Abstract

This paper argues based on data from Uyghur (Turkic) that clausal complementation structures involving a special form of the verb ‘say’ are actually adjunct clauses headed by the verb ‘say’ that merge at two heights: VP or TP. I demonstrate that properties unique to ‘say’ as a main verb extend to ‘say’ in these adjunct clauses. Accusative subjects are a primary focus, where it is shown that the re-analysis of clausal complementation has implications for Case Theory in Uyghur and beyond.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

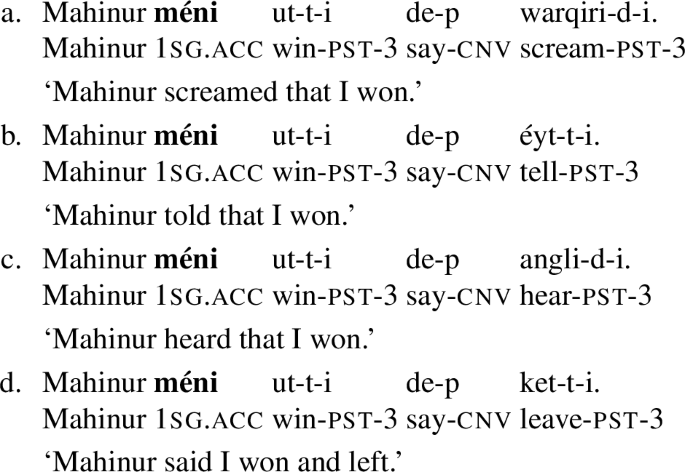

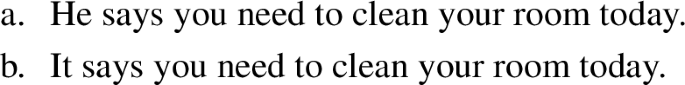

Lord (1976) drew attention to the fact that many languages carry out clausal complementation using some form of the verb ‘say.’ In some studies, these elements have been treated as verbal (Driemel and Kouneli 2020; Kinyalolo 1993; Koopman 1984; Koopman and Sportiche 1989; Özyıldız 2017), but it is far more common for these elements to be treated as simple complementizers (selected by V or N) that are akin to English that. In the present paper, I contribute to this discussion based on data from Uyghur (Southeastern Turkic), such as the cases in (1).Footnote 1

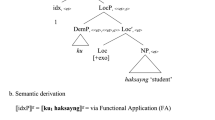

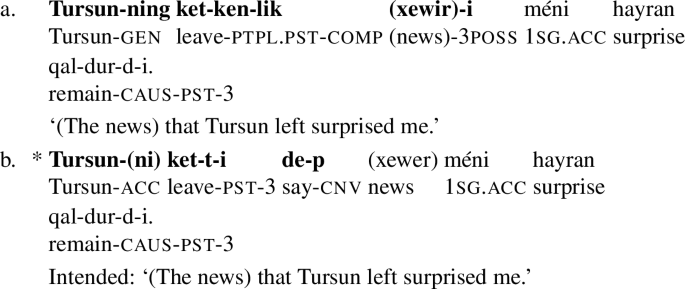

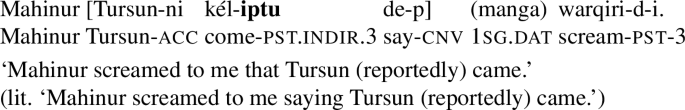

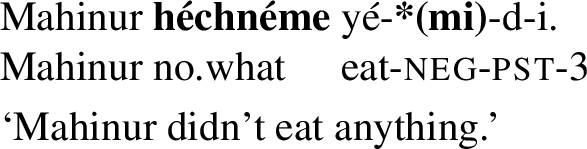

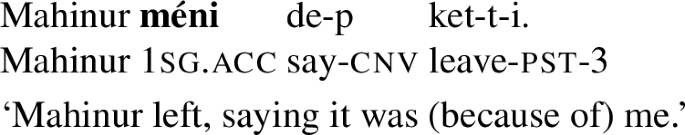

-

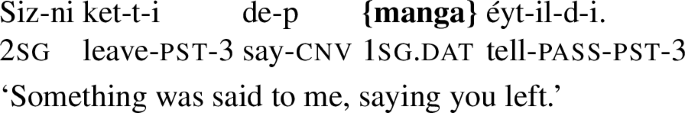

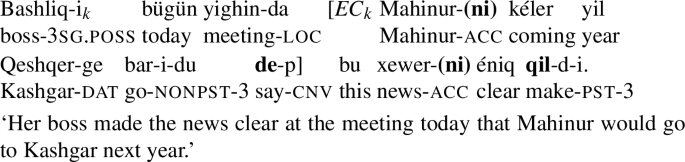

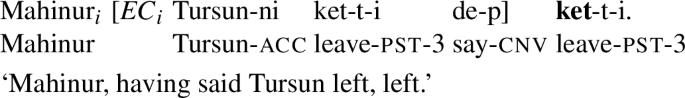

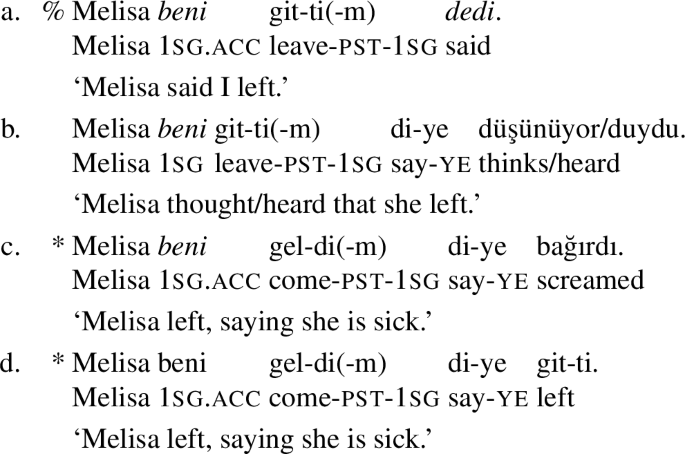

(1)

-

(2)

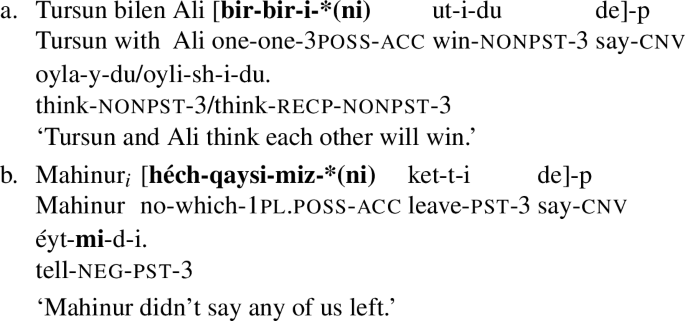

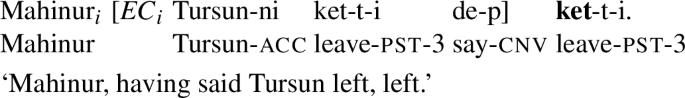

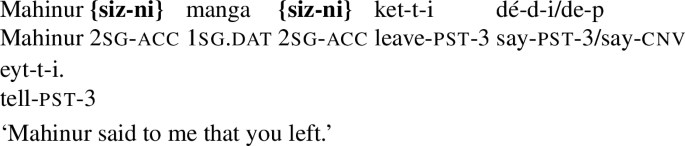

Notice that the bolded portions of (1) and (2) are the same. The present paper argues that rather than this being a diachronic coincidence, the syntactic structure of the bolded regions across these examples is identical; that is, both examples contain the verb ‘say,’ which introduces a tensed clausal complement. Whereas in (1), it is indisputable that de- is the verb ‘say,’ I suggest the same for de- in dep, the apparent “complementizer,” in (2). This analysis predicts that properties unique to ‘say’ in cases like (1) should similarly be observed in de-p (henceforth dep) clauses, which I demonstrate to be the case.Footnote 2

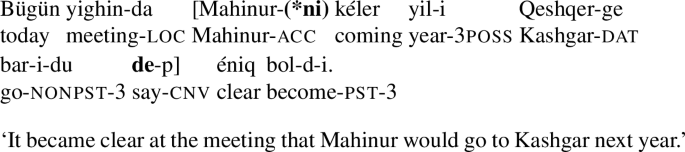

In this paper, I suggest that the grammatical mechanism responsible for linking ‘say’ clauses to the matrix clause is transparently represented in the morphology of dep; namely, the converbial suffix -(I)p, as shown in (3).

-

(3)

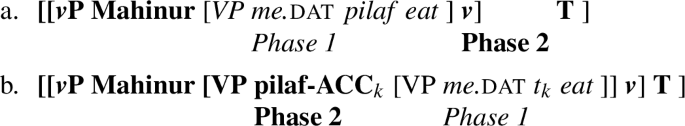

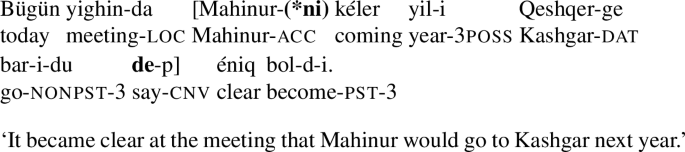

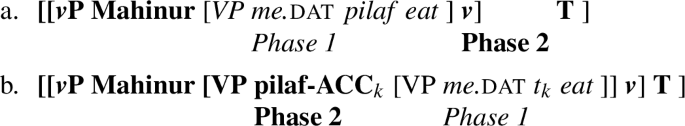

I demonstrate that -(I)p clauses are adjuncts that merge at two distinct heights: TP and VP, as shown in (4).

-

(4)

I argue that it is in precisely these two positions that dep merges into the structure, which gives rise to distinct morpho-syntactic and semantic properties. This analysis is strikingly similar to the analysis of Washo non-factive predicates, which are also treated as modifiers, not arguments (Bochnak et al. 2021). However, unlike Washo, dep clauses not only contain an adverbial linker, but also the verb ‘say.’ In this way, I show that these structures exhibit the external syntax of converbial constructions, but the internal syntax (and semantics) of sentences containing the verb ‘say.’

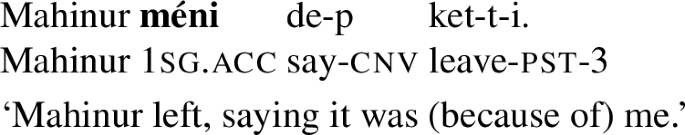

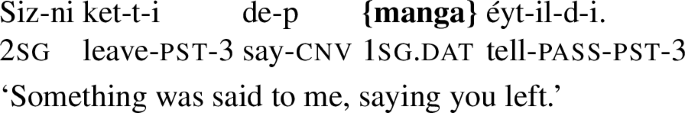

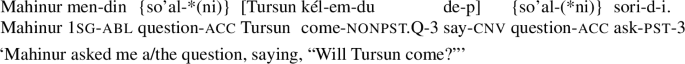

Based on this analysis, dep clauses should appear in environment where they are clearly unselected, unlike simple complementizers. This is precisely what we find in cases like (5), where the content it introduces is construed as a reason or excuse offered by the matrix subject.

-

(5)

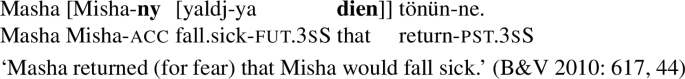

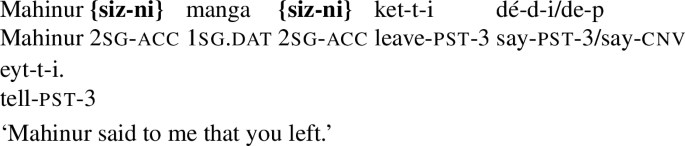

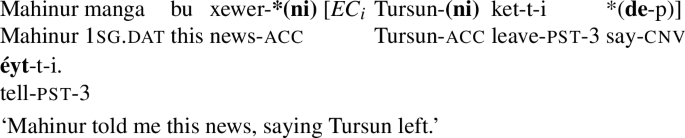

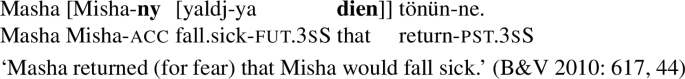

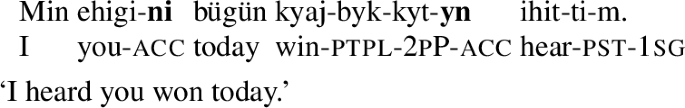

Once motivating a novel analysis of dep clauses, I turn to its implications in the domain of case theory. Notice in (5) that the subject embedded under dep has accusative case. This construction is roughly equivalent to Sakha (Northeastern Turkic) data discussed by Baker and Vinokurova (2010) (henceforth B&V), provided in (6).

-

(6)

During the Government and Binding/Principles and Parameters era, Burzio (1986) proposed a positive correlation between the introduction of an agent and the assignment of accusative case, encapsulated as “Burzio’s Generalization.” Since Chomsky (2000), much of the syntactic literature on case has analyzed accusative case as the result of an Agree(ment) relationship between a Probe (an active v) and a Goal (usually the direct object). I refer to this approach as Case-by-Agree.Footnote 3 Based on B&V’s treatment of dien as a simple complementizer, there is no transitive verb in (6). Given that accusative case arises despite the absence of a v, B&V argue in favor of a different theory of case, Dependent Case Theory (henceforth DCT), which is a configurational theory of case assignment based on Marantz (1991). Under this theory, Burzio’s Generalization results from a c-command relation between two NP arguments within the same local domain (the same phase).

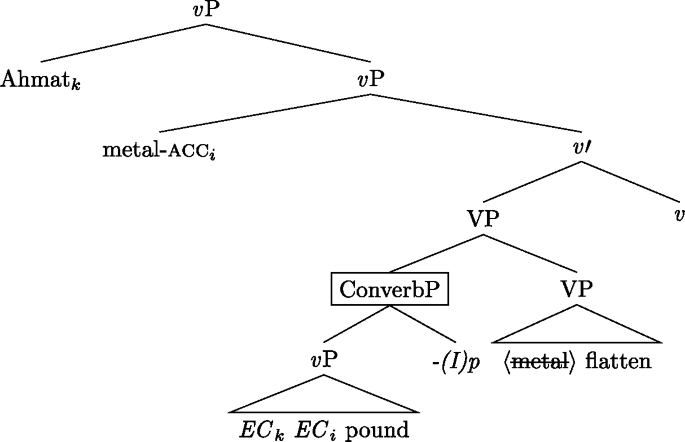

Just as dep is the converbial form of the verb ‘say’ in Uyghur, the same is true of dien in Sakha (the converbial suffix in Sakha is -(E)n). Under the present proposal, as indicated in (5), cases like (6) contain the verb ‘say,’ which resurrects analyses that associate accusative case with an active v, as shown in (7).

-

(7)

When de- ‘say’ is the matrix verb, (7) is embedded under matrix T. In dep contexts, (7) is embedded inside a converbial -(I)p clause, which can either adjoin to VP or TP. As a result, it is possible to account for cases like (5) and (6) via Agreement with the v within the extended projection of ‘say’ using Case-by-Agree. However, I also introduce an alternative proposal, by which Agreement with v is responsible for triggering movement that feeds application of DCT. The present proposal sharpens the ability for Case-by-Agree or DCT to account for the accusative case facts.

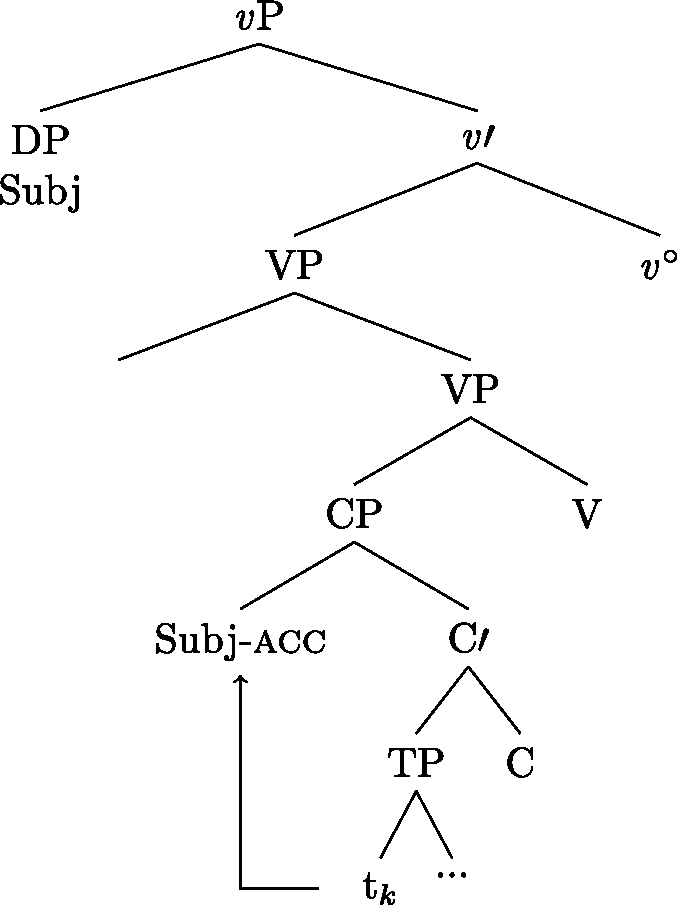

In the end, I argue that the structure in (7) is embedded within an -(I)p clause in dep contexts, giving rise to a configuration where there is a v associated with the matrix verb and another associated with ‘say,’ making it possible for both clauses to license accusative case. In (8), ‘tell’ selects an object that can raise into the specifier of the matrix v. The v associated with ‘say’ is similarly able to assign accusative to the embedded subject, via the same process as (7). This analysis that I build throughout the paper is provided in (9).

-

(8)

-

(9)

The structure above illustrates a VP-level dep clause. A TP-level dep clause differs only in its attachment height. Put more concretely, the de- structure in (7) is embedded under -(I)p, which can attach at both heights, as illustrated in (4).

Turning to case theory, sentences like (6) have appeared to be one of the most compelling cases against any theory that correlates accusative case with transitive verbs. For this reason, it seemed that an alternative theory, such as DCT, was needed to explain environments that really seem to lack a transitive verb, despite the presence of accusative case. The analysis put forth in this paper eliminates the problems imposed by the accusative subjects in cases like (5) and (6) by arguing for the presence of ‘say,’ which resurrects theories like Case-by-Agree that assume a link between accusative case and transitive verbs. In this way, these accusative subjects reduce to run-of-the-mill Raising-to-Object or ECM configurations. For this reason, one of the implications of this paper is that it is a contribution to the debate about whether Case-by-Agree is truly insufficient (Baker 2015; Marantz 1991; McFadden 2004; Yip et al. 1987) and also whether Dependent Case Theory is sufficient or necessary (Šereikaitė 2021).

Zooming out, this paper makes several empirical, methodological, and theoretical points. One has to do with the assumptions that we make when analyzing data from (at least) understudied languages. The questions asked in this paper follow from taking the morphology at face value (i.e. dep is ‘say’ + cnv). Most of the questions that led to the empirical findings in this paper would not have been asked if not for this initial step. Furthermore, looking at naturalistic data led me to discover how many cases did not follow from a prototypical ‘that’-CP analysis of dep clauses. This paper stresses the importance of at least entertaining the analytical possibility that the morphology is as it seems, even for items that appear to be functional. In applying this approach, this paper offers a novel analysis of ‘say’ clausal adjuncts, which alternate with genuine clausal complementation structures. Although the idea that clausal complementation could involve adjunction is not novel, the morpho-syntactic properties and semantic contributions of ‘say’ and the linker is. It is this part of the analysis that leads to several other theoretical contributions related to Case Theory, indexical shift, direct quotation and beyond. The findings in this paper can likely be extended to ‘say’ complementation structures in other languages, as well.

This paper is structured as follows. In Sect. 2, I offer an analysis of -(I)p constructions, demonstrating that they are adjuncts that merge at either VP or TP. Section 3 shows that dep clauses exhibit the same external distribution as -(I)p clauses and that dep itself does not distibute like or behave like a complementizer. Section 4 introduces a brief background of case theory, particularly as it has been discussed in Turkic. Section 5 discusses properties of clauses introduced by de- ‘say,’ particularly focusing on how to determine whether a clause is transparent or opaque, the position of accusative subjects and proleptic objects, and how there are shared properties between accusative subjects and objects more generally. Section 6 demonstrates that the re-analysis of dep clauses introduced in Sects. 2–4 is able to account for a wide range of issues related to accusative case assignment in Uyghur. Sections 7 and 8 offer some discussion of the implications of this work and conclusions.

2 Converbial -(I)p and dep

The purpose of this section is to demonstrate that dep constructions distribute and behave like converbial -(I)p constructions. Given that the distribution of dep clauses is unlike (e.g.) ‘that’ clauses in English, I suggest the null hypothesis should be that the morphology transparently indicates that these are converbial constructions. This section builds upon Sugar (2019) and Major (2021), demonstrating that -(I)p clauses are able to adjoin to VP or TP.Footnote 4 I then demonstrate that the same holds true of dep clauses. On this basis, I suggest that dep clauses are converbial constructions containing the verb ‘say.’

In this section, I first demonstrate that there are -(I)p clauses that merge as (roughly) VP modifiers. I then show that there are other -(I)p clauses that merge higher, roughly at TP. I demonstrate that the height of merger has consequences for both the syntax and semantics. I then briefly discuss the status of empty categories and extraction out of these adjunct clauses.Footnote 5

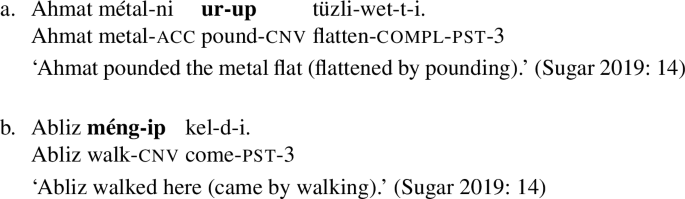

2.1 VP-modifying -(I)p

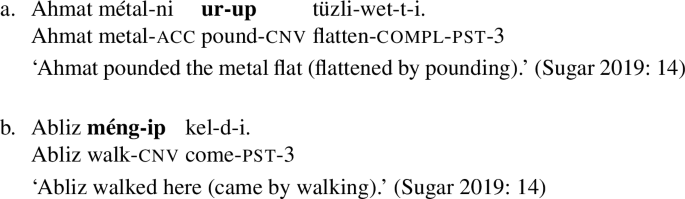

In (10), the bolded -(I)p clause is interpreted as a VP-modifier in both cases. In (10a), the -(I)p clause indicates the manner in which the ‘flattening’ took place. In (10b), the -(I)p clause indicates the manner in which the subject ‘came.’

-

(10)

One reason to assume that these -(I)p clauses merge low in the structure comes from the fact that they are interpreted relative to the aspect specified in the matrix clause. For instance, the manner (pounding) is interpreted as progressive, despite the fact that it not marked for progressive (11a). When it does have progressive marking, the meaning shifts to one in which two independent activities are taking place: pounding metal and flattening metal, but crucially without the reading in which there is a direct causal relationship between them (11b).

-

(11)

The case in (11a) is incompatible with a context in which there is a lapse in time between the pounding and flattening—the manner reading is obligatory and the pounding cannot precede the initiation of the flattening event and all pounding is linked to the flattening event. The latter case is compatible with any context where Ahmat is in the process of hitting metal and flattening it, either consecutively or simultaneously, but the pounding is not responsible for causing the flattening.

The same situation arises for the completive aspect, which is found on the matrix verb in (10a). Completive aspect on the main verb applies to both the matrix VP and the manner-modifying -(I)p clause. It is only able to appear on the main verb, without giving rise to an entirely different interpretation, by which the completive aspect applies to the two events independently (12). The acceptable interpretation in this case would be that two events are completed: a pounding event and also a flattening event.

-

(12)

The structure corresponding to the completive is very low in the clausal spine (Cinque 1999). The fact that the -(I)p modifier merges below completive aspect-marking is highly suggestive that it merges low in the VP region. When a single instance of the completive occurs, it is interpreted such that the manner in which the flattening was carried out was ‘by pounding’ and that both actions are completed. It should also be noted that there are clear prosodic differences between the manner and “other” readings. Like English, the manner reading lacks a substantial break, while the “other” reading generally requires comma intonation.

An additional piece of evidence suggesting that these -(I)p clauses merge low in the structure is that manner adverbials that modify the main predicate are able to occur to the left of the converbial-marked predicate:

-

(13)

The fact that this adverb is able to modify the main verb ‘flatten,’ yet appears higher than the converbial marked verb, supports the analysis that these are truly VP-modifying -(I)p clauses. Given standard assumptions about Turkic (Baker and Vinokurova 2010; Öztürk 2005; Sugar 2019; a.o.), that manner adverbs adjoin to (roughly) VP, a position below the landing site of accusative objects, we can conclude that the converb-marked verb ‘pound’ merges within the extended projection of VP.

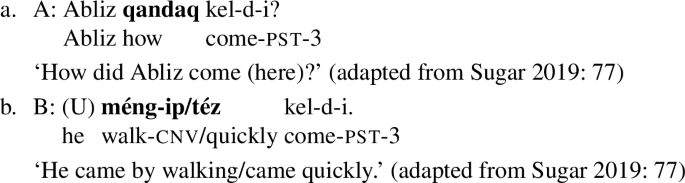

2.2 Differentiating between VP-level and TP-level -(I)p

The next section offers some additional discussion of TP-level -(I)p clauses, but some of the clearest evidence in favor of analyzing a subset of -(I)p clauses as VP modifiers comes from the ways in which they differ from TP-level -(I)p. For this reason, I discuss both types here, which will later be shown to be observed for dep clauses. First, VP-level -(I)p clauses are possible answers to ‘how’ questions, while TP-level -(I)p clauses are not. Second, I show VP “ellipsis” constructions, where VP-level -(I)p clauses can be interpreted within an elided VP, while TP-level cannot. I then illustrate that the position for matrix accusative objects is higher than VP-level -(I)p, but lower than TP-level -(I)p. Finally, I show that Negative Concord Items can be licensed by matrix negation within a VP-level -(I)p clause, but not a TP-level -(I)p clause.

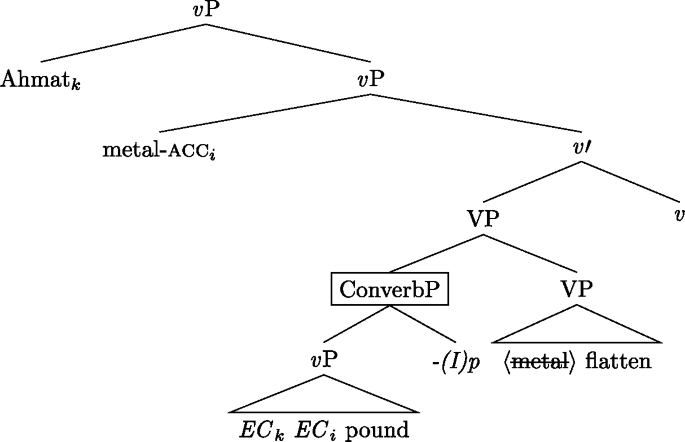

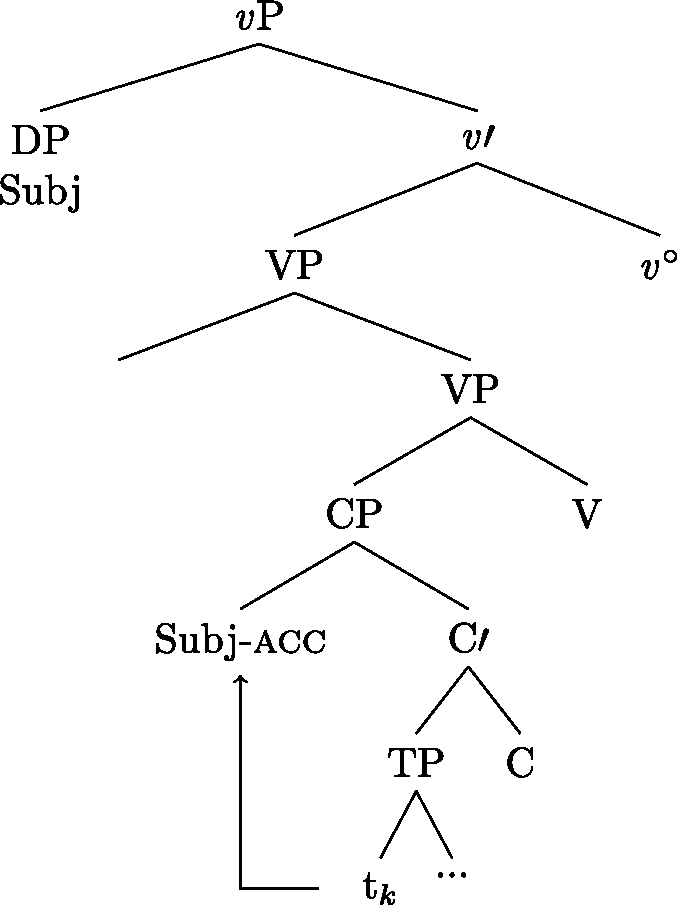

I argue that VP-level -(I)p clauses should be analyzed as shown in (14).

-

(14)

From this point forward, all cases that I refer to as VP-level -(I)p constructions are potential answers to ‘how’ questions, can function as the antecedent for anaphoric elements shundaq/undaq ‘like this/that,’ and occur below the landing site of accusative-marked matrix objects, which I illustrate next. One other note: Uyghur is a discourse pro-drop language, leading to arguments often going unrealized. For the time being, I represent these null arguments as Empty Category (EC) and offer more detailed discussion in Sect. 2.4.

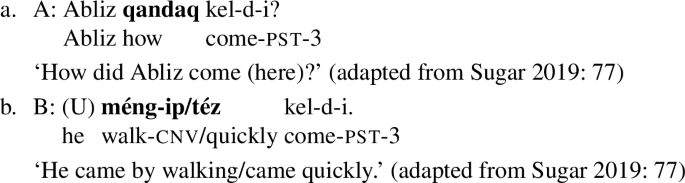

Both -(I)p clauses in (10) are able to function as answers to ‘how’ questions, shown in (15) and (16). Insertion of a manner adverbial is similarly sufficient to answer the same questions.

-

(15)

-

(16)

Given that -(I)p clauses in these cases correspond to answers to manner questions, it is reasonable to conclude that these elements are VP manner modifiers. Turning to cases where the -(I)p clause merges in the TP region, an -(I)p clause is not a VP modifier, which makes it an insufficient answer to a ‘how’ question ((17b) is an acceptable answer to a ‘why’ question).

-

(17)

The same difference is observed between VP-level -(I)p and TP-level -(I)p in the context of the anaphoric element shundaq ‘like this.’ Shundaq is able to stand in for -(I)p when it modifies the VP (18a), but not when it attaches at the TP (or higher) level (18b).

-

(18)

Another way to track the relative height of -(I)p is to look at the position of -(I)p relative to accusative case. Most cases introduced thus far involve two predicates that share the same internal argument, which makes it difficult to tell whether the overt argument is introduced by one predicate or the other. One way to avoid this issue is to ensure that the manner is an intransitive predicate, such as (19a), where it is clear that the accusative object occurs to the left of a predicate (‘run’) that does not license an accusative argument. This is a hallmark of VP-level -(I)p. When there is a shared object, introducing a part-whole relation, as is the case in (19b) makes it possible to show that there are actually two accusative positions. This is a property of TP-level -(I)p, where there are two independent events involving two direct objects (often only one overt) that are related only temporally (e.g. one does not describe the manner of or cause the other).Footnote 6

-

(19)

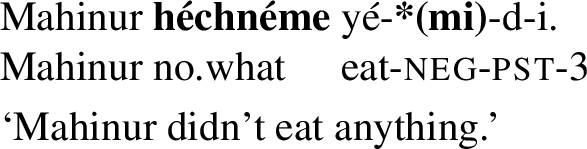

We can gain further insights about the clause structure of -(I)p clauses by considering Negative Concord Items. More specifically, there are a series of elements that contain the negative quantifier héch-, which require clausemate negation (Asarina 2011; Major 2022; Sudo 2012). This is exemplified in (20).

-

(20)

Illustrating the clausemate condition for negation and NCIs, notice that an NCI object within an embedded clause (finite or participial) cannot be licensed by matrix negation:

-

(21)

It is possible for an NCI object introduced by the matrix verb to be licensed by matrix negation (22). In a case such as this one, the NCI object is associated with both verbs.

-

(22)

By using the same type of part-whole relation discussed for (19b), we can show that the construction is a TP-level -(I)p clause and we see that matrix negation is unable to license the NCI object associated with the verb ‘make.’ The same holds for (23b), where andin forces a consecutive interpretation of the TP-level -(I)p clause, which similarly prevents licensing of hte NCI object.Footnote 7

-

(23)

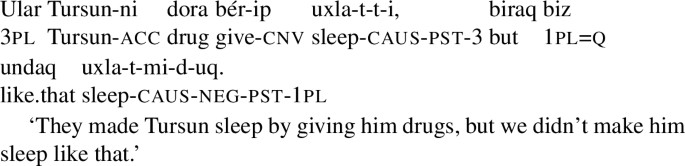

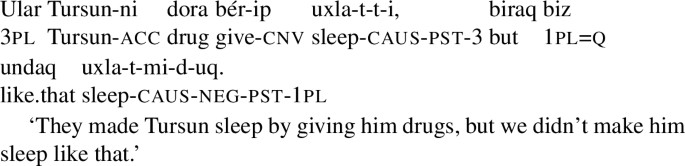

Unlike NCIs contained within TP-level -(I)p clauses, all elements contained within VP-level -(I)p clauses can be licensed by matrix negation. This is made especially transparent by looking at ditransitive level VP-level -(I)p clauses, such as ‘by giving.’ Before showing the NCI data, however, it is first necessary to show that this construction passes the diagnostics introduced for VP-level -(I)p. Notice that ‘giving drugs’ is able to function as the answer to a ‘how’ question (24) and is also interpreted within the ‘shundaq’ VP in (25).Footnote 8

-

(24)

-

(25)

Turning back to NCIs, notice that all elements contained within the VP-level -(I)p clause can be replaced with NCIs licensed by matrix negation (26). First, consider the base sentence (26a), which allows Tursun to be introduced as the causee of the main predicate (accusative-marked) or as the indirect object of ‘give’ within the -(I)p clause. Notice that it is possible to license an NCI indirect object within the -(I)p clause (26b), a direct object (26c), or even a subject (26d).Footnote 9

-

(26)

This section has provided various forms of evidence that there are differences between VP-level -(I)p clauses and TP-level -(I)p clauses and diagnostics to tease them apart. I now provide additional information about TP-level -(I)p clauses.

2.3 More on TP-level -(I)p

Whereas VP-modifying -(I)p constructions encode manner or directional information, TP-modifying -(I)p constructions are far less restricted. Notice in (27) for instance, that there are three distinct events taking place, which are most naturally construed as sequential. Only the final verb is inflected for tense and agreement and each -(I)p clause is followed by a substantial prosodic break, which is not true of VP-level -(I)p.

-

(27)

Also unlike VP-level -(I)p, it is possible for the reference time (the time in which each event takes place) to be distinct, even across days without overlap. However, there is a strong preference for the clauses to be introduced in sequential order. For this reason, (28a) is acceptable, while (28b) is unacceptable.

-

(28)

The main point is that any two predicates can be combined via TP-level -(I)p, because a temporal/sequential relationship is an acceptable default. This is unlike VP-level -(I)p, where the -(I)p predicate must be a potential modifier of the matrix VP.

Another property of TP-level -(I)p constructions is that the entire -(I)p clause (including its subject) precedes the entire matrix clause, as shown in (29).Footnote 10

-

(29)

In this case, the two clauses are sequentialy related and the most natural interpretation also involves causation (i.e. applying makeup causes the cheeks to redden). However, this is not a relationship required in this construction by -ip, but is rather the most natural interpretation within a set of possible interpretations. It is similarly possible that the application of makeup has nothing to do with the reddening of the cheeks (e.g. ‘you’ blushed due to some factor after doing makeup). One additional consequence of this data is that the subject of the -(I)p clause has 2SG features, while the subject of the lower clause has 3rd person features, which is realized on the matrix verb. I extrapolate from this that the subject generated in the matrix clause is actually silent and triggers agreement, while the subject of the -(I)p clause does not.

Finally, a mismatch in voice is possible between a TP-modifying -(I)p clause and the matrix clause (passive and active respectively), as shown in (30).

-

(30)

Combined with (12), TP-level -(I)p clauses are almost entirely independent of the matrix clause with respect to all material embedded under T (voice, aspect, etc.). This differs from VP-level -(I)p modifiers, which obligatorily share the same aspectual properties as the matrix VP. Given that TP-level -(I)p constructions allow an active versus passive mismatch, yet do not allow a mismatch in T, I assume the structure to be slightly larger in TP-level -(I)p clauses, which I represent as VoiceP (I remain agnostic with respect to the precise syntax of passives here).Footnote 11

Based on linear order, availability of differences in Aspect and Voice, the availability of the temporal adjunct andin ‘and then,’ and the inability for an NCI to be licensed within the matrix clause, I assume that these elements merge at (at least) TP, as shown in (31).Footnote 12

-

(31)

In summary, regardless of the merge position of the -(I)p clause, there is a single T head allowed in only the matrix clause. In TP-level -(I)p clauses, the entire clause precedes the matrix clause. In VP-level -(I)p clauses, the entire clause precedes the matrix VP (but occurs below the matrix position where accusative case is assigned). A sentence containing both TP- and VP-level -(I)p constructions is provided in (32), which is schematized in (33).

-

(32)

-

(33)

2.4 Empty categories, extraction, and NCIs

In addition to describing where -(I)p merges, there are other issues that should be addressed before moving to dep clauses. The first is that these are adjuncts that are often transparent for extraction, which appear to be in violation of the Adjunct Island Condition (Ross 1967). Second, it is necessary to address the status of null arguments in -(I)p clauses.

Despite showing island sensitivity across a wide range of configurations, extraction from -(I)p clauses is possible when both clauses have the same subject, as shown in (34).

-

(34)

When the two clauses have distinct subjects, extraction is no longer permitted (35). (35b) demonstrates that the main clause object cannot be fronted, while (35c) illustrates that the object cannot scramble out of the -(I)p clause.Footnote 13

-

(35)

Offering a formal account for why these clauses are transparent is outside the scope of this paper. What matters for present purposes is that extraction is permitted out of same subject -(I)p clauses in general. For this reason, if dep clauses are -(I)p clauses, we should not expect them to be islands either.

The second issue that requires some discussion is the status of null arguments. For both VP- and TP-level -(I)p constructions, it is possible for the -(I)p clause and the matrix clause to have the same subject, where one instance is null (36a), or different subjects, where both are overt (36b).

-

(36)

I take the availability of an overt DP in this position to be evidence that there is always a subject licensed in that position. In this sense, this element is similar to pro. On the other hand, one might notice that this element behaves like canonical Obligatory Control (OC) PRO (see Landau 2013). It is obligatorily co-referent with the matrix subject, the closest c-commanding DP. Due to this mixed behavior, I refer to this null element as EC. I direct the reader to Sundaresan and McFadden (2017) for extremely similar discussion of Tamil and some analytical possibilities.Footnote 14

What is critical to the present paper is that -(I)p constructions in general are not island sensitive and that there is mixed behavior with respect to subjects of -(I)p clauses. For this reason, if we assume that dep clauses are -(I)p clauses, we should assume that same subject dep clauses should be transparent for extraction and that subjects of dep clauses should exhibit mixed behaviors between pro and PRO.

2.5 Interim summary

This section has demonstrated that there are two primary types of -(I)p construction: VP-level -(I)p and TP-level -(I)p, which differ with respect to the height at which they merge, their role with respect to event structure, and transparency/opacity. Furthermore, like English gerunds, both silent and overt subjects are possible.

3 Dep clauses as -(I)p clauses

The purpose of this section is two-fold. First, I demonstrate that the properties of dep clauses mirror the properties of -(I)p clauses more generally. There are VP-level dep clauses and TP-level dep clauses, which are roughly equivalent to the properties discussed for VP-level and TP-level -(I)p in the previous section. I then provide evidence that dep clauses are best analyzed as -(I)p clauses, not as CP complement clauses headed by dep. I then close out the section by discussing what ‘say’ actually means—it often does not denote a communicative act or audible speech directed at an addressee.

3.1 Dep clauses are -(I)p clauses

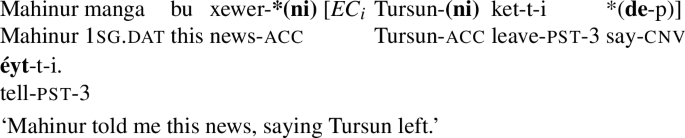

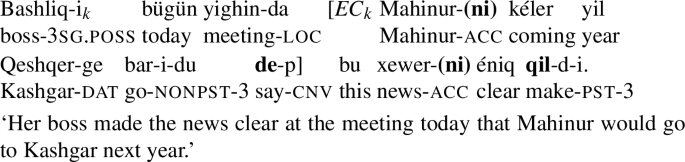

The goals of this section are as follows: i) demonstrate that dep clauses never behave like complements to verbs or nouns, and ii) show that the analyses of -(I)p clauses in the previous sections offer an explanation for the patterns that are observed. In other words, I argue that the dep clauses in cases like (37a) and (37b) are both -(I)p constructions. From this point forward, I assume translations involving ‘saying’ to be more accurate but sometimes offer multiple translations for clarity.

-

(37)

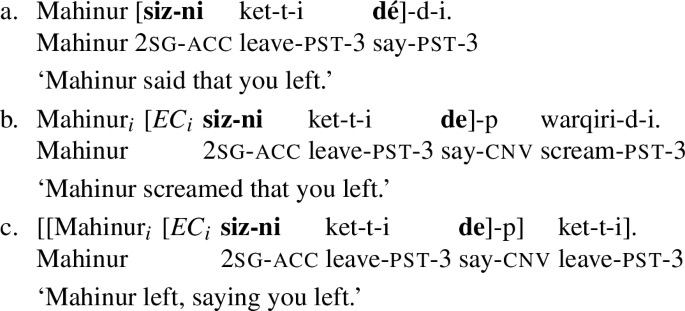

B&V argue that the equivalent to (37a) in Sakha involves standard complementation, while (37b) involves adjunction. Under the present analysis, both structures involve adjunction, but it is possible for the adjunction to occur at different heights. Cases like (37a), which look like standard CP complements to the verb, are generally VP-level -(I)p constructions, while (37b) is naturally construed as either a VP- or TP-modifying -(I)p clause. One goal of this section is to illustrate that dep clauses distribute like -(I)p clauses. A second goal of this section, which continues into Sect. 3.2, is to illustrate that dep clauses should not be treated as CPs headed by dep, selected by nouns or verbs.

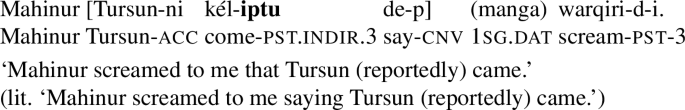

If we consider cases where ‘say’ combines with an unergative predicate like ‘scream,’ the ‘say’ clause modifies ‘scream’ and coerces it into a verb of speech.Footnote 15 Thus, the matrix clause in (38) is simply ‘Mahinur screamed,’ while the dep clause indicates that there was a communicative component involving some propositional content (i.e. ‘Tursun left’).

-

(38)

I take the dep clause in (38) to be a manner modifier, as was the case for VP-level -(I)p clauses.

First, notice that when ‘say’ is a main verb, it is able to introduce a DP complement, which is obligatory (39a). ‘Scream,’ on the other hand, is incompatible with a complement (39b).

-

(39)

The same facts hold for participial clauses. ‘Say’ obligatorily takes a complement (40a), while ‘scream’ is incompatible (40b).

-

(40)

However, despite the fact that ‘scream’ cannot introduce a CP directly, de- ‘say’ can, and must. ‘Say’ then combines with -(I)p and the entire clause is able to adjoin to the VP headed by ‘scream,’ as was the case in (38). By adjoining dep to ‘scream,’ we find that the subcategorization requirements of de- ‘say’ emerge, and ‘say’ obligatorily introduces an internal argument (41).

-

(41)

The facts above would be rather surprising if dep is a simple complementizer. In particular, requiring a complementizer to introduce a DP argument is atypical (e.g. Mary screamed/believes/knows/heard (*that) something). However, under the analysis put forth here, this behavior is expected. ‘Say’ is a transitive verb, selects a DP complement, and adjoins to the matrix VP headed by ‘scream’ in (41a). The same applies to the clausal DP in (41b).

Under the present analysis, other verbs that are able to modify a screaming event should be compatible in place of dep. This is precisely what we find for verbs like oyla- ‘think.’ Of course, this is describing a cognitive event that occurred as part of the screaming event, but this is precisely what we would expect under a converbial analysis, where the -(I)p clause modifies the matrix VP: the ‘think’ clause specifies some aspect of the main verb ‘scream.’

-

(42)

The contrast between ‘say’ and ‘think’ is expected if we take the difference between (41) and (42) to result from differences between de- ‘say’ and oyla- ‘think.’ It is unclear to me what an alternative analysis would look like or how it would be more informative that taking the morphology at face value.

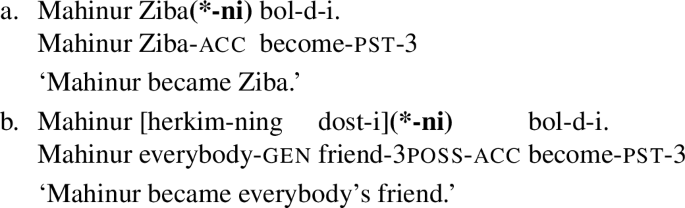

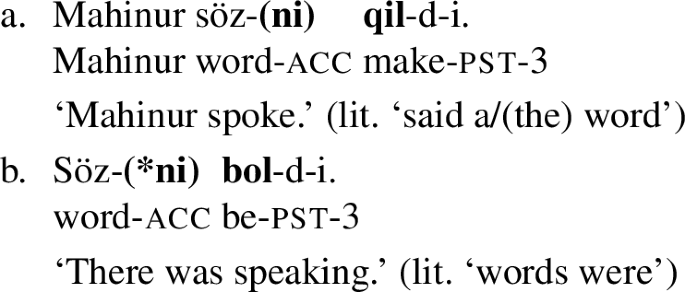

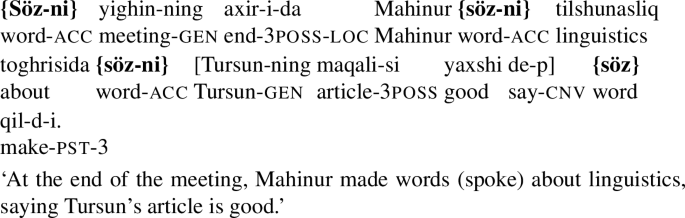

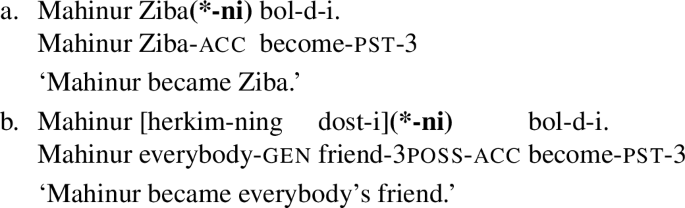

Additional evidence that dep introduces an internal argument to the structure comes from light verb constructions. The contrast between qil- ‘do/make’ and bol- ‘become’ shows a clear transitivity alternation (43).

-

(43)

Notice that ‘make word’ is transitive, requiring an Agent, while the unaccusative bol- ‘become’ takes ‘word’ as the grammatical subject (43b). It is standardly assumed that one difference between cases like (43a) and (43b) is that the latter lacks v altogether, or that both cases have different ‘flavours’ of v (Folli and Harley 2005).Footnote 16

If dep clauses were CP arguments, one would expect there to be a correlation between transitivity of the matrix predicate and the ability to license a dep clause. Notice in (44) that the dep clause is permitted regardless of which Light Verb is present. If dep were selected by a transitive verb, we would expect dep to be introduced in (44a) but not in the intransitive structure in (44b).

-

(44)

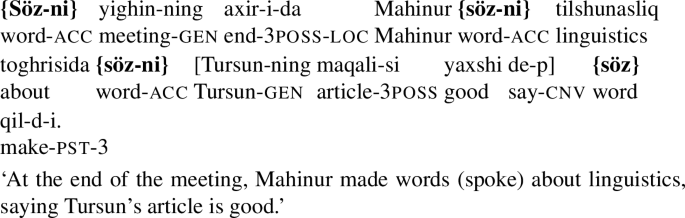

One could argue that the transitivity alternation does not determine the availability of a dep clause because the dep clause is a CP selected by ‘word,’ in which case the structures above would be a type of Noun-complement constructions. This is not the case, however, given that ‘word’ is able to scramble around the dep clause, as shown in (45).

-

(45)

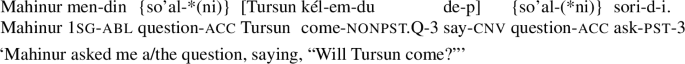

With this in mind, we can turn to a communicative predicate that is able to introduce an indirect and direct object, such as eyt- ‘tell’ in (46). Notice that dep is able to occur in addition to ‘news,’ which is also able to scramble independent of the dep clause.Footnote 17

-

(46)

The patterns above would be less convincing if one were generally able to scramble head nouns away from the clauses that modify them, but this is not the case in general. For instance, if we turn to relative clauses (47a), notice that the entire relative clause can scramble (47b), but not the head to the exclusion of CP (47c).

-

(47)

The same is true for standard N-complement constructions, which are similarly built from participles (48a). It is possible for the entire N-complement constituent to scramble (48b), but it is not possible for the head noun to scramble on its own (48c).

-

(48)

The fact that dep clauses in these configurations do not behave like complex NPs is unsurprising if we adopt the adjunction analysis proposed here. Under the present analysis, the dep clause in (46) is an adjunct, which allows the matrix object to scramble around it like any other VP-modifier or VP-level -(I)p construction. This is unlike the complex NPs in (47) and (48), which are constituents, preventing the head from scrambling independent of the clause it selects.

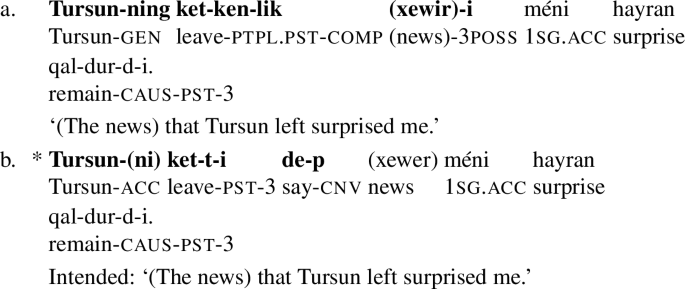

Another reason to assume that dep clauses are not standard CPs (i.e. arguments) comes from their inability to function as subjects of a psych predicate like ‘make surprised.’ This distinguishes them from participial clauses, which do behave more like ‘that’ clauses. Notice in (49a) that the participial clause is able to serve as the grammatical subject (including nominative case), unlike dep clauses (49b).Footnote 18

-

(49)

Notice that when the causative morpheme is removed in (50), the resulting predicate is unaccusative (50a). For this reason, adjunct participial clauses (with ablative case) are not arguments and are permissible (50b). With the same reasoning, because dep clauses are always adjuncts, they are able to adjoin to the VP in (50c), just as was the case with warqira- ‘scream’ and söz bol- ‘word become.’

-

(50)

All of the data in this section follow from an analysis by which dep clauses are adjuncts and non-oblique participial clauses are arguments. Dep clauses do not seem to form constituents with nouns or verbs in any of the cases outlined above, whereas participial clauses behave almost exactly like run-of-the-mill English CPs with ‘that.’ For this reason, I suggest that dep clauses involve the (by now) familiar structure in (51).

-

(51)

Based on the analysis in (51), there is no syntactic difference between the dep clauses above and any other VP-level -(I)p construction.

For completeness, it is worth demonstrating that TP-level dep clauses also exist. One example of this is provided in (52), where ‘say’ is used in a sequence of events.

-

(52)

Let us now reconsider dep clauses that occur with predicates like ‘leave,’ as in (53).

-

(53)

It was shown for standard -(I)p clauses that matrix negation can license an NCI in a VP-level -(I)p clause, but not in a TP-level -(I)p clause. The same pattern is observed for VP- versus TP-level dep clauses:

-

(54)

Furthermore, when dep combines with ‘think,’ the dep clause can be co-referenced with shundaq/undaq, as shown in (55a), but this is not possible when it combines with ‘leave’ (55b).

-

(55)

As was shown for -(I)p clauses in general, dep clauses can combine with predicates like ‘think’ or ‘scream,’ in which case they pass the VP-level -(I)p diagnostics provided in Sect. 2, functioning as manner modifiers. In cases where dep combines with predicates where ‘saying’ is entirely independent of the matrix verb, it behaves like TP-level -(I)p. In the latter case, it can be interpreted as part of a sequence of events (52) or as a reason (53).

I suggest that cases like (53) involve the same structure as TP-level -(I)p constructions, as shown in (56).

-

(56)

3.2 Additional arguments against dep as a prototypical complementizer

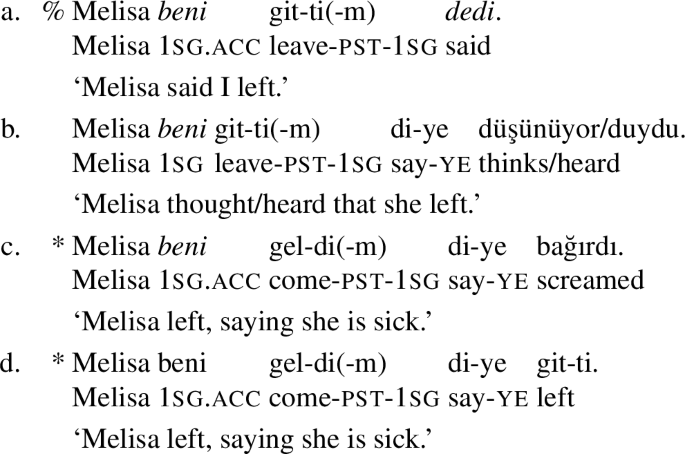

The empirical argumentation to this point certainly favors the idea that there are uses of dep that are incompatible with a simple complementizer analysis. However, as a reviewer points out, this does not eliminate the possibility that dep is sometimes a standard complementizer. Doxastic predicates (e.g. believe, think, know) are perhaps the most difficult to explain under the present analysis. In other words, a case such as (57) could be naturally treated as an environment where dep is a simple complementizer that heads a CP selected by ‘think.’

-

(57)

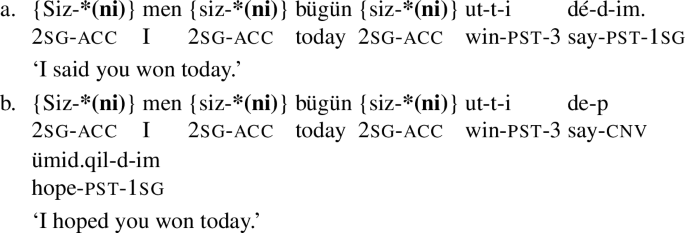

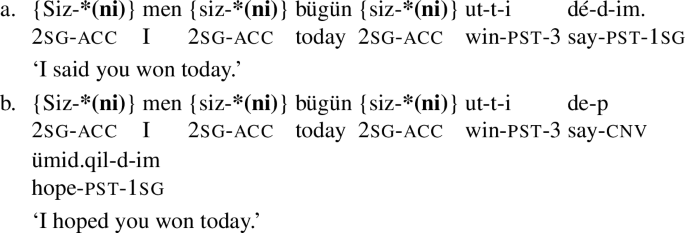

One reason to think that these structures are not CPs headed by dep comes from looking at questions and answers targeting the object of verbs like oyla- ‘think,’ where there are two possible targets of wh-questions: the DP that is ‘thought about’ and the reported content (i.e. the dep clause). Notice in (58a), that ‘who/what-ACC’ can be used to target the internal argument of ‘think.’ As an alternative, it is possible to introduce two wh-expressions: ‘what/who-ACC’ and ‘how’ (58b).

-

(58)

(58a) is most naturally answered by a nominal arguments, such as (59a) or (59b), but speakers also find (57) to be acceptable. (58b), on the other hand, can only be answered by (57), which supplies an answer to both questions (the accusative element answers ‘what’). If we adopt the present analysis for (57), there is an argument introduced by the main verb (what is thought about), corresponding to ‘what/who-ACC’ and the -(I)p clause (corresponding to ‘how’).Footnote 19

-

(59)

Another type of question is available that is extremely informative with respect to the syntax of these configurations. This involves using néme ‘what’ to target the clause introduced by dep, which is not compatible with qandaq ‘how,’ shown in (60). Crucially, this question must be answered with (57).

-

(60)

If dep were a simple complementizer, it is unclear how the data above could be possible. The fact that a ‘how’ question targets a dep clause and a ‘what’ question targets the complement to dep does not follow from an analysis where dep is a complementizer. Furthermore, it would be highly unusual for one to use a different wh-expression when a complementizer is stranded (‘what’) compared to when the complementizer is included in the question (‘how’). This falls out naturally from the present analysis where the constituent containing dep is an adjunct clause headed by -(I)p and the complement to de- ‘say’ is a CP argument. Recall that the ability to be the answer to a ‘how’ question was presented as a diagnostic for VP-level -(I)p clauses in Sect. 2.

Another argument in favor of an adjunction analysis comes from the behavior of factive predicates. In recent literature, factivity alternations based on properties of complement clauses have received considerable attention (Bochnak et al. 2021; Bondarenko 2020; Moulton 2009; Özyıldız 2017). Notice in (61) that a predicate like ‘know’ has a different interpretation when it takes a participial complement (61a), as opposed to occurring with dep (61b).

-

(61)

When ‘know’ selects a participial clause as its complement, the truth of its propositional content is presupposed to be true by the speaker. In other words, in (61a), the continuation in the ‘but’ clause forces a contradiction. This is not the case in (61b), however, and a contradiction does not arise. This is unexpected if ‘know’ selects the dep clause as its complement. This pattern is predicted by the present analysis, because the dep clause is a VP adjunct.

Sudo (2012) assumes that there are two distinct bil- verbs in Uyghur, one corresponding to ‘know’ and the other to ‘believe.’ In other words, there is a factive and non-factive version of bil-. There are two reasons that this approach is not preferable. The first is that ‘know’ remains presuppositional even when there is a dep clause in the structure. Notice in (62) that the speaker is committed to the existence of some ‘news’ that is in the common ground but not committed to the truth of the content introduced by dep, because ‘say’ is not a factive predicate.

-

(62)

A second reason that we should avoid the homophony approach is that the same facts hold for a wide range of factive predicates (63). In other words, we would need to assume two separate lexical entries for each of the verbs below, a problem that does not exist if we take dep clauses to be clausal adjuncts, not unlike other converbial clauses.

-

(63)

The adjunct analysis of dep clauses in Uyghur is highly reminiscent of the analysis of Washo clausal complementation, where an adjunct clause linking element similar to converbial -(I)p introduces non-factive clauses, while a different strategy is required for factive verbs (Bochnak et al. 2021). Uyghur suggests that factive interpretations arise from predicates taking a nominal complement, while non-factive interpretations arise via adjunction. The present proposal suggests that the adjunction site is at VP, which is outside the scope of the factive predicate.

On a related note, there are some predicates, such as ‘forget,’ that require the embedded clause to scope low. In one case, it is the entire embedded proposition that is forgotten, while in the other, it is not the case that the proposition is what is forgotten.

-

(64)

Predicates of this variety are an important test case for the present discussion, because it predicts that this is precisely the environment where the English ‘that’ clause translation will be impossible. Notice that when a participial clause is embedded under ‘forget,’ it is compatible with ‘forget that p’ in English (65a). Dep clauses, on the other hand, cannot have this meaning, as shown in (65b).

-

(65)

Again, treating dep clauses as akin to ‘that’ clauses does not have an explanation for the non-factivity of factive predicates, nor does it predict that a predicate like ‘remember’ should exhibit behavior distinct from ‘forget.’ Under the present analysis, dep clauses adjoin at two heights, neither of which is in the scope of the attitude/communication predicate. This predicts that dep clauses should exhibit different behaviors from participial clauses, which do occur within the scope of the attitude predicate. For these reasons, combined with those spelled out in the previous section, I suggest that dep clauses are never internal arguments in Uyghur.

3.3 What is ‘say’?

At first glance, it may seem controversial to claim that ‘say’ is present in all dep constructions from a purely intuitive perspective. The fact that ‘say’ elements do not always encode the physical production of speech in clausal complementation environments is likely one of the primary reasons that the possibility that these elements are verbs is often dismissed. A serious investigation of the lexical status of ‘say’ in clausal complementation environments requires an analysis of ‘say’ as a main verb. In other words, it is only possible to argue that dep does not contain the lexical verb ‘say’ if we have a list of properties or axioms that define what ‘saying’ is. It turns out that defining ‘say’ is not that easy in English and beyond. From a typological perspective, it was shown in Munro (1982) that ‘say’ exhibits many idiosyncracies. In Chickasaw, for instance, the complement to ‘say’ does not display the object marker or object agreement expected for other verbs. It is also shown that subjects of ‘say’ in some languages, such as Samoan, do not receive ergative case-marking, which is expected on subjects of transitive verbs. Throughout the rest of this section, I suggest that ‘say’ exhibits a dynamic versus static alternation that gives rise to different syntactic and semantic properties, potentially offering an explanation for some of Munro’s observations as well.

Starting with English, ‘say’ is often used as a stative predicate, as shown in Grimshaw (2015), Major and Stockwell (2021), and Major (2021). In such environments, ‘say’ does not directly encode a speech event. It instead communicates a Source or Location and the content that it communicates (or communicated). This is most unambiguously shown for certain inanimate subjects like sign (66).

-

(66)

(66a) most is most naturally interpreted as a dynamic speaking event involving the agent, Mary. However, (66b) and (66c) are both instances where ‘say’ is clearly unaccusative, describing a state where the sign indicates the location of linguistic material, not a communicative event. In some cases, the subject is inanimate, but the Source is also introduced:

-

(67)

I got a message from Dad yesterday.

In both cases above, it is difficult to figure out exactly what the difference in meaning is between (67a) and (67b). It is clear in both cases that Dad is not presently producing speech. These strictly involve the reporting of the content whose Source was Dad, which holds present relevance in the discourse. I suggest that (67a) involves ‘say’ used as a stative predicate, in following with Major (2021).

Before expanding on the point made above, it is worth first discussing a doxastic predicate like ‘think,’ whose prototypical use (at least in the simple present) is commonly assumed to be stative. Özyıldız (2021), for instance, shows that a stative versus dynamic alternation exists for ‘think,’ which determines the types of complement clause that it selects. Özyıldız argues that for declarative complements, ‘think’ may introduce a stative description (68a)–(68b). While the simple present, which favors a stative reading, is incompatible with an interrogative complement (68c), the present progressive that favors a dynamic reading is compatible with an interrogative complement (68d).

-

(68)

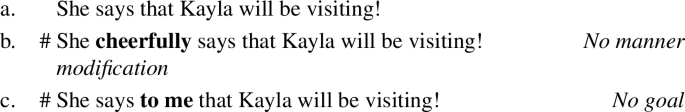

There is no doubt that ‘say’ is able to introduce an activity description, but it is perhaps more controversial that it introduces a stative description, particularly when the subject is animate. To bring out this contrast, it is perhaps easiest to consider the behavior of ‘say’ in the simple present. As discussed by Dowty (1979), the hallmark of a stative predicate is that they have a present tense interpretation that is neither habitual nor interpreted in the narrative present, as discussed by Özyıldız for ‘think.’ I make this argument for ‘say’ below.

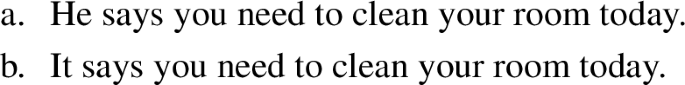

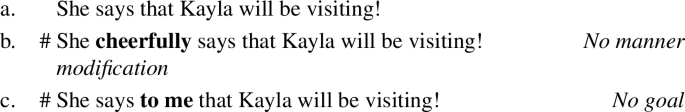

I now illustrate the stative versus dynamic alternation for ‘say’ and show that it has syntactic consequences; namely, ‘say’ in the simple past is naturally construed as dynamic and takes manner modification and is natural with an overt Goal (addressee) argument (69). In the simple present, a stative construal obtains and manner modification and a Goal argument are not permitted (70).Footnote 20

-

(69)

I met Katie for the first time yesterday and she produced exactly one utterance.

-

(70)

I met Katie for the first time yesterday and she produced exactly one utterance.

First notice that both the simple past and simple present forms of ‘say’ are possible (69a)–(70a), despite the fact that the actual speech event took place in the past. The past tense form naturally introduces the speech event description, which makes manner modification, as in (69b), or a goal, as in (69c), natural. However, “stative” say does not encode the speech event itself; instead, it introduces the source and the content that the source communicated that holds some relevance to the present discourse. In other words, the cases in (69) naturally encode the actual act of speaking (out loud), while (70) forces you to infer that some kind of communicative act took place.Footnote 21

There is much more to be said about stative uses of communication predicates, but much of this discussion is outside the scope of this paper. For present purposes, my primary concern is to demonstrate that ‘say’ is a semantically light verb, which can indicate the physical production of speech (the prototypical use) or simply indicate the relationship between a source and content the source is responsible for communicating, without introducing a description of the actual communication event. Minimally, this brief discussion of English was intended to convince the reader that ‘say’ has different senses and the way in which it is most naturally interpreted is dependent on context.Footnote 22

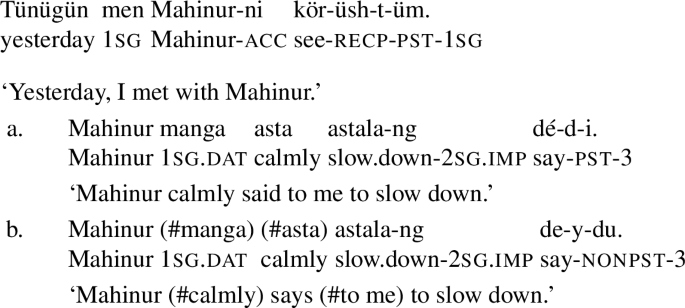

Turning back to Uyghur, there are a few points that need to be addressed in relation to the discussion above. First, I show that ‘say’ exhibits some of the same properties as English say: it can be a stative predicate, the precise sense of ‘saying’ has implications for modificational possibilities and which arguments can be expressed, and how these possibilities are constrained further by the environment in which ‘say’ appears. In other words, if there are (at least) two types of ‘saying,’ the environment in which they occur will determine which is preferred or perhaps even which is possible.

As was the case for English, it is possible for inanimate subjects of ‘say’ (71), where ‘sign’ gets locative case. These are impersonal constructions that introduce communicated content and the source of that content without encoding ‘saying out loud.’Footnote 23 In such a case, a Goal argument is not permitted (71b).

-

(71)

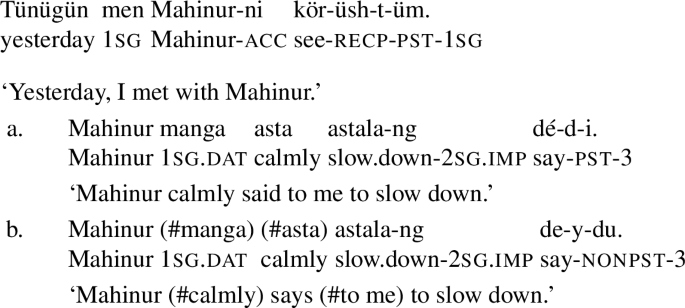

Because both stative and dynamic descriptions are available, context plays a crucial role in determining which version is being used. Using inanimates is a good way of biasing towards the stative reading. If we take (72) to be the lead-in sentence, which sets the communicative event in the past, it is possible to introduce a goal and manner modifier in the past tense (72a), similar to English. Similar to the cases involving the English simple present, the non-past in Uyghur favors the stative reading of ‘say,’ in which case a goal argument and manner modification is prohibited (72b).Footnote 24

-

(72)

Lead-in sentence:

One property worth noting here, which will be discussed in more detail later, is the status of the complement clause introduced by ‘say.’ These clauses behave similar to bare arguments. For instance, they must remain adjacent to de- ‘say’ and cannot scramble, just like bare objects. For this reason, I take these clausal complements to merge as complement to V, where they remain.

-

(73)

The cases above suggest that there are multiple senses of ‘saying,’ which has implications for which arguments and modificational possibilities.

Given that there are multiple ‘senses’ of say, which differ not only their semantics, but also with respect to certain morpho-syntactic properties, it is worth noting that the version of ‘saying’ that is most natural in a given environment will impact both the interpretation of ‘say’ in that environment, the ability to introduce manner modifiers, or Goal arguments. More concretely, consider a case where a dep clause functions of a VP headed by ‘scream.’ In this case, the most natural construal will be that what was said (‘Tursun apparently came’) was done out loud by ‘screaming’ and this ‘screaming event’ was directed at ‘me.’Footnote 25

-

(74)

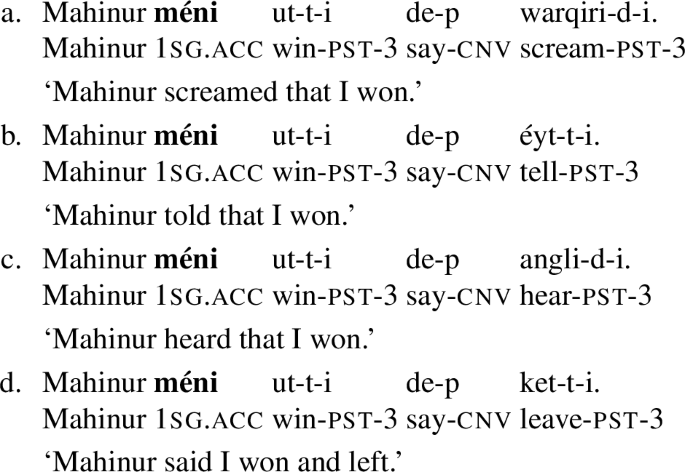

One aspect of dep clauses in general is that they are able to introduce an evidential that is relativized to the Source, not the speaker. In other words, the choice of -iptu in (74), as opposed to the direct past -Di, reflects what was actually communicated by Mahinur. In thi sense, the contents of the dep clause represent the most accurate depiction of what was communicated by the matrix subject to the matrix speaker, independent of the speaker’s actual beliefs.

A predicate like ‘scream’ naturally combines with ‘saying’ on intuitive grounds. For a predicate like ‘think’ in (75), it is possible that the speaker is reporting the matrix subjects thoughts on the basis of something that they uttered, but this is not a strict requirement, as pointed out by an anonymous reviewer. However, it is necessary that the subject is responsible for somehow communicating the content of the embedded proposition to the speaker. In a case like (75a), the speaker indicates that ‘Mahinur’ communicated to them that ‘Tursun came’ and that it was not based on reportative evidence. In (75b), on the other hand, it must be the case that Mahinur communicated to the speaker that the evidence was based on someone else’s report.

-

(75)

In this way, the ability to report (75b) is contingent upon a linguistic speech act or some other act capable of indicating that the thoughts being reported were based on reportative evidence (it is unclear what this could be). If the communication was from a sign or inference, then this option is lost, resulting in the most generic form of the past. In other words, there are aspects of the communicative act that are directly encoded in dep clauses, even when they occur with predicates like ‘think.’ This differs from participial complements to ‘think,’ such as (76). In cases such as this one, the topic of ‘Tursun’s having come’ must be in the discourse, and the speaker simply indicates Mahinur’s stance. The speaker does not introduce the proposition from Mahinur’s perspective; instead, the speaker simply indicates what Mahinur thinks about the proposition.

-

(76)

Consider a context where Tursun travels a long distance to campus and has a meeting planned with the speaker. The speaker needs to cancel and emails Tursun, hoping he’ll see the message before he leaves. In this case, in a discourse about whether Tursun ended up coming, (76) would more naturally be used. This is because the embedded participial clause is not introducing new information from the perspective of Mahinur, only that Mahinur ‘thinks’ that what we’re discussing is the case.Footnote 26

The primary take-home message of this section is that ‘say’ is semantically bleached, even as a main verb. Sections 3.1–3.2 demonstrated that dep clauses behave like the verb ‘say’ and the converbial marker -(I)p. This holds even if the precise meaning of ‘say’ is not completely obvious when it combines with a main verb like ‘think.’ This does not make ‘say’ any less of a verb from a syntactic perspective. It is because ‘say’ is semantically weak, that it is compatible with ‘saying out loud,’ ‘saying internally,’ ‘responsible for communicating,’ or even ‘indicated that p.’

3.4 Preliminary summary

This section has offered an analysis of converbial -(I)p constructions, suggesting that they merge at VP and TP. The merge height has both morpho-syntactic and semantic consequences. VP-level -(I)p clauses modify the matrix VP and are thus restricted by the same spatio-temporal parameters as the matrix VP, generally yielding a simultaneous interpretation. TP-level -(I)p constructions merge outside the scope of matrix T, but lack a TP projection. Unlike VP-level -(I)p, which merges below the matrix subject, TP-level -(I)p clauses precede the entire matrix clause. Arguments are often shared across -(I)p clauses, but pronounced only once, when identical.

Furthermore, I have demonstrated that dep clauses do not behave like CPs selected by verbs or nouns. However, Uyghur does have another type of CP that does behave and distribute more like ‘that’ clauses in English; namely, constructions involving participials, which look and behave like DPs. I have shown that participial clauses behave like arguments, exhibit similar interpretive properties to ‘that’ clauses (e.g. factivity), and lack the “root-like” properties of finite CPs embedded under de- ‘say.’ I have shown that none of these properties extend to dep clauses and that a decompositional analysis treating dep as the sum of its parts does offer an explanation for these differences (77).

-

(77)

Finally, ‘say’ is an extremely abstract verb that can introduce a stative description in some environments and an activity description in others. For this reason, I suggest that the same alternation should be possible when ‘say’ combines with other predicates. When ‘say’ combines with a predicate that can be construed with articulation (e.g. ‘cry’ or ‘scream’), it is likely that it will be interpreted as ‘saying something out loud to someone.’ When ‘say’ combines with a doxastic predicate, it is more likely to be construed as stative. In this sense, we do not need to posit multiple types of dep; instead, the variability arises from ‘say’ being semantically bleached and the consequences of the converb being able to merge at different heights.

4 Background on case theory

The previous section introduces a new analysis of complementation constructions involving dep, which argues that dep clauses are actually clausal adjuncts headed by the verb ‘say.’ Across the dep constructions in the previous section, many contain accusative subjects. I argue that ‘say’ plays a critical role in licensing accusative subjects in the next section, but I first introduce some relevant details regarding Case Theory, based on Baker and Vinokurova (2010) (B&V). I begin by introducing B&V’s discussion of DCT and Case-by-Agree. I then turn to how both theories of case operate in simple mono-clausal constructions in Uyghur, primarily focused on constructions discussed by B&V for Sakha. I conclude by discussing predicate nominals and the role that v plays in accusative assignment.

4.1 Dependent case theory and case-by-agree

The formal mechanics of DCT introduced in Baker and Vinokurova (2010: 595: Ex. 4a–4b) are provided in (78).Footnote 27

-

(78)

In DCT, case is determined by a confluence of factors: i) the c-command relationship between two DPs both in the same local domain (i.e. phase), ii) which phase the c-command relation occurs in, and iii) whether either of the NPs has already been assigned case. It is well-known across Turkic that accusative direct objects derive from raising out of their merge position (Baker and Vinokurova 2010 for Sakha; Kelepir 2001, Kornfilt 1997, Öztürk 2005 for Turkish; Major 2021, Shklovsky and Sudo 2014, Sugar 2019 for Uyghur). For B&V, the position where accusative is assigned is at the edge of VP, which they argue to be a phase edge. As a consequence of the object raising into the edge, it becomes accessible to the higher phase for case calculus. The raised object, being the lower of two NPs within the higher phase, gets accusative case, as schematized in (79). Objects that do not raise, on the other hand, are inaccessible to the higher phase and remain unmarked. In Baker (2015), a minor modification is made; namely, the internal object raises into the specifier of v (80). This option is more in following with standard assumptions regarding phasehood, because v is treated as the phase head. As far as I am aware, both (79) and (80) make the same prediction: whenever the internal argument raises into a position accessible to the higher phase, it will receive accusative case as long as there is a c-commanding NP argument in the higher phase.

-

(79)

-

(80)

Deriving accusative case with Case-by-Agree is hardly distinct from (80). The only substantive difference is that under B&V’s Case-by-Agree, it is an active v that is responsible for accusative-assignment (based on Chomsky 2000, 2001), as spelled out in (81).

-

(81)

If a functional head F ∈{T,D} has unvalued phi-features and an NP, X, has an unvalued case feature [and certain locality conditions hold], then agreement happens between F and X, resulting in the phi-features of X being assigned to F and the case associated with F being assigned to X. (Baker and Vinokurova 2010: 596)

The relevant head for accusative case is v, which is able to assign accusative case only when an argument that is still an available target for Agree is merged within its c-command domain. If Agree is successful, the probe (v) attracts the DP goal that it Agrees with into its specifier, as illustrated in (82).

-

(82)

If we assume Case-by-Agree with respect to (81), it is Agree that is responsible for accusative case. I demonstrate that this option is able to account for all instances of accusative case in Uyghur. I entertain an alternative analysis, however, by which Agree is strictly responsible for triggering movement (and possibly also specificity), which feeds the DCT rule responsible for accusative case (78b). These two options make almost identical predictions, with one exception. Under Case-by-Agree, one would expect that only v is capable of licensing accusative case. Under DCT, any functional head that triggers movement of a DP into a higher phase is capable of licensing accusative case. I represent the relevant feature on v as [+acc/spec]. Under Case-by-Agree, I assume the feature [+acc] to be implicated. For DCT, I assume the relevant feature to be [+spec], but it is possible that this feature is simply an EPP Feature that forces movement into spec, vP. It is standardly assumed that probes containing strong features trigger movement.

Given that both of these analyses can account for the data, differentiating between them is not straightforward. If we take the particular type of v discussed above to be responsible for both assigning accusative case and triggering movement, the prediction would be that environments that lack v (or at least the strong feature-bearing v) will not trigger movement nor case assignment. Predicate nominals provide some evidence in favor of the Case-by-Agree analysis, where a defective v neither assigns case nor triggers movement. This is not insurmountable for DCT, but the existence of a direct relationship between environments involving movement and the presence/absence of accusative case requires an independent explanation.

4.2 Accusative case in mono-clausal constructions

The previous section introduced the technical details of case theory. This section illustrates how each theory accounts for monoclausal structures. Simple transitives exhibit (unmarked) nominative case on the subject (83a) (nominative case is unglossed elsewhere) and apparently optional accusative-marking (-ni) on the object. In ditransitives, the internal (theme) argument optionally gets accusative case, while the recipient/goal obligatorily receives dative case (83b). In Uyghur, the presence of accusative case indicates specificity, meaning that the presence of accusative in cases like (83a) indicates whether or not there is a particular apple in the discourse or not. Bare objects are assertive and thus introduce a new referent to the discourse.

-

(83)

In this sense, the presence or absence of accusative case is not truly optional, but instead is discourse conditioned, functioning as so-called Differential Object Marking (DOM).Footnote 28

One piece of evidence for raising comes from the relationship between the direct object and manner adverbials, such as téz ‘quickly’ (a diagnostic also used by B&V for Sakha). When the direct object occurs to the right of the manner adverbial, it is obligatorily bare and interpreted as non-specific, as in (84a), while it must be accusative-marked when it occurs to the left of the adverb, as in (84b).

-

(84)

Under Case-by-Agree, the v associated with ‘eat’ either agrees with the direct object and attracts it into its specifier, in which case it receives accusative case, or it remains adjacent to the verb and does not get accusative case. For present purposes, I do not commit to a particular analysis of low, unmarked NPs. However, there are many licensing options in the literature that are compatible with this data, such as assuming that bare NPs pseudo-incorporate into the verb, e.g. (Baker 2014; Massam 2001; a.o.) or that there is a low, silent accusative licenser.

Regardless of how bare objects are licensed, it is clear that they remain low in the VP and are interpreted as non-specific indefinites. Accusatives require raising and are interpreted as specific. Under DCT, there is no formal link between the movement trigger, the specific interpretation, and accusative assignment. That is, accusative case and the specific interpretation occur because of movement, but there is no way of predicting where movement will or will not be triggered. With this said, the DCT representation of (84) is presented in (85).

-

(85)

Under B&V’s analysis, the subject is merged into the higher phase, while the direct object merges into the lower phase. In order for the DCT accusative rule to apply (78b), both NPs must be within the same phase. Thus bare objects, which do not raise, are not accessible to the higher NP and cannot get accusative case. Objects that raise to the edge of the VP phase (or higher) are accessible to the subject, thus receiving accusative case.

Expanding this discussion to include dative arguments, Uyghur exhibits the same behavior as Sakha. When the direct object linearly follows the indirect object and is adjacent to the verb, it only optionally bears accusative marking (86a).Footnote 29 When the direct object precedes the indirect object, it must bear accusative marking and is interpreted as specific, as shown in (86b).

-

(86)

From the perspective of Case-by-Agree, the dative argument is introduced by some (perhaps Applicative) head associated with ditransitive verbs, while accusative is directly linked to the v responsible for introducing the Agent. Under DCT, B&V argue that VP-internally (i.e. within the lower, VP phase), the higher of two unmarked NPs gets dative case. It is the subsequent raising of the object to the edge of the lower phase that allows it to get accusative case, as illustrated in (86). This is schematized in (87).

-

(87)

The structures in (87) illustrate how both dative and accusative rules apply based on the DCT rules proposed by B&V. Dative is assigned VP-internally. If the direct object remains in its merge position, it remains bare (87a), and if it raises to the edge of VP, it becomes accessible to the higher phase, resulting in it getting accusative case. It should be emphasized here, that there are not any differences between Uyghur and Sakha (at least related to case) up to this point.

4.3 Predicate nominals

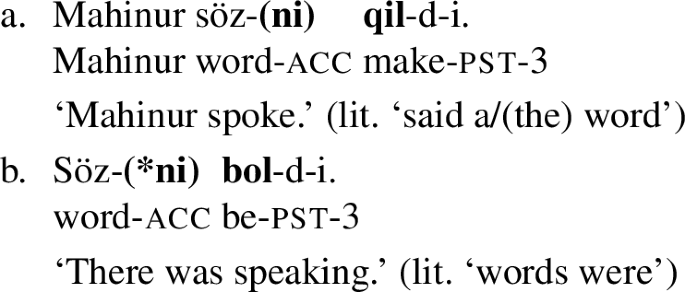

One final configuration of interest before moving back to clausal complementation involve predicate nominals, such as (88). These are configurations where the lower of two NPs never gets accusative case, which also happens to be a cross-linguistically robust pattern, noted as a potential problem for DCT in Baker (2015). Under the present proposal, as long as we correlate movement with a particular strong feature on v (e.g. [+acc/spec]), accusative case can straightforwardly be ruled out with predicate nominals involving ‘become’ by suggesting that ‘become’ cannot host the relevant feature. For this reason, proper names, quantificational DPs, and other referential internal arguments that otherwise obligatorily get accusative case with transitive verbs, are unable to receive accusative case in (88).

-

(88)

Put in other words, if we take [+/-acc/spec] to be a feature of active v and assume that bol- lacks v or that it has an unaccusative v, the nominal would obligatorily remain within VP. Recall that nominals that remain within VP even in transitive constructions pseudo-incorporate into the verb. If we assume the same process to take place here, these low nominals pseudo-incorporate into the verb and essentially behave like complex predicates with bol- ‘become.’ For DCT, if we assume v\(_{\textsc {become}}\) to be incapable of triggering movement, accusative would never obtain in these contexts due to the lower NP never being local enough to the higher subject.

As mentioned in Sect. 2.4, Uyghur light verbs (e.g. ‘become’ and ‘do/make’) are responsible for transitivity alternations that determine argument/event structure and case properties. We see in (89) a clear distinction between the choice of light verb and the case properties, where transitive ‘do’ can license accusative case (89a), while the unaccusative bol- ‘become’ cannot (89b).

-

(89)

In Sect. 5, there are cases where the subject of ‘say’ is inanimate and accusative case cannot be licensed. I suggest that properties of v in such constructions are responsible for licensing accusative case. For the present, I strictly wish to suggest that associating movement/case with v offers an explanation for the absence of accusative case for inchoatives and predicate nominals, whether we assume v to be responsible for triggering movement and case-assignment (Case-by-Agree) or only the former (DCT).

5 Accusative subjects, finiteness, indexical shift and ‘say’

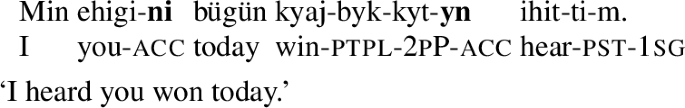

At this point, I have argued for a novel analysis of dep clauses and introduced sufficient background on case theory. I now introduce the general properties of accusative embedded subjects and their position within the clause, and I offer an explanation for why they are able to raise out of a tensed clause without inducing a Phase Impenetrability Condition (PIC) violation. The goals of this section are two-fold: i) introduce the general patterns of accusative subjects,Footnote 30 and ii) briefly introduce the relationship between finiteness and indexical shift discussed in Shklovsky and Sudo (2014) and Major (2022). I begin by demonstrating that accusative subjects merge within the embedded TP and raise out, which aligns with the Sakha data discussed by Baker and Vinokurova (2010) (B&V). I then introduce prior literature on Uyghur accusative subjects, clause size and finiteness, and briefly discuss prolepsis. I then demonstrate that accusative subjects exhibit behavior that is similar to accusative objects.

5.1 Accusative subjects merge low and raise

The purpose of this section is to show that the basic hallmarks of accusative subjects discussed by B&V for Sakha, also hold for Uyghur. This section demonstrates that accusative subjects merge within the embedded TP and subsequently raise, keeping in mind that there is a nearly identical proleptic object construction that I return to in Sect. 5.2. The evidence for raising configurations comes from NCI licensing, idioms, and a combination of the two, building from similar diagnostics applied in Baker and Vinokurova (2010), Shklovsky and Sudo (2014), and Major (2022).

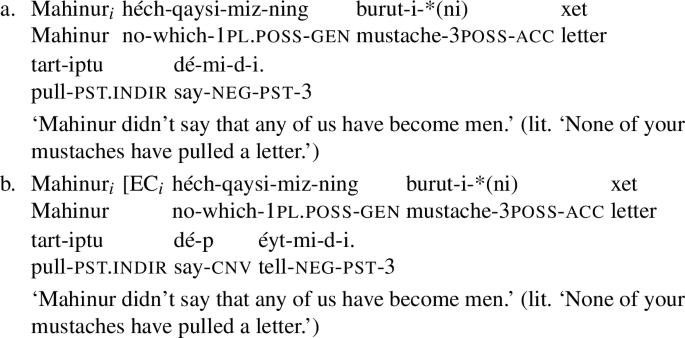

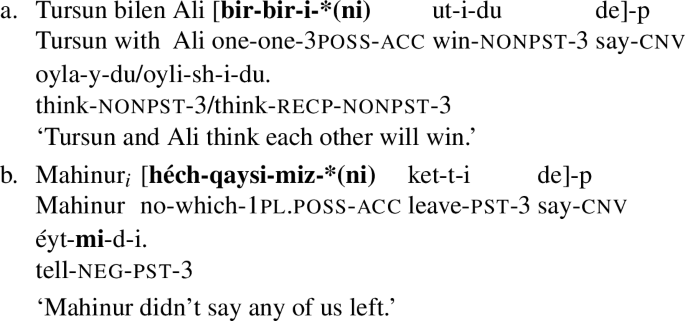

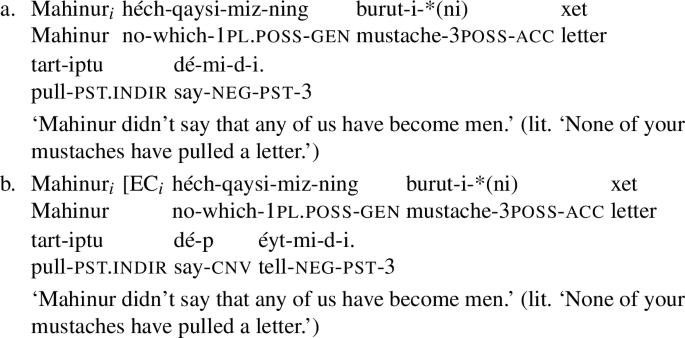

Importantly, héchqaysi-miz-ni ‘none of us’ can be licensed by embedded negation, as shown in (90), which entails that it originates within the embedded clause, since the matrix clause is affirmative. This holds for both main verb de- ‘say’ (90a) and within a dep clause (90b).

-

(90)

This serves as one piece of evidence against a so-called prolepsis analysis, by which accusative subjects merge in the matrix clause and co-refer with a resumptive pronoun in the embedded clause.Footnote 31 I address the fact that the embedded verb exhibits 3rd person agreement in the next section.

A second piece of evidence involves idiom chunks. Subjects of sentential idioms must merge locally as part of the idiom in order to receive an idiomatic interpretation. The idiom is provided in (91a) and is embedded under ‘say’ in (91b) and within a dep clause that combines with ‘think’ in (91c).

-

(91)

Even when it carries accusative case in (91b)–(91c), the idiomatic interpretation remains. This serves as additional evidence that the accusative subject originates downstairs, since the idiomatic interpretation holds. The NCI and idiom tests demonstrate that the accusative subject originates downstairs but do not actually demonstrate that they raise, which I turn to now.

Shklovsky and Sudo (2014) and Major (2022) both provide data showing that accusative elements are higher, due to accusative case being obligatory for binding by the matrix subject or for an NCI to be licensed by matrix negation. However, as a reviewer points out, as soon as we acknowledge the existence of both proleptic objects and raising derivations of accusative elements, it is unclear which construction one is diagnosing if not coupled with another diagnostic. Notice that accusative case is obligatory for both the reciprocal in (92a) and (92b). This was used in by both aforementioned authors to illustrate that the embedded subject must raise to the position where accusative case is acquired to be local enough to the matrix subject or matrix negation for binding or NCI licensing. However, there is nothing that illustrates that (92a) or (92b) involve raising, as opposed to prolepsis, meaning that there are two possible interpretations. One possibility is that the embedded subject raises to a position local to the matrix clause for accusative-licensing. A second possibility is that the accusative elements in both examples are proleptic objects, in which case they merge in the matrix clause and we cannot conclude anything about raising.

-

(92)

With these issues noted above, it is crucial to show that raising is able to feed binding or NCI licensing. This requires simultaneously providing diagnostics for raising and locality. (93a)–(93b) illustrate this for both matrix de- ‘say’ and dep clauses. First, the idiom test illustrates that the accusative element originated in the clause embedded under de(p). The fact that accusative-marking is obligatory for matrix negation to license the NCI shows that raised accusative-marked subjects meet the clausemate condition for NCIs, while nominatives do not. Finally, whereas the accusative subject in (93a) literally raises to object in the matrix clause, the accusative subject in (93b) raises to object of de- within the dep clause, which is local enough to matrix negation for licensing.

-

(93)

In evaluating this diagnostic, it is important to note that negation on matrix de- ‘say’ is unable to license an NCI object inside the embedded clause. This is true in both nominalized embedded clauses and finite clauses, as shown in (94).

-

(94)

Given that accusative case is obligatory on subjects in (93) and NCIs contained within complement clauses cannot be licensed, we can conclude that the NCI subjects in (93) raise at least high enough to be licensed by matrix negation. In (93a), the accusative NCI is literally in the matrix clause, where it meets the clausemate condition for licensing. In the case of (93b), the NCI raises to the edge of the dep clause. Given that these are examples of VP-level -(I)p clauses, they are also local enough to matrix negation for NCI licensing, as discussed in (54).

5.2 Finiteness, indexical shift, and prolepsis

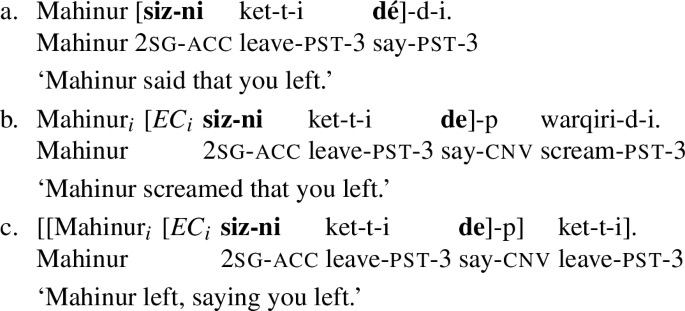

The analysis put forth in this paper suggests that accusative subjects are derived by raising into spec, vP within the extended projection of de-(p) in all cases. Given that clauses embedded under ‘say’ carry root tense, this requires that v Agrees with the embedded subject across a finite CP clause boundary and attracts it into its specifier, which appears to be a Phrase Impenetrability Condition (PIC) violation. Movement of this type, often referred to as ‘hyperraising,’ has been reported across a number of languages.Footnote 32 In Major (2022), it is argued that accusative embedded subjects are permitted only when C is defective, which is made evident by the presence of a default agreement marker on T, -i, as shown in (95).

-

(95)

Notice that the 2SG accusative embedded subject occurs with 3rd person agreement on the embedded verb ‘eat.’ I will show that default agreement is the most reliable diagnostic for raising versus prolepsis shortly. Major (2022) relates this pattern to George and Kornfilt’s (1981) analysis of Turkish. They argue for Turkish that overt agreement correlates with finiteness, while the absence of agreement indicates that the clause is non-finite. In other words, where tense is thought to indicate finiteness in languages like English, agreement have been argued to be the relevant indicators in Turkish. In Uyghur, the verb bears 3rd person agreement (not the absence of agreement), which suggests there is a default agreement marker, unlike George and Kornfilt’s (1981) proposal for Turkish. I do not take a strong stance as to what left peripheral property related to C is defective, but it is clear that is disrupts agreement for both person and number.Footnote 33

Major (2022) attributes default (3rd person) agreement to feature transmission (Chomsky 2004, 2008). More specifically, ‘say’ is able to select (at least) two different types of CP complements, one full, and the other defective. Full CPs are characterized by a nominative subject and matching phi-agreement, while defective CPs have accusative embedded subjects and default phi-agreement.

Full embedded CPs display a process known as Indexical Shift (Schlenker 1999, 2003), by which indexicals (context-sensitive elements like ‘I’ and ‘you’) are interpreted relative to the reported discourse context, as opposed to the present discourse context. In simpler terms, indexical shift is similar to direct quotation, where I in a sentence like John said, “I left.” is obligatorily interpreted as John. The difference is that cases of indexical shift occur in indirect speech reports. An example of indexical shift is shown in (96a), while (96b) demonstrates that indexical shift is not possible when the embedded subject has accusative case (and the embedded verb shows default agreement).

-

(96)

In keeping with Sudo (2012) and Shklovsky and Sudo (2014), Major (2022) argues that a left peripheral “monstrous” operator  (Anand and Nevins 2004) forces 1st and 2nd person pronouns to be interpreted relative to the reported discourse context. It is argued that the monster is only available in full CPs, in which case C is able to successfully transmit features to T, which assigns nominative case to the embedded subject and bears matching phi-features. (96a) is such a case. In (96b), on the other hand, there is no operator, the embedded clause is defective, and as a result, T fails to assign nominative case to the embedded subject or to agree with it. The analysis for defective CPs is provided in (97a), while a full (monstrous) CP is provided in (97b).

(Anand and Nevins 2004) forces 1st and 2nd person pronouns to be interpreted relative to the reported discourse context. It is argued that the monster is only available in full CPs, in which case C is able to successfully transmit features to T, which assigns nominative case to the embedded subject and bears matching phi-features. (96a) is such a case. In (96b), on the other hand, there is no operator, the embedded clause is defective, and as a result, T fails to assign nominative case to the embedded subject or to agree with it. The analysis for defective CPs is provided in (97a), while a full (monstrous) CP is provided in (97b).

-

(97)