Abstract

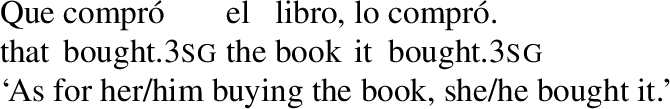

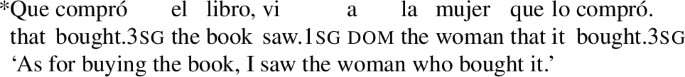

Predicate doubling in Spanish is usually taken to involve multiple copy spell-out. This approach is mainly motivated by the fact that two instances of the same lexical verb appear in the construction, and by the observation that the pattern is sensitive to island restrictions. In contrast, we contend in this paper that predicate doubling is a phenomenon for which an analysis based on multiple copy spell-out cannot be empirically substantiated. We argue that the construction is better understood as involving a base-generated predicate in the left periphery that functions as a contrastive topic. We show that a number of properties of predicate doubling follow from this analysis, including lexical identity between the verbs and sensitivity to islands. Furthermore, our proposal provides a rationale for genus-species splits in the construction, and also offers a straightforward account for otherwise mysterious asymmetries arising with factive verbs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This type of construction has received many names over the years, e.g., predicate cleft, VP-cleft, vP-topicalization, etc. We follow Aboh and Dyakonova (2009) and many others in calling it predicate doubling simply because we find that this terminology describes the phenomenon in a more transparent way.

All Spanish grammaticality judgments reported in this article are provided by the authors and were confirmed by native speaker colleagues. Spanish examples correspond to the Rioplatense variety, in which predicate doubling is a productive pattern.

The landscape of island restrictions in Spanish does not differ significantly from other well-studied Romance languages. There are two topicalization constructions involving leftward dislocation: clitic left dislocation and hanging topics. From these, only the former obeys island restrictions (Zubizarreta 1999; López 2009; Olarrea 2012), the latter being unanimously analyzed as base-generated constituents above the CP level (Cinque 1977; Alexiadou 2006; López 2009); however, see Muñoz Pérez (2021) for the observation that infinitival hanging topics might be island-sensitive. Wh-movement and focus fronting are both subject to canonical island restrictions (Francom 2012; Olarrea 2012).

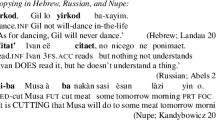

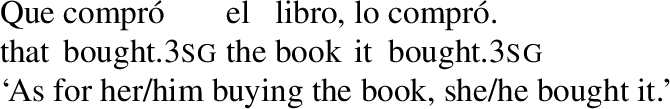

A similar conclusion can be drawn from doubling patterns with finite verbs, which seemingly involve a base-generated CP in the left periphery.

-

(i)

These constructions display island effects just like standard instances of predicate doubling.

-

(ii)

We leave the argument based on these constructions for another time, as the topic deserves separate discussion.

-

(i)

Cable (2004) also arrives at the conclusion that island sensitivity is not a proper argument for movement in predicate doubling, although he does it on different grounds.

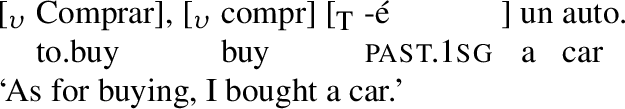

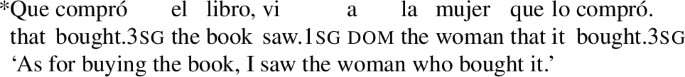

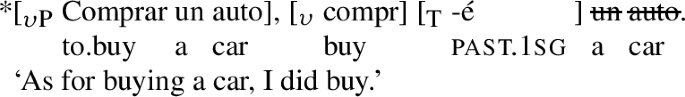

The lack of patterns like (22a) may be taken to follow from Vicente’s (2009) account. He follows Abels (2001) and Landau (2006) in assuming that multiple copy spell-out is a means to save a morphologically deviant structure. In a sentence like (i), the chain C = {υ0, υ0} requires its highest link to be overt. Pronunciation of the lower link is enforced to prevent a violation of the Stranded Affix Filter, since the inflectional morphology of the verb (–e) cannot be spelled-out by itself.

-

(i)

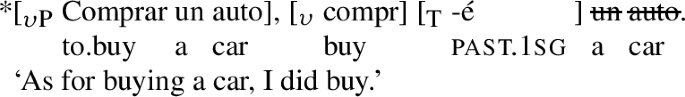

This explanation does not extend straightforwardly to the pattern in (22b), as it predicts that the head υ0 should be the only element within υP that is spelled-out twice. In other words, there is no principled reason for the occurrence of un auto ‘a car’ within the clause to require pronunciation in (ii).

-

(ii)

Even ignoring this technical issue and assuming that Vicente predicts that there are no constructions like (22b) in Spanish, the fact remains that there is no independent motivation for the claim that υ0 or υP undergoes topicalization.

-

(i)

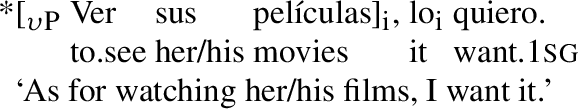

Importantly, note that υPs in Spanish cannot be topicalized via CLLD.

-

(i)

-

(i)

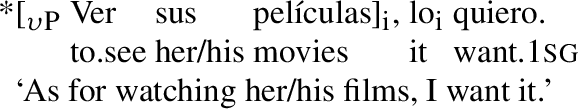

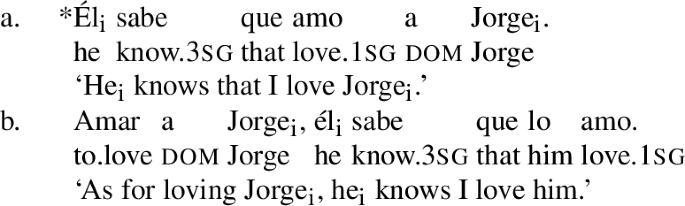

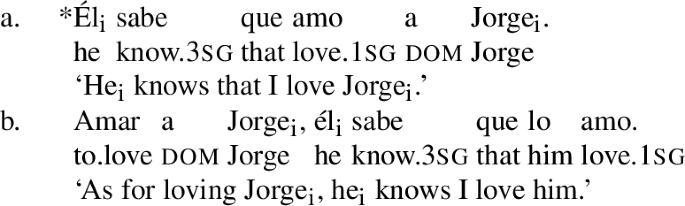

As Martin Salzmann (p.c.) and an anonymous reviewer point out, the reconstruction and base-generation analyses make different predictions regarding Condition C in sentences involving embedding (Takano 1995). According to the reconstruction account, the sentence in (ib) should lead to a Condition C violation, given that the dislocated υP would be interpreted within the clause. As can be seen, this prediction is not borne out. The pattern in (ib) is acceptable, as predicted by the base-generation approach.

-

(i)

-

(i)

According to Vicente (2007), this sentence is acceptable. However, we and our informants find it, at least, deviant. In any case, we find no contrast between this example and the one in (29d), which is taken to involve base-generation.

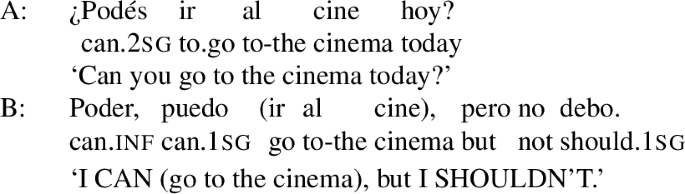

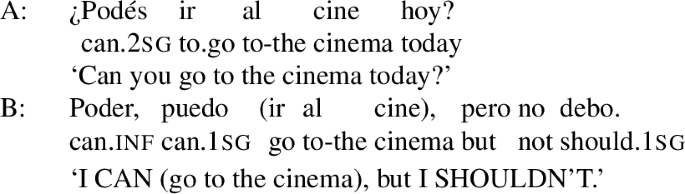

As an anonymous reviewer points out, predicate doubling in Spanish is also acceptable if the doubled predicate is a modal.

-

(i)

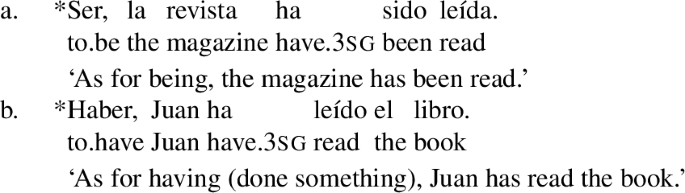

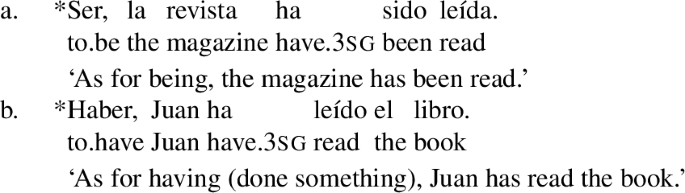

This is expected under the present account. In this example, Predicate 1 signals the presence of alternative questions involving other modal auxiliaries, with which the dislocated verb contrasts, e.g., should I go to the cinema?, must I go to the cinema?, etc. This analysis can also account for the fact that not all auxiliaries can be doubled. As Vicente (2007:63) observes, ser ‘be’ (passives) and haber ‘have’ (perfect tenses) cannot be dislocated in predicate doubling constructions. Given that these verbs lack lexical content, they cannot be used contrastively. In consequence, they cannot function as contrastive topics.

-

(ii)

-

(i)

For the sake of simplicity, we only consider predicate doubling constructions involving bare infinitives and not infinitival phrases. The analysis extends straightforwardly to the latter.

Since these sentences are unacceptable, it becomes difficult to identify where the focus is supposed to be. The location of the F-marking in (62), (65), (68) and (71) is in attempt to comply with the congruence condition and is for expository purposes only. In any case, there is no focus structure that can make these examples congruent.

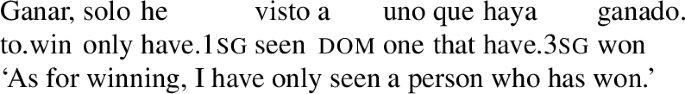

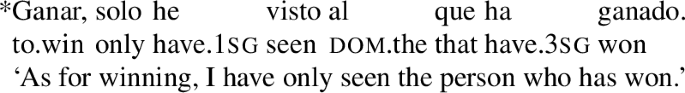

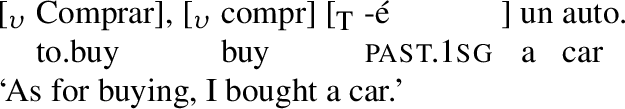

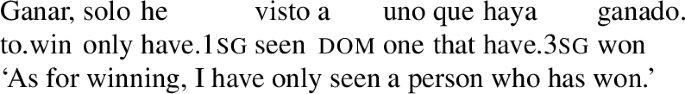

Vicente (2007:80) points out that predicate doubling improves if the DP that contains the relative clause is indefinite. Note that this contrast is unexpected under a movement-based approach.

-

(i)

-

(ii)

A potential explanation in terms of the analysis developed here can be sketched as follows. First, the clause in (i) constitutes an acceptable answer to the QUD did any person win? In this case, the matrix predicate he visto ‘have seen’ seems to receive a parenthetical interpretation (see discussion below), as the embedded clause constitutes the “main point” of the utterance. Thus, the clause does answer a question with ganar ‘to win’ as its main predicate, and thus satisfies the congruence condition. As for (ii), the embedded proposition cannot be taken to answer the QUD did any person win? as the definite determiner already presupposes that someone won. Since the clause in (ii) does not answer a question with ganar ‘to win’ as its main predicate, this predicate doubling sentence is predicted to be ill-formed.

-

(i)

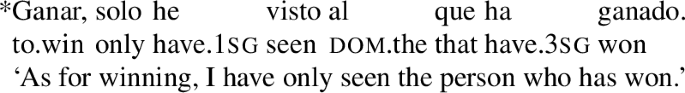

There is a growing consensus that the Coordinate Structure Constraint (CSC) is not a syntactic restriction on movement, but a symmetry requirement that should be understood in semantic terms (Salzmann 2012; de Vries 2017). This approach offers an alternative line of analysis for (70), as the dislocation pattern in this sentence is asymmetric in the relevant sense. Thus, even if our approach is not on the right track, the argument remains that the unacceptability of (70) no longer supports a movement-based analysis of predicate doubling.

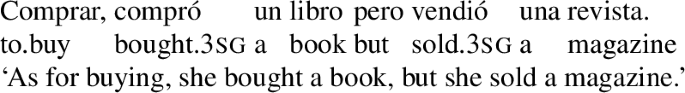

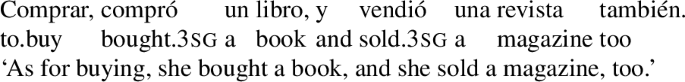

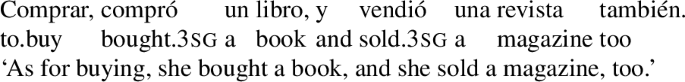

As noticed by an anonymous reviewer, this predicts that the pattern must become acceptable if the contrastive topic is clearly restricted to only one of the assertions. This can be done by replacing the conjunction y ‘and’ for the adversative pero ‘but’ (i) or by introducing some kind of phonological pause between the first coordinate and the second one (ii). As can be seen, the prediction is borne out.

-

(i)

-

(ii)

-

(i)

See also Ambridge and Goldberg (2008) for the claim that islands encode presupposed, i.e., non asserted, information.

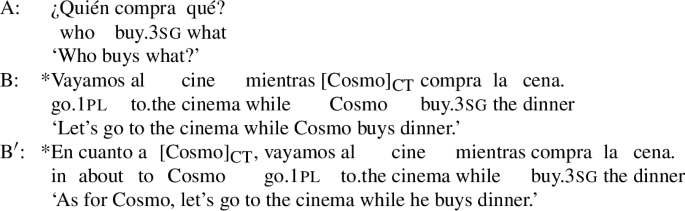

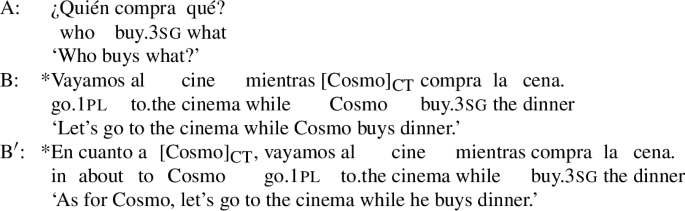

A prediction that arises from this analysis is that nominals within these domains cannot function as constrastive topics either. As the following dialogue shows, this seems to be borne out. The reply in B′ is particularly telling, as the proper noun Cosmo is generated as part of a hanging topic and is only connected through anaphora to the temporal adjunct.

-

(i)

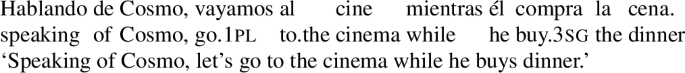

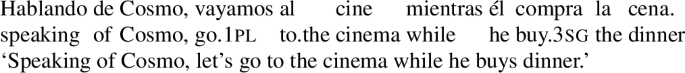

For completeness, notice that a very similar sentence is acceptable if the hanging topic Cosmo is interpreted as a familiar topic (Frascarelli and Hinterhölzl 2007).

-

(ii)

-

(i)

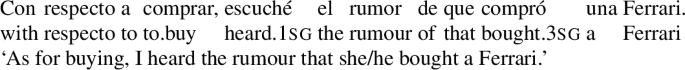

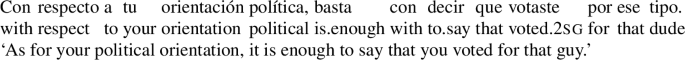

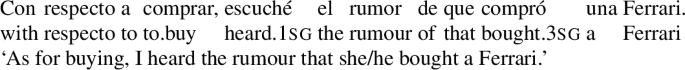

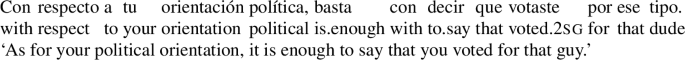

Doubling patterns introduced by prepositional markers such as con respecto a ‘with respect to,’ e.g., (18), are also acceptable if Predicate 2 is within a Complex NP island and the matrix predicate receives a parenthetical interpretation, e.g., (i). This further supports our conclusion in Sect. 2.2 that these constructions do not involve movement.

-

(i)

-

(i)

For instance, complex NPs in Spanish are opaque for wh-extraction no matter whether they are at-issue or not. This suggests that there is a structural restriction at play.

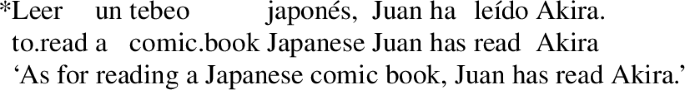

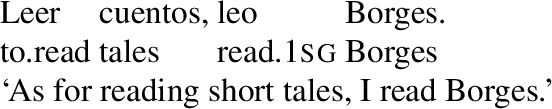

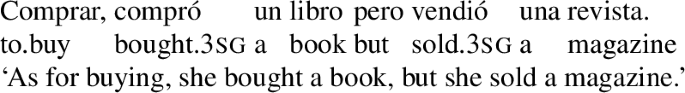

This sort of mismatch is acceptable if Predicate 1 is introduced within a prepositional expression like con respecto a ‘with respect to.’

-

(i)

Con respecto a viajar, Juan ha volado a Amsterdam.

with respect to to.travel Juan has.3sg flown to Amsterdam

‘As for travelling, Juan has flown to Amsterdam.’

In this context, Predicate 1 has a non-contrastive topic interpretation. We conjecture that this follows from prepositional expressions like con respecto a ‘with respect to’ being able to point to a non-immediate QUD. This hypothesis is further supported by the acceptability of sentences like (ii), in which the hanging topic introduces a non-contrastive topic that is merely thematically related to the QUD determining the focus structure of the sentence.

-

(ii)

If our conjecture is on the right track, the unacceptability of the examples in (21) should be explained as the impossibility to accommodate a (non-immediate) QUD relating Predicate 1 and the main assertion within each sentence. For instance, in (21a) there is no question about an event of buying (e.g., what did Eliana buy?) that might be addressed by a question about going to the cinema (e.g., when did Eliana go to the cinema?).

-

(i)

An informal explanation for this effect can be posited in terms of the Manner Maxim (Grice 1975); see Murphy (2003) and Horn (2006) for similar treatments of synonymy avoidance. According to this maxim, utterances should be as transparent as possible. In this sense, one would expect that if a single meaning needs to be expressed twice, a speaker should employ the same form twice rather than using two distinct forms. When the latter happens, an inference arises that both terms have distinct meanings.

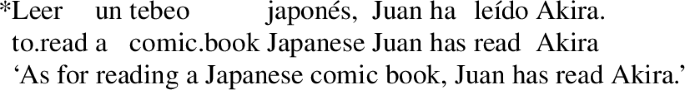

Vicente (2009:170) argues that Spanish predicate doubling does not exhibit genus-species effects. To support this claim, he offers the following example.

-

(i)

We find that this pattern improves significantly if the proper noun is a well-known representative of a certain class, and the nominal within Predicate 1 is a bare noun.

-

(ii)

-

(i)

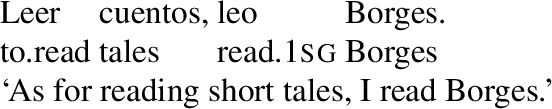

This explains why genus-species splits are attested with nouns only. Bare nouns, both as mass nouns like pescado ‘fish’ in (88a) or as bare plurals like libros ‘books’ in (88b), have been observed to denote kinds (Carlson 1977; Chierchia 1998), a property that other lexical classes, e.g., verbs, simply do not share. Therefore, it is rather unsurprising that a syntactic pattern expressing inclusion relations between kinds is restricted to bare nouns.

These questions can be obtained by applying Büring’s (2003) CT-Value Formation algorithm in (36) to the abstract representation in (92). As a first step, the QUD of this representation would be formed by replacing the focused feature [+C] for the wh-element what. Assuming that the lexical verb is to eat, and that the features [+A][+B] correspond to the noun fish, the resulting question would be equivalent to what fish do you eat? From this question, a set of alternative questions can be formed by replacing the CT-marked segment (i.e., the predicate eat fish) for contextually relevant alternatives.

This is a simplification for expository purposes, as weak islands cannot be reduced to the argument-adjunct distinction. See Szabolcsi and Lohndal (2017) for a complete overview.

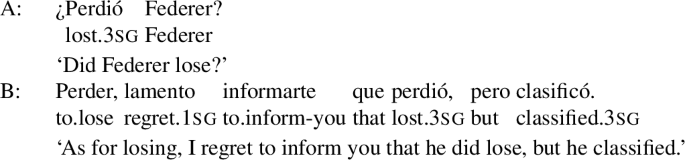

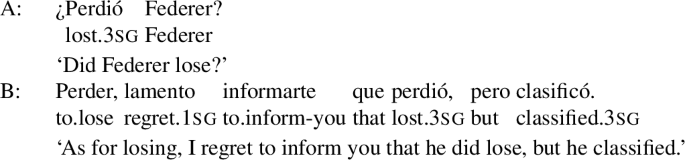

While this is a widely accepted claim, the literature has observed some exceptions. Particularly, it has been noticed that emotive factives can embed announcements in certain contexts. In these uses, the complement clause is not presupposed, but it is taken as new information, i.e., the regret is what is asserted (Abbott 2000).

- (i)

As expected, predicate doubling is acceptable in these contexts (Verdecchia 2021).

-

(ii)

Given that in these cases the embedded clause constitutes the main point of the utterance, the congruence condition for predicate doubling is met (i.e., the sentence can function as an answer for an immediate QUD with Predicate 1 as its main predicate).

-

(iii)

〚Did Federer lose?〛 ⊆ 〚 (...)ΣF Federer did lose〛f

Importantly, it should be noted that these uses of emotive factives trigger mood alternation: they embed an indicative clause rather than a subjunctive one (Real Academia Española y Asociación de Academias de la Lengua 2009:Sect. 25). This explains why the answer in (104) can only be interpreted presuppositionally.

References

Abbott, Barbara. 2000. Presuppositions as nonassertions. Journal of Pragmatics 32(10): 1419–1437.

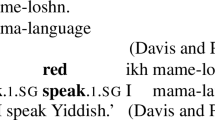

Abels, Klaus. 2001. The predicate cleft construction in Russian. In Proceedings of formal approaches to Slavic linguistics, eds. Steven Franks and Michael Yadroff, Vol. 9, 1–19. Bloomington, IN: Michigan Slavic Publications.

Aboh, Enoch O., and Marina Dyakonova. 2009. Predicate doubling and parallel chains. Lingua 119(7): 1035–1065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2008.11.004.

Alexiadou, Artemis. 2006. Left dislocation (including CLLD). In The Blackwell companion to syntax, Volume I, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk, 668–699. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Ambridge, Ben, and Adele E. Goldberg. 2008. The island status of clausal complements: Evidence in favor of an information structure explanation. Cognitive Linguistics 19 (3). https://doi.org/10.1515/cogl.2008.014.

Brucart, José María, and Jonathan E. MacDonald. 2012. Empty categories and ellipsis. In The handbook of Hispanic linguistics, eds. José Ignacio Hualde, Antxon Olarrea, and Erin O’Rourke, 579–601. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Büring, Daniel. 2003. On D-trees, beans, and B-accents. Linguistics and Philosophy 26: 511–545. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1025887707652.

Cable, Seth. 2004. Predicate clefts and base-generation: Evidence from Yiddish and Brazilian Portuguese. Ms., MIT.

Campos, Héctor. 1986. Indefinite object drop. Linguistic Inquiry 17(2): 354–359.

Cann, Ronnie. 2011. Sense relations. In Semantics: An international handbook of natural language meaning, Volume 1, eds. Claudia Maienborn, Klaus von Heusinger, and Paul Portner, 456–479. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Carlson, Gregory N. 1977. Reference to kinds in English. PhD diss., University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 1998. Reference to kinds across language. Natural Language Semantics 6(4): 339–405. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1008324218506.

Cho, Eun, and Kunio Nishiyama. 2000. Yoruba predicate clefts from a comparative perspective. In Advances in African Linguistics, eds. Vicky Carstens and Frederick Parkinson. Trends in African Linguistics, 37–49. Trenton: Africa World Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1977. The movement nature of left dislocation. Linguistic Inquiry 8(2): 397–412.

Clark, Eve V. 1987. The principle of contrast: A constraint on language acquisition. In Mechanisms of language acquisition, ed. Brian MacWhinney, 1–33. London: Routledge.

Clark, Eve V. 1990. On the pragmatics of contrast. Journal of Child Language 17(2): 417–431. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0305000900013842.

Cruse, Alan. 2004. Meaning in language: An introduction to semantics and pragmatics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

de Vries, Mark. 2017. Across-the-board phenomena. In The Wiley Blackwell companion to syntax, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk, 1–31. New York: Wiley Online Library.

Depiante, Marcela A. 2001. On null complement anaphora in Spanish and Italian. Probus 13(2): 193–221. https://doi.org/10.1515/prbs.2001.003.

Erteschik-Shir, Nomi. 1973. On the nature of island constraints. PhD diss., MIT.

Escandell-Vidal, Victoria. 2011. Verum focus y prosodia: Cuando la duración (sí que) importa. Oralia: Análisis del Discurso Oral 14: 181–202.

Fanselow, Gisbert, and Anoop Mahajan. 2000. Towards a minimalist theory of wh-expletives, wh-copying, and successive cyclicity. In Wh-scope marking, eds. Uli Lutz, Gereon Müller, and Arnim von Stechow, 195–230. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Fox, Danny, and Uli Sauerland. 1996. Illusive scope of universal quantifiers. In Proceedings of the North East Linguistics Society, Vol. 26, 71–85.

Francom, Jerid. 2012. Wh-movement: Interrogatives, exclamatives, and relatives. In The handbook of Hispanic linguistics, eds. José Ignacio Hualde, Antxon Olarrea, and Erin O’Rourke, 533–556. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Frascarelli, Mara, and Roland Hinterhölzl. 2007. Types of topics in German and Italian. In On information structure, meaning and form: Generalizations across languages, eds. Kerstin Schwabe and Susanne Winkler, 87–116. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.100.07fra.

Goodhue, Daniel. 2018. On asking and answering biased polar questions. PhD diss., McGill University.

Grice, Herbert. 1975. Logic and conversation. In Syntax and semantics 3: Speech acts, eds. Peter Cole and Jerry Morgan, 41–58. New York: Academic Press.

Holmberg, Anders. 2016. The syntax of yes and no. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hooper, Joan, and Sandra Thompson. 1973. On the applicability of root transformations. Linguistic Inquiry 4(4): 465–497.

Horn, Laurence R. 2006. Speaker and hearer in neo-Gricean pragmatics. Journal of Foreign Languages 164: 2–25.

Huang, James. 1993. Reconstruction and the structure of VP: Some theoretical consequences. Linguistic Inquiry 24(1): 103–138.

Hunter, Julie. 2016. Reports in discourse. Dialogue & Discourse 7(4): 1–35. https://doi.org/10.5087/dad.2016.401.

Jackendoff, Ray. 1972. Semantic interpretation in generative grammar. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Jo, Jung-Min. 2013. Predicate contrastive topic constructions: Implications for morpho-syntax in Korean and copy theory of movement. Lingua 131: 80–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2013.02.003.

Karttunen, Lauri. 1974. Presupposition and linguistic context. Theoretical Linguistics 1(1–3): 181–194.

Kobele, Gregory Michael. 2006. Generating copies: An investigation into structural identity in language and grammar. PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles.

Koopman, Hilda. 1984. The syntax of verbs: From verb movement rules in the Kru languages to Universal Grammar. Dordrecht: Foris.

Laka, Itziar. 1990. Negation in syntax. On the nature of functional categories and projections. PhD diss., MIT.

Landau, Idan. 2006. Chain resolution in Hebrew V(P)-fronting. Syntax 9(1): 32–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9612.2006.00084.x.

López, Luis. 2009. A derivational syntax for informational structure. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Muñoz Pérez, Carlos. 2017. Cadenas e interfaces. PhD diss., University of Buenos Aires.

Muñoz Pérez, Carlos. 2021. Island effects with infinitival hanging topics. Snippets 40: 4–6.

Murphy, M. Lynne. 2003. Semantic relations and the lexicon: Antonymy, synonymy and other paradigms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nunes, Jairo. 2004. Linearization of chains and sideward movement. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Olarrea, Antxon. 2012. Word order and information structure. In The handbook of Hispanic linguistics, eds. José Ignacio Hualde, Antxon Olarrea, and Erin O’Rourke, 603–628. New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

Potts, Christopher. 2005. The logic of conventional implicatures. New York: Oxford University Press.

Pullum, Geoffrey K., and Kyle Rawlins. 2007. Argument or no argument? Linguistics and Philosophy 30(2): 277–287.

Quer, Josep, and Luis Vicente. 2009. Semantically triggered verb doubling in Spanish unconditionals. Handout from the 19th Colloquium on Generative Grammar (CGG19), Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain, April 1-3, 2009.

Real Academia Española y Asociación de Academias de la Lengua. 2009. Nueva gramática de la lengua española, Vol. 2. Madrid: Espasa Libros.

Roberts, Craige. 1996. Information structure: Towards an integrated formal theory of pragmatics. In OSUWPL volume 49: Papers in semantics, eds. Jae Hak Yoon and Andreas Kathol, 35–57. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Dept. of Linguistics.

Rooth, Mats. 1992. A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 1(1): 75–116.

Saab, Andrés. 2011. On verbal duplication in River Plate Spanish. In Romance languages and linguistic theory, eds. Janine Berns, Haike Jacobs, and Tobias Scheer, 305–322. Leiden: John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/rllt.3.18saa.

Saab, Andrés. 2017. Varieties of verbal doubling in Romance. Isogloss. A journal on variation of Romance and Iberian languages 3(1): 1. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/isogloss.43.

Saab, Andrés. 2019. Sobre el locus de la expresividad. Paper presented at the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Salzmann, Martin. 2012. Deriving reconstruction asymmetries in Across the Board movement by means of asymmetric extraction + ellipsis. In Comparative Germanic syntax: The state of the art, eds. Peter Ackema, Rhona Alcorn, Caroline Heycock, Dany Jaspers, Jeroen Van Craenenbroeck, and Guido Vanden Wyngaerd, Vol. 191, 353–386. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

Samko, Bern. 2016. Syntax & information structure: The grammar of English inversions. PhD diss., University of California, Santa Cruz.

Šimík, Radek. 2020. Doubling unconditionals and relative sluicing. Natural Language Semantics 28(1): 1–21.

Simons, Mandy. 2007. Observations on embedding verbs, evidentiality, and presupposition. Lingua 117(6): 1034–1056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2006.05.006.

Simons, Mandy, Judith Tonhauser, David Beaver, and Craige Roberts. 2010. What projects and why. In Proceedings of SALT 20, eds. Nan Li and David Lutz, 309–327. Ithaca: CLC Publications.

Szabolcsi, Anna, and Terje Lohndal. 2017. Strong vs. weak islands. In The Wiley Blackwell companion to syntax, second edition, 1–51. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Takano, Yuji. 1995. Predicate fronting and internal subjects. Linguistic Inquiry 26(2): 327–340.

Trinh, Tue. 2009. A constraint on copy deletion. Theoretical Linguistics 35(2–3): 183–227. https://doi.org/10.1515/thli.2009.011.

Urmson, James O. 1952. Parenthetical verbs. Mind LXI(244): 480–496. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/lxi.244.480.

Van Valin, Robert. 1993. A synopsis of Role and Reference Grammar. In Advances in Role and Reference Grammar, ed. Robert Van Valin, 1–164. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Verdecchia, Matías. 2021. Impossible presuppositions. On factivity, focus, and triviality. Glossa: A journal of general linguistics 6(1): 1–29. https://doi.org/10.16995/glossa.5879.

Vicente, Luis. 2007. The syntax of heads and phrases: A study of verb (phrase) fronting. PhD diss., Leiden University.

Vicente, Luis. 2009. An alternative to remnant movement for partial predicate fronting. Syntax 12(2): 158–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9612.2009.00126.x.

Zubizarreta, María Luisa. 1999. Las funciones informativas: Tema y foco. In Gramática descriptiva de la lengua española, eds. Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte, 215–244. Madrid: Espasa Calpe.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the editor, Martin Salzmann, and to three anonymous NLLT reviewers for their valuable observations and suggestions. Special thanks go to Andrés Saab and Jenneke van der Wal for their comments on the original manuscript. We would also like to thank the audiences of Romania Nova VIII, Going Romance 31, Newcastle University, Leiden University Center for Linguistics, and to the members of the BA-LingPhil group for their feedback on previous versions of (parts of) this research. Carlos Muñoz Pérez acknowledges financial support by the ANID/FONDECYT project 3190813.

Funding

This research is supported by the ANID/FONDECYT research project number 3190813 (Muñoz Pérez), and a doctoral scholarship granted by CONICET (Verdecchia).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Muñoz Pérez, C., Verdecchia, M. Predicate doubling in Spanish: On how discourse may mimic syntactic movement. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 40, 1159–1200 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-022-09536-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-022-09536-3