Abstract

Purpose

To gain insight into how patients with primary brain tumors experience MRI, follow-up protocols, and gadolinium-based contrast agent (GBCA) use.

Methods

Primary brain tumor patients answered a survey after their MRI exam. Questions were analyzed to determine trends in patients’ experience regarding the scan itself, follow-up frequency, and the use of GBCAs. Subgroup analysis was performed on sex, lesion grade, age, and the number of scans. Subgroup comparison was made using the Pearson chi-square test and the Mann–Whitney U-test for categorical and ordinal questions, respectively.

Results

Of the 100 patients, 93 had a histopathologically confirmed diagnosis, and seven were considered to have a slow-growing low-grade tumor after multidisciplinary assessment and follow-up. 61/100 patients were male, with a mean age ± standard deviation of 44 ± 14 years and 46 ± 13 years for the females. Fifty-nine patients had low-grade tumors. Patients consistently underestimated the number of their previous scans. 92% of primary brain tumor patients did not experience the MRI as bothering and 78% would not change the number of follow-up MRIs. 63% of the patients would prefer GBCA-free MRI scans if diagnostically equally accurate. Women found the MRI and receiving intravenous cannulas significantly more uncomfortable than men (p = 0.003). Age, diagnosis, and the number of previous scans had no relevant impact on the patient experience.

Conclusion

Patients with primary brain tumors experienced current neuro-oncological MRI practice as positive. Especially women would, however, prefer GBCA-free imaging if diagnostically equally accurate. Patient knowledge of GBCAs was limited, indicating improvable patient information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

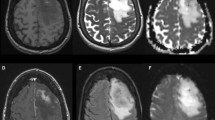

Patients with primary brain tumors, especially with gliomas, usually receive multiple MRI scans per year as standard care. Patients with a slow-growing low-grade glioma (LGG) may undergo dozens of MRI scans due to their chronic condition. Research endeavors towards faster and more informative MRI protocols are ongoing [1,2,3,4], but glioma MRI protocols remain lengthy and include gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCA). The patient opinion on radiological care is largely unknown, despite the vulnerability of glioma patients and the relevant implications for patients and physicians.

MRI is a crucial pillar of therapy planning and response evaluation in neuro-oncology [5]. Brain tumor MRI protocols tend to adhere to consensus recommendations [6]. Most guidelines include an initial follow-up interval between three to six months after the completion of therapy, depending on the tumor histology. The scanning interval should be decreased to four to eight weeks in case of possible disease progression [7]. However, patients with brain tumors undergo particularly long and frequent MRI scans, while many low-grade brain tumors remain stable for long periods [8,9,10]. Furthermore, the benefit of fixed interval imaging remains unclear [11, 12].

Contrast-enhanced T1 weighted imaging (CET1w), often including contrast-enhanced dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion imaging (DSC), is considered invaluable to the toolbox of neuroradiologists and is standard of care during the follow-up of brain tumors. However, research has shown long-term GBCA deposition, and current patient claims of GBCA-induced side effects are under investigation [13, 14]. Therefore, American and European pharmaco-safety agencies urge clinicians only to use GBCA when strictly necessary, but risk–benefit analyses for GBCA are awaited [15,16,17]. Many lesions never enhance or enhance without being high-grade brain tumors.

Against this backdrop, it becomes clear why neuroradiological research focuses on strategies to optimize imaging intervals. It also explores using advanced MRI sequences and artificial intelligence to shorten scan protocols and gain deeper insight into tumor biology [18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. This includes imaging without or with reduced GBCA, particularly for the low-grade tumor follow-up in the pediatric population [25,26,27].

The patient opinion on radiological care in brain tumor management is mainly unknown despite a general acknowledgement of the value of patient-centered research and shared decision-making [28, 29]. This includes patient opinions on GBCA use.

There is a knowledge gap regarding the opinion of the patient on neuro-oncological MRI and research developments in particular, which also has a negative impact on the planning of future MRI research lines.

To gain more insight into the patient perspective on neuro-oncological MRI, its follow-up, and the use of GBCAs and to draw conclusions on the patient-perceived urgency of current research lines, we performed a cross-sectional survey on patients with primary brain tumors.

Methods

Study design and participants

The local ethics committee approved the study. A questionnaire was designed in collaboration with our patient-reported experience measures department. One hundred patients were estimated as a sufficient sample size following the COSMIN study design checklist for patient-reported outcome measurement instruments [30].

Questionnaire targets were adult primary intra-axial brain tumor patients with at least 1 year of known diagnosis who had regular follow-up at our institution. The diagnosis had been histopathologically confirmed or was based on radiological phenotype and multidisciplinary consensus (“scan and wait”). Impairments due to tumor therapy were not an exclusion criterion, nor a selection criterion. All patients that had a neuro-oncological MRI scan and met all the inclusion-criteria were consecutively approached before their clinical MRI scan between 01-09-2021 and 04-08-2022. Patients needed to give informed consent before the clinically scheduled regular MRI scan and were interviewed directly after the scan. Patients with acute impairment, e.g. due to recent brain surgery (early postoperative MRI), were excluded from recruitment, as were patients under legal guardianship. The questionnaire was conducted on Dutch-speaking patients only. Participation was voluntary, and patients did not receive any compensation.

Additional information on sex, age at study participation, tumor type and therapy course were added based on medical records. Grade 4 and 3 lesions were classified as high-grade gliomas (HGG), as most lesions were glioma-type. All others were in the LGG category. The WHO classification at the time of surgery defined the diagnosis. The number of previous MRI scans was registered from electronic hospital notes.

Questionnaire

Originally, the questionnaire contained ten questions plus one open comment space. It was extended by one additional question (question 11) during the course of the study in order to gain additional information on patient knowledge of GBCA.

First, the patient was asked to estimate their total number of tumor-related brain MRIs received until present. This was to evaluate if patients realistically assess the burden of MRI during the disease. The other questions required single-choice categorical and ordinal tick-box answers. Eight out of eleven questions allowed multiple answer options.

Questions 2 and 10 were general questions on the burden of undergoing radiological follow-up as a patient with a primary brain tumor. Questions 3–6 covered the dimension of burden due to GBCA injection. Questions 7–9 covered the burden of the MRI scan procedure beyond GBCA injection. An open comment section ended the questionnaire. These comments were categorized into four groups: general burden of MRI, attitude towards GBCA injection, the burden due to follow-up/scan interval, and others.

The English version of the PENGUIN questionnaire can be found as Online Resource 1.

Analysis

Data was analyzed with descriptive statistics. Subgroup analyses were performed for sex, age, tumor grade, and the number of follow-up scans. Question 10 was transformed to a binary metric during the analysis, as patients were allowed to give multiple answers. If patients left all the boxes empty, they were, after confirmation by the patient, categorized as not having any stress. The subgroup comparison involved parametric testing with the Pearson chi-square test and the Mann–Whitney U-test for categorical and ordinal questions, respectively. We also performed the Pearson correlation test. Bonferroni correction was performed for multiplicity. The significance level was set by dividing the significance threshold (0.05) by the number of subgroups (4) at p < 0.01.

Results

Patient demographics

Of the one hundred filled-in questionnaires, 61 were from male patients (mean age ± standard deviation (SD): 44 ± 14 years) and 39 from female patients (mean age ± SD: 46 ± 13 years, Table 1). The age difference was insignificant between male and female patients (p = 0.4). Ninety-three patients had a histopathologically confirmed diagnosis. The other seven patients were considered to have a slow-growing low-grade lesion based on their radiophenotype and growth rates. In total, 41 patients had a HGG. Online Resource 2 shows the number of patients for each tumor entity.

General burden of MRI

Patients systematically underestimated the number of scans they had undergone (49 underestimations vs 39 overestimations). An increase in the number of follow-up scans was associated with an increased underestimation of MRI burden (Fig. 1). If overestimation occurred, it was more marked than in cases of underestimation: 5 + 6.57 scans overestimated compared to 3 + 4 scans (median + interquartile range) underestimated, respectively. There was no significant difference in over- or underestimation between men and women (p = 0.83).

Percentage of patients overestimating, underestimating, or guessing correctly the number of MRI for glioma they had undergone until questionnaire session (y-axis) as sorted by the number of MRI they had truly undergone (x-axis). Underestimation of scan burden increases with the number of MRI undergone

The general trend was that patients did not consider MRI scans burdensome, as shown in Fig. 2. It appeared that older patients experienced lying in the MRI as longer than younger patients, albeit not significantly (Q9, Online Resource 3). The most frequent stress factor was fear of outcome/bad news (Fig. 2). Five patients found the noise annoying or suggested extra hearing protection beyond the existing double layer.

Women reported more symptoms during or directly after the MRI (Q7) and found it more annoying than males (Q8). Women also experienced more stress from fearing bad news (Q10.1) and the travel times to the MRI unit (Q10.2) and experienced more stress in general (Q10.6). Patients with less than ten previous MRIs were significantly more dissatisfied regarding the scan follow-up interval than patients with 30 or more scans. The same group (< 10 scans) showed significantly less fear towards receiving an intravenous (IV) cannula. Finally, LGG patients experienced more claustrophobia than HGG (Online Resource 3).

Attitude towards GBCA injection

Most patients did not experience GBCA injections as burdensome (Fig. 3). However, 40% described at least some irritation when receiving IV administration. 63% preferred an MRI scan without GBCA if considered diagnostically equivalent. Fifty-eight patients answered the additional question about possible adverse effects from GBCA, but only three patients were aware of these. Nearly all patients found the wait between placing the cannula and taking the MRI perfect or short. Several patients wrote that they found cannulas annoying and painful and would prefer no cannula if diagnostic performance was maintained. One patient also mentioned that patients should receive more information regarding the use of GBCA agents.

Female patients found cannula placement significantly more unpleasant than males (Q4). There were no significant differences between males and females regarding preferences for MRI options without GBCA (Q5).

Discussion

Patients with primary brain tumors expressed a generally positive attitude towards the current neuro-oncological MRI follow-up scheme in this monocentric survey at a tertiary academic center. However, GBCA-free MRI protocols would be preferred, provided their diagnostic non-inferiority. Importantly, patient knowledge about any potential adverse effects of GBCA was rare, and we identified women as less satisfied. At the same time, age, diagnosis and number of previous scans had no impact on satisfaction.

Patients underestimated the number of scans they had undergone, with underestimation being positively correlated with the number of previous scans. Scan burden underestimation can be explained by ‘positivity bias in memory’—a phenomenon describing a person’s inclination to remember pleasant events more vividly and favorably than unpleasant ones [31, 32]. Patients with 30 scans or more were significantly more satisfied with the number of scan follow-ups than patients with ten scans or fewer. We hypothesize that patients with more scans are more likely to think they are in a stable phase of their disease than patients who only recently got diagnosed. There is a tendency in the medical community to reduce both MRI frequency and protocol duration, scan time. Arguments are costs, waiting lists, and the assumption that patients find the MRI uncomfortable and have difficulty complying [33,34,35]. However, our results showed that most patients did not experience MRI as burdensome and that the follow-up intervals are perceived as appropriate—even by frequently scanned glioblastoma patients. The debate about whether scan frequency and protocol duration need to be reduced should include the patients, as they might oppose longer control intervals. On the other hand, data implies that most patients will tolerate moderate scan duration extension for imaging research.

However, certain patients experienced at least moderate discomfort during the MRI scan. It is worthwhile to study this group in more detail.

Our most remarkable and also most consistent finding is the role of sex in the perception of MRI. Overall, women found the MRI procedure more uncomfortable than men, which was characterized by experiencing the MRI procedure as more unpleasant, more often being afraid of bad news, and having a tendency to be more stressed about the travel times. These findings align with literature suggesting that women experience more stress and anxiety also when confronted with a brain tumor diagnosis [36, 37]. Women also found receiving a cannula more unpleasant. Research has reported that sex is a risk factor for difficult venous access and that catheter insertion in women is more difficult, explaining the difference in comfort [38]. We conclude that sex, and most likely gender, is not sufficiently reflected in the current MRI workflow of brain tumor patients despite indicators for relevant differences between male and female perception. According to our results, women will benefit from shorter MRI protocols–and should innovation permit it–even GBCA-free ones. The discussion between patient welfare and patient clinical needs should therefore be carefully balanced.

The age, number of previous scans, and diagnosis had surprisingly little impact on patients’ MRI perception. Increasing age is a known stress factor for patients and MRI technicians [39]. In our study, we could only confirm a tendency below the significance threshold regarding age: older patients tended to experience the MRI scan as longer and less comfortable than younger patients. This is relevant as brain tumor MRI protocols are particularly lengthy.

Patients with ten or fewer scans showed less fear of receiving a cannula than patients with 30 scans or more, at a significant level before and a possibly still relevant level after Bonferroni correction. While the probability of a negative experience with cannulas increases with the growing number of scans, this contrasts with what would be expected as dictated by exposure therapy. With exposure therapy, frequent engagement with anxiety-provoking stimuli, such as cannulas, can reduce and disconfirm a person’s fearful projections towards the respective stimulus [40, 41].

Patients with a low-grade lesion experienced more claustrophobia than patients with a high-grade lesion. Patients in the low-grade group had a mean age of 41 years, while patients in the high-grade group had a mean age of 49, as expected. Even though the age differences between the two groups were normally distributed, the age difference could explain this finding as younger patients tend to be more stressed [42]. As younger patients with low-grade lesions will likely receive more follow-ups during their life time, any scientific innovation towards shorter protocols will be particularly in their favor. Clinically, the time between scans, the number of included sequences, and the decision of administering contrast is generally based on the lesion type. However, our results show that tumor type, a reflection of disease severity, does not play a relevant role in the perception of MRI. While our research did not focus on the patient-disease relationship, there may be a link between the patients’ tolerance for number of follow-up scans and scan duration and the type of disease.

An estimated ~ 40% of all MRI scans in neuroradiology are GBCA-dependent [43]. Therefore, patient opinion on gadolinium should be considered with the aim of shared decision-making [44]. Our results show that most patients would opt for an MRI scan without GBCAs if considered diagnostically non-inferior, supporting research in that direction. However, patients showed a profound lack of knowledge of GBCAs, including insufficient knowledge regarding possible adverse effects despite being a frequently prescribed diagnostic agent. Patients seemed to be poorly informed and could thus not make optimal decisions about their welfare. At this point, it must be understood that patients in the Netherlands will usually never meet with a radiologist, nor is written informed consent for MRI examinations with GBCA mandatory. Potential contraindications for MRI are ruled out by the clinician ordering the MRI scan. A detailed procedure description for the patient is usually not part of this conversation. Especially considering that pharmaco-safety agencies urge clinicians to reduce the use of gadolinium in the clinical workflow of glioma patients [16, 45], patients should be well-informed about the added value of GBCAs and their possible harm to the human body [13]. Beyond considerate use of GBCA and conciseness of scan protocols, there are other factors which may be relevant to increase patient comfort such as an acoustic optimization of sequences, as was confirmed by the comments of five of our participants [46].

There are several limitations to this study. First, this is a monocentric study with Dutch patients only, with consequences for data interpretation. The sample was, however, representative of the disease's general prevalence regarding diagnosis, age, and sex distribution [47]. Second, some of our patients have outdated diagnosis without an IDH classification which may result in high grade glioma patients being considered low grade glioma. Patients for whom the questionnaire was too much of a burden were excluded, as were non-Dutch-speaking patients due to the language barrier. This biases the study, potentially underestimating the MRI burden by excluding the sickest patients and patients with a different cultural background. Further, the reference number of MRI scans derived from hospital records is a minimum estimate. Patients could also have been scanned elsewhere. However, patients in the Netherlands usually adhere to one clinic only for treatment and follow-up—making a relevant deviation in the correct total number of scans unlikely.

In summary, this study finds that patients with primary brain tumors generally have positive experiences with neuro-oncological MRI. Especially women, however, would support endeavors towards GBCA-free MRI diagnostics and shorter protocols. Approaches to reduce imaging frequency are neither a patient priority, nor preference. A lack of knowledge on GBCA indicates that shared decision-making remains an unreached goal in glioma imaging.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CET1w:

-

Contrast-enhanced T1 weighted imaging

- DSC:

-

Dynamic susceptibility contrast

- EORTC:

-

European organization for research and treatment of cancer

- GBCA:

-

Gadolinium-based contrast agent

- HGG:

-

High-grade glioma

- IV:

-

Intravenous

- LGG:

-

Low-grade glioma

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- WHO:

-

World health organization

References

Cheung YY, Goodman EM, Osunkoya TO (2016) No more waits and delays: streamlining workflow to decrease patient time of stay for image-guided musculoskeletal procedures. Radiographics 36:856–871. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2016150174

Beker K, Garces-Descovich A, Mangosing J et al (2017) Optimizing MRI logistics: prospective analysis of performance, efficiency, and patient throughput. AJR Am J Roentgenol 209:836–844. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.16.17698

Recht MP, Block KT, Chandarana H et al (2019) Optimization of MRI turnaround times through the use of dockable tables and innovative architectural design strategies. AJR Am J Roentgenol 212:855–858. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.18.20459

Smith-Bindman R, Kwan ML, Marlow EC et al (2019) Trends in use of medical imaging in US health care systems and in Ontario, Canada, 2000–2016. JAMA 322:843–856. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.11456

Tyldesley-Marshall N, Greenfield S, Neilson SJ et al (2021) The role of magnetic resonance images (MRIs) in coping for patients with brain tumours and their parents: a qualitative study. BMC Cancer 21:1013. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-08673-z

Ellingson BM, Bendszus M, Boxerman J et al (2015) Consensus recommendations for a standardized Brain tumor imaging protocol in clinical trials. Neuro Oncol 17:1188–1198. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nov095

Weller M, van den Bent M, Preusser M et al (2020) EANO guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of diffuse gliomas of adulthood. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 18:170–186. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-020-00447-z

Gui C, Lau JC, Kosteniuk SE et al (2019) Radiology reporting of low-grade glioma growth underestimates tumor expansion. Acta Neurochir 161:569–576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-018-03783-3

Jooma R, Waqas M, Khan I (2019) Diffuse low-grade glioma - changing concepts in diagnosis and management: a review. Asian J Neurosurg 14:356–363. https://doi.org/10.4103/ajns.AJNS_24_18

Gui C, Kosteniuk SE, Lau JC, Megyesi JF (2018) Tumor growth dynamics in serially-imaged low-grade glioma patients. J Neurooncol 139:167–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-018-2857-x

Monroe CL, Travers S, Woldu HG, Litofsky NS (2020) Does surveillance-detected disease progression yield superior patient outcomes in high-grade glioma? World Neurosurg 135:e410–e417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.12.001

Ji SY, Lee J, Lee JH et al (2021) Radiological assessment schedule for high-grade glioma patients during the surveillance period using parametric modeling. Neuro Oncol 23:837–847. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noaa250

Mallio CA, Quattrocchi CC, Rovira À, Parizel PM (2020) Gadolinium deposition safety: seeking the patient’s perspective. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 41:944–946. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A6586

Parillo M, Sapienza M, Arpaia F et al (2019) A structured survey on adverse events occurring within 24 hours after intravenous exposure to gadodiamide or gadoterate meglumine: a controlled prospective comparison study. Invest Radiol 54:191. https://doi.org/10.1097/RLI.0000000000000528

(2017) Gadolinium-containing contrast agents. In: European Medicines Agency. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/referrals/gadolinium-containing-contrast-agents

(2018) FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns that gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs) are retained in the body; requires new class warnings. In: FDA. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-warns-gadolinium-based-contrast-agents-gbcas-are-retained-body

McDonald RJ, Levine D, Weinreb J et al (2018) Gadolinium retention: a research roadmap from the 2018 NIH/ACR/RSNA workshop on gadolinium chelates. Radiology 289:517–534. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2018181151

Lehmann P, Monet P, de Marco G et al (2010) A comparative study of perfusion measurement in brain tumours at 3 Tesla MR: arterial spin labeling versus dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced MRI. Eur Neurol 64:21–26. https://doi.org/10.1159/000311520

Warmuth C, Gunther M, Zimmer C (2003) Quantification of blood flow in brain tumors: comparison of arterial spin labeling and dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology 228:523–532. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2282020409

Mehrabian H, Desmond KL, Soliman H et al (2017) Differentiation between radiation necrosis and tumor progression using chemical exchange saturation transfer. Clin Cancer Res 23:3667–3675. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2265

Zhou J, Tryggestad E, Wen Z et al (2011) Differentiation between glioma and radiation necrosis using molecular magnetic resonance imaging of endogenous proteins and peptides. Nat Med 17:130–134. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.2268

Togao O, Hiwatashi A, Yamashita K et al (2017) Grading diffuse gliomas without intense contrast enhancement by amide proton transfer MR imaging: comparisons with diffusion- and perfusion-weighted imaging. Eur Radiol 27:578–588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-016-4328-0

Patel M, Zhan J, Natarajan K et al (2021) Machine learning-based radiomic evaluation of treatment response prediction in glioblastoma. Clin Radiol 76:628.e17-628.e27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2021.03.019

Jayachandran Preetha C, Meredig H, Brugnara G et al (2021) Deep-learning-based synthesis of post-contrast T1-weighted MRI for tumour response assessment in neuro-oncology: a multicentre, retrospective cohort study. Lancet Digit Health 3:e784–e794. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(21)00205-3

Morana G, Tortora D, Staglianò S et al (2018) Pediatric astrocytic tumor grading: comparison between arterial spin labeling and dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI perfusion. Neuroradiology 60:437–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-018-1992-6

Novak J, Withey SB, Lateef S et al (2019) A comparison of pseudo-continuous arterial spin labelling and dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI with and without contrast agent leakage correction in paediatric brain tumours. Br J Radiol 92:20170872. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20170872

Vidyasagar R, Abernethy L, Pizer B et al (2016) Quantitative measurement of blood flow in paediatric brain tumours-a comparative study of dynamic susceptibility contrast and multi time-point arterial spin labelled MRI. Br J Radiol 89:20150624. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20150624

Corell A, Guo A, Vecchio TG et al (2021) Shared decision-making in neurosurgery: a scoping review. Acta Neurochir 163:2371–2382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-021-04867-3

Robin AM, Kalkanis SN, Rock J et al (2014) Through the patient’s eyes: an emphasis on patient-centered values in operative decision making in the management of malignant glioma. J Neurooncol 119:473–479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-014-1492-4

Terwee CB, Prinsen CA, de Vet HCW et al (2018) COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: a Delphi study. Qual Life Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1829-0

Sedikides C, Green JD (2009) Memory as a self-protective mechanism. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 3:1055–1068. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00220.x

Adler O, Pansky A (2020) A “rosy view” of the past: Positive memory biases. In: Aue T, Okon-Singer H (eds) Cognitive Biases in Health and Psychiatric Disorders. Academic Press, Cambridge, pp 139–171

Sartoretti E, Sartoretti T, Binkert C et al (2019) Reduction of procedure times in routine clinical practice with Compressed SENSE magnetic resonance imaging technique. PLoS One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214887

Hollingsworth KG (2015) Reducing acquisition time in clinical MRI by data undersampling and compressed sensing reconstruction. Phys Med Biol 60:R297-322. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/60/21/R297

Mekle R, Wu EX, Meckel S et al (2006) Combo acquisitions: balancing scan time reduction and image quality. Magn Reson Med 55:1093–1105. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.20882

Remes O, Brayne C, van der Linde R, Lafortune L (2016) A systematic review of reviews on the prevalence of anxiety disorders in adult populations. Brain Behav. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.497

Braun SE, Willis KD, Mladen SN et al (2022) Introducing FCR6-Brain: Measuring fear of cancer recurrence in brain tumor patients and their caregivers. Neurooncol Pract 9:509–519. https://doi.org/10.1093/nop/npac043

Jacobson AF, Winslow EH (2005) Variables influencing intravenous catheter insertion difficulty and failure: an analysis of 339 intravenous catheter insertions. Heart Lung 34:345–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2005.04.002

Osmanovic-Thunström A, Mossello E, Åkerstedt T et al (2015) Do levels of perceived stress increase with increasing age after age 65? A population-based study. Age Ageing 44:828–834. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afv078

Abramowitz JS, Deacon BJ, Whiteside SPH (2019) Exposure Therapy for Anxiety, Second Edition: Principles and Practice. Guilford Publications

Joseph JS, Gray MJ (2008) Exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. The J Behav Anal Offender Vict Treat Prev 1:69–79. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0100457

Donnellan MB, Lucas RE (2008) Age differences in the big five across the life span: evidence from two national samples. Psychol Aging 23:558–566. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012897

(2022) Guideline Safe Use of Contrast Media Part 3. Radiological Society of The Netherlands

Shared decision making. In: NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/personalisedcare/shared-decision-making/

Runge VM (2017) Critical questions regarding gadolinium deposition in the brain and body after injections of the gadolinium-based contrast agents, safety, and clinical recommendations in consideration of the EMA’s pharmacovigilance and risk assessment committee recommendation for suspension of the marketing authorizations for 4 linear agents. Invest Radiol 52:317–323. https://doi.org/10.1097/RLI.0000000000000374

Oztek MA, Brunnquell CL, Hoff MN et al (2020) Practical considerations for radiologists in implementing a patient-friendly MRI experience. Top Magn Reson Imaging 29:181–186. https://doi.org/10.1097/RMR.0000000000000247

Lin Z, Yang R, Li K et al (2020) Establishment of age group classification for risk stratification in glioma patients. BMC Neurol 20:310. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-020-01888-w

Acknowledgements

The authors do not have any acknowledgements.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by IJHGW, HLH, and VCK. The first draft of the manuscript was written by IJHGW and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Amsterdam University Medical Center, location VUmc Ethics Committee (Date 26–08-2021/No 2021.0384).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wamelink, I.J.H.G., Hempel, H.L., van de Giessen, E. et al. The patients’ experience of neuroimaging of primary brain tumors: a cross-sectional survey study. J Neurooncol 162, 307–315 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-023-04290-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-023-04290-x