Abstract

A major challenge for event structural theories that decompose verbs into event templates and roots relates to the syntactic distribution of roots and what types of event structures roots can be integrated into. Ontological Approaches propose roots fall into semantic classes, such as manner versus result, which determine root distribution (Rappaport Hovav and Levin 1998, 2010). Free Distribution Approaches, in contrast, hold that root distribution is not constrained by semantic content and roots are free to integrate into various types of event structures (Borer 2005; Acedo-Matellán and Mateu 2014). We focus on two different classes of verbs classified as result verbs in Rappaport Hovav and Levin’s (1998, 2010) sense and their ability to appear in resultative constructions. We build on Beavers and Koontz-Garboden’s (2012, 2020) proposal that the roots underlying these verbs fall into two classes: property concept roots, which denote relations between individuals and states, and change-of-state roots, which on our proposal, denote relations between individuals and events of change. We show that change-of-state roots, but not property concept roots, are able to appear in the modifier position of resultative constructions by providing naturally occurring examples of such resultatives. Combining the proposed lexical semantics of these two classes of roots with a reformulation of an Ontological Approach solely dependent on a root’s semantic type, we show that this analysis makes novel and accurate predictions about the possibility of the two classes of roots appearing in resultative constructions and the range of interpretations available when change-of-state roots are integrated into resultative event structure templates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Event structural theories of verb meaning propose that verbs consist of event structure templates, which define the temporal and causal structure of the event, and roots, which provide real-world information about the event (Dowty 1979; Rappaport Hovav and Levin 1998, 2010; among many others). Major concerns for such theories include the distribution of idiosyncratic roots and what sorts of event structures particular roots can be integrated into, as it seems clear roots appear in different event structures (cf. John died and *John died the man vs. John destroyed the city and *The city destroyed).

One proposed influential answer to this challenge suggests that roots fall into clear ontological classes according to their semantic content, which in turn determines what event structures they can be integrated into (e.g., Marantz 1997; Rappaport Hovav and Levin 1998; Harley and Noyer 1999, 2000; Embick 2004, 2009; Harley 2005; Alexiadou et al. 2006; Levinson 2014; Alexiadou et al. 2015). For example, Rappaport Hovav and Levin (1998, 2010) argue for a distinction between manner and result verbs, with the roots of each class containing complementary semantic entailments and each compatible only with particular event structure templates, leading to a Manner/Result Complementarity, as defined in (1).

-

(1)

Manner/Result Complementarity: Manner and result meaning components are in complementary distribution. A verb lexicalizes only one.

On the other end of the spectrum is the view that roots are actually devoid of any semantic information relevant to determining their syntactic distribution (e.g., Arad 2003, 2005; Borer 2003, 2005, 2013; Acquaviva 2008, 2014; Mateu and Acedo-Matellán 2012; Acedo-Matellán and Mateu 2014). These approaches predict that any root can in principle appear in any event structure, since roots are not constrained in terms of the syntactic contexts they are compatible with. Henceforth, we term the first class of approaches the Ontological Approach and the latter the Free Distribution Approach, following Rappaport Hovav (2017).

We demonstrate that the two main approaches to event structure as described above do not accurately predict the range of event structures that the roots of result verbs (henceforth, result roots) in Rappaport Hovav and Levin’s (2010) sense can appear in.Footnote 1 In particular, we examine the possibility of result roots occurring in resultative constructions, where the manner and result components are named by different roots, e.g., John wiped the table clean (Hoekstra 1988; Carrier and Randall 1992; Kratzer 2005; amongst others). On approaches assuming Manner/Result Complementarity, result roots are predicted to be illicit if they name the manner and not the result component. Only the roots of manner verbs should appear in resultative constructions as specifiers of the manner component, as the example below shows.

-

(2)

We show, however, that the picture presented in (2) is not completely accurate. There is indeed a sub-class of result roots that never appear as the manner component of resultative constructions, contradicting the Free Distribution Approach. However, there is also a second sub-class of result roots that does in fact appear in resultative constructions in which there is a separate constituent contributing a result state. An example of a naturally occurring example, containing a canonical result root that forms the surface verb tear in a resultative construction, is illustrated below.

-

(3)

We compile a list of further naturally occurring examples, which we examine in detail and also provide in the appendix. This observation in turn contradicts an Ontological Approach built on Manner/Result Complementarity, as the result root appears to name the manner component of the event, while the result is named by the adjective free. It is worth emphasizing that these data are naturally occurring, since it has often been claimed in the literature that such uses of result roots in resultative constructions are unacceptable (Rappaport Hovav and Levin 1998, 2010; Rappaport Hovav 2014; Levin 2017). Specifically, we extract the naturally occurring examples presented here from different corpora: Google Books (GBooks), Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) (Davies 2008), Corpus of Web-Based Global English (GloWbE) (Davies 2013), and web searches (Web). Given that such uses of result roots are naturally attested, the theoretical aim of this paper is to provide an explicit, compositional semantics for these two classes of result roots that explains their distribution in resultative constructions, while also addressing the range of acceptability judgments in the literature surrounding such uses of result roots.

We follow Beavers and Koontz-Garboden (2020) in distinguishing two sub-classes of result roots. The first class of result roots are property concept roots (Dixon 1982, 2004; Francez and Koontz-Garboden 2017; Beavers and Koontz-Garboden 2020), which we analyze as relations between individuals and states. Deadjectival result verbs are derived from this root class, and involve property concepts related to dimension, e.g., widen, shorten; color, e.g., redden, whiten; physical properties, e.g., strengthen, harden; etc. (see Dixon 2004). By virtue of being stative, they never occur as the manner component in resultative constructions, as shown in (2b). This fact is consistent with an Ontological Approach built on Manner/Result Complementarity, but not with a Free Distribution Approach. On the other hand, a second sub-class of result roots enjoys a certain level of elasticity, as they appear to occur in the manner position in resultative constructions in naturally occurring English data, as in (3), seemingly contradicting Manner/Result Complementarity and consistent with a Free Distribution Approach. This sub-class, which we call change-of-state roots, entails a transition to the state that the root names, unlike property concept roots, which do not in and of themselves entail change (Beavers and Koontz-Garboden 2020). Canonical instances of verbs derived from this root class include e.g., break, burn, split, tear, rip. Departing from Beavers and Koontz-Garboden (2020), we analyze these roots as relations between individuals and events of change into the result state the root names. Combined with a strict mapping between the semantic types of result roots and the event structural position in which a given root is integrated (e.g., Folli and Harley 2005; Embick 2009; Levinson 2014), we arrive at an Ontological Approach dependent strictly on type-theoretic properties of root classes, rather than on manner versus result entailments. This approach makes novel and accurate predictions about the distribution of result roots in resultative constructions, as well as the range of interpretations available when change-of-state roots are integrated into a resultative event structure template in our naturally occurring data. In turn, the analysis sheds more light on the status of Manner/Result Complementarity. Specifically, we defend a view where Manner/Result Complementarity serves as a useful descriptive device for describing possible verb meanings, but does not strictly translate to distinct positions within an event structure template in the way originally proposed by Rappaport Hovav and Levin (1998, 2010), and therefore does not predict the distribution of result roots in resultative event structures. Rather, it is a root’s status as either eventive or stative that determines its position in an event structure template, independent of its manner or result entailments.

The paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we provide the empirical evidence that result roots can be broadly divided into two classes of roots based on whether they appear in resultative constructions or not, detailing as well patterns of interpretations when they do appear in such constructions. In Sect. 3, we provide lexical semantic denotations for these two distinct classes as well as a compositional syntax and semantics for their integration into event structure templates. We discuss how our analysis makes accurate predictions regarding the range of interpretations available when change-of-state roots are integrated into a resultative event structure template. In Sect. 4, we review previous analyses and how they might account for the two sub-classes of result roots, arguing that these approaches make inaccurate predictions or are silent on the interpretations we observe in the naturally occurring data. Section 5 concludes the paper.

A terminological clarification and notational issue are in order before we proceed. The reader may note that we differentiate between the terms verb and root. Throughout the paper, we use verb when discussing the surface verb, occurrences of which we consistently italicize in-text. On the other hand, we use the term root to reflect a theoretical construct common in frameworks like Rappaport Hovav and Levin’s (1998, 2010) event structure templates or in Distributed Morphology (Halle and Marantz 1993; Pesetsky 1995), where they provide idiosyncratic, real-world information to an event structure template or verbal functional structure. We adopt this style of analysis throughout, focusing specifically on the lexical semantics of roots, which form the surface verb by being embedded in an event structure or verbal functional structure. Second, the example in (2b) is notated with *, the standard notation for syntactic ungrammaticality as originally gleaned from the cited source. In our approach, this is motivated by a type-theoretic mismatch between the semantic type of the property concept root and that of the position in the resultative event structure it appears in, indicating that such a structure cannot be derived. In contrast, we notate some cases containing result roots in resultative event structures with #, indicating semantic anomaly in that the resultative construction in question cannot describe the particular context we pair it with, though from a compositional semantic point of view it is derivable with no type mismatches. This will become clear after the presentation of the analysis; we consistently use * and # in the ways just described for the examples we construct, though we reproduce the relevant notations from cited examples to remain faithful to these works.

2 Resultatives and the distribution of result roots

The two approaches to event structure and the distribution of roots discussed in the previous section make distinct predictions regarding the argument structure and realization patterns of verbal roots. Ontological Approaches like the one in Rappaport Hovav and Levin (1998, 2010) constrain manner roots to always be associated with the event structure as modifiers of the act operator as in (4). In contrast, result roots serve as complements of the become operator in (5) (see also Dowty 1979). Rappaport Hovav and Levin (1998, 2010) propose this is motivated by the complementary semantic entailments of manner or result, which have consequences for the integration of roots into event structures. Taking manner and result as basic ontological types, Rappaport Hovav and Levin thus propose that a root’s ontological type determines how it associates with a given event structure template.

-

(4)

John wiped.

[John act <WIPE> ]

-

(5)

The vase broke.

[The vase become <BREAK>]

Subsequent work in the Distributed Morphology tradition (e.g., Marantz 1997; Embick 2004; Folli and Harley 2005) builds on this semantic classification and proposes a syntactic implementation of it. Manner denoting roots are modifiers of functional verbalizing heads encoding eventive semantics like causation, where the root merges directly with a little v head to form a complex v. In contrast, result denoting roots are complements of eventive verbalizing heads and define the result state arising from these events (Embick 2004; Folli and Harley 2005; Harley 2005, 2012; Alexiadou et al. 2015, amongst others, especially see Sect. 3 for details). Free Distribution Approaches on the other hand predict that any root can in principle be both a modifier or a complement in different constructions, since roots are not assumed to have any grammatically relevant semantic content that can determine their distribution in event structure templates. On this view, roots are thus not constrained in terms of the syntactic contexts they can occur in by their semantics and can in principle appear in any syntactic context. Syntactic and semantic properties of roots are therefore exclusively determined by the event structure templates. A prediction of this approach is that the same root can be associated with distinct semantic interpretations as well as distinct syntactic properties, depending on the event structure template the root occurs in.

Here, we consider these predictions with respect to resultative constructions, e.g., hammer the metal flat. These constructions provide an ideal testing ground for these predictions because they have an event structure in which the manner (modifier) and result (complement) components can be named separately by different roots. Under a syntactic implementation of the split between manner and result roots, these are analyzed as having two distinct roots within a causative event structure; a manner root is adjoined directly to vcause, specifying the manner in which the causative event was carried out, while the result root serves as the complement to the complex head formed by the manner root and vcause, specifying the result state that is caused by this event (e.g., Hoekstra 1988; Folli and Harley 2005; Mateu 2012; Beavers and Koontz-Garboden 2020; Hopperdietzel 2022, amongst others).

-

(6)

Mary hammered the metal flat.

Examining the distribution of result roots in these constructions can therefore tell us which of the predictions of the above approaches are borne out. Crucially, we observe that neither approach is fully predictive of the distribution of result roots based on naturally occurring resultative constructions.

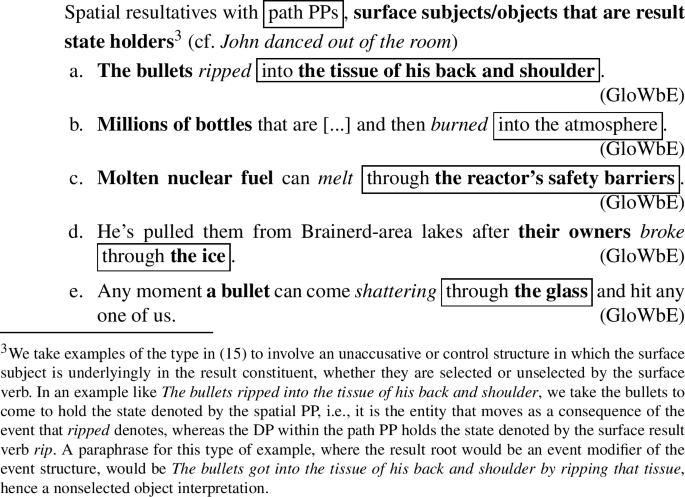

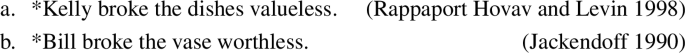

Rappaport Hovav and Levin’s Manner/Result Complementarity predicts that what they classify as result roots should be impossible in constructions where the result roots have to be integrated as modifiers. There is indeed a sub-class of result roots that show such a restriction; we illustrate here with the surface result verbs dim, thin, and cool, in contrast with canonical surface manner verbs scrub, hammer, and laugh. This contrast is observed across a range of different resultative constructions. (7) involves canonical instances of unselected object constructions in which the surface object is not subcategorized by the surface verb but comes to hold the result state denoted by the result phrases (i.e., her fingers are what become raw in (7a)). (8) shows a similar contrast in resultatives with selected objects, in which the surface object appears to be subcategorized by the surface verb. (9) involves what Jackendoff (1990) calls spatial resultatives in which the referent of the surface object undergoes a change of location encoded in a prepositional phrase. We provide as well Rappaport Hovav and Levin’s (1998) corresponding analysis in terms of event structure templates. As indicated by the judgments of the (b) sentences gleaned from the literature, these are consistently judged as unacceptable.

-

(7)

Resultatives with unselected objects

-

(8)

Resultatives with selected objects

-

(9)

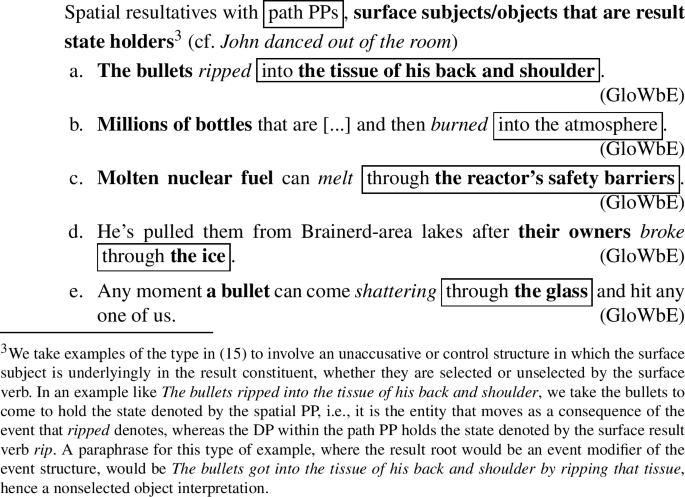

Spatial resultatives

In principle, it is possible to imagine the events described by the (b) examples. Nonetheless, Rappaport Hovav and Levin claim that it is impossible to describe such events with these structures, leading them to conclude that this is an actual grammatical constraint (see also Grimshaw 2005). Under Rappaport Hovav and Levin’s approach, the contrast above is accounted for; the (b) examples are ungrammatical because the result root is associated with the event structure as an event modifier. This is incompatible with the result entailments of such a root. The split in the data above between manner and result roots is thus compatible with an Ontological Approach based on Manner/Result Complementarity. Free Distribution Approaches would struggle to account for these contrasts, given that the events described by the ungrammatical examples above are in principle conceptually possible and yet these resultative constructions are unacceptable.

However, we observe that there is also a sub-class of result roots as classified by Rappaport Hovav and Levin that appear as modifiers and not as complements in resultative constructions, in contrast to what would be expected under Manner/Result Complementarity and an Ontological Approach built on it. The following naturally occurring examples involve the surface result verbs break, tear, rip, split, melt, shatter, burn (more examples are provided in the Appendix; see also Ausensi and Bigolin 2021).Footnote 2 In these cases, a separate root or phrase describes the result state of the event, while the result roots in question are integrated into the event structure as event modifiers.

-

(10)

-

(11)

-

(12)

-

(13)

-

(14)

-

(15)

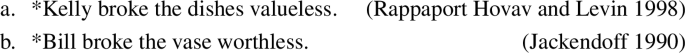

We emphasize that these are naturally occurring examples, since previous work often assert that examples like those above are ungrammatical. For example, verbs like break, burn, and freeze have been claimed to be ungrammatical with resultatives containing both unselected objects (16) and selected objects (17), and also in spatial resultatives (18).

-

(16)

-

(17)

-

(18)

An important question that arises then is what the differences between these two classes of examples might be. For example, why is broke his hands bloody judged unacceptable in the literature while broke the corpse loose from the deck is attested naturally? Similarly, regarding spatial/path PPs, what seemingly rules out burned into the hotel, at least according to Jackendoff (1990), while burned into the atmosphere is attested as well? Before laying out our analysis, an intuitive and informal explanation is that these unexpected APs or PPs either:

-

i.

Specify that the result state held by an unselected object was caused by an event in which some other, unexpressed object has come to hold the result state named by the root (10) (e.g., With a few slices of her claws, she tore him free).

-

ii.

Provide a DP that comes to hold the state named by the result root even if the surface object is unselected (14) (e.g., Scientists just melted a hole through 3,500 feet of ice) and (12) (e.g., splitting hydrogen out of water molecules).

-

iii.

Or describe a result state predicated of something of which the surface object is a part, whereby the surface object comes to be separated from the whole, e.g., (12a) (e.g., tore a piece off the letter).

Thus, break the corpse loose describes the corpse becoming loose of some structure that contains or binds it, and this freedom results from that structure breaking even if the structure is not overtly expressed. In melted a hole through 3500 feet of ice, the PP provides a DP 3500 feet of ice that melted, even though a hole is not interpreted as the theme of the verb melt but as a created object. Finally, tore a piece off the letter seems to intuitively indicate that the letter came to have a tear in it, which led to a piece of the letter being separated from it.

Ideally, we want an analysis that accommodates these interpretive patterns, since the naturally occurring data show that judgments of the data in (16–18) may not generalize. We also want to account for the existence of sub-classes of result roots, one of which does not appear in resultative constructions, while the other does. In what follows, we attempt to meet these challenges by providing a compositional semantic account of how one sub-class of result roots can be integrated into the event structure as modifiers, while another class of result roots resists such an integration and may only function as complements in the event structure.

3 Analysis

To account for the above observations, we propose a modified Ontological Approach to the distribution of result roots within resultative constructions that makes reference to the type-theoretic properties of roots, which constrains how they are integrated into particular event structure templates (Embick 2009; Levinson 2014). This is distinct from Manner/Result Complementarity; specifically, we claim that even if a root possesses result entailments, it can still be integrated as an event structure modifier if it is of the right semantic type. Building on a distinction developed by Beavers and Koontz-Garboden (2012, 2020), we distinguish two classes of roots that form result verbs: change-of-state roots, which denote relations between individuals and events, and property concept roots, which denote relations between individuals and states. We discuss these two classes in turn and how they come to be integrated into various event structures, including a resultative one, adopting a syntactic view whereby event structure is reflected directly in syntactic structure.

3.1 Sub-classes of result roots

The core of the proposal is to distinguish two sub-classes of result roots, what we will call change-of-state roots and property concept roots.Footnote 3 Change-of-state roots encode a change toward a particular result state named by the root. Examples of verbs formed from change-of-state roots include break, shatter, split, melt, burn, freeze etc. While Beavers and Koontz-Garboden (2012, 2020) provide an analysis of change-of-state roots as predicates of states entailing change, we depart from their approach in analyzing change-of-state roots as relations between individuals and events, such that the event in question is a transition into a state that the root names.Footnote 4 A change-of-state root like √break, for example, denotes a relation between an individual and an event of change, formally represented using the become operator (Dowty 1979), that leads to that individual being in a broken state (19).Footnote 5

-

(19)

〚√break〛: λx.λe.∃s[become(e,s) ∧ broken(x,s)]

In contrast, property concept roots form result verbs like open, close, straighten, cool, warm etc. The defining semantic property of this root class is that they do not lexically entail change, and are translated as relations between an individual and a state. An example of such a property concept root √open is provided below, which denotes a relation between an individual and a state of openness.

-

(20)

〚√open〛: λx.λs.open(x,s)

Notice that we use different variables for the final argument of these two classes of roots. A change-of-state root yields a property of events upon composing with its individual argument, indicated with the variable e whose description is a change event become. It also names the final state reached at the end of the change event as broken, indicated by the existentially quantified variable s. A property concept root, on the other hand, is a property of states after composing with its individual argument, indicated with the variable s, and does not entail any eventive change.

Adopting a syntactic approach to event structure in which little v heads are the locus of different event structure templates and also verbalize acategorial roots, we propose that the type-theoretic properties of these two classes of roots have consequences for how they are integrated into event structure templates (Marantz 1997; Embick 2004; Harley 2005; Embick 2009; Levinson 2014). In a simple transitive structure with a DP object like break the vase, the change-of-state root √break serves as the complement of an eventive v head vcause, encoding causative semantics represented by the semantic operator cause as in Kratzer (2005). The syntactic and semantic derivation of the vP excluding the external argument is illustrated below, where v is the type of events and t the type of truth values in the subscripts indicating the semantic type of vcause’s first argument.Footnote 6,Footnote 7

-

(21)

Lucy broke the vase.

Property concepts roots also serve as complements of vcause, with the caveat that they denote properties of states instead of properties of events. A syntactic and semantic derivation of the verb open is illustrated below. Note that vcause here composes with a property of states as its first semantic argument instead of a property of events as with roots like √break. The structure is entirely parallel to the simple transitive use of break, with only the denotations of the root differing across the two structures.Footnote 8

-

(22)

Kim opened the door.

Supporting evidence for distinguishing between property concept and change-of-state roots in terms of their stative or eventive nature comes from various sources. First, it is well known that the presupposition trigger again produces an ambiguity between repetitive and restitutive readings when modifying verbs formed out of property concept roots, as illustrated with open below (Dowty 1979; von Stechow 1996; Beck and Johnson 2004: amongst others).

-

(23)

John opened the door again.

The restitutive reading, involving restoration of a previous state, provides evidence that a stative constituent (RootP in (22)) must be available for again to target, triggering a presupposition of a prior identical state. The following examples from Beavers and Koontz-Garboden (2020: 85) further illustrate this with verbs formed out of property concept roots like √sharp, √long and √large; note that the contexts rule out any repetitive reading and thus indicate that the restitutive reading cannot be reduced to an entailment of the repetitive (von Stechow 1996; Beck and Johnson 2004; Lechner et al. 2015: amongst others)

-

(24)

In contrast to property concept roots, on our analysis there is no independent stative constituent that a sub-lexical modifier may target with change-of-state roots, as demonstrated with break in (21), where both vP and RootP are properties of events rather than states. We predict, then, that modifiers like again should not be ambiguous between a repetitive and restitutive reading with verbs like break. Even if again attaches to RootP in (21), this constituent denotes a property of events that entails a change-of-state because of the semantics of the change-of-state root; modification with again should therefore always produce an eventive, repetitive presupposition. As illustrated by Beavers and Koontz-Garboden (2020: 85) and Yu (2020), this prediction is indeed borne out (see also Rappaport Hovav 2008).

-

(25)

A second piece of evidence comes from internal readings of temporal for-phrases. It has long been noted that verbs formed from property concept roots allow for-phrases to measure the duration of their result state component to the exclusion of the causing event, what Dowty (1979) calls the internal reading. Such verbs also permit a durative reading, in which the for-phrase measures the duration of the change-of-state event.

-

(26)

Susan opened the door for two hours.

For Dowty (1979), this adds another piece of evidence in addition to modification by again that verbs formed out of property concept roots are decomposable into an eventive and stative component as in (22). Restitutive and internal readings of again and for-phrases are derived when these modifiers attach to the stative constituent. However, on our analysis, there is no such stative constituent with verbs formed from change-of-state roots like break in (21). The prediction then is that internal readings with for-phrases should be absent with these verbs, and only the durative reading should be available. This prediction is borne out, as can be seen in (27–29) below (see Ramchand 2008: 77–78 for discussion of the same observation).Footnote 9,Footnote 10

-

(27)

Susan broke the vase for 5 minutes.

-

a.

Susan spent 5 minutes breaking the vase, possibly by slowly chipping it apart.

-

b.

# Susan broke the vase, and the vase remained broken for 5 minutes before being repaired.

-

a.

-

(28)

Jill thawed the meat for 30 minutes.

-

a.

Jill spent 30 minutes thawing the meat, possibly by holding it over a hot stovetop.

-

b.

# Jill defrosted the meat instantly and left it thawed for 30 minutes before refreezing it.

-

a.

-

(29)

Johannes melted the cheese for 10 minutes

-

a.

Johannes spent 10 minutes melting the cheese, possibly by warming it on the stove.

-

b.

# Johannes melted the cheese quickly, and the cheese was in this melted state for 10 minutes before hardening again.

-

a.

3.2 Resultative constructions

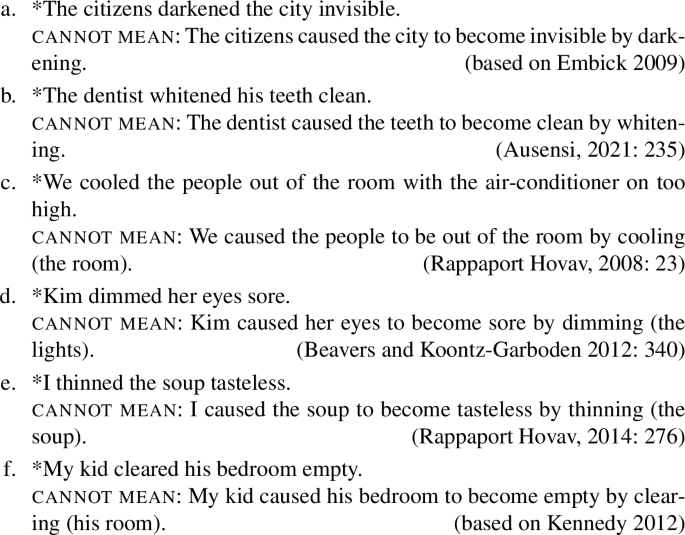

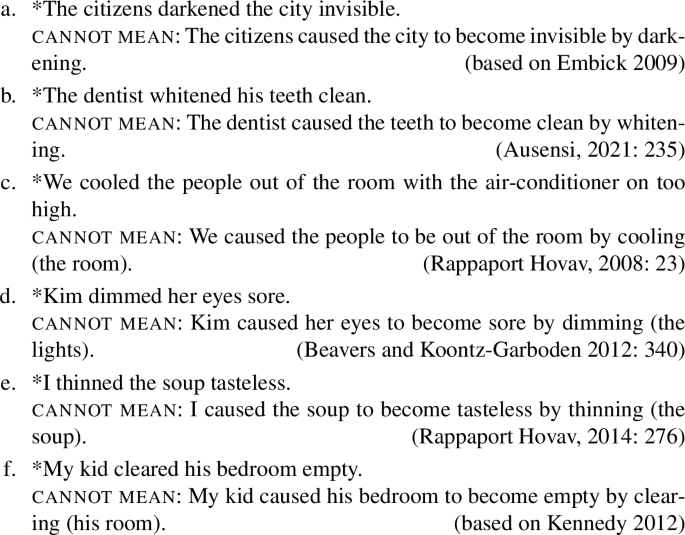

We now return to resultative constructions and how we account for the distribution of result roots in them. Following Kratzer (2005), we take resultative constructions to involve vcause, which introduces a causing relation between an event and a state, but with the possible presence of a root modifying vP, in addition to the result component acting as complement to v. This is in contrast to the simple transitive variant of a verb formed from a property concept root √open as in (22), where the surface verb is produced possibly by the root incorporating into the little v head (e.g., Hale and Keyser 2002). Because of the semantic type of a property concept root and the semantics of vcause, we straightforwardly predict, as do other Ontological Approaches like Rappaport Hovav and Levin’s (1998, 2010), that property concept roots cannot appear in resultative structures where another property concept root or a stative constituent is in the complement of vcause position. This is illustrated in the following example; here, the first (stative) argument of vcause is supplied by the PP the door into the garden and hence the property concept root cannot be vcause’s complement. At the same time, there is no way for the property concept root to serve as a modifier of the event structure; the entire vP is a property of events represented with the event variable e, whereas a property concept root denotes a property of states. Since these are two distinct types, there is no compositional rule that allows the property concept root to modify the overall event.

-

(30)

*Kim opened the door into the garden.Footnote 11

intended: Kim caused the door to go into the garden by opening.

This incompatibility is observed across a large number of roots identified as property concept roots; in addition to the (b) examples in (7–9), the additional examples below attested in the literature involving other verbs derived from property concept roots similarly confirm this prediction.Footnote 12 Property concept roots cannot appear in resultatives as modifiers of the event structure template, with the intended reading being that the result state introduced by the result phrase is brought about by an event introduced by the property concept root.

-

(31)

Note again that the intended interpretations are, in fact, highly plausible, real-world events and not wildly beyond the realm of imagination. That the resultative constructions in question are still judged unacceptable therefore provides evidence against a Free Distribution Approach to the distribution of property concept roots and instead confirm an Ontological Approach where the semantic type of roots determines their relevant syntactic position as we propose here.

We may now turn to the question of how change-of-state roots are integrated into resultative event structures as attested in the naturally occurring data we present. The basic insight, following the logic of our discussion so far, is that as eventive roots, change-of-state roots should naturally be able to occur as modifiers within an eventive event structure even if they intuitively entail a result state, contra the distribution of roots predicted by Manner/Result Complementarity (Rappaport Hovav and Levin 1998, 2010). Importantly, we do not deny that change-of-state roots possess result entailments. As seen in our denotation for √break, it does in fact entail the existence of a result state. The crucial property is that it denotes a relation between an individual and an event of change into a state of brokenness. Hence, while the root entails result, its status as a function from individuals to a property of events allows it to be integrated as modifier of an eventive event structure, correctly predicting its ability to appear in resultative constructions in which there is a separate result phrase acting as complement of vcause. We illustrate with a full syntactic and semantic derivation below; here, the root √break combines with vcause after it has taken its first argument (the constituent labeled v).Footnote 13 The change-of-state root and v are inputs to the compositional rule of Event Identification (Kratzer 1996); this rule combines a function of type <e,<v,t>> (here the type of √break) and another function of type <v,t> (here the type of v), producing a function from individuals to events where the denotations of √break and v are logically conjoined. In a compositional semantic sense, it is a modifier of the event structure as we have been proposing so far.Footnote 14

-

(32)

Notice now that the external argument has yet to be introduced. We follow Kratzer (1996) in assuming that external arguments are introduced by the functional head Voice, also via Event Identification. However, the vP contains an unsaturated individual argument and is of semantic type <e,<v,t>>. This is the wrong semantic type for Event Identification, which combines a function of type <e,<v,t>> (here the semantic type of Voice) and another constituent of type <v,t>, which is the semantic type of Voice’s sister. As a way of getting around this type mismatch, we may follow Alexiadou et al. (2014) in assuming that an operation of Existential Closure may apply at the vP level to produce a constituent that is of the right semantic type to serve as input to Event Identification. Putting everything together, we arrive at the following syntactic structure with the corresponding semantic interpretation.Footnote 15

-

(33)

A few aspects of our analysis are worth highlighting here. First, note that the semantic composition in (33) always entails that there is a state provided by the change-of-state root, in addition to the second result state denoted by the AP complement of vcause. Second, note that the object acting as the holder of the state introduced by the change-of-state root is existentially quantified, i.e., there exists an x such that x became broken. This is regardless of whether the surface object is selected or unselected. In the case above, the surface object is unselected, since it is not the corpse that comes to be broken; rather, something else must have broken in order for the corpse to break loose, here most naturally interpreted as the deck. Finally, note that the same event variable is predicated of become and cause; this means that the event of change leading to a state of brokenness contributed by the root is the same event that causes the result state contributed by the separate result constituent. These aspects are highlighted below for our analysis in (33). As we argue in the following section, this analysis accounts for the interpretations of the naturally occurring examples presented in (10–15), while ruling out examples judged as unacceptable in the literature (e.g., break one’s hands bloody).

-

(34)

Before moving on, we emphasize that our discussion so far bears only on whether change-of-state roots entail result in Rappaport Hovav and Levin’s (1998, 2010) sense. We claim they do, by virtue of introducing an event of change leading to a result. As noted by Rappaport Hovav (2017), even if these roots appear in modifier positions in a resultative event structure, they are still result roots by virtue of entailing scalar change, rather than manner roots entailing non-scalar change, as in Rappaport Hovav and Levin’s (1998) manner versus result classification. In break the corpse loose from the deck, for example, there is simply an event of something becoming broken, which then causes the corpse to become loose from the deck. Nothing specifies how the event of becoming broken was brought about; this could have been accomplished by kicking, using an instrument etc. This is the guiding motivation in our analysis, where we propose change-of-state roots are modifiers of the event structure, rather than claiming they are manner modifiers that specify the manner in which an event is carried out (e.g., Harley 2005). In other words, we do not claim change-of-state roots necessarily have manner entailments by virtue of appearing as modifiers in an event structure, as Rappaport Hovav and Levin (2010) originally proposed. Beavers and Koontz-Garboden (2012, 2020), on the other hand, show extensively that other roots entailing change-of-state, such as those forming verbs of killing (e.g., drown), verbs of throwing (e.g., toss), and verbs of cooking (e.g., poach), do pass a range of diagnostics targeting manner entailments, suggesting they are true mixed manner-result roots. In the absence of a formal characterization of manner entailments, we will continue to remain agnostic on whether entailing change-of-state and appearing as modifiers of an event structure necessarily correlate with a root having manner entailments, focusing instead on how change-of-state roots compose in an event structure.

3.3 Predicted interpretations

Recall now the main interpretive patterns we noted for the naturally occurring examples in (10–15). The first class of examples involves an unselected object, which holds the result state introduced by the AP or PP, but not the state entailed by the change-of-state root. A subset of this class of examples is repeated below.

-

(35)

As noted above, the argument of the change-of-state root which comes to hold the state it entails is existentially quantified. This therefore does not require that the object holding this state corefer with any other DP object expressed within the resultative event structure, even if it can. As a result, we straightforwardly predict the availability of unselected objects in (35), contra Rappaport Hovav and Levin, who predict that these should be ungrammatical, as they demonstrated with (16). Nonetheless, there is an entailment that some object holds the result state named by the change-of-state root. Thus, in (35b), it is the deck introduced within the result AP that is interpreted as being broken, and in (35c), it is some portion of the ice that melted to create a hole. This is the general shape of many examples in (10)–(15): a DP argument introduced within the second result constituent (whether AP or PP) is interpreted as coming to hold the state entailed by the change-of-state root. On the other hand, even if cases like (35a) do not provide such a DP argument (surface him does not come to be torn), it is nonetheless entailed that some entity becomes torn in order for the surface object to become free. As shown below in (36), building on naturally occurring (35a), it is infelicitous to deny that there is an object torn in order to free someone, thus confirming that the existence of a state of being torn is an entailment. Similar observations have also been made by Goldberg (2001) and Rappaport Hovav (2017) in (37).

-

(36)

-

(37)

We may now return to Rappaport Hovav and Levin’s examples, focusing here on examples like (16) which we repeat below, since the surface object may be interpreted as both selected and unselected. What might be the source of the contrast between their examples and the naturally occurring examples we provide?

-

(38)

We argue that the deviance of this sentence is a matter of pragmatics, but crucially one guided by the compositional semantics provided for cases like (33). Since the sentence entails the existence of an object that comes to be broken, the situation described by the resultative construction must provide such an object. In addition, note that in the semantics in (33), the result state described by the result state constituent is caused by the event of becoming broken. Finally, the two result states, the first contributed by the root and the second contributed by a distinct result phrase, must be in a causal chain initiated by a single agent. The resultative construction must therefore describe situations in which the action of the agent leads to something becoming broken, which in turn results in some other state described by an AP or PP.

With this backdrop in mind, consider now (38). We predict there are at least two possible interpretations. In the first, we might think of his hands as a selected object, in that some person’s hands come to be broken. If so, (38) is most likely ruled out as a matter of conceptual knowledge; breaking of hands typically involves bones being broken, which does not necessarily lead to them being bloody. To the extent that this selected object interpretation is available, a possible context would be that the event of breaking one’s hands caused weakness in a person’s grip, and as a result of the weakness in their hands, they may have accidentally cut themselves while attempting to grip a sharp object. However, lexical causatives like kill, which are frequently analyzed on par with resultative constructions with a property concept root √dead incorporating into vcause (Harley 2012), are known to be incompatible with contexts in which an intermediate entity affected by the agent comes to cause the causee to hold some result state, i.e., they must entail direct causation (see also Levin and Rappaport Hovav 1995; Bittner 1999; Rappaport Hovav and Levin 2001; Kratzer 2005; Levin 2020; amongst many others). In such cases, a periphrastic causative is required, as (39) shows.

-

(39)

A gunsmith faultily repairs the gun that a sheriff brings him for inspection. The next day, the sheriff’s gun jams and he is killed when he tries to defend his town from incoming bandits.

Given this fact about lexical causatives, which involve vcause just like resultative constructions, even if the context described above is a plausible scenario where the breaking of one’s hands can lead to them being bloody, it is a case of indirect causation, and thus cannot be described by (38) due to the direct causation requirement imposed by vcause. This is in fact the precise intuition expressed by our compositional semantics; the agent’s action leads to something becoming broken and this change event in turn leads to the hands becoming bloody. No other entity should intervene as an intermediate causer that causes the bloody state in (38), since it is the change event itself that causes this resulting state.

The same reasoning also rules out the unselected object reading in which his hands were not broken and something else broke, which somehow at the same time also caused a person’s hands to be bloody. The only available conceptual situation in which this is plausible is if the broken object had in some way hurt the person and caused the spilling of blood. For example, the agent could have broken a vase, with the sharp, broken pieces of the vase going on to cut their hands, causing them to become bloody. If so, this is again an instance of an intermediate entity causing the result state of being bloody, a scenario ruled out by the requirement of direct causation. Note as well that in attested examples like broke the corpse loose from the deck, the deck is indeed interpreted as being broken, but it does not affect the corpse in a causal fashion such that the corpse became free. Rather, it is simply the change in the deck from being unbroken to broken that frees the corpse. Again, this is an interpretation that is enforced by the compositional semantics that we proposed, specifically that the change event directly causes the state of the corpse being loose from the deck. The reader may go on to verify that this is indeed the case with the attested examples in (10–15) involving surface unselected direct objects, but with a DP contained inside an AP or PP that holds the result state entailed by the change-of-state root.

We now turn to the second attested interpretation when change-of-state roots appear in resultative constructions, seen most prominently in our naturally occurring data in (12a) repeated below. As we noted, the natural interpretation here is that one of the letters came to be torn, while a piece of the letter came to be separated from it as a result.

-

(40)

In fact, such interpretive patterns have been noted before in prior literature. For example, Levin and Rappaport Hovav (1995) discuss the following example involving crack.

-

(41)

Kim cracked the egg into the bowl.

As has been noted by many, this pattern is unexpected, since it has been observed that two distinct result states (scalar changes along distinct dimensions) cannot be predicated of a single object (Simpson 1983; Jackendoff 1990; Goldberg 1991; Levin and Rappaport Hovav 1995; Rappaport Hovav 2014; Beavers and Koontz-Garboden 2017). Here, it is unexpected that the egg can become both cracked and inside a bowl. Goldberg (1991: 368), for example, formulates this explicitly as a semantic constraint dubbed the Unique Path Constraint.

-

(42)

Unique Path Constraint: if an argument X refers to a physical object, then more than one distinct path [scale] cannot be predicated of X within a single clause.

Nonetheless, Levin and Rappaport Hovav (1995) note that (41) is most naturally understood as meaning that distinct parts of the egg come to hold distinct result states: the eggshell becomes cracked while the contents of the egg end up in the bowl as a result of the cracking of the eggshells. This is therefore not a violation of the Unique Path Constraint (see also Beavers and Koontz-Garboden 2017). For our purposes, we argue that this interpretive pattern falls out directly from the compositional semantics we provide for change-of-state roots when they are modifiers of an event structure. Since the holder argument of the state that they entail is existentially quantified, the option of interpreting this existentially quantified entity as coreferential with the surface object is possible, leading to a selected object interpretation. Nonetheless, if two distinct result states that are conceptually unrelated cannot be predicated of the same object under the Unique Path Constraint, then one naturally must make use of other strategies to avoid predicating two distinct result states of the same object. One salient and obvious strategy is the part-whole relationship, where distinct parts of the same object come to hold different result states within a single clause. Importantly, the semantic representation retains the holder argument of the result state entailed by the change-of-state root. It is this fact that allows for the possibility of a selected object interpretation, correspondingly forcing the use of interpretive strategies like part-whole relationships in certain contexts. Further examples of such an interpretive pattern are illustrated below.

-

(43)

One caveat is in order here. As noted previously, Rappaport Hovav and Levin (1998, 2010) propose Manner/Result Complementarity as a hard grammatical constraint, tightly regulating the distribution of manner and result roots in particular sorts of event structures. Therefore, what they classify as result roots should never appear in resultative constructions as modifiers of an event structure, a problematic empirical claim as we have demonstrated here. In contrast, we analyze some result roots as eventive, specifically change-of-state roots that denote events of change and therefore, are predicted to appear in resultative event structures as modifiers. Nevertheless, we observe that not all resultative constructions are judged equally acceptable. We suggest that this is due to both the semantic constraint of direct causation imposed by how the change-of-state root is integrated into a resultative event structure template, as well as speakers’ differing knowledge about the normal courses of events in the world, as also proposed by Free Distribution Approaches (e.g., Borer 2005; Acedo-Matellán and Mateu 2014). Returning, for example, to break his hands bloody under a selected object interpretation, we noted that this is often judged unacceptable because of an interaction between the compositional semantics and the real-world, prototypical understanding of hand-breaking events. It is unlikely that a hand-breaking event alone will cause any spilling of blood given what we know of how such events unfold; most likely, it is another object that ends up causing the spilling of blood in a sequence of events resulting from hand-breaking. This is explicitly ruled out by the compositional semantics we provide, which requires direct causation. However, we also predict that as contexts get more specific, acceptability of such constructions might improve, subject to the above semantic constraints. One such possible context is outlined below, assuming a selected object interpretation and that the breaking of one’s hands here really involves breaking of the bones in one’s hands while another portion of the hand becomes bloody, essentially a part-whole interpretive strategy. Here, one might suggest that this is a more plausible, real-world scenario where a hand-breaking event can lead to uncontrolled bleeding.

-

(44)

context: John broke his hands. It was such a severe fracture that the sharp edges of the broken bones in his hand pierced through his flesh when they broke and he bled profusely.

?? John broke his hands bloody.

To our ears, while this does not sound completely acceptable, it does seem to contrast with the context of another hand-external, broken object cutting through one’s hands and causing uncontrolled bleeding (i.e., an unselected object interpretation). Nevertheless, as an anonymous reviewer points out, judgment of the acceptability of this sentence varies rather widely. However, we believe this is exactly what we predict to hold. A part-whole interpretive strategy can help to avoid a violation of the Unique Path Constraint in that two distinct scalar properties are predicated of two distinct parts of an object, possibly explaining why it sounds better than having a hand-external object cutting through the broken hand, which violates the direct causation requirement. Yet, (44) still does not satisfy the requirement that the event of becoming broken directly causes the bloodiness. The breaking of one’s hands alone is not sufficient to immediately cause bleeding; rather, the part-whole interpretive strategy imposes an interpretation where the broken bones must, in some fashion, pierce through some flesh in order to cause bleeding. In other words, it is not the change event itself that leads to the bleeding, but some other entity involved in an intermediate event that causes the state of bloodiness. This, of course, is ruled out by our proposed compositional semantics, on a par with the context of having a hand-external object cutting through the hand. On the other hand, the context in (44), imposed by a part-whole interpretive strategy, is in fact a plausible (albeit fairly uncommon) real-world hand-breaking event. It seems plausible that the part-whole interpretive strategy interacting with the direct causation requirement and real-world, conceptual knowledge about hand-breaking events is exactly what leads to these widely-differing judgments, as some speakers might prioritize satisfying the Unique Path Constraint at the expense of somewhat relaxing the direct causation requirement, while other speakers prefer the reverse, so long as the real-world event the resultative construction is being used to describe is actually conceptually possible. As further illustration, contrast (44) under the selected object interpretation with the naturally occurring (40) and Levin and Rappaport Hovav’s (41). These are notable in also utilizing the part-whole interpretive strategy to avoid violating the Unique Path Constraint, but to our ears, these are perfectly acceptable as compared to (44). This contrast, we believe, lies in the fact that these two examples do in fact satisfy the direct causation requirement. In virtue of getting torn, a smaller piece of the paper naturally becomes free of the larger piece and in virtue of being cracked, the contents of the egg can naturally flow into the bowl; no other entity need intervene to cause these respective result states. Therefore, the part-whole interpretive strategy nonetheless needs to impose an interpretation consistent with direct causation of the result state by the change event encoded in the change-of-state root, as well as describe plausible real-world situations compatible with the change event. Otherwise, we expect less than perfect acceptability, which is what we see here.

In contrast, we saw as well that not all result roots are going to be flexible and subject to both semantic and pragmatic considerations in resultative constructions, as observed with change-of-state roots above, contra Free Distribution Approaches (e.g., Borer 2003, 2005; Acedo-Matellán and Mateu 2014). In particular, property concept roots forming verbs like open, darken, whiten, cool, thin, and clear etc., in virtue of being underlyingly stative, will always be complements of eventive v heads and for this reason, are not predicted to appear in resultative constructions as event structure modifiers at all, regardless of whether highly specified contexts are provided to guide possible interpretations. Even if the constructed context below is not difficult to imagine and perfectly possible, the following sentence with open appearing as an event structure modifier still contrasts sharply with examples like (44) with a change-of-state root in event structure modifier position. In other words, building a highly articulated context as in examples like (44) could potentially improve the judgment of resultative constructions containing a change-of-state root, whereas constructing a plausible context in (45) nonetheless does not seem to improve the judgment of resultative constructions containing a property concept root in event structure modifier position. This observation means that Free Distribution Approaches that appeal to pragmatic constraints and the plausibility of real-world events would face difficulties in trying to rule out cases like (45).

-

(45)

context: There was a door leading to the garden. The hinges were really loose and the door was on the verge of falling off them. John wanted to go out to his garden to tend to his plants. He opened the door with too much force, however, and the door broke off its hinges and fell onto his garden lawn.

*John opened the door into the garden.Footnote 16

To our minds, this is true of all the other examples attested in the literature; we reproduce the ones in our earlier discussion. While it is in principle possible to construct highly articulated contexts in which one might think these would be felicitous, they are nonetheless judged unacceptable in the literature as with (45), as the reader may confirm.

-

(46)

We close this section by discussing examples involving property concept roots which, at first blush, appear to pose a challenge to the claim that the roots of this class cannot function as event structure modifiers. For instance, the following naturally occurring examples appear to resemble the unacceptable examples in (46) above.

-

(47)

We suggest, following Ausensi (2021), that in these examples, the result phrases denote result states that are a further specification of the state encoded by the roots, i.e., they do not introduce distinct result states as in examples like With a few slices of her claws, she tore him free (Rappaport Hovav and Levin 2010; Beavers 2011; Mateu 2012). For instance, the phrase ajar is a specification of the degree of openness that holds of the door; it does not denote a scalar change in a different dimension, which would be ruled out by the Unique Path Constraint. As Beavers (2011) discusses in detail, similar cases include verbs like cool or lengthen, which only take result phrases that are a further specification of the scale of change denoted by the verbs, e.g., cool the soup to \(10~^{\circ}\text{C}\) and lengthen the jeans 5 centimeters respectively. Other examples of this type, which are possible also with change-of-state roots, are provided below (see further Rappaport Hovav and Levin 2010; Beavers 2011; Rappaport Hovav 2014).

-

(48)

These examples will receive an analysis where the property concept root is in the complement position and the apparent result phrases are modifiers of the result state that the verbal root encodes (Mateu 2012; Acedo-Matellán et al. to appear). We refer the reader to these works for detailed discussion of these apparent counterexamples. A detailed semantic analysis of how the apparent result phrases come to further specify the state that the property concept root denotes will be left for future work (though see Beavers 2011 for discussion of the formal tools that might be required to implement this).

-

(49)

Open the door ajar.

4 Previous analyses

We turn now to a brief outline of possible alternative accounts for the empirical observations we presented above, specifically regarding the lexical semantics of change-of-state roots and how they are integrated into event structures. The overall picture is that these approaches, while equally adept at accounting for the appearance of these roots in resultative constructions, face particular theoretical and empirical challenges that our approach does not.

4.1 Change-of-state roots as predicates of states: Beavers and Koontz-Garboden (2020)

As Beavers and Koontz-Garboden (2020) show in detail, change-of-state roots entail change in addition to a result state, which is the basic insight we have adopted so far. There is, however, an important implementational difference; for them, result roots are underlyingly stative rather than eventive, as shown with the root √break.

-

(50)

〚√break〛: λx.λs.broken(s,x) ∧ ∃e[become(e,s)]

This straightforwardly predicts that presupposition triggers like again will not produce a purely stative restitutive presupposition, as the root itself entails the existence of an event that causes the state. As Beavers and Koontz-Garboden show, this is indeed borne out as previously detailed in (25). From the perspective of sub-lexical modifiers like again, it seems their particular implementation is indistinguishable from ours.

However, as we noted before, durative for-phrases can tease apart the two analyses. The relevant observation is the lack of Dowty’s (1979) internal readings with verbs formed from change-of-state roots, in contrast with the ambiguity between the eventive durative reading and the internal reading with verbs formed from property concept roots. We repeat the relevant contrasts below.

-

(51)

Susan opened the door for two hours.

-

(52)

Susan broke the vase for 5 minutes.

Under our analysis where change-of-state roots are eventive and entail the existence of a result state, this is straightforwardly accounted for: only an event variable is available for modification by both again and for-phrases with change-of-state roots, and therefore only the repetitive and durative readings of these modifiers are available. On the other hand, if the change-of-state root is stative as in Beavers and Koontz-Garboden (2020), attaching a for-phrase to the stative constituent containing the root predicts a reading where the state’s duration lasted some amount of time, independent of the duration of the event of change, an unwelcome result.

A second issue concerns the naturally occurring resultative constructions we consider here. Given Beavers and Koontz-Garboden’s stative analysis of change-of-state roots, such roots must serve as complements of eventive v heads encoding semantic operators like cause and become, as Beavers and Koontz-Garboden themselves propose. Against this backdrop, consider again the examples from before; the following is a use of break with two distinct result states and an unselected surface object.

-

(53)

How might Beavers and Koontz-Garboden account for the semantics of such constructions? They do not consider such constructions, so we may infer based on the range of compositional rules available to us. For starters, the denotations of the root and AP on their approach are given below.

-

(54)

-

a.

〚√break〛: λx.λs.broken(x,s) ∧ ∃e[become(e,s)]

-

b.

〚the corpse loose from the deck〛: λs.loose-from(c,d,s)

-

a.

Given the assumption that √break is the complement of v, according to Beavers and Koontz-Garboden’s approach, we might then suggest that the corpse loose from the deck is modifying √break, much like the structure for open the door ajar in (49). This is because there is no other way in which the stative AP constituent can be integrated into a resultative event structure, as with property concept roots in this context illustrated in (30). If so, one available compositional rule for combining the root and the distinct result state is Event Identification, combining a constituent of type <e,<s,t>> (√break) with another of type <s,t> (the corpse loose from the deck) (Kratzer 1996).

-

(55)

〚√break the corpse loose from the deck〛:

λx.λs.broken(x,s) ∧ ∃e[become(e,s)] ∧ loose-from(c,d,s)

Because of Event Identification, the same state variable is predicated of √break and the corpse loose from the deck, and the two state descriptions are logically conjoined. This results in the state s being both a state of brokenness and a state of the corpse being loose from the deck. However, this does not accord with the intuition that a state of being broken and a state of being loose from the deck should be two distinct states with unrelated properties. In contrast, our analysis for examples like (33) delivers precisely on this intuition; the two state variables in (33) are distinct s and s’, contributed by the root and the result phrase separately.

Even granting that this above concern is not an issue, and the single state variable can indeed have two differing and unrelated descriptions, an additional issue arises here. Once the individual argument in (55) is saturated, however this is achieved (e.g., Existential Closure since there is no other surface DP), there will be two holders of the differing state descriptions of a single state variable. That is, the corpse holds the state of being loose from the deck and possibly something else holds the state of being broken (e.g., here the deck), though these are in fact one and the same state since they are predicated of the same state variable. This, however, is impossible; in fact, this has been noted by Carlson (1984) and Landman (2000) as a constraint on thematic roles, namely, that any single eventuality can have only one instance of any particular thematic role. Landman (2000), for example, formulates this explicitly as a Unique Role Requirement. If the two state descriptions here combine via Event Identification, the thematic role one might label Holder of the state s is going to be specified twice, violating the Unique Role Requirement.

-

(56)

Unique Role Requirement: If a thematic role is specified for an event, it is uniquely specified.

It is unclear to us if there is any way one might prevent Beavers and Koontz-Garboden’s analysis from running into these issues, given the underlying assumption that change-of-state roots denote properties of states, and the available compositional rule for combining it with another result phrase also denoting a property of states in a resultative event structure is Event Identification. We thus conclude that, in light of the empirical and theoretical issues we consider here, an analysis along the lines of what we propose is more desirable.

4.2 Change-of-state roots as predicates of events selecting a state complement: Embick (2009)

Embick (2009) proposes that change-of-state roots are eventive and always function as event modifiers, much like we do. Crucially, rather than entailing a change-of-state semantically, these roots syntactically select what Embick calls a “proxy” stative complement (ST). This is motivated by the Bifurcation Thesis for Roots, defined as follows (see also Arad 2003; Borer 2005; Dunbar and Wellwood 2016):

-

(57)

On this view, change-of-state roots thus cannot contain semantic entailments of change-of-state, which are introduced strictly by the structural context into which they are integrated. They are therefore always integrated into a structure containing an unspecified state.

-

(58)

√break selecting for a proxy state

Embick suggests that if the ST proxy is not given content by other elements, as in (58), it is named by the change-of-state root adjoined to v. In (58), ST is interpreted as the state that comes about after a breaking event is over, i.e., broken. On the other hand, ST can be provided with content when it is named by another root denoting a state, e.g., √open.

-

(59)

Break the package open.

While this may simply look like an implementational difference from our proposal, in which change-of-state is encoded syntactically rather than semantically, there are in fact both conceptual and empirical consequences. Conceptually, it is unclear how to implement the proposal that the change-of-state root names the proxy state from a compositional semantic view. It seems to us that there is no compositional rule that would allow a simple predicate of events to also compositionally provide a description for a state variable in its sister constituent, short of the root entailing this state itself, which is effectively what we propose.Footnote 17

Empirically, we return to a pattern of entailment that we discussed previously, namely that even in resultative constructions where a distinct result state is introduced, the result state entailed by the change-of-state root remains an entailment. As we noted, denying that this state holds is infelicitous for verbs formed from change-of-state roots like √tear (Goldberg 1991; Rappaport Hovav 2017).

-

(60)

Consider now what Embick’s analysis would predict here. Since there is a second property concept root √free, this root will provide ST with a state description. Given that √tear is a simple property of events, the resulting compositional semantics should entail only that there was a result state of being free and not being torn. In other words, there should be no expectation that any object became torn as a result of the tearing event, only that an object became free. One might then say that an object being torn is a matter of inference based on conceptual knowledge. Nonetheless, as the denial test above shows, such a state must in fact be entailed and not simply defeasibly inferred. Under Embick’s analysis, there is simply no way to enforce this entailment pattern short of analyzing the change-of-state root as entailing a result state in itself, which is effectively identical to what we propose here. We thus conclude that change-of-state roots are underlyingly eventive and also entail a result state that they themselves name, rather than being embedded in a syntactic structure that introduces one, contra Embick’s (2009) Bifurcation Thesis for Roots (see Beavers and Koontz-Garboden 2020 for more detailed discussion against it).

5 Conclusion

We began this paper with the question of what constrains root distribution in event structure templates. Two different approaches to this question are found in the literature: Ontological Approaches that suggest the semantics of roots, specifically entailments of manner or result in a Manner/Result Complementarity, determine the kinds of event structures they appear in, and Free Distribution Approaches, where root distribution is unconstrained by semantics since roots do not contain grammatically relevant semantic information. We examined resultative constructions in which distinct roots are used for the manner and result components in an event structure and their interactions with roots classified as result roots by Rappaport Hovav and Levin (1998, 2010). The basic empirical insight is that a result root’s status as a property concept root or a change-of-state root predicts its position in an event structure template: property concept roots appear strictly as complements of v, while change-of-state roots appear as modifiers in the event structure in resultatives. We presented naturally occurring examples of change-of-state roots appearing as modifiers of a resultative event structure, since the possibility of these cases is debated in the literature, with acceptability judgments often differing from author to author. These observations counterexemplify both an Ontological Approach that makes reference to manner versus result entailments and a Free Distribution Approach where all roots should be able to freely appear in either position.

To account for these observations, we proposed a compositional semantics for these two root classes and demonstrated how they are integrated into a syntactic event structure template. Specifically, property concept roots denote relations between individuals and states, and thus are always integrated as complements of eventive v heads. As such, they never appear in resultative constructions specifying the result component, because this position is filled by an overt result phrase. Neither can they appear in these constructions in an event modifier position, since they are not of the correct semantic type to be integrated there. On the other hand, change-of-state roots denote relations between individuals and events that entail change-of-state, and consequently appear as modifiers of resultative event structures. This possibility is due to their semantic type being compatible with the type of the vP they modify. In addition, we noted that while pragmatic and conceptual knowledge often affect the acceptability judgments of change-of-state roots appearing in modifier positions in resultative event structures, the interpretations are not completely unconstrained. The proposed semantic representations of such constructions can guide and predict when they are likely to be more acceptable and vice versa due to constraints like the direct causation requirement. Put another way, our proposed semantics restricts the conceptual and contextual space in which we expect to find speaker variation in acceptability of change-of-state roots used in resultative constructions as modifiers. So long as the resultative construction containing a change-of-state root satisfies interpretive constraints imposed by the compositional semantics, we predict the possibility of it being judged acceptable and any disagreement can be attributed to speakers’ knowledge and experience with the type of real-world event that the resultative construction is meant to describe.

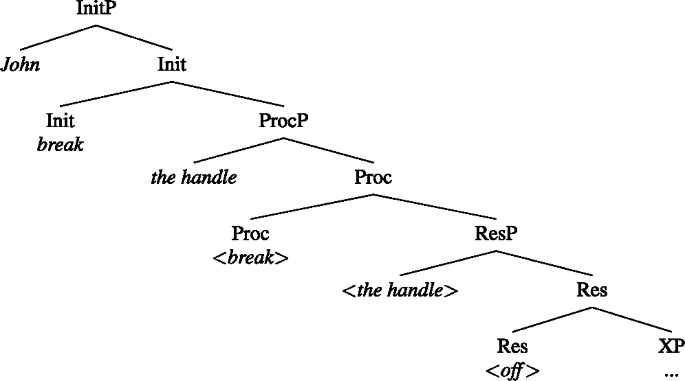

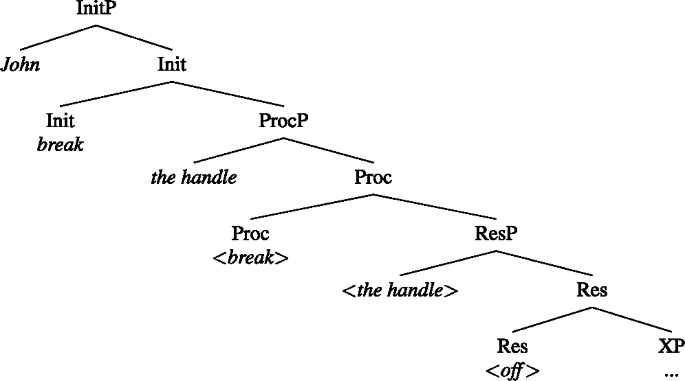

By way of closing, we might reflect on how our approach fits into the overall question of how roots are distributed in event structure templates as well as other approaches that dispense with some of the key assumptions we adopted here. We defended in broad terms a view where Rappaport Hovav and Levin’s (1998, 2010) Manner/Result Complementarity does not map directly to root distribution in event structure templates, even if it is a useful characterization of the semantic entailments that roots can have, and also a view that argues against Embick’s (2009) Bifurcation Thesis for Roots and related constraints on possible verb meanings. For us, it is the type-theoretic properties of roots that arise from certain lexical-semantic entailments, such as entailments of change, that determine their distribution and consequently, their ability to appear in resultative constructions. Alternatively, one might recast this basic intuition in different terms. One such approach is that of Ramchand (2008), who proposes a universal, “first-phase” event-building clausal spine consisting of the semantically well-defined functional heads Init(iation), Proc(ess), and Res(ult). These provide the relevant semantics of causation, change, and result and are in a strict selectional relation. Importantly, the approach dispenses with a key assumption implicit in the approaches we have discussed here, namely, the assumption that a root associates with only one position in a syntactic event structure template. A simple transitive sentence with break might therefore be analyzed as below, with the root of break either being first merged in Res (indicated by angled brackets) and then remerged in the higher Init and Proc heads, or it “spans” a number of heads in approaches like Nanosyntax (e.g., Starke 2009, amongst others) instead of spelling out a single head. In other words, break is lexically specified as [Init,Proc,Res] and associates with all three heads, while the surface object associates with two specifier positions as both the resultee holding a result state and also the undergoer, the object affected by a process.

-

(61)

Katherine broke the stick.

This approach can be fruitfully extended to the cases we consider here by assuming that a separate element can be associated with Res. In such cases, break, specified as [Init, Proc,Res], can underassociate, with the constraints on underassociation being that the feature that a lexical item is specified for but does not associate with must itself be independently identified by another lexical item and that the two lexical items’ encyclopedic content must be unified (Ramchand 2008: 98). This is demonstrated with examples of break occurring with particles that independently associate with Res; break therefore underassociates with Res and only associates with Init and Proc in (62).

-

(62)

John broke the handle off.

While Ramchand (2008) considers instances of break-type verbs occurring with a particle that associates with Res and not the kinds of cases we consider here, we assume that a similar analysis will be given to examples like break the corpse loose from the deck, with loose identifying Res and the PP being rhematic material to Res identifying a location, indicated by XP in the structure in (62).Footnote 18