood et al., 2016; Kirkwood et al., 2017; Pritchard et al., 2014; Tharinger & Pilgrim, 2012; Turner et al., 2012; Westervelt et al., 2007). Patients were more satisfied with the NPA when they received feedback, and if they experienced this as useful (Bennett-Levy et al., 1994). In one qualitative study, it was found that both positive (relief or confirmation due to NPA outcome and diagnosis) and negative experiences (feeling distressed due to awareness of cognitive complaints) coexisted during an NPA and diagnostic disclosure at a memory clinic (Gruters et al., 2020). The highest utility ratings of NPA were related to understanding cognitive strengths, weaknesses, and the relation between results and everyday behavior (Arffa & Knapp, 2008). Sometimes feedback was a mere confirmation of suspicions, but this was also seen as helpful (Westervelt et al., 2007). Other predictors of NPA satisfaction included perceptions of professional competence and rating of neuropsychological recommendations (Farmer & Brazeal, 1998). Only in a minority of the studies were participants less satisfied with the feedback session (Bodin et al., 2007; Foran et al., 2016). In one study, participants felt that feedback did not provide as much help as they had expected (Bodin et al., 2007). In another study, participants criticized neuropsychological feedback, because the results were difficult to understand, expressing the need for additional feedback sessions (Foran et al., 2016). Holst et al. (2009) found that low levels of satisfaction were related to low levels of self-esteem. Participants who were more satisfied were able to develop a more positive relationship with the examiner (Holst et al., 2009).

Recommendations Given in Neuropsychological Feedback

Both the research papers, opinion/position papers, books, and book chapters showed that the recommendations given most often by psychologists across diagnoses were focused on compensatory strategies, cognitive deficits, and health improvements. A survey study showed that most psychologists gave feedback and explanations about invalid test results (Martin & Schroeder, 2020). Quantitative studies showed that differences in recommendations were identified between diagnoses (e.g., more focused on support/independence or driving in dementia and on rehabilitation referrals in patients with traumatic brain injury) (Meth et al., 2019; Quillen et al., 2011). On average, six primary and eleven secondary recommendations were given (Arffa & Knapp, 2008). The majority of participants were positive and experienced recommendations as helpful (Quillen et al., 2011; Cheung et al., 2014). However, the overall adherence to recommendations was found to be approximately 40% in four different quantitative studies (Quillen et al., 2011; Cheung et al., 2014; Stimmel et al., 2019; Westervelt et al., 2007). Identified barriers were unwillingness to adapt to the recommendations of the family member, patient misunderstandings, a need for more information, disagreement with recommendations, a desire to speak with a physician regarding the recommendations, and level of difficulty obtaining recommended services (Cheung et al., 2014; Stimmel et al., 2019; Westervelt et al., 2007). Higher adherence rates were found for pharmacological management and recommendations related to patient safety (Westervelt et al., 2007; Stimmel et al., 2019).

Information Provision During Neuropsychological Feedback

One quantitative study and one mixed-methods study showed that neuropsychological feedback was not always remembered or understood (Bennett-Levy et al., 1994; Foran et al., 2016). Two randomized controlled trials showed that offering supplemental written information improved the free recall of recommendations (Meth et al., 2016; Fallows & Hilsabeck, 2013), especially in family members (Meth et al., 2016). However, the recall of diagnostic information did not differ between the groups with and without supplemental written information (Fallows & Hilsabeck, 2013; Meth et al., 2016). One survey study found that only one-third of the participants received a written report (Bennett-Levy et al., 1994), while in three studies (two survey studies, one non-randomized trial), it was found that the patients experienced the written report as helpful (Farmer & Brazeal, 1998; Bennett-Levy et al., 1994; Pritchard et al., 2014). A qualitative study and one opinion paper identified the following barriers in report writing: difficult to understand or unhelpful information, language proficiency, level and quality of education. It is important to consider ethnicity, country, native tongue, literacy, educational attainment and culture of origin, as these factors may contribute to barriers in understanding the feedback or terminology used, as well as treatment adherence. (Evans et al., 2019; Griffin & Christie, 2008). Some recommendations offered for report writing by these authors were to use as little information as possible, use in-text formatting, and organize headings by audience, diagnosis, and recommendations. Further advice was to be aware of cultural and linguistic differences, transparency, and translation of scores to daily life (Evans et al., 2019).

In one randomized controlled trial, a group of children and parents who received feedback with illustrative individualized stories reported that children experienced a greater sense of learning and collaboration, and a more positive relationship with the examiner compared to children and parents that received feedback without these stories. Parents experienced a greater sense of collaboration and a more positive relationship with their child and the examiner; they also reported higher satisfaction with the NPA (Tharinger & Pilgrim, 2012). No other studies focused on using visual aids in neuropsychological feedback; however, in one case study, one book, and two opinion papers, visual aids were recommended (Lopez et al., 2008; Postal & Armstrong, 2013; Carone et al., 2010; Gass & Brown, 1992). The use of props (e.g., brain model) or several shorter feedback sessions was recommended in two publications (Postal & Armstrong, 2013; Carone et al., 2013; Gass & Brown, 1992).

Postal and Armstrong (2013) described six principles of improving retention of neuropsychological feedback in their book: (1) simplicity (core message), (2) unexpectedness (novel information is better remembered), (3) concreteness (translation to daily life), (4) credibility (trusted source), (5) emotions (enhancing effects of emotions on memory), and (6) stories (transform passive listeners to active imaginers). They also advocate using motivational interviewing.

Neuropsychological Feedback and Patient Outcomes

Eight research papers explored the impact of neuropsychological feedback on patient outcomes. Patients with a mood disorder or ADHD reported reductions in psychiatric and cognitive symptoms and improvements in self-efficacy for general- and evaluation-specific goals one month after an NPA with feedback (Lanca et al., 2019). Two case studies of patients with anorexia nervosa or schizophrenia reported that feedback gave patients insight into their cognitive functioning so that they could deal with their disease in a different way in their daily life (Lopez et al., 2008; Malla et al., 1997). Patients who attended neuropsychological feedback sessions had a greater improvement in quality of life and an increased understanding of and ability to cope with their condition compared to those who did not attend these sessions (Rosado et al., 2018). Two studies found a decrease in self-reported post-concussive symptoms in both parents and children (Connery et al., 2016; Kirkwood et al., 2016). Greater initiation of parent behavior management and special education services and medication management were reported when parents of children with ADHD received neuropsychological feedback (Pritchard et al., 2014). After receiving feedback, the concerns of family members of patients with a stroke were related to safety, what the future will bring, knowing what to do when the patient is unable to perform a task, and dealing with the emotional changes of the patient (Belciug, 2006).

Feedback Frameworks and Clinical Recommendations

Table 2 shows an overview of the different feedback frameworks offered by six authors from one non-randomized study, three opinion papers, and two books. In all frameworks, some overlap can be identified: an explanation of the nature of NPA and rationale of feedback sessions, an explanation of strengths and weaknesses, and the provision of recommendations and compensatory strategies. Furthermore, in these feedback models, a collaborative approach using plain and understandable language without jargon is advocated.

Discussion

This scoping review identified 41 publications on neuropsychological feedback to patients and family members in diverse settings. Several themes related to neuropsychological feedback could be identified: characteristics of neuropsychological feedback, satisfaction with neuropsychological services, patient outcomes, recommendations given in neuropsychological feedback, information provision during neuropsychological feedback, feedback frameworks and clinical recommendations. A critical evaluation of the methodological quality of the included research papers showed that most met the criteria, but not all intervention studies included a control group, not all were randomized, and not all described the sample or outcome data in detail. Most prominent was the risk of response bias in the cross-sectional survey studies as a result of low response rates.

The majority of publications recommended or used in-person feedback. Approximately thirty years ago, Pope (1992) stated that feedback was the most neglected part of psychologists’ assessments. In our review, one survey study and one mixed-methods study evaluating clinical practice showed that neuropsychological feedback was not given to all patients (Bennett-Levy et al., 1994; Foran et al., 2016). However, one of these studies was carried out over 25 years ago. When reviewing broader psychological assessment practices (e.g., also considering personality assessment), two survey studies showed that the majority of psychologists gave in-person feedback, although this was not always a routine part of their assessment (Smith et al., 2007; Curry & Hanson, 2010). Based on these results, it seems that psychologists currently give feedback in psychological diagnostic procedure more often than 25 years ago. However, it is still not a clinical routine, and the content of neuropsychological feedback depends on the clinical context. Nonetheless, the potential clinical benefits of psychological feedback have been demonstrated, such as improved self-esteem, hopefulness, and reduced symptoms (Ackerman et al., 2000; Allen et al., 2003; Finn & Tonsager, 1997). Giving feedback also led to a better therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy (Ackerman et al., 2000; Hilsenroth et al., 2004). Furthermore, a meta-analysis showed that only when psychological assessment procedures were combined with personalized and collaborative feedback did clinically meaningful effects on treatment emerge (Poston & Hanson, 2010) In another study it was shown that psychological test validity was indistinguishable from medical tests validity, and that assessment feedback was related to increased patient well-being (Meyer et al., 2001; Finn & Tonsager, 1992; Newman & Greenway, 1997). Although research is lacking on the therapeutic value of collaborative neuropsychological feedback, it is highly likely that it has similar effects as in other psychological assessment fields. However, when looking at multidisciplinary practices, the diagnostic disclosure (based on all diagnostic assessments) is often given only by the medical specialist. Offering an additional consultation with a neuropsychologist to discuss NPA findings in multidisciplinary practices could be helpful in patients and offers the opportunity to improve information retention and answer remaining questions. Furthermore, it offers the opportunity to provide support and guidance due to the emotional impact of the diagnosis.

Consumer experience and satisfaction with NPA were the most reported outcomes in the current scoping review. Generally, positive experiences and high satisfaction with neuropsychological procedures were reported. Gaining more insight into consumer experiences and satisfaction is relevant, as it may lead to improvement of the quality of service and patient outcomes, such as reduced patient anxiety due to good communication (van Osch et al., 2017). However, the validity of satisfaction in treatment outcomes has been criticized as a result of not taking psychological factors, communication, and patient expectations into account (Verbeek, 2004; Hudak et al., 2003). In terms of an NPA, patient satisfaction was related to receiving feedback that was evaluated as valuable (Bennett-Levy et al., 1994). This is in line with the findings of Smith et al. (2007), who showed that patients appreciated that psychological feedback helped understand their problems, which could result in positive changes. However, not understanding or remembering neuropsychological feedback might negatively influence satisfaction. Therefore, Brenner (2003) has developed a framework that psychologists can use to increase the beneficial value of and satisfaction with psychological assessments: elimination of jargon, focus on referral questions, individualized assessment reports, emphasis on patient strengths, and including concrete recommendations.

The current review also showed that information retention of neuropsychological feedback was low. A few quantitative studies reported low percentages of information retention, especially recommendations were difficult to remember (Meth et al., 2016). This is in line with earlier studies that showed that the retention of medical information was generally low (Kessels, 2003). This is alarming, as adherence to treatment recommendations is related to understanding, recall, and satisfaction with the consultation (Ley, 1979). Understanding health information, also defined as health literacy, is important because low health literacy is the strongest predictor of poor health outcomes, such as more hospital admissions, higher mortality rates, and inadequate medication adherence (Berkman et al., 2011), as well as poor disease or care management (Graham & Brookey, 2008). Furthermore, patients with a low health literacy are less likely to take preventive measures or adopt a healthy lifestyle (Graham & Brookey, 2008). Remembering and understanding neuropsychological feedback may be even more difficult in patients who have a cognitive impairment. Retention might also be hampered by emotional arousal or valence related to receiving (bad news) or not receiving (good news) a diagnosis (Kensinger, 2009). On the one hand, receiving a ‘bad news’ diagnosis has profound emotional effect on both the patient and family members, such as feelings of stress and anxiety. It is very likely that this leads to lower recall of information. On the other hand, feeling relieved if the feared diagnosis is not confirmed might also negatively influence information retention. A few studies have explored the mode of information as a suitable target for communication aids. The current scoping review showed that offering supplemental written information might be helpful, but no studies have been conducted on whether visual aids could improve information retention in neuropsychological feedback. Some promising findings were seen in other fields, such as improved recall when using three-dimensional MRI models of the tumor and brain compared to two-dimensional models (Sezer et al., 2020). Furthermore, a systematic review showed better recall in multiple studies when visual aids were used (Watson & McKinstry, 2009). It is essential that neuropsychological feedback can be remembered so that it can lead to improved treatment outcomes. This review also showed that Motivational Interviewing principles might improve information retention as suggested by Postal and Armstrong (2013). In addition, motivational interviewing may also improve treatment adherence in rehabilitation, psychotherapy, and medication (Palacio et al., 2016; Tolchin et al., 2019; Suarez, 2011). Furthermore, the use of these techniques has been shown to reduce addictive behaviors (e.g., binge drinking, alcohol consumption) (Frost et al., 2018). Other applications of motivational interviewing have also been described, such as dealing with patient resistance (Gorske, 2007). By using these principles patients might understand the information and be more likely to change their behavior.

A strength of the current study is its use of the scoping review methodology to gain insight into a broad spectrum of literature on providing neuropsychological feedback. It synthesizes evidence on an emerging topic while using a systematic process that is both replicable, transparent and rigorous. Furthermore, the review has been carried out by experts in the field of clinical neuropsychology with the involvement of an expert librarian. Most scoping reviews do not include a critical appraisal of the quality of the included studies. However, we have included this to not only describe the scope of the research questions but also to give an impression of the validity.

Some limitations must be mentioned as well. One limitation is that reviews are time consuming, and new publications might have emerged since the search. However, we have recently updated the search, which resulted in the inclusion of two full papers. A second limitation is that although we have tried to discuss the most important findings, due to the limited space, some details might have not been described. Furthermore, the variation between the document types and range of data collection, methodology and analysis techniques made it sometimes difficult to present the results in a compact and integrated way.

Finally, future research should include more studies adopting a randomized controlled trial to gain more insight into the benefits of neuropsychological feedback. It would also be of interest to evaluate neuropsychological feedback in specific settings with a multidisciplinary nature, such as memory clinics. Furthermore, more attention is needed to train psychologists in providing neuropsychological feedback. It would be helpful if more attention could be given about this topic during graduate and postgraduate education courses of psychologists. The clinical recommendations offered in this paper could be used. Finally, more research is also needed focusing on how neuropsychological feedback could be best communicated to optimize information retention and treatment adherence. More research is needed to identify predictors of improved information retention (e.g., having multiple sessions, involving a family member, use of motivational interviewing principles). Furthermore, more studies are needed on how to best offer supplemental verbal or visual information to improve comprehension and retention of neuropsychological feedback.

Conclusion

Overall, the current scoping review shows that neuropsychological feedback is a vital and therapeutic component that may improve patients’ satisfaction with neuropsychological services. However, the content, frequency and type of feedback vary greatly across professionals. Furthermore, it should be stressed that information retention and adherence to recommendations is often poor, despite the provision of neuropsychological feedback. It is important that clinicians are aware of facilitators and barriers in offering neuropsychological feedback. In Table 3 we provide an overview of clinical recommendations is presented that can be used to improve retention, adherence, and the clinician-patient relationship through motivational interviewing principles. Although using communication aids seems promising, more research is warranted.

References

Ackerman, S. J., Hilsenroth, M. J., Baity, M. R., & Blagys, M. D. (2000). Interaction of therapeutic process and alliance during psychological assessment. Journal of Personality Assessment, 75(1), 82–109. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa7501_7

Allen, A., Montgomery, M., Tubman, J., Frazier, L., & Escovar, L. (2003). The effects of assessment feedback on rapport-building and self-enhancement processes. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 25(3), 165–182. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.25.3.lw7h84q861dw6ytj

Allen, J. G., Lewis, L., Blum, S., Voorhees, S., Jernigan, S., & Peebles, M. J. (1986). Informing psychiatric patients and their families about neuropsychological assessment findings. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 50(1), 64–74

Altman, D. G. (1990). Practical statistics for medical research: CRC press.

American Psychological Association (2017). Ethical principes of psychologists and code of conduct. Resource document. https://www.apa.org/ethics/code/. Accessed April 2020.

Arffa, S., & Knapp, J. A. (2008). Parental perceptions of the benefits of neuropsychological assessment in a neurodevelopmental outpatient clinic. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult, 15(4), 280–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/09084280802325181

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Baxendale, S., & Thompson, P. (2010). Beyond localization: the role of traditional neuropsychological tests in an age of imaging. Epilepsia, 51(11), 2225–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02710.x

Baxendale, S., Wilson, S. J., Baker, G. A., Barr, W., Helmstaedter, C., Hermann, B. P., et al. (2019). Indications and expectations for neuropsychological assessment in epilepsy surgery in children and adults. Epileptic Disorders, 21(3), 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1684/epd.2019.1065

Belciug, M. P. (2006). Concerns and anticipated challenges of family caregivers following participation in the neuropsychological feedback of stroke patients. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 29(1), 77–80. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mrr.0000185954.25423.b7

Bennett-Levy, J., Klein-boonschate, M. A., Batchelor, J., McCarter, R., & Walton, N. (1994). Encounters with Anna Thompson: The consumer’s experience of neuropsychological assessment. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 8(2), 219–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854049408401559

Berkman, N. D., Sheridan, S. L., Donahue, K. E., Halpern, D. J., & Crotty, K. (2011). Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 155(2), 97–107. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005

Bieber, A., Nguyen, N., Meyer, G., & Stephan, A. (2019). Influences on the access to and use of formal community care by people with dementia and their informal caregivers: a scoping review. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3825-z

Bodin, D., Beetar, J. T., Yeates, K. O., Boyer, K., Colvin, A. N., & Mangeot, S. (2007). A survey of parent satisfaction with pediatric neuropsychological evaluations. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 21(6), 884–898. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854040600888784

Breneol, S., Belliveau, J., Cassidy, C., & Curran, J. A. (2017). Strategies to support transitions from hospital to home for children with medical complexity: A scoping review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 72, 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.04.011

Brenner, E. (2003). Consumer-focused psychological assessment. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 34(3), 240–247. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.34.3.240

Carone, D. A. (2017). But the scores don’t show how i really function: A feedback method to reveal cognitive distortions regarding normal neuropsychological test performance. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult, 24(2), 160–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/23279095.2015.1116074

Carone, D. A., Bush, S. S., & Iverson, G. L. (2013). Providing feedback on symptom validity, mental health, and treatment in mild traumatic brain injury. Mild traumatic brain injury: Symptom validity assessment and malingering. (pp. 101–118). Springer Publishing Company.

Carone, D. A., Iverson, G. L., & Bush, S. S. (2010). A model to approaching and providing feedback to patients regarding invalid test performance in clinical neuropsychological evaluations. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 24(5), 759–778. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854041003712951

Cheung, L. L., Wakefield, C. E., Ellis, S. J., Mandalis, A., Frow, E., & Cohn, R. J. (2014). Neuropsychology reports for childhood brain tumor survivors: implementation of recommendations at home and school. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 61(6), 1080–1087. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.24940

Clement, P. F., Brooks, F. R., Dean, B., & Galaz, A. (2001). A neuropsychology telemedicine clinic. Military Medicine, 166(5), 382–384

Connery, A. K., Peterson, R. L., Baker, D. A., & Kirkwood, M. W. (2016). The impact of pediatric neuropsychological consultation in mild traumatic brain injury: A model for providing feedback after invalid performance. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 30(4), 579–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2016.1177596

Crosson, B. (2000). Application of neuropsychological assessment results. In R. D. Vanderploeg (Ed.), Clinician’s guide to neuropsychological assessment. (pp. 181–225). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Curry, K. T., & Hanson, W. E. (2010). National survey of psychologists’ test feedback training, supervision, and practice: A mixed methods study. Journal of Personality Assessment, 92(4), 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2010.482006

Evans, C. L., Pulsifer, M. B., & Grieco, J. A. (2019). Communication of neuropsychological results to caregivers of Latino immigrant children. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 5(1), 42–50. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000178

Fallows, R. R., & Hilsabeck, R. C. (2013). Comparing two methods of delivering neuropsychological feedback. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 28(2), 180–188. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acs142

Farmer, J. E., & Brazeal, T. J. (1998). Parent perceptions about the process and outcomes of child neuropsychological assessment. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult, 5(4), 194–201. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324826an0504_4

Finn, S. E., & Tonsager, M. E. (1992). Therapeutic effects of providing MMPI-2 test feedback to college students awaiting therapy. (Vol. 4, pp. 278-287). US: American Psychological Association.

Finn, S. E., & Tonsager, M. E. (1997). Information-gathering and therapeutic models of assessment: Complementary paradigms. Psychological Assessment, 9(4), 374–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.9.4.374

Foran, A., Millar, E., & Dorstyn, D. (2016). Patient satisfaction with a hospital-based neuropsychology service. Australian Health Review, 40(4), 447–452. https://doi.org/10.1071/ah15054

Frost, H., Campbell, P., Maxwell, M., O’Carroll, R. E., Dombrowski, S. U., Williams, B., et al. (2018). Effectiveness of Motivational Interviewing on adult behaviour change in health and social care settings: A systematic review of reviews. Public Library of Science One, 13(10), e0204890. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204890

Gass, C. S., & Brown, M. C. (1992). Neuropsychological test feedback to patients with brain dysfunction. Psychological Assessment, 4(3), 272–277. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.4.3.272

Gorske, T. T. (2007). Therapeutic neuropsychological assessment: A humanistic model and case example. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 48(3), 320–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167807303735

Gorske, T. T., & Smith, S. (2009). Collaborative therapeutic neuropsychological assessment. Springer Science + Business Media.

Graham, S., & Brookey, J. (2008). Do patients understand? The Permanente Journal, 12(3), 67–9. https://doi.org/10.7812/tpp/07-144

Green, J. (2000). Providing feedback and planning follow-up services. In J. Green (Ed.), Neuropsychological evaluation of the older adult: A clinician’s guidebook. (pp. 205–215). Academic Press.

Griffin, A., & Christie, D. (2008). Taking a systemic perspective on cognitive assessments and reports: reflections of a paediatric and adolescent psychology service. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 13(2), 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104507088343

Gruters, A. A. A., Christie, H. L., Ramakers, I., Verhey, F. R. J., Kessels, R. P. C., & de Vugt, M. E. (2020). Neuropsychological assessment and diagnostic disclosure at a memory clinic: A qualitative study of the experiences of patients and their family members. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2020.1749936

Hilsenroth, M. J., Peters, E. J., & Ackerman, S. J. (2004). The development of therapeutic alliance during psychological assessment: patient and therapist perspectives across treatment. Journal of Personality Assessment, 83(3), 332–344. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa8303_14

Holst, Y., Nyman, H., & Larsson, J.-O. (2009). Predictors of patient satisfaction with the feedback after a neuropsychological assessment. The Open Psychiatry Journal, 3, 50–55. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874354400903010050

Hudak, P. L., McKeever, P., & Wright, J. G. (2003). The metaphor of patients as customers: Implications for measuring satisfaction. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 56(2), 103–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00602-9

Kensinger, E. A. (2009). Remembering the details: Effects of emotion. Emotion Review, 1(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073908100432

Kessels, R. P. C. (2003). Patients’ memory for medical information. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 96(5), 219–222

Kirkwood, M. W., Peterson, R. L., Baker, D. A., & Connery, A. K. (2017). Parent satisfaction with neuropsychological consultation after pediatric mild traumatic brain injury. Child Neuropsychology, 23(3), 273–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/09297049.2015.1130219

Kirkwood, M. W., Peterson, R. L., Connery, A. K., Baker, D. A., & Forster, J. (2016). A pilot study investigating neuropsychological consultation as an intervention for persistent postconcussive symptoms in a pediatric sample. The Journal of Pediatrics, 169, 244-249.e241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.10.014

Lanca, M., Giuliano, A. J., Sarapas, C., Potter, A. I., Kim, M. S., West, A. L., et al. (2019). Clinical outcomes and satisfaction following neuropsychological assessment for adults: A community hospital prospective quasi-experimental study. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acz059

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

Ley, P. (1979). Memory for medical information. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 18(2), 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1979.tb00333.x

Lezak, M. D., Howieson, D. B., Bigler, E. D., & Tranel, D. (2012). Neuropsychological assessment (fifth. (edition). Oxford University Press.

Longley, W. A., Tate, R. L., & Brown, R. F. (2012). A protocol for measuring the direct psychological benefit of neuropsychological assessment with feedback in multiple sclerosis. Brain Impairment, 13(2), 238–255. https://doi.org/10.1017/BrImp.2012.20

Lopez, C., Roberts, M. E., Tchanturia, K., & Treasure, J. (2008). Using neuropsychological feedback therapeutically in treatment for anorexia nervosa: Two illustrative case reports. European Eating Disorders Review, 16(6), 411–420. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.866

Malla, A. K., Lazosky, A., McLean, T., Rickwood, A., Cheng, S., & Norman, R. M. G. (1997). Neuropsychological assessment as an aid to psychosocial rehabilitation in severe mental disorders. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 21(2), 169–173. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0095322

Martin, P. K., & Schroeder, R. W. (2020). Feedback with patients who produce invalid testing: Professional values and reported practices. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2020.1722243

Meth, M., Bernstein, J. P. K., Calamia, M., & Tranel, D. (2019). What types of recommendations are we giving patients? A survey of clinical neuropsychologists. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 33(1), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2018.1456564

Meth, M., Calamia, M., & Tranel, D. (2016). Does a simple intervention enhance memory and adherence for neuropsychological recommendations? Applied Neuropsychology: Adult, 23(1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/23279095.2014.996881

Meyer, G. J., Finn, S. E., Eyde, L. D., Kay, G. G., Moreland, K. L., Dies, R. R., et al. (2001). Psychological testing and psychological assessment: A review of evidence and issues. American Psychologist, 56(2), 128–165. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.2.128

Newman, M. L., & Greenway, P. (1997). Therapeutic effects of providing MMPI-2 test feedback to clients at a university counseling service: A collaborative approach. 9, 122-131. US: American Psychological Association.

Pace, R., Pluye, P., Bartlett, G., Macaulay, A. C., Salsberg, J., Jagosh, J., et al. (2012). Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Internationak Journal of Nursing Studies, 49(1), 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.07.002

Palacio, A., Garay, D., Langer, B., Taylor, J., Wood, B. A., & Tamariz, L. (2016). Motivational Interviewing improves medication adherence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of general internal medicine, 31(8), 929–940. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3685-3

Pegg, P. O., Auerbach, S. M., Seel, R. T., Buenaver, L. F., Kiesler, D. J., & Plybon, L. E. (2005). The impact of patient-centered information on patients’ treatment satisfaction and outcomes in traumatic brain injury rehabilitation. Rehabilitation Psychology, 50(4), 366–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/0090-5550.50.4.366

Peters, M. D., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evid-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1097/xeb.0000000000000050

Pope, K. S. (1992). Responsibilities in providing psychological test feedback to clients. 4, 268-271. US: American Psychological Association.

Postal, K. S., & Armstrong, K. (2013). Feedback that sticks: The art of effectively communicating neuropsychological assessment results. Oxford University Press.

Poston, J. M., & Hanson, W. E. (2010). Meta-analysis of psychological assessment as a therapeutic intervention. Psychological Assessment, 22(2), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018679

Pritchard, A. E., Koriakin, T., Jacobson, L. A., & Mahone, E. M. (2014). Incremental validity of neuropsychological assessment in the identification and treatment of youth with ADHD. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 28(1), 26–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2013.863978

Quillen, J., Crawford, E., Plummer, B., Bradley, H., & Glidden, R. (2011). Parental follow-through of neuropsychological recommendations for childhood-cancer survivors. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 28(5), 306–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454211418668

Rosado, D. L., Buehler, S., Botbol-Berman, E., Feigon, M., León, A., Luu, H., et al. (2018). Neuropsychological feedback services improve quality of life and social adjustment. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 32(3), 422–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2017.1400105

Ruppert, P. D., & Attix, D. K. (2014). Evaluation and treatment of geriatric neurocognitive disorders. In N. A. Pachana, & K. Laidlaw (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Clinical Geropsychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sezer, S., Piai, V., Kessels, R. P. C., & Ter Laan, M. (2020). Information recall in pre-operative consultation for glioma surgery using actual size three-dimensional models. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(11). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9113660

Smith, S. R., Wiggins, C. M., & Gorske, T. T. (2007). A survey of psychological assessment feedback practices. Assessment, 14(3), 310–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191107302842

Stimmel, M., Shagalow, S., Seng, E. K., Portnoy, J. G., Archetti, R., Mendelowitz, E., et al. (2019). Short report: Adherence to neuropsychological recommendations in patients with multiple sclerosis. The International Journal of MS Care, 21(2), 70–75. https://doi.org/10.7224/1537-2073.2017-089

Suarez, M. (2011). Application of motivational interviewing to neuropsychology practice: A new frontier for evaluations and rehabilitation. The Little Black Book of Neuropsychology. (pp. 863–871). Springer.

Tharinger, D. J., & Pilgrim, S. (2012). Parent and child experiences of neuropsychological assessment as a function of child feedback by individualized fable. Child Neuropsychology, 18(3), 228–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/09297049.2011.595708

Tolchin, B., Baslet, G., Martino, S., Suzuki, J., Blumenfeld, H., Hirsch, L. J., et al. (2019). Motivational Interviewing techniques to improve psychotherapy adherence and outcomes for patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 32(2), 125–131. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.19020045

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., et al. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Turner, T. H., Horner, M. D., Vankirk, K. K., Myrick, H., & Tuerk, P. W. (2012). A pilot trial of neuropsychological evaluations conducted via telemedicine in the Veterans Health Administration. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health, 18(9), 662–667. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2011.0272

van Osch, M., van Dulmen, S., van Vliet, L., & Bensing, J. (2017). Specifying the effects of physician’s communication on patients’ outcomes: A randomised controlled trial. Patient Education and Counseling, 100(8), 1482–1489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.03.009

Verbeek, J. (2004). Patient satisfaction: is it a measure for the outcome of care or the process of care? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 57(2), 217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.07.006

Watson, P. W., & McKinstry, B. (2009). A systematic review of interventions to improve recall of medical advice in healthcare consultations. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 102(6), 235–243. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2009.090013

Westervelt, H. J., Brown, L. B., Tremont, G., Javorsky, D. J., & Stern, R. A. (2007). Patient and family perceptions of the neuropsychological evaluation: How are we doing? The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 21(2), 263–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854040500519745

Wilson, S. J., Baxendale, S., Barr, W., Hamed, S., Langfitt, J., Samson, S., et al. (2015). Indications and expectations for neuropsychological assessment in routine epilepsy care: Report of the ILAE Neuropsychology Task Force, Diagnostic Methods Commission, 2013–2017. Epilepsia, 56(5), 674–681. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.12962

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Stefan Jongen (Maastricht University Library) for his advice and help in developing the search strategy.

Funding

This study was supported by an independent grant from the Noaber Foundation and Alzheimer Nederland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have made a significant contribution to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were reported by the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A Search Strategy

Pubmed

('neuropsychological assessment'[Title/Abstract] OR 'neuropsychological evaluation'[Title/Abstract] OR 'neuropsychology'[Title/Abstract] OR 'neuropsychologist'[Title/Abstract] OR 'neuropsychological'[Title/Abstract] OR neuropsychological test*[Title/Abstract] OR neuropsychological result*[Title/Abstract] OR "Neuropsychology/instrumentation"[Mesh] OR "Neuropsychology/methods"[Mesh] OR "Neuropsychology/organization and administration"[Mesh] OR "Neuropsychology/standards"[Mesh] OR "Neuropsychology/trends"[Mesh] OR "Neuropsychological Tests/instrumentation"[Mesh] OR "Neuropsychological Tests/methods"[Mesh] OR "Neuropsychological Tests/standards"[Mesh]) AND (feedback[Title/Abstract] OR recommendations[Title/Abstract] OR communicat*[Title/Abstract] OR "Feedback/instrumentation"[Mesh] OR "Feedback/methods"[Mesh] OR "Feedback, Psychological/instrumentation"[Mesh] OR "Feedback, Psychological/methods"[Mesh] OR "Feedback, Psychological/organization and administration"[Mesh] OR "Feedback, Psychological/standards"[Mesh] OR "Feedback, Psychological/trends"[Mesh] OR "Communication/diagnosis"[Mesh] OR "Communication/instrumentation"[Mesh] OR "Communication/methods"[Mesh] OR "Communication/organization and administration"[Mesh] OR "Communication/psychology"[Mesh] OR "Communication/standards"[Mesh] OR "Communication/trends"[Mesh]) AND (patient OR family members OR carers)

PsycInfo/CINAHL

(AB 'neuropsychological assessment' OR AB ‘neuropsychological evaluation’ OR AB ‘neuropsychology’ OR AB ‘neuropsychologist’ OR ‘AB ‘neuropsychological’ OR AB ‘neuropsychological test*’ OR AB ‘neuropsychological result*’ OR DE ‘neuropsychology’ OR DE ‘neuropsychological assessment’) AND

(AB ‘feedback’ OR AB ‘recommendations’ OR AB ‘communicat*’ OR DE ‘feedback’ OR DE ‘communication’) AND (‘patient’ OR ‘family members’ or ‘carers’)

Embase

(*neuropsychology/ or *neuropsychological test/ or (neuropsychological test or neuropsychological evaluation or neuropsychology or neuropsychologist or neuropsychological or neuropsychological test* or neuropsychological result*).ti,ab.) and (*psychological feedback/ or (feedback or recommendations or communicat*).ti,ab.) and (patient or family members or carers).mp.

Web of Science

TI=(neuropsychological assessment OR neuropsychological evaluation OR neuropsychology OR neuropsychologist OR neuropsychological OR neuropsychological test* OR neuropsychological result*) AND TS=(feedback OR recommendations OR communicat*) AND ALL=(patient OR family members OR carers)

Appendix B Quality Assessment

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gruters, A.A., Ramakers, I.H., Verhey, F.R. et al. A Scoping Review of Communicating Neuropsychological Test Results to Patients and Family Members. Neuropsychol Rev 32, 294–315 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-021-09507-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-021-09507-2