Abstract

This paper investigates the morphosyntax of resumption in Igbo (Benue-Congo). The first part addresses the syntax and argues that Igbo has two types of resumptive pronouns (RPs): (i) RPs that terminate base-generation Ā-dependencies, and (ii) RPs at the bottom of Ā-movement dependencies. While similar splits have been claimed to exist in a few other languages, established with a limited data set, Igbo provides pervasive evidence for the co-existence of both types within the same language: type-(ii) RPs occur in all Ā-movement dependencies, and there is comprehensive evidence from a variety of movement tests, including also cyclicity effects, parasitic gap licensing, and language-specific diagnostics. We pursue a spell-out approach to type-(ii) RPs à la Pesetsky (1998) and Landau (2006), and discuss potential reasons behind their restricted distribution: type-(ii) RPs only surface in PPs, DPs, and &Ps, which are thus not (absolute) islands in Igbo. The second part of the paper deals with the morphological side of resumption, viz., with phi- and (alleged) case mismatches between the RP and its antecedent. The phi-mismatch provides further evidence for two types of RPs in Igbo. Moreover, it is more complex than the mismatches reported so far in the literature since the loss of phi-information depends on the type of antecedent (pro/noun, coordination). This pattern poses a challenge for previous accounts of phi-mismatches with movement-derived RPs that are based on static deletion domains. We propose that the cross-linguistic variation in phi-mismatches can be captured in a partial copy deletion approach along the lines of van Urk (2018) if the amount of structure that is deleted is defined dynamically. This further supports the relevance of dynamic domains in morphosyntax, in particular in postsyntactic operations, as previously identified in other areas, e.g., in Moskal’s (2015b) work on contextual allomorphy. Finally, we show that the “case” mismatch is a consequence of the (supra)segmental nature of the relevant exponent and the relative timing of the operations involved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper reports on a study of the syntax and morphology of resumption in Ā-dependencies in Igbo, a Benue-Congo language spoken in Nigeria. In the first part, we consider the distribution of RPs and the nature of the syntactic dependencies that RPs occur in. For this purpose, we contrast topicalization with focus fronting. Both constructions can host RPs, but their status is not the same: while the RPs found with topicalization terminate a base-generation Ā-dependency, those that occur under focus fronting surface at the bottom of an Ā-movement dependency. We thus argue that Igbo has two different types of RPs. While similar RP-splits have been reported for a few other languages before, the evidence available in the literature usually comes from RPs in relative clauses (RCs), and is mainly based on island-sensitivity and/or (sometimes very subtle) reconstruction effects. Igbo, on the other hand, offers comprehensive evidence: first, RPs that terminate movement chains occur in all Ā-movement dependencies (focus/wh-fronting, relativization). Second, the empirical evidence additionally includes cyclicity effects, parasitic gap licensing, and language-specific diagnostics. Igbo is thus the first language for which we have evidence from all major movement tests for the co-existence of two RP-types.

We argue that RPs in movement dependencies in Igbo are best captured in a spell-out approach to resumption, where RPs realize subparts of lower copies. Following the optimality-theoretic analyses by Pesetsky (1998) and Landau (2006), we assume that RPs pronounce the D-head of a lower copy (see Postal 1969; Elbourne 2001) that is affected by partial rather than by (default) full deletion (which results in a gap). Partial deletion is a repair triggered by pronunciation requirements (which we take to be related to prosodic prominence) associated with certain positions. In fact, RPs in movement chains do not freely alternate with gaps in Igbo. Rather, they are required in only a few contexts, i.e., when an element is subextracted from a PP, a DP or an &P. These constituents are thus not (absolute) islands in the language.

The second part of the paper investigates the morphology of resumption in Igbo. The language exhibits both phi- and (what we will provisionally call) case mismatches between the antecedent and its RP—but only in Ā-movement dependencies, not in base-generation dependencies. This provides further evidence for the existence of the two types of RPs argued for in the first part. Moreover, the Igbo phi-mismatch is more complex than previously described patterns because the loss of person and number information depends on the type of antecedent (pronoun vs. lexical noun, coordination). This pattern challenges previous accounts of phi-mismatches in movement-derived resumption, which involve static deletion domains, e.g., van Urk (2018) and work based on his proposal. We propose that the cross-linguistic variation, including the Igbo split pattern, can be captured if the domain for partial deletion is defined dynamically (context-dependent). Differences between the antecedent types are a consequence of (in part independently established) structural differences between them. The pronoun/noun split as well as the use of dynamic domains for postsyntactic operations is reminiscent of Moskal’s (2015b) work on contextual allomorphy. “Case” incongruity arises in all Ā-dependencies when an RP surfaces in a genitive-marked position, while antecedents always occur in their accusative form. We argue that this mismatch falls out from the timing of the operations involved once we (a) recognize that the morphological alternation is not a realization of abstract case, and (b) take into account the tonal nature of the genitive.

The paper is structured as follows: Sect. 2 gives an overview of the basic grammatical properties of Igbo. In Sect. 3 we provide evidence from a number of movement tests for the claim that Igbo has both base-generation dependencies, which terminate in an RP, and Ā-movement dependencies that usually leave gaps. We show in Sect. 4 that there are four contexts which require an RP in Igbo even though the dependency involves Ā-movement. In Sect. 5 we argue for a partial copy deletion approach to RPs in movement dependencies as proposed in Pesetsky (1998) and Landau (2006). Section 6 addresses phi-mismatches; and Sect. 7, “case” mismatches in resumption. Section 8 concludes. The Appendix includes (A) additional movement test data and (B) a discussion of the triggers of movement-related resumption. Unless references are provided, the Igbo data and judgments in this paper come from the native speaker co-author, Mary Amaechi, who speaks the standard variety. The data were cross-checked with three other native speakers. While some of the facts regarding the syntax of focus fronting in Sect. 3 have been observed in the literature cited there, we use our own examples with different lexical items to provide minimal pairs throughout this paper as much as possible.

2 The Igbo language

In this section we briefly summarize the basic grammatical properties of Igbo that will be relevant for our study; see the grammars by Green and Igwe (1963); Carrel (1970); Manfredi (1991); Uwalaka (1997); Mbah (2006); Emenanjo (1978, 2015). The basic word order in a declarative all-new sentence in Igbo is SVO; adjuncts occur in the clause-final position, see (1).Footnote 1

-

(1)

This order can be changed to express information-structural categories such as topic and focus; see Sect. 3. Igbo is a tone language that distinguishes low (à) and high tone (á) as well as a downstep (!á) (Green and Igwe 1963; Goldsmith 1976; Nwachukwu 1995). The downstep is a pitch drop that arises when two high tones associated with separate tone bearing units are adjacent (Clark 1990). Tone in Igbo has not only lexical but also grammatical functions; for example, the difference between a declarative sentence and a yes-no question based on it is expressed by a different tone on the pronominal subject. Igbo has rich verbal morphology that indicates derivation and inflection (e.g., tense, aspect; Uwalaka 1988). Vowels come in [±ATR] pairs; we encode the [–ATR]-variants by a dot subscript. Regarding nominal inflection, the 2sg and 3sg personal pronouns exhibit two forms, which we will provisionally identify as morphological case: the V(owel)-form of these pronouns (í, ó) can only be used as the subject of an (in/di)transitive verb, while the CV-variant (g , yá) has a much wider distribution and must be used, e.g., in (in)direct object function; see (2) (and Manfredi 1991: 233; Déchaine and Manfredi 1998: 76f).

, yá) has a much wider distribution and must be used, e.g., in (in)direct object function; see (2) (and Manfredi 1991: 233; Déchaine and Manfredi 1998: 76f).

-

(2)

Given that the distribution in (2) corresponds to the typical nominative-accusative pattern, we will call the V-forms of the 2sg and 3sg pronouns the NOM(inative) exponent, and the CV-forms the ACC(usative) exponent. This is in line with the terminology used in Emenanjo (2015: 29–30, 304) and (partially) Manfredi (1991: 233).Footnote 2 Other pronouns and all lexical nouns do not distinguish NOM- and ACC-forms, there is only a single exponent that covers both uses, see the pronominal paradigm in (3).Footnote 3 In what follows, we will indicate NOM/ACC glosses only for pronouns, but not for nouns; we will refer to the form of nouns in NOM/ACC-contexts as their base form.

In addition, nouns and pronouns exhibit a form that is referred to as GEN(itive) in the literature. It is used to indicate possession (in the associative construction) and for direct objects in certain aspects; GEN is expressed by a tone change (at least in some environments; see Goldsmith 1976; Clark 1990; Nwachukwu 1995; Manfredi 2018). With monosyllabic pronouns the GEN-form is distinct from both the ACC- and the NOM-form. See (4) for examples with the 3sg pronoun and the proper name Chí (base form): GEN is segmentally identical to ACC/the base form but surfaces with a downstep rather than a high tone. We will discuss “case” in Sect. 7 and argue that the morphological alternations in (3) are in fact the result of allomorphy.

-

(4)

We adopt the clause structure in (5) for a declarative clause with a transitive verb such as 2 (without the adjunct) from Amaechi and Georgi (2019):

-

(5)

Heads precede their complements in Igbo, i.e., the VP (PP, NP) is head-initial. The external argument (DP\(_{ext}\)) is base-generated in Specv. The structurally highest argument moves to SpecT due to the obligatory EPP of T. The finite verb moves cyclically through v and Asp to T. See Déchaine (1993); Amaechi (2020) for justification of these assumptions and further references.Footnote 4

3 Base-generation vs. Ā-movement in Igbo

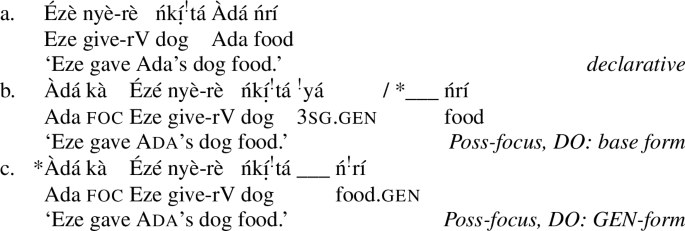

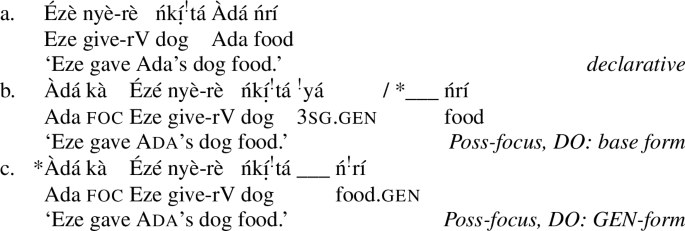

In this section we investigate the formation of Ā-dependencies in Igbo. We will contrast focus fronting (focus ex-situ) and topicalization applied to direct objects (DO); we will comment on other grammatical functions and on other Ā-dependencies later. This section summarizes the results of our previous work on the morphosyntax of focus fronting (including ex-situ wh-questions) in Igbo, see Amaechi and Georgi (2019); the language-specific tests as well as the cyclicity and topicalization data presented here were not included in that work, however.Footnote 5 Consider the declarative sentence in (6a), which is our baseline. New information and contrastive focus in Igbo can be expressed by putting the focus XP in the clause-initial position where it is followed by the focus marker kà, see (6b). In the canonical postverbal position of the DO we find a gap (underlined); using an RP (= 3sg ACC pronoun yá) leads to ungrammaticality. Focused XPs are represented in small caps in the English translations throughout the paper.Footnote 6 A topic XP also occurs in the clause-initial position, but it is not followed by a specific morpheme (there is no topic marker), only by an intonational break. The canonical postverbal DO-position must be filled by an RP (= 3sg ACC-pronoun yá); a gap is impossible, see (6c).

-

(6)

The application of a set of general movement tests as well as of two language-specific movement diagnostics (=LSMDs) to dependencies with a clause-initial focus or topic XP (summarized in Table 1) leads us to conclude that focus fronting is the result of movement, while topicalization involves base-generation of the topic XP at the left edge of the clause: focus fronting is sensitive to islands and to two LSMDs, exhibits reconstruction and tonal cyclicity effects, licenses parasitic gaps (pgs); topicalization has none of these properties.

In what follows, we illustrate these properties. Complex noun phrases (CNPs) are islands in Igbo. (7) shows that focus fronting the DO out of a relative clause is ungrammatical, while topicalizing the DO is fine.Footnote 7 Note that long-distance focus fronting is possible in Igbo (see e.g., (8)[b]); the ungrammaticality of (7b) is thus not simply caused by the crossing of a clause boundary.

-

(7)

Focus fronting reconstructs to the gap position in Igbo. We illustrate this here for Strong Cross-Over (SCO) and idiom interpretation.Footnote 8 In the baseline in (8a), the matrix 3sg subject pronoun cannot be co-referent with any of the proper names in the embedded clause as this would cause a Principle C violation. When the DO of the embedded clause is focused, it still cannot be co-referent with the matrix subject, see (8b). This follows if the fronted XP reconstructs to the gap position. There are, however, no restrictions on co-reference between a topic related to the embedded DO-resumptive and the matrix subject, see (8c); this suggests that the topic XP does not originate in the c-command domain of the matrix subject (viz., the position of the RP). See also Uwalaka (1991: 199) for SCO effects under wh-movement in Igbo.

-

(8)

Focus fronting also reconstructs for idiom interpretation. The expression ‘to hit the teeth with the spoon’ in Igbo has a literal reading and the idiomatic reading ‘to eat.’ Focus fronting of ‘the spoon’ (which is a DO in Igbo, not a PP adjunct as in English) preserves the idiomatic reading. Under topicalization of ‘spoon,’ however, the idiomatic reading is lost. Assuming that idiom parts must be adjacent at LF to receive the idiomatic reading, the facts follow if focus fronting involves movement (and can thus reconstruct) but topicalization does not.

-

(9)

A hallmark of Ā-movement is that it licenses parasitic gaps (Engdahl 1985). (10a–b) show that focus fronting can license a pg in an adjunct clause in Igbo, but topicalization does not have this capacity, see (10c) (‘to prize sth.’ is expressed as ‘agree sth. to mouth’).Footnote 9 The following set of facts provides evidence for the claim that (10b) involves a true parasitic gap: (i) Both (10b) and (10c) can also have an overt pronoun (yá) instead of the gap in the adjunct clause; (ii) the gap variant in (10b) is only grammatical when an XP in the matrix clause has undergone Ā-movement, but not when the XP stays in-situ (wh-/focus-in-situ, possible in Igbo) or when it undergoes A-movement—the overt pronoun is possible in both cases; (iii) Igbo is not an (object) pro-drop language, we can thus rule out the presence of a silent pro in the pg-site in (10b) (see fn. 2 on subject pro-drop). Ogbulogo (1995: 139) and Uwalaka (1991: 201) provide pg-examples in other Ā-movement dependencies in Igbo.

-

(10)

We now turn to cyclicity effects. These are morpho-phonological changes along the path of Ā-movement (see Boeckx 2008; Abels 2012; Georgi 2014; van Urk 2015 for overviews). Amaechi (2020: Ch. 4) shows that Igbo is rich in (tonal) cyclicity effects. She argues that they qualify as reflexes of Ā-movement because they are triggered in all dependencies that involve Ā-movement (by the other tests in Table 1), but are absent (i) under base-generation, (ii) from constructions involving A-movement, and (iii) from sentences in which the focused XP stays in-situ. We will illustrate here the final H(igh) tone on crossed-over subjects (see also Robinson 1974; Tada 1995; Manfredi 2018). If an XP Ā-moves across a subject DP, the final tone of the subject becomes high. Take the subject Ézè in the baseline in (6a), which ends in a low tone. When the DO is focus fronted, this final tone on the subject obligatorily changes to high, see (11a) (and all focus fronting examples in this paper). No tone change occurs when the DO is topicalized, see (11b). (11c) illustrates that this tone change is triggered in all clauses of the dependency under long movement (the matrix subject Úchè ends in a low tone in declaratives, cf., (7a)).Footnote 10

-

(11)

We now turn to two language-specific Ā-movement diagnostics in Igbo. The first is the ban on extraction from perfective clauses (Nwachukwu 1976; Amaechi 2020: Ch. 4.6). Perfective aspect is expressed by a morphologically complex form consisting of a nominalizing prefix and suffixes; due to the nominalization, the DO of a perfective verb surfaces in the GEN-form, see (12). It is not possible to Ā-extract any XP (argument or adjunct) from a clause with perfective aspect, see (12b) for the attempt to focus the DO. But topicalization from a perfective clause is fine, see (12c).Footnote 11 Note that the ban on movement does not hold for A-movement and that focus/wh–in-situ is possible in clauses with perfective morphology. The effect thus diagnoses Ā-movement.

-

(12)

The second language-specific Ā-movement test is the occurrence of the ná-particle (glossed as prt). This particle must surface between the subject DP and the finite verb when an XP is Ā-moved from a clause that contains sentential negation. Negation is expressed by a high toned prefix (glossed as pfx) and the suffix ghi; both affixes agree in the ATR-value with the vowel of the verb stem; the suffix takes over the tone of the verb in addition. (13b) shows an example with DO-focus in a negative clause, where ná is compulsory. Just like the ban on extraction from perfective clauses, the ná-particle is not triggered in negated clauses in which A-movement applies, nor by focus/wh-in-situ and also not in dependencies that involve base-generation by other movement tests (Amaechi 2020), see the DO-topicalization example in (13c).

-

(13)

To summarize, there is comprehensive empirical evidence that Igbo has both movement and base-generation Ā-dependencies. An ex-situ focus XP moves from the gap site to its surface position; a topic XP is base-generated at the left edge of the clause and binds an RP (which is the thematic argument of the verb). Gaps and RPs are in complementary distribution in Igbo. Amaechi and Georgi (2019) propose that ex-situ foci and topics occupy different left-peripheral positions in a split CP à la Rizzi (1997). A focus XP targets the specifier of FocP, whose head is realized by the focus marker kà, see DO-focus in (14a); topics are base-merged in the higher SpecTopP, see a DO-topic in (14b). Evidence for this split comes from the observation that topic and focus XPs can co-occur in a clause, but only in the order topic ≻ focus.

-

(14)

The facts reported for DOs above carry over to other grammatical functions, viz., to subjects, indirect objects and adjuncts. Focus fronting of these elements also terminates in gaps, while topicalization requires an RP.Footnote 12 The properties reported here for focus fronting also hold for other Ā-movement dependencies such as ex-situ wh-question formation (which has the same syntax as focus ex-situ, see Uwalaka 1991; Amaechi and Georgi 2019), relativization (which involves empty operator movement, see Amaechi 2020: Ch. 2.3), and constructions based on them (clefts), see Goldsmith 1981; Amaechi 2020: Ch. 2–3). These works contain examples, tests, and further references.

4 Resumptives in Ā-movement dependencies

The data presented in the previous section suggest a correlation between Ā-dependency type and the choice of the element at the bottom of the dependency: Ā-movement leaves gaps; base-generation co-occurs with an RP. We will show in this section that this correlation breaks down in other contexts: Igbo also exhibits obligatory RPs under Ā-movement. We thus have to distinguish RPs in base-generation from RPs in movement dependencies.

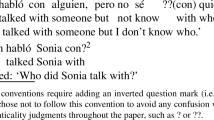

4.1 Evidence for a second type of RP

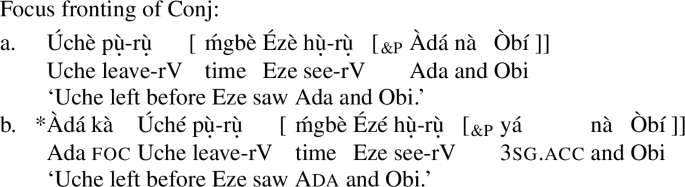

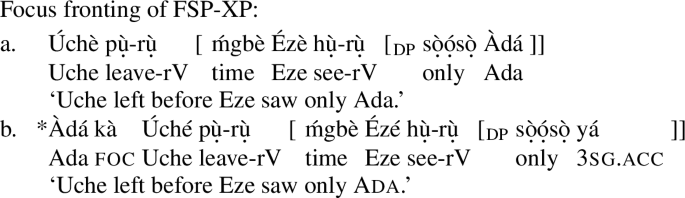

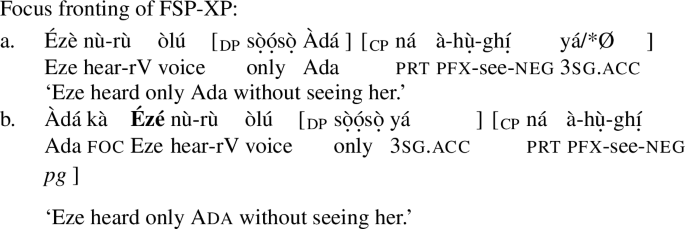

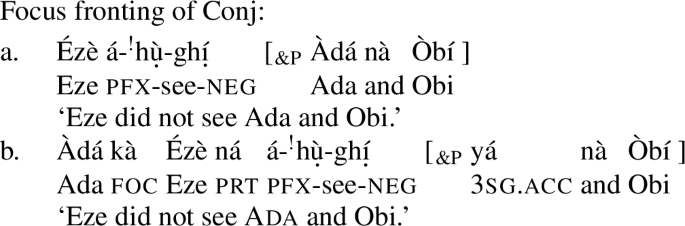

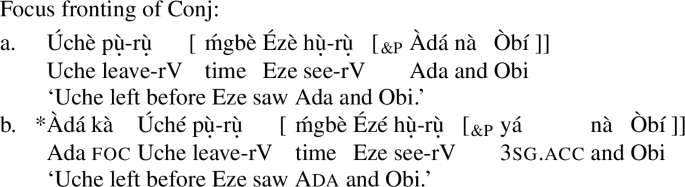

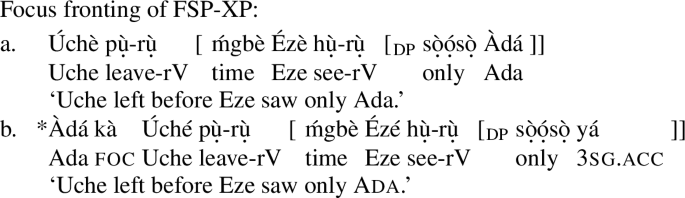

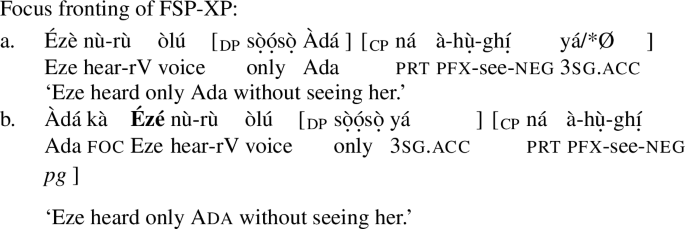

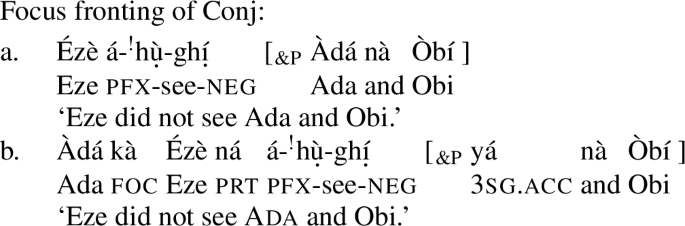

The findings reported in the last section are based on the fronting of core arguments of the verb. However, once we consider XPs in other functions, we see that even focus fronting sometimes requires the presence of an RP in Igbo. There are four contexts in which this happens: focus fronting of (i) the complement of a preposition (CompP, see (15)), (ii) a possessor (Poss, see (16)), (iii) a conjunct (Conj, see (17)), and (iv) an XP that a focus-sensitive particle associates with (FSP-XP, see (18)). In all these examples the focused XP originates in a constituent (PP, DP, &P) in direct object position.Footnote 13,Footnote 14

-

(15)

-

(16)

-

(17)

-

(18)

In all four contexts, focus fronting of the respective element is ungrammatical when the dependency terminates in a gap, as focus fronting otherwise does (see Sect. 3). Interestingly, the sentences become grammatical once an RP (bold-faced) is used. That RPs in Igbo can occur in dependencies that usually host gaps was first reported in Goldsmith (1981) for three of the contexts (CompP, Poss, Conj); Sells (1984) reuses his data.Footnote 15 An alternative strategy to form well-formed sentences in all four contexts is pied-piping of the entire PP, DP or &P; see (19) for a few examples (with gaps since we front a DO).

-

(19)

This appearance of RPs in a dependency that usually exhibits gaps is not a peculiarity of focus fronting. It holds in exactly the same four contexts in all other Ā-movement dependencies, viz., in ex-situ wh-questions, relative clauses, and clefts based on them. We do not illustrate these constructions here for reasons of space; see Goldsmith (1981) for some examples.

The first question that arises is whether focus fronting that leaves an RP has the same syntactic derivation as focus fronting that terminates in a gap, viz., whether both are the result of movement. One reason for thinking that their derivations might be different is the following: the XPs from which we extract in (15)–(18) (PP, DP, &P) are islands in many languages, at least for subextraction of certain elements (e.g., possessors in DPs). Extracting from them violates the Coordinate Structure Constraint, the Left Branch Condition (Ross 1967) or the ban on preposition stranding. Suppose these XPs are islands in Igbo, too. The usual movement derivation of focus fronting (leaving gaps) would thus be blocked. As a repair, the language might resort to the independently available base-generation strategy to form the dependency. Since base-generation always terminates in an RP in Igbo, we would also have an explanation for the occurrence of the RP in the four contexts. In fact, this scenario has been described for other languages, e.g., for Lebanese Arabic (Aoun et al. 2001) and Irish (McCloskey 1990, 2001, 2002): when a movement derivation is blocked by an island, the language employs the base-generation strategy instead. We can check whether this holds for Igbo, too, by applying the movement tests from Sect. 3 to the four RP-contexts (15)–(18). Table 2, an extended version of Table 1, summarizes the results; a third line has been added to illustrate the behavior of focus fronting that leaves an RP.

As Table 2 shows, we have to refute the base-generation hypothesis for focus fronting with RPs. Focus fronting always exhibits the typical properties of movement, regardless of whether it terminates in a gap or in an RP. In what follows, we illustrate this for extraction of CompP. In the examples, we extract a DP from the PP-complement of the verbs ‘believe in’ (see (15)) or ‘talk about,’ respectively (choice based on plausibility in the sentence). The tests are exemplified for the three other RP-requiring contexts in Appendix A. First, focus fronting of CompP is sensitive to CNP-islands, see (20). Extracting CompP from a relative clause leads to ungrammaticality even though an RP is present (a gap is out, too). This also shows that movement-derived RPs in Igbo do not have the capacity to repair islands.

-

(20)

Focus fronting that terminates in an RP also exhibits reconstruction effects such as Strong Cross-Over: a long-distance focus fronted CompP cannot be co-referent with the matrix subject pronoun, see (21).

-

(21)

Focus fronting of CompP also reconstructs for variable binding, as illustrated in (22). In the baseline, the variable can be bound by the universally quantified subject of the embedded clause, such that every mother believes in her own child. This reading is preserved when CompP undergoes focus fronting.

-

(22)

Furthermore, focus fronting that leaves an RP licenses pgs:

-

(23)

Focus fronting of elements that leave RPs also triggers the tonal cyclicity effect on subjects: the (underlying) final low tone of subjects along the movement path becomes a high tone. Compare, e.g., the a.-examples (baseline) in (15)–(18) (subject Ézè) with the respective ex-situ focus b.-examples (subject Ézé).

Finally, focus fronting of an XP that leaves an RP also triggers the two language-specific diagnostics for Ā-movement in Igbo: first, the dependency is blocked in clauses with perfective morphology; see (24) for an attempt to focus front CompP in such a context (as with gap-leaving focus fronting, extraction is possible when the verb occurs in the -rV-form instead).

-

(24)

Second, when RP-leaving focus fronting takes place from a negated clause, the particle ná must surface between the subject and the finite verb, see (25).

-

(25)

In light of this evidence, we conclude that focus fronting is always the result of movement, whether it leaves a gap or an RP. This holds for all Ā-movement dependencies in the language, viz., also for wh-movement and relativization, which require RPs in the same four contexts as focus fronting, though we do not illustrate this systematically here (see (26b) for an example of CompP relativization). This result falsifies Goldsmith’s (1981) approach to gaps vs. RPs in Igbo relativization: he proposes a non-movement analysis for both gap and RP contexts; the antecedent is base-generated at the left edge and binds an overt pronoun (RP) or a null pronoun (gap) at the bottom of the dependency. Sells (1984), who reanalyzes Goldsmith’s data, postulates that both gaps and RPs are derived by movement, in line with the present findings. However, these authors do not provide empirical evidence for their assumptions from tests such as those applied above.Footnote 16 The results also show that the speculation in our own previous work (Amaechi and Georgi 2019: 15) that the presence of the RP suggests that ex-situ conjuncts are base-generated rather than moved is wrong. Another important conclusion we can draw is that Igbo has two different types of RPs in Ā-dependencies: (i) RPs that occur at the bottom of a base-generation dependency (topicalization), and (ii) RPs that surface in the launching site of a movement dependency. Type-(ii) RPs are more restricted than type-(i) RPs in the sense that type-(ii) RPs only occur in the four contexts in (15)–(18), while type-(i) RPs also arise when the dependency involves core arguments of the verb. Finally, the evidence provided in this section shows that PPs, DPs and &Ps are not (absolute) islands in Igbo. This holds at least for the extraction of Poss (DPs) and of entire conjuncts (&P), though extraction of other material from these phrases is still blocked. For example, the possessum cannot be extracted from a DP in Igbo, and &P is still an island for subextraction from a conjunct. See fn. 22, 51, and Appendix B for a brief discussion of the semi-transparency of &P in Igbo and other languages, and the status of the CSC; Georgi and Amaechi (2020) discuss the CSC and other islands in Igbo. This result raises interesting questions about the source of cross-linguistic variation in islandhood, an issue that we will not address in this paper, however.Footnote 17

4.2 Typological considerations

That RPs cannot just occur at the bottom of base-generation dependencies, but also surface in the base position of Ā-movement is not a new insight, see among others Borer (1984) on Hebrew (free) relatives; Engdahl (1985) on Swedish; Aoun et al. (2001) on Lebanese Arabic; and Boeckx (2003) and Salzmann (2017: Ch. 3.1) for overviews of the literature on this topic. In fact, it has been argued before for a few languages that RPs in base-generation and in movement dependencies can co-exist in a single language: see Agüero-Bautista (2001) on Spanish; Aoun et al. (2001) on Lebanese Arabic; Bianchi (2004), e.g., on Italian; Alexandre (2012) on Cape Verdean Creole; Sichel (2014) on Hebrew; Panitz (2014) on Brazilian Portuguese; Korsah and Murphy (2019) on Asante Twi (object RPs); Scott (2020) on Swahili; and Yip and Ahenkorah (2021) on Asante Twi (subject RPs) and Cantonese. Given the evidence presented in this paper, Igbo can be added to this list.

Nevertheless, resumption in Igbo is remarkable in two respects. First, in the majority of the aforementioned languages with movement and base-generation resumptives the evidence is based on the distribution of RPs in relative clauses. This is related to the observation that cross-linguistically, RPs are most frequent in relatives and cleft structures based on them, but rarer in (mono-clausal) wh-movement constructions (Salzmann 2017: 180). In Igbo, we find RPs in all constructions involving Ā-movement, including focus and wh-movement. Second, Igbo is the first language with these two types of RPs for which we have comprehensive evidence from virtually all major movement tests as well as from language-specific movement diagnostics to support the split (see Table 2).Footnote 18 The main tests for dependency type employed in the resumption literature are island sensitivity and/or reconstruction effects, other tests are applied much less frequently.Footnote 19 In fact, Salzmann (2017: 206) concludes from his overview of the resumptive literature concerning the application of movement tests that “there is arguably not a single language which has been tested for all movement diagnostics. In other words, the empirical picture is quite incomplete” (see also Rouveret 2011). Moreover, he argues that some of the available data are inconclusive (due to the lack of full paradigms or ungrammatical examples). The present paper closes this gap; Igbo offers pervasive evidence for the co-existence of two types of RPs in a single language.

RPs in movement dependencies in Igbo are obligatory, viz., they are in complementary distribution with gaps across all contexts. Several properties have been associated with obligatory resumption cross-linguistically, at least as tendencies. First, the obligatoriness of movement-derived RPs is common; optional RPs freely alternating with gaps tend to occur in base-generation dependencies (Sichel 2014). Second, optional RPs, but not obligatory ones, often impose semantic restrictions on the RP-antecedent, viz., the antecedent must be specific/referential/D-linked, but cannot be quantified, non-D-linked, or occur in amount relatives; in addition, de dicto readings are not available in sentences with such RPs (see Doron 1982; Suñer 1998; Sharvit 1999; Aoun et al. 2001; Bianchi 2004). Igbo is a typical obligatory resumption language in this respect: there are no interpretative restrictions on the antecedent of a movement RP, as illustrated in (26a) for an amount relative clause (RC) whose head corresponds to a conjunct inside the RC (Conj-context), and in (26b) for focus fronting of a quantified CompP.

-

(26)

5 Modeling the emergence of RPs in movement dependencies

In this section we discuss how the occurrence of RPs in movement dependencies can be modeled. We adopt a spell-out approach according to which these RP realize the remnants of a partially deleted lower copy of the moved XP. We briefly address possible reasons for the restriction of the RPs to CompP, Poss, Conj, and FSP-XP (a detailed discussion can be found in appendix B). We conclude that full copy deletion is blocked in these four positions because of their prosodic strength. We also provide the structures of the RP-containing constituents, as they will be relevant in subsequent sections.

5.1 RPs as the spell-out of reduced copies

A prominent idea in the resumption literature that has been used to explain the obligatoriness of RPs, e.g., in CompP- and Conj-position, is that the extraction site is located inside an island (viz., PP, &P). Since the usual movement derivation (leaving gaps) is blocked, base-generation (terminating in an RP) is used instead. We have already ruled out this explanation for Igbo in Sect. 4: the empirical evidence shows that the dependency involved is movement.

Boeckx (2003), Müller (2014) and Klein (2016) develop movement accounts to RPs inside islands. In these approaches, the presence of an RP leads to a derivation in which an island ceases to block movement (Müller 2014), does not become an island in the first place (Klein 2016), or the derivation involves locality-insensitive operations (Boeckx 2003). While these approaches are compatible with the Igbo facts, the question arises why not all islands can be circumvented in this way. Recall that CNP (and other) islands cannot be repaired by RPs in Igbo, see (20) and see fn. 22. Hence, the question remains what makes the constituents in (15)–(18) special such that the presence of an RP allows subextraction from them, but not, e.g., from a CNP-island.

Type-(ii) RPs in Igbo thus require a proper movement account in which PPs, DPs, and &Ps are not (absolute) islands. Movement approaches to resumption that are in principle compatible with the Igbo facts are BigDP/stranding approaches (see, e.g., Aoun et al. 2001; Boeckx 2003), where the DP and its associated RP start out as one constituent from which the DP is subextracted, and approaches in which RPs are the spell out of traces/lower copies. We will pursue a spell-out approach for Igbo because it allows us to integrate phi-mismatches in resumption, which we will discuss in Sect. 6, more easily. In what follows, we briefly summarize the basic idea of the spell-out approach.

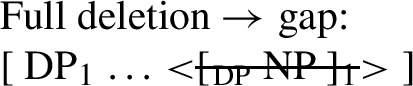

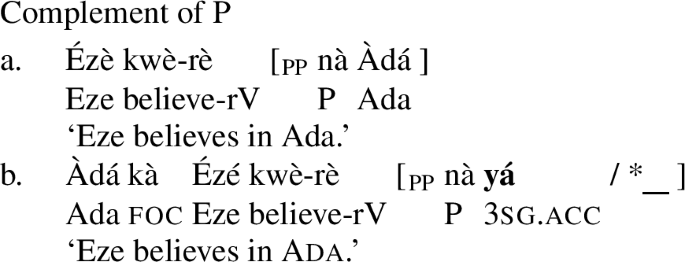

In spell-out approaches, which ultimately go back to Perlmutter (1972), RPs are the morphological realization of (parts of) a trace/lower copy. For concreteness, we adopt the implementation proposed in Pesetsky (1998); Landau (2006) (see also the application in van Urk 2018, and a system similar in spirit in Fanselow and Ćavar 2001): working with the copy theory of movement (Chomsky 1995), they assume that lower copies are usually subject to full deletion, which results in a gap, since no structure is left that could be pronounced. But if full deletion is blocked, only a subpart of the copy is deleted (partial deletion), and the remnants of the copy are pronounced as a pronoun.

How copy deletion proceeds is determined by PF-constraints that interact in an optimality-theoretic fashion. The two crucial constraints are recoverability and an economy constraint on pronunciation. The economy constraint (Econ) demands the deletion of copies; recoverability (Rec) requires that at least one copy is pronounced so that its content is recoverable. There are various definitions of these constraints, we provide two general ones below:

- (27)

Given the ranking Rec ≫ Econ, all copies but one are deleted entirely (full deletion). In Igbo, as in many other languages, the copy that is pronounced is the highest one, see (28) (lower copies are in angled brackets, deletion is indicated by a strike-through).Footnote 20 This results in an output with a focus fronted XP and a gap in the base position of this XP (as well as in potential intermediate landing sites), as we find it, e.g., under DO-focus fronting in Igbo.

-

(28)

-

(29)

Econ and Rec can interact with other constraints on pronunciation. If those constraints require the overtness of a copy in position P and are ranked above Econ, they prohibit full deletion of the copy in P. In particular, if P hosts a lower copy, this copy cannot be entirely deleted. In this case, Econ still enforces to delete a subpart of the copy in P so that only a small set of nodes remains that can be pronounced. We thus get partial deletion.Footnote 21 According to Pesetsky, the remaining structure surfaces as a pronoun since pronouns, which express phi-features, are the minimal representation of a nominal. See van Urk (2018) for a formal implementation of this idea, which we will discuss in Sect. 6, and Rouveret (1994) for a related proposal. The partial deletion analysis of RPs is inspired by Postal (1969); Elbourne (2001, 2005); Patel-Grosz and Grosz (2017) according to whom pronouns are the spell-out of D-heads in a DP with an elided NP-complement.

5.2 On the distribution of RPs in movement dependencies

A question we have not addressed so far is why RPs in movement dependencies are restricted to CompP, Poss, Conj, and FSP-XP in Igbo. Under a partial copy deletion approach, this amounts to the question what exactly the constraints ranked above Econ are that enforce the overtness of copies in these positions. Previous accounts of the distribution of RPs in Igbo are not convincing. Goldsmith (1981) adopts a base-generation account for all Ā-dependencies in the language and assumes that they terminate in a pronoun. Gaps result from the application of a rule that deletes this pronoun. When the deletion rule is suspended, the pronouns are realized overtly (= RPs). The contexts in which it is suspended are simply listed as exceptions in the structural description of the rule: it does not apply when the pronoun is contained in a DP (Poss, Conj) or a PP (CompP) (Goldsmith 1981: 386). Apart from the fact that the evidence in Sect. 4 argues against base-generation, Goldsmith’s analysis of the distribution of RPs basically restates the observation. Sells (1984) proposes that the choice between gaps and RPs is related to government: positions that are lexically or antecedent governed host gaps; those that are not governed must host RPs. The analysis requires the stipulation (noted by Sells 1984: 217) that P does not govern its complement in Igbo to account for RPs in CompP; besides, the status of government in current theorizing is unclear.

From a conceptual point of view, there are two desiderata on constraints that regulate the distribution of movement-derived RPs: Ideally, there should be a single constraint that covers all four contexts in Igbo in which these RPs occur. Second, since the contexts in which obligatory RPs surface across languages are rather uniform (Salzmann 2017: Ch. 3.2.), we should apply constraints that have been identified for other languages with a similar distribution of RPs. We thus need to compare the previous proposals in the literature and evaluate how well they are suited to capture the distribution of movement-derived RPs in Igbo. These proposals include minimal word requirements, affix/host requirements, a phonological EPP, an overtness requirement for oblique case, and an anti-locality-based approach. Since a detailed discussion of all proposals would lead too far afield, and since the question what triggers partial deletion is orthogonal to the main purpose of this paper (empirical evidence for two types of RPs in Igbo), we postpone it to Appendix B. The upshot is that hardly any of the previous proposals can capture all four contexts in a uniform way because there is either counter-evidence for some of the contexts, and/or no independent supporting evidence. The only approach, that, in our view, may cover all four contexts is one that takes them to be associated with phonological pronunciation requirements (the positions cannot be null), which are related to the prosodic prominence of the positions. We believe that this approach is the least problematic one. Crucially, nothing of what follows hinges on this choice.

5.3 The structure of the constituents that contain movement-derived RPs

Before closing the syntactic part of this paper, we will outline our assumptions about the structure of the constituents that contain movement-derived RPs in Igbo, viz., PPs, &Ps, DPs containing a Poss or an FSP. The structure of these constituents will be relevant in the discussion in Appendix B (the trigger of partial deletion) as well as in the analyzes of morphological mismatches in resumption that we address in Sects. 6 and 7. The structures we adopt are illustrated in (30)–(33); the RP-hosting positions are bold-faced.

-

(30)

-

(31)

-

(32)

-

(33)

We adopt the standard structure for PP: P takes a DP as its complement; we have no reason to postulate more projections in between these two elements.

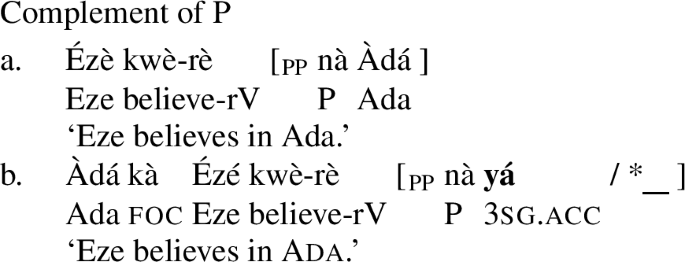

As mentioned in Sect. 2, possession is expressed in the associative construction in Igbo. In this construction, two nominal projections (which we represent as DPs) are juxtaposed on the surface. The DPs can stand in a number of semantic relations, possession being just one of them. The structure of the associative construction has received some attention in the Igbo literature. The general consensus is that the two nominal projections are syntactically linked by a functional head F: the second DP (DP2 in (31), possessor) is the complement of F, and the FP adjoins to the first DP (DP11 in (31), possessum). We follow the argumentation in Clark (1990: 258ff.) who identifies F as a preposition (Manfredi 1993 and Goldsmith 1976: 183 call it a case-related head K(ase) or “Genitive”); FP is thus a PP, see (31). Since Poss occupies the position of DP2, which is the complement of a preposition, Poss extraction is an instance of CompP-extraction. While the head P is segmentally empty in the associative construction, it hosts a high tone; the effects of this tone will be discussed in Sect. 7.

Turning to the structure of nominal (DP) coordination, we adopt an asymmetric &P structure for Igbo. This means that the second conjunct (DP2 in (32)) is the complement of the coordination head &, while the initial conjunct (DP1 in (32)) is base-merged in the specifier of &. Empirical evidence for the asymmetric (and against a symmetric) structure comes from the observation that a variable in the second conjunct can be bound by the first conjunct, but not vice-versa. This suggests that the first conjunct c-commands the second conjunct (see Progovac 1998 for an overview of &P-structures). One may wonder whether what we have called a nominal coordination in this paper may actually be a comitative that contains a PP. The Igbo equivalent of Obi and Ada would then literally be Obi with Ada. This seems plausible given that the coordinating element nà is homophonous with the preposition nà (used, e.g., in (15)). However, applying syntactic and semantic tests for comitatives vs. &Ps, we do not find any evidence for the comitative hypothesis.Footnote 22 We thus do not postulate a PP inside the &P (and the extraction of the seond conjunct–to the extent that it is possible at all, see fn.16–could thus not be subsumed under CompP-extraction). The structure of coordination will be crucial in Sect. 6 where we analyze phi-mismatches in resumption. In this context, we will add more projections above &P, but we will keep the basic asymmetric structure of &P. Lastly, we consider FSPs and their associated DP. Given that the FSP and its DP (i) co-occur in-situ, (ii) have to be adjacent in-situ, and (iii) can be moved as a unit (see (19c)), we take them to form a constituent. It is debated whether FSPs are adjuncts to the DP or whether they are heads that take the associated DP as their complement. It is not easy to provide empirical evidence for/against one of these views. We adopt the latter approach with FSPs being heads, see (33) (and also Aboh 2004; Corver and van Koppen 2009 for the postulation of a FocP in nominals). The reason is that this assumption makes it easier to integrate the FSP-XP position (a complement position in (33)) in possible explanations about the trigger of partial deletion, see Appendix B. But nothing in the main text (evidence for two types of resumption, analysis of the morphological mismatches between antecedent and RP) hinges on this choice. We will thus continue to label the FSP+DP constituent as a DP in what follows.

6 Phi-mismatches in Igbo

In the first part of this study we have investigated the syntax of resumption, i.e., the derivation and distribution of RPs. In the second part, we turn to its morphological properties. Recall from Sect. 2 that RPs in Igbo are taken from the personal pronoun paradigm, repeated in (34); personal pronouns in Igbo inflect for person, number and what we have provisionally called case.

-

(34)

Igbo personal pronouns

Interestingly, the antecedent and its associated RP do not always match in features in Igbo. The languages exhibits mismatches in phi-features (current Section) and in “case” (Sect. 7). The phi-mismatch is important because (i) it provides further evidence for the existence of two types of RPs in Igbo, (ii) it favors a partial copy deletion account of movement-derived RPs over a BigDP approach, and (iii) it is relevant in terms of cross-linguistic variation since the Igbo mismatch pattern is more complex than previously described patterns in that it is sensitive to the type of antecedent. To capture this pattern, we propose an extension of van Urk’s (2018) partial copy deletion based approach that makes use of dynamic rather than static deletion domains.

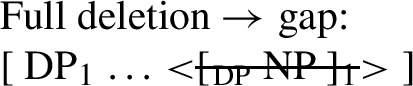

6.1 Conditions on phi-(mis)matching

In all RP-examples presented so far in this paper, the antecedent was a 3sg proper name. The corresponding RP was also 3sg, which suggests that RP and antecedent must match in phi-features. In fact, this holds for RPs in base-generation dependencies. (35) illustrates this for a 2sg and a 1pl DO topic (recall that even core arguments of the verb are resumed under topicalization); using an RP that mismatches in person or number leads to ungrammaticality.

-

(35)

The picture is more complicated with RPs in Ā-movement dependencies since we find a split between pronominal and lexical N(oun) antecedents. With a lexical N antecedent, the RP has to match in phi-features—though this is only observable for number since nouns are always 3rd person. (36) exemplifies this for a common noun antecedent. Using any non-agreeing RP leads to ungrammaticality.Footnote 23 In what follows, we illustrate phi-mismatches in Ā-movement chains with extraction of CompP, but the generalizations also hold for extraction of Poss, Conj, and FSP-XP.

-

(36)

With pronominal antecedents, however, the RP can only be the 3sg pronoun, regardless of the person and number values of the antecedent, see (37a). Using a fully or partially agreeing RP with non-3sg extractees results in ungrammaticality; (37b) illustrates this for the 2pl pronoun. The only previous mention of the use of a 3sg RP in a dependency with a local person pronoun antecedent in Igbo can be found in Goldsmith (1981: 385, fn.5) for focus fronting in a cleft.

-

(37)

Note that focus fronting of personal pronouns is fine in Igbo, as shown in (38) (with DO-focus and thus a gap). And we saw above that RPs can in principle have a feature specification other than 3sg in the language (with topics and lexical N foci as antecedents).The mismatch in (36) can thus not be related to independent restrictions on the shape of RPs or on focus fronting of pronouns.

-

(38)

Further complications arise in &Ps: Focus fronting of a coordinated DP always requires a fully matching RP, regardless of whether the conjuncts are all lexical Ns, all pronouns, or a mix of lexical Ns and pronouns. Thus, even if two pronouns are coordinated, the RP that resumes the &P must be fully matching—although RPs that refer to simple pronoun antecedents have to mismatch, see (37). Full matching with coordinated antecedents actually means “resolved matching” in Igbo (cf. resolved agreement, Corbett 2006: Ch. 8.1), i.e., the RP matches the resolved phi-features of the coordination: the RP is always plural (number resolution) and its person feature is determined by the person scale 1 ≻ 2 ≻ 3 (the RP matches the more prominent person value). For instance, a coordination of a 2sg and a 3sg conjunct results in a 2pl RP; it is not possible to use an RP that (a) fully or partially mismatches the &P’s resolved features, or that (b) fully matches only one of the conjuncts. (39) illustrates a few combinations. The coordination facts constitute a novel observation for Igbo and more generally also for languages with phi-mismatches in resumption.

-

(39)

To summarize, there is obligatory phi-matching between the antecedent and its RP, unless the antecedent is a simple (i.e., uncoordinated) pronoun that heads a movement chain. Coordinated antecedents require resolved matching on the RP. Table 3 gives an overview of the pattern with an RP in the ACC-form (viz., in CompP, Conj, or FSP-XP position). The only difference in Poss-position is that the RP surfaces in the GEN-form.

The phi-(mis)match pattern in Igbo provides further evidence for the co-existence of the two types of RPs that we have argued for in the preceding sections: Phi-mismatches are only possible with movement-derived RPs, but not with RPs in base-generation dependencies. The mismatch must thus also reflect the different derivational histories of the RPs. In what follows, we pursue an account of the Igbo pattern that restricts phi-mismatches to movement chains.

6.2 Phi-mismatches in resumption: State of the art

Phi-mismatches between an XP and a doubling element such as a clitic or an RP in movement dependencies are well-attested in the literature: see Poletto (2000); Boeckx (2003); Adger (2011); Rouveret (2011); van Urk (2018) for overviews. There are, however, only a few proposals in the literature that try to account for morphological mismatches between several overt chain links. One type of account is designed to model mismatches where the moved element is morphologically less complex than the element it is copied from, see among others van Craenenbroeck and van Koppen (2008); Barbiers et al. (2010); Boef (2012) on partial copying in wh-chains and subject clitic doubling, respectively. These approaches cannot be applied to Igbo since Igbo exhibits the opposite pattern: it is the lower copy that is morphologically less complex (RP) than the moved element. The first explicit proposal of this type of mismatch in movement-derived resumption is presented in van Urk (2018) for pronoun copying in Dinka; his approach is extended to Swahili in Scott (2020) (see fn. 29) as well as to Asante Twi and Cantonese in Yip and Ahenkorah (2021).Footnote 24 Before we discuss this approach, we will summarize cross-linguistic generalizations on phi-mismatches in resumption from the literature so that we can evaluate how (un)usual the Igbo mismatch pattern is.

First, phi-mismatches are attested both in base-generation dependencies (Adger 2011) and in movement dependencies (van Urk 2018). In the few languages that have been shown to have RPs in both types of dependencies (see Sect. 4.2), we may ask whether mismatches can affect RPs in both contexts: This has been addressed in Scott (2020) for Swahili and in Yip and Ahenkorah (2021) for Asante Twi (subject RPs) and Cantonese: these authors report that phi-mismatches are only possible with RPs in Ā-movement chains, just like in Igbo. Second, regarding the degree of mismatching, the following patterns are (*not) attested for the features person and number:

-

(40)

The Igbo mismatch with pronominal antecedents in movement chains corresponds to mismatch pattern (40c). In this respect, the Igbo pattern is not exceptional. What is remarkable, though, is the language-internal variation, viz., the fact that some antecedents (lexical Ns) exhibit full matching (or a person-only mismatch—ambiguous because lexical Ns are always 3rd person), while others (pronouns) require a mismatch in person and number. Such variation has not been described for any of the other languages with phi-mismatches in resumption in the literature—apart from cases of optionality between two patterns with the same type of antecedent, see, e.g., Scott 2020; Yip and Ahenkorah 2021). The patterns in (40a) were established based on cross-linguistic variation. That a split between lexical N and pronominal antecedents has not been reported so far is also due to the fact that (i) many mismatches reported in the literature are person-only mismatches, but we cannot detect a potential person mismatch with lexical N antecedents, which are always 3rd person; and (ii) personal pronoun antecedents are often not tested at all. In the cases where lexical N and pronominal antecedents have been considered, no split is reported (e.g., Scott 2020; Yip and Ahenkorah 2021). Moreover, resumption with coordinated antecedents has not been addressed in languages with phi-mismatches (though it has for some cases of clitic-doubling). Language-internal variation in phi-mismatches as in Igbo may thus be more wide-spread, this has just not been thoroughly investigated.

The first explicit account of the patterns in (40) is presented in van Urk (2018). His analysis also offers an understanding why phi-mismatches in some languages only affect movement-derived RPs, but not those in base-generation dependencies (as, e.g., in Swahili and Igbo). The account crucially relies on partial copy deletion. In this subsection, we will briefly summarize van Urk’s basic ideas in order to understand why, in our view, his account favors a partial copy deletion approach over a BigDP-approach to resumption in Igbo. We will discuss the details of van Urk’s phi-mismatch analysis in Sect. 6.3.

Recall from Sect. 5.1 that under the partial copy deletion approach to resumption, RPs are the realization of the remnants of a DP-copy that remain when a subpart of the DP-copy is deleted. In that section, we illustrated the idea with a very simple DP-structure [\(_{DP}\) D NP ]; when NP undergoes partial deletion, the surviving D-head is realized as a pronoun, see (29). Crucially, van Urk assumes—following developments in the literature on the internal structure of nominals—that phi-features in the DP are encoded on a separate projection between D and N, see the simplified representation in (41):

-

(41)

[DP D [PhiP Phi NP ]]]

In a nutshell, van Urk proposes that partial copy deletion may affect nodes between NP and DP such as PhiP in (41). If partial deletion targets phi-hosting projections, the RP that realizes the remaining structure cannot express phi-features anymore and must be a default from; the result is a phi-mismatch between the antecedent and the corresponding RP. Crucially, the trigger for the mismatch is partial copy deletion. Since this operation affects copies, which are only created in movement dependencies, phi-mismatches are not expected under base-generation (see also Scott 2020 for this point). This is the distribution we find in Igbo and Swahili. We believe that BigDP/stranding-approaches, which also derive RPs via movement, are less well-suited to capture this: in a BigDP, where the antecedent (XP) and the RP (D) start out as one constituent [DP D XP ], it remains unclear why subextraction of the XP should result in a phi-mismatch on the stranded pronoun; the pronoun is neither affected by movement nor by copy deletion. For this reason, we favored a copy deletion over a BigDP approach to resumption in Igbo in Sect. 5.1.Footnote 25

6.3 Previous accounts of phi-mismatches and challenges posed by Igbo

The first detailed account of phi-mismatches in movement-derived RPs is presented in van Urk (2018). He is concerned with a person-only mismatch (pattern (40b)) in Dinka: Movement of plural nominals (lexical Ns and pronouns) triggers a plural pronoun at crossed vP-edges; this pronoun must be 3rd person, also with local person antecedents. Van Urk makes the following assumptions about the structure of nominals and copy deletion to derive this pattern:

-

(42)

-

(43)

-

(44)

The Dinka person mismatch is derived as follows: the economy constraint Econ in competition-based spell-out approaches (see Sect. 5.1) demands full copy deletion, viz., deletion of the highest phase. This is the node KP, the topmost node in the nominal’s extended projection; the result is a gap. If a higher ranked Rec-constraint blocks full deletion, deletion can target the next lower phase, viz., nP (= partial deletion). Partial deletion is always possible for copies of lexical Ns since, by (42b-iii), nP in lexical Ns is always a phase. Dinka is assumed to be a language in which nP is also a phase in pronouns, thus partial deletion can also affect nP there. As a result of nP-deletion, we create a structure that has no more person information (since Person is located on n, see (42a-iii)). With lexical N copies, the resulting structure is furthermore pronoun-like in the sense that it lacks a lexical root (since the root is dominated by nP); recall that the presence of the root is the only difference between nouns and pronouns (see (42a-i)). The remnants of lexical N and of a pronominal copy can thus only be realized by an RP that does not express person features. This gives rise to a person-only mismatch with pronominal copies (pattern (40b)). Given that lexical Ns are 3rd person anyway and that the default RP used in mismatching configurations is 3rd person (in Dinka and other languages), the result for lexical N copies is ambiguous between a person mismatch and full matching (pattern (40a)). This derives the Dinka facts.Footnote 26

Van Urk further discusses some cross-linguistic variation in phi-mismatches. In languages in which nP is not a phase in pronouns partial deletion cannot apply, since there is no lower phase present in the structure, and deletion can only target phases (see (42b-i)). Hence, nothing is deleted from the pronominal copy at all and we get a fully matching RP (pattern (40a)).Footnote 27 Finally, the hitherto unattested pattern in (40d), i.e., a number-only mismatch, is ruled out in his system since deletion of a projection containing number (if possible at all given (42b)) would always lead to a deletion of the projection that hosts person, since NumP dominates nP (see (42a-iii)).

This is an elegant system that also provides a handle for cross-linguistic variation. However, when we try to apply it to Igbo, in which several patterns co-exist, some problems arise. Recall that in Igbo movement chains, lexical N antecedents require number-matching RPs. Just like in Dinka, this is ambiguous between full matching (pattern (40a)) and a person mismatch (pattern (40b)) since nouns are 3rd person. The facts can be derived in van Urk’s system if we treat them as a person mismatch induced by deletion of nP (always a phase in lexical Ns), see (45) (deleted structure is boxed). Pronominal antecedents, on the other hand, require an RP that mismatches in person and number in Igbo (pattern (40c)). This would require deletion of a projection that contains both person and number information, e.g., of NumP, see (46), which is not a phase, though, according to van Urk.

-

(45)

-

(46)

What is problematic for an extension of van Urk’s approach to Igbo is thus the person-number-mismatch with pronominal antecedents (pattern (40c)). In fact, he does not discuss this pattern. To derive it, NumP would have to be turned into a phase (given (42b-i)). Various technical options come to mind to achieve this: (a) phase extension from nP to NumP through a unification of n and Num (e.g., via head-movement of n to Num à la den Dikken 2007 or merger of n and Num), or (b) postulation of a single head that hosts both person and number features from the beginning, rather than starting with two separate heads. These solutions work from a technical point of view. The major problem, however, is the language-internal variation in Igbo: whatever mechanism one adopts to make NumP a phase in pronominal copies in Igbo must not apply to copies of lexical Ns, where we still want to delete nP, and not NumP, since lexical N RPs do match in number. We would thus add another difference between lexical Ns and pronouns on top of the structural one introduced in (43)–(44): a difference in which nodes are/become phases, viz., nP in lexical Ns vs. NumP in pronouns (i.e., the mechanism only applies in pronominal but not in lexical N structures). This is certainly not desirable.

Alternatively, we can try to apply slightly different partial deletion algorithms, which were proposed to extend van Urk’s approach to other languages: Scott (2020) and Yip and Ahenkorah (2021) assume that partial copy deletion does not target phases but is rather subject to MaxElide, i.e., it deletes the largest constituent possible. For Scott (2020) this is a constituent such that the remaining structure can still be realized by a VI (see fn. 33 for details). For Yip and Ahenkorah (2021) this constraint enforces deletion of everything but the label of the entire nominal constituent; since this constituent is a DP for Yip and Ahenkorah (not a KP as for van Urk), only the D-head remains after partial deletion. These algorithms run into similar problems with respect to language-internal variation in Igbo as van Urk’s proposal: While they can derive the occurrence of the phi-invariant, most reduced form (the 3sg pronoun yá) as an RP with pronominal antecedents in Igbo (assuming that it realizes the topmost head of D of the nominal projection), we would expect these MaxElide-based deletion algorithms to have the same output in lexical N copies. But this is not the case in Igbo: number information remains in those copies, unlike in pronominal ones. The split between lexical Ns and pronouns in Igbo thus forces us to revise the algorithm that determines how much structure partial deletion affects. The alternative, but undesirable, move would be to stipulate that the partial deletion domains simply differ from language to language – and even between noun types within a language to derive the Igbo-internal split. In the following subsection, we present a version of van Urk’s analysis that is solely based on structural differences between lexical Ns and pronouns, while the deletion rule will be constant across languages. The crucial innovation will be a dynamic (context-sensitive) rather than a static deletion rule; this rule will produce deletion domains of different sizes within and across languages.

On top of the questions posed by the split between lexical Ns and pronouns, we also have to integrate coordinated antecedents in Igbo. Recall that full (resolved) matching obtains regardless of whether the conjuncts are lexical Ns or pronouns, this distinction in uncoordinated antecedents is neutralized. It is, in fact, a challenge for all spell-out approaches to resumption to explain how (the copy of) a complex structure like a coordination is reduced to a simple pronoun under partial deletion rather than to a coordination of pronouns. A lot more structure seems to be deleted in copies of coordinations than in simple (pro)nouns. The dynamic deletion approach is able to derive this pattern, too.

6.4 Towards a solution: A dynamic deletion domain approach

The task is to provide an account of the split in phi-mismatching between lexical N and pronominal copies in Igbo that, ideally, does not require differences other than structural ones between these types of nominals. We want to avoid, for example, to simply restate in the deletion rule the observation that the nodes that are deleted in lexical Ns differ from those deleted in pronouns (and which concrete nodes are deleted). In addition, we need to answer the question how a coordination is reduced to a simple pronoun in resumption contexts in Igbo, while the phi-information from all conjuncts is preserved on the RP (resolved matching). Furthermore, the account should be flexible enough to cover the attested cross-linguistic variation. In particular, we want to derive the following patterns of phi-mismatches in movement-derived resumption with different kinds of antecedents, see Table 4 (the languages listed as ?1, ?2, and ?3 are unattested but logically possible patterns; the others are attested).

First, there are languages in which all nominals trigger the same phi-(mis)match on an RP under Ā-movement. For these we can expect the three (mis)match patterns listed in (40) (see the first three lines in Table 4): (i) The RP exhibits a person-only mismatch, while it inflects for number—this is the case in Dinka and Swahili (in the latter the RP also reflects gender, see fn. 33). (ii) the RP mismatches in person and number, i.e., we get an invariable default RP—this is the pattern in Akan (for subject resumptives) and Cantonese. (iii) There is no mismatch, viz., the RP fully reflects the phi-features of its antecedent (line ?1 in Table 4); we are not aware of convincing cases of pattern (iii) in the literature, mainly because the behavior of pronominal antecedents has not been checked, and/or because it is not clear whether the dependency that leaves these RPs actually involves movement (not enough tests applied, contradictory results from different tests), see Salzmann (2017: Ch. 3.1).Footnote 28 Second, there are languages in which the RPs associated with a lexical N and pronominal antecedent, respectively, exhibit different (mis)match patterns. Igbo is the first language for which we have found such a split; in this language lexical N antecedents relate to fully matching (ambiguous with person-only mismatching) RPs, while pronominal antecedents leave RPs that mismatch in person and number. Other lexical N/pronoun splits are logically conceivable, but only two of them will give rise to a morphological distinction between RPs related to lexical Ns vs. pronouns (considering only inflection for person and number, see lines ?2 and ?3 in Table 4): these would be languages in which RPs with lexical N antecedents mismatch in number and person (though person is not morphologically visible for nouns) and we thus get a phi-invariant default RP, while RPs associated with pronominal antecedents mismatch either in person only (still inflecting for number) or fully match in person and number. It remains to be seen whether such languages exist. We will come back to this typology in Sect. 6.4.2 and discuss which of the so far unattested patterns is expected (not) to exist under our revised partial deletion algorithm.

6.4.1 Deriving the split between lexical Ns and pronouns in Igbo

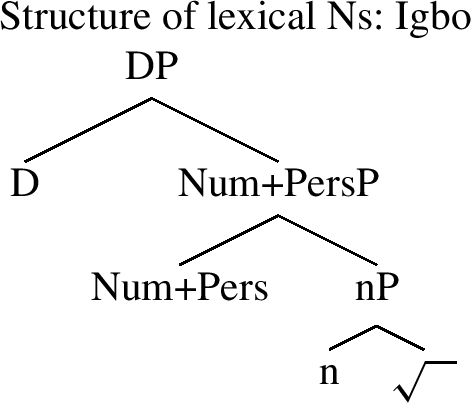

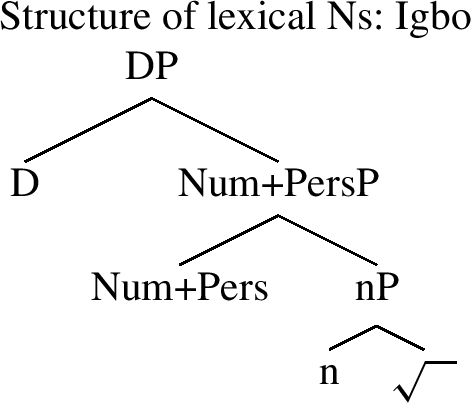

We adopt van Urk’s basic idea that phi-mismatches in movement-derived resumption arise when partial copy deletion targets nodes that host phi-information. We diverge, however, in (a) the presence of n in pronouns, (b) details regarding the location of phi-features, and most crucially (c) in the definition of partial deletion domains to account for the Igbo data. As for (a), we follow the proposal about the structural difference between nouns and pronouns in Moskal (2015a,b) more closely. She proposes that nouns contain a lexical root and the nominalizing head n (plus other functional heads in the extended projection), while pronouns lack the lexical root + the n-shell. Thus, there is no n in pronouns. As for (b), we assume that the phi-feature person is not located on the root-categorizing head n in lexical nouns, as proposed in van Urk (2018); rather person is represented on a separate head (above n), just like number. Furthermore, rather than seeing nominals as projections of K, we follow the view that they are D-elements, viz., the topmost projection is DP (see Abney 1987; and also Adger 2011; Scott 2020; Yip and Ahenkorah 2021 on the structure of nominals that are reduced to RPs). (Whether a K-head is present in the structure as well is irrelevant; we will show in Sect. 7 that it is not clear whether Igbo actually has (different) abstract case(s) at all.) Nothing in the analysis of phi-mismatches hinges on replacing KP by DP. But it allows us to represent the idea that pronouns realize D-heads in a DP with an elided subdomain, alluded to in the description of the partial copy deletion approach in Sect. 5.1, more directly. The basic structure of lexical Ns and pronouns that emerges from these assumptions is illustrated in (47):

-

(47)

-

(48)

To account for the cross-linguistic variation in 4, we assume that heads that belong to the same extended nominal projection in (47) and (48) can be bundled in some languages, i.e., instead of having a number of separate heads, e.g., H1 and H2 (and their projections), there can also be only a single head that bears all the features of these individual heads (H1+2, projecting H1+2P). Whether and how many heads are bundled is language-specific, but the bundling affects the heads in all nominals (lexical N and pronouns) alike in a given language. We will illustrate the range of bundling possibilities and the resulting mismatch patterns in Sect. 6.4.2. To generate the Igbo pattern, we need to assume that the Person and the Number head are bundled, as shown in (49) and (50).Footnote 29

-

(49)

-

(50)

Turning to the morphological side of resumption in Igbo, we take RPs to realize the functional head D. Given that phi-information is not hosted on D in the structures in (49) and (50), we assume that the pronouns do not (primarily) express person and number features; rather, these features, locally available on the structurally adjacent Num+Pers-projection, serve as context restrictions on the realization of D (secondary exponence). The phi-mismatch with local person/plural pronominal antecedents, which results in the presence of the 3sg pronoun as RP, suggests that this 3sg pronoun is the default pronoun; this default form is neither sensitive to person nor to number features. It can thus also be used when no phi-information is locally available. Using a 3sg pronoun may thus reflect the absence of phi-feature information in the underlying structure. (51) provides a list of RP-exponents (in the ACC-form) that reflects these assumptions. Note that we will add two exponents to this in list Sect. 7, but the specification of the exponents listed here will not change.

-

(51)

Vocabulary items for RPs in Igbo (to be extended)

-

a.

/ḿ/ ↔ [D] /

\I[Num+Pers 1sg]

\I[Num+Pers 1sg] -

b.

/gí/ ↔ [D] /

\I[Num+Pers 2sg]

\I[Num+Pers 2sg] -

c.

/yá/ ↔ [D]

-

d.

/àny

/ ↔ [D] /

/ ↔ [D] /  \I[Num+Pers 1pl]

\I[Num+Pers 1pl] -

e.

/

/ ↔ [D] /

/ ↔ [D] /  \I[Num+Pers 2pl]

\I[Num+Pers 2pl] -

f.

/há/ ↔ [D] /

\I[Num+Pers pl]

\I[Num+Pers pl]

-

a.

We adopt a realizational model of morphology, for concreteness Distributed Morphology (Halle and Marantz 1993, 1994), in which exponents (or vocabulary items, VIs) pair abstract morpho-syntactic features with phonological information in the post-syntactic component; i.e., there are no phonological features present on terminals in the syntax. On the PF-branch, a head H is paired with the most specific VI that has a subset of the morpho-syntactic features of H (Specificity Principle). We assume that context specifications count for the calculation of specificity. Thus, if two VIs are the primary exponents of the same features, it is the VI with more matching context features that wins the competition. Given the phi-insensitivity of the exponent /yá/ in (51), this VI is compatible with all person-number combinations on Num+Pers but it is usually blocked by the more specific VIs with context phi-specifications. Only if phi-features are not available, e.g., because they are deleted under partial copy deletion, can /yá/ surface.

We now turn to the major innovation of our proposal: point (c), the question how much structure is deleted under partial deletion. We saw that previous proposal where partial deletion targets a fixed set of nodes (e.g., phases) or operate on the basis of MaxElide are difficult to reconcile with the split between lexical and pronominal antecedents in Igbo, since they seem to require the deletion of different XPs in these nominals. We propose to replace van Urk’s (2018) static definition of the deletion domain with a dynamic definition. Thus, it is not pre-determined which node is affected by partial deletion (always KP or nP / always everything but the topmost head). Rather, the size of the deletion domain depends on the structural context. We propose the partial deletion rule in (52) for nominal projections:

-

(52)

Dynamic partial deletion (DPD)

Partial deletion applied to the copy of an XP deletes the lowest functional projection in the extended projection of XP.

When applied to the structures of lexical Ns (49) and pronouns (50) adopted for Igbo, we get the following results (the deleted domain appears in a box):

-

(53)

-

(54)

The lowest functional projection in the extended projection of a lexical N-DP is nP, while it is Num+PersP in a pronominal DP. Thus, phi-information in Num+Pers remains available for VI-insertion in lexical N copies in Igbo, whereas it is absent in pronominal copies. As a consequence, the VIs with phi-specifications in their context cannot be inserted into the remnants of a pronominal DP; the only VI that fits is the default one, viz., /yá/. This is why pronominal antecedents in movement chains must be resumed by a 3sg RP in Igbo, regardless of the phi-features of the antecedent. The result is a mismatch in person and number when the antecedent is local person and/or plural (pattern (40c)). Since Num+PersP in lexical N copies survives partial deletion, we are—descriptively speaking—dealing with a fully matching RP in this context (pattern (40a), though the 3rd person VIs are not specified for person features). Dynamic deletion thus successfully derives the split between lexical N and pronominal antecedents in Igbo resumption.Footnote 30

6.4.2 Deriving (the limits of) variation in phi-mismatches

In this subsection, we address the question how well the DPD-approach can account for the cross-linguistically attested (and expected) variation as summarized in Table 4. We will show that it can in fact derive all attested patterns with the same DPD-rule, the different patterns being only due to structural differences related to the bundling of heads in the nominal spine. At the same time, the approach excludes the so far unattested patterns—all other things being equal. Recall that we assumed that languages vary in whether heads in the nominal extended projection are separate, as in (47) and (48), or whether and how they are bundled. For Igbo we proposed PersP+NumP bundling. If these projections remain separate and we apply the DPD-rule in (52), we derive the Dinka/Swahili pattern, see (55) and (56):

-

(55)

-

(56)

The DPD-rule deletes nP in lexical N copies and PersP in pronominal copies, while the number projection remains in both. This results in RPs that can morphologically express number but not person. Lexical N copies still have a person projection after partial deletion, but since they are always 3rd person, the morphological result is indistinguishable from a person-only mismatch.Footnote 31

Another logical possibility is that bundling involves all heads in a nominals’ extended projection except the topmost one (D). This will give rise to the structures in (57) and (58): Num, Pers and n are bundled on a single head in lexical Ns, and Num and Pers are bundled in pronouns (there is no n in pronouns). When we apply the DPD-rule in (52) to these structures, it deletes a projection that both person and number features in both types of nominals. As a result, the RP that realizes the remaining structure is a default VI that does not reflect phi-features.

-

(57)

-

(58)

This completes the derivation of the three attested patterns in Table 4. There are more bundling options, but they will not produce new patterns. If, for example, all heads in the extended nominal domain were bundled, incuding D (D+Num+Pers(+n)), the DPD-rule would delete the entire DP; the result would be indistinguishable from full copy deletion and would thus create gaps instead of RPs, hence, a language in which movement never leaves RP. And if only a subset of the upper heads are bundled such that the bundle does not include the lowest functional head in the nominal spine, the DPD-rule will not affect this bundle. This is what happens in Igbo lexical N copies, see (53). Likewise, if D+Num were bundled in pronouns without Pers, we still derive a person-only mismatch, as in Dinka pronouns, see (56).