Abstract

Phonological assimilation phenomena are often restricted by morphological boundaries. This paper presents data from Mgira in order to argue that both root boundaries and affix boundaries serve to block assimilation processes such as nasal place assimilation and postnasal voicing. The result is that assimilation may obtain, but only within morphemes, not across them. This is analysed as confirmation of the power of the CrispEdge constraints proposed by Itô and Mester (1999) to take precedence over general markedness constraints, blocking feature spreading across morphological boundaries. The analysis is claimed to yield the same effect as a Morpheme Structure Constraint, limiting the force of a constraint to within the boundaries of morphemes.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A core component of any theory of assimilation is the domain of application. This is particularly true when phonological processes are sensitive to morphological structure. One way that phonological theory deals with domains is in an “outward” fashion, where the cyclic application of rules or evaluation of constraints reflects the internal morphological structure of the word, beginning with roots, and proceeding to outer morphological structures like affixes (Mascaró 1976; Kiparsky 1982, 1993, 2000). In constraint-based models, a core component of the theory of faithfulness includes a set of constraints delimited by position, i.e. those which fall under the category of “positional faithfulness” (Beckman 1997, 1998). This includes faithfulness to prosodic categories/edges, but also morphological ones, including roots. What is fundamental to this approach is the idea that faithfulness holds more stringently over smaller, more internal domains (Mohanan 1993), or that the domains to which constraints/processes apply can ratchet up in terms of size (Suzuki 1998; see also Odden 1994).

In addition to the morphologically inward direction in which faithfulness constraints apply, approaches to positional faithfulness (Beckman 1997, 1998; cf. Steriade 1995) have established a set of observations, such that:

-

(1)

There are languages with more segmental contrasts and/or consonant clusters in roots than in affixes.

-

(2)

There are no languages with more segmental contrasts and/or consonant clusters in affixes than in roots.

These generalisations are captured in positional faithfulness theory by resorting to a meta-ranking root-faith » affix-faith (McCarthy and Prince 1995, 1999), or by positing only root-faith (and no affix-faith) (Beckman 1997, 1998) and by not allowing *root/F types of markedness constraints.

This article aims to present an additional generalisation:

-

(3)

There are some languages with more types of consonant clusters across morpheme boundaries than in roots.

It will be demonstrated that Mgira exhibits the pattern in (3), where the failure for assimilation to apply across a morpheme boundary yields a larger set of clusters across boundaries than within morphemes. This pattern is strikingly different from other well-known cases of processes applying across morpheme boundaries, but not inside of roots, such as nasal substitution in Indonesian (Pater 1999, 2001). The more precise claim is that the phonological processes of nasal place assimilation (NPA) and postnasal voicing (PNV) in Mgira exhibit rigid adherence to not only inner (i.e. root) domains, but to all morphological domains. In other words, voicing and place agreement processes in nasal-obstruent sequences apply nearly without exception within the boundaries of a morpheme, but are blocked when they would apply across boundaries. Thus, NPA and PNV in Mgira do not hold more stringently over internal domains (in terms of the morphological structure of the word), but instead, hold over each atomic domain itself. Thus, NPA and PNV in Mgira resemble a Morpheme Structure Constraint.

The solution to the problem that (3) raises for modelling assimilation is to treat domains by reference to their boundaries. This is the spirit of theories such as Generalized Alignment (McCarthy and Prince 1993; Itô and Mester 1999). This approach does not adopt a necessarily “outward” application of processes, as various domain boundaries can be relevant to the grammar, depending on the ranking of alignment constraints. This will be modelled in terms of Crisp Edge effects (Itô and Mester 1999), where the content of edge-preserving constraints prohibits phonological material from extending across edges. This work broadens the analysis of assimilatory spreading blocked by boundaries initiated by Noske (1997) and demonstrates that all boundaries in Mgira block this type of spreading. The challenge in theoretical terms is in accounting for (3) while not losing an analysis of (1)–(2). The proposal is that CrispEdge constraints allow for (3), while not subverting the effects that yield (1)–(2). The alternative, invoking a highly ranking constraint on affix identity (affix-ident[F]) to account for the Mgira facts, would contradict (2), and it would preclude affix-internal NPA/PNV. The analysis allows for a way for affix (or non-root) environments to appear to sustain more consonant clusters than roots. However, a prediction is that this will always be due to the effect of CrispEdge constraints. The result is that there is no need for constraints to explicitly reference “affix” as a category.

This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents data from Mgira and draws generalizations about the behaviour of nasal-obstruent clusters morpheme-internally and across morpheme boundaries. Sect. 3 offers an analysis of assimilation in Mgira as evidence of CrispEdge constraints blocking phonological processes across morpheme boundaries and draws the equivalence between the current analysis and that of a Morpheme Structure Constraint. Sect. 4 lays out competing analyses. Sect. 5 concludes.

2 Mgira nasals

Mgira is an Oceanic language spoken on the island of Epi in Vanuatu.Footnote 1 The focus of this section is on sequences of nasals followed by obstruents in the language. Mgira exhibits a three-way place contrast between the nasals /m/, /n/, and /ŋ/. In addition, there is a contrast in voicing among the obstruents: /p/, /t/, /k/, and /f/ vs. /b/, /d/, /g/, and /v/. The full consonant inventory is given in (4):

-

(4)

For reference, Mgira syllable structure is briefly outlined here. Onsets are optional, and complex onsets are permitted. Setting aside clusters involving nasals (as it is unclear what their syllable affiliation is), this is illustrated with [fra.ga.na] ‘food.’ The data suggests that non-nasal onset clusters are limited to two consonants. Syllable codas are also tolerated in the language as in [ap.kei] ‘what,’ [ma.lum] ‘soft,’ though at present there is no unambiguous evidence for coda clusters. This yields the following syllable types: CV, V, VC, CVC, CCV, CCVC. The nasals in the language can (by hypothesis) be syllabified as an onset with a following less sonorous segment (e.g. [mbaŋə] ‘to eat’); however, these sequences are not likely analysable as prenasalised stops, as (a) the nasals can be syllabified separately from a following consonant in VC.CV sequences, e.g. in informal pause-break types of tasks (Derwing 1992), (b) many of the forms can be separated morphologically, (c) nasals can cluster with other nasals and with sonorants (e.g. [n-man] ‘the bird’), (d) #NC clusters need not be homorganic, (e) to our knowledge, word final NC# and word-internal VNC.CC do not occur. As Henton et al. (1992) and Maddieson and Ladefoged (1993) claim, no language contrasts prenasalised stops with sequences of a nasal and a stop. It should be noted, though, that even if these sequences were prenasalised, it would not affect the analysis. The fact that sometimes there is agreement in place of articulation and voicing in word-initial position, and sometimes not, is enough to warrant the approach outlined below. Finally, as far as we are aware, there are no other cases of place assimilation or voicing assimilation in the language outside of the contexts to be described here.

2.1 Nasal-obstruent clusters root-internally

Nasal-obstruent clusters in Mgira behave differently depending on their position in the word. Heterorganic nasal-obstruent clusters, or clusters with voiceless consonants, are disallowed and never surface within the root. That is, within roots, clusters must agree in voicing and place of articulation. The only acceptable nasal clusters root-internally include the homorganic [nd], [mb], and [ŋg].Footnote 2 Examples of these clusters are provided in (5).

-

(5)

What is evident is that there is a markedness restriction which holds stringently within roots. This in itself is not unexpected, as both NPA and PNV are common processes cross-linguistically (Pater 1999, 2001). All other things being equal, the pattern so far requires little more than ranking constraints on agreement (Agree[place] and Agree[voice]) above the relevant faithfulness constraints (Ident[place] and Ident[voice], respectively). However, we turn next to contexts across morpheme boundaries, a pattern which makes the root-internal assimilation appear problematic.

2.2 Nasal-obstruent clusters across morpheme boundaries

Marked nasal-obstruent clusters are allowed in Mgira when they occur across morpheme boundaries. The clearest example of this is found with the realis prefix m-, which attaches to the left edge of the root in adjectives, verbs, and adverbs (Tryon 1996). A selection of realis (with the prefix) and irrealis (bare root) forms for semi-regular Mgira verbs is presented in (6).

-

(6)

When the prefix m- attaches to a root form in Mgira, the resulting nasal-obstruent clusters surface as marked sequences, often disagreeing in both voice and place of articulation, due to the fact that neither the nasal nor the following obstruent alternate. The examples in (7) reflect attested nasal-obstruent clusters across morpheme boundaries with this prefix:Footnote 3

-

(7)

These cases indicate that there is no independent pressure forcing the prefix nasal to surface as some contextually unmarked variant, because it is consistently surfacing as labial, and not as coronal (the presumed unmarked place). The same can be said for any of the voiceless obstruents which follow the nasal.

The tolerance for marked clusters also holds across other morpheme boundaries in the language, such as reduplication and suffixation, as seen in the examples in (8), (9), and (10):Footnote 4

-

(8)

-

(9)

-

(10)

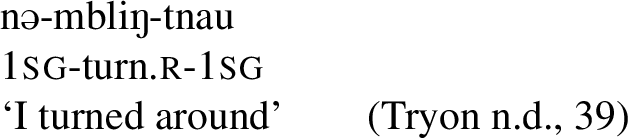

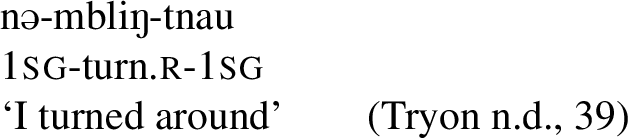

In addition, the nominal prefix n− also exhibits the same behaviour as the realis prefix, preserving place of articulation for the nasal, only this time consistently coronal, as seen in the examples in (11):

-

(11)

It could be argued that since this is a nasal-only morpheme, there is a pressure to ensure that there is a consistent exponent across the paradigm. This, however, is not a uniform pressure found in languages. For instance, nasal-only prefixes are susceptible to NPA and PNV in languages such as Yoruba and Zoque (Pulleyblank 1997). Furthermore, this would not account for other cases of affixes in Mgira which are larger than a single consonant. One such case is the classifying prefix kəm-, which has semantics associated with meteorological phenomena. This prefix consistently surfaces as [kəm-] regardless of the place of articulation of a following consonant, as seen in the examples in (12):

-

(12)

Thus, the behaviour of nasals which form clusters over a morpheme boundary appears to be uniform, and this stands in contrast to the behaviour of the nasals within roots, which undergo NPA and trigger PNV.Footnote 5 This potentially could stand as a challenge to the idea that faithfulness holds more strictly of roots than of affixes, normally encapsulated in the meta-ranking root-faith » affix-faith (McCarthy and Prince 1995, 1999). Reversing this ranking would have severe consequences for the theory of positional faithfulness, as it would predict a range of structures cross-linguistically to be available to affixes and not to roots. The next section, however, presents data which will indicate this is only part of the story for affixes, where they actually pattern much more like roots with regard to assimilation.

2.3 Nasal-obstruent clusters within affixes

While NPA and PNV are blocked across affix-root boundaries in Mgira, there is plenty of evidence to suggest that NPA holds within affixes, exactly as it does within roots. This is illustrated in examples for classifier prefixes (13)–(15), possessive prefixes (16), pronominal suffixes (17), aspectual suffixes (18), and locative suffixes (19).

-

(13)

-

(14)

-

(15)

-

(16)

-

(17)

-

(18)

-

(19)

One possibility is that the behaviour of nasals is due to environmental shielding (Herbert 1986; Stanton 2018), a process whereby nasals surface as prenasalised stops in order to preserve the contrast between nasal and oral segments in environments where the contrast may otherwise be threatened by coarticulation (e.g. a nasal with an adjacent oral vowel).Footnote 6 The behaviour of the nasals in Mgira does not appear to be motivated by environmental shielding, though, as it can be demonstrated that a full range of nasal contrasts exists in each position: word-initially (marou ‘coconut’), intervocalically (momo ‘wet’), pre-/post-consonantally (kəm-lan ‘dawn,’ -təkma ‘to step on something’), and word-finally (kam ‘fire’). As shielding does not occur in these examples, the Mgira data is not compatible with this approach. In addition, there is no contrast between oral and nasalised vowels in the language, casting further doubt on a shielding analysis.

To our knowledge, there are no morphemes which contain within their boundaries a nasal-obstruent sequence which disagrees in place of articulation or in voicing. While not in any way an exhaustive list, this includes the representative sample of roots listed in (5), plus the seven types of affixes which exhibit agreement, out of roughly 500 morphemes from Tryon (n.d.) and our fieldnotes. Given this range of data, it is not simply the case that NPA and PNV hold within roots; they appear to hold within all morphemes. It is only across morpheme boundaries in which these processes are blocked. These boundaries appear to be associated with both inflectional and derivational affixes, both prefixes and suffixes. This renders NPA and PNV static patterns. That is, they are not active processes in the language, a point which will be discussed at the end of Sect. 3. The next section proposes a formalism for encoding these boundaries as assimilation blockers.

3 Assimilation blocking as edge crispness

The patterns in the preceding section strongly indicate that NPA and PNV in Mgira are phenomena which are bound to the domain of the morpheme, including both roots and affixes. Put another way, NPA and PNV hold within morphemes, but not across morpheme boundaries. An analysis of assimilation morpheme-internally, with blocking at boundaries, is sketched in this section.

The assumption adopted here is that the types of assimilation that are under scrutiny can be characterized under a classical feature spreading analysis (Clements 1985; Hayes 1986).Footnote 7 Representations of NPA and PNV as feature spreading are given in (20).

-

(20)

Essentially, these representations are translated into violations of Agree (“NC sequences must agree in place/voicing”; cf. the Identical Cluster Constraints of Pulleyblank 1997), though this could also easily be the Share[F] constraint in McCarthy (2011), where violations accrue based on adjacent segments not being linked to the same autosegment. For simplicity, Agree is adopted here, though without any theoretical commitment to whether this is superior to Share[F]. It will also be assumed that candidates with an additional occurrence of [place] or [voice] would violate the obligatory contour principle (OCP), as in (20c). For instance, Itô et al. (1995) provide theory-internal arguments for the type of spreading in (20b), as this best satisfies constraints on licensing (where, for example, nasals may not license the presence of [voice] without also linking to an obstruent) and paradigmatic constraints which demand that nasals be voiced.

As highlighted above, the only context in which assimilation processes fail to be triggered is across morpheme boundaries. Since this is not simply a case of faithfulness to a particular morphological or prosodic category, nor a case of “outward” oriented application of assimilation, positional faithfulness offers little light to shed on the problem. Instead, the notion of a domain boundary must be imported into the analysis. Following Itô and Mester (1999), the approach here views this type of blocking as the maintenance of “crisp” edges, where the idea is that all phonological material is contained within a particular boundary. Noske (1997) has demonstrated that the threat of “blurred” edges may not only shape syllabification (as Itô and Mester (1999) suggest), but it may also block feature spreading. In other words, the spreading of a feature across a boundary will make the edge of a category “blurry,” and some languages will prohibit this blurriness, at least across some boundaries. Noske (1997) presents the case of fricative allophony in German, demonstrating that a Prosodic Word boundary for some suffixes will block feature spreading.Footnote 8 In this particular case, the constraints forcing the appearance of [x] in the environment following a back vowel (vs. the elsewhere case of [ç]), which presumably involve the spreading of the feature [+back], are blocked by the Prosodic Word edge. This can be illustrated with the boundaries formed by compounds such as Bio-chemiker [biːoçeːmikʌ] ‘biochemist’ and by the diminutive suffix -chen [aotoçən] ‘car (dim)’ (cf. [aoto] ‘car’), both of which block the spreading of [+back] to a following fricative. This approach is also employed by Walker (2001, 2011) and Kügler (2015) in order to restrict the domain of vowel harmony, by Bickmore and Kula (2015) to model tonal spreading, and by Pater (2001) to model nasal substitution in Indonesian. While Walker (2001) restricts spreading within syllables, Kügler (2015) employs CrispEdge constraints to prevent spreading across phonological phrases.

The Mgira patterns can be conceptualized as a more extreme case of blocking, where not only Prosodic Word boundaries, but also internal prefix and suffix boundaries, block spreading. The contrast with German is apparent in that each morphological boundary, be it prefix or suffix, blocks assimilation. This is predicted by the Crisp Edge approach (and technically, by the larger program of Generalized Alignment; McCarthy and Prince 1993). While Itô and Mester’s (1999) approach was focused on prosodic categories, meant to model facts about syllabification and based on the idea that these types of “alignment” constraints are not specific to categories, this formulation can be converted to include grammatical categories. Since we are dealing with not only roots, but all affixes, we for now leave the constraint undifferentiated (though acknowledge that a prediction is that it indeed can be differentiated). It will be assumed, along with Walker (2001), that each CrispEdge constraint takes two arguments—a particular edge (or category), and a feature which is prevented from making the edge blurry (see also Kaplan (2018), who argues that delimitation of edges is necessary). This is a crucial assumption, and one that will be important for the typological consequences to be discussed below. At the moment, though, there is no evidence of either edge of the morpheme in Mgira being blurry. Thus, each constraint will be read as including both the left and right edges. An informal version of the schema is given below; for the formal mechanics, see Itô and Mester (1999, 208). The formulations are as such:

-

(21)

CrispEdge(Morpheme, [place]): A morpheme has crisp edges with respect to the feature [place]

-

(22)

CrispEdge(Morpheme, [voice]): A morpheme has crisp edges with respect to the feature [voice]

For this particular case, these constraints could be generalized to CrispEdge (Morpheme, [F]), as there are no segmental interactions allowed across boundaries. However, we have left these differentiated for expository purposes. The formulation of CrispEdge in (21)–(22) is such that it ranges over morphemes, and such that each edge is protected, similar to the constraint proposed in McCarthy (2007) in order to account for local vs. long-distance assimilation phenomena in Chumash. In that context, long-distance agreement is not bound by the root, and only the local cases of dissimilation-blocking are. Violations of CrispEdge are illustrated below for both the spreading of place features and the feature [voice] across a boundary (+):

-

(23)

The Crisp Edge effect is demonstrated with tableaux for NPA in (24) and PNV in (25). All that is necessary to derive this effect is for CrispEdge[place] to dominate Agree[place] and CrispEdge[voice] to dominate Agree[voice].

-

(24)

-

(25)

With root-internal sequences, CrispEdge is inert, and so assuming Richness of the Base, any hypothetical underlying sequence of disagreeing nasal+stop clusters will incur violations of Agree, and will thus be forced to surface as agreeing for place and voice, as in (26):

-

(26)

The idea that assimilation is sensitive to crisp edges receives additional support from other languages. For instance, Padgett (1995, 153) reports that nasal place assimilation in Gã is total when it is within morphemes, but partial when across morpheme boundaries. For example, within morphemes nasals fully assimilate to a doubly articulated following stop [ŋm]kpai ‘libation’ while across a morpheme boundary the assimilation results in only a velar stop, [ŋ]-kpai ‘my cheeks.’ This is again not a case of an outward-expanding set of nested domains, but a case where an edge may be respected (or be partially “blurry,” as the case may be). Hall (2010) notes that a type of blocking similar to that in Mgira applies in the Emsland dialect of Low German, such that a nasal will assimilate to a following tautomorphemic dorsal stop, but not to a heteromorphemic stop. In that case, it is suffix boundaries which enforce the blocking; prefix boundaries are allowed to be blurry, exhibiting NPA. Booij (2011) discusses nearly identical cases of morpheme-internal NPA in Dutch, but where NPA is blocked at an affix boundary. Thus, Gã, Standard and Emsland German, and Dutch indicate that Mgira does not constitute an isolated case. It just happens to constitute the most extreme case.

The analysis advanced here makes a set of predictions. For instance, if there is a cluster XY that cannot appear inside a root, but can appear elsewhere, then either: (a) XY appears across a morpheme boundary and is due to a constraint in the CrispEdge family, or (b) X and Y are separate morphemes and are faithful due to a constraint that requires morphemes to have consistent surface phonetic exponents. That is, the only reasons that are expected to be found for clustering differences according to morphological category should be the presence of a boundary (which would block assimilation, creating more clusters), or the need for morphemes to have a consistent and/or overt expression.Footnote 9 The Mgira case demonstrates that all morphological boundaries impose a crispness requirement; what remains to be seen is whether any one of the set of internal morphological boundaries may independently impose the same requirement. The need for a large-scale crosslinguistic study on the clustering properties of morphemes is evident. The case at hand, however, helps demonstrate the predictive power of the theory of edge crispness, as originally laid out by Itô and Mester (1999).

The interaction of Agree and CrispEdge, while normally yielding a dynamic result (in the sense of alternations), in this case yields a static result. A natural analysis of the Mgira patterns is to consider NPA and PNV as Morpheme Structure Constraints (Halle 1959; Stanley 1967). This position would view these operations not as the product of active phonological processes (in the sense of yielding alternations), but instead as a static pattern which holds in the underlying representation for each morpheme in the language. We argue that this class of Morpheme Structure Constraints is in fact reducible to the CrispEdge analysis outlined here. This accounts for the range of data presented above and does not afford Morpheme Structure Constraints any special theoretical status.

In classical approaches to Morpheme Structure Constraints, the case of Mgira would be modelled by resorting to underspecification (Kiparsky 1982). For example, in underlying representations, what appears on the surface as NPA is achieved through leaving all pre-stop nasals underspecified for place features. These features are then filled in by later rules. In Optimality Theory there are no constraints on the shape of underlying forms, and thus no Morpheme Structure Constraints per se (Prince and Smolensky 1993). Furthermore, admitting underspecification as an explanation would allow some random prefixes to have underspecified final nasals, which would be predicted to assimilate in a manner exceptional to the pattern. This mechanism is largely unnecessary in the approach sketched above. Regardless of whether place features are fully specified or not in the underlying representation, the Agree constraints will pick out surface candidates which exhibit NPA and PNV. Ranking Agree sufficiently higher than Ident means that all forms will obey agreement, regardless of their underlying status. The addition of CrispEdge constraints thus ensures that all agreement is bounded by each morpheme. This allows heteromorphemic clusters that arise to disagree, giving the impression of agreement only within morphemes, and faithfulness outside of it. Thus, the constraint-based analysis sketched above does exactly the job that a classic Morpheme Structure Constraint would normally do.Footnote 10

4 Alternatives: Domains and cycles

This section briefly lays out several competing analyses for this pattern, including accounts based in cyclic rule application, positional faithfulness, and domain-bounded markedness.

4.1 Inside-out theories

As a response to the duplication problem presented by the presence of both Morpheme Structure Constraints and phonological rules, Lexical Phonology effectively replaced Morpheme Structure Constraints by positing sets of rules which applied early in the derivation (on the first cycle), and a set of rules which applied cyclically after. Domains in the theory are characterized as packages of rule application. The cyclic application of rules reflected the morphological structure of the word, where mechanisms such as the (revised) Alternation Condition (Kiparsky 1982) and the Strict Cycle Condition (Mascaró 1979) were available for protecting phonological structure from being altered within roots, i.e. non-derived environment blocking (Kiparsky 1993). The idea was that there can be no neutralisation rules on the root cycle, because while these rules could add structure, they are prevented from being structure-changing in nature. As these rules are precisely what are required for assimilation, the net result was the protection of roots from neutralizing processes.

The elegance in models employing cyclic rules is that they successfully model the preservation of root contrasts. The problem with this approach is that in order to model the Mgira patterns, it would need to rely on non-cyclic rules to apply to each morpheme, and then cyclic rules to apply and block assimilation in all of the correct environments. This particular issue will be expanded on in the discussion of positional faithfulness constraints further below.

Some of the same insights are also apparent in constraint-based models, where a core component of the theory of faithfulness includes a set of constraints delimited by position, i.e. those which fall under the category of “positional faithfulness” (Beckman 1997, 1998). This includes faithfulness to prosodic categories/edges, but also morphological ones, including roots. In both of these theories, there is a strong precedent for increased markedness root-internally cross-linguistically. In other words, roots are often considered to exhibit stronger adherence to faithfulness constraints than in other morphemes in the word (Mohanan 1993; McCarthy and Prince 1995, 1999; Beckman 1997; Pater 1999; Urbanczyk 2006). For comparison to the Mgira case, this is exemplified by Puyo Pungo Kichwa, which exhibits postnasal voicing across morpheme boundaries, but not within roots (Pater 1999, 323), cf. roots such as untina ‘to stir the fire’ vs. suffix alternations such as wasi-ta ‘the house,’ wakin-da ‘the others.’ As a result, phonological processes occurring across morpheme boundaries are observed to result in less marked structures in many languages, while more marked sequences are maintained within the root. What is fundamental to this is the idea that faithfulness holds more stringently over smaller, more internal domains (Mohanan 1993). This is accomplished either through amnestying root material from initial cycles in Lexical Phonology, or through the meta-ranking root-faith » affix-faith in Optimality Theory.

These approaches are essentially “inside-out,” as they apply rules/constraints to the root exclusively, then move outward with other rules/constraints. The problem that Mgira raises for these inside-out approaches is inherent in the fact that the restriction is found in all morphemes, not just in roots. As noted above, this intersects with the more traditional conception of the Morpheme Structure Constraint, which could in principle apply to any morpheme in a language (Halle 1959; Stanley 1967; Chomsky and Halle 1968). Cyclic rule-based approaches will fail to block the application of NPA and PNV in affixes (and will overapply to certain boundaries), and likewise, the meta-ranking root-faith » affix-faith will either protect all root contrasts, or protect all morphemes equally (depending on where markedness is ranked with respect to these faithfulness constraints), but cannot correctly model the processes as being bound to the confines of the morpheme. In other words, these approaches fail to capture the fact that assimilation occurs root-internally but is blocked at boundaries: m-dom-kle ‘to be able to.’ The problem with a positional faithfulness account lies in a subset problem: faithfulness to roots must dominate general faithfulness in order to yield root preservation, but since there are no true affix faithfulness constraints (Beckman 1998), there is no mechanism to ensure that NPA and PNV will obtain within affixes (as well as roots). Thus, positional faithfulness theory predicts that a scenario can obtain whereby roots are protected, or otherwise where a process applies across the board, irrespective of morphological structure. In essence, these theories model root-affix asymmetries. In Mgira, however, there are no asymmetries; all morphemes equally adhere to the Morpheme Structure Constraints. A larger problem is that what obtains within Mgira morphemes is not a function of faithfulness, but rather markedness: contrasts are not being preserved, but eliminated in these positions.

Incidentally, Mgira is not an isolated case of morpheme-internal processes. Nash (1980) and Poser (1989) present similar cases of morpheme-internal application of rules. In Diyari and Walpiri, stress assignment is sensitive to morphological structure. To exemplify, stress in Diyari falls on odd syllables, excluding final syllables (e.g. pínadu ‘old man,’ ŋándawàlka ‘to close,’ káṇa-wàra-ŋùndu ‘man + pl + abl’). Poser (1990) notes that given these generalisations, there are some cases where stresses are expected but do not appear (e.g. máda-la-ntu ‘hill + charac + proprietive’), and other cases where otherwise unexpected stresses occur:  ‘man + loc + ident.’ As Nash (1980) and Poser (1990) observe, the stress patterns in Walpiri and Diyari only make sense if stress assignment restarts at each morpheme, creating a foot (if possible), then resetting the stress domain, and applying cyclically with the addition of each morpheme. Thus, the Diyari/Walpiri and Mgira cases require some mechanism for delimiting morpheme boundaries, but not in an inside-out fashion.

‘man + loc + ident.’ As Nash (1980) and Poser (1990) observe, the stress patterns in Walpiri and Diyari only make sense if stress assignment restarts at each morpheme, creating a foot (if possible), then resetting the stress domain, and applying cyclically with the addition of each morpheme. Thus, the Diyari/Walpiri and Mgira cases require some mechanism for delimiting morpheme boundaries, but not in an inside-out fashion.

4.2 Domain-bounded markedness

While positional faithfulness theory proves inadequate for modelling assimilation in Mgira, an alternative would be to consider the patterns as the result of positional markedness. Zoll (1998) and Smith (2002) claim that augmentation (in terms of increased perceptual salience) in prominent positions can be achieved through markedness effects, and that there are thus positional markedness constraints. In this type of analysis, a domain-specific version of the markedness constraint Agree[place] can be entertained, holding only over the root. By ranking Agree[place]-Root and Agree[place]-Affix over Ident[place] and Agree[place], this ensures that assimilation always occurs within the root (or affix), violating faithfulness, while in cases straddling morphemes, faithfulness is retained.

Because it is meant to model cases of augmentation, positional markedness theory is fairly tightly constrained. Smith (2002) places two conditions on these constraints: the prominence condition (such that perceptual salience is enhanced or augmented), and the segmental contrast condition, which states that psycholinguistically strong positions (i.e. those used for word-identification) cannot neutralise contrasts. The Mgira case would fail both of these conditions, as it is not clear that perceptual salience is being enhanced, and it is also evident that neutralisation (in the form of assimilation) is affecting prominent positions, such as word-initial position or in roots. Thus, there are no legitimate positional constraints available to model these patterns. In addition, the theory would require both root and affix markedness in order to yield assimilation in all morphemes (e.g. mbər-mbarei ‘breadfruit tree’). The additional problem is that a domain-bounded markedness approach must import the domain boundaries by force, i.e. by specifying in the definition of a markedness constraint that the restriction must apply within a particular domain. This raises the larger problem that the impermeability of these boundaries, while true for Mgira, will not be uniform in other languages. Thus, the Emsland German case, where only one edge (the suffix boundary) is crisp, cannot be modelled with domain-bounded markedness. The Crisp Edge approach outlined above incorporates the boundaries directly into the substance of the constraints.

4.3 Summary

In sum, many of the alternative analyses of the phenomena in Mgira either fail to capture the fact that it is all morphemes which appear to exhibit NPA and PNV, or they reproduce the same analysis as the Crisp Edge approach by smuggling boundaries into the content of constraints. These approaches will fail in many instances because they are all-or-nothing in terms of both edges. This is incorrect, because many phenomena require reference to only a single edge (Kaplan 2018). It can be argued that it is the cases where only a single edge is at play, as in Emsland German, which argue for the Crisp Edge analysis rather than a domain-based analysis, as the latter predicts that both edges must be in play at any given time in order to properly serve as boundaries to a domain. Thus, taking the typological implications into account makes the Crisp Edge analysis the more convincing one.

5 Conclusion

This article has demonstrated that nasal place assimilation and postnasal voicing in Mgira are bound to the morpheme, and the two processes are blocked by any morpheme boundary. While the generalisation is extremely simple, it crucially provides the empirical evidence for the role that edges play in assimilation phenomena, where it was demonstrated that all morphological edges (and not just those of the Prosodic Word) are relevant. This work thus enriches the empirical base on which generalizations are drawn and also provides a discussion for the theory around how morphological categories must be represented in terms of edge crispness. It also opens up important questions regarding what kinds of morphemes have crisp edges, whether arbitrary morphemes can exhibit these effects, whether the typical positional faithfulness effects can be modelled with CrispEdge constraints, what the relative rankings of CrispEdge constraints yield, and what the overall typology is that is generated.

This approach also makes the prediction that other processes will be limited to domain boundaries in this way. This might include processes which normally span over boundaries, such as vowel harmony or tonal spreading. The analysis correctly models the generalisation in (3), without giving up the generalisations in (1) or (2), repeated here:

-

(1)

There are languages with more segmental contrasts and/or consonant clusters in roots than in affixes.

-

(2)

There are no languages with more segmental contrasts and/or consonant clusters in affixes than in roots.

-

(3)

There are some languages with more types of consonant clusters across morpheme boundaries than in roots.

In this way, the approach realizes the classical conception of the Morpheme Structure Constraint by referencing crisp edges of domains, while at the same time yielding the flexibility to allow for only a single edge to be crisp (or blurry), allowing for a wider range of phenomena than just static Morpheme Structure Constraints.

Notes

The language is also referred to as Mae-Morae, Maii, and as Bieria. It is likely that these labels constitute dialects along a continuum; see Tryon (1986) for an overview of the relationships of the languages of Epi Island. The only overview of the grammar of Mgira is Tryon (n.d.). All data presented here was elicited from a native speaker of Mgira; forms which also appear in Tryon (n.d.) are indicated as such.

The only lexical items we are aware of which exhibit disagreement between the nasal and following consonant include the following. The first form is [mdomkle] ‘to be able to’; however, this form doesn’t participate in the realis/irrealis alternation to be outlined in the next section, so we assume it is prefixed with the realis marker m-, and as Tryon (n.d.) points out, it is composed of the verbal suffix -kle (c.f. mdom-wi). The other forms are [amtu] ‘part of,’ [mtə] ‘accompany’ and [mgundu] ‘many,’ though if the latter two forms are a verbal and a nominal modifier, respectively, these may in fact also be prefixed with the realis marker m-. It is significant that [amtu] exhibits disagreement with respect to place and voicing, indicating that it is either morphologically complex, or a lexical exception.

We follow the Leipzig glossing conventions.

There is only one instance of a nasal-fricative cluster that we are aware of: nə-lum-fo ‘1sg-squeeze(irr)-out’ (Tryon n.d., 36). This sequence occurs across a suffix boundary, and only accidentally agrees in place, and not in voice, indicating that there is no true agreement.

The only case we are aware of with assimilation of a prefix nasal is with a single verb. Tryon (n.d., 47) notes that with third person singular subjects, realis prefix m- assimilates to a following coronal stop with the verb ‘to be’; e.g. *m-dəkə, [n-dəkə]. As this is a high-frequency word, its irregularity is not overly surprising.

Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for raising this possibility.

The approach here crucially relies on feature spreading because of the way that the constraints are defined. If another representation/analysis of assimilation were adopted which does not rely on feature spreading (e.g. Agreement by Correspondence; Rose and Walker 2004), the analytical device would be different. This does not nullify the insights of the current analysis; instead, the absence of interaction across morpheme boundaries would need to be modelled differently. Employing Crisp Edge constraints is one possible implementation of the general analysis of prohibiting interactions across morpheme boundaries.

A third logical possibility involves strict faithfulness to all underlying material (Faith » Markedness), which would model languages with only static patterns, i.e. no alternations. This position would only be tenable under a theory which abandons (or severely restricts) Richness of the Base, such that only inputs that can be determined by actual surface evidence are eligible inputs.

As noted earlier, McCarthy’s (2007) analysis of Chumash paves the way for this type of analysis.

References

Beckman, Jill. 1997. Positional faithfulness, positional neutralisation and Shona vowel harmony. Phonology 14: 1–46.

Beckman, Jill. 1998. Positional faithfulness, PhD diss., University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Bickmore, Lee S., and Nancy C. Kula. 2015. Phrasal phonology in Copperbelt Bemba. Phonology 32: 147–176.

Booij, Geert. 2011. Morpheme structure constraints. In The Blackwell companion to phonology, eds. Marc van Oostendorp, Colin J. Ewen, Elizabeth Hume, and Keren Rice, 2049–2069. Oxford: Blackwell.

Chomsky, Noam, and Morris Halle. 1968. The sound pattern of English. New York: Harper & Row.

Clements, George Nickerson. 1985. The geometry of phonological features. In Phonology yearbook, Vol. 2, 225–252.

Derwing, Bruce L. 1992. A ‘pause-break’ task for eliciting syllable boundary judgments from literate and illiterate speakers: Preliminary results for five diverse languages. Language and Speech 35: 219–235.

Hall, Tracy A. 2010. Nasal place assimilation in Emsland German and its theoretical implications. Zeitschrift für Dialektologie und Linguistik 77: 129–144.

Halle, Morris. 1959. The sound pattern of Russian. Mouton: The Hague.

Hayes, Bruce. 1986. Assimilation as spreading in Toba Batak. Linguistic Inquiry 17: 467–499.

Henton, Caroline, Peter Ladefoged, and Ian Maddieson. 1992. Stops in the world’s languages. Phonetica 49: 65–101.

Herbert, Robert K. 1986. Language universals, markedness theory, and natural phonetic processes. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Itô, Junko, and Armin Mester. 1999. Realignment. In The prosody-morphology interface, eds. René Kager, Harry van der Hulst, and Wim Zonneveld 188–217. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Itô, Junko, Armin Mester, and Jaye Padgett. 1995. Licensing and underspecification in optimality theory. Linguistic Inquiry 26: 571–613.

Kaplan, Aaron. 2018. Asymmetric crisp edge. In Hana-bana: A festschrift for Junko Itô and Armin Mester, eds. Ryan Bennett, Andrew Angeles, Adrian Brasoveanu, Dhyana Buckley, Nick Kalivoda, Shigeto Kawahara, Grant McGuire, and Jaye Padgett. Santa Cruz: Department of Linguistics, UCSC. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4r55j619.

Kiparsky, Paul. 1982. From cyclic to lexical phonology. In The structure of phonological representations, eds. Harry van der Hulst and Norval Smith. Vol. 1, 131–175. Dordrecht: Foris publications.

Kiparsky, Paul. 1993. Blocking in non-derived environments. In Studies in lexical phonology, eds. Sharon Hargus and Ellen Kaisse, 277–313. San Diego: Academic Press.

Kiparsky, Paul. 2000. Opacity and cyclicity. The Linguistic Review 17: 351–365.

Kügler, Frank. 2015. Phonological phrasing and ATR vowel harmony in Akan. Phonology 32: 177–204.

Maddieson, Ian, and Peter Ladefoged. 1993. Phonetics of partially nasal consonants. In Nasals, nasalization, and the velum, eds. Marie K. Huffman and Rena A. Krakow, 251–301. San Diego: Academic Press.

Mascaró, Joan. 1976. Catalan phonology and the phonological cycle, PhD diss., MIT.

McCarthy, John J. 2007. Consonant harmony via correspondence: Evidence from Chumash. In University of Massachusetts occasional papers in linguistics 32: Papers in optimality theory III, eds. Leah Bateman, Michael O’Keefe, Ehren Reilly, and Adam Werle, 297–310. Amherst: GLSA.

McCarthy, John J. 2011. Autosegmental spreading in optimality theory. In Tones and features, eds. John A. Goldsmith, Elizabeth Hume, and W. Leo Wetzels, 195–222. Berlin: de Gruyter.

McCarthy, John J., and Alan Prince. 1993. Generalized alignment. In Yearbook of morphology 1993, eds. Geert Booij and Jaap van Marle, 79–153. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

McCarthy, John J., and Alan Prince. 1995. Faithfulness and reduplicative identity. In Papers in optimality theory, eds. Jill Beckman, Laura Walsh Dickey, and Suzanne Urbanczyk, 249–384. Amherst: GLSA.

McCarthy, John J., and Alan Prince. 1999. Faithfulness and identity in prosodic morphology. In The prosody-morphology interface, eds. René Kager, Harry van der Hulst, and Wim Zonneveld, 218–309. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Merchant, Jason. 1996. Alignment and fricative assimilation in German. Linguistic Inquiry 27: 709–719.

Mohanan, Karuvannur P. 1993. Fields of attraction in phonology. In The last phonological rule: Reflections on constraints and derivations, ed. John A. Goldsmith, 61–116. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Nash, David. 1980. Topics in Warlpiri grammar, PhD diss., MIT.

Noske, Manuela. 1997. Feature spreading as dealignment: The distribution of [ç] and [x] in German. Phonology 14: 221–234.

Odden, David. 1994. Adjacency parameters in phonology. Language 70: 289–330.

Padgett, Jaye. 1995. Partial class behavior and nasal place assimilation. In Proceedings of the Southwestern Optimality Theory workshop, 145–183.

Pater, Joe. 1999. Austronesian nasal substitution and other NC effects. In The prosody–morphology interface, eds. René Kager, Harry van der Hulst, and Wim Zonneveld, 310–343. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pater, Joe. 2001. Austronesian nasal substitution revisited. In Segmental phonology in optimality theory: Constraints and representations, ed. Linda Lombardi, 159–182. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Poser, Bill. 1989. The metrical foot in Diyari. Phonology 6: 117–148.

Prince, Alan S., and Paul Smolensky. 1993 [2004]. Optimality theory: Constraint interaction in generative grammar. Manuscript, Rutgers University. [Published by Blackwell 2004].

Pulleyblank, Douglas. 1997. Optimality theory and features. In Optimality theory: An overview, eds. Diana Archangeli and Terence D. Langendoen, 59–101. Oxford: Blackwell.

Rose, Sharon, and Rachel Walker. 2004. A typology of consonant agreement as correspondence. Language 80: 475–531.

Smith, Jennifer L. 2002. Phonological augmentation in prominent positions. London: Routledge.

Stanley, Richard. 1967. Redundancy rules in phonology. Language 43: 393–436.

Stanton, Juliet. 2018. Environmental shielding is contrast preservation. Phonology 35: 39–78.

Steriade, Donca. 1995. Underspecification and markedness. In The handbook of phonological theory, ed. John A. Goldsmith, 114–174. Oxford: Blackwell.

Suzuki, Keiichiro. 1998. A typological investigation of dissimilation, PhD diss., University of Arizona.

Tryon, Darrell. 1986. Stem-initial consonant alternation in the languages of Epi, Vanuatu: A case of assimilation? In FOCAL II: Papers from the fourth international conference on Austronesian linguistics, eds. Paul Geraghty, Lois Carrington, and S. A. Wurm. Vol. 1, 231–242. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Tryon, Darrell. 1996. Mae-Morae and the languages of Epi (Vanuatu). In Oceanic studies: Proceedings of the first international conference on Oceanic studies, eds. John Lynch and Pat Fa’afo, 305–318. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Tryon, Darrell. n.d. Mae Morae grammar. Unpublished manuscript.

Urbanczyk, Suzanne. 2006. Reduplicative form and the root-affix asymmetry. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 24: 179–240.

Walker, Rachel. 2001. Round licensing, harmony, and bisyllabic triggers in Altaic. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 19: 827–878.

Walker, Rachel. 2011. Vowel patterns in language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zoll, Cheryl. 1998. Positional asymmetries and licensing. ROA-282-0998.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Lisa Murgatroyd for sharing the Mgira language with us. We also wish to thank Chris Golston and Paul de Lacy for commenting on earlier drafts, and we wish to thank the editors and three anonymous reviewers for extensive comments. All errors are our own.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brown, J., Meyer, J. Assimilation and morpheme boundaries in Mgira. Nat Lang Linguist Theory (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-023-09606-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-023-09606-0