Abstract

This paper presents a novel account for the optionality of negative concord observed with neither...nor coordinations, in an otherwise strict negative concord language—Turkish. I argue that the apparently optional negative concord is a surface phenomenon that can be traced back to a structural ambiguity arising from the type-flexibility of coordination operators. The semantic type of the coordination affects its syntactic position relative to the Turkish NegP, which results in different surface facts: whenever the neither...nor coordination is of a generalized quantifier type, it originates in the vP below the NegP, akin to other negative concord items like nobody, triggering negative concord with sentential negation; whenever it is a propositional coordination, it contains the NegP position, and there is no negative concord. We can account for this exceptionally optional negative concord phenomenon by seamlessly importing these facts into an existing negative concord architecture (Zeijlstra 2004, 2012), with no significant modifications. This reductionist analysis contrasts with alternative approaches that explain optionality by adding complexity to the mechanics of the negative concord system (Şener and İşsever 2003 for Turkish; Szabolcsi 2018a for Hungarian). Finally, this account crucially relies on a theory of coordination operators as type-flexible, and therefore contributes an argument against a view of coordinators as having a rigid propositional type (Hirsch 2017; Schein 2017).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

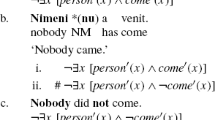

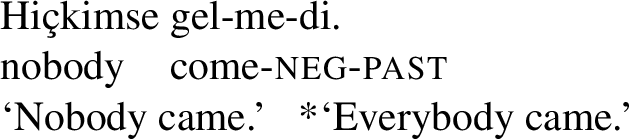

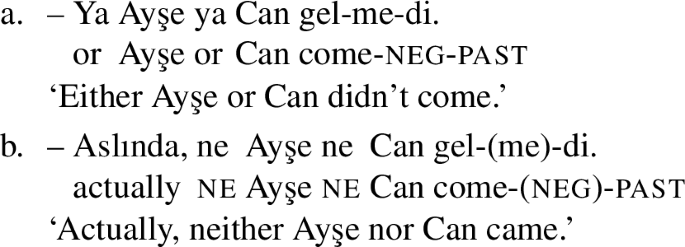

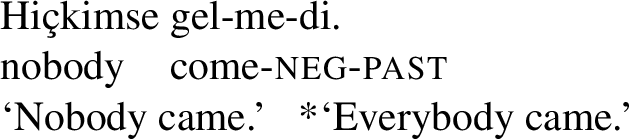

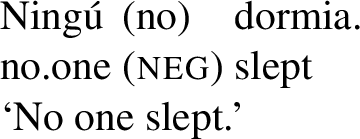

Negative Concord (NC) is the phenomenon by which two or more negative elements yield just one semantic negation. Sentence (1) is an example from Turkish, in which negative quantifiers obligatorily engage in NC with a sentential negation marker.Footnote 1

-

(1)

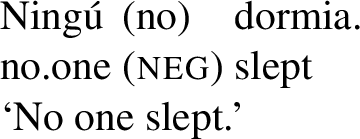

NC phenomena come in various flavors. In the large literature on NC (Labov 1972; Haegeman and Zanuttini 1991; Ladusaw 1992; Acquaviva 1996; Haegeman and Zanuttini 1996; Giannakidou 1997, 2000; De Swart and Sag 2002; Zeijlstra 2004, 2012; Collins and Postal 2014; Collins et al. 2017; a.o.), we find well-represented types such as “strict NC” (negative elements obligatorily cooccur with sentential negation, e.g. in Russian), “non-strict NC” (post-verbal negative elements obligatorily co-occur with sentential negation, e.g. in Spanish) and “negative spread” (two negative quantifiers are interpreted as one sentential negation, e.g. in French). However, more rare or local NC phenomena like “optional NC” (Espinal et al. 2016 for Catalan) and “hybrid NC” (Surányi 2006; Szabolcsi 2018b for Hungarian) are sparsely discussed and more work is needed to see how they fit into the typology of NC systems. This paper addresses this need, by providing an account of optional NC with ne...ne (‘neither...nor’) coordinations in Turkish, a language that otherwise displays strict NC with more common negative items like nobody. Sentence (2) exemplifies the target phenomenon, where the ne...ne phrase can interchangeably cooccur with or without sentential negation, to yield the same meaning.

-

(2)

The NC behavior of these ne...ne phrases contrasts with that of other items such as nobody, that display “strict NC,” i.e. obligatorily co-occur with sentential negation, as shown in (1). We thus observe distinct behavior between NC items across the language: this makes the Turkish NC system a “hybrid.”

There are two possible hypotheses for the source of this hybridity. The first is that Turkish negative quantifiers and neither...nor phrases have an inherently different status in the NC system of the language, which results in a different NC behavior. The second is that they have the same status, but that the observed difference is due to an interaction with factors external to the NC system. In this paper, I will argue for the second hypothesis, in a unified, reductionist account for the hybridity and optionality observed in Turkish NC. In this proposal, negative quantifiers and ne...ne phrases have the same status in the NC system, and optional and hybrid NC are intricately related surface phenomena whose source is found outside of the mechanics of Turkish NC, namely in the variability of the semantic type of the Negative Concord Item (NCI).

More specifically, the NCI’s semantic type determines its structural relationship with respect to the available positions for sentential negation, which in turn results in the presence or absence of NC on the surface. NCIs of type 〈〈e,t〉,t〉 are found in verbal argument positions, and are therefore c-commanded by the position of the sentential negation marker in their base position; in these cases, they must engage in NC with it. NCIs of type t contain the position of sentential negation; as a consequence, they must be licensed by a higher covert negation, and NC with an overt sentential negation marker does not occur. Thus, depending on whether they coordinate DPs (of type 〈〈e,t〉,t〉) or TPs (of type t), ne...ne phrases will either be c-commanded by or contain the position of sentential negation marker: only in the former case is sentential negation realized. This accounts for the apparent optionality of NC with ne...ne phrases. Furthermore, negative quantifier NCIs like hiçkimse (‘nobody’) have a typical generalized quantifier type 〈〈e,t〉,t〉, and are therefore c-commanded by the negation marker, licensing its obligatory appearance, and accounting for their well-known strict NC behavior.

These facts are straightforwardly accounted for in a theory of NC as syntactic agreement (Zeijlstra 2004, 2012): NCIs carry uninterpretable negative features [uNeg], and have to be c-commanded within a phase by an element carrying interpretable features [iNeg]. Among [iNeg] carriers, we find the overt sentential negation head, which immediately c-commands the vP, and a covert negative operator, which is merged above the CP. The overt negative marker licenses NCIs originating in the vP, i.e. those of type 〈〈e,t〉,t〉; the covert negation licenses NCIs that are not c-commanded by overt sentential negation—in particular, ne...ne phrases of type t.

In sum, the optional NC observed with ne...ne phrases is triggered by the type flexibility of the coordination operator, while hybrid NC is due to the difference in type between ne...ne phrases and negative generalized quantifiers. This work contributes to understanding of some of the more subtle aspects of the typology of NC, and it offers an analysis that can be checked for other languages and naturally extended to them. Furthermore, this analysis relies on, and therefore provides support for, a theory that allows type flexibility for coordinations, as proposed by Partee and Rooth (1983), Hendriks (1993), Winter (1996), contra obligatory conjunction reduction proposals by Ross (1967), Hankamer (1979), Hirsch (2017), Schein (2017), which make coordinators of propositional type only.

This paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, I present characteristic data points for the hybridity of Turkish NC between strict and optional NC, and give some definitions. In Section 3, I provide empirical evidence for the proposed dependence of the presence of NC on the semantic type of the NCI (propositional vs. not). In Section 4, I formalize the analysis using Zeijlstra’s (2004, 2008) theory of NC. In Section 5, I discuss two alternative analyses for Turkish optional NC with ne...ne phrases: a focus-dependence analysis of as proposed by Şener and İşsever (2003), and a Hungarian-style analysis as proposed by Szabolcsi (2018a,b). In Section 6, I discuss how the proposed analysis may extend to other languages. Finally, in Section 7, I conclude.

2 Turkish negative concord: Hybrid between strict and optional

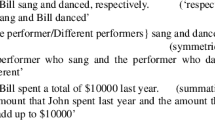

Turkish has been described as a strict NC language (Zeijlstra 2004), because of the obligatory presence of a sentential negation marker, such as the verbal negation suffix -mAFootnote 2 or the copular negation değil, whenever a negative quantifier, e.g. hiçkimse, is present in the sentence, as in (3) and (4). Furthermore, despite the presence of two negative elements, no double negation (DN) reading is available.

-

(3)

-

(4)

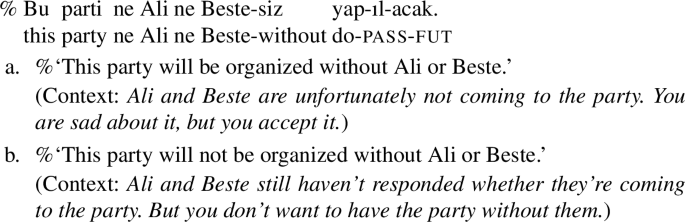

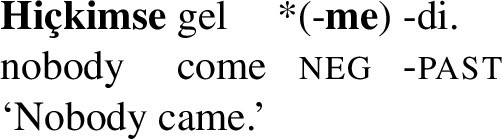

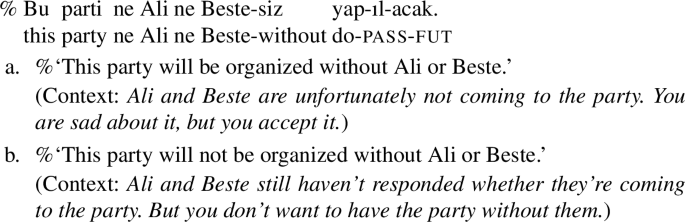

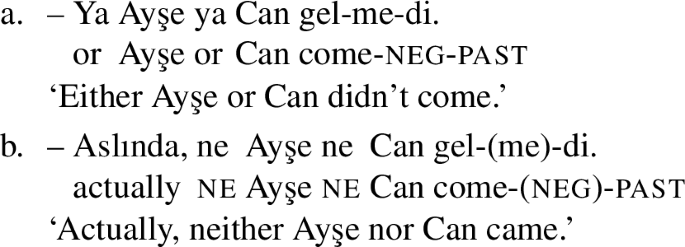

Authors have challenged the descriptive claim that Turkish is a strict NC language (Gencan 1979; Göksel 1987; Şener and İşsever 2003), observing that NC with ne...ne (‘neither...nor’) phrases is optional. In other words, they do not need to co-occur with a sentential negation marker, as shown in (5) and (6). Furthermore, when they do, both a single and a double negation reading are available.

-

(5)

-

(6)

In this paper, I refer to ne...ne sentences “with NC” as those that pattern like (5b-i) and (6b-i)—where the ne...ne phrase co-occurs with a sentential negation marker but only one negation is interpreted; ne...ne sentences “without NC” correspond to those that pattern like (5a) and (6a)—without sentential negation, or (5b-ii) and (6b-ii)—with a sentential negation and a double negation reading, i.e. sentences where the ne...ne phrase appears to contribute its own semantic negation.

Speakers claim that truth-conditionally equivalent ne...ne sentences without and with NC can be used interchangeably (i.e. (5a) vs. (5b-i), or (6a) vs. (6b-i)). Nevertheless, ne...ne sentences with NC are reported to sound slightly more marked (though not less grammatical, i.e. they always receive the highest rating on a 5-point scale). The analysis developed in this paper will provide a hypothesis as to the source of this markedness (see Sects. 3.1.6 and 5.1.4).

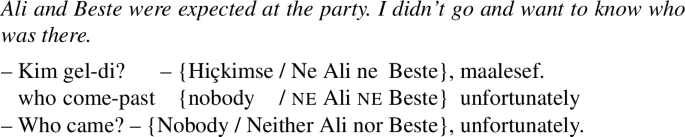

The comparison between ne...ne and hiçkimse is warranted because both fall under the definition of Negative Concord Item (or “n-word”: Laka 1990; Giannakidou 2006; Giannakidou and Zeijlstra 2017; a.o.), that I give below in (7).

-

(7)

Requirement (7a) is satisfied for hiçkimse by data exemplified by (3).Footnote 3 For ne...ne phrases, this requirement is satisfied by the single negation reading of (5b). Requirement (7b), i.e. the ability for hiçkimse and ne...ne phrases to be fragment answers, is also satisfied, as shown in the following.

-

(8)

We can identify two classes of NCIs in Turkish: 1) generalized quantifier NCIs: quantifiers like hiçkimse (‘nobody’), hiçbirşey (‘nothing’), hiçbir zaman (‘never’), for any noun X, hiçbir X (‘no X’), asla (‘never’) (Kelepir 1999; Özyıldız 2017); and 2) coordination NCIs: ne...ne phrases. The first class, those of quantifier NCIs, behave strictly, i.e. like hiçkimse in example (3). I give the definition of strict NC in (9). The second class, the ne...ne phrases, behave optionally, as shown in example (5). The definition of optional NC is given in (10).

-

(9)

-

(10)

In these definitions, strict NC and optional NC are properties of the behavior of NCIs, rather than properties of a grammar, as they are standardly defined in the literature. This shift in definitions reflects the new observation that some languages, like Turkish, are “hybrid,” i.e. have NCIs that do not behave uniformly in how they engage in NC.Footnote 4

In this section, I have shown that two classes of NCIs in Turkish, namely negative quantifiers and ne...ne phrases, have a different NC behavior. In this paper, they will receive a unified analysis in an account of Turkish NC, despite the differences in their surface behaviors. In the next section, I will expose their identical status by showing that the difference in NC behavior does not depend on a particular NCI, but on its semantic type.

3 The dependence of NC on the NCI’s semantic type in Turkish

In this section, I show how the presence of NC depends on the semantic type of the NCIs involved. Section 3.1 shows that the presence of NC depends on the type of the constituents coordinated by the ne...ne phrase. Section 3.2 generalizes this result to all NCIs in Turkish.

3.1 Optional NC with Turkish ne...ne phrases

I propose a novel descriptive analysis for the optionality of NC with Turkish ne...ne phrases, as strictly depending on the flexibility of the semantic type of the constituents coordinated by ne...ne. This flexibility allows for coordinations of different sizes, for example TP coordination, when ne...ne coordinates tensed propositions, or DP coordination, when ne...ne coordinates generalized quantifiers. As a result, the ne...ne coordination operator will have a different syntactic relationship with respect to a clausemate sentential negation, found in Turkish between T and v (as shown by the order of morphemes in the verbal complex v-Neg-T). Either the position of negation is contained in the coordination, in cases of tensed propositions, or it is able to outscope it, in cases of DP coordination, and a variety of other cases. I propose that this relationship determines whether the ne operator and sentential negation engage in NC with each other: when the position of negation is contained in the ne...ne coordination, NC is not possible, but when it is outside of it, it is obligatory.

This established, we can reduce the apparent optionality of NC with ne...ne phrases to the actual optionality of underlying structures for a given string containing a coordination. It is standardly assumed that a coordination structure whose surface form is of the type ne XPne XPVP is structurally ambiguous between a coordination of XPs and full clausal [XP VP] coordination with elided (or raised out) material. Therefore, the potential space of possibilities for such a structure, given a ne...ne sentence without and with NC with sentential negation, includes the options in (11).

-

(11)

However, I propose that because of additional constraints imposed by the NC system, not all these possibilities are available for Turkish ne...ne phrases, and that only two of the four are possible, in the way shown in (12).

-

(12)

Note that there is another possible structure for the string with negation, namely: [Ne [XP<VP>] ne [XPVP]]-neg. Whenever such a configuration is possible, NC is obligatory, as a case where negation outscopes the coordination. However, due to Turkish-specific morphological restrictions, this structure is rarely observed (as we will see in Section 3.1.1, where I discuss what kinds of constituents in Turkish can be coordinated by ne...ne). In particular, whenever tense is expressed on the verbal complex, this possibility will not be available, and therefore negation will always be contained in the coordination.

I argue for the generalization in (12) by providing evidence that cases of unambiguous tensed clause ne...ne coordination (which always contain sentential negation) are only grammatical without NC (Sect. 3.1.2), and cases of unambiguous DP ne...ne coordination (which never contain sentential negation) are only grammatical with NC (Sect. 3.1.3). In Sect. 3.1.4, I provide an argument from semantic scope: ne...ne outscopes elements in the verbal complex in sentences without NC, as it should if it is clausal coordination, but not in sentences with NC. Finally, in Sect. 3.1.5, I present an additional argument from prosody: I argue that prosodic structure in Turkish coordinations reflects underlying syntactic structure, and the prosody associated with clausal coordination is only available without NC, and the one associated with XP coordination is only available with it. In Sect. 3.1.6 I conclude, and discuss an implication of the analysis.

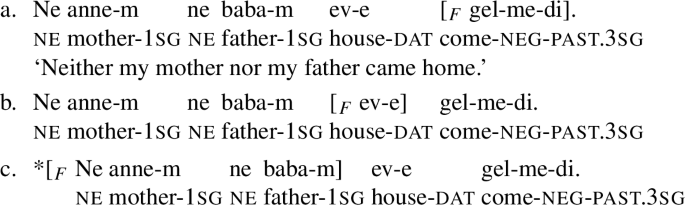

3.1.1 What can and *(can)not be coordinated in Turkish

Coordinations generally can overtly coordinate pairs of phrases of virtually any semantic type. However, the syntax of Turkish imposes some restrictions on what syntactic phrases can be coordinated, notably with verbal complexes, which I discuss in this section, and will become particularly relevant in the discussion in the following section, Sect. 3.1.2.

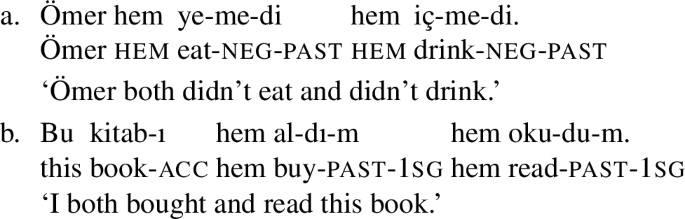

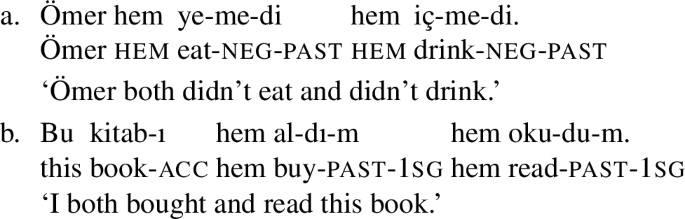

The agglutinative nature of the Turkish verb raises the question as to what is allowed to be coordinated within a verbal complex. In particular, proper subparts of a verbal complex generally cannot be coordinated, where no bound verbal suffix may be left outside the coordination.Footnote 5 Such ungrammatical examples are shown in (13a), (13b) and (14a); grammatical counterparts contain fully inflected verbal complexes, as in (13c) and (14b). I give examples with hem...hem (‘both...and’), but these are replicable with any other type of Turkish coordination, including ne...ne.

-

(13)

-

(14)

In cases shown above, tense and inflection are present, which means that the TP is part of the coordination. Based on this observation, I assume that deficient verbal complexes remain ungrammatical when elided. This means that a case of overt DP coordination, hem Ali hem Beste yemedi (‘both Ali and Beste didn’t eat’) cannot be associated with a structure with a bare vP coordination as in (15a); instead only DP or TP coordination structures (15b–c) are available for that string.

-

(15)

This restriction ensures that coordinations containing the verb also contain the highest projection expressed on the verbal complex.

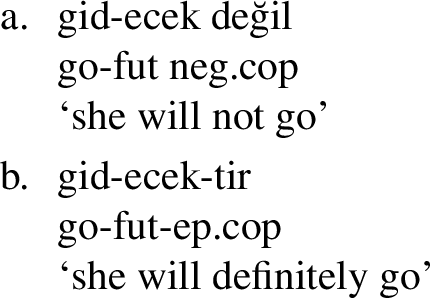

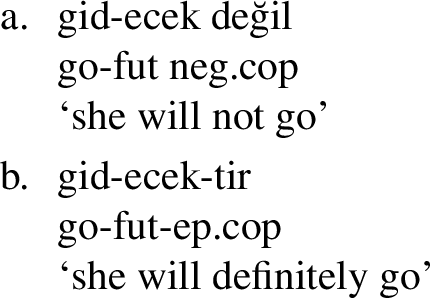

There is a notable (apparent) exception to the ban on splitting verbal complexes in coordinations, which has been discussed by Kornfilt (1996). Bare participial verbs may be coordinated, in which case additional inflectional material can appear outside the coordination. In Turkish, participial verbal complexes include those ending with the progressive marker (-Iyor), future (-(y)AcAK), reported past (-mIş), and aorist (-r), but not past tense -DI. The participial nature of these affixes can be diagnosed by having them be complements to a copula. Below I show the distribution of the participial future suffix -(y)AcAK in (16), that contrasts with that of the past tense suffix -DI in (17). The former can appear with copular forms değil and -DIr, while the latter cannot.

-

(16)

-

(17)

In addition, in contrast with non-participial verbal forms, participial forms such as those marked by -(y)AcAK can be coordinated, leaving additional inflectional material (that is analyzed as attaching to a copula) outside the coordination, as shown in (18).

-

(18)

Therefore, a verbal coordination in Turkish may be outscoped by negation only when it involves a participial form, as in (19), and only with the copular negation değil.

-

(19)

In this paper, I will refer to “tensed verbs” when talking about verbs that are marked by inflectional tense like past tense -DI, but not those marked with participial tenses. Kornfilt refers to these participial forms as “fake tenses,” and analyzes them as introduced by a defective, lower TP (Borsley and Kornfilt 2000). Alternatively, these affixes can be semantically analyzed as aspectual operators, instead of temporal, as argued by Jendraschek (2011) (e.g. the apparent future morpheme -(y)AcAK is in fact the prospective aspect), and can thus simply be introduced by AspP. As a consequence, no coordination of real tensed verbs can be outscoped by a negation marker.

I end with another property of Turkish coordinations: overt coordination of tensed verbs, e.g. (20a–b), always involves underlyingly clausal coordination, even when verbal arguments appear outside of it. When said tensed verbs are negated (as in (20a)), negation can only be interpreted inside the coordination (i.e. the sentence cannot have the reading ‘Ömer didn’t both eat and drink’), which means that it cannot be a simple morphological reflex of a higher null negation outscoping the coordination,Footnote 6 but rather the actual realization of the interpretable head of a negative projection. Arguments of the verb are assumed to be introduced below negation, therefore they must be contained inside the coordination in their base position, from which they undergo ATB extraction to a position outside of it. This is the case for the subject in (20a) and the object in (20b).

-

(20)

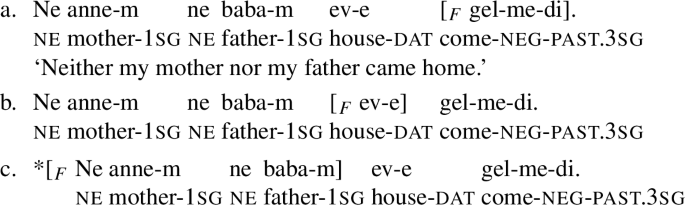

3.1.2 When ne...ne coordinates tensed propositions, there is no NC

In this section, I argue that all cases of ne...ne coordinations of tensed propositions are cases in which there is no NC between the NCI and the negation marker -mA. I do so by looking at various cases of unambiguous propositional coordination, all incompatible with NC: overt coordination of tensed clauses, forward gapping structures, unambiguous backward gapping structures, and tensed verb coordinations. I then argue that the restriction should also apply to underlying propositional coordination when the surface string is ambiguous with a non-propositional structure.

First, simple overt clausal ne...ne coordination is incompatible with NC with sentential negation -mA. In a context that makes the single negation reading available, but not the double negation one, as in (21a), ne...ne can felicitously coordinate non-negated clauses. However, a ne...ne coordination of negated clauses in that same context is infelicitous (indicated by #), which means NC between the ne...ne coordinator and the -mA negation is not observed in this case. The ne...ne coordination of negated clauses is nevertheless grammatical and felicitous in a context that makes the double negation reading available, as in (21b), underlining the possibility of a reading without NC.Footnote 7

-

(21)

Similarly, forward gapping sentences (Hankamer 1971; Kornfilt 2012) are taken to be clausal coordination structures that elide part of the material in the second coordinand. And indeed, in forward gapping structures, like (22), NC is again unavailable.

-

(22)

In (22) and henceforth, I omit the contexts which differentiate single and double negation readings, but these can be reconstructed in the following way: a single negation reading of a ne...ne sentence (i.e. of the form ne A ne B, or the intended NC reading of ne A-neg ne B-neg) is associated with an expectation that A and B might occur (e.g. that Deniz dance and Tunç dance for (22a) and (22b-i)); a double negation reading of a sentence of the form ne A-neg ne B-neg is associated with an expectation that not A and not B might occur (e.g. that Deniz not dance and Tunç not dance for (22b-ii)).

Coordination of tensed verbal complexes is also incompatible with NC. As discussed in Sect. 3.1.1, these are also cases of TP coordination.

-

(23)

So far, we have looked at cases with overt clausal coordination, without and with ellipsis in the second coordinand, and coordination of tensed verbs. These are all unambiguous cases of clausal coordination, and all are incompatible with NC between ne...ne and -mA. However, the main claim regarding Turkish optional NC involves strings of the type ne XPne XPVP(-neg), which are in principle, as mentioned earlier, structurally ambiguous between an XP coordination and a full clausal coordination with “backward gapping,” i.e. missing material from the first coordinand (which has been elided or raised out). The argument made that clausal coordination is incompatible with NC should then extend to cases of underlying TP coordination with backward gapping.

We can find support for this move by building unambiguous backward gapping cases, where a subject-object string is what is overtly coordinated, as in (24) and (25). The smallest constituent that contains both the subject and the object is a complete verbal phrase—therefore the verb must be part of the coordination in the base structure. Indeed, Ross (1970) argues that such structures force the presence of verbal ellipsis, while Hankamer (1979) argues that in verb-final languages, like Turkish, backward gapping cases could be instances of Right Node Raising (see also Kornfilt 2012, 2019 for a similar proposal for backward gapping as RNR). I remain neutral about which analysis is correct since both require vP coordination (and therefore clausal, following the argument in Sect. 3.1.1), and that is what is important for our purposes. And indeed, we see that gapping structures in ne...ne phrases are incompatible with NC, as shown in (24) and (25). This therefore provides yet another example in which clausal coordination is incompatible with NC.

-

(24)

-

(25)

In this section, I have given examples of a variety of unambiguous cases of tensed propositional ne...ne coordination, all of them being incompatible with NC with the sentential negation morpheme -mA. This suggests that all cases of propositional ne...ne coordination are impossible with NC, including those whose surface realizations would in principle be ambiguous with DP coordination, like those in (26).

-

(26)

Interestingly, the claim that there is no NC with clausal coordination only holds for bound morpheme -mA. For some speakers (but not all), clausal coordination with copular değil instead seems to yield NC, and does not have a double negation reading.

-

(27)

For these reasons, I formulate the generalization only in terms of sentential negation bound morpheme -mA, and I leave the analysis of değil for further work.

In the next section, I will argue for the converse of this claim, namely that all cases of non-propositional ne...ne coordination have obligatory NC with -mA.

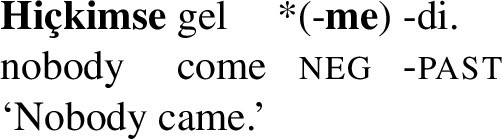

3.1.3 When ne...ne coordinates non-propositional elements, there is NC

In order to argue that cases of non-clausal coordination have obligatory NC with sentential negation, I will concentrate on unambiguous cases of DP coordination, and show NC with sentential negation is obligatory. Unambiguous cases of DP coordinations will be built in two different ways: by “backgrounding” them (by rightward movement), and targeting them with focus-sensitive operators.

Backgrounding

Constituents can be “backgrounded” by being placed post-verbally. I assume the analysis proposed in Kural (1992, 1997); Kornfilt (2005); in which the constituents are generated in a verb-final clause, and moved rightward, adjoining to the entire structure.

Backgrounding ne...ne phrases is possible, but only when the sentential negation marker is present. Moreover, in such cases, the only possible reading is one with NC, i.e. there is no double negation reading (in contrast with corresponding non-backgrounded ne...ne sentences such as (5b)).

-

(28)

This contrast suggests that the ne...ne phrase is a constituent in the NC sentence (28a), but not in the non-NC sentence (28b), which could be reflective of the ne...ne phrase in (28a) being a coordination of DPs, and in (28b) a coordination of TPs, where the verb is elided in its first constituent. This data therefore provides support for the proposal in which DP-sized ne...ne phrases must engage in NC with sentential negation, while TP-sized ne...ne sentences cannot.

Note that this point entails that backward gapping with clausal ne...ne phrases is only possible if there is ellipsis of the verb in the first coordinand (Ross 1970), but not RNR (Hankamer 1979; Kornfilt 2012, 2019). If the verb had undergone RNR in (28b), then ne Ali ne Beste would be a constituent (with traces of the verb in both coordinands), and could therefore undergo backgrounding. However, since the resulting string is ungrammatical, this operation is likely to be unavailable, if there are no further restrictions on backgrounding RNR-ed constituents.Footnote 8

While this rightward movement works as a constituency test, leftward movements from scrambling, or pseudo-clefting, are not reliable constituency tests for coordination structures in Turkish, because they are compatible with ellipsis, as I show below. Sentence (29a) shows a fronted object ne...ne phrase. While this can be a case of an object ne...ne phrase that moves above the subject, it can also be analyzed as clausal coordination, in which each object DP moved clause internally, i.e. inside each coordinand. The subject and verb, being non-contrastive, are then elided in the first coordinand. We can check that such a structure is indeed possible by keeping the material overt in the first coordinand, as in (29b).Footnote 9

-

(29)

Focus-sensitive operators

For some speakers, ne...ne phrases can be targeted by focus-sensitive operators such as only and even. When they are, there must be NC.

The following minimal pair reveals the effect of the presence of sadece (‘only’) applied to the ne...ne phrase.

-

(30)

Turkish sadece associates with a focused constituent to its immediate right. In particular, in sentence (30b), sadece is targeting the ne...ne DP phrase (and not the whole sentence, since the object is extracted out of it). Therefore, the ne...ne phrase must be a constituent. And in this case, negation -mA must appear on the verb, in contrast with (30a).

Another example in the same vein involves the focus-sensitive particle bile ‘even.’ In Turkish, bile attaches directly to the right of the targeted constituent. Therefore, for the string ne Ali ne Beste bile gel(me)di, there are two attachment possibilities: either it attaches to the whole ne...ne phrase, or to the second member only (Beste). The resulting meanings are different. In the first case, the sentence presupposes that it was unlikely that neither Ali nor Beste would come, i.e. it was likely that at least one would come, where Ali and Beste have equal likelihood of coming. In the second case, the sentence presupposes that it was unlikely that Beste wouldn’t come, i.e. it was more likely that she would come than available alternatives, namely Ali. I presented contexts which made one presupposition available but not the other, and tested the felicity of the presence and absence of NC. Below are the results.

-

(31)

-

(32)

The first context is the one in which bile attaches to the whole ne...ne phrase, which therefore must be a constituent on its own. The sentential negation marker is obligatory, corroborating the claim that NC is obligatory with non-clausal ne...ne phrases. The second context is the one in which bile attaches to Beste only, therefore leaving the syntax of the ne...ne phrase ambiguous between DP or clausal coordination. In this case, the sentential negation marker is optional, thus correlating with the ambiguous constituency of the coordination.

In this section, I have given evidence that whenever the ne...ne phrase is forced to be a DP coordination, i.e. when it is backgrounded (moved rightward) or targeted by a focus-sensitive operator, there is NC with sentential negation. Note that these two tests contrast in the information-structural status of the ne...ne phrase: when it is backgrounded, it is given, while when it is targeted by a focus-sensitive operator, it is focussed. These facts go against an alternative proposal for the optionality of NC with ne...ne phrases as having some dependence on focus, proposed by Şener and İşsever (2003). A more complete argument against this proposal is given in Sect. 5.1.

3.1.4 An argument from semantic scope

The proposal that ne...ne with and without NC depends on the size of the coordination predicts different facts about the scope of ne...ne with respect to operators in the verbal complex.

If ne...ne coordinates clauses, it contains the verbal complex, and therefore its negation should scope above anything in it. This prediction is borne out. I use the possibility modal morpheme -AbIl, for its clear scope-taking properties, and its ability to scope above and below negation following morpheme order in regular negated sentences (when it takes scope below, it is realized as -A), as shown in (33).

-

(33)

However, when this modal occurs with a ne...ne phrase without NC, it unambiguously scopes below. This is shown below in (34), for subject and object ne...ne phrases.

-

(34)

This data is strongly suggestive of an obligatory clausal coordination structure. If ne...ne could be a non-clausal coordination in this example, we would expect it to be able to scope below the modal, just like other similar non-ne...ne coordination structures. I show that indeed, ya...ya disjunctions, which are taken to be ambiguous between clausal and non-clausal, can scope above and below the modal. A disjunction under a modal is predicted to have a free choice inference, while a disjunction scoping above a modal has an ignorance inference. Both readings are attested.

-

(35)

Now, turning to ne...ne phrases with NC, the proposal that they are non-clausal predicts potentially different scopes with respect to the verbal complex, with the additional effect of agreeing with a sentential negation marker. In general, the presence of a sentential negation fixes the scope of negation and the modal according to the morpheme order, just like in the basic examples in (33), but also in examples with quantifier NCIs like in (36).

-

(36)

We observe the same pattern with ne...ne phrases with NC, where the scope of negation and the modal is similarly determined by the morpheme order.

-

(37)

To conclude, the clausal/non-clausal analysis of ne...ne sentences without and with NC correctly predicts scope with respect to a modal in the verbal complex: when there is no NC, only clausal coordination, and therefore wide scope of negation with respect to the modal, is predicted to be available, which is what we observe; when there is NC, scope is predicted to be the same as when there is NC with a quantifier NCI, i.e. it is determined by the order of the sentential negation marker with respect to the modal morpheme, which is also what we observe.

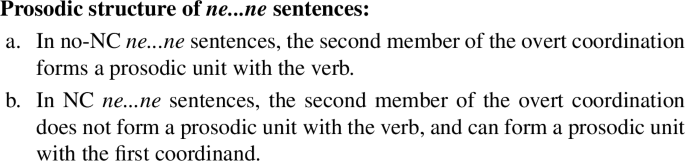

3.1.5 Prosodic structure of ne...ne sentences with and without NC

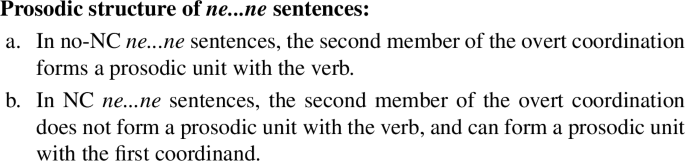

In this section I show that the prosodic structure associated with ne...ne sentences provides additional support for the correlation between NC and the clausality of the ne...ne phrase. In particular, I show that sentences with and without NC have a different prosody, and then I argue that this different prosody underlies different syntactic constituency structures, namely clausal vs. non-clausal coordinations.

I first summarize the main data points that were collected on the prosody of ne...ne phrases in (38) and (39). Brackets indicate relevant prosodic units.

-

(38)

-

(39)

The data in this section was obtained in several ways. The first is through direct observation of sentences produced by native speakers, where prosody between NC and no-NC ne...ne sentences is noticeably different. The second is through collection of grammaticality judgments and corresponding interpretations of ne...ne sentences with prosodic breaks inserted at various points, with hypotheses based on initial observed differences between the two types of ne...ne sentences. These introspective judgments were also checked in recordings obtained from two naive native speakers who were asked to read the relevant sentences and asked to comment on their interpretation. The recordings were imported into Praat and annotated following the intonational phonology system developed in Ipek (2015). In particular, the relevant phrases to be annotated were Ipek’s “intermediate phrases,” i.e. prosodic units bigger than a prosodic word, but smaller than the intonational unit formed by the entire sentence.Footnote 10 Right edges of intermediate phrases are marked by a high tone (H- or LH-), and sometimes a prosodic break.Footnote 11

We observe that the intermediate phrase boundaries differ between ne...ne sentences with and without NC. In particular, as shown in (38), in ne...ne sentences without NC, the first coordinand forms a prosodic unit, marked by a boundary tone at its right edge, and the rest of the sentence, i.e. the second (overt) coordinand and the remaining phonological material form another prosodic unit. In contrast, ne...ne sentences with NC, shown in (39), are characterized by a strong boundary tone and prosodic break at the edge of the overt coordination, and optionally, a boundary tone after the first coordinand, as in (39b) (reported by one speaker to be more marked).

These prosodic structures robustly correspond to no-NC and NC ne...ne sentences. Mixing them up is not possible: if the prosodic structures specific to NC sentences are applied to strings without sentential negation, as shown in (40), the utterances are judged to be bad. Conversely, if the prosody specific to no-NC sentences is used in a ne...ne sentence with sentential negation, as represented in (41), only the double negation reading, not the NC reading, is available.

-

(40)

-

(41)

This final data point in (41) is particularly revealing, because it removes the confound that the presence of the sentential negation marker alone affects the prosody of the ne...ne sentence (an effect that is nevertheless present from -mA being a pre-stressing suffix, as discussed in a later section, 5.1.3). Instead, it becomes clear that the prosodic structure correlates with the presence or absence of NC, whether the verb be negated or not.

The prosodic data and associated NC facts can be summarized as follows.

-

(42)

I argue that this prosodic generalization underlies the syntactic constituency structure of these sentences. In fact, Ipek (2015), in her study of intermediate prosodic phrases, makes the generalization that these phrases correspond to certain syntactic constituents. More broadly, the correspondence between prosodic and syntactic constituency can be captured by Selkirk’s (2011) constraint Prosody-to-Syntax Match (in an Optimality Theory framework; Prince and Smolensky 1993), that states that “the left and right edges of a prosodic constituent must correspond to the left and right edges of a syntactic constituent.” Given the assumption that prosodic units correspond to syntactic ones in these configurations, we can see that the set of prosodic facts summarized in (42) provides direct support for the proposed generalization in (12). Indeed, if the second member of the ne...ne phrase forms a prosodic constituent with the verb, then it forms a syntactic constituent, which corresponds to a clause, and therefore the entire coordination must be clausal.Footnote 12 When the second coordinand forms a prosodic unit with the first, then the entire overt ne...ne phrase is a syntactic constituent, which is incompatible with clausal coordination.

In what follows, I give additional evidence that prosodic units correspond to clausal or non-clausal syntactic constituents in the case of coordination structures. I do so by checking the prosodic facts in non-ne...ne coordinations, against a reliable test for clausal coordination: coordinations of subject-object strings, which must be a result of backward gapping. In simple disjunction cases, both clausal and non-clausal coordination are presumed to be possible, and therefore different prosodic structures are predicted to be available. And indeed, all three prosodic structures, corresponding to constituent and clausal coordination, can be used, as shown in (43). The following data was collected from consultants’ introspective judgments only.

-

(43)

On the other hand, in subject-object coordinations, the prosodic structure associated with clausal coordination is much preferred, as shown in (44).Footnote 13

-

(44)

This result with ya...ya phrases provides support for the claim that prosodic constituency encodes the (non-)clausal nature of Turkish coordinations. In conclusion, the differences in prosody of ne...ne phrases with and those without NC supply additional evidence for the correlation of the presence of NC and the non-clausality of the ne...ne coordination.

3.1.6 Interim conclusion

In this section, I argued for the proposal that states that the absence of NC in ne...ne sentences strictly correlates with coordination of tensed clauses, and the presence of NC in ne...ne sentences with that of non-clausal constituents. I gave evidence from different configurations forcing clausal coordination, namely overt coordination of clauses, verbal complexes, and unambiguous forward and backward gapping structures, and from configurations forcing non-clausal coordinations, namely backgrounding and targeting by focus-sensitive operators. I also gave an argument from semantic scope, based on the fact that a clausal coordinator must scope above elements in a verbal complex, but a non-clausal coordinator may scope in different positions. Finally, I argue that the different prosodic structure of ne...ne phrases without and with NC is revealing of their underlying constituency structure. This allows us to conclude that whenever there is apparent optional NC (as in (2)), it can in fact be reduced to a structural ambiguity: when there is no NC, coordination is clausal, and when there is NC, coordination is non-clausal.

This proposal contrasts with an alternative proposal for the optionality of NC with ne...ne phrases as dependent on focus, as argued by Şener and İşsever (2003). See Sect. 5.1 for my arguments against this proposal.

The analysis presented in this paper crucially relies on the availability of the type-flexibility of coordinators. It is thus incompatible with conjunction reduction analyses, i.e. accounts of coordination that argue for obligatorily clausal coordination (Hirsch 2017; Schein 2017).Footnote 14 In other words, it must assume operators that can coordinate objects of different types, a view defended by Winter (1996); Mitrović and Sauerland (2014); a.o. Nevertheless, as mentioned in Sect. 2, speakers report that sentences with NC in ne...ne phrases are slightly more marked: does this indicate a general preference for clausal coordination? This is plausible from the perspective of the complexity of the semantic type, where coordination of constituents of type t is simpler than for other semantic types, that are argued to be derived by silent type-shifting, as in Winter (1996). This would mean that while conjunction reduction wouldn’t be obligatory, it would still be preferred.

3.2 Hybridity in Turkish NC

In the previous section, I provided evidence for a generalization about the distribution of NC with a certain type of NCI—ne...ne phrases. It turns out we can extend the generalization to all NCIs. In particular, quantifier NCIs, as is well-known and claimed in Sect. 2, always appear with NC in Turkish. Moreover, as generalized quantifiers, they never have a propositional semantic type. We can synthesize the distribution of NC with -mA with all Turkish NCIs in Table 1 above.

This distribution reveals a general dependence of the presence of NC on the NCI’s semantic type, and we can naturally extend the generalization about ne...ne phrases to all Turkish NCIs:

-

(45)

This distribution correlates with the relative position of the NCI and sentential negation, that is assumed to be merged above the vP, as suggested by the morpheme order. Non-propositional NCIs generally correspond to arguments of the verbs (that originate in the vP).Footnote 15 In contrast, when the NCI is propositional, its scope contains the NegP position and thus cannot be licensed by it. These facts will be crucial in the formal analysis for the surface presence or absence of NC, that I give in the next section, Sect. 4.

This generalization stated in terms of semantic type is the crux of the paper. It reveals that ne...ne phrases and quantifier NCIs can be unified in their behavior by appealing to their semantic type. The apparent optionality of NC with ne...ne phrases is a side-effect of the type-flexibility of coordination operators, together with the possibility of ellipsis, that allows a string with apparent DP coordination to be ambiguous between underlying DP coordination and clausal coordination. The hybridity in the Turkish NC system, i.e. the difference in NC behavior is due to the difference in the semantic types between quantifier NCIs and ne...ne phrases: while the latter may be of either propositional or non-propositional type, the former may only be of a non-propositional, generalized quantifier type.

4 Formal analysis

This section provides a formal analysis that accounts for the descriptive proposal presented in the previous section, in which the presence of NC with sentential negation depends on the semantic type of the NCI. In Sect. 4.1, I present the analysis in a nutshell. In Sect. 4.2, I give evidence for a disjunctive and existential semantics for ne...ne and generalized quantifier NCIs, that make it compatible with an agreement-based theory of NC (Zeijlstra 2004, 2012). In Sect. 4.3, I lay out my assumptions about the syntax of the various elements at play. In Sect. 4.4, I give explicit derivations for the basic set of facts that we set out to explain, i.e. the optionality and hybridity in Turkish NC. In Sect. 4.5, I check some additional predictions of this analysis, namely how clausal and non-clausal ne...ne phrases interact with the licensing of other NCIs, and how high NCI adverbials are licensed.

4.1 The analysis in a nutshell

I give an analysis for Turkish NC embedded in the prominent framework for NC as syntactic agreement developed by Zeijlstra (2004, 2012). In this approach, NC is a syntactic Agree relation (Chomsky 1995, 2001) between a single interpretable negative feature [iNeg] and one or more uninterpretable negative features [uNeg], using Multiple Agree (Hiraiwa 2001). Negative feature checking is assumed to be upwards and phase-bound: probes bearing [uNeg] search for a c-commanding phasemate goal bearing [iNeg].Footnote 16

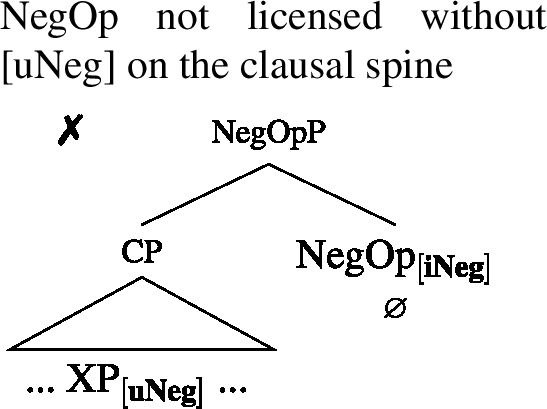

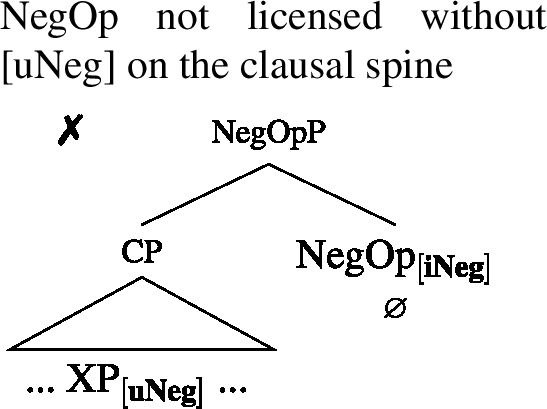

I take Turkish to have the same basic building blocks as non-strict NC languages according to Zeijlstra: NCIs are non-negative indefinites bearing [uNeg], the negation morpheme -mA is a head merged above the vP that carries [iNeg], and in addition, there is a higher null negation NegOp, an [iNeg]-carrying head merged above the CP, whose presence I assume is licensed only if [uNeg] are present on the clausal spine.

NCIs in Turkish include on the one hand typical quantifier NCIs, which I argue are existential quantifiers, and on the other, non-clausal and clausal ne...ne phrases, which I argue are disjunctions. Their [uNeg] features have to be checked off by c-commanding interpretable negative features [iNeg] present within a phase. NCIs originating in the vP—i.e. quantifier NCIs and non-clausal ne...ne phrases—move to spec,vP to get licensed by the Neg head -mA, as shown in (46) and (47). Clausal ne...ne phrases are not c-commanded by Neg and therefore cannot be licensed by it; therefore, they can only agree with NegOp, as shown in (48), whose presence is licensed by the NeP’s [uNeg] being on the clausal spine. Finally, non-clausal NCIs are not on the clausal spine, and therefore, in the absence of other [uNeg] on the clausal spine, cannot be licensed by NegOp (even if they move to spec, CP, i.e. to be in the same phase as the NegOp), as shown in (49).

-

(46)

-

(47)

-

(48)

-

(49)

This analysis thus captures the generalization uncovered in Sect. 3: non-clausal NCIs (i.e. non-clausal ne...ne phrases and quantifier NCIs) always engage in NC with a sentential negation marker, while clausal NCIs (i.e. clausal ne...ne phrases) never do.

4.2 Motivating semantic assumptions: Turkish NCIs are non-negative and existential/disjunctive

In this section, I argue for a non-negative, existential/disjunctive semantics for generalized quantifier NCIs and ne...ne phrases.

There are two equivalent options for the logical form of the NCIs that give the desired meaning. For quantifier NCIs, they are either existentials that scope below a negation (¬>∃) or universals that scope above (∀>¬). For ne...ne phrases, they are either disjunctions scoping below a negation (¬>∨), or conjunctions scoping above (∧>¬). I will argue for both types of NCIs to be existential/disjunctive scoping below a negation. It is important to distinguish between the two possible LFs, because it impacts the relative position of the quantifier/connective with respect to negation, which is crucial to determining the agreement relationship. Furthermore, we can’t rely on cross-linguistic uniformity in choosing the relevant LF: the growing literature on this topic suggests that languages can employ either strategy.Footnote 17

In addition to arguing for an existential/disjunctive semantics for Turkish NCIs, I will argue that they are underlyingly non-negative elements, which provides support for an agreement analysis of NC, where the co-occurring negative semantics is ensured by the NCI’s need to be licensed by a c-commanding semantic negation.

4.2.1 Turkish quantifier NCIs as semantically non-negative existentials

Existential quantifiers

I analyze Turkish quantifier NCIs as underlyingly existential quantifiers, that scope below negation, as opposed to universal quantifiers, that scope above negation. First, existential semantics is suggested by the morphology of NCIs of the type “no NP,” that are realized as hiçbir NP, where the element hiçbir is composed of hiç ‘ever’ and bir ‘one.’ This means that these words are at least historically existential quantifiers. Second, there is evidence in which the scope of the negation and the existential quantifier is split by another quantificational element. I use the well-known observation that negative quantifiers cross-linguistically can be interpreted de dicto (i.e. narrow scope with respect to an intensional operator) in presence of a modal (Jacobs 1980; Geurts 1996; De Swart 2000; Potts 2000; Penka and Zeijlstra 2005; Penka 2011; a.o.), that itself must be interpreted under negation.Footnote 18

-

(50)

-

(51)

The sentences in (50–51) easily have de dicto quantification over things or persons, i.e. under the modal (if it were above the modal, they would only refer to real-world things or persons in a relevant domain). Furthermore, the negation must find itself above the modal verb. Therefore, if the quantifier Q scopes below the modal M, the only scopal configuration of these three elements capable of conveying the relevant reading is the following: ¬>M>Q. Since Q scopes below negation, it must be an existential quantifier, and not a universal.

Non-negative

As noted by Kelepir (1999), Turkish quantifier NCIs never yield double negation readings. We can see this when interacting with sentential negation, whether or not there are several NCIs in the sentence. Moreover, for some speakers, NCIs can be licensed by the suffix -sIz ‘without’ (one of the only configurations where Turkish NCIs appear without sentential negation) that we would expect has a negative semantics of its own; again, no double negation reading is available.

-

(52)

-

(53)

-

(54)

This evidence suggests that NCIs are inherently non-negative, as standard agreement-based analyses of NC generally assume.

4.2.2 Ne...ne phrases as non-negative disjunctions

Disjunctions

I show that ne...ne phrases are disjunctions scoping under negation, by looking at the interaction of ne...ne phrases with the ‘without’ suffix -sIz, that licenses NCIs (as in (54)). Like with sentential negation, there is both an NC and a double negation reading, as shown in the following sentence.

-

(55)

I will use the judgments of speakers who access both readings as a diagnostic for the underlying semantics of ne...ne.Footnote 19

Given the NC reading in (a), the phrase ne Ali ne Beste-siz may have one of the two following equivalent logical representations, depending on whether ne...ne is underlyingly a disjunction or a conjunction:Footnote 20

-

(56)

I argue that the correct logical form for the NC reading of (55) is the disjunctive LF in (56a). Let us consider the conjunctive LF as a possibility. In (56b), without is interpreted twice, once on each conjunct. If this were the correct LF, the underlying syntactic form of (56) must have -sIz twice on each conjunct, with its first occurrence elided. Given that ellipsis is generally optional in coordinate structures, we would expect an overt first occurrence of -sIz to not affect the availability of the NC reading. However, it does: when -sIz appears overtly on each coordinand, the NC reading is not recovered, and only a double negation reading is available, as shown in (57).

-

(57)

This result suggests that the conjunctive LF (56b) does not underlie the NC reading in (55a). Instead, the disjunctive LF (56a) is correct: there is no ellipsis of -sIz; instead, a unique -sIz scopes over the entire ne...ne phrase. Moreover, this disjunctive LF immediately predicts the obligatory double negation reading of (57), that would correspond to not [(without Ali) or (without Beste)]. This LF would also underlie the double negation reading of (55), with ellipsis of the first -sIz.

This result permits a unified analysis of ne...ne phrases and quantifier NCIs, in which they can both scope under negation, allowing Zeijlstra’s agreement theory to apply, as long as ne...ne is indeed non-negative.

Non-negative

I argue that ne...ne phrases are non-negative based on the results of Sect. 3.1.3: in cases where ne...ne phrases are non-clausal, they must engage in NC with sentential negation. If they were negative, we would expect a double negation to be available as well. As for clausal ne...ne phrases, their non-negative nature follows from the assumption that the ne operator is the same in both clausal and non-clausal ne...ne phrases. An alternative analysis would make a distinction between clausal and non-clausal ne...ne phrases, and assume that clausal ones are negative, and non-clausal ones aren’t. This would introduce some complexity in positing two different ne operators, but would reduce it in not having to posit an additional null negation operator in the syntax. While most of the data would be covered with this alternative analysis, it is unclear how pre-ne...ne NCIs (see (73)) could be licensed. Furthermore, several authors have argued for the presence of a null negation operator in various languages, as discussed in Sect. 4.3, so assuming its presence is rather innocuous, while assuming two different ne operators that differ in their negativity would be a dubious move.

Proposal: the ne operator

Based on the results of this section, I propose a ne operator, that is a generalized disjunction, whose lexical entry is found in (58) (adapted from Partee and Rooth 1983; Winter 1996).

-

(58)

As is typically assumed for coordination structures, e type individuals, denoting e.g. proper names, type-shift to a generalized quantifier type 〈〈e,t〉,t〉 when combining with ne, that only composes with t-reducible types.

4.3 Syntactic assumptions

In this section, I lay out the key syntactic assumptions necessary for the analysis: the syntax of the negative operators, the domain of negative feature agreement and its consequences, and the syntax of NCIs.

4.3.1 The syntax of Turkish negations

I assume two syntactic positions for semantic negation operators. Both are heads and carry interpretable negative features [iNeg]. The first is the head of the NegP, uncontroversially merged above the vP, as the morpheme order suggests, and realized as the morpheme -mA. Another, that I call NegOp, is merged in a projection above the CP, and is null. The null NegOp is licensed only if there is a [uNeg] on the clausal spine.

The head status of the overt Turkish negation marker -mA is apparent from its fixed position in the sequence of suffixes present on the verbal complex. It can be further diagnosed by showing it does not pass the “why not” testFootnote 21 (used by Zeijlstra 2004, who adopts it from Merchant 2001), as shown in (59) (copular and existential negations are verbal, so the test does not apply to them). In addition, neither -mA nor copular and existential negation markers are able to merge with other syntactic categories, e.g. DPs, as shown in (60).

-

(59)

-

(60)

The idea that there are several projections for Turkish negation should not be surprising, as there is evidence from many languages for two or more positions for negation. In particular, many languages appear to have an overt high position for negation (see e.g. Korean (Loewen 2007); Irish (McCloskey 1979); Basque (Laka 1990); a.o.). Furthermore, these two positions for negation proposed here essentially correspond to those proposed by Zeijlstra (2004) for non-strict NC languages: Italian, for example, has its overt sentential negation non that carries [iNeg], that is merged above the vP, and a null negation, that is merged above the TP. Thus, the [uNeg] features of post-verbal NCIs, that are in the c-command domain of non, can be checked off by its [iNeg] features, while pre-verbal NCIs, that, crucially, are not c-commanded by non in their surface position, agree with the null operator, as represented in (61).

-

(61)

There are differences in the surface facts between Turkish and Italian, namely in the licensing of subject NCIs by sentential negation; I detail my assumptions about how Turkish subject NCIs are licensed in the following section.

4.3.2 Licensing domains

Following Kayabaşıand Özgen (2018) for Turkish and a general consensus on agreement domains, I adopt the assumption that negative feature agreement is phase-bound. I assume, as Chomsky (2008) argues and as is widely accepted, that CPs and vPs form phases. This means that only the edges of CPs and vPs are accessible to operations outside of them.

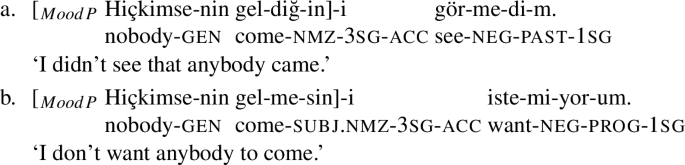

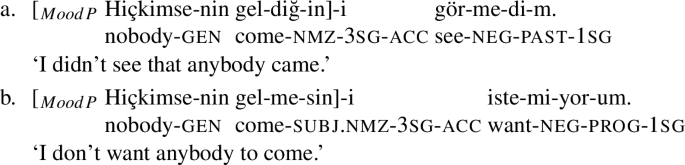

Evidence for negative feature agreement not crossing a CP boundary can be seen in what follows (such data is also discussed by Kornfilt 1984, 1997; Kayabaşıand Özgen 2018). As in many NC languages, agreement of an NCI in an embedded CP by an extra-clausal negation is not possible, as exemplified in (62).

-

(62)

In contrast, (63) has examples in which the NCI hiçkimse in non-tensed clauses is licensed by a matrix negation. Below are examples from indicative (a) and subjunctive (b) nominalized clauses.

-

(63)

It has been argued that Turkish nominalizations contain projections including and below MoodP (Borsley and Kornfilt 2000; Kornfilt and Whitman 2011), but don’t contain the TP.Footnote 22 Thus, they don’t contain the CP layer either. It is thus reasonable to conclude that negative feature agreement is possible as long as the negative dependency doesn’t have to cross a CP boundary.

Evidence for negative feature agreement not crossing a vP boundary is less direct, and I mostly rely on the consensus that it is indeed a phase, and that agreement cannot cross it. However, I take that there is indirect evidence from the absence of scope splitting of negation and the NCI. Since the NegP is merged above the vP, the Neg head that carries [iNeg] may not license any [uNeg] within the vP. I adopt the proposal by Kayabaşıand Özgen (2018) that any NCI base-generated within the vP moves to spec,vP (forming several specifiers in cases of multiple NCIs). If no other projection can come in to host a quantifier in between NegP and vP, there is no space for another DP to come scope in between. This move therefore reflects the empirical generalization that we do not observe the scope of negation and the NCI’s existential operator being split by other quantificational DPs in Turkish, and in NC languages more generally (as observed by St-Amour 2008, and reminiscent of Haegeman and Zanuttini’s 1991 Neg-Criterion, that requires strict locality between negation and NCIs, and Linebarger’s Immediate Scope Constraint for NPI licensing). It also explains why the scope can be split by root modals (as in (50)), whose projection is assumed to be found below sentential negation but above the vP.

Note that this entails that subject NCIs do not move to spec,TP, contra what is standardly assumed for subjects (Kornfilt 1984, 2001; Kural 1993; Aygen 2002; a.o.), but in line with Öztürk (2002, 2005), who argues that subjects in Turkish may but need not raise to spec,TP. We therefore have a system in which NCIs must stay low to satisfy their licensing requirements, and other subjects may move to spec,TP, e.g. to receive a specificity reading. One still might wonder why subject NCIs cannot raise high enough (i.e. spec,CP) to be licensed by the higher NegOp. This is because NegOp is licensed only in presence of [uNeg] on the clausal spine. This assumption can thus serve as an explanation for the difference between Turkish and Italian: the Italian null operator can be licensed without [uNeg] on the clausal spine, while its Turkish counterpart cannot. In Turkish, the only [uNeg]-carrying head on the clausal spine is the head of the NeP in the case of non-embedded ne...ne coordinations, i.e. clausal coordinations (see the following Sect. 4.3.3 for the head status of the [uNeg]-carrying Ne operator). And we will see in Sect. 4.5.1 that only in the presence of a clausal ne...ne phrase, and within reach of the NegOp, i.e. above the ne...ne phrase, can a quantifier NCI be licensed without the sentential negation marker. In consequence, the overt sentential negation marker Neg licenses all NCIs that are base-generated within the vP, which includes all quantifier NCIs and non-clausal ne...ne phrases. The only NCIs not in this domain are clausal ne...ne phrases, i.e. TP/CP coordinations. These NCIs will be licensed by the higher negation operator NegOp.Footnote 23

4.3.3 The internal syntax of NCIs

As argued in Sect. 4.2, both quantifier NCIs and ne...ne phrases are non-negative. I adopt Zeijlstra’s (2004) basic analysis for NCIs in NC languages, i.e. NCIs carry [uNeg] features. I assume that quantifier NCIs are non-negative existentials, formed from an [uNeg]-carrying existential quantifier combining with an NP (following Penka 2011, 2012). I adopt a standard syntax for quantifier phrases, in which the logical operator sits in its head, and the NP is in its complement.

-

(64)

Like quantifier NCIs, ne...ne phrases carry uninterpretable negative features [uNeg]. I assume a standard non-committal syntax of coordination, where the coordinands are in the specifier and argument of a NeP, and the ne operator is in the head of the NeP, carrying [uNeg].

-

(65)

I remain agnostic with respect to the status of the ne particles. They could be inserted post-syntactically as marking the left edge of each disjunct. Alternatively, they could be obligatory markers agreeing with a higher existential operator quantifying over the members of the coordination, as proposed in Den Dikken (2006) and Szabolcsi (2018b); I omit it from this discussion for the sake of simplicity, and because the choice of the analysis does not impact the analysis of ne...ne’s interaction with NC.Footnote 24

4.4 Combining the ingredients and deriving the data

In the following derivations, I assume extensional compositional semantics, ignoring tense. I also assume a head-final structure for the projections on the clausal spine.

4.4.1 Licensing non-clausal NCIs

In this section, I show how non-clausal NCIs, namely non-clausal ne...ne phrases and quantifier NCIs, are licensed.

I derive the licensing of a DP ne...ne coordination in (66). The ne...ne coordination, here acting as a subject, originates in the specifier of the vP, and moves up to spec,vP to get licensed by the Neg head (for simplicity purposes, I ignore the predicate abstraction node).

-

(66)

In an identical way, I derive the licensing of a quantifier NCI in (67), where the quantifier NCI is in the same position as the ne...ne NCI. Again, the [uNeg] of the NCI is checked off by the [iNeg] of the Neg head, after it has undergone movement to spec,vP.

-

(67)

In both (66) and (67), the non-clausal NCI can only be grammatical if sentential negation is present. If it were absent, there would be no [iNeg] to check off the NCI’s [uNeg]. The NegOp, merged above the CP, could not check off the negative features of the NCI (even if it were to move up to spec,CP), because the [uNeg] present in the structure are not on the clausal spine.

In this section, I have shown derivations that reveal the mechanism by which non-clausal ne...ne phrases and quantifier NCIs have a strict NC behavior, i.e. require the presence of a clausemate negation marker.

4.4.2 Licensing clausal NCIs

I show in (68) a derivation in which a clausal NCI is licensed. The ne operator selects for two CPs, and its [uNeg] is checked off by the [iNeg] of the NegOp, merged to the ne...ne coordination. The NegOp is licensed, because the [uNeg] of the NeP are on the clausal spine. Since the NegOp is null, there is no phonological realization of the semantic negation operator in this sentence.

-

(68)

The following derivation shows that sentential negation cannot license a clausal ne...ne phrase, since it does not c-command it. The only way for such a string to be grammatical is if an NegOp is merged to the NeP to check off its uninterpretable features. In this case, there are several semantically negative operators, one licensing the ne...ne phrase, and the other two appearing in each coordinand. This results in a double negation reading, as observed in the data.

-

(69)

4.5 Checking additional predictions

4.5.1 Licensing multiple NCIs

In this section, I discuss some additional data on sentences with multiple NCIs, specifically with a ne...ne phrase and another NCI (ne...ne or quantifier).

Quantifier NCIs are generally ungrammatical in the scope of ne...ne phrases, when a sentential negation marker is absent, as shown in the following examples.

-

(70)

This data is predicted by the analysis proposed in this paper: quantifier NCIs cannot be licensed by NegOp, because the NCIs are separated from the NegOp by a CP boundary, and therefore agreement cannot occur. For agreement to occur, the NCI would have to move to a high enough position to be licensed by NegOp, e.g. spec,CP. However, in (70), this is not possible: the subjects of each coordinated clause would have to move to an even higher position than spec,CP, which is predicted impossible by scope economy, because the subjects are scopally vacuous. For this reason, sentential negation is obligatory in (70a) to make the sentence grammatical (and licenses at once the non-clausal ne...ne phrase and the quantifier NCI). In (70b), sentential negation would make the sentence grammatical, but only with an DN reading, because of the obligatory clausal coordination.

In contrast, in cases in which NCIs themselves are overtly coordinated by ne...ne, the sentence without negation is acceptable (and borderline for some speakers).

-

(71)

This can be explained if the NCIs have moved to spec,CP, a position in which they can agree with NegOp. In this sentence, the subject undergoes ATB movement out of the coordination.

Furthermore, quantifier NCIs are grammatical in front of a ne...ne phrase and without a sentential negation marker (for a majority of speakers). Examples with both subject and object quantifier NCIs are shown below.

-

(72)

In order to explain this data, I assume that NCIs can raise to a position between the NegOpP and the NeP (e.g. by Chomsky adjunction to the NeP, or to a specifier of the NeP), and have their [uNeg] features checked there.

-

(73)

Examples (71–73) display configurations of quantifier NCIs agreeing with NegOp. They are exceptional because NegOp is generally not licensed in the presence of quantifier NCIs, since their [uNeg] are not on the clausal spine. But it is the presence of clausal ne...ne phrases that allows NegOp to be used, which then can license whichever NCI is present in its agreement domain.

Finally, several ne...ne phrases can be licensed at once, as in (74).

-

(74)

The analysis proposed in (73) can then be identically applied to this example, where the first ne...ne phrase is non-clausal, and the second is clausal.

4.5.2 Licensing high NCI adverbials

The analysis proposed has an idiosyncracy: no NCI that is above the NegP and below the CP could be licensed, since there is no clausemate [uNeg]. The NCIs that would be present in that position would be high adverbials, e.g. of frequency or epistemic modality, that are often said to scope above negation in various languages (Potsdam 1998; Cinque 1999; a.o.). However, attempts to construct adverbial phrases such as ‘with no (high) certainty,’ ‘at no high frequency’ with hiçbir (the equivalent of ‘no’) did not yield anything. Therefore, this specific prediction could not be tested.

However, we can show ne...ne adverbial phrases in high positions cannot be licensed by sentential negation. I first show what the scope of an example frequency adverb nadiren ‘rarely’ is, with respect to sentential negation. It appears to have ambiguous scope with respect to negation when appearing in second position, as in (75a), but only high scope sentence-initially, as in (75b).Footnote 25

-

(75)

Adverbs are taken to be interpreted in the position in which they are base-generated: therefore, in (75b), nadiren is base-generated in a position above negation. This predicts that an equivalent NCI adverb could not be licensed by sentential negation in that position. And indeed, this is what we observe: a ne...ne frequency adverbial—ne bazen ne sık sık ‘neither sometimes nor often’ in that position cannot be licensed by sentential negation, because the NC reading is not available in (76b).

-

(76)

I further note that placing the adverb after the subject allows for a negative concord reading (in addition to a double negation reading).Footnote 26

-

(77)

This means that the ne...ne phrase can be licensed by sentential negation in this post-subject position, which allows us to draw a parallel with the possibility for the adverb in (75a) to scope below negation. Therefore, the ability to be licensed by sentential negation correlates with the availability of narrow scope of the adverb with respect to negation. These findings provide support for the proposal in which the relative position of the NCI with respect to sentential negation determines whether there will be NC. Furthermore, they suggest that there are two positions in which frequency adverbs can be base-generated and scope from: one below sentential negation and one above. When NCI adverbials are generated in the higher position, they cannot be licensed by sentential negation, and are presumably licensed by a higher NegOp (which yields a double negation reading in cases where sentential negation does appear). However, since licensing cannot cross a CP boundary, these high ne...ne adverbials, if originating below C, must be instances of clausal coordination, so that the NegOp can license it.

5 Alternative analyses for optional NC with ne...ne phrases

5.1 Dependence of NC on information structure: Şener and İşsever (2003)

In this section, I argue against the generalization put forth by Şener and İşsever (2003) on the dependence of NC with ne...ne phrases on information-structural focus. I first present evidence that shows that the generalization does not hold, at least for all the native speakers who were asked. I finish by discussing in what ways information structure nevertheless does interact with NC with ne...ne phrases, and how the clausality of the coordination structure itself plays a role.

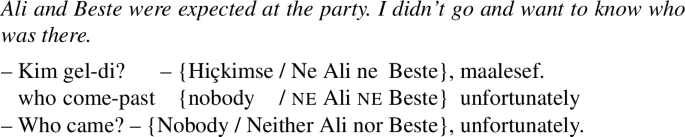

Şener and İşsever (2003) propose an analysis for the optionality of NC with subject and object ne...ne phrases based on their interaction with focus, arguing for a dependency of focal and negative features, where semantic negation is realized only when both of these features are checked. They come up with the following generalization about the distribution of NC in ne...ne phrases (reworded for clarity):

-

(78)

The following sentences, taken from Şener and İşsever (2003), exemplify these conditions. In particular, the ne...ne sentences in (79) lack NC: these can only be grammatical when the focused constituent is the ne...ne phrase. This fact gives rise to the generalization in (78b). The ne...ne sentences in (80) exhibit NC with sentential negation: they can only be grammatical when the focused constituent is different from the ne...ne phrase.Footnote 27 This fact gives rise to the generalization in (78a).

-

(79)

-

(80)

Put against a background of optional NC, this generalization deserves some attention, for the following reasons. First, many authors claim a tight relationship between negation and focus (e.g. Laka 1990; Kural 1992; Pinón 1993). Moreover, as noticed by Zeijlstra (2004) and St-Amour (2009), among others, prosodic emphasis can disambiguate cases of optional NC, as in the following French example.

-

(81)

Despite these cross-linguistic observations that prosodic stress and semantic negation come hand in hand, I will show that Şener and İşsever’s focus-dependency analysis is inadequate to account for the optionality of NC with Turkish ne...ne phrases. In particular, I argue that the generalization in (78) is incorrect, at least for my native-speaker consultants. First, I give a number of arguments against (78a), i.e. that focus on the ne...ne phrase entails the lack of NC (Sect. 5.1.1). Second, I show that (78b), i.e. that lack of focus on the ne...ne phrase entails NC, is true in the cases presented by Şener and İşsever, but not others, and that Şener and İşsever’s cases are explained by this paper’s account, i.e. the presence of non-clausal coordination (Sect. 5.1.2). While I do maintain the possibility that Şener and İşsever and their consultants have a different Turkish grammar from my consultants for the cases that I challenge, I argue in Sect. 5.1.3 that the evidence that they provide to diagnose focus, i.e. prosodic prominence and subtle intuitions about givenness, is insufficient and potentially misinterpreted. Finally, in Sect. 5.1.4, I claim that despite the independence between NC with ne...ne phrases and information structure, there is a non-trivial interaction that often results in effects resembling Şener and İşsever’s generalization, and discuss how these may arise.

5.1.1 Against (78a): Focus on the ne...ne phrase independent of NC

In the following, I argue against (78a), i.e. I show that information-structural focus on ne...ne phrases is not a condition for the absence of NC. I list different tests for information-structural focus in Turkish, and show that all of them allow both focused and non-focused ne...ne phrases to occur with or without sentential negation. I note whenever preferences were observed for one form or the other: however, no systemic correlation between focus and absence of NC was observed across the tests. In all the following examples, the double negation reading is available (with the appropriate context); I ignore it, however, as it is irrelevant to the argument.

1. Question-answer focus

In the following example, the ne...ne sentence is an answer to a wh-question, and is therefore focused. Both forms of the predicate, with and without negation, are possible. In order to control for polarity, the questions were asked both with and without sentential negation.

-

(82)

A note on the judgments: among the seven people asked, most accept all possibilities, but there is some variation, albeit non-systematic, e.g. one person rated the non-negated response for the (i) questions low. This goes in the opposite direction of what Şener and İşsever (2003) expect, i.e. these examples are set up so that the ne...ne phrase is focused. Note that these answers differ from the ones provides by Şener and İşsever for (ii) and (iii).

2. Contrastive/new information focus

Below is a sentence in which the ne...ne phrase is in a contrastive focus position, and also conveys new information, doubly predicting it to be focused. However, both forms of the verb, negated and non-negated, are possible in the ne...ne sentence, with a preference from some speakers for the non-negated version.

-

(83)

3. Corrective focus

Corrective focus is a test that can be used to closely control for the rest of the sentence to stay identical. In the following, what is being corrected is the coordination operator. Again, both forms of the verb are possible.

-

(84)

4. Pseudo-clefts

In pseudo-clefts, the complement of the copula in the main clause is always focused. Here, it is a ne...ne phrase, and it is compatible with both the positive and negative version of the copula.

-

(85)

5. Focus-sensitive operators

As mentioned in Sect. 3.1.3, some speakers allow ne...ne phrases to be targeted by focus-sensitive operators. By definition, this means that the ne...ne phrase is focused. However, in these cases, only the negated form of the verb is possible.

For all five tests, a focused ne...ne phrase is compatible with NC with sentential negation (and for Test 5, has obligatory NC). No native speaker who was asked responded in line with what Şener and İşsever (2003) were expecting, i.e. no NC when the ne...ne phrase is focused. This strongly suggests that information structure does not directly affect the presence or absence of NC with ne...ne phrases, contrary to Şener and İşsever’s claim.

5.1.2 Against (78b): Lack of focus on the ne...ne phrase independent of NC

In this section, I show that the evidence that Şener and İşsever (2003) provide for (78b) is correct, but explainable under this paper’s current proposal. In addition, I present additional cases not considered by Şener and İşsever that falsify (78b).

Şener and İşsever defend their generalization in (78b), i.e. that the absence of focus on the ne...ne phrase entails NC, by presenting examples with focus on constituents clausemate to ne...ne phrases, that are not the ne...ne phrases themselves. Such examples can be found below, in (86) (equivalently, in (79b–c), that contrasts with grammatical NC examples in (80b–c)).

-

(86)

I argue that this fact is in fact a correlate of the absence of clausal coordination. In particular, I show that non-contrastive constituents in the scope of a coordination cannot be focused. Thus, in cases of clausal coordination, only contrastive constituents may be focused. These differ from sentences with non-clausal coordination, in which elements outside of it may be focused.

I first give evidence from a sentence with ya...ya (‘either...or’) coordination of a subject-object string, which must be analyzed as clausal coordination with gapping. Below is a grammatical example, where contrastive elements are focused.

-

(87)