Abstract

This paper investigates an interaction between locality requirements and syntactic dependencies through the lens of hyperraising constructions in Cantonese and Vietnamese. We offer a novel piece of evidence from subject displacement in support of the claim that phasehood can be deactivated by syntactic dependencies during the derivation. We show that (i) hyperraising (to subject) constructions are attested in both languages, and that (ii) only attitude verbs that encode an indirect evidential component allow hyperraising constructions. We propose a phase deactivation account for hyperraising, where the phasehood of a CP is deactivated by an Agree relation in terms of an evidential feature with the embedding verb. The findings of this paper suggest that locality requirements in natural languages are less rigid than previously thought, and that there is a non-trivial semantic dimension to hyperraising phenomena.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper investigates an interaction between locality requirements and syntactic dependencies through the lens of hyperraising constructions in Cantonese and Vietnamese.Footnote 1 While certain syntactic heads are held responsible for locality requirements (i.e., they mark the point after which syntactic operations can no longer be applied to a domain; e.g., the projection of a C head constitutes a phase, Chomsky 2000, et seq.), recent proposals suggest that the locality requirements established by phase heads are not set once and for all (Richards 1998; Rackowski and Richards 2005; Nunes 2008; Stepanov 2012; van Urk and Richards 2015; Halpert 2016, 2019; Branan 2018; den Dikken 2018; Branan and Davis 2019; Preminger 2019; Pesetsky 2021; Toquero-Pérez 2021; Carstens 2023a,b). In this paper, we offer a novel piece of evidence in support of the claim that phasehood can be voided by syntactic dependencies during the derivation. It implicates that locality requirements in natural languages are less rigid than previously thought.

We motivate our claim with empirical evidence from a case of subject displacement in Cantonese and Vietnamese. The crucial observation concerns the contrast in (1) and (2).Footnote 2Footnote 3 In the sentences in (1), the matrix subject can be separated/displaced from the embedded predicate (with which it is thematically related).Footnote 4 However, the same displacement is disallowed in the sentences in (2), where a different set of attitude verbs are involved.Footnote 5

In other words, the legitimacy of such subject displacement is contingent on the choice of attitude verbs. This posits an initial puzzle on the licensing condition of subject displacement in both languages. As will be discussed in greater details in Sect. 2, the contrast between (1) and (2) falls under a generalization on subject displacement and indirect evidentiality, given in (3).

We seek to derive (3) from a phase-theoretic minimalist framework. There are two major proposals in our proposal. First, we propose that the subject displacement in sentences like (1) instantiates cases of hyperraising to subject. Second, we argue that hyperraising in Cantonese and Vietnamese is legitimate only when a prior Agree relation in terms of an indirect evidential feature is established between attitude verbs and their clausal complement. Following the spirit of Rackowski and Richards (2005), Nunes (2008), Halpert (2016, 2019), den Dikken (2018), we suggest that such an Agree relation deactivates the phasehood of the embedded CP. An overview of our proposal is given in (4).

The findings of this paper shed light on both syntactic locality and the understanding of hyperraising constructions. First, the data in Cantonese and Vietnamese lend support to the suggestion that phase-induced locality requirements are not established once and for all. Rather, they can be deactivated during the syntactic derivation. Second, the data in Cantonese and Vietnamese highlight an under-studied semantic dimension of hyperraising constructions, namely, evidentiality. Particularly, the data reveal that the distribution of (hyper)raising predicates in different languages may not be entirely idiosyncratic and there are non-trivial semantic dimensions that underlie hyperraising constructions (cf. Şener 2007; Yoon 2007; Horn 2008; Wurmbrand 2019; Lohninger et al. 2022). Such a correlation provides a partial explanation on why predicates participating in cross-clausal A-dependencies are largely similar across languages.

The rest of this paper contains five sections. Section 2 shows that there is a subject-evidentiality correlation as given in (3) in Cantonese and Vietnamese. Section 3 turns to evidence for subject movement. We argue that the movement is an instance of hyperraising. Section 4 details our proposal and derives the empirical properties of hyperraising in Cantonese and Vietnamese. Section 5 discusses how the proposal may capture a similar split in terms of predicates allowing hyperraising in other languages. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2 The evidential split in attitude verbs

In this section, we establish a correlation between subject displacement and an evidential component encoded in attitude verbs in Cantonese and Vietnamese, as stated in (3) above. In Sect. 2.1, we first set up the empirical foundations by revealing a split between two classes of attitude verbs in both languages. We show that only some attitude verbs allow the embedded subject to surface in the matrix subject position. Then, in Sect. 2.2, we suggest that this split among attitude verbs correlates with their evidential requirement on the embedded clause/proposition.

2.1 Displaced subjects in the matrix position

The contrast between (1) and (2) reflects a split between attitude verbs that allow an embedded subject to occupy the matrix subject position and those that do not. The Cantonese data in (5) and the Vietnamese data in (6) reveal the range of verbs that allow a displaced subject.Footnote 6 Note that in most cases the matrix subject is inanimate, which indicates that it is selected by the embedded predicate rather than the matrix attitude verb (i.e., it cannot be the attitude holder).

However, some other attitude verbs disallow such a displaced subject. The examples in (7) and (8) are constructed as minimal pairs with some of the naturally occurring examples above.

The availability of a displaced subject thus divides attitude verbs in Cantonese and Vietnamese into two classes, summarized in Table 1. Anticipating a raising analysis of the displaced subject, we refer to attitude verbs that allow a displaced subject as raising attitude verbs (RAVs), and the relevant constructions as RAV-constructions. Attitude verbs that do not allow a displaced subject are referred to as non-raising attitude verbs (NRAVs).Footnote 7

2.2 The correlation with evidentiality encoded in attitude verbs

We now turn to the correlation between the split in attitude verbs and evidentiality. We reveal that all RAVs share a common semantic property: they all encode an indirect evidential component in their lexical semantics. That is, they require their clausal complements be associated with indirect evidence. In contrast, NRAVs lack this requirement. Additionally, we show that the indirect evidential component can interact with elements such as verbal suffixes and prefixal/lexical negation, which in turn affects the (un)availability of subject displacement.

Before we proceed, we make the following working definitions of direct/indirect evidence for the sake of concreteness (cf. Willett 1988; von Fintel and Gillies 2010; Murray 2014).

2.2.1 Indirect evidentiality vs. non-indirect evidentiality

We observe that RAVs form a homogeneous class in that their clausal complement must be based on indirect evidence in both transitive their usage. The contexts in (10a) and (11a) specify two types of indirect evidence respectively, namely, reportative evidence and inferential evidence (cf. Willett 1988). The sentences in (10) reveal that RAVs such as tengman ‘hear’ are compatible with an (indirect) reportative evidence context (with or without subject displacement), as opposed to NRAVs such as teng-dou ‘hear-accomp’ (where dou here marks successful completion of an action; see more discussions in Sect. 2.2.2). A similar contrast is observed with Vietnamese in (11) as well, where the context specifies (indirect) inferential evidence.

Notably, the contrast is flipped in a direct evidence context. In (12) and (13), the RAVs become infelicitous, whereas the NRAVs are acceptable.

Applying the same diagnostic to other RAVs, we observe that they either require inferential evidence or reportative evidence, or both. In Table 2, RAVs listed as “reportative” are only compatible with contexts like (10), and those listed as “inferential” with contexts like (11). None of them is felicitous in contexts like (12) and (13), however. We suggest that the evidential requirement on RAVs is encoded in their lexical semantics.

It should be noted that the evidential component in RAVs is not unique to Cantonese and Vietnamese. A similar component is said to be present in epistemic modals. For example, von Fintel and Gillies (2010) suggest that epistemic modals in English (and other languages) like must are markers of indirect inference, drawing on evidence from the contrast between (14) and (15). (14) specifies a direct evidence context and (15) an indirect one (von Fintel and Gillies 2010, 353), and epistemic modals are only compatible with the latter.Footnote 8 We suggest that a similar evidential component resides in RAVs.

We stress that the split between RAVs and NRAVs is correlated with the distinction between indirect vs. non-indirect evidentiality, but not indirect vs. direct, or non-direct vs. direct. While the above examples appear to show that some NRAVs require direct evidence (due to the presence of an accomplishment suffix), it is not the general property of NRAVs. For example, NRAVs like Cantonese gokdak ‘think’ and Vietnamese cho ‘think’ do not specify the source of evidence, and thus are compatible with both indirect and direct evidence contexts:

As such, a more accurate characterization of NRAVs is that they all lack the requirement of indirect evidence (i.e., non-indirect). They may require direct evidence (e.g., verbs with an accomplishment suffix), factivity (e.g., verbs like ‘know,’ ‘remember,’ ‘discover’ and ‘regret’) or underspecified evidence. The evidence component of NRAVs can be summarized in Table 3.

Based on these observations, we make the generalization in (17), repeated from (3).

As a remark on the generalization, it is the requirement of indirect evidence on attitude verbs that correlates with the possibility of subject displacement, but not their compatibility with indirect evidence. Although NRAVs like jingwai ‘think’ are compatible with indirect evidence, subject displacement is disallowed in an indirect context, as shown in (18).Footnote 9

2.2.2 Interaction with verbal suffixes

To substantiate the generalization in (17), we show that the indirect evidential component associated with RAVs may interact with certain verbal suffixes, such as -dou in Cantonese and -thấy/-được in Vietnamese. The former indicates “accomplishment or successful completion of an action” and is used to form verbs of perception (Matthews and Yip 2011, 251–252). Likewise, the latter marks experiential or perfective interpretation (cf. Duffield 2017). Relevant to us is that if an RAV combines with these suffixes, it no longer requires indirect evidence, but instead direct (sensory) evidence, as already shown in (10)/(11) and (12)/(13). The verbal suffixes appear to “overwrite” the evidential component lexically encoded in RAVs. Importantly, the suffixed RAV also loses its ability to take a displaced subject (i.e. it becomes a NRAV, see (7a) and (8a)). This conforms to the generalization in (17): when the verbs no longer encode indirect evidentiality, subject displacement is disallowed. The relevant examples that display this interaction are listed in Table 4.Footnote 10,Footnote 11

2.2.3 Interaction with negation

Negation may also affect the ability of attitude verbs to license subject displacement. For example, a RAV ceases to allow subject displacement if it is negated. In sentences in (19), soengseon ‘believe’ and waaiji ‘suspect’ in Cantonese do not allow subject displacement if they are negated by the prefix m- ‘not’ (cf. Yip 1988), as shown in (19). The same pattern is observed in Vietnamese, illustrated in (20).

On the other hand, negation has an opposite effect on NRAVs: an NRAV may allow subject displacement when negated by the prefixed negation m- in Cantonese. Examples include zidou ‘know’ and geidak ‘remember,’ as illustrated in (21).

Vietnamese (không) biết ‘(not) know’ patterns with Cantonese (m-)zidou ‘(not-)know,’ as shown in (22a). Unlike Cantonese, the negated form of nhớ ‘remember’ in Vietnamese is not formed by adding a negation, but instead it is a different lexical item quên mất ‘forget’ (i.e., the antonym of ‘remember’). Nevertheless, quên mất also allows subject displacement, as in (22b). This shows that the availability of subject displacement is not only affected by negation on verbs, but also by lexical semantics of verbs.

Moreover, there is a further interaction between negation and verbal suffixes. Recall that some RAVs cease to allow a displaced subject after taking an accomplishment suffix. In Cantonese, for example, the suffix may be negated by infixing -m- ‘not’ between the verbal stem and the suffix. Crucially, the attitude verbs so formed allow subject displacement again, as exemplified in (23). This shows that while an accomplishment suffix may “overwrite” the indirect evidential component of an RAV with a direct one and turn it into an NRAV, this effect can be “canceled” by negating the suffix.

Vietnamese exhibits similar patterns, except that the negation in Vietnamese precedes both the verb and the suffix, instead of being sandwiched between the verbal stem and the suffix. This is shown in (24).

An anonymous reviewer raises concern on the nature of the interaction between evidentiality and negation. We suggest that the “cancellation” of the lexical evidentiality specification of the attitude verbs (and hence the change of their raising profiles) indeed occurs at the lexical level, rather that the syntactic level. Conceptually, it is implausible for sentential negation to operate directly on featural specification which is determined in the lexical component. Empirically, there is also evidence that the lexical/“constituent” negation that interacts with the subject displacement (raising) possibilities is in contrast with syntactic negation. We briefly discuss these issues below.

First, as mentioned above, while the negation of geidak ‘remember’ (NRAV) in Cantonese is transparent, i.e., m-geidak ‘not-remember’ (RAV) in (21b), the Vietnamese negation of nhớ ‘remember’ (NRAV) is expressed by another lexical item quên mất ‘forget’ (RAV) as in (22b). It shows that the interaction between negation and raising possibilities occurs at the lexical level.

Second, unlike the lexical/infixed negation -m- in (23), the syntactic negation mou fails to change the raising profile of NRAVs like gu-dou ‘guess-accomp,’ as shown in (25) in Cantonese. Hyperraising becomes possible when gu-dou is negated by the infixed -m-, but not mou.

In a similar vein, (high) sentential negation m-hai also fails to affect the raising profile of RAVs, as shown in (26). The RAVs like soengseon ‘believe’ and waaiji ‘doubt’ retain the possibility of allowing subject displacement in the presence of m-hai.

The same patterns carry over to Vietnamese. In (27), with the sentential negation không phải là, the RAV cảm giác ‘feel like’ still allows subject displacement. This contrasts with the lexical negation không in (20), where subject displacement is blocked when không applies to an RAV.

Summarizing the observations, (some) RAVs become incompatible with a displaced subject when negated, whereas (some) NRAVs become compatible with it when negated. We suggest that negation may affect the evidential components encoded in attitude verbs, which subsequently affects the availability of subject displacement.

As a final remark, attitude verbs that come with an underspecified evidential component (such as jingwai/nghĩ ‘think’) have a different profile regarding negation. Their incompatibility with a displaced subject is retained when negated, as illustrated in (28).

We suggest that the underspecification of evidentiality of these verbs indicates a lack of a lexically encoded evidential component. By virtue of this, negation cannot interact with an evidential component and has no effect on subject displacement.

2.2.4 Interim summary

The patterns of attitude verbs regarding subject displacement are summarized below:

Assuming that the indirect evidential component inherent to attitude verbs can interact with verbal suffixes and negation (presumably in some pre-syntactic (e.g., lexical) component), all these observations can be subsumed under the generalization in (3)/(17), repeated below.

3 Hyperraising: Evidence for cross-clausal subject movement

Concerning the syntactic properties of the subject displacement in RAV-constructions, we argue that (i) the subject in RAV-constructions is derived by movement and is not base generated in the matrix clause (Sect. 3.1); that (ii) the movement displays standard properties of A-movement (Sect. 3.2); and that (iii) the movement crosses a (finite) CP boundary (Sect. 3.3). These observations amount to the suggestion that RAV-constructions instantiate genuine cases of hyperraising.

3.1 Movement, not base generation

We argue that the displaced subject in RAV-constructions like (1) is not base-generated in the matrix clause, but is moved from within the embedded clause. We present four pieces of evidence in support of a movement analysis.

The first argument comes from island sensitivity. The displaced subject cannot be thematically associated with an embedded predicate in an island, such as the complex NP island in (31) (which is also a subject island) and the adjunct island in (32).

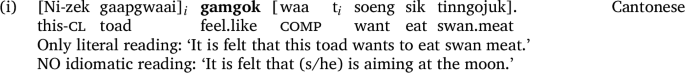

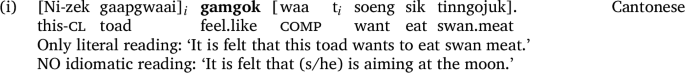

Second, sentential idioms retain their idiomatic reading in cases where their subject appears at a distance from the remnant in the embedded clause, as shown in (33). As widely assumed, an idiomatic chunk must form a constituent, either in the lexicon (Jackendoff 1997), or in a local domain in the course of derivation (Marantz 1997). The preservation of idiomatic meaning suggests that the subject originates as part of the idiom in the embedded clause.Footnote 12

The third piece of evidence concerns resumptive/co-referent pronouns. In topic constructions, base-generated topics (marked by the topic markers ne in Cantonese and thì in Vietnamese) can be co-referential with a base-generated pronoun, i.e. a resumptive pronoun, as shown in (34).

This is however not the case for RAV-constructions. The displaced subject cannot be co-referential with a pronoun in the embedded subject position, as shown in (35). We suggest that this is because the displaced subject is base generated in the embedded clause, but not in the matrix clause (cf. (34)), and thus the resumptive pronoun cannot occupy the same position.Footnote 13

The final piece of evidence concerns dou quantifier floating in Cantonese. Here, we assume with Chiu (1993), Hsieh (2005) that a universal quantifier in Chinese forms a constituent with the distributive operator dou (as DouP). In (36), dou may be “floated” in either the matrix or the embedded clause in RAV-constructions. The dou in the embedded clause indicates a residue of movement of the displaced subject from the embedded position.

Summing up, the above observations support the claim that displaced subjects in RAV-constructions undergo movement out of the embedded clause.Footnote 14 In the next subsection, we further argue that RAV-constructions involve A-movement.

3.2 A-movement, instead of A’-movement

It is important to determine whether the displaced subject has undergone A-movement (landing at Spec TP) or A’-movement (e.g., topic movement, landing at Spec TopicP/Spec CP). Provided that both Cantonese and Vietnamese are pro-drop languages, the latter option would suggest that the subject position is occupied by a null pro thematically selected by the matrix verb. This amounts to the suggestion that RAV-constructions are long-distance topic constructions. In the following, we provide three pieces of evidence against this “topic + pro” analysis, and show that the displaced subject has undergone A-movement (raising) but not A’-movement.

The first argument concerns the landing site of the movement. In Cantonese and Vietnamese, some quantifier phrases such as [many NP] and [how many NP] cannot serve as a topic, but can serve as a subject, as indicated by their incompatibility with topic markers in (37).

Crucially, these quantifier phrases can appear as the displaced subjects in RAV-constructions in (38). This suggests that the position before RAVs is a subject/A-position, instead of a topic/A’-position.Footnote 15

Another argument concerns the launching site of the movement. We observe that there is a subject-object asymmetry in RAV-constructions. The movement under discussion privileges subjects over objects, as illustrated in Vietnamese in (39), where the subject, but not the object, can move to the matrix clause. This is also observed in Cantonese ditransitive constructions in (40), where the movement privileges the subject over the direct object and the indirect object.

The subject-object asymmetry follows from the locality condition of A-movement (i.e., minimality), as the subject is a closer target than the object. Movement of the object over the subject is disallowed. Importantly, the subject-object asymmetry distinguishes RAV-constructions from topic constructions, where no similar asymmetry is observed.

The third argument concerns the interpretive effects of the subject movement: it creates new binding possibilities. As exemplified in (41), the universal quantified subject after movement can bind a pronoun that it cannot previously bind at the base position, showing a typical property of A-movement (Postal 1971; Wasow 1972). Notably, the quantifier has moved across a co-indexing pronominal variable but no weak crossover (WCO) effects are induced, in contrast with A’-movement (Postal 1971; see also Fong 2019 for a similar argument in Mongolian hyperraising). A’-movement constructions such as topicalization in both languages are subject to crossover effects (both strong and weak) and no new binding possibilities may be created (see Yip and Ahenkorah 2023 for Cantonese and Dao 2021, 200 for Vietnamese; see also Cheung 2009; Lee 2017 for Cantonese right-dislocation).

The same point can be illustrated with reflexive binding in (42), where the displaced subject can only bind a reflexive in the matrix clause after movement from the embedded clause.

That subject movement creates new binding possibilities on pronouns in (41) and on anaphors in (42) indicates that the displaced subject in RAV-constructions has undergone A-movement into the matrix clause, but not A’-movement (e.g., topicalization).

3.3 Movement out of a (finite) CP

Last but not least, we argue that the size of complement clauses in RAV-constructions is at least (finite) CP. The proposed (A-)movement thus crosses a CP boundary, instantiating a genuine case of hyperraising. This argues against a restructuring analysis where the embedded clauses are reduced to a smaller size such as v/VP (cf. Wurmbrand 2001; Cinque 2006; see the end of this section for a contrasting case). Below, we present arguments to build up the size of the embedded clauses from AspP to TP, then to finite TP, and finally to (finite) CP.

First, the embedded clauses in RAV-constructions can accommodate aspectual elements, such as the perfective marker -zo in Cantonese and the anterior marker đã in Vietnamese with an embedded scopal interpretation, as illustrated in (43). Other aspectual markers, such as Cantonese progressive -gan and experiential -gwo may also occur in RAV-constructions (see examples like (10b) and footnote 7). Hence, the embedded clauses are larger than v/VP, as least AspP.

Second, the embedded clauses in RAV-constructions may have distinct temporal specification from the matrix clauses, as in (44). This indicates that embedded clauses are at least as large as TP to accommodate tense elements.

Third, while temporal specification may not necessarily indicate finiteness of T (as an anonymous reviewer points out), the embedded clauses in RAV-constructions can accommodate elements that only occur in finite clauses in both Cantonese and Vietnamese. Duffield (2017) argues that the above-mentioned anterior marker đã and the future marker sẽ in Vietnamese are only allowed in finite clauses and locate at T (or move from Asp to T for đã). As shown in (44b) above and (45) (reproduced from (6f)) below, the embedded clauses in RAV-constructions allow đã and sẽ respectively, showing that they are finite clauses (i.e. at least finite TPs).Footnote 16

Zhang (2019) argues that temporal SFPs (like le and laizhe) are the locus of finiteness in Mandarin Chinese. Cantonese also has a similar set of SFPs whose distribution is restricted to finite clauses, like laa3 (perfect) and lai4 (recent past) (Tang 1998). Notably, they can be embedded in RAV-constructions such as (46), supporting the finite status of the embedded T.Footnote 17

Fourth, the presence of complementizers in RAV-constructions indicate that the embedded clauses are CPs. As already shown in many of the above examples, the embedded clauses may have an optional, overt complementizer waa in Cantonese and rằng/là in Vietnamese. They are arguably C heads (for Cantonese, see Yeung 2006; Huang 2021, 2022; for Vietnamese, see Chappell 2008). It is therefore natural to consider the size of embedded clauses a full finite CP.

An additional piece of evidence comes from selection on clause types. Some attitude verbs like ‘(not-)know’ and ‘(not-)remember’ may take declarative clauses and interrogative clauses, as illustrated by the different complementizers rằng/là ([-Q]) and liệu ([+Q]) in (47a) in Vietnamese. However, RAV-constructions can only be formed with an embedded interrogative clause (but not a declarative clause), as shown in (47b). This contrast demonstrates that RAV-constructions are sensitive to clause types. Assuming that the distinction of clause types indicates the presence of a CP projection, the complement clauses of RAVs are CPs.

This point is further supported by the ability of the embedded clause in RAV-constructions to host a topic or a focus, such as a base-generated topic in (48a) or an ex-situ focus in (48b). Under the assumption that elements in the left periphery indicate the presence of a CP (or a phase edge in phase-theoretic terms), (48) provides additional support to the presence of a CP boundary.Footnote 18

Finally, the embedded clauses in RAV-constructions are large enough to have their own illocutionary domain and may accommodate speaker-oriented adverbs that are high on the clausal spine (cf. Cinque 1999). As illustrated in Cantonese in (49), the embedded clauses allow mirative ‘surprisingly’ and evaluatlve ‘unfortunately.’ Following Huang (2022), we take encoding of illocutionary information, along with the temporal information mentioned above, as evidence for finiteness.

To sum up this section, we have shown that displaced subjects in RAV-constructions are derived by A-movement across a finite CP boundary, instantiating a case of hyperraising.

Before we move on to our analysis, an anonymous reviewer raised concerns that not all raising structures are connected to evidentiality. For example, in Cantonese, predicates like hoici ‘begin,’ hou jungji ‘be easy’ as well as middle constructions with the inchoative suffix heilei allow subject raising but do not necessarily encode an evidential component. It should be, however, remarked that it is not the purpose of the paper to link all raising cases in Cantonese and Vietnamese to evidentiality. Instead, we argue that only hyperraising cases (i.e. raising out of CP) are related to evidentiality. It follows that raising cases that are not “hyper” (e.g. raising out of TP/vP) need not be connected to evidentiality. That the predicates under discussion do not involve hyperraising is evidenced by the observation that the embedded clauses of these predicates do not allow (i) embedded focus, (ii) speaker-oriented adverbs, and (iii) distinct temporal specifications. They are thus plausibly restructuring predicates and take a smaller clause than CP (e.g. TP/vP).

4 The proposal

Taking stock, we have obtained two important observations in Cantonese and Vietnamese. The first one is the Subject-Evidentiality Correlation, discussed in Sect. 2.2, repeated in (51) from (17):

The second observation discussed in Sect. 3 is that RAV-constructions instantiate cases of hyperraising, where the embedded subject A-moves to the matrix subject position from within the embedded clause, crossing a CP boundary. Combining two observations, hyperraising is restricted to a certain type of attitude verbs that require indirect evidentiality. In Sect. 4.1, we detail our proposal to capture how hyperraising is selectively allowed for attitude verbs that encode an indirect evidential component. An illustration of the proposal is given in Sect. 4.2. In Sect. 4.3, we argue against two alternative analyses to a phase deactivation account.

4.1 A phase deactivation account

Our proposal is couched under the phase-theoretic minimalist framework, where a CP constitutes a phase (Chomsky 2000, et seq.). There are two ingredients in our proposal. First, we propose a pair of syntactic features that are responsible for marking indirect evidence, namely, the interpretable [iEVindirect] feature, and its uninterpretable counterpart [uEVindirect].Footnote 19 The latter must be checked before Transfer to interfaces for LF convergence. In Cantonese and Vietnamese, the RAVs bear [uEVindirect], whereas their CP complements bear [iEVindirect], indicating that the denoted proposition is based on indirect evidence. We stress that only RAVs, but not NRAVs, carry the uninterpretable feature, as illustrated in Table 5.

Secondly, and crucially, we suggest that the phasehood of a CP can be deactivated by a prior Agree relation between the attitude verb and the CP. In effect, when a RAV selects and Agrees with its CP complement, it at the same time deactivates the phasehood of the CP. Consequently, the RAV can further probe into the embedded CP, and Agree (for a second time) with the embedded subject. The embedded subject is then able to move to the matrix clause in one fell swoop. Schematically, the proposal is represented in (52a). Note that the CP would be otherwise opaque in the absence of such Agree relation with the attitude verbs (i.e., if it is selected by NRAVs), as shown in (52b).

The suggestion to connect Agree to the suspension of locality requirements has its precedents in Richards (1998), Rackowski and Richards (2005), among others. Nunes (2008), Halpert (2016, 2019) specifically apply the idea to hyperraising constructions. All these proposals share the idea that a CP is “opened up” by a prior Agree relation. Our proposal slightly differs from them in terms of what triggers the first Agree relation. In our case of Cantonese and Vietnamese, it is an evidential feature, instead of a categorial feature or a phi-feature.Footnote 20

For concreteness, we suggest that the inventory of C heads in the two languages is as shown in Table 6. We suggest that in Cantonese the C heads (waa, or its null counterpart) are phonetically indistinguishable by its featural makeup—it sounds the same regardless of whether it possesses an evidential feature or whether it comes with a clause type feature does not. On the other hand, in Vietnamese, while the two declarative C heads are also phonetically indistinguishable, the interrogative C head bearing the evidential feature takes a different form.Footnote 21

4.2 An illustration

We illustrate the proposal step by step with the Cantonese example in (1a), partially repeated in (53).

First, the complement CP ‘the rain will not stop’ is built. The C head waa bears the [iEV] feature and percolates to the CP projection. Under Phase Theory (Chomsky 2000), it constitutes a phase, and is opaque to subsequent syntactic operations (indicated by the solid line frame).

Then, the matrix verb gamgok ‘feel like’ selects this CP as its complement. As proposed, gamgok encodes [uEV] and agrees with the CP to check the [uEV] feature. Crucially, this Agree relation “opens up”/“unlocks” the CP, i.e., the CP phasehood is deactivated with respect to the V head (indicated by the dash frame).Footnote 22

Subsequently, the v head bearing a [D] feature combines with the structure and triggers V-v movement.Footnote 23 The complex head gamgok+v inherits the properties of V head. As a result, the CP that is “transparent” with respect to V is now also “transparent” to v (following the Principle of Minimal Compliance). The [D] on v can thus further probe down into the CP and attract the embedded DP subject to satisfy its [D] feature.Footnote 24 The subject is then allowed to move across the CP boundary (to Spec vP).Footnote 25 The derivation continues with a further movement of the subject to Spec TP for another [D] feature on T (not shown in the diagram).

Notably, if the embedding verb is a NRAV, the subject movement in (56) is disallowed due to the absence of a prior Agree relation. In such case, if the subject moves in one fell swoop, it violates the locality requirement imposed by the CP phase (i.e. Phase Impenetrability Condition, Chomsky 2000, 2001). Alternatively, if it takes Spec CP, an A’-position, as an intermediate landing site, it cannot subsequently land at a matrix A-position. Otherwise, this would constitute a case of Improper Movement (Chomsky 1973; May 1979), resulting in unacceptability.

4.3 Alternative analyses

In this subsection, we compare and contrast the proposed phase deactivation account with other existing analyses on hyperraising constructions. We show that existing analyses do not adequately capture the empirical properties of the hyperraising constructions in Cantonese and Vietnamese.

Before we start, it is instructive to give a brief overview on existing analyses on hyperraising. The major task in the discussion of hyperraising concerns how to capture the contrast between hyperraising-disallowing languages like English (Chomsky 1973; May 1979) and hyperraising-allowing languages like Cantonese and Vietnamese (and many other languages).Footnote 26 A standard approach to rule out hyperraising structures in English, for example, involves the conspiracy of two components in (57).

Existing proposals on hyperraising can be divided into two main families:

While our proposed phase deactivation account belongs to the first family, it is best characterized as a dynamic approach, where CPs might lose their phasehood during syntactic derivations (Nunes 2008; Halpert 2016, 2019). Such an account contrasts with other static approaches, where some CPs are inherently non-phasal (i.e. defective) (Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou 1999; Uchibori 2000; Zeller 2006; Ferreira 2009). Section 4.3.1 further discusses the differences between these two approaches. Furthermore, our account also differs from the second family in terms of movement steps: we suggest that hyperraising in Cantonese and Vietnamese involves one movement step instead of multiple steps. We discuss this issue in Sect. 4.3.2.Footnote 27

4.3.1 “Defective” CPs that do not impose locality requirements

The gist of a defective CP approach to hyperraising constructions is that it differentiates defective CPs from non-defective CPs by making reference to the featural definition of the embedded T heads. A T head is said to be “defective” if it lacks certain phi-features (Chomsky 2000, 2001, 2005). This idea has been adopted by Ferreira (2009) to account for hyerraising constructions in Brazilian Portuguese. He proposes that finite Ts may bear an incomplete set of phi-features and thus exceptionally allow subject movement out of a finite CP. Other proposals along this line extend the notion of defectiveness to include tense features as well (Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou 1999; Uchibori 2000; Zeller 2006). These proposals suggest that a CP can be defective if it lacks a tense feature, which differentiates subjunctive complements and non-finite CPs from indicative complements and (ordinary) finite CPs. Crucially, as suggested in Uchibori (2000), if a T head is defective, the C head that embeds it constitutes a weak phase, instead of a strong one. In effect, the locality requirement of defective CPs would then be different from that of non-defective CPs, schematically represented in (59).

Since the embedded clauses in Cantonese and Vietnamese hyperraising constructions are finite and tensed (see Sect. 3.3), applying this approach to both languages requires expanding the notion of “defectiveness” to evidential features, in addition to phi-features and tense features.Footnote 28 A conceivable formulation is to suggest that a CP with an indirect evidential feature constitutes a weak phase, whereas a CP without such a feature is a strong phase.

There are however two challenges to this approach. The first one is conceptual. It is unclear why evidential features form a natural class with phi-features and tense features. While the latter two have a clearer association with T heads, the former does not. More importantly, a defective CP approach faces an empirical challenge. Under this approach, the phasehood of a CP is determined by the properties of the CP. It does not make reference to the embedding verbs. We predict that as long as the CP comes with an indirect evidential feature, hyperraising should be allowed regardless of the embedding attitude verbs. However, this prediction is not borne out. Recall that attitude verbs like jingwai/nghĩ ‘think’ are underspecified for direct or indirect evidence, and thus they are compatible with an indirect-evidence-based complement. Accordingly, it is expected that these verbs may allow hyperraising in indirect contexts. Yet, this is not the case, as illustrated in (60) (see also (18b)).

The unacceptability of (60) indicates that an indirect-evidence-based complement is only necessary but not sufficient in licensing hyperraising. In addition to the properties of CP, the choice of attitude verbs must also be taken into consideration. Note that a variant of a defective CP approach might suggest that the difference in locality requirements between clauses is reflected on their syntactic size. For example, a clause with an indirect evidential feature might be syntactically smaller than one without the indirect evidential feature. As such, it might be that the former does not constitute a phase whereas the latter does. However, this is subject to a similar challenge given (60), if we exclude the role of attitude verbs in accounting for hyperraising constructions.

On the other hand, under our phase deactivation account, these issues do not arise. Instead of positing a general distinction in phasehood on CPs (i.e., indirect/defective CPs vs. direct/non-defective CPs), we suggest that attitude verbs differ in terms of feature encoding. In our cases of Cantonese and Vietnamese, the indirect evidential component on RAVs is realized as a syntactic feature that triggers an Agree relation with the CP. Crucially, this feature is responsible for phase deactivation as proposed. As such, in (60), while the clausal complement bears an (interpretable) indirect evidential feature, the attitude verb does not bear the uninterpretable counterpart. No Agree relation is established, and the locality requirement is in effect. This explains why (60) is unacceptable.

4.3.2 Successive A-movement and the featural definition of Spec CP

Another alternative to hyperraising constructions suggests that the movement steps involved in hyperraising can be a legitimate successive cyclic A-movement via Spec CP. This is achieved by reformulating the A/A’-nature of the Spec CP position. Following Chomsky (2007, 2008), the A/A’-distinction relies on the featural specification of the head. If the C head has A-features (in addition to A’-features, i.e., it is a composite Probe, van Urk 2015), its specifier is also an A-position. If so, A-movement via Spec CP to the matrix clause would not constitute Improper Movement. The movement chain is now a proper A-A-A chain, rather than an “improper” A-A’-A chain. This approach has been adopted to explain hyperraising in Japanese, Lusaamia (Bantu), Mongolian, and other languages (Bruening and Rackowski 2001; Tanaka 2002; Takeuchi 2010; Obata and Epstein 2011; Fong 2019; Wurmbrand 2019).Footnote 29

An implementation of this approach to Cantonese and Vietnamese requires us to posit a link between the evidential features and A-features through lexical selection. A verb endowed with an evidential feature would need to select a CP that has A-features, in order to ensure that the moving subject can take Spec CP (an A-position) as an intermediate landing site. In contrast, a verb without an evidential feature obligatorily selects a CP that has only A’-features, whose specifier is an A’-position and thus disallows hyperraising.

This approach, however, faces a number of challenges. First, conceptually, the link between evidential features and A-features appears to be stipulative. It is unclear why A-features are dependent on a specific type of A’-features syntactically, or how evidentiality is related to A-positions or the grammatical functions of arguments. The sensitivity of hyperraising to evidentiality in both Cantonese and Vietnamese (and other languages to be discussed in Sect. 5) suggests that the link cannot be reduced to some language-specific property either.

Second, empirically, there is no evidence that hyperraising of subjects in Cantonese and Vietnamese proceeds via Spec CP. For example, the displaced subject cannot be pronounced in the intermediate Spec CP, as shown in (62). Note that this is possible in Mongolian hyperraising constructions discussed in Fong (2019), and is taken as evidence for a successive A-movement approach.

The same point can be illustrated with quantifier floating in Cantonese (see also discussions in Sect. 3.1). In (63), the quantifier dou can only float at the embedded subject position (i.e. Spec TP), but not at the embedded Spec CP.

Likewise, Vietnamese quantifier tất cả ‘all,’ as exemplified in (64a), shows a similar ban on floating at Spec CP. In (64b), the prenominal quantifier tất cả may float and be realized at the embedded subject position at Spec TP. In (64c), however, tất cả cannot be pronounced at the embedded Spec CP.

Additionally, evidence from reflexive binding shows that the subject movement in hyperraising constructions does not land at the Spec CP in the derivation. To set up the relevant configuration, we include a perspective adverbial, which is higher than the subject at Spec TP, as in (65).

The example in (66) shows that elements in Spec CP (e.g., a topic) can bind the reflexive keoizigei ‘himself/herself’ in the perspective adverbial.Footnote 30

Crucially, in the hyperraising case in (67), where a sentence with a perspective adverbial is embedded by the RAV tengman ‘hear,’ the binding relation between the matrix subject and the reflexive in the perspective adverbial is no longer possible. This points to the absence of a potential reconstruction position in the embedded Spec CP.

The unacceptability of (67), together with (62) and (63), shows that there is no intermediate position at Spec CP for hyperraising. The position is not available for pronunciation in the PF nor interpretation in the LF. This is unexpected if hyperraising of subjects is derived via a two-step movement passing through the Spec CP. We therefore conclude that hyperraising constructions in Cantonese and Vietnamese involve subject movement in one fell swoop, which is made possible under the proposed phase deactivation analysis.

5 Extension: The hyperraising-evidentiality connection

We extend our proposal to other languages in this section. In Sect. 5.1, we suggest that the connection between hyperraising constructions and evidentiality is not limited to Cantonese and Vietnamese, but also in other languages. This not only lends support to the proposed evidential feature that licenses hyperraising, but also highlights evidentiality as one important semantic dimension in hyperraising. In Sect. 5.2, we briefly discuss how languages that disallow hyperraising may be explained under the current proposal.

5.1 Cross-linguistic split in predicates allowing hyperraising

We show that many attested cases of hyperraising reveal an evidential split in a way similar to Cantonese and Vietnamese. We discuss Romanian in Sect. 5.1.1, and Spanish in Sect. 5.1.2. We further discuss the case in Tiriki (Bantu) in Sect. 5.1.3.

5.1.1 Hyperraising-to-object in Romanian

Similar to Cantonese and Vietnamese, Romanian shows a connection between evidentiality and hyperraising (to object) (Alboiu and Hill 2013a,b, 2016). Consider (68) and (69). The (a) sentences represent the baseline, where the embedded subject Mihai resides in the embedded clause. The (b) sentences show that the subject is moved out of the embedded clause and lands at the matrix object position (marked with differential object marking, i.e., pe Mihai). The embedded verb still agrees with Mihai after movement. Notably, Alboiu and Hill (2016, 261) observe that the movement of subject is possible “only in sentences with hearsay/inferential readings.” They also provide a list of verbs that allow hyperraising, including verbs of perception (=68) and verbs of knowledge (=69). These verbs come with indirect evidentiality in the hyperraising cases.

Importantly, Alboiu and Hill (2016) report that a similar alternation is not observed with other verbs, such as spus ‘say,’ crede ‘believe/think,’ and dovedeşte ‘prove,’ and these verbs do not seem to encode indirect evidence. We also observe that verbs with factivity like aminti ‘remember’ and regreta ‘regret’ and verbs that do not specify evidence types like gândi ‘think’ disallow hyperraising.Footnote 31 Two examples are given in (70).

The restrictions on both the choice of predicates and the potential interpretation with regard to (indirect) evidentiality in Romanian pattern with our case of Cantonese and Vietnamese. For concreteness, we propose the following feature specification on attitude verbs in Romanian (same as Cantonese and Vietnamese), as shown in Table 7.

Given this feature specification, our proposed deactivation account readily extends to capture the split among different attitude verbs and their connection with evidentiality in Romanian.Footnote 32

5.1.2 Hyperraising-to-object in Spanish

While all the cases we have seen so far show a correlation between hyperraising and indirect evidence, our last case in Spanish shows a slightly different pattern, where hyperraising is correlated with direct evidence.

Suñer (1978), Herbeck (2020) discuss alternating structures of the (a) sentences in (71) and (72), which involve a matrix perception verb with an object DP (as in the (b) sentences) or a clitic (as in the (c) sentences) and a subject-less inflected complement (subject position indicated by ∆).

Without going into details, we follow Herbeck (2020) and assume a subject movement analysis for the sentences in (b) and (c), where the subject moves across the embedded CP into the matrix clause. Provided that the indicative que-complement is a CP, this arguably instantiates a case of hyperraising to object.

Crucially, Suñer (1978), Herbeck (2020) argue that the relevant constructions are restricted with respect to direct perception. First, the movement is contingent on the type of evidence on which the complement clause is based. If the context disfavors a direct perception reading, the movement is disallowed, as illustrated by (73) with inferential evidence. The contrast in (73) suggests that the complement clause must be based on direct (perceptual) evidence for hyperraising to occur.

Second, the hyperraising constructions are incompatible with propositions that cannot be directly observed, such as one’s habit or one’s ability/obligation in (74).

Note that in the absence of hyperraising, the sentence with a perception verb is compatible with direct or indirect evidence (hence ambiguous, as indicated in the translation in (75)).

We therefore suggest that the case in Spanish is minimally different from the Cantonese and Vietnamese in terms of the featural specification on the embedding verbs, as shown in Table 8. The uninterpretable feature associated with attitude verbs that allow hyperraising is a direct feature, instead of an indirect feature. This means that perception verbs in Spanish are lexically ambiguous between RAVs and NRAVs, and the availability of subject movement is correlated with direct evidence.

5.1.3 Hyperraising-to-subject in Tiriki (Bantu)

We have seen that languages may vary in the types of evidential features that license hyperraising: while it is the indirect feature in Cantonese, Vietnamese and Romanian, it is the direct feature in Spanish. Indeed, both types of features can be found in one single language and similarly license hyperraising. This is attested in Tiriki (Luhya, Bantu) (Diercks et al. 2022).

To begin with, Tiriki has two expletive agreement markers on verbs, ka- (class 6) and i- (class 9). They are sensitive to the direct vs. indirect classification of evidentiality: ka- is only compatible with indirect evidence, whereas i- is only compatible with direct evidence. As shown in (76), where the context is an indirect (i.e., inferential) one, the matrix attitude verbs must be marked with ka-, but not i-.

In contrast, i-marked verbs are only allowed in contexts where the embedded proposition is based on direct evidence like the direct visual evidence in (77). Ka- is not compatible with the context in (77).

More importantly, both ka-marked verbs and i-marked verbs allow hyperraising, and, strikingly, they retain the same evidential restrictions. Hyperraising with ka-verbs is only licensed with indirect evidence, and hyperraising with i-marked verbs is only licensed with direct evidence. The patterns are exemplified in (78)–(79).Footnote 33

Incorporating these observations to our proposal, we suggest that Tiriki is a language that has both indirect evidential [uEVindirect] and direct evidential [uEVdirect] features on the verbs, exponed as ka- and i-, respectively (as shown in Table 9. Under our proposal, they crucially establish agreement relations with the clausal complement clauses that carry the corresponding evidential features, thus allowing hyperraising (to subjects).

Summing up, this subsection revealed that the connection between hyperraising and evidentiality is supported by cross-linguistic evidence. Languages may vary with regard to the type of evidential features that license hyperraising, and both [EVindirect] and [EVdirect] are attested. Under the current proposal, hyperraising in these languages is made possible since the phasehood of the CP complement is deactivated by the Agree relation in evidential features between the predicate and the complement clause.

5.2 Variations in evidential marking and hyperraising

Given that attitude verbs commonly encode evidentiality in natural language, and that, as we propose, hyperraising is correlated with evidentiality, this seems to predict that hyperraising would be available in general. However, many languages disallow hyperraising, such as English and German.

To explain why not all languages allow hyperraising under the current proposal, we suggest that hyperraising is not licensed by the semantic/lexical evidential component, but by the Agree relation established between elements that possess the syntactic evidential features. If a language lacks syntactic evidential features on attitude verbs, no Agree relation can be established between the verbs and the CP complement clauses. The CP phasehood would remain intact, and subject movement would be impossible from within the CP complement due to locality requirements. We suggest that this is why languages like English disallow hyperraising.Footnote 34

We briefly discuss a piece of suggestive evidence for this suggestion. The claim that English lacks syntactic evidential features on attitude verbs can be linked to the absence of grammatical evidential marking in English. In English evidentiality is marked via lexical means, including adverbials such as reportedly and allegedly, and parentheticals such as I think.

On the other hand, as we have already seen, the evidential marking is grammatically marked on verbs in Tiriki, and hyperraising is allowed. Although the evidential features on attitude verbs in Cantonese and Vietnamese are phonologically null, their presence may find support from the presence of other grammatical marking of evidentiality in both languages. For example, in Cantonese, the sentence-final particle (SFP) wo5 marks hearsay evidence (Leung 2005; Sybesma and Li 2007; Tang 2015). It is often accompanied with the hearsay attitude verb tenggong ‘hear,’ as shown in (81).

In the evidential system proposed in Tang (2015), there are also SFPs that mark unexpectedness (wo4) and obviousness (lo1). Lee (2021) also argues that lo1 is a grammatical evidential marker. Likewise, in Vietnamese, SFPs such as rồi, express indirect grammatical evidentiality (Dao 2021).

We take the presence of evidentiality-related SFPs as a piece of suggestive evidence for the grammaticalization/syntactization of the evidential component in Cantonese and Vietnamese. The proposed null evidential features belong to a larger grammatical system of evidential marking in these languages.Footnote 35

6 Conclusions

In this paper, we first revealed a correlation between the position of subjects and evidentiality in (83), repeated from (3).

We then showed that subjects embedded under RAVs undergo A-movement to the matrix clause across a finite CP boundary, instantiating a hyperraising configuration. To connect hyperraising to evidentiality, we proposed a phase deactivation account, where the phasehood of a CP is deactivated by an Agree relation between the attitude verb and the CP complement. This Agree relation is achieved by an indirect evidential feature.

The findings of this paper reinforce the dynamic nature of phasehood, which may interact with other operations during the syntactic derivation. In other words, phasehood is not set once and for all. This is in line with recent proposals on phase deactivation (Rackowski and Richards 2005; Nunes 2008; Halpert 2016, 2019; Branan 2018; den Dikken 2018; Branan and Davis 2019; Toquero-Pérez 2021; Carstens 2023b,a), and more generally, the malleable nature of locality constraints (den Dikken 2006; Gallego and Uriagereka 2006; Gallego 2010; Stepanov 2012; Bošković 2014; Pesetsky 2021).

Another implication of the current proposal is that there may be a non-idiosyncratic distribution of hyperraising predicates. The strong correlation between evidence types and hyperraising in Cantonese, Vietnamese and other languages indicates that the distribution of hyperraising predicates across languages follows a semantic dimension, i.e., evidentiality. This provides a partial explanation for a cross-linguistic tendency observed in Lohninger et al. (2022) that predicates participated in cross-clausal A-dependencies involve knowledge, belief and perception. Existing proposals also suggest that there may be other semantic dimensions of hyperraising. For example, topicality may play a role in Turkish (Şener 2007), and predicative properties potentially affect the possibility of hyperraising in Korean and Japanese (Yoon 2007; Horn 2008). Wurmbrand (2019) also points out that the raising possibility of English predicates is linked to their thematic configuration. We leave further investigation into the semantic dimensions of (hyper)raising phenomena to future research.

Notes

We use the term “hyperraising” (HR) to refer to a specific type of A-movement where an embedded subject moves across a CP to the matrix clause. Depending on the landing site of the embedded subject, HR can be subdivided into HR-to-Subject (HRtS) and HR-to-Object (HRtO). See Ura (1994) for an early comprehensive cross-linguistic study. The following serves as an overview on hyperraising-allowing languages reported in the literature:

Abbreviations that are not in the Leipzig Glossing Rules: accomp=accomplishment marker; ant=anterior marker, cl=classifier; exp=experiential aspect; incho=inchoative aspect, mod=modification marker; sfp=sentence-final particle.

Cantonese examples are transcribed in Jyutping (the Linguistic Society of Hong Kong Cantonese Romanization Scheme, 1993), and tones (1–6) are represented when necessary. Vietnamese examples are transcribed in Vietnamese alphabets. The Cantonese and Vietnamese data in this paper are collected from the Internet, interviews with native speakers (during 2019–2023, for Vietnamese), and introspection by the two authors (for Cantonese). The judgment is confirmed by nine native speakers of Hong Kong Cantonese (including the two authors) and five native speakers of Hanoi/Northern Vietnamese.

We do not discuss the more regular, transitive usage of attitude verbs in this paper.

These hyperraising cases, to the best of our knowledge, have not been systematically studied in Cantonese and Vietnamese, nor in Mandarin Chinese, where similar patterns of subject displacement are also found:

Note that these cases are different from the Mandarin cases reported in Ura (1994), which involves epistemic modals (rather than genuine raising verbs); and those in Chen (2022), which involves passives. See footnote 7 and Chen (2023) for an interesting connection between hyperraising and passivization.

Examples (6b, 6e, 6f) are elicited from native speakers of Vietnamese. The rest of the data are taken from the Internet, with the source url links and access dates listed below: (5a) https://forum.hkgolden.com/thread/7502278/page/2, accessed on January 30, 2022; (5b) https://www.hkepc.com/forum/viewthread.php?fid=20&tid=2448986&extra=page% 3D6&page=4, accessed on January 30, 2022; (5c) https://www.discuss.com.hk/viewthread.php?tid=29616035, accessed on May 10, 2021; (5d) https://zh-yue.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%87%B7%E7%96%91, accessed on May 10, 2021; (5e) https://neard.com/feeds/146968, accessed on May 10, 2021; (5f) https://lihkg.com/thread/2722456/page/36, accessed on January 30, 2022; (5g) https://hk.sports.yahoo.com/news/%E9%BB%9E%E8%A7%A3%E9%A6%AC%E6%96%AF%E5%85%8B%E6%9C%AA%E6%9C%89-cosplayer-072317130.html, accessed on May 10, 2021; (5h) https://diary.showhappy.net/?id=76768&page=26, accessed on January 30, 2022; (5i) https://medium.com/econ%E8%A8%98%E8%80%85/5g-plan-%E8%AC%9B%E7%B7%8A%E5%B9%BE%E5%A4%9A%E9%8C%A2-d203f51d73bf, accessed on May 10, 2021; (6a) https://truyenfull.vn/sieu-viet-thang-cap-he-thong/chuong-395/, accessed on September 20, 2021; (6c) https://www.quansuvn.net/index.php?topic=41.435;wap2, accessed on September 20, 2021; (6d) https://books.google.com/books?id=33NbuReW5PYC&pg=PA166&lpg=PA166&dq= %22n%C3%A0y+nghi+l%C3%A0%22&source=bl&ots=5Yv1RGhg7R&sig=ACfU3U1S6YJ gQdAUkn7C0n9jWWu-IFsPtw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjv-9yu0I7zAhUGVN8KHXT9AkE Q6AF6BAgIEAM#v=onepage&q=%22n%C3%A0y%20nghi%20l%C3%A0%22&f=false, accessed on September 20, 2021; (6g) https://www.otofun.net/threads/thanh-ly-giay-da-that-moi-tinh.1753941/, accessed on January 30, 2022; (6h) https://baodautu.vn/tai-tu-sat-gai-o-hollywood-so-rang-da-truyen-hiv-cho-hang-loat-nguoi-tinh-cu-d35395.html, accessed on September 20, 2021.

With the exception of ‘suspect’ and ‘believe,’ all the RAVs, despite having transitive usages, cannot be passivized, unlike NRAVs. Yet, as will be seen in the next subsection, evidentiality captures the split between RAVs and NRAVs better than argument structure. Intriguingly, though, passivized NRAVs may allow long-distance passive movement of the embedded subjects, constituting another type of hyperraising (see Chen 2022 for Mandarin). See Chen (2023) for an interesting idea that hyperraising is “general” for all the attitude verbs, namely RAVs and passivized NRAVs.

One difference between RAVs and epistemic modals is that epistemic modals impose a stricter requirement on the choice of indirect evidence: they require inferential evidence, but not reportative evidence (von Fintel and Gillies 2010). We do not attempt an explanation.

As correctly pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, the indirect evidential component should not be equated with “speakers’ uncertainty,” since verbs like hangding in Cantonese and chắc chắn in Vietnamese express speakers’ certainty, but they allow subject displacement. Thus, subject displacement is correlated with the indirect evidence component, rather than an uncertainty component. This also suggests that certainty, or the strength of belief, is not necessarily correlated with evidence type. As argued by von Fintel and Gillies (2010), strong necessity modals like must also encode an indirect evidence. In other words, one can be certain about a proposition not only based on direct but also indirect evidence.

Although the NRAVs teng-dou and nghe-được are not formed by directly suffixing RAVs tengman and nghe nói, they still share the morpheme ‘hear’ (teng in Cantonese and nghe in Vietnamese). The same goes for cảm-thấy ‘feel-accomp’ and cảm giác ‘feel like.’

For independent reasons, not all RAVs may take these verbal suffixes, so we do not have (near-)minimal pairs for each RAV.

The idiomatic reading should not be conflated with a metaphoric reading. This is because replacing the subject with a synonym does not give rise to the idiomatic reading, like gaapgwaai ‘toad’ in Cantonese below.

The incompatibility with resumptive pronouns also distinguishes RAV-constructions from copy-raising constructions, where an embedded resumptive pronoun establishes an A-chain with a matrix subject, e.g., Richardi seems like hei is in trouble in English (Potsdam and Runner 2001).

The evidence presented here also rules out a finite control alternative, where a base-generated matrix subject is (obligatorily) coreferent with an embedded null pro (= [Si RAV [CP proi V O]). Additionally, RAVs pattern with ordinary raising predicates in preserving truth conditions under passivization as in (i), unlike control predicates.

.

This test is adopted from Ferreira (2009) in his discussion on hyperraising in Brazilian Portuguese.

The finiteness of the embedded clauses in RAV-constructions also speaks against a defective CP approach to hyperraising, as we will discuss in Sect. 4.3.

These SFPs are in the embedded rather than matrix clause, as evidenced by the following two tests. First, the temporal contribution by the SFPs (perfect/recent past) applies to the embedded predicate ‘fell down’ rather than the matrix one in (46). Such scope is made explicit by the corresponding adverb zingwaa ‘just now’ in the embedded clause, which, as argued by Tang (2009), Cheng (2015), forms a clause-bounded discontinuous construction with the SFP lai4. Second, when the embedded clause is displaced, these SFPs must also be displaced together (as shown below with a transitive use of tengman ‘hear’), indicating that they form a constituent with the embedded clause.

.

An anonymous reviewer notes that this assumption, while reasonable, is not guaranteed. For example, Zubizarreta (1998, Chap. 3) argues that in certain variety of Spanish, overt leftward focus movement and wh-movement targets Spec TP, rather a Spec position in the CP domain. Supporting evidence comes from the observation that these elements compete with the preverbal subject for a single position. To the best of our knowledge, base generated topic or focus elements do not share this property in Cantonese and Vietnamese, but we are grateful to the reviewer’s suggestion bringing our attention to this possibility.

There is a non-trivial conceptual question as to why an Agree relation may affect locality requirement. As with many other proposals, we suggest that this follows from the Principle of Minimal Compliance (PMC), as proposed in Richards (1998).

The idea is that locality requirement on the attitude verbs is satisfied once by the first Agree dependency with the clausal complement. The attitude verbs are then immune to the same locality requirement in their second Agree relation. With regard to the conceptual motivation behind this idea, we agree with Richards (1998, 597) in that PMC represents “a general property of human language that constraints need not be satisfied perfectly in all parts of a given structure for that structure to be well formed.”

As correctly pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, the proposed inventory of C heads potentially increases the lexical costs of the current proposal. We, however, maintain that a lexicalist approach to the Subject-Evidentiality Correlation established in Sect. 2 is superior to an approach that directly links the hyperraising of the subject (as also hinted at by the same reviewer) to some semantic distinction. Under standard assumptions on the modularity of the computational system, it would require fairly non-standard assumptions to implement how the semantic distinction could be reflected on the locality condition of subject movement. Acknowledging that potential lexical concerns on the proposed inventory, we argue that the Subject-Evidentiality Correlation is better handled by introducing the mediation of Cs that bear an evidential feature, which requires no modification on standard architectural assumptions.

The current proposal does not predict that the CP is transparent for all syntactic operations. It is just “unlocked” for the Probe of the first Agree relation (i.e., RAVs)—it is relativized to the respective head which agrees with the phasal CP. For example, long-distance passiviation, whose application is only limited to crossing non-finite clausal boundaries (and blocked by finite clasual boundaries, Huang 2022), cannot apply across the embedded CP in RAV-constructions:

The phasal CP in RAV-constructions also blocks agreement. Yip (2022) argues that the universal concord element -can agrees with a universal quantifier such as mui-ci ‘every time,’ and the agreement is (finite) clause-bounded. Crucially, -can cannot be embedded in RAV-constructions, showing that the CP from which the subject is hyperraised is still a phase for other operations.

Conceptually, as discussed in footnote 21, the mechanism of phase unlocking, as with many other proposals, is based on the Principle of Minimal Compliance (Richards 1998), the spirit of which is to avoid multiple application of the same (locality) constraint on an element (hence minimal compliance). Put differently, whether a domain is transparent or not depends on its probe. In our analysis, while the CP (of RAVs) is transparent to its probe, it does not necessarily mean that it is so to other probes (if any).

The [D] feature may be an EPP or a case feature that is responsible for subject movement. We do not distinguish these features here.

Using the same quantifier floating test discussed in Sect. 3.1, we see that the distributive operator dou can be “floated” at a position lower than the temporal adverb but above the verb, i.e., the Spec vP position. This indicates the intermediate position of the hyperraised subject.

See the languages cited in footnote 1.

While we stress the limitations of existing alternative analyses when applied to Cantonese and Vietnamese, we do not argue that all cases of hyperraising should fall under the current phase deactivation account; instead, there may be more than one way to derive hyperraising constructions. Given the diversity of empirical properties displayed by hyperraising constructions in different languages, it is no surprise that hyperraising is a non-uniform phenomenon.

Note also that Cantonese and Vietnamese do not have morphological inflection of phi-features.

There are two variants of the successive movement approach. For Alboiu and Hill (2016), hyperraising in Romanian is indeed A’-movement (with mixed A-properties) driven by an A’-feature on the matrix v. The movement proceeds via the embedded Spec CP as standard A’-movement. The A-properties of hyperraising are due to the A-features on the composite v Probe. Another variant is a Horizon-based approach by Kobayashi (2020), following Keine (2019, 2020). For Kobayashi, an A-A’-A chain is allowed in Brazilian Portuguese hyperraising. Despite differences in terms of implementations, these approaches share the core idea that the Spec CP position is an intermediate landing cite of cross-clausal A movement. We do not further distinguish these approaches.

Cross-linguistically, bare reflexives may involve logophoric licensing and participate in long-distance binding, whereas compound reflexives may not and must be locally bound, as widely attested in Icelandic, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Mandarin Chinese, etc. (Cole and Sung 1994; Huang and Liu 2001). The same is true for Cantonese zigei ‘self’ vs. keoizigei ‘3sg.self’ (Matthews and Yip 2011).

We thank our five Romanian consultants for the judgment.

As pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, hyperraising in Romanian, unlike Cantonese and Vietnamese, has an additional constraint: it is blocked by embedded topic/focus (Nunes 2008, 94 fn. 9; see also Grosu and Horvath 1987; Dobrovie-Sorin 1994). Moreover, hyperraising in Romanian is also incompatible with long-distance wh-movement (Alboiu and Hill 2016). The incompatibility between hyperraising and A’-movement (topic/focus/wh-movement) is reminiscent of the idea of composite A’/A probes suggested in Obata and Epstein (2011), van Urk (2015). C heads in languages like Kilega and Dinka carries both [A’]/[A] features, and triggers mixed A’/A-movement that conflicts with (pure) A’-movement since both move to/via Spec CP. This explanation is adopted by Alboiu and Hill (2016) to account for the Romanian data, where the hyperraised DP moves via the embedded Spec CP headed by a composite C probe. This idea is further pursued in Lohninger et al. (2022), Lohninger and Yip (2023) to account for a set of languages where hyperraising disallows additional A’-movement, including Romanian, Japanese, Korean, Tsez, and Turkish. Strikingly, this set of languages also imposes a semantic restriction on the hyperraised DPs (e.g., topic/focus/evidential source), which is attributable to the interpretation of the [A’] feature in the mixed A’/A movement. On the other hand, Cantonese and Vietnamese impose no semantic restrictions on the hyperraised DPs (but instead on the matrix verbs, as we propose). This provides a plausible explanation on why A’-movement does not block hyperraising in these languages, unlike Romanian. We would also like to note that the intermediate movement to Spec CP in Romanian does not void the need of the phase deactivation account, since Romanian also exhibits the evidential restrictions on the verbs in a way similar to Cantonese and Vietnamese. See also van Urk and Richards (2015), Carstens (2023b) for a view that languages like Dinka or Xhosa require both movement to phasal edge and phase deactivation for extraction.

This does not mean that languages without grammatical evidentiality cannot have hyperraising. As discussed in Sect. 4.3, languages with A-features on the C head may also allow hyperraising in a successive cyclic fashion, such as Mongolian (Fong 2019). Other languages may achieve phase deactivation for hyperraising via phi-features, such as Zulu (Halpert 2019).

As critically pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, it is crucial to provide evidence for the syntactic nature of the proposed evidential features associated with SFPs. Possible syntactic realizations of the syntactic evidential feature may take form of morphological agreement (double marking), locality conditions, and feature intervention, among others. It is, however, not immediately clear to us whether there is evidence from Cantonese and Vietnamese illustrating these points, due to the general lack of inflection in these languages. To the best of our knowledge, proposals specifically addressing the syntactic nature of evidential features are limited. We are aware that in Quechua evidential features can be doubly marked on both C and T, lending support to the syntactic nature of evidential feature (Sánchez 2004). We thank the reviewer for raising the careful question relating to the nature of evidential features.

References

Alboiu, Gabriela, and Virginia Hill. 2013a. A-bar movement with Case effects: Indirect evidentiality in Romanian. Handout of talk given at Concordia Univeristy, Montreal.

Alboiu, Gabriela, and Virginia Hill. 2013b. On Romanian perception verbs and evidential syntax. Revue Roumaine de Linguistique 58(3): 275–298.

Alboiu, Gabriela, and Virginia Hill. 2016. Evidentiality and raising to object as A’-movement: A Romanian case study. Syntax 19(3): 256–285.

Alexiadou, Artemis, and Elena Anagnostopoulou. 1999. EPP without Spec,IP. In Specifiers, eds. David Adger, Bernadette Plunkett, George Tsoulas and Susan Pintzuk, 93–109. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bošković, Željko. 2014. Now I’m a phase, now I’m not a phase: On the variability of phases with extraction and ellipsis. Linguistic Inquiry 45(1): 27–89.

Branan, Kenyon. 2018. Attraction at a distance: Ā-movement and case. Linguistic Inquiry 49(3): 409–440. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling_a_00278.

Branan, Kenyon, and Colin Davis. 2019. Agreement and unlocking at the edge. Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America 4(1): 16. https://doi.org/10.3765/plsa.v4i1.4512.

Bruening, Benjamin, and Andrea Rackowski. 2001. Configurationality and object shift in Algonquian. In Proceedings of British Columbia Working Papers in Linguistics, eds. Suzanne Gessner, Sunyoung Oh and Kayono Shiobara, Vol. 5, 71–84.

Carstens, Vicki. 2023a. Addressee agreement and clitic-raising in Kiunguja Swahili: Unlocking &P. In Angles of object agreement, eds. Andrew Nevins, Anita Peti-Stantic, Mark de Vos and Jana Willer-Gold, 56–83. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carstens, Vicki. 2023b. Extraction and the syntax of Xhosa nominal expressions. Ms., University of Connecticut.

Carstens, Vicki, and Michael Diercks. 2013. Parameterizing case and activity: Hyper-raising in Bantu. In Proceedings of the 40th North East linguistic society, eds. Seda Kan, Moore-Cantwell Claire, and Robert Staubs, 99–115. Amherst: GLSA.

Chan, Sheila Shu-Laam, Tommy Tsz-Ming Lee, and Ka-Fai Yip. 2022. Discontinuous predicates as partial deletion in Cantonese. In UPenn working papers in linguistics, Vol. 28.

Chappell, Hilary. 2008. Variation in the grammaticalization of complementizers from verba dicendi in Sinitic languages. Linguistic Typology 12: 45–98. https://doi.org/10.1515/LITY.2008.032.

Chen, Fulang. 2022. Three anti long-distance dependency effects in the Mandarin BEI-construction. In Proceedings of the Chicago linguistic society (CLS57).

Chen, Fulang. 2023. Obscured universality in Mandarin, PhD thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Cheng, Siu Pong. 2015. The relationship of syntactic and semantic aspects of postverbal particles and their preverbal counterparts in Hong Kong Cantonese, PhD thesis, the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Cheung, Lawrence Yam-Leung. 2009. Dislocation focus construction in Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 18(3): 197–232.

Chiu, Bonnie Hui-Chun. 1993. The inflectional structure of Mandarin Chinese, PhD thesis, University of California, Los Angeles.

Chomsky, Noam. 1973. Conditions on transformations. In A festschrift for Morris Halle, eds. Stephen Anderson and Paul Kiparsky, 232–286. New York: Holt Rinehart and Winston.

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In Step by step: Essays on minimalist syntax in honor of Howard Lasnik, eds. Roger Martin, David Michaels, and Juan Uriagereka, 89–156. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2005. Three factors in language design. Linguistic Inquiry 36(1): 1–22.

Chomsky, Noam. 2007. Approaching UG from below. In Interfaces + recursion = language?, eds. Uli Sauerland and Hans-martin Gärtner, 1–29. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Chomsky, Noam. 2008. On phases. In Foundational issues in linguistic theory: Essays in honor of Jean-Roger Vergnaud, eds. Robert Freidin, Carlos Otero, and Maria Luisa Zubizarreta, 133–166. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1999. Adverbs and functional heads: A cross-linguistic perspective. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 2006. “Restructuring” and functional structure. In Restructuring and functional heads, ed. Guglielmo Cinque. Vol. 4 of Cinque, the cartography of syntactic structures, 11–64. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cole, Peter, and Li-May Sung. 1994. Head movement and long-distance reflexives. Linguistic Inquiry 25(4): 335–406.

Dao, Huy Linh. 2021. Vietnamese expletive between grammatical subject and subjectivity marker. In Studies at the grammar-discourse interface: Discourse markers and discourse-related grammatical phenomen, eds. Alexander Haselow and Sylvie Hancil, 195–228. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

den Dikken, Marcel. 2006. Relators and linkers. Cambridge: MIT Press.

den Dikken, Marcel. 2018. Dependency and directionality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Diercks, Michael, Cliff Mountjoy Venning, and Kristen Hernandez. 2022. Agreeing and non-agreeing hyper-raising in Luyia: Establishing the empirical landscape. Ms., Pomona College.

Dobrovie-Sorin, Carmen. 1994. The syntax of Romanian. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Duffield, Nigel. 2017. On what projects in Vietnamese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 26(4): 351–387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-017-9161-1.