Abstract

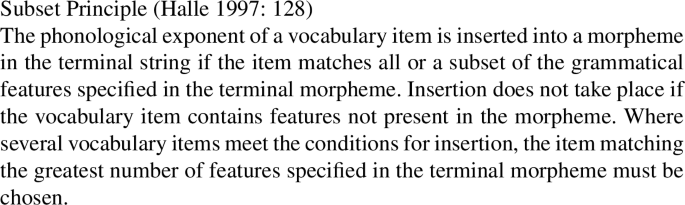

In this paper, I argue that declension classes are not primitives (see Aronoff 1994; Alexiadou 2004; Kramer 2015; i.a.), but are decomposed into simpler features, one of which is gender (Harris 1991; Wiese 2004; Caha 2019). The argument is based on semantic gender agreement in Russian, where a grammatically masculine noun can trigger feminine agreement if its referent is female (Mučnik 1971; Pesetsky 2013). Semantic agreement is grammatical only in those forms where a regular nominal exponent is syncretic with an exponent of a declension class that includes feminine nouns. In other forms, conflicting masculine and feminine gender features lead to ineffability in morphology (cf. Schütze 2003; Asarina 2011; Coon and Keine 2020). Ineffability arises because the Subset Principle (Halle 1997) that holds between features of a vocabulary item and a terminal at the point of Vocabulary Insertion is violated later in the derivation. This is in turn possible if Vocabulary Insertion applying cyclically bottom-up (Bobaljik 2000) is interleaved with Lowering that alters structure below a triggering node (Embick and Noyer 2001). Finally, I show that Russian also has a number of cases where conflicting gender features in a noun phrase do not result in a realization failure (Iomdin 1980). The difference between these patterns is derived in a principled way and follows from the positions where conflicting features are introduced.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In some languages the shape of nominal inflection is determined not only by features like number and case, but also by the declension class of a noun. A declension class can be defined as a group of nouns taking the same set of inflectional exponents (see Aronoff 1994). Class membership often correlates with gender, but there is no one-to-one correspondence between them. For instance, Russian has 3 genders and 4 declension classes (see Karcevskij 1932; Corbett 1982; Timberlake 2004). Gender specifications cannot be fully deduced from declension class membership. All class  nouns are feminine, but class

nouns are feminine, but class  includes both feminine and masculine nouns. Similarly, gender is insufficient to predict class. While all neuter nouns belong to class

includes both feminine and masculine nouns. Similarly, gender is insufficient to predict class. While all neuter nouns belong to class  , feminine nouns are distributed over classes

, feminine nouns are distributed over classes  and

and  . Apart from that, class membership and gender are relevant for different processes in a language: class determines nominal inflection, while agreement targets gender.

. Apart from that, class membership and gender are relevant for different processes in a language: class determines nominal inflection, while agreement targets gender.

In this paper, I address the connection between declension class and gender: what derives correlation, but not one-to-one correspondence between them? The existing literature provides several possible answers. According to the first, declension classes are formed from bundles of features, one of which is gender (see Roca 1989; Harris 1991; Wiese 2004; Wunderlich 2004; Caha 2019, 2021). Gender can be accompanied by phonological or formal features of a lexeme. Inflectional exponents traditionally viewed as expressing declension class then in fact realize gender combined with other features of nominal stems. According to the second answer, class exponents do not bear gender features and the relation between declension and gender is captured only indirectly, for instance by implicational redundancy rules. Under this view, there are either separate features corresponding to declension classes (as in Corbett 1982, 1991; Ralli 2000; Alexiadou 2004; Kramer 2015; Arsenijević 2021; Gouskova and Bobaljik 2022) or class is decomposed into features not related to gender (see Müller 2004; Alexiadou and Müller 2008). Finally, some approaches give the major role in forming declensions to separate class features but allow individual exponents to refer to gender in a very limited number of cases (see Halle 1992, 1994; Aronoff 1994; Halle and Vaux 1998; Calabrese 2008; Kučerová 2018).

So far, the choice between these models has been made on the basis of such conceptual merits as elegance of a resulting model. In this paper, I present an empirical argument for the first position, using novel data on semantic gender agreement in Russian.Footnote 1 I will show that semantic agreement is subject to case number restrictions: it is grammatical only in some cells of the paradigm. The restriction is due to the inability to insert nominal exponents in the presence of an additional [+fem] feature. It indicates that insertion of nominal inflection targets gender features. Since gender alone is insufficient to determine declension classes, I suggest that declensions arise from the combination of gender ([±fem]) and an idiosyncratic feature of a nominal stem ([±α]).

I will argue that the inability to insert a nominal exponent in some forms is a case of morphological ineffability: the morphological component fails to realize a structure supplied from the syntax. Under semantic gender agreement, a problem for realization arises from the conflict between grammatical and semantic gender, which can be resolved only if a form is syncretic and underspecified for gender. This phenomenon thus contributes to an already substantial body of evidence showing that features with conflicting values can result in a realization failure (see Groos and van Riemsdijk 1981; Zaenen and Karttunen 1984; Schütze 2003; Citko 2005; Dalrymple et al. 2009; Asarina 2011; Bhatt and Walkow 2013; Bjorkman 2016; Hein and Murphy 2019; Coon and Keine 2020; among others).

At the same time, Vocabulary Insertion governed by the Subset Principle (Halle 1997), as is widely assumed in Distributed Morphology (see Halle and Marantz 1993, 1994; Harley and Noyer 1999; Siddiqi 2010), cannot fail due the presence of an additional feature independently of whether this new feature contradicts other features in the node. In case no vocabulary item matches all features in the node, insertion resorts to an exponent that matches a subset of the features. I propose that ineffability is derived as follows. First, Vocabulary Insertion applies to n, where case, number, grammatical gender, and [±α] are gathered, and inserts a nominal inflectional exponent. Second, semantic gender that is introduced higher in the nominal structure, but by virtue of belonging to the noun must be also incorporated in its feature structure, lowers into n. If the lowered feature is more marked, it overwrites existing features, e.g., [+fem] replaces [−fem]. If the inserted vocabulary item is specified for such features, the subset relation between its features and features of the node into which it was inserted does not hold anymore. This leads to a crash.

Thus, ineffability is due to the violation of the Subset Principle, which not only underlies Vocabulary Insertion, but is essentially a well-formedness constraint that must hold throughout the derivation; see, e.g., Arregi and Nevins (2012) on inviolable constraints in Distributed Morphology. The Subset Principle can be violated if features of a node are changed after Vocabulary Insertion has applied. This turns out to be possible in a model where Vocabulary Insertion that applies cyclically bottom-up coexists with the Lowering operation that alters features on the node below the trigger node. In contrast to the standard model where all morphological structure rules precede Vocabulary Insertion (Halle and Marantz 1993), I suggest that Vocabulary Insertion can be interleaved with Lowering; for other instances of interleaving Vocabulary Insertion with morphological operations, see Noyer (1992), Halle (1997), and González-Poot and McGinnis (2006) on Fission; Chung (2009) on Fusion; see also Dobler et al. (2011) and Piggott and Travis (2017) on interleaving Vocabulary Insertion and head movement.

According to this analysis, a contradictory feature will not lead to a realization failure if it is introduced lower in the structure and is incorporated into a node before Vocabulary Insertion. I will show that such derivations are attested in Russian with class  animate masculine nouns that have a conflict between masculine features triggering agreement in syntax and feminine gender realized by morphology, as well as with so-called common gender nouns.

animate masculine nouns that have a conflict between masculine features triggering agreement in syntax and feminine gender realized by morphology, as well as with so-called common gender nouns.

I will start by introducing semantic gender agreement in Russian and the case number restrictions on it in Sect. 2. Section 3 argues that gender is part of the decomposition of declension classes, and then decomposes the Russian declensions accordingly. In Sect. 4, I turn to morphological ineffability. Section 5 presents the analysis of the core data and Sect. 6 derives cases where conflicting features do not lead to a crash. I discuss implications of the analysis in Sect. 7.

2 Semantic gender agreement in Russian

2.1 Basics

In Russian, some profession-denoting nouns are grammatically masculine but allow for feminine agreement if the referent is female (see Panov 1968; Mučnik 1971; Skoblikova 1971; Crockett 1976; Graudina et al. 1976; Corbett 1991; Gerasimova 2019). Vrač ‘doctor’ is one such noun. In (1a), it indicates a female individual and can trigger attributive agreement either for its grammatical masculine gender or for its semantic feminine gender.Footnote 2 Example (1b) shows that both grammatical and semantic agreement are also possible on the predicate.Footnote 3

-

(1)

In (2), two probes agreeing with the same noun bear distinct gender values and give rise to mixed agreement.

-

(2)

The set of masculine nouns that allow for feminine semantic agreement is naturally limited to nouns that have referents of different genders, but no separate form that could be used without negative connotations for female referents. Among this already fairly restricted group of nouns, feminine semantic agreement is widely attested and productive.Footnote 4

All analyses of feminine agreement with grammatically masculine nouns agree that there is an additional feminine gender feature in the noun phrase, but differ with respect to where this feature is introduced. It may be on a dedicated functional projection (see Asarina 2009; Pesetsky 2013), on ϕP (see Sauerland 2004), on the D head (see Pereltsvaig 2006; Steriopolo and Wiltschko 2010; King 2015; Lyutikova 2015; Steriopolo 2019), on the Num head (see Landau 2016), on the noun (as in Smith 2015, 2017; Puškar 2017, 2018; Salzmann 2020), or on a nominal modifier directly (see Matushansky 2013; Caha 2019). The higher position of the feminine gender adopted in some of these approaches is motivated by height restrictions. First, feminine semantic agreement is impossible with low classifying adjectives:

-

(3)

Second, while the switch from masculine agreement on lower modifiers to feminine agreement on higher probes is (somewhat marginally) allowed, the reverse switch from feminine to masculine agreement is ruled out; cf. (4a) vs. (4b).

-

(4)

For now I will abstract away from the height restrictions (see references above for possible analyses) and will introduce a different type of restriction on semantic gender agreement in Russian—the case number restrictions.

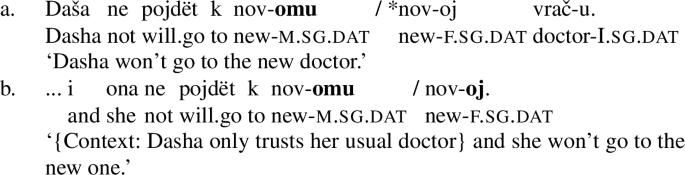

2.2 Case number restrictions

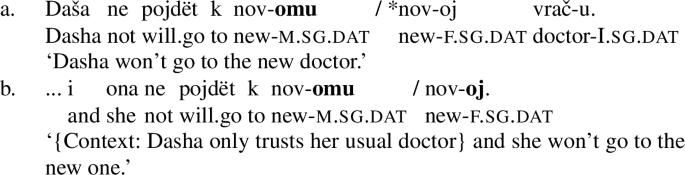

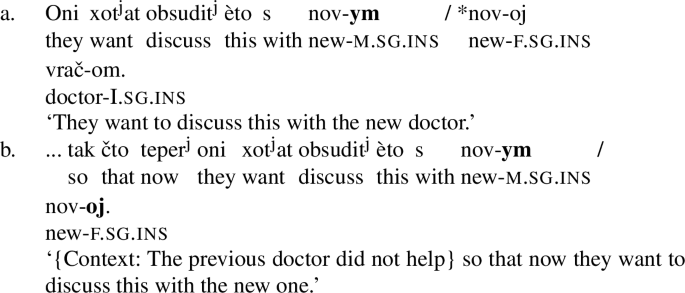

Russian has six basic cases and two numbers, i.e., there are twelve cells in the nominal paradigm. Only a few of these forms allow for semantic feminine agreement with grammatically masculine nouns. As shown in examples above, feminine agreement is possible in the nominative singular; see also example (5).

-

(5)

Feminine agreement is ruled out if the noun is singular and has any case other than nominative. Examples in (6) show ungrammaticality of feminine agreement with a singular noun in the accusative, genitive, dative, locative, and instrumental case forms.

-

(6)

Gender agreement in Russian is, as a rule, restricted to the singular; that is, if a noun is plural, agreement on its modifiers realizes number and case but not gender. This is shown in (7), where a modifier agreeing with a masculine noun stol ‘table’ and with a feminine noun dver ‘door’ has exponents differing in gender in the singular, but the same exponent is used in the plural.

‘door’ has exponents differing in gender in the singular, but the same exponent is used in the plural.

-

(7)

One exception to the absence of gender agreement in the plural is the modifier ob-a/e ‘both-m/f.’ It shows gender distinctions after agreement with a plural noun. Gender is marked by a vowel that precedes regular case and number exponents:

-

(8)

As observed by Pesetsky (2013), ‘both’ agrees in semantic feminine gender with a plural noun marked for cases other than nominative:

-

(9)

The availability of feminine agreement in the nominative plural form cannot be tested: if the noun phrase is in the nominative position, ‘both’ is marked for nominative, while the noun is in a form that for vrač ‘doctor,’ as well as for a majority of Russian nouns, is homophones with the genitive singular; see (10).

-

(10)

Despite the similarity with the genitive singular, the marking on the noun in (10) is often viewed as a separate form because for a number of nouns it differs from the genitive singular in its stress pattern (see Zaliznjak 2002). Also, adjectives modifying it show genitive plural, not genitive singular agreement; see (11).

-

(11)

All in all, the nature of this form is one of the widely discussed puzzles in Russian numeral constructions (see Babby 1987; Franks 1994; Pesetsky 2013; Ionin and Matushansky 2018; i.a.). Apart from ‘both,’ the form appears with a group of small numerals—paucals. This group includes two further modifiers that mark gender distinctions: dv-a/e ‘two-m/f’ and poltor-a/y ‘one.and.a.half-m/f.’

-

(12)

Unlike ob- ‘both,’ dv- ‘two’ and poltor- ‘one.and.a.half’ mark gender distinctions only in the nominative. As for ob- ‘both,’ feminine agreement with profession-denoting grammatically masculine nouns is ungrammatical in this form; see (13).

-

(13)

Not all modifiers that require the paucal form show gender distinctions; for instance, tri ‘three’ and četyre ‘four’ do not mark gender. Modifiers that show gender agreement with non-singular nouns, at least in some of their forms—‘both,’ ‘two,’ ‘one and a half’—can then be unified as having a dual meaning (see Ionin and Matushansky 2018: 180), and one might further hypothesize that gender agreement in Russian is in fact possible only with a dual but not with a plural noun. The hypothesis presupposes that Russian factually distinguishes between three numbers: singular, dual, and plural. This is not supported empirically: first, Russian does not have special dual inflection. The paucal form discussed earlier cannot be viewed as such, because its distribution is broader than that of dual modifiers. Second, gender and number can be realized in parallel only by exponents on the dual modifiers, but not on other modifiers (e.g., adjectives) in the same noun phrase. Realization of gender together with the plural also does not occur if the noun phrase just has dual meaning but the relevant modifiers are missing.

I conclude that despite a severely restricted set of modifiers that can show gender agreement with a plural noun, agreement on ‘both’ shows that gender agreement with a plural noun is in principle possible. Plural nouns thus must have gender features, but they are not realized morphologically in the presence of a plural number feature. Realization of both gender and number turns out to be possible on dual modifiers due to their inherent number features (see Sect. 5.4 for a formal analysis).

To sum up, this section has introduced case number restriction on semantic feminine agreement with grammatically masculine nouns in Russian. The data show that feminine agreement is possible in the nominative singular and in non-nominative plural forms.

2.3 Previous accounts of case number restrictions

Case number restrictions are mentioned in the literature (see Pereltsvaig 2006; Matushansky 2013; Gerasimova 2019; Pesetsky 2013) and there are some attempts to account for them.

According to King (2015), feminine gender is introduced in the D head that is present in the nominative but absent in other cases. Thus, the ungrammaticality of feminine agreement in oblique cases is due to the lack of the projection that can bear feminine gender. The underlying assumption about the distribution of the DP layer is however not supported empirically. Furthermore, since semantic agreement is possible with oblique cases in the plural, this analysis does not account for the data.

According to Pesetsky (2013), feminine gender is introduced in a functional projection above the noun and some of its modifiers. Gender probes that are higher in the structure then target this gender instead of the one on the noun. This derives the possibility of semantic feminine agreement. Feminine agreement can be ungrammatical for one of two reasons: the inability to realize [+fem] on class  nouns or the inability of a modifier to get the feminine feature. In the first case, the feminine feature appears on the noun because the case-assigning heads V, N, and P probe for gender and then assign it to the noun together with case. In the singular, the feminine feature on class

nouns or the inability of a modifier to get the feminine feature. In the first case, the feminine feature appears on the noun because the case-assigning heads V, N, and P probe for gender and then assign it to the noun together with case. In the singular, the feminine feature on class  nouns like vrač ‘doctor’ results in a realization failure. This explains the ungrammaticality of feminine agreement in (6). In the plural, the feminine gender does not lead to a crash (see (9)) because all nouns are assigned to class

nouns like vrač ‘doctor’ results in a realization failure. This explains the ungrammaticality of feminine agreement in (6). In the plural, the feminine gender does not lead to a crash (see (9)) because all nouns are assigned to class  , so that inflection realizing [+fem] is available. As for the nominative singular, where feminine agreement is allowed as well (see (5)), the noun does not receive the feminine feature: the D head that assigns nominative does not probe for gender and does not assign it to the noun. In the second case, modifiers do not show feminine agreement because they cannot access the feminine feature. This causes ungrammaticality in (10), where ob-a ‘both-m’ is in the nominative and the noun is marked for genitive. Pesetsky suggests that ‘both’ is merged lower than the feminine gender feature, so it agrees with the noun and gets masculine. Next, it head-moves to D, which has no gender to assign. Note that the incompatibility between feminine gender and class

, so that inflection realizing [+fem] is available. As for the nominative singular, where feminine agreement is allowed as well (see (5)), the noun does not receive the feminine feature: the D head that assigns nominative does not probe for gender and does not assign it to the noun. In the second case, modifiers do not show feminine agreement because they cannot access the feminine feature. This causes ungrammaticality in (10), where ob-a ‘both-m’ is in the nominative and the noun is marked for genitive. Pesetsky suggests that ‘both’ is merged lower than the feminine gender feature, so it agrees with the noun and gets masculine. Next, it head-moves to D, which has no gender to assign. Note that the incompatibility between feminine gender and class  declension cannot derive this example because the noun does not receive the feminine feature. It shows genitive, which under Pesetsky’s approach is the intrinsic case that surfaces in the absence of a case assigner. This means that there is no higher head that assigns case and could introduce the feminine gender here.

declension cannot derive this example because the noun does not receive the feminine feature. It shows genitive, which under Pesetsky’s approach is the intrinsic case that surfaces in the absence of a case assigner. This means that there is no higher head that assigns case and could introduce the feminine gender here.

This analysis shares with the account that I will develop the idea that the unacceptability of the feminine agreement on a modifier can arise due to a morphological conflict on a noun. However, in Pesetsky’s analysis, morphological properties are insufficient to derive the full set of data, and additional factors such as properties of the D head are employed. I would like to contend that this analysis misses a generalization about the distribution of feminine agreement. In fact, all ungrammatical examples are due to the conflict in morphology, and this conflict is resolved by a syncretic exponent in all contexts where feminine agreement is allowed. Moreover, in Pesetsky (2013), the incompatibility between the declension class of profession-denoting nouns that trigger semantic agreement and the feminine feature is assumed rather than derived.

Before turning to my account in Sects. 3 and 4, I will present two novel arguments showing that ungrammaticality stems from the inability to realize nominal inflection in morphology.

2.4 Syncretism

The first argument comes from the shape of nominal inflection. As mentioned above, Russian has 4 declension classes, and class membership often correlates with the gender of a noun. In particular, class  includes only grammatically masculine nouns. Class

includes only grammatically masculine nouns. Class  predominantly consists of feminine nouns but also includes a group of animate masculine nouns.Footnote 5 Class

predominantly consists of feminine nouns but also includes a group of animate masculine nouns.Footnote 5 Class  has feminine nouns, and class

has feminine nouns, and class  (labeled

(labeled  b by Timberlake 2004) consists of neuter nouns. The relation between gender and declension in Russian is summarized in (14).

b by Timberlake 2004) consists of neuter nouns. The relation between gender and declension in Russian is summarized in (14).

-

(14)

The table in (15) presents the nominal inflectional exponents in Russian. The table does not show regular phonological alternations. In the accusative and genitive plural of classes  and

and  , the choice between /ov/ and /ej/ is phonologically conditioned for nouns that end in a consonant that contrasts for palatalization. For all other nouns, the choice is subject to a set of idiosyncratic rules. Also, the exponents given in (15) are used by animate nouns. For them, accusative coincides with genitive in the singular of class

, the choice between /ov/ and /ej/ is phonologically conditioned for nouns that end in a consonant that contrasts for palatalization. For all other nouns, the choice is subject to a set of idiosyncratic rules. Also, the exponents given in (15) are used by animate nouns. For them, accusative coincides with genitive in the singular of class  and in the plural. Inanimate nouns take inflection identical to the nominative in these forms.Footnote 6

and in the plural. Inanimate nouns take inflection identical to the nominative in these forms.Footnote 6

-

(15)

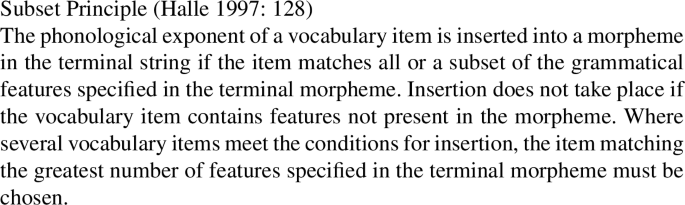

Profession-denoting nouns that trigger feminine agreement are, like all other nouns of class  , grammatically masculine. By going through the declensional exponents of Russian nouns, I will show that semantic gender agreement is grammatical if and only if a class

, grammatically masculine. By going through the declensional exponents of Russian nouns, I will show that semantic gender agreement is grammatical if and only if a class  exponent is syncretic to an exponent of a class that includes feminine nouns.

exponent is syncretic to an exponent of a class that includes feminine nouns.

In the singular, /ø/ is the nominative exponent in classes  and

and  . Note that although all nouns in class

. Note that although all nouns in class  end in a palatalized consonant, š, or ž in the nominative singular, palatalization is not a nominative singular exponent but a property of class

end in a palatalized consonant, š, or ž in the nominative singular, palatalization is not a nominative singular exponent but a property of class  stems. This can be shown by attaching suffixes that preserve the palatalization specification of the preceding consonant. The locative plural suffix /ax/ is one such affix.Footnote 7 Examples (16a–b) show that this affix retains the [±palatalized] feature of the final consonant of the root. In these examples, locative /ax/ is attached to class

stems. This can be shown by attaching suffixes that preserve the palatalization specification of the preceding consonant. The locative plural suffix /ax/ is one such affix.Footnote 7 Examples (16a–b) show that this affix retains the [±palatalized] feature of the final consonant of the root. In these examples, locative /ax/ is attached to class  nouns ending in a non-palatalized and in a palatalized consonant respectively. In both cases, the locative suffix does not affect the characteristics of the final consonant.

nouns ending in a non-palatalized and in a palatalized consonant respectively. In both cases, the locative suffix does not affect the characteristics of the final consonant.

-

(16)

The locative plural suffix /ax/ is attached in (17) to a class  noun, whose final consonant remains unchanged. This demonstrates that [+palatalized] is a feature of the root: where it the nominative singular marker, it would not occur before this suffix.Footnote 8

noun, whose final consonant remains unchanged. This demonstrates that [+palatalized] is a feature of the root: where it the nominative singular marker, it would not occur before this suffix.Footnote 8

-

(17)

As a result, the third class nominative singular inflection is /ø/, and it is syncretic to the corresponding exponent in class  . In the singular, exponents of the locative case are also segmentally identical in classes

. In the singular, exponents of the locative case are also segmentally identical in classes  and

and  . They differ however in accentual properties: the class

. They differ however in accentual properties: the class  exponent is underlyingly stressed, while the class

exponent is underlyingly stressed, while the class  exponent is not; see Melvold (1989: 21), and also Zaliznjak (2010: 141) for the same contrast between these two exponents in Old RussianFootnote 9, and Müller (2004), which analyzes them as distinct vocabulary entries on the basis of independent conceptual considerations. Note that the underlying stress on the class

exponent is not; see Melvold (1989: 21), and also Zaliznjak (2010: 141) for the same contrast between these two exponents in Old RussianFootnote 9, and Müller (2004), which analyzes them as distinct vocabulary entries on the basis of independent conceptual considerations. Note that the underlying stress on the class  exponent and its absence on the exponent of class

exponent and its absence on the exponent of class  does not imply that the former affix is always stressed while the later never bears accent. It means that if these affixes are attached to stems with the same accentual characteristics, a resulting stress pattern will differ in some cases. Due to these suprasegmental differences, I conclude that the class

does not imply that the former affix is always stressed while the later never bears accent. It means that if these affixes are attached to stems with the same accentual characteristics, a resulting stress pattern will differ in some cases. Due to these suprasegmental differences, I conclude that the class  locative exponent is not syncretic to the exponent of class

locative exponent is not syncretic to the exponent of class  .

.

Consequently, in the singular, the nominative is the only form where an exponent of class  is syncretic to an exponent from a declension class that contains feminine nouns, and this is also the only form where semantic feminine agreement is grammatical.

is syncretic to an exponent from a declension class that contains feminine nouns, and this is also the only form where semantic feminine agreement is grammatical.

In the plural, class  exponents are identical to class

exponents are identical to class  exponents in the accusative and genitive. Plural inflection also does not differentiate between classes in the locative, dative, and instrumental. Thus, in the plural, class

exponents in the accusative and genitive. Plural inflection also does not differentiate between classes in the locative, dative, and instrumental. Thus, in the plural, class  inflection is syncretic with the inflection of at least one class with feminine nouns in all non-nominative forms, and as shown in Sect. 2.2, semantic agreement is grammatical in all these forms. As for the nominative plural from, exponents from classes

inflection is syncretic with the inflection of at least one class with feminine nouns in all non-nominative forms, and as shown in Sect. 2.2, semantic agreement is grammatical in all these forms. As for the nominative plural from, exponents from classes  ,

,  , and

, and  are identical, so that semantic agreement is expected to be possible here as well. These data are however not available, due to quirks in the syntax of the Russian noun phrase; see (10).

are identical, so that semantic agreement is expected to be possible here as well. These data are however not available, due to quirks in the syntax of the Russian noun phrase; see (10).

To sum up, all nouns that can trigger feminine agreement are grammatically masculine and belong to declension class  , which includes only masculine nouns. Feminine agreement is restricted to forms where exponents of this class are syncretic to exponents of class

, which includes only masculine nouns. Feminine agreement is restricted to forms where exponents of this class are syncretic to exponents of class  , which has feminine nouns. Thus, the grammaticality of feminine agreement on a modifier depends on nominal inflection. This dependency indicates that the restrictions are due to the inflection on a noun.

, which has feminine nouns. Thus, the grammaticality of feminine agreement on a modifier depends on nominal inflection. This dependency indicates that the restrictions are due to the inflection on a noun.

2.5 Ellipsis

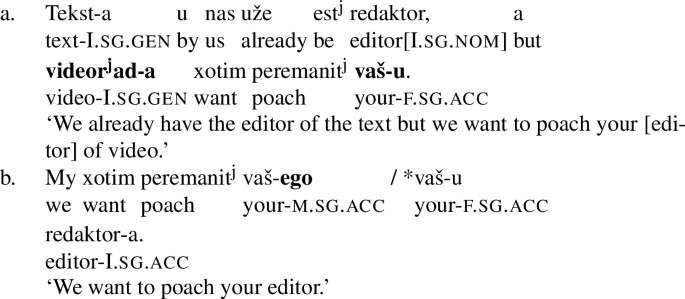

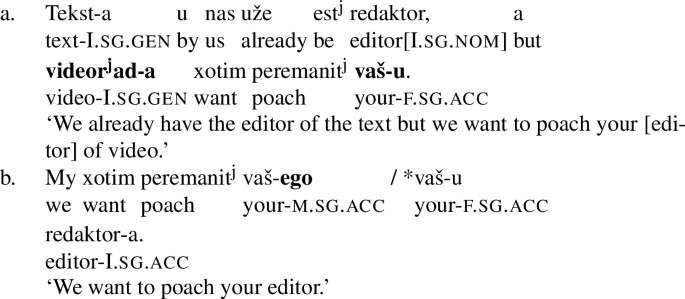

The conclusion from the previous section is further supported by nominal ellipsis data. As shown in the examples below, the case number restrictions do not hold if the noun is absent. Example (18) presents a minimal pair: in (18a), the noun is in the accusative singular form, and semantic feminine agreement is ungrammatical. In (18b), the noun is absent and feminine agreement is allowed.

-

(18)

The absence of the noun in (18b) is an instance of nominal ellipsis: the noun is present in the syntactic structure but not realized phonologically (see Merchant 2001; van Craenenbroeck and Merchant 2013; Saab 2019 on nominal ellipsis). Evidence for this comes from the data in (19)–(20). They show that the absent noun must be syntactically present for assignment of a Θ-role to its arguments as well as for idiosyncratic marking of its modifiers. The examples in (19) use the profession-denoting noun redaktor ‘editor.’ It can take an internal argument that indicates the object of editing. In (19a), this internal argument survives ellipsis of the noun by virtue of being focused and moving out of the ellipsis site. This shows that the phonologically absent noun can still assign a Θ-role to its argument and must therefore be present syntactically. The possessive modifier of the elided noun in (19a) shows feminine agreement.Footnote 10 Such agreement would be ungrammantical in the presence of the noun; compare (19b).

-

(19)

The example in (20a) demonstrates the availability of an idiosyncratic marking associated with the noun if it is elided. This example contains the profession-denoting noun repetitor ‘tutor.’ The modifier indicating the tutor’s specialization is introduced by the preposition po.

-

(20)

The preposition po can be used with various professions to indicate specialization, but its use is nevertheless restricted to a subset of hypothetically possible professions; compare (21) and (22). The preposition is thus idiosyncratically related to a number of nouns and its presence under ellipsis argues for the presence of the noun in the structure. As in the previous case, the adjective modifying an elided noun in (20a) allows for feminine agreement, while such agreement is ungrammatical if the noun is present as in (20b).

-

(21)

-

(22)

The assignment of a Θ-role and the idiosyncratic marking on a modifier shows that the syntactic structure of a noun phrase with ellipsis and one without it must be parallel. This argues against the analyses under which the absence of a noun is derived by nominalization of an adjective (see Bošković and Şener 2014) or by a null pronoun (see Lobeck 1995). The possibility of semantic feminine agreement with an elided noun, and the impossibility of it with a pronounced one, shows that it is the realization of the noun that leads to the ungrammaticality of feminine agreement.

The examples so far have illustrated the grammaticality of feminine agreement when the elided noun is in the accusative singular. Examples (23)–(26) present minimal pairs for other contexts where feminine semantic agreement is not acceptable in the presence of the noun and demonstrate that feminine agreement is grammatical under ellipsis; see (23) for the genitive singular, (24) for the dative, (25) for the locative, and (26) for the instrumental.

-

(23)

-

(24)

-

(25)

-

(26)

The examples in (27) show that ellipsis has no effect in cases where feminine agreement is grammatical in the presence of the noun. Example (27a) illustrates this for the nominative singular form, and (27b) for the accusative plural.

-

(27)

To sum up: the case number restrictions do not apply if a noun is elided, even though such nouns are syntactically present. It is therefore the Vocabulary insertion of the noun that leads to ungrammaticality.

3 Gender in declension

3.1 The argument

In this section, we move from the data to how they inform our understanding of declension classes and their relation to gender. Existing approaches (also discussed in Sect. 1) capture the correlation between class and gender in different ways. According to one view, gender is one of the features into which declension classes are decomposed, so that insertion of a nominal exponent that is traditionally considered class inflection in fact targets gender among other features (see Roca 1989; Harris 1991; Wiese 2004; Wunderlich 2004; Caha 2019, 2021). According to another view, declensions are either not decomposed, or decomposed into features other than gender (see Ralli 2000; Alexiadou 2004; Müller 2004; Alexiadou and Müller 2008; Kramer 2015; Gouskova and Bobaljik 2022). The relation between declension class and gender can be derived by implicational redundancy rules that supply class on the basis of gender or gender on the basis of class. Note that redundancy rules can also be used under the first view (see Roca 1989 and Harris 1991). The difference between the approaches is in whether redundancy rules are the only tool connecting gender and declension, and in whether other (formal or phonological) features are targeted by Vocabulary Insertion together with gender or instead of it. Another interesting perspective is offered by Arsenijević (2021), where in the spirit of Corbett (1982, 1991), it is argued that effects traditionally subsumed under the notion of gender can be derived from declension class and some semantic properties of nouns. Finally, some approaches that primarily rely on separate class features and essentially belong to the second type allow gender to participate in class inflection, but its usage is restricted to a few exponents (see Halle 1992, 1994; Aronoff 1994; Halle and Vaux 1998; Calabrese 2008; Kučerová 2018).

The views above make different predictions about what a change to gender features on a noun leads to. If exponents are specified for gender directly, altering the gender specification on a noun will immediately affect insertion of exponents in several forms, but crucially the change might not encompass all cells of the paradigm. It will not apply to exponents that are used with nouns of different genders and are therefore underspecified for it. Case number restrictions on semantic gender agreement in Russian display such an effect.

Under semantic gender agreement, a grammatically masculine noun has a female referent and triggers feminine agreement. Feminine agreement clearly indicates the presence of a feminine gender feature in a noun phrase, and there is a near consensus in the literature that this feature is introduced in the extended projection of a noun, so that it can act as a goal for probes on nominal modifiers (see Pereltsvaig 2006; Asarina 2009; Steriopolo and Wiltschko 2010; Pesetsky 2013; King 2015; Lyutikova 2015; Smith 2015, 2017; Steriopolo 2019). Thus, semantic agreement presents a case of change in the gender specifications of a noun—the feminine gender feature is added. The data in the previous section also show that semantic gender agreement gives rise to case number restrictions, i.e., it is acceptable only in some cells of a paradigm. Ungrammatical forms are due to the inability to insert an inflectional exponent, and grammatical forms are characterized by syncretism of exponents used with masculine class  nouns and feminine class

nouns and feminine class  nouns. These exponents are underspecified for gender.

nouns. These exponents are underspecified for gender.

Semantic gender agreement in Russian once again confirms the connection between declension class and gender: insertion of a nominal class exponent becomes impossible in the presence of an additional gender feature. Furthermore, case number restrictions on semantic gender agreement are what is predicted if class exponents are directly specified for gender: altering gender features results in ineffability unless exponents are underspecified for gender. This is because Vocabulary Insertion fails to provide an exponent for a node that contains contradictory features (masculine and feminine gender).

Let’s now turn to how the observed effect differs from the predictions made by approaches where class exponents are not specified for gender or the use of gender is radically restricted to a few exponents. The connection between gender and declension could be viewed as accidental, but this position is obviously falsified by case number restrictions, because the change in gender features affects class inflection. Alternatively, there could be implicational rules that connect declension and gender. If so, altering the gender specification of a noun could potentially lead to a change in a class feature that is supplied by a rule and targeted by Vocabulary Insertion, so that the change in gender results in differences in nominal inflection.

To identify how the change in inflection might look, I will examine some rules that have been used to connect gender and declension (see Halle 1990; Halle 1992, 1994; Aronoff 1994; Halle and Marantz 1994; Halle and Vaux 1998; Kramer 2015; Kučerová 2018; Gouskova and Bobaljik 2022). These are redundancy rules that were originally proposed in phonology (see, for instance, Jakobson and Halle 1956 and Chomsky and Halle 1968: 171). They supply a new feature on the basis of features that are already present, but cannot replace existing features or insert a second feature of a given type. At the same time, as rules of Vocabulary Insertion in Distributed Morphology (see Halle 1997), they apply according to specificity: if a context for more than one rule is met, only the more specific one applies. Thus, one noun will never have more than one class feature if class features are inserted by such redundancy rules.

I will exemplify these properties by redundancy rules that were suggested for Russian in Aronoff (1994). That work suggests a system with three classes; see (28). It differs from the one assumed here in that class  includes both masculine and neuter nouns. Differences in the inflection of masculine and neuter nouns are captured by the inclusion of both class and gender in the specifications of some affixes. Most realization rules are conditioned by the features

includes both masculine and neuter nouns. Differences in the inflection of masculine and neuter nouns are captured by the inclusion of both class and gender in the specifications of some affixes. Most realization rules are conditioned by the features  ,

,  , and

, and  , which directly correspond the three classes. The relation between declension and gender is derived by the three redundancy rules given in (29).

, which directly correspond the three classes. The relation between declension and gender is derived by the three redundancy rules given in (29).

-

(28)

-

(29)

The rule in (29a) applies to feminine nouns, the one in (29b) to all nouns. If a noun is feminine and does not have a class feature, the contexts for both rules are met, so that one might expect insertion of two declension class features, but in fact, only the class  feature—the more specific one—is inserted. Thus, specificity ensures that the rules in (29) never insert two class features simultaneously. The rules also do not apply if a class feature is prespecified. For instance, class

feature—the more specific one—is inserted. Thus, specificity ensures that the rules in (29) never insert two class features simultaneously. The rules also do not apply if a class feature is prespecified. For instance, class  nouns have a declension feature from the lexicon, and the rule in (29b) does not apply to them even though the context for its application is formally met.

nouns have a declension feature from the lexicon, and the rule in (29b) does not apply to them even though the context for its application is formally met.

The inability to supply two class features or alter an existing specification is by no means unique to the approach by Aronoff (1994). It is a defining property of class-filling redundancy rules used to relate gender and declension; among others see Halle and Vaux (1998: 224) for an elsewhere rule in Latin, and Kramer (2015: 239) for such a rule in Spanish. This inability to insert two class features defines what effect a change in gender might have on inflection in this type of approach.

There are two scenarios. In the first, an additional gender feature has no effect on the declension class feature. This will be the case, for instance, if a noun is prespecified for class or if the usual class is inserted because the redundancy rule that supplies it is more specific. Because nominal inflection only targets class features, which are not altered by changes to a noun’s gender, there will be no difference in inflection.

In the second, the class feature is inserted based on a new gender. Inflection from another declension will then be used throughout the paradigm, but there will be no source of ineffability in any cell of the paradigm.

To sum up, in approaches that only employ feature-filling redundancy rules to capture the connection between gender and declension class, an additional gender feature either does not lead to a change in inflection, or triggers insertion of different exponents in all forms. This differs from the case number restrictions arising in the presence of an additional gender feature in Russian, where the feature leads to ungrammaticality in some forms, but regular exponents are used in others.

Finally, for the sake of the argument, let’s assume that contrary to the nature of redundancy rules two class features are inserted. Since inflection under semantic gender agreement is impossible unless classes  and

and  are syncretic, the inserted class features must be

are syncretic, the inserted class features must be  and

and  .Footnote 11 To derive the data, conflicting class features must lead to a realization failure in forms where these classes require different inflection, and exponents syncretic between the two classes must be unspecified for class altogether to resolve the conflict.

.Footnote 11 To derive the data, conflicting class features must lead to a realization failure in forms where these classes require different inflection, and exponents syncretic between the two classes must be unspecified for class altogether to resolve the conflict.

The complete absence of class features in syncretic forms makes it impossible to derive forms where two or more declensions have the same inflection. For instance, classes  and

and  are syncretic in the accusative and genitive plural, as are classes

are syncretic in the accusative and genitive plural, as are classes  and

and  . Class

. Class  is also the same as class

is also the same as class  , and class

, and class  the same as class

the same as class  , in the genitive singular. If identical inflection is analyzed as true syncretism rooted in features, as is required for the syncretism between classes

, in the genitive singular. If identical inflection is analyzed as true syncretism rooted in features, as is required for the syncretism between classes  and

and  to account for case number restrictions, both the class

to account for case number restrictions, both the class  /

/ exponent and the class

exponent and the class  /

/ exponent must be unspecified for class. But then, the distribution between them cannot be derived. Thus, assumptions that are required to account for resolution by syncretism under semantic gender agreement make it impossible to account for the distribution of nominal exponents in general.

exponent must be unspecified for class. But then, the distribution between them cannot be derived. Thus, assumptions that are required to account for resolution by syncretism under semantic gender agreement make it impossible to account for the distribution of nominal exponents in general.

This further indicates that approaches employing primitive class features are poorly equipped to capture transparadigmatic syncretism, i.e., syncretism between declension classes. For such approaches, one could assume that all instances of transparadigmatic syncretism are in fact accidental homophony, but case number restrictions provide clear evidence that this type of syncretism is not different from, e.g., case syncretism in its capacity to resolve feature conflicts and must therefore be reflected in the feature specifications of vocabulary items (see Zaenen and Karttunen 1984; Ingria 1990; Dalrymple and Kaplan 2000; Asarina 2011; also Pullum and Zwicky 1986 on ambiguity vs. neutrality).

I conclude that case number restrictions are predicted if Vocabulary Insertion of class exponents targets gender features directly, but not if gender and declension class are unrelated, or related by feature-filling redundancy rules. Semantic gender agreement in Russian therefore provides an argument for gender being present in the decomposition of class.

3.2 Decomposition of declension classes in Russian

This section provides a decomposition of declension classes in Russian. Since gender participates in the decomposition, I will start by laying out my assumptions concerning it.

I suggest that the three genders in Russian are formed by two binary features: [±fem] and [±masc]. Grammatically feminine nouns are [+fem][−masc], grammatically masculine nouns are [−fem][+masc], and neuter nouns are [−fem][−masc].

-

(30)

Out of the two gender features only [±fem] is targeted by declension class exponents. As shown in the introduction, gender alone is not enough to fully determine declension class, i.e., it must be accompanied by other features. I propose that declension classes arise from the combination of a gender feature and an idiosyncratic feature of a nominal stem [±α].Footnote 12 Note that declension classes are here understood as groups of nouns that take the same set of inflectional exponents. Four such groups of nouns—declensions—in Russian are identified by four possible combinations of two features: [±fem] and [±α]. Under this analysis, the features [±α] are analogous to the primitive class features ([ ], [

], [ ], etc.) in that their main function is to determine the declension class of a noun. The difference is that they do not determine classes by themselves but are targeted by Vocabulary Insertion together with gender. Decomposition of declension classes into gender and a formal feature allows us to capture the relation between gender and declension class in a way that was argued for in the previous section. It also allows us to group the declensions into natural classes, which will be necessary for the analysis of case number restrictions.

], etc.) in that their main function is to determine the declension class of a noun. The difference is that they do not determine classes by themselves but are targeted by Vocabulary Insertion together with gender. Decomposition of declension classes into gender and a formal feature allows us to capture the relation between gender and declension class in a way that was argued for in the previous section. It also allows us to group the declensions into natural classes, which will be necessary for the analysis of case number restrictions.

The table in (31) provides specifications for declension classes in Russian. Class  , made up of masculine nouns, and class

, made up of masculine nouns, and class  , made up of neuter nouns share the [−fem] feature. Classes

, made up of neuter nouns share the [−fem] feature. Classes  and

and  include feminine nouns, and both have [+fem]. Classes

include feminine nouns, and both have [+fem]. Classes  and

and  share [+α]. Classes

share [+α]. Classes  and

and  have [−α].

have [−α].

-

(31)

Exponents that appear only with nouns of one class (e.g., the class  instrumental exponent /ju/) have a full class specification, while exponents syncretic between declensions are underspecified for features that differentiate between these classes. For instance, the instrumental exponent /om/ is used with class

instrumental exponent /ju/) have a full class specification, while exponents syncretic between declensions are underspecified for features that differentiate between these classes. For instance, the instrumental exponent /om/ is used with class  as well as class

as well as class  nouns that differ in their values for [α]. This means that /om/ is underspecified for [±α]. Exponents syncretic between classes

nouns that differ in their values for [α]. This means that /om/ is underspecified for [±α]. Exponents syncretic between classes  and

and  are also underspecified for [±α]. Suffixes shared by nouns from classes

are also underspecified for [±α]. Suffixes shared by nouns from classes  and

and  or classes

or classes  and

and  are specified for [±α] but not for [±fem]. Note that although the features participating in decomposition are different, the natural classes produced this way match those suggested by Müller (2004) and Alexiadou and Müller (2008).Footnote 13

are specified for [±α] but not for [±fem]. Note that although the features participating in decomposition are different, the natural classes produced this way match those suggested by Müller (2004) and Alexiadou and Müller (2008).Footnote 13

Recall that profession-denoting nouns that allow for semantic gender agreement belong to class  . According to this decomposition of declension classes, class

. According to this decomposition of declension classes, class  nouns realize [−fem] by their inflection. This is line with the grammatical gender ([−fem][+masc]) of such nouns, but contradicts their semantic gender ([+fem][−masc]). As a result, nouns like vrač ‘doctor’ have conflicting values of the [fem] feature. This makes the derivation ineffable unless an exponent regularly used in a given form is underspecified for gender and consequently syncretic between classes

nouns realize [−fem] by their inflection. This is line with the grammatical gender ([−fem][+masc]) of such nouns, but contradicts their semantic gender ([+fem][−masc]). As a result, nouns like vrač ‘doctor’ have conflicting values of the [fem] feature. This makes the derivation ineffable unless an exponent regularly used in a given form is underspecified for gender and consequently syncretic between classes  and

and  .

.

Note also that class  , which is decomposed into [+fem] and [−α], includes a small group of nouns that denote male individuals and trigger masculine agreement in syntax. I suggest that this is an instance of deponency, a phenomenon known due the group of Latin verbs that show passive morphology but are active in syntax. Generally, deponency is defined as a mismatch between syntactic properties and morphological realization (see Embick 2000; Stump 2007; Müller 2013). Class

, which is decomposed into [+fem] and [−α], includes a small group of nouns that denote male individuals and trigger masculine agreement in syntax. I suggest that this is an instance of deponency, a phenomenon known due the group of Latin verbs that show passive morphology but are active in syntax. Generally, deponency is defined as a mismatch between syntactic properties and morphological realization (see Embick 2000; Stump 2007; Müller 2013). Class  masculine nouns are deponent because they are masculine ([+masc][−fem]) syntactically but realize a contradicting [+fem] feature morphologically. Thus, nouns have contradicting [−fem] and [+fem] features, exactly as profession-denoting class

masculine nouns are deponent because they are masculine ([+masc][−fem]) syntactically but realize a contradicting [+fem] feature morphologically. Thus, nouns have contradicting [−fem] and [+fem] features, exactly as profession-denoting class  nouns that give raise to semantic agreement. Masculine class

nouns that give raise to semantic agreement. Masculine class  nouns are however not subject to case number restrictions; realization of their inflection is not dependent on the transparadigmatic syncretism and underspecification of exponents. The difference between the two cases is due to the position of conflicting features in the structure and will follow from the analysis of morphological ineffability developed later in Sect. 4.

nouns are however not subject to case number restrictions; realization of their inflection is not dependent on the transparadigmatic syncretism and underspecification of exponents. The difference between the two cases is due to the position of conflicting features in the structure and will follow from the analysis of morphological ineffability developed later in Sect. 4.

3.3 Further evidence: Augmentative išč

The decomposition of the Russian declensions in (31) is further supported by the interaction between class and gender in nouns with the augmentative suffix išč.Footnote 14 If the affix is attached to a noun, the class of the derived noun is dependent on the original gender of the noun (see Švedova 1980: 213; Timberlake 2004: 146). In (32), the suffix appears on feminine (i.e., [+fem]) nouns that belong to different declension classes: (32a) shows a noun from class  , (32b) a noun from class

, (32b) a noun from class  . In both cases, the derived noun is feminine and bears class

. In both cases, the derived noun is feminine and bears class  inflection.

inflection.

-

(32)

In (33), išč attaches to non-feminine (i.e., [−fem]) nouns. The base in (33a) is originally masculine and belongs to class  ; the base in (33b) is neuter and belongs to class

; the base in (33b) is neuter and belongs to class  . In both cases the noun with suffix išč is neuter and inflects like a class

. In both cases the noun with suffix išč is neuter and inflects like a class  noun.

noun.

-

(33)

If išč is specified for [−α] but has no gender feature, the declension of a derived noun follows directly from the combination of this formal feature and the gender of the original noun: [−α] and [+fem] in (32) produce the feature specification of class  , [−α] and [−fem] in (33) that of class

, [−α] and [−fem] in (33) that of class  .Footnote 15

.Footnote 15

To sum up, in this section I have discussed which effect a change in the gender specifications of a noun can have on its inflection, and shown that the pattern predicted by approaches where inflection targets gender directly is the one that is empirically borne out under semantic gender agreement in Russian. Then, I presented a decomposition of the declension classes in Russian under which classes are built from two binary features: gender [±fem] and a purely formal feature [±α]. In the next section, I turn to the morphological realization of these features, and show how syncretism can resolve conflicts between them.

4 Ineffability in morphology

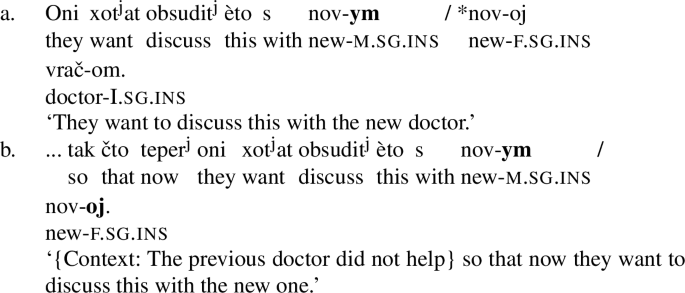

4.1 Subset principle

I adopt the framework of Distributed Morphology, according to which structures produced in syntax undergo morphological realization in a post-syntactic component (see Halle and Marantz 1993, 1994; Harley and Noyer 1999; Siddiqi 2010). In the course of this, Vocabulary Insertion matches bundles of features in terminal nodes to vocabulary items. Vocabulary Insertion applies according to the Subset Principle proposed by Halle (1997); see (34). This principle requires that the features of a vocabulary item match as many features present in a syntactic terminal as possible and that a vocabulary item introduces no new features. Thus, the vocabulary item’s features must either be identical to the features on the terminal or form a proper subset of them.

-

(34)

Vocabulary Insertion that is based on the Subset Principle cannot fail because of the presence of an additional feature. To illustrate this, consider the following case: node N1 bears the features [+α][−β]. Vocabulary Insertion finds an item I1 with the features [+α][−β], that is, the vocabulary item matches all features on the node. Node N2 differs from N1 in that it also has feature [ f ]. The type and the value of [ f ] play no role. It can be [−α], [+β], or a new feature [±γ]. If there is a vocabulary item I2 specified as [+α][−β][ f ], it will be inserted into N2 in accordance with the Subset Principle. If there is no such item, I1 will be chosen: the features of this vocabulary item are a subset of the features on N2, and the selected item is most specific for a given context. Thus, if there is a new feature on a node, and there is no more specific item that would match this new feature too, the less specific vocabulary item (I1 in this example) will be inserted. Independently of the identity of the new feature, Vocabulary Insertion succeeds.

At the same time, morphological ineffability that is due to the inability to provide an exponent for a node with conflicting features, and that gets resolved by a syncretic exponent is attested for various phenomena cross-linguistically; see, e.g., Groos and van Riemsdijk (1981) on matching in free relatives; Taraldsen (1981) on topicalization; Zaenen and Karttunen (1984), Dalrymple et al. (2009) and Asarina (2011) on right node raising; Schütze (2003), Bhatt and Walkow (2013), Bjorkman (2016) and Coon and Keine (2020) on predicative agreement with multiple targets; Citko (2005) and Hein and Murphy (2019) on ATB-movement. This poses a dilemma: on the one hand, data show that ungrammaticality in some forms stems from a failure during morphological realization. On the other hand, the model of morphology does not provide a reason for a crash.Footnote 16 Most of the approaches that model how conflicting features lead to ineffability share two ideas. First, conflicting features cannot co-exist within a single feature structure. They have to be stored in two separate structures that in turn can co-exist on one node, as shown in (35) for conflicting gender features.

-

(35)

Second, Vocabulary Insertion applies to each feature structure separately. A derivation converges only if the outputs happen to be phonologically identical and fails otherwise. Outputs are the same if the inserted vocabulary item is underspecified for conflicting features and is hence syncretic between at least two cells in a paradigm. Analyses differ in their hypotheses about the formal reason for the crash. For instance, Asarina (2011) postulates that distinct insertion rules cannot spell out material on a single node. Bjorkman (2016) suggests that two different vocabulary items on one node are morphologically uninterpretable. Coon and Keine (2020) propose that ineffability arises because morphology must pick one of the two selected items but it cannot do so. Essentially, all of these approaches impose a well-formedness constraint on the result of Vocabulary Insertion.

Cases of morphological ineffability with semantic gender agreement in Russian differ in that a noun does not have two full feature structures. It has two conflicting gender specifications but only one number feature and only one case feature. Encountering a similar issue, Asarina (2011) proposes that all features except for conflicting ones must be copied from one feature structure and inserted into another.

Such a duplication of features is not required under the approach developed by Hein and Murphy (2019). They propose an operation of intersection. It applies to two feature structures and produces one structure. If the original structures have features with conflicting values, the value for this feature will be absent in the unified feature structure: [+fem]∩[−fem] ⇒ [fem]. Vocabulary Insertion of an item that is specified for this feature then introduces a new feature and thereby violates the Subset Principle. The analysis was developed for ATB-movement in Polish and, given the vocabulary items provided for Polish interrogative pronouns by Hein and Murphy (2019), it correctly derives the data. However, the analysis runs into problems if there is a default maximally underspecified vocabulary item, because it can be always inserted without introducing new features.

In what follows, I will present an analysis of morphological ineffability. Ineffability arises in my approach, as in most others, because of an inviolable well-formedness constraint on morphological realization, but while other approaches introduce conceptually novel constraints, mine needs nothing beyond the independently necessary Subset Principle.

4.2 Interleaving lowering and vocabulary insertion

I suggest that a derivation is ineffable if the subset relation between features of a vocabulary item and a terminal that holds when Vocabulary Insertion applies is destroyed later in the derivation. This is possible if Vocabulary Insertion can be interleaved with Lowering. The analysis is based on two major assumptions.

First, the Subset Principle is refashioned from a procedural restriction on Vocabulary Insertion into a constraint that holds after a vocabulary item is inserted; see Arregi and Nevins (2012) for other examples of inviolable constraints in Distributed Morphology.

-

(36)

Second, Vocabulary Insertion is interleaved with Lowering. According to the standard DM view morphology consists of multiple modules, so that the whole structure or a sizable part of it (e.g., a phase as understood in Chomsky 2000, 2001) is subject to rules from one block (e.g, morphological structure rules), and only after operations from this block have applied to the top-most node operations from the next block (e.g., Vocabulary Insertion) can start applying. They process the structure anew, starting from the bottom (see Halle and Marantz 1993; Arregi and Nevins 2012). As a consequence, all Lowering operations apply before Vocabulary Insertion. Here, I at least partially depart from this modular architecture within morphology and suggest that morphology is a single module that processes a structure supplied by syntax from bottom to top. Morphological operations are still ordered so that, for instance, Impoverishment of a feature on a node applies before Vocabulary Insertion into this node, but Vocabulary Insertion into the bottom node does not have to wait till Impoverishment has applied to the top node; cf. Noyer (1992), Halle (1997) and González-Poot and McGinnis (2006) on interleaving Vocabulary Insertion and Fission; Chung (2009) on Vocabulary Insertion and Fusion; and also Dobler et al. (2011) and Piggott and Travis (2017) on Vocabulary Insertion and head movement. As a result, Lowering can counterfeed Vocabulary Insertion. Lowering is a head-to-head downward movement that alters structure lower in the tree (see Embick and Noyer 2001). Vocabulary Insertion, on the other hand, applies bottom-up (see Bobaljik 2000; Myler 2017). Under this approach, Lowering can target nodes to which Vocabulary Insertion has already applied. If Lowering is followed by Fusion that unifies two sister nodes into one (see Halle and Marantz 1993 and also Kramer 2016b for examples of Fusion applying after Lowering), this makes it possible to change features on a node after Vocabulary Insertion has already applied to it.

Consider the following derivation. In the first step in (37), node N2 undergoes Vocabulary Insertion, and vocabulary item I2 is inserted. The features of I2 fully match the features on the terminal. After this, morphological computation proceeds to node N1. It has to lower to N2, as shown in (38). After Lowering, N1 and N2 undergo Fusion. I assume that in the course of Fusion the feature set of one node is incorporated into the feature set of another node. If the original sets have the same feature, but with contradictory values, they cannot be both in the resulting feature set, but the more marked feature overwrites the less marked one; cf. the ban against conflicting features in well-formed feature sets in (Stump 2001: 41). For binary gender features, I assume that a feature with a positive value is more marked than a feature with a negative value, i.e., [+β] overwrites [−β]; cf. Noyer (1992); Nevins (2007), as well as Weisser (2018) on markedness with binary features. The resulting structure is provided in (39). Here, the Subset Principle is violated because the inserted vocabulary item is specified for [−β], which is not present on the node. Vocabulary Insertion applies to terminals only once, so that the inserted exponent cannot be altered at this stage; see Embick (2010: 23). The violation of the Subset Principle leads to a crash.

-

(37)

-

(38)

-

(39)

While here and in what follows I will talk about this process of more marked features replacing less marked ones as overwriting, it can in fact be formalized as a maximally general impoverishment rule [+α, −α] → [+α] that applies whenever the premise is met.

A similar derivation does not lead to ineffability if there is no vocabulary item fully matching the features of N2, and a vocabulary item I1 underspecified for [±β] is inserted; see (40). In this case, a change in the value of [β] does not result in a violation of the Subset Principle; see (42). The feature conflict is resolved by a syncretic underspecified exponent.

-

(40)

-

(41)

-

(42)

While this model allows Lowering to counterfeed Vocabulary Insertion, it is clearly not the case for all instances of Lowering. First, in some cases Lowering is not always followed by Fusion; see McFadden (2004) on Lowering in largely agglutinative Finno-Urgic languages. Second, the current application of Lowering is peculiar in that the targeted node is already specified for features introduced by Lowering and Fusion. I suggest that if the node is not yet specified for features that will be introduced by Lowering, the feature set on the node might be viewed as incomplete, and Vocabulary Insertion will be postponed until the feature set on the node is full. As a result, application of Vocabulary Insertion before Lowering is limited to configurations where lowering features are already present on a node, albeit with different values.

5 Case number restrictions derived

In this section, I will show how the analysis applies to the case number restrictions on semantic gender agreement in Russian. Recall that if a grammatically masculine noun trigger feminine agreement, morphology fails to realize inflection on the noun unless an exponent regularly used in a given form is underspecified for gender and thereby syncretic between classes  and

and  . Table (43) (repeated here from (15)) shows nominal inflection in Russian. Exponents that can be used under semantic gender agreement are boldfaced. Nominative plural exponents are italic because the analysis predicts they can resolve gender conflicts, but this cannot be tested empirically.

. Table (43) (repeated here from (15)) shows nominal inflection in Russian. Exponents that can be used under semantic gender agreement are boldfaced. Nominative plural exponents are italic because the analysis predicts they can resolve gender conflicts, but this cannot be tested empirically.

-

(43)

5.1 Nominal inflection in Russian

Nominal inflection in Russian cumulatively realizes case, number, class (i.e., gender and [±α]), and sometimes animacy. These features are often assumed to originate in different projections. For instance, grammatical gender is on n (see Kramer 2015, 2016a), number is on Num (see Ritter 1991), and case originates outside the noun phrase. In Russian, all these features are realized by a single exponent, and assuming that Vocabulary Insertion targets terminals (see Halle and Marantz 1993; Halle 1997), this means that they have to be gathered on one node. Nouns in Russian stay low: they follow modifiers such as numerals, adjectives, and demonstratives in the regular case. Thus, features realized by nominal inflection must also be low in the noun phrase structure. I suggest that they are on the n head,Footnote 17 which is inherently valued with some nominal features (e.g, gender) and has unvalued probes for others (e.g., number and case).Footnote 18

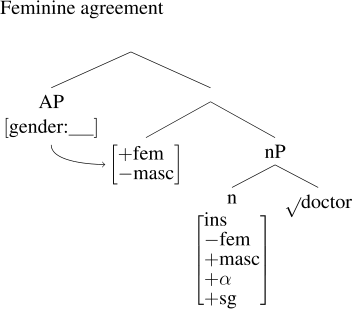

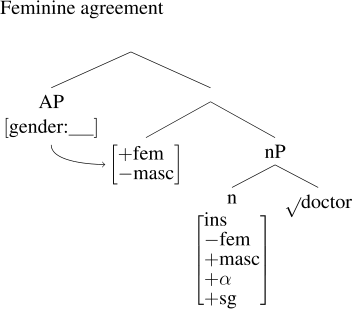

In addition to their grammatical gender, nouns can optionally have a semantic gender. Semantic gender in Russian is widely argued to be introduced by a higher functional projection in the nominal structure (see Sauerland 2004; Pereltsvaig 2006; Asarina 2009; Steriopolo and Wiltschko 2010; Pesetsky 2013; King 2015; Lyutikova 2015; Steriopolo 2019). Evidence for the higher position of semantic gender in Russian comes from the height restrictions illustrated in Sect. 2.1. They show, first, that low classifying modifiers cannot agree in semantic gender and, second, that agreement in the grammatical masculine gender can switch to the semantic feminine gender but not the other way around. I further assume that the position of a projection with semantic gender is not fixed as there is no consistent height, at which grammatical agreement obligatory switches to semantic agreement. Semantic gender differs from other features introduced higher in the nominal structure in that at the point when it is introduced, the n head is already specified for (grammatical) gender. As a result, unlike other nominal features that originate in higher projections, semantic gender does not appear on the n head via Agree but lowers to n in the morphological component.

Structure (44) shows the relevant part of a noun phrase as it is built by syntax. Here and throughout, I do not include animacy because all discussed nouns are animate. I also abstract away from the decomposition of case; see Müller (2004); Wiese (2004); or Caha (2019) for some options.

-

(44)

In (44), the n head is specified for the grammatical gender [−fem][+masc] and the formal feature [±α]. These features are often idiosyncratically associated with nominal roots, but roots are acategorial and featureless (see Marantz 1997; Acquaviva 2009) so that n cannot acquire these features via Agree with them. Generally, how to ensure a correct pairing between roots and their idiosyncratic features without endowing roots with features is a long-standing question in Distributed Morphology. The relation between roots and such features is usually conceived of as licensing, but unless analyzed as Agree, licensing remains a vague, undefined concept. I suggest that the correct distribution of features on n is derived by two mechanisms. First, since syntax does not refer to [±α], this feature can be introduced in morphology by a rule as in (45) that inserts positively valued feature in the presence of some roots and the negatively valued feature in the presence of others; cf. Embick (2010) and Kramer (2015) for post-syntactic insertion of a class feature.Footnote 19

-

(45)

Second, gender features that are required in syntax for agreement cannot be inserted postsyntactically. I suggest that the connection between nouns and genders follows from selection in syntax. Depending on the gender features, n heads have different selectional restrictions. For instance, the n head with [−fem][+masc] selects for \(\sqrt{}\)doctor, among other roots. This approach requires differentiating roots in syntax, a position argued for by Harley (2014) for independent reasons.

5.2 Conflicting gender features in Russian noun phrase

Everything is now in place to derive the case number restrictions on semantic gender agreement in Russian. Let us consider the instrumental singular form. Morphology processes the structure bottom-up and starts by supplying the vocabulary item /vrač/ for the root \(\sqrt{}\)doctor. After this, the derivation proceeds to the next higher node—n. It bears case [ins], number [+sg], grammatical gender [−fem][+masc] and [+α]. Russian has three instrumental singular exponents, listed in (46). The vocabulary item in (46a) is syncretic between classes  and

and  , so it has the [−fem] feature but is underspecified for [±α]. The vocabulary item in (46b) realizes inflection on class

, so it has the [−fem] feature but is underspecified for [±α]. The vocabulary item in (46b) realizes inflection on class  nouns and has a full feature specification: [+fem][−α]. Similarly, the vocabulary item in (46c) is used only with class

nouns and has a full feature specification: [+fem][−α]. Similarly, the vocabulary item in (46c) is used only with class  nouns and realizes [+fem][+α]. Out of these vocabulary items, only the one in (46a) can be inserted without a violation of the Subset Principle. The other exponents are specified for [+fem], which the n head does not have at this stage. Vocabulary Insertion is illustrated in (47).

nouns and realizes [+fem][+α]. Out of these vocabulary items, only the one in (46a) can be inserted without a violation of the Subset Principle. The other exponents are specified for [+fem], which the n head does not have at this stage. Vocabulary Insertion is illustrated in (47).

-

(46)

-

(47)

If the noun does not have semantic gender features, nominal inflection is essentially finished at this point. However, if a noun triggers semantic feminine agreement, there are feminine features higher in the structure. Belonging to features of the noun, semantic gender has to lower to the n head and be incorporated into its feature structure; see (48). When two nodes fuse, the new more marked feature [+fem] overwrites the less marked [−fem] feature on n as well as the less marked [−masc] that lowers as part of the semantic gender gets overwritten by a more marked [+masc] already present in the n head.Footnote 20 The resulting structure is given in (49). After Lowering and Fusion, features on n are changed so that features of the inserted vocabulary item are not in the subset relation to them anymore: the vocabulary item is specified for [−fem], which is now absent from the node. The violation of the Subset Principle and inability to exchange the already inserted exponent leads to the realization failure.

-

(48)

-

(49)

Thus, the morphological component fails to realize the instrumental singular inflection on the grammatically masculine class  noun in the presence of the semantic feminine gender. Given that this feminine feature enables feminine agreement in syntax, this derives the restrictions on semantic feminine agreement with masculine profession-denoting nouns in the instrumental singular as well as in other forms where inflection is specified for gender.

noun in the presence of the semantic feminine gender. Given that this feminine feature enables feminine agreement in syntax, this derives the restrictions on semantic feminine agreement with masculine profession-denoting nouns in the instrumental singular as well as in other forms where inflection is specified for gender.

A derivation with a semantic gender feature that does not result in ineffability is illustrated in (51)–(53) on the basis of the accusative plural. In this form, the noun vrač takes the exponent /ej/ that is syncretic between classes  and

and  . Another vocabulary exponent used in accusative plural contexts is /ø/, which is syncretic between classes

. Another vocabulary exponent used in accusative plural contexts is /ø/, which is syncretic between classes  and

and  . Both affixes are specified for [±α] and underspecified for [±fem]; see (50). As shown in (51), the vocabulary item /ej/ with the feature [+α] is chosen to realize inflection on the masculine class

. Both affixes are specified for [±α] and underspecified for [±fem]; see (50). As shown in (51), the vocabulary item /ej/ with the feature [+α] is chosen to realize inflection on the masculine class  noun.

noun.

-

(50)

-

(51)