Abstract

Cases of apparent V3 order in German finite main clauses are commonly attributed to remnant VP movement to SpecC. The remnant VPs posited in this approach are headed by a trace, left behind by a verb that evacuated from VP prior to the movement of VP. Müller (2018) argued that such remnant VPs are subject to a process of restructuring that removes the verb’s trace and reassociates the phrases that depended on that head prior to its removal. This commentary discusses novel observations about operator scope which lend further support to the remnant movement approach to apparent V3, but which at the same time are inconsistent with the assumption that remnant VPs in the German prefield are always subject to restructuring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

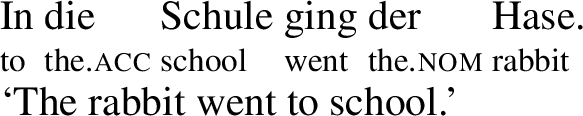

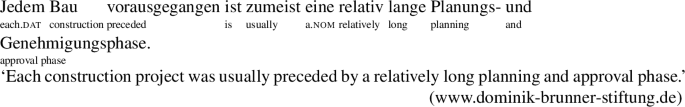

German is said to be a V2 language, meaning that the “prefield,” the region that in a canonical declarative main clause precedes the finite V in the “left bracket,” typically consists of a single surface constituent. The V2 property of German is illustrated by example (1), given that the sequence in its prefield, in die Schule (‘to school’), constitutes a single PP.

-

(1)

In a commonly assumed baseline analysis of V2, the left bracket is identified with C and the prefield with the specifier of C (SpecC). Both C and SpecC are typically filled by movement from within the sister of C. This is the case in (1), which under the baseline analysis has the structure sketched in (2).

-

(2)

[\(_{\text{CP}}\) [\(_{\text{PP}}\) in die Schule]1 [\(_{\text{C'}}\) [\(_{\text{C}}\) ging2 ] [der Hase t\(_{\text{1}}\) t\(_{\text{2}}\) ] ] ]

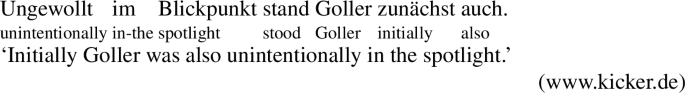

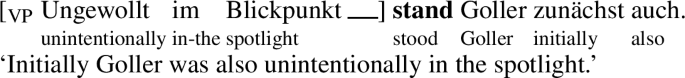

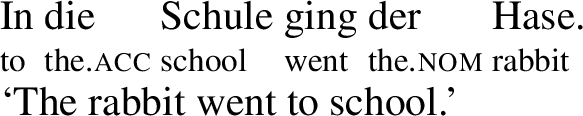

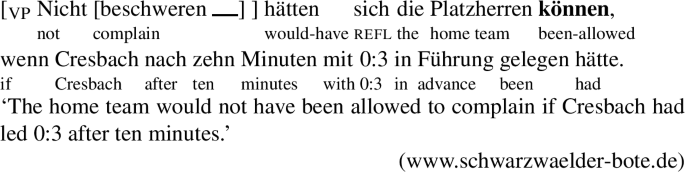

Assuming that C permits only one specifier position, and assuming that this position must be filled by a constituent, this analysis leaves no room for possible V3 clauses, clauses where the prefield hosts multiple constituents that cannot be parsed as jointly constituting a single larger unit. The baseline analysis is therefore challenged by examples that do, at first sight, seem to instantiate such a V3 profile. Example (3) is a case in point, given that there is no credible parse where ungewollt, an AdvP, merges with im Blickpunkt, a PP, into a single constituent.

-

(3)

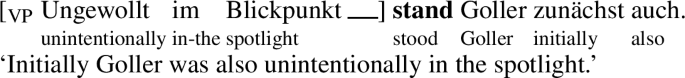

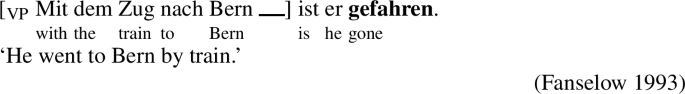

The predominant approach to such data reconciles the appearance of V3 with the baseline analysis by positing a silent V head within the prefield (e.g., Fanselow 1993; Müller St. 2005, 2015; Müller 2018). This allows for a parse of apparent V3 where the overt phrases in the prefield integrate into a VP, as complements or modifiers, and where that VP constitutes the single constituent in SpecC. As for why the head of that VP may be silent, one option is that it is a trace left by V movement out of VP prior to VP fronting to SpecC. In particular, V might escape VP by way of head movement to C. On this view, apparent V3 arises from a type of remnant movement, movement of a VP that lost some of its overt content through extraction prior to VP fronting. While initially posited to account for fronted VPs that seem to be missing phrasal elements (e.g., den Besten and Webelhuth 1990; Müller 1998; Thiersch 2017), cases of apparent V3 can be taken to indicate that remnant movement may also be fed by head movement (e.g., Fanselow 1993; Müller St. 2005, 2015; Müller 2018). On the remnant movement analysis, the structure of the apparent V3 sentence (3) has the format sketched in (4), with V instantiated by stand, XP by ungewollt (AdvP), and YP by im Blickpunkt (PP).

-

(4)

Müller (2018) reviews a range of compelling arguments for a remnant movement analysis of apparent V3. However, developing this approach further, Müller also presents very interesting arguments that structures like (4) only exist as temporary stages in syntactic derivations of surface forms, not as derivations’ final outputs. Müller argues that a derivation that yields (4) carries on by mapping this structure to (5) as the final surface form output.

-

(5)

For the intended mapping from (4) to (5), Müller posits processes of removal and reassociation of nodes in temporary structures. In the case at hand, node removal deletes the silent V head within the fronted VP in (4). As a consequence, all higher nodes in the verbal spine must be removed as well. This leaves the dependent phrases XP and YP orphaned, having lost their initial attachment sites. Reassociation of these phrases results in their integration into the projection of C, yielding the final output structure sketched in (5).

Müller suggests that in final output structures, V traces must not be unbound. That is, V traces must be c-commanded by their antecedent verbs in the final outputs of syntactic derivations. This means that a syntactic derivation can never terminate with a structure like (4) as the final output. Hence derivations that reach a structure like (4) not only can continue, but must continue to (5) by way of node removal and reassociation.

The goals of the commentary below are twofold. First, I will offer a novel type of evidence for the existence of structures like (4), hence for a remnant movement analysis of V3. The evidence invokes ambiguities introduced by operators—I will focus on negation—that can attach at different heights in nested VP structures. The evidence is of a new type in that it rests on intuitions about meaning, viz. operator scope, rather than intuitions about acceptability per se. Second, I will point out that the new scope data presented are inconsistent with the assumption that node removal and reassociation can always apply to structures like (4), hence the assumption that syntactic derivations can always map such structures to outputs like (5). This finding is in obvious conflict with the arguments in support of this mapping presented in Müller (2018). I will not attempt here to resolve this conflict, or even discuss it in depth. Instead, my hope is merely to convince the reader of its existence, and to set the stage for a resolution in future work.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 introduces the central scope data. Section 3 proposes that such data can be understood in terms of remnant VP movement to the prefield. Section 4 points out that scope relations in the relevant type of data are inconsistent with the fronted remnant VP being subject to the processes of structure removal and reassociation. In concluding, Sect. 5 identifies a natural starting point for future work by singling out the argument in Müller (2018) that most directly conflicts with the present findings.

2 A scope puzzle

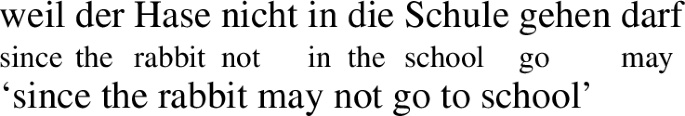

Given that in German, verbal projections are head final, it is predicted that the position of a modifier at the left edge of a nested VP can be consistent with multiple attachment sites. Consider the case of modification by negation. It is expected that a negation that precedes a nested VP can be parsed as attaching to the higher VP, as sketched in (6a), or as attaching to the lower VP, as sketched in (6b).

-

(6)

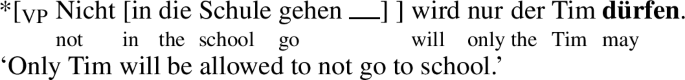

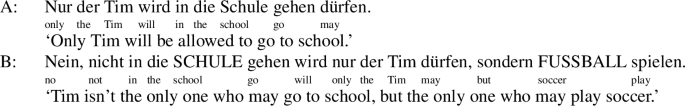

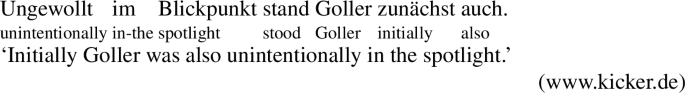

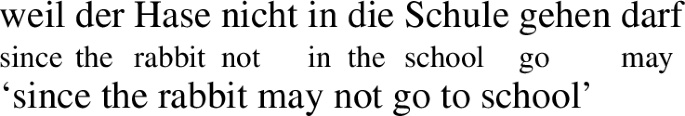

Persuasive evidence that German indeed permits such variable attachment height for negation comes from observations about meaning, viz. in cases where the higher verb scopally interacts with negation. Modal verbs serve to illustrate this point. Consider (7), for example, where the lower VP is in die Schule gehen (‘go to school’) and the higher VP is headed by the possibility modal dürfen (‘may,’ ‘be allowed’).

-

(7)

Assuming a transparent mapping from syntax to semantics, high attachment of negation, as in (6a), is predicted to yield the “high NEG” reading paraphrased in (8a), whereas low attachment of negation is predicted to result in the “low NEG” reading in (8b).

-

(8)

-

a.

“High NEG” (available)

The rabbit is not allowed to go to school.

-

b.

“Low NEG” (available)

The rabbit is allowed not to go to school.

-

a.

It is well known that this predicted type of ambiguity is indeed attested. Supporting the availability of both structure (6a) and structure (6b), sentence (7) can be understood either as reporting a prohibition, as in the high NEG reading (8a), or as reporting a permission, as in the low NEG reading (8b).

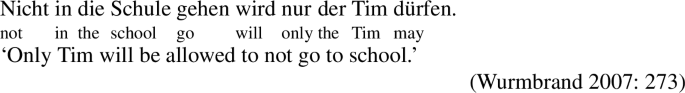

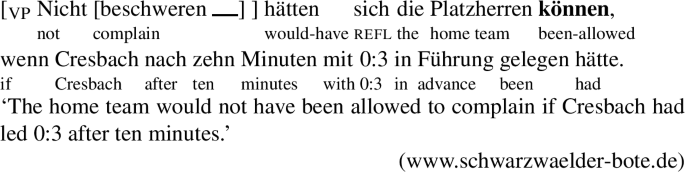

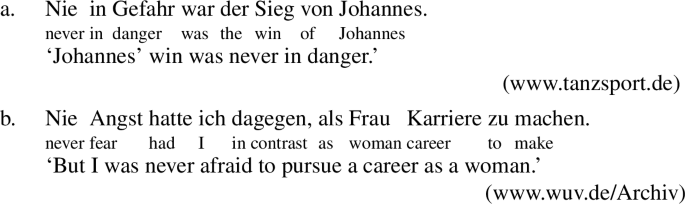

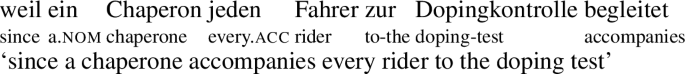

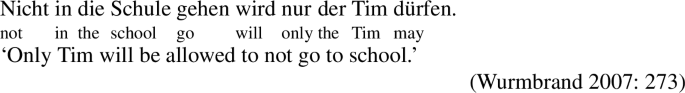

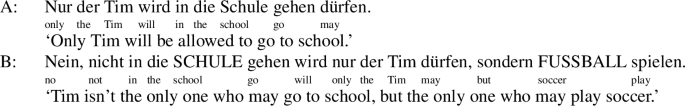

Against this background, Wurmbrand (2007) examines nested VPs with negation in German V2 clauses.Footnote 1 Wurmbrand considers V2 clauses where the prefield hosts a sequence that consists of negation and the lower VP segment of a nested VP. Wurmbrand’s example in (9) is a case in point.

-

(9)

Wurmbrand reports that (9) can be understood in the low NEG reading (10b), reporting a permission, but not in the high NEG reading (10a), which would report a prohibition.Footnote 2

-

(10)

-

a.

“High NEG” (unavailable)

Only Tim is not allowed to go to school.

-

b.

“Low NEG” (available)

Only Tim is allowed not to go to school.

-

a.

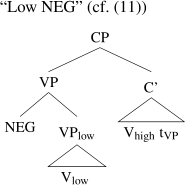

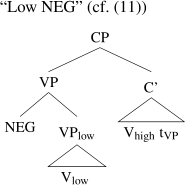

Wurmbrand proposes to understand this observation as showing that the V2 order in (9) excludes the pre-movement structure of the VP in (6a) and forces the pre-movement structure in (6b), deriving the parse for (9) sketched in (11) as the only well-formed option. Assuming the derivation of V2 order with VP fronting does not expand the scope options that the structure encodes prior to movement, Wurmbrand’s observation about (9) is then captured.Footnote 3

-

(11)

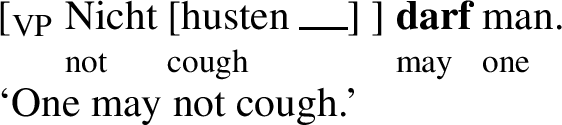

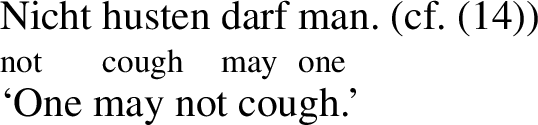

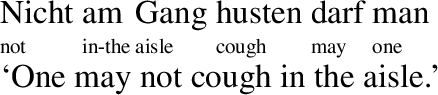

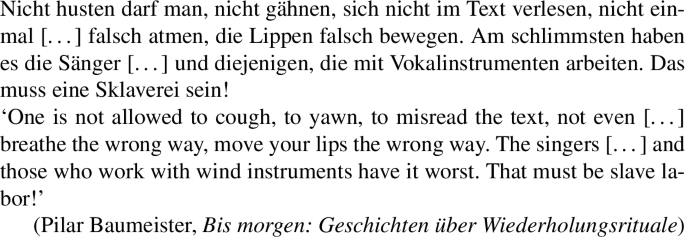

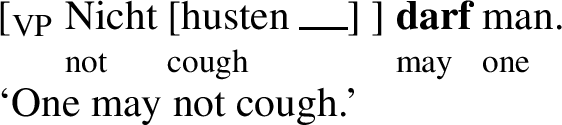

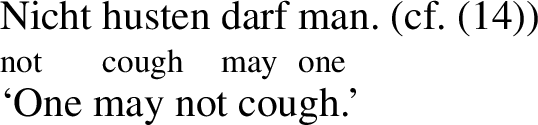

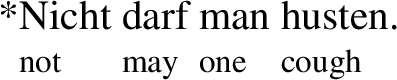

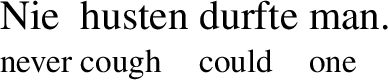

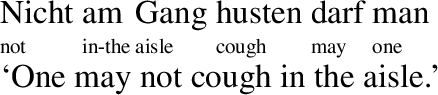

So all may seem as it should be. However, a puzzle emerges from a broader survey of relevant data. To begin, consider the clause in (12), which is similar in shape to (7), with negation at the left edge of a nested VP, featuring the low VP husten and a high VP headed by a modal, again the possibility modal dürfen.

-

(12)

As expected, this clause gives rise to the same sort of high-low NEG ambiguity as (7). It permits the (pragmatically more plausible) high NEG reading (13a), reporting a prohibition, as well as the (somewhat less plausible) low NEG reading (13b), reporting a permission.

-

(13)

-

a.

“High NEG”

One is not allowed to cough.

-

b.

“Low NEG”

One is allowed not to cough.

-

a.

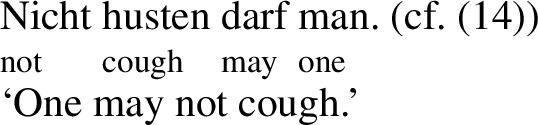

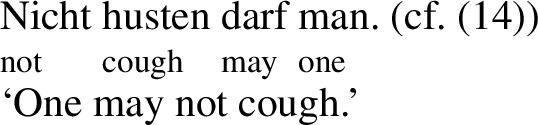

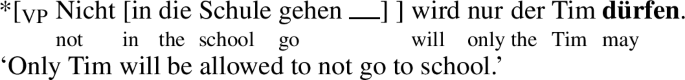

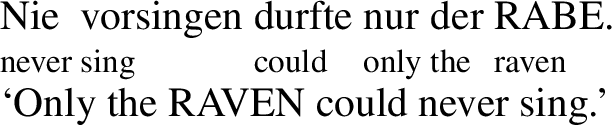

Example (14) is a main clause version of (12), and parallel in form to Wurmbrand’s example (9). Just like (9), (14) features a finite verb, here the modal darf, that is preceded by a sequence consisting of negation and the low VP.

-

(14)

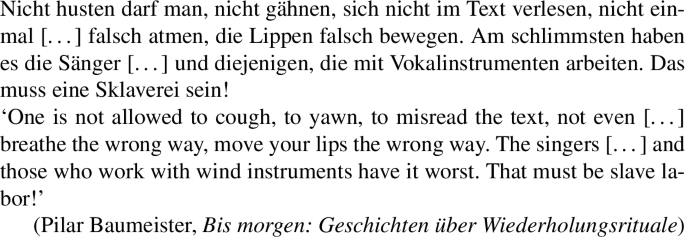

Given Wurmbrand’s analysis of (9), there is no reason to expect that (14) would differ from (9) with regard to intuitions about the where negation can take scope. There is no reason to expect that (14) might permit a high NEG reading any more than (9) does. And yet, it appears that (14) does permit such a reading. The sentence can certainly be read as reporting (13b), that one is allowed not to cough, but it can also be understood as conveying (13a), that one is not allowed to cough. Supporting this assessment, a high NEG reading of (14) is clearly intended in the naturally occurring use in the context of (15), a text concerned with activities that musicians or singers are not allowed to engage in.Footnote 4

-

(15)

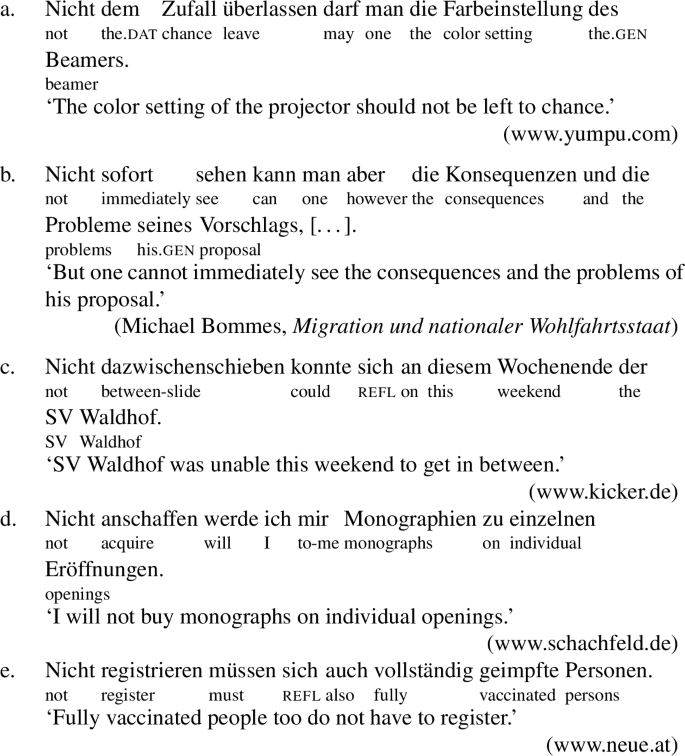

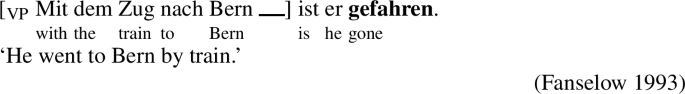

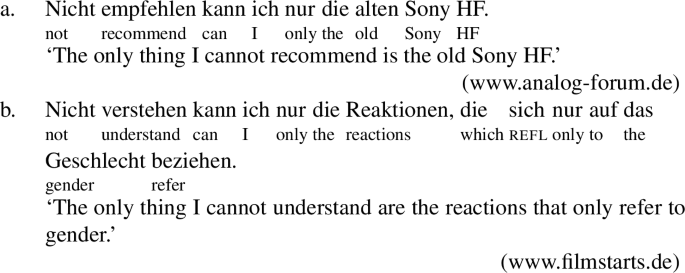

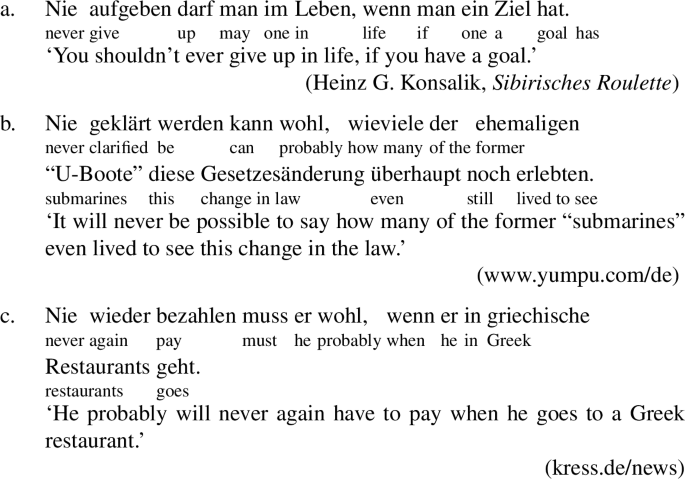

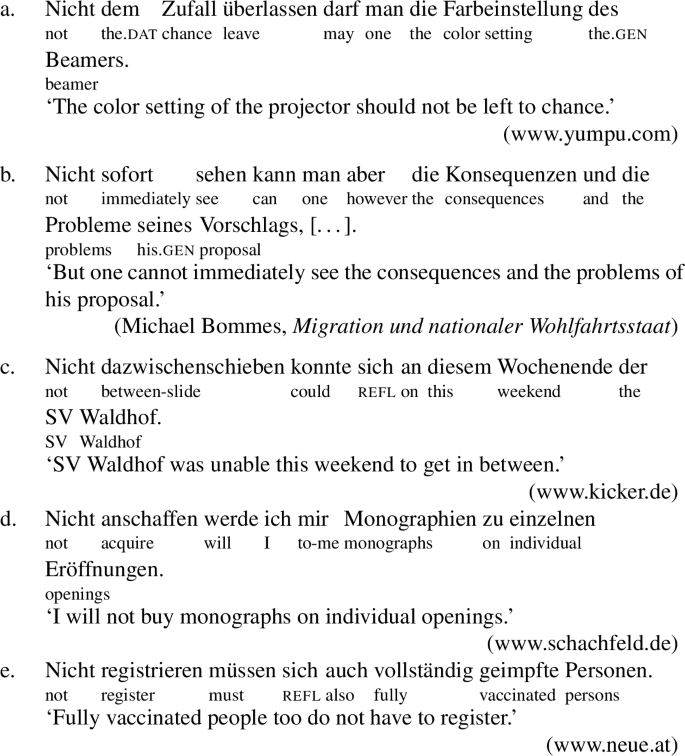

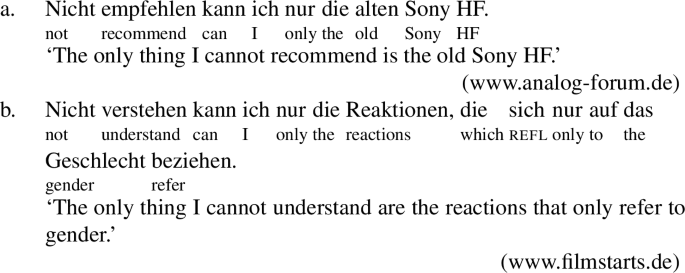

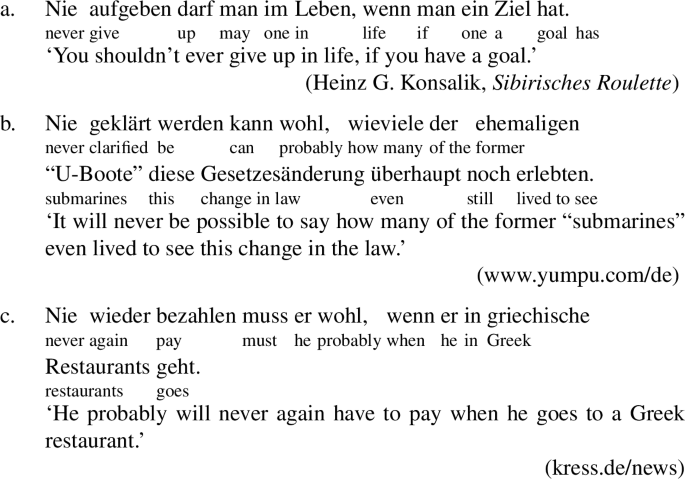

Apparently, then, high NEG readings are not in general inaccessible in finite main clauses whose prefield features a low VP preceded by negation. So it cannot be this syntactic profile per se that excludes the high NEG reading for Wurmbrand’s example (9). In the following, I will refer to the unexpected extension of negation’s scope over a modal verb in cases like (14) as NEG extension. To further confirm the existence of the NEG extension effect, (16) presents a selection of naturally occurring examples of much the same profile as (14).

-

(16)

While in each of the sentences in (16), the prefield features an initial negation together with the head of a low VP, in all of these cases a DP complement of that verbal head is stranded in the sentence’s “middle field,” following the finite verb in the left bracket. For present purposes, these examples nevertheless form a natural class with (14). In each case, the form of the prefield seems to exclude a pre-movement parse like (6a). In fact, it is reasonable to maintain that negation is followed by a full low VP constituent in all of the prefields in (14) and (16), viz. a remnant VP (e.g., den Besten and Webelhuth 1990; Müller 1998; Thiersch 2017). That is, it can reasonably be assumed that the complement DP left VP via scrambling prior to VP being fronted to the specifier of C. If only for ease of exposition, I will in the following keep talking as though all of the relevant examples have a prefield comprised by a negation and a complete VP projection.

The examples in (16) are in any case puzzling for the same reason as sentence (14). Despite a surface form that seems to preclude a pre-movement structure like (6a), each of these examples illustrates NEG extension, as a high NEG reading is available. In each case, given the sentence’s content and context, it is in fact clear enough that a high NEG reading is intended by the author: (16a) states that is not acceptable to leave the color setting to chance; (16b) refers to a proposal with consequences that are not possible to see immediately; (16c) talks about a soccer club that was not able to advance in the standings; (16d) is about a type of book the writer proclaims to not buy at any future time; and (16e) identifies people who are not required to register.

How is NEG extension to be accounted for? How does negation manage to outscope a modal in cases where the prefield consists of negation and a low VP that excludes the modal, as in the examples in (14) and (16)? Why does the surface form of the prefield in such cases not force a low NEG reading, as it would according to Wurmbrand’s rationale in her interpretation of (9)? The remainder of this paper will propose an answer to this question, and detail the consequences of this answer for the analysis of apparent V3.

3 Scope over silent heads

The remnant movement approach to apparent V3 reviewed in Sect. 1 sets the table for a straightforward analysis of NEG extension. It is natural to postulate that sentences like (14), repeated here as (17), permit structures like the one sketched in (19) in addition to structures like (11), also repeated here as (18).

-

(17)

-

(18)

-

(19)

The high NEG structure in (19) is transparently parallel to (4) above, the structure posited as a source for apparent V3 in examples like (3). In (19), the silent V head in the prefield is the trace of the high modal. Since the high VP is projected in SpecC, negation can attach to this high VP. Therefore, despite initial appearance, and contrary to what Wurmbrand (2007) assumed, the word order in examples like (14)/(17) is compatible with the base VP structure (6a), not just the one in (6b). Assuming that the modal verb in (19) is interpreted in the position that it occupies in this base position, that is, in the position of its trace, NEG extension is captured.

As for the low NEG reading, it can be assumed to arise as before. If we continue to assume that both of the attachments sites for negation shown in (6) are possible, (11)/(18) will be available in addition to (19), capturing the low NEG reading.

An obvious question left open by this proposal, however, is why NEG extension is not available in Wurmbrand’s (2007) example (9). This example is shown again in (20).

-

(20)

Some annotation is added here for transparency, so as to sketch the parse under consideration. Square brackets are used to mark the remnant VP parsed as occupying SpecC, a line marks the position of the empty V inside the fronted VP posited for a high NEG structure, and boldface marks the overt verb external to SpecC that is taken to have originated in that position. The asterisk in (20) reflects Wurmbrand’s observation that the sentence is not actually intuited to permit the high NEG reading that this structure would derive.

Now, why would Wurmbrand’s example resist such a parse, while at the same time the corresponding high NEG structure for (14), indicated now in (21), is available?

-

(21)

Based on the limited range of data considered above, it would be natural to speculate that the correct answer must reference the position of the modal verb, the overt verb that is interpreted in the empty V position within the remnant VP. In (21), the modal is the finite verb in the left bracket, whereas in (20), the modal is a non-finite verb that appears at the end, in the sentence’s “right bracket.” On an intially plausible hypothesis, C is the only position for a verb to target when extracting from VP. Predicting that only finite verbs in C can be external to VP (and assuming as before that finite verbs in C can be interpreted in their base position), this hypothesis captures the contrast between (20) and (21).

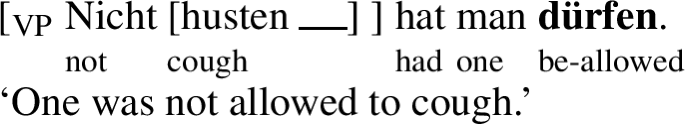

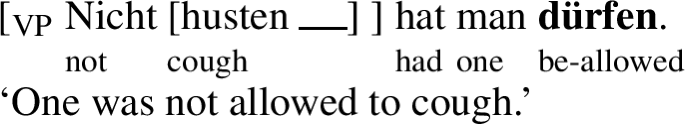

However, a more comprehensive survey of relevant data reveals that the hypothesis just stated is too strong. NEG extension is not limited to cases where the modal is a finite verb in the left bracket. In the constructed variant of (21) shown in (22), the modal is again a non-finite occupant of the right bracket, and yet the sentence seems to permit a high NEG reading, hence seems to permit the parse indicated in (22). The naturally occurring example in (23), which is parallel in structure to (22) and is clearly intended in a high NEG meaning, further confirms that NEG extension does not require a modal appearing in C.

-

(22)

-

(23)

So we are still left with the question what it might be about Wurmbrand’s example (20) that renders NEG extension inaccessible there. Moreover, under the remnant movement analysis of NEG extension, a further issue now arises, viz. what position non-finite verbs in cases like (22) and (23) might target when extracting from VP prior to VP fronting to SpecC.

I do not have conclusive answers to these question to offer here. Crucially, however, much the same questions arise independently under the remnant movement analysis of apparent V3. Alongside apparent V3 cases like (3), repeated below in (24), where the verb that left a trace in the remnant VP is finite and appears in C, we find examples like (25), where the corresponding verb is non-finite and sits in the right bracket. And one finds sequences like (26), which looks no different from acceptable cases of apparent V3 in terms of constituent structure, and yet does not even come close to being acceptable itself.

-

(24)

-

(25)

-

(26)

Müller (2018: fn. 25) suggests that apparent V3 cases like (25) can be interpreted as showing that non-finite verbs can optionally extract from VP by moving rightward to the head of a higher vP. (See Müller St. 2005, 2015 for a proposal with similar effects in a different framework.) This plausible suggestion could be adopted to capture high NEG readings in examples like (22) and (23). As for the restrictions on apparent V3 illustrated by (26), the leading hypothesis in the literature on apparent V3 order, also endorsed in Müller (2018), is that the acceptability of the relevant remnant movement parses is subject to conditions that reference information structure (Bildhauer and Cook 2010; Müller 2015). Regardless of the precise nature of these conditions, the same could plausibly be true for NEG extension as well. For all we have seen, then, restrictions on scope of the sort illustrated by Wurmbrand’s example (20) are not surprising, and do not challenge the remnant movement analysis of NEG extension. At least, they do not challenge this approach any more than the unacceptability of examples like (26) challenges the remnant movement analysis of apparent V3.Footnote 5

4 Silent heads resisting removal

Positing remnant movement of a VP headed by a trace, the analysis of NEG extension proposed above is fully aligned with the remnant movement approach to apparent V3. A question that remains, however, is how the negation scope data mesh with the further development of this approach in Müller (2018), outlined in Sect. 1. Consider again the remnant movement structure in (19) for a sentence like (14), both repeated below.

-

(27)

-

(28)

To recap, Müller (2018) suggests that a fronted VP headed by a trace can only be licit as an intermediate stage of a syntactic derivation. The idea is that such a configuration is illicit as a derivation’s final output because fronting of the remnant VP breaks the c-command between the trace and the verb that left it behind, leaving the trace unbound. Müller proposes that in order to arrive at a licit final output structure in such cases, the offending trace must be eliminated by node removal, followed by reassociation of the elements who in the process lost their attachment site in the spine of the projection headed by the deleted verb. Those elements are taken to reassociate by attaching to nodes in the C projection instead. In the case of (19)/(28), the relevant dependent elements are NEG and the lower VP segment. By Müller’s assumptions, therefore, node removal and reassociation can and must apply to a structure like (19)/(28), mapping it to (29) below as the derivation’s final output.

-

(29)

Does this elaboration of the remnant movement analysis make adequate predictions for NEG extension data? The remainder of this section argues that it does not. Section 4.1 shows that NEG extension data are incompatible with the assumption that restructuring must always apply to structures like (19)/(28). Section 4.2 makes the stronger point that NEG extension data are even incompatible with the assumption that restructuring can always optionally apply to structures like (19)/(28).

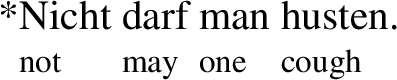

4.1 Obligatory restructuring and undergeneration

The shape of the reconfigured prefield in (29) immediately raises a question. It is known that negation nicht is not possible as the sole occupant of the German prefield in V2 clauses (e.g., Jacobs 1982: Sect. 3.2.3; Jäger 2008: Sect. 2.3; Zeijlstra 2013). Sentence (30), for example, is judged as sharply unacceptable. The natural interpretation of this judgment is that the structure in (31) is ill-formed as the final output of a syntactic derivation, on the grounds of negation appearing in SpecC. But since (29) is an instance of (31), this conclusion is evidently inconsistent with the assumption that (29) is well-formed.

-

(30)

-

(31)

This means that the proposed remnant movement analysis of NEG extension is incompatible with Müller’s assumption that unbound traces must always be removed. This assumption leaves no room for a syntactic derivation outputting a structure that would capture a high NEG reading for (14). By hypothesis, NEG extension requires remnant movement of the negated higher VP. But under Müller’s assumptions, there is no well-formed parse of this sort. An output structure without removal and reassociation, as in (19), is excluded in virtue of containing and illicit unbound trace, while an output structure where these processes have applied, as in (29), violates whatever condition regulates the distributional requirements of nicht.Footnote 6

Therefore, under the assumption that structures like (31) are invariably ill-formed, Müller’s proposal undergenerates. To capture NEG extension, we must reject the strong hypothesis that unbound traces must always be eliminated in a derivation’s final output structure. To allow for remnant movement parses like (19) to be well-formed and to capture NEG extension in data like (14), it must be that under the right conditions, at least, a verb’s unbound trace in the prefield must be tolerated, hence that node removal and reassociation are not obligatory.

Is there a way to escape this conclusion? Trying to preserve Müller’s proposal unaltered, one could perhaps reject the assumption that structures of the form in (31) are invariably ill-formed. One could speculate, for example, that the correct explanation of the unacceptability of examples like (30) must reference the structural or linear adjacency of negation and the finite verb. In that case, the structure in (29) could perhaps pass as well-formed, given that there another phrase, the low VP, separates negation from the finite verb in C. Since in this structure, NEG c-command the rest of the sentence, it is only natural to assume that it enables wide scope for nicht. In fact, Müller explicitly assumes that an operator may take semantic scope over the c-command domain it acquires via node removal and reassociation. If so, the high NEG reading for (14) would be accounted for.

However, the assumption that the structure in (29) is well-formed does not actually restore descriptive adequacy. While preventing undergeneration for (14), it runs into problems of overgeneration in closely related cases. As just noted, given that negation c-commands the remainder of its clause in (29), it is now predicted that NEG extension amounts to negation taking global scope in its clause. This prediction is certainly unproblematic for the particular example in (14). Since in that case, the modal is the only scope-bearing element below negation, taking global scope simply amounts to taking scope over the modal. However, we will now see that the prediction from (29) is not correct in general.

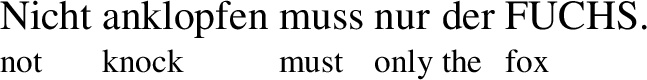

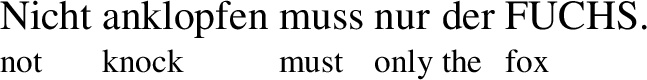

Consider the example in (32). This sentence is structurally parallel to NEG extension examples like (14), but it features an additional operator within the middle field, viz. the focus sensitive exclusive particle nur (‘only’). Here and below, capitalization identifies the focused constituent that nur is intended to associate with, and signals a falling pitch accent within the capitalized word (e.g., Jacobs 1983).

-

(32)

What are the intuitions about the meaning of (32)? Once again, a high-low NEG ambiguity can be detected. The sentence certainly permits the low NEG reading paraphrased in (33b), where nur takes global scope, outscoping both negation and the modal. In that reading, (32) implies that the fox is required not to knock, hence not allowed to do so. But in an alternate understanding that seems available, (32) conveys the high NEG reading in (33a). This reading, where nur once again scopes globally, implies that the fox is not required to knock, hence is allowed not to do so.

-

(33)

-

a.

“Non-global high NEG” (available)

Only the FOX is not required to knock.

-

b.

“Low NEG” (available)

Only the FOX is required not to knock.

-

a.

So (32) permits NEG extension within the scope of the exclusive particle. That NEG extension can indeed go along with global scope of an exclusive particle surfacing in the middle field is confirmed by the naturally occurring examples in (34).

-

(34)

It seems uncontroversial that, as reflected by the proposed English translations, these sentences can be understood with global scope for the exclusive particle. Moreover, it seems possible for this global scope to coexist with NEG extension, that is, with negation being understood as scoping above the modal. In fact, this is how (34a) and (34b) are most naturally read, as carrying implications about what is not possible for the speaker to recommend or understand. This is apparent from the fact that in their naturally occurring contexts, (34a) follows a report on recommendable cassette tape brands and (34b) follows remarks in which the speaker concedes that there is a range of understandable reactions.Footnote 7

How do intuitions about (32) compare to the relevant predictions under Müller’s proposal? Recall that under this proposal, a structure like (19) is obligatorily mapped to (29), so that NEG extension amounts to negation scoping globally in its clause. With global negation scope, the exclusive particle could in principle scope above or below the modal verb müssen (‘must’). The structure in (29) therefore predicts that (32) has one or both of the readings in (35).

-

(35)

-

a.

“Global NEG” (unavailable)

It is not required that only the FOX knock on the door.

-

b.

“Global NEG” (unavailable)

It is not only required that the FOX knock on the door.

-

a.

However, intuitions are crisp that (32) cannot in fact be read in such a way. This can be seen by observing that both statements in (35) are compatible with the assumption that the fox is required to knock on the door, and that this assumption is intuited to be incompatible with the truth of (32).Footnote 8 For example, (32) clearly cannot be understood as being true in a scenario where both the fox and the rabbit are required to knock, despite the fact that both (35a) and (35b) are true in such a scenario. We conclude that (32) does not allow for global NEG scope. Likewise, global NEG scope seems out of the question for the naturally occurring examples in (34).

So, when applied to a high remnant VP in the prefield modified by negation, node removal plus reassociation overgenerates, predicting unattested global NEG meanings. To prevent this overgeneration, we must therefore put to rest the idea floated above that a structure of the form in (29) can pass as well-formed despite negation’s inability to occupy SpecC in baseline data like (30).

Under the remnant movement analysis of NEG extension, then, we after all have no choice but to reject Müller’s strong hypothesis that unbound traces must invariably be eliminated in a derivation’s final output structure. NEG extension must be sourced in remnant movement structures like (19), where the modal’s unbound trace remains present. Therefore, node removal plus reassociation cannot be obligatory.

What we will see in the next subsection is evidence for a stronger point. In certain data, node removal plus reassociation would yield an unattested meaning even though the output structure should be well-formed. This will lead to the conclusion that under certain conditions, at least, node removal is not merely not obligatory, but in fact is not even allowed.Footnote 9

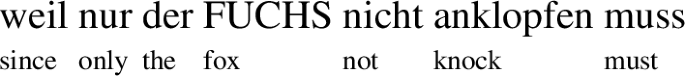

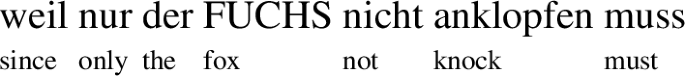

Before turning to this point, though, let us make sure that the range of intuited possible meanings of (32) is understood once we assume that there is no obligatory process of node removal and reassociation. To see that this assumption indeed renders the range of observed scope orders unsurprising, consider example (36).

-

(36)

This sentence is the V-final counterpart of (32). The finite modal muss now sits in the right bracket, and the sequence that occupies the prefield in (32), nicht anklopfen, instead appears between the subject nur der FUCHS and the finite modal. The relevant observation is that the range of scope orders intuited for (36) matches the one intuited for (32). That is, (36) allows for high or low NEG relative to the modal within the scope of nur, as in (33a) or (33b), but strictly resists a reading where negation scopes globally, as in (35a) or (35b). The scope orders attested for (32) could therefore be understood as a consequence of the generalization that the derivation of a V2 sentence with VP fronting does not expand the range of scope options available in the corresponding V-final structure. Setting aside node removal and reassociation, there is in fact no reason to expect such an expansion of scope options. In particular, under any extant notion of reconstruction (e.g., Sauerland and Elbourne 2002), expansion of scope options in the relevant V2 cases would be precluded under the plausible assumption that the fronted VP in SpecC and the finite V in C obligatorily reconstruct.

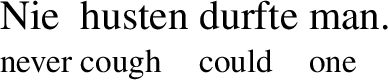

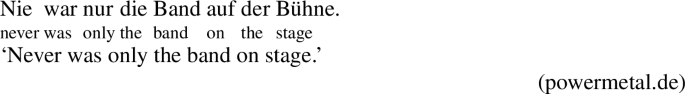

4.2 Optional restructuring and overgeneration

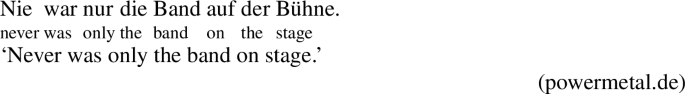

The negative AdvP nie (‘never’) can be shown to participate in the kind of NEG extension described above for nicht (‘not’). For example, in parallel to (14), sentence (37) can be understood as conveying the low NEG reading in (38b), but also seems to allow for NEG extension, that is, for the high NEG reading in (38a). The existence of NEG extension with nie is further confirmed by the naturally occurring examples in (39). From the content of these sentences, it seems evident that each was intended in a reading where negation scopes over the modal in the left bracket.Footnote 10

-

(37)

-

(38)

-

a.

“High NEG” (available)

One was never allowed to cough.

-

b.

“Low NEG” (available)

One was allowed to never cough.

-

a.

-

(39)

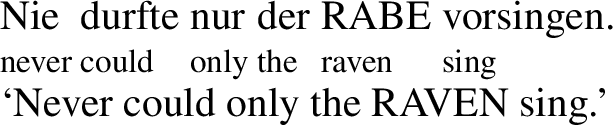

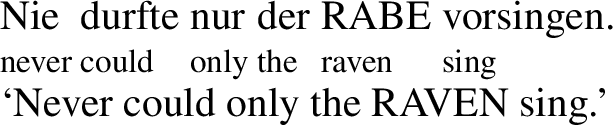

At the same time, there is an important difference in distribution between nicht and nie. In contrast to nicht, nie is fully acceptable as the sole occupant of a V2 sentence’s prefield, SpecC. This distributional property, which is typical for adverbials, is illustrated in (40).

-

(40)

Given this, NEG extension data with nie offer an opportunity for investigating the status of the process of node removal plus reassociation. If this process, even if not obligatory, can always optionally apply as long as its output is well-formed, then its effects should be observable in cases of NEG extension with nie. That is, with NEG now instantiated by nie, we should be able to observe the effect of a derivation that applies node removal and reassociation to an instance of the structure (19), outputting a well-formed instance the structure in (29).

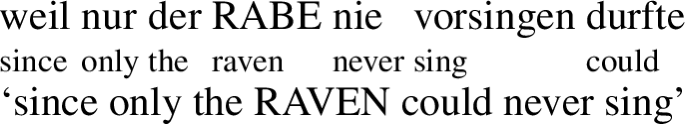

In this output structure, nie would c-command the remainder of its clause. What would be predicted, therefore, is that in contrast to NEG extension with nicht, NEG extension with nie can give rise to global NEG readings in cases with an additional scope bearing operator in the middle field. This prediction indeed seems inescapable, since cases where nie appears in the prefield on its own allow for global NEG scope. For example, the author of (40), reporting on a rowdy concert with stage-diving fans, undoubtedly intended a reading where nie outscopes the occurrence of exclusive nur in the middle field. Likewise, example (41), which features the modal verb dürfen (‘may,’ ‘be allowed’) in the left bracket, allows for nie to be interpreted with scope over both the modal and nur.

-

(41)

In fact, two such readings can be detected for (41), which are paraphrased in (42). Within nie scoping globally, (41) can be read with nur scoping above the modal, as in (42a), or below the modal, as in (42b).

-

(42)

-

a.

“Global NEG”

Never was the raven the only one who was allowed to sing.

-

b.

“Global NEG”

Never was it allowed for the raven to be the only one to sing.

-

a.

This confirms that when c-commanding the remainder of its clause in surface structure, nie can be interpreted as taking global scope. Therefore, if it is assumed that node removal and reassociation are processes that can optionally apply to remnant movement structures, there seems to be no escape from the prediction that NEG extension with nie enables global NEG scope.

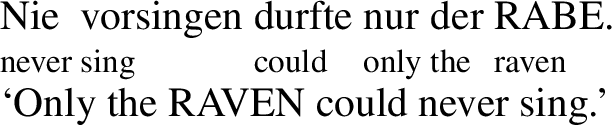

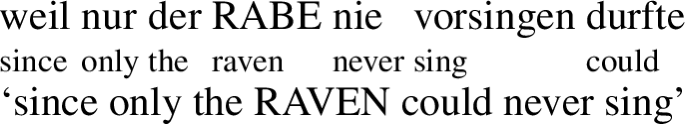

But this prediction is incorrect. NEG extension with nie does not enable global NEG scope any more than NEG extension with nicht does. Consider the word order variant of (41) in (43). This sentence is structurally isomorphic to the nicht example (32) above in that nie is accompanied in the prefield by the lower segment of a nested VP, and this lower VP is the complement of a higher modal that appears in the left bracket.

-

(43)

Sentence (43) is intuited to permit the two readings paraphrased in (44). These are parallel to the readings for (32) given in (33). So they have in common that the exclusive particle is interpreted with global scope, and they differ with regard to the relative scope of NEG and the modal. In (44b), the modal outscopes NEG, resulting in the implication that the raven was allowed to never sing, hence was never required to do so. In contrast, NEG extends its scope over the modal in (44a), yielding the implication that the raven was never allowed to sing, hence always required not to do so.Footnote 11

-

(44)

-

a.

“Non-global high NEG” (available)

The raven was the only one who was never allowed to sing.

-

b.

“Low NEG” (available)

The raven was the only one who was allowed to never sing.

-

a.

Given that (43) has the NEG extension reading (44a), the prediction that NEG extension enables global NEG scope here amounts to the prediction that (43) also permits a reading where nie scopes over both nur and the modal. So (43) should allow for at least one of the two readings in (42), readings that we saw can in fact be expressed by sentence (41). However, in sharp contrast to (41), intuitions are clear that (43) cannot have either of these meanings. This can be established with the observation that, while both statements in (42) are compatible with the assumption that the raven was always required to sing, sentence (43) clearly cannot be read as being compatible with this assumption. Assuming the remnant movement analysis of NEG extension, then, intuitions about NEG scope are incompatible with the assumption that the processes of node removal and reassociation can always optionally apply as long as their output structure is well-formed.

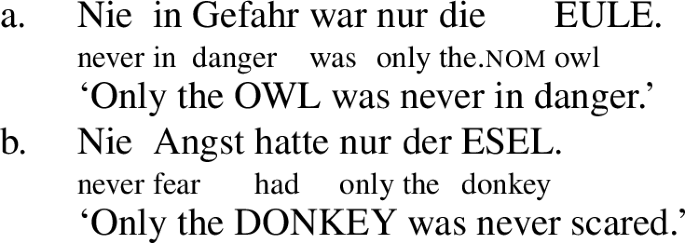

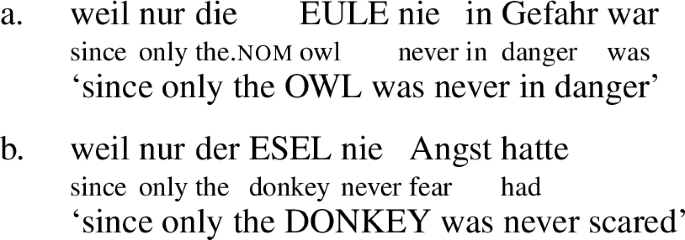

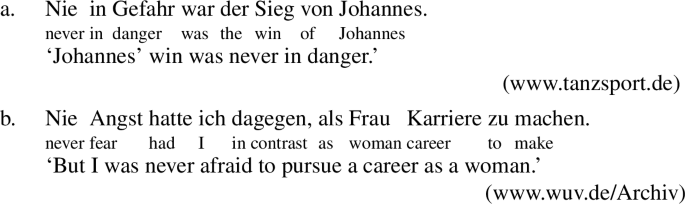

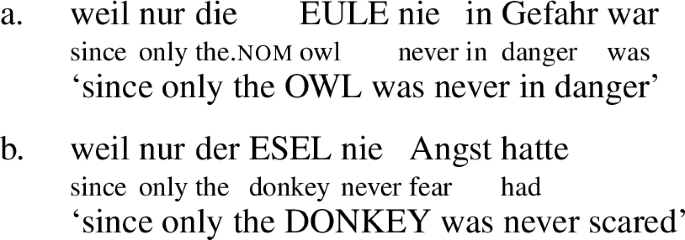

There is an alternate route to this same conclusion, one that does not reference intuitions about NEG extension or the analysis of NEG extension in terms of remnant movement. Assuming the remnant movement analysis of apparent V3, the argument can be recreated with cases of apparent V3. To set the stage, consider the naturally occurring main clauses in (45), where the prefield features nie followed by a PP (in Gefahr ‘in danger’) or an NP/DP (Angst ‘fear’).

-

(45)

These examples are cases of apparent V3 in so far as there is no credible parse where the AdvP nie merges with a PP or NP/DP. Under the remnant movement analysis of apparent V3, therefore, the prefield in these cases is to be parsed as a VP with a silent verbal head. So, here again the assumption that grammar allows for node removal and reassociation predicts structures where nie c-command the remainder of its clause.

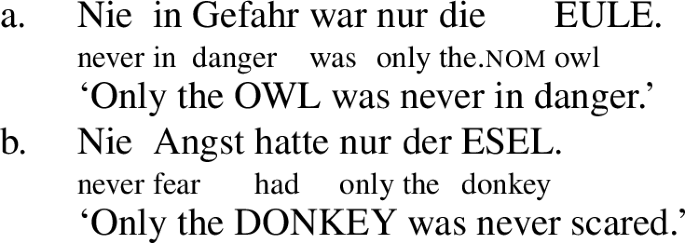

The same is true for the constructed examples in (46), which feature the same prefields as the sentences in (45), and in addition contain a scope bearing operator in the middle field, viz. once again the exclusive particle nur.

-

(46)

Under the remnant movement analysis of apparent V3, the assumption that grammar allows for node removal and reassociation would yield the prediction that the examples in (46a) and (46b) allow for global NEG scope readings, viz. (47a) and (47b), respectively. This prediction is again hard to avoid, given intuitions about cases where nie appears in the prefield on its own. Aligned with the observations about (40) and (41) above, the variants of the examples in (46) shown in (48) clearly do permit the readings in (47).

-

(47)

-

a.

“Global NEG”

Never was the owl the only one to be in danger.

-

b.

“Global NEG”

Never was the donkey the only one to be scared.

-

a.

-

(48)

Yet, once again, the prediction is incorrect. Apparent V3 order with nie does not enable global NEG scope any more than NEG extension with nie does. In stark contrast to the sentences in (48), the examples in (46) clearly cannot have the global NEG readings in (47). The statements in (47) are compatible with the owl or donkey having been scared or in danger at all the relevant points in time. But the sentences in (46) are clearly intuited to imply that they never were, indicating that these sentence resist global NEG readings, and only permit readings where nie scopes below only, readings that are paraphrased in (49).

-

(49)

-

a.

“Low NEG”

The owl was the only one to never be in danger.

-

b.

“Low NEG”

The donkey was the only one to never be scared.

-

a.

So just like scope intuitions about NEG extension data, scope intuitions about apparent V3 cases are in conflict with the hypothesis that node removal and reassociation are generally available optional processes, processes that can always apply to remnant movement structures as long as this leads to a well-formed output.

On the other hand, again paralleling the earlier findings with nicht data, if node removal and reassociation are assumed not to be applicable to the NEG extension and apparent V3 data with nie presented above, then the relevant scope intuitions are unsurprising. This is so because the scope options intuited for the examples in (43) and (46) are the same as those intuited for the V-final counterparts of those sentences. That is, sentence (50) permits the readings in (44) but not those in (42), and likewise the sentences in (51) have the readings in (49) but not those in (47).

-

(50)

-

(51)

So as soon as one abandons the assumption that node removal and reassociation can apply to the NEG extension and apparent V3 examples with nie presented here, the range of observed scope orders can be made to follow from the unexceptional assumption already appealed to above, viz. that a the derivation of a V2 sentence where VP is fronted to the prefield does not expand the range of scope options available in the corresponding V-final structure.

5 Concluding remarks

To summarize, in cases where negation marks the left edge of a lower VP within the prefield, negation may nevertheless be understood as scoping over the higher VP. This is naturally explained under assumptions that have been made in the remnant movement approach to apparent V3. The negation scope data therefore provide novel support for this approach to apparent V3. At the same time, however, we saw that the scope data are inconsistent with Müller’s (2018) proposal that the remnant VPs posited under the approach must always be reconfigured through node removal and reassociation in order for the output structure to be well-formed. In fact, we saw that the scope data are even inconsistent with the assumption that such reconfiguration is always an option. We saw data where under the remnant movement analysis, scope intuitions indicate that the prefield hosts a remnant VP with a silent head, while indicating at the same time that removal and reassociation cannot apply.

What are we to conclude about the conditions under which node removal and reassociation can apply? A simple answer would be that these processes do not in fact apply under any conditions, as they do not actually exist in grammar. This answer has the intended effects for all the examples discussed above. To be sure, however, Müller (2018) provides extensive motivation for the proposal that these processes sometimes are at work in syntactic derivations, offering a host of data points that would at present remain unexplained in a theory that denies their existence. I will conclude by attending briefly to one of those data points, one that is of particular interest here in that it conflicts most directly with the findings above.

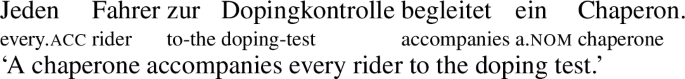

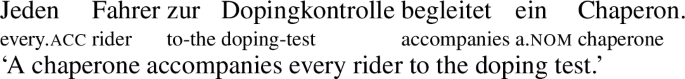

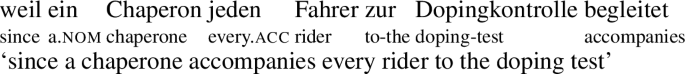

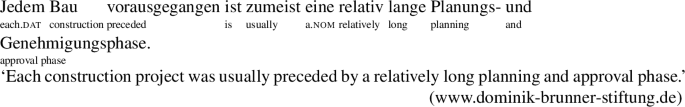

Müller discusses the intuited meaning of the apparent V3 example in (52), where the prefield features a sequence comprised of a DP and a PP, the universally quantified object DP jeden Fahrer (‘every rider’) and a directional PP zur Dopingkontrolle (‘to the doping test’). In addition, there is an indefinite subject in the middle field, ein Chaperon (‘a chaperon’).

-

(52)

Müller observes that (52) allows for a reading conveying that for every rider there is a chaperone who accompanies him to the doping test. So the universal object in the prefield can scope over the existentially interpreted indefinite subject in the middle field. Müller argues that this reading requires a surface structure where the universal object c-commands the indefinite subject, and specifically argues for a syntactic derivation of this c-command relation with node removal and reassociation. In Müller’s assessment, then, (52) supports the assumption that removal and reassociation can yield global scope for operators that would not otherwise be so interpretable.

It indeed seems beyond doubt that (52) permits a reading with wide scope for the universal object over the subject. But Müller’s interpretation of this judgment conflicts directly with what we concluded on the basis of examples with nie, in (43) and (46) above.

What might explain the contrast in intuited scope possibilities between (52) and the sentences in (43) and (46)? Why can the universal DP jeden Fahrer (‘every ride’) in (52) take wide scope over the existential indefinite, while at the same time global scope for nie in (43) and (46) is strictly unavailable? A possible clue comes from a comparison with the V-final versions of the relevant sentences. For the nie examples, the V-final versions were shown in (50) and (51). The V-final counterpart of (52) is given in (53).

-

(53)

The relevant observation is that the intuited scope options for (53) are the same as those for (52). In particular, despite following the indefinite in surface order, the universal object in (53) is naturally interpreted as taking wide scope. One might hope that this observation falls under an extended version of a generalization already appealed to above. It was suggested in Sect. 4 that the derivation of a V2 sentence where VP is fronted to the prefield does not add any scope options to those available in the corresponding V-final structure. Intuitions about scope (52) and (54) now suggest that such a derivation also does not remove any of the scope options that are available in the corresponding V-final structure.

If that was indeed the correct generalization, then the fact that the universal object in (52) can outscope the existential subject would not in fact support an argument for structure removal in a fronted VP. However, presenting the important control in (54) below, Müller expressly aims to exclude the possibility that fronting of a VP in the derivation of a V2 sentence guarantees the preservation of available scope relations.

-

(54)

This sentence differs from (52) only in that the fronted VP is headed by an overt past participle, begleitet (‘accompanied’), which in turn is selected by a finite auxiliary hat (‘has’) in the left bracket. This means that node removal and reassociation cannot apply to (54) to extend the c-command domain of the arguments in VP. While conceding that judgments are subtle, Müller reports that in this case the universal object indeed cannot be understood as scoping over the existential subject. If so, then without subsequent restructuring, fronting of the remnant VP in (52) would likewise be expected to eliminate the option of the universal object scoping wide. Assuming Müller’s judgment about (54), then, scope intuitions about (52) do after all support an argument for node removal and reassociation.

Considering the full set of relevant contrasts, then, what the scope data may call for is a more articulated theory of structure removal and reassociation, a theory that can explain why these processes can apply in some cases, such as Müller’s example (52), but not in others, such as the new data that this paper has drawn attention to.Footnote 12

Notes

In Wurmbrand (2007), scope data with negation (and other operators) are presented as an argument that German clause structure features nested VPs of the form shown in (6) in the first place, defending this assumption against the view that the relevant sequences are single-layer VPs projected by complex verb clusters (e.g., Haider 2010). Below I will present evidence against a particular generalization suggested by Wurmbrand about how word order constrains scope relations. Importantly, however, this evidence does not in any way undermine Wurmbrand’s main argument. In fact, accepting this argument as successful, it is simply taken for granted here that German indeed features nested VPs.

Conceivably, negation in (9) could be interpreted with widest scope in its clause if it was used contrastively, a use illustrated by B’s reply in the exchange in (i). Contrastive uses are characterized by contrastive pitch accents, here marked by capitalization, and they normally require a continuation with an adversative conjunction, like sondern (‘but’) in (i) (e.g., Jacobs 1982). The examples discussed in the main text are not of this sort, though, and I will disregard contrastive uses of negation without any further reminders.

-

(i)

-

(i)

Wurmbrand’s example features an additional operator, viz. the exclusive particle nur (‘only’). This additional operator does not actually seem to play a role in Wurmbrand’s argument, and it will likewise not play a role in the remainder of this section. However, attending to examples much like (9), Sect. 4 will crucially investigate the scopal interaction of negation contained within the prefield with an operator in the clause’s “middle field.”

The judgments underlying the arguments presented in this paper consist of two types of intuitions about scope. Type 1, illustrated with (14), is the intuition that in certain structures, negation can be interpreted as taking wide scope, over a modal. Type 2, which will only make its appearance in Sect. 4, is the intuition that negation cannot be interpreted as taking scope over a certain additional operator (viz. nur ‘only’). Type 2 intuitions, which I will illustrate with constructed examples, are in my estimation sharp and robust throughout. They were also confirmed by a native speaker consultant and accepted by two anonymous reviewers. My own intuitions of Type 1 are quite clear as well, but the native speaker consultant and one reviewer reported hesitations about some of my constructed examples. However, for nearly all Type 1 judgments reported in this paper, I provide naturally occurring examples where the relevant meaning was clearly intended by the author. For one specific profile of Type 1 data, though, my search for naturally occurring examples was unsuccessful, a gap flagged in fn. 11 below.

As a further illustration of the restrictedness of NEG extension, a reviewer reports finding a high NEG reading difficult to access for example (i), even though (i) differs from (14) merely in that the fronted VP contains the modifier am Gang (‘in the aisle’).

-

(i)

Under the present hypothesis, this suggests that a modifier in the prefield can sometimes be incompatible with the requisite information structural conditions on remnant movement. (That said, (16b) above, for example, illustrates that modifiers do not always have this effect.)

-

(i)

This argument is independent of the reasons for the ill-formedness of the (31) with NEG = nicht. The argument is compatible, in particular, with Zeijlstra’s (2013) proposal that (31) violates a restriction on scope relations. Zeijlstra suggests that a negative operator must not be interpreted with scope over an illocutionary feature assumed to occupy C, and that the surface form (31) necessarily yields a violation of this constraint, based on the assumption that fronted nicht cannot reconstruct.

The examples in (32) and (34a,b) contrast with Wurmbrand’s (2007) case in (9) above, which also features nur, but where a NEG extension reading seems unavailable. This presumably has to do with the fact that the modal in (9), sitting in the right bracket, follows the exclusive particle. Under the view articulated in Sect. 3, this order is for some reason incompatible with the information structural condition on remnant movement.

The two hypothetical readings might even be expected to imply that the fox is required to knock. In (35b), this implication is a presupposition that is expected to be triggered by the exclusive particle and to project past negation (cf. Horn 1969). In (35a), it is the expected result of triggering plus projection from under negation and the necessity modal (e.g., Heim 1983, 1992).

Müller (2018: fn. 29) points out that the view of node removal as an optional process is too weak to capture some of the intended results he discusses (under the headings “freezing effects,” “left dislocation,” and “extraposition”). The point to be made below goes in the opposite direction, suggesting that even this weak hypothesis is an obstacle to understanding restrictions on scope.

Nie can plausibly participate in the sort of scope splitting that negative indefinite nominals in German are known to permit (see, e.g., Zeijlstra 2020 and literature cited there). That is, it is plausible that a modal operator can be read as scoping below the logical negation introduced by nie but above the associated existential quantifier over times. If so, then there might in particular be NEG extension parses that encode this scope order. However, I will disregard such scope splitting parses in the argument made below. This is safe to do because there are no reasons to expect that scope splitting would be obligatory in NEG extension with nie. As an optional process, scope splitting can merely extend the range of readings that arise in its absence, hence cannot be appealed to as a possible reason for the unavailability of a given meaning. Therefore, reference to scope splitting cannot help one evade the overgeneration problem that will be introduced below, that is, the problem that node removal and reassociation predict unattested meanings. Setting aside scope splitting, the main text will for ease of exposition continue to identify NEG with nie as a whole, viewed as an operator that encodes negated existential quantification.

I have not been able to find naturally occurring examples with the same profile as (43), hence no naturally occurring instances of NEG extension with nie interpreted in the scope of an occurrence of nur in the middle field. However, for the overgeneration argument developed here, this limitation is mitigated by the apparent V3 data in (46) below, which serve as an additional empirical foundation for this argument.

This conclusion is not invariably aligned with German speakers’ scope intuitions, however. In my own judgment, wide scope of the universal is possible in (54), in fact no less so than in (52). Notably, such variation in judgments is interesting in its own right, as it bears on the adequacy of “Barss’ generalization” (Barss 1986), which holds that in the structure in (i), γ cannot be interpreted with scope over β.

-

(i)

Since (54) instantiates (i), with jeden Fahrer = γ and ein Chaperon = β, Müller’s intuitions about (54) are aligned with Barss’ generalization, as Müller indeed points out. Not so for my own intuitions about (54), though, and a broader survey of data confirms that Barss’ generalization surely requires qualification. Sentence (ii) below, for example, is most certainly intended in a reading where the universal object (jedem Bau = γ) scopes over the existential indefinite subject in the middle field (eine …Genehmigungsphase = β), allowing for the sentence to be true in realistic scenarios where the planning and approval phases varied with the construction projects.

-

(ii)

-

(i)

References

Barss, Andrew. 1986. Chains and anaphoric dependence. PhD diss, MIT.

Bildhauer, Felix, and Philippa Cook. 2010. German multiple fronting and expected topic-hood. In Headdriven phrase structure grammar (HPSG 17), ed. Stefan Müller, 68–79. Stanford: CSLI.

den Besten, Hans, and Gerd Webelhuth. 1990. Stranding. In Scrambling and barriers, eds. Günther Grewendorf and Wolgang Sternefeld, 77–92. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Fanselow, Gisbert. 1993. Die Rückkehr der Basisgenerierer. Groninger Arbeiten zur germanistischen Linguistik 36: 1–74.

Haider, Hubert. 2010. The syntax of German. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Heim, Irene. 1983. On the projection problem for presuppositions. In Proceedings of the second West Coast Conference in Linguistics, eds. D. Flickinger, M. Barlow, and M. Wescoat, 249–260. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Heim, Irene. 1992. Presupposition projection and the semantics of attitude verbs. Journal of Semantics 9(3): 183–221. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/9.3.183.

Horn, Laurence. 1969. A presuppositional analysis of only and even. In Papers from the 5th meeting of the Chicago Linguistics Society, Vol. 5, 98–107. Chicago: Chicago Linguistics Society.

Jacobs, Joachim. 1982. Syntax und Semantik der Negation im Deutschen. München: Fink.

Jacobs, Joachim. 1983. Fokus und Skalen. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Jäger, Agnes. 2008. History of German negation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins.

Müller, Gereon. 1998. Incomplete category fronting. Norwell: Kluwer Academic.

Müller, Gereon. 2018. Structure removal in complex prefields. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 36(1): 219–264.

Müller, Stefan. 2005. Zur Analyse der scheinbar mehrfachen Vorfeldbesetzung. Linguistische Berichte 203: 297–330.

Müller, Stefan. 2015. German clause structure: An analysis with special consideration of so-called multiple frontings. Berlin: Language Science Press.

Sauerland, Uli, and Paul Elbourne. 2002. Total reconstruction, PF movement, and derivational order. Linguistic Inquiry 33(2): 283–319.

Thiersch, Craig. 2017. Remnant movement. In The Wiley Blackwell companion to syntax, second edition, 1–77. New York: Wiley.

Wurmbrand, Susi. 2007. How complex are complex predicates? Syntax 10(3): 243–288.

Zeijlstra, Hedde. 2013. Not in the first place. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 31(3): 865–900.

Zeijlstra, Hedde. 2020. Negative quantifiers. In The Oxford handbook of negation, 426–440. London: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198830528.013.13.

Acknowledgements

For comments, questions, and discussion, I thank Alexander Göbel, Kyle Johnson, Michael Wagner, the handling editor Hedde Zeijlstra, and two anonymous reviewers. All errors are, of course, my own.

Funding

This research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (Insight Grant # 435-2019-0143).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The author has no conflict of interests, financial or non-financial, relating to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schwarz, B. Structure preservation in complex prefields: A note on Müller (2018). Nat Lang Linguist Theory 41, 1563–1587 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-023-09571-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-023-09571-8