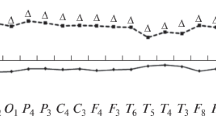

We analyzed changes in the spectral powers of different EEG frequency ranges and levels of coherence of the respective oscillations under conditions of passive perception of the smell of isoamyl acetate (pear essence) by humans in the resting state. Depending on a subjective estimate of the smell of isoamyl acetate, its presence per se caused increases in the mean levels of coherence of high-frequency a-subrange oscillations in all tested persons, which can be indicative of intensification of internal mental activity and increase in readiness to react. In the tested persons estimating the used olfactory stimulus as negative, the coherence of α2- and β1-oscillations in the central cortical areas and in the frontal and occipital zones decreased. In the tested persons with the positive subjective estimate of the isoamyl acetate smell, the coherence increased also in the a1-subrange during the action of this olfactory stimulus. Therefore, we obtained indications that activation of the olfactory analyzer is capable of changing the functioning of neuronal networks of the human brain in the resting state, and the pattern of these alterations partly depends on a subjective hedonic estimate of one smell or another.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

A. A. Cherninskii, I. G. Zima, N. Ye. Makarchouk, et al., “Modifications of EEG related to directed perception and analysis of olfactory information in humans,” Neurophysiology, 41, No. 1, 63-70 (2009).

S. S. Schiffman and C. A. Garlin, “Clinical physiology of taste and smell,” Ann. Rev. Nutrit., 13, 405-436 (1993).

A. D. Nguyen, M. E. Shenton, and J. J. Levitt, “Olfactory dysfunction in schizophrenia: a review of neuroanatomy and psychophysiological measurements,” Harvey Rev. Psychiat., 18, No. 5, 279-292 (2010).

B. Atanasova, J. Graux, W. El Hage, et al., “Olfaction: a potential cognitive marker of psychiatric disorders,” Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev., 32, No. 7, 1315-1325 (2008).

J. P. Kline, G. I. Schwartz, Z. V. Dikman, et al., “Electroencephalographic registration of low concentrations of isoamyl acetate,” Conscious. Cognit., 9, No. 1, 50-65 (2000).

L. Cui and W. J. Evans, “Olfactory event-related potentials to isoamyl acetate in congenital anosmia,” Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol., 102, No. 4, 303-306 (1998).

V. T. Troitskaia and O. S. Gladysheva, “Smell reception and neurogenesis in the olfactory epithelium,” Neurophysiology, 22, No. 4, 500-506 (1990).

K. Christoff, A. M. Gordon, J. Smallwood, et al., “Experience sampling during fMRI reveals default network and executive system contributions to mind wandering,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 106, No. 21, 8719-8724 (2009).

D. A. Fair, A. L. Cohen, N. U. Osenbach, et al., “The maturing architecture of the brain’s default network,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 105, No. 10, 4028-4032 (2008).

N. E. Sviderskaya, T. A. Korol’kova, and N. O. Nikolaeva, “Spatial-frequency structure of cortical processes in different intellectual activities in humans,” Fiziol. Cheloveka, 16, No. 5, 5-12 (1990).

A. P. Burgess and J. H. Gruzelier, “Localization of word and face recognition memory using topographical EEG,” Psychophysiology, 34, 7-16 (1997).

D. E. Everhart, “Low alpha power (7.5-9.5 Hz) changes during positive and negative affective learning,” Cognit., Affect., Behav. Neurosci., 3, No. 1, 39-45 (2003).

N. E. Sviderskaya and T. A. Korol’kova, “Spatial organization of electrical processes in the brain: problems and solutions,” Zh. Vyssh. Nerv. Deyat., 47, No. 5, 792-811 (1997).

A. K. Engel and P. Fries, “Beta-band oscillationssignalling the status quo?” Curr. Opin. Neurobiol., 20, No. 2, 156-165 (2010).

M. Kukleta, M. Brázdil, R. Roman, et al., “Cognitive network interactions and beta-2 coherence in processing non-target stimuli in visual oddball task,” Physiol. Res., 58, 139-148 (2009).

M. D. Greicius, B. Krasnow, A. L. Reiss, et al., “Functional connectivity in the resting brain: a network analysis of the default mode hypothesis,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 100, 253-258 (2003).

M. F. Mason, M. I. Norton, J. D. Van Horn, et al., “Wandering minds: The default network and stimulusindependent thought,” Science, 315, No. 5810, 393-395 (2007).

R. S. Herz, “A naturalistic analysis of autobiographical memories triggered by olfactory visual and auditory stimuli,” Chem. Senses, 29, No. 3, 217-224 (2004).

P. Sauseng, W. Klimesch, M. Schabus, and M. Doppelmayr, “Fronto-parietal EEG coherence in theta and upper alpha reflect central executive functions of working memory,” Int. J. Psychophysiol., 57, 97-103 (2005).

G. G. Knyazev, J. Y. Slobodskoj-Plusnin, A. V. Bocharov, et al., “The default mode network and EEG alpha oscillations: An independent component analysis,” Brain Res., 1402, 67-79 (2011).

D. E. Everhart, “Low alpha power (7.5-9.5 Hz) changes during positive and negative affective learning,” Cognit., Affect. Behav. Neurosci., 3, No. 1, 39-45 (2003).

F. Travis, “Comparison of coherence, amplitude, and eLORETA patterns during transcendental meditation and TM-sidhi practice,” Int. J. Psychophysiol., 81, 198-202 (2011).

A. Wrobel, “Beta activity: a carrier for visual attention,” Acta Neurobiol. Exp., 60, No. 2, 247-260 (2000).

I. Savic and H. Berglund, “Passive perception of odors and semantic circuits,” Human Brain Mapp., 21, No. 4, 271-278 (2004).

L. Theresa and A. White, “Second look at the structure of human olfactory memory,” Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci., 1170, 338-342 (2009).

T. Bitter, H. Gudziol, H. P. Burmeister, et al., “Anosmia leads to a loss of gray matter in cortical brain areas,” Chem. Senses, 35, No. 5, 407-415 (2010).

O. Sporns, Networks of the Brain, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts (2011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zima, I.G., Makarchouk, N.Y., Kryzhanovskii, S.A. et al. Effects of Passive Perception of Isoamyl Acetate Smell on the Resting-State EGG in Humans. Neurophysiology 46, 486–493 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11062-015-9478-1

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11062-015-9478-1