Abstract

Predicate fronting with doubling (also known as the predicate cleft) has long been a challenge for theories of syntax that do not predict the pronunciation of multiple occurrences. Previous analyses that derive the construction via syntactic movement, including those attributing verb doubling to the formation of parallel chains (e.g., Aboh 2006; Kandybowicz 2008), are incompatible with remnant movement (Müller 1998), which does not give rise to doubling. This article presents data from the predicate fronting construction in Yiddish, in which verbs always double but complements never do. I argue that these seemingly contradictory pronunciation facts can be reconciled even if one assumes that phrasal movement and head movement are both syntactic. More specifically, the pronunciation of occurrences in Yiddish (doubled or not) follows from the general conditions on Spell-Out (or Transferpf) defined by Collins and Stabler (2016), modified only to accommodate syntactic head movement. Post-syntactic PF repairs are thus not required to account for the facts of the Yiddish predicate fronting construction. If such repairs are needed to generate doubling phenomena in other languages, they should be explicitly defined so as to modify or override the predictions of default Spell-Out conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

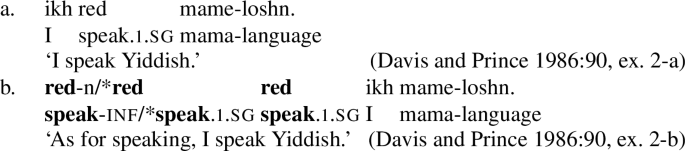

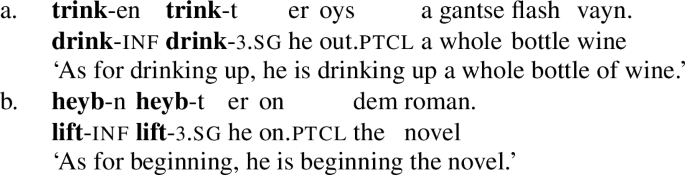

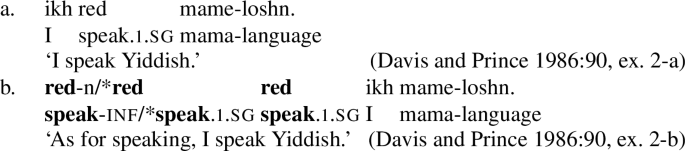

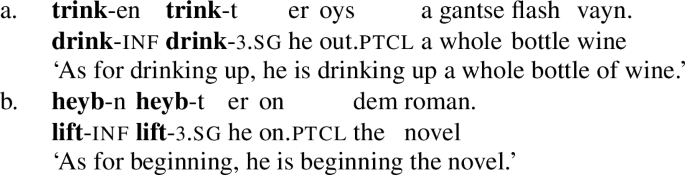

Predicate fronting with doubling, also known as the predicate cleft, has long posed a problem for theories of syntax that predict the pronunciation of just one occurrence of a moved element. The basic pattern is illustrated with an example from Yiddish (1), which will be the focus of this article. (Doubled elements will always be printed in boldface.)

-

(1)

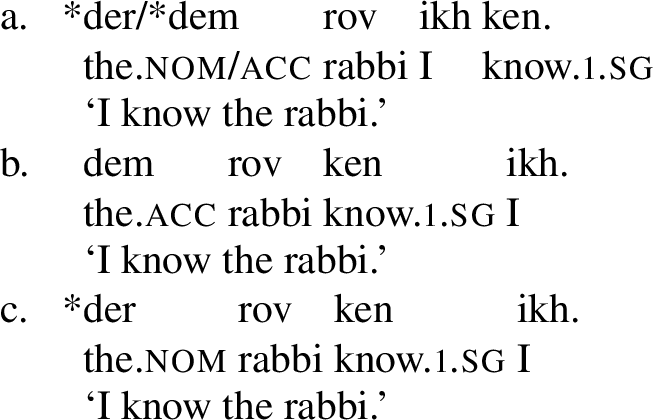

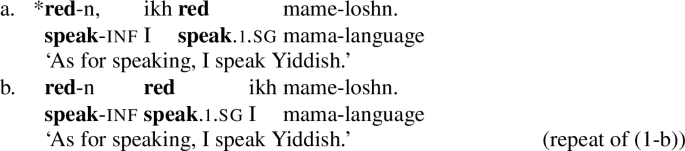

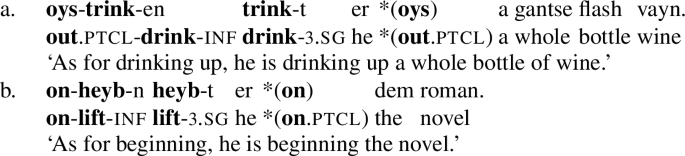

In several respects, the Yiddish pattern is typical of the predicate fronting construction that has been documented in many typologically diverse languages (see Kandybowicz 2008:80 for a list of references). First, when a finite verb is topicalized, two copies are obligatorily pronounced—the higher copy marked with non-finite morphology, and the lower copy marked for tense.Footnote 1 Second, as in Hebrew (Landau 2006), Polish (Bondaruk 2009), and Russian (Aboh and Dyakonova 2009), verbs in Yiddish can be topicalized along with their complements (2), suggesting that the fronting operation can target a phrase rather than a bare verbal head. Regardless of where the complement is pronounced—whether after the second copy of the verb (1-b) or after the first copy (2)—it is never doubled.

-

(2)

If both patterns involve VP movement (evidence for this view will be presented in Sect. 2), then the syntax should have some principled way of accounting for the obligatory doubling of verbs and the obligatory non-doubling of complements.

The goal of this article is to arrive at a set of explicit conditions on Spell-Out that account for these seemingly contradictory pronunciation facts. I will show that they actually follow from quite general principles governing the pronunciation of syntactic objects, defined by Collins and Stabler (2016) and modified only to accommodate syntactic head movement. Adopting such explicit conditions on Spell-Out—an algorithm—serves two purposes: (i) the conditions show precisely why the predicate fronting construction is initially problematic (i.e., applying them to derivations makes incorrect predictions), and (ii) they show how the predictions are altered when modifications are introduced to handle an ostensibly unrelated phenomenon: syntactic head movement.

The rest of the article is organized as follows: Sect. 2 provides evidence for a movement-based approach to the verb doubling construction in Yiddish. Sect. 3 defines the initial set of conditions on Spell-Out (or Transferpf), which are drawn from the minimalist framework of Collins and Stabler (2016) and assume the copy theory of movement. These Spell-Out conditions make correct predictions with respect to the obligatory non-doubling of complements (under remnant movement), but they require modification in order to capture syntactic head movement, a phenomenon that Collins and Stabler (2016) do not address. Specifically, an update is needed to prevent the pronunciation of multiple occurrences of moved heads—an incorrect prediction of the original Spell-Out conditions. Sect. 4 demonstrates why a natural consequence of this independently necessary modification is verb doubling in the predicate fronting construction in Yiddish (if not also in a closely related language, German). Finally, Sect. 5 presents some conclusions about the nature of PF repairs, arguing that if they are necessary to account for other kinds of doubling phenomena, then they must be defined in such a way that they modify or override the predictions of the default Spell-Out conditions.

2 Movement

In the literature on the verb doubling construction in Yiddish, most syntacticians have concluded that the first occurrence of the verb is the result of movement (Waletzky 1980; Davis and Prince 1986; Källgren and Prince 1989; Hoge 1998; Cable 2004). Although many details of their analyses differ,Footnote 2 the basic evidence for movement is widely accepted.

2.1 Evidence for movement

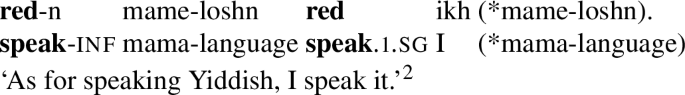

Yiddish exhibits the Germanic verb-second (V2) pattern, as shown in (3).

-

(3)

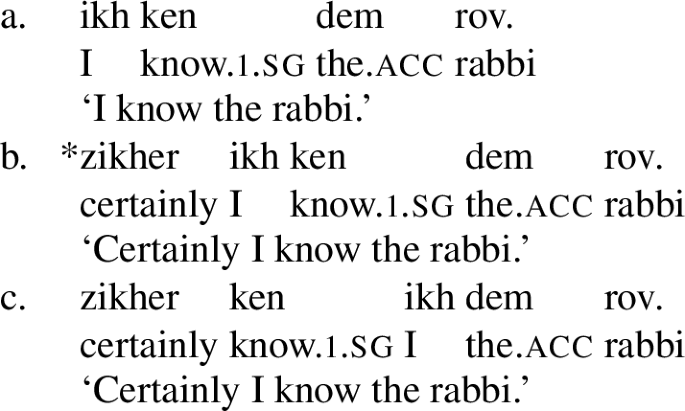

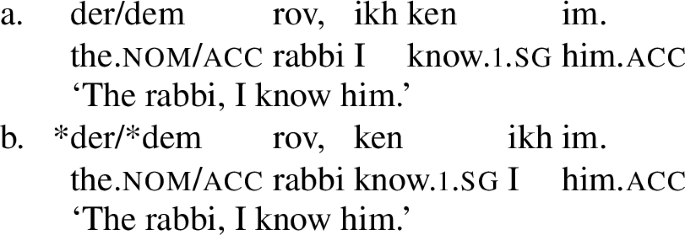

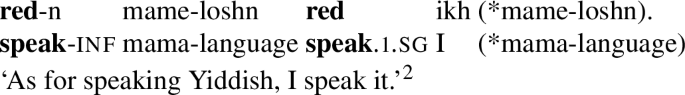

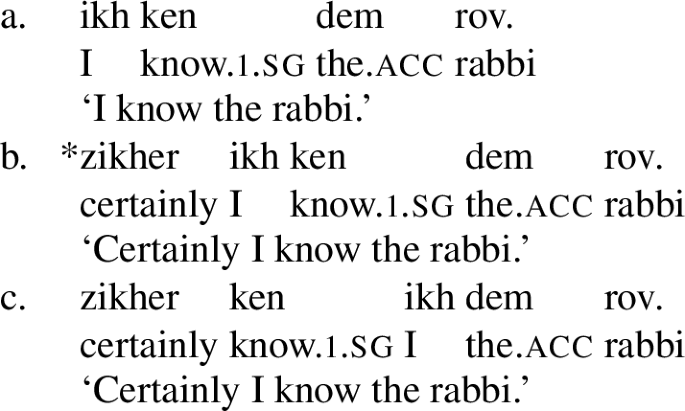

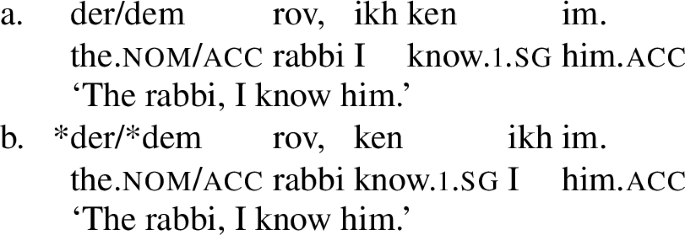

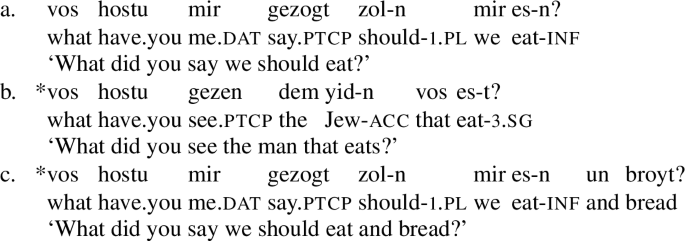

Like the adverb zikher ‘certainly,’ topicalized objects must immediately precede the finite verb (4). Left-dislocated DPs, however, cannot (5). Note also that the topicalized object in Yiddish is marked for the accusative case, which is not a requirement of left-dislocated DPs.

-

(4)

-

(5)

Finally, like the adverb in (3) and the topicalized object in (4)—but unlike the left-dislocated DP in (5)—the initial infinitive in the verb doubling construction must immediately precede the finite copy (6). The fact that the infinitive is considered a preverbal constituent with respect to V2 has been taken as evidence that it does indeed move to that position (e.g., Davis and Prince 1986; Källgren and Prince 1989). The same is true for sentences in which the initial constituent clearly appears to be an entire VP, the infinitive along with its complement (7).

-

(6)

-

(7)

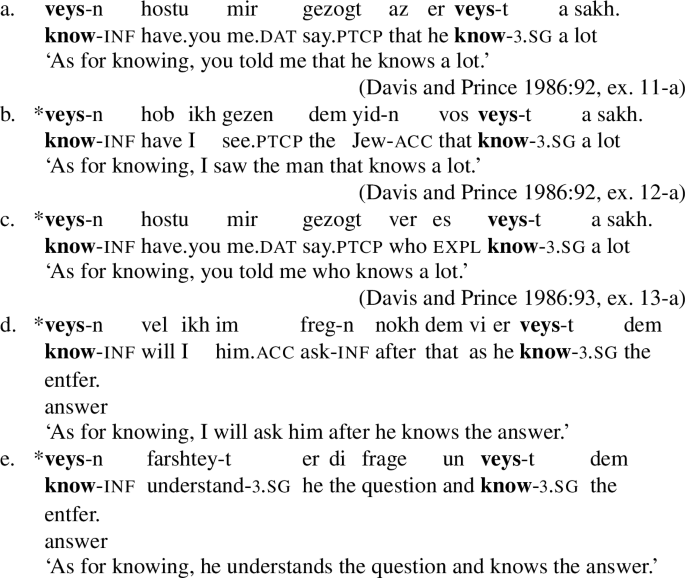

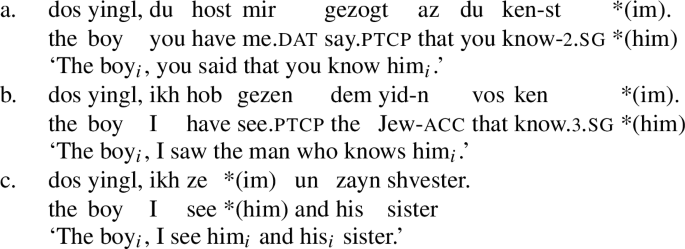

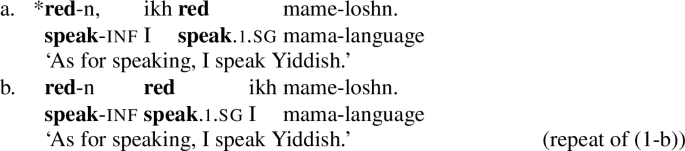

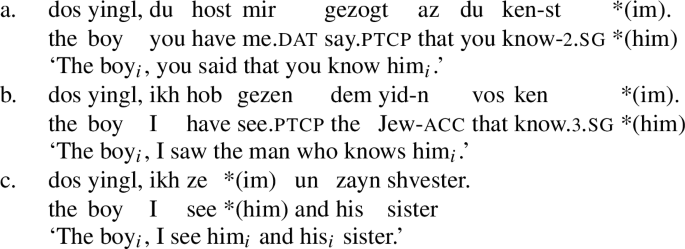

Additional support for the movement analysis comes from the domain of island effects. As Davis and Prince (1986) report, the first copy of the verbFootnote 3 can cross finite clause boundaries (8-a),Footnote 4 but it cannot be extracted from a relative clause (8-b) or a wh-island (8-c). My consultants also do not accept sentences in which the verb has been extracted from an adjunct island (8-d) or a coordinate structure (8-e).

-

(8)

These island sensitivities hold of other fronted constituents, including wh-items, but are not characteristic of left-dislocated DPs in Yiddish; a few examples are provided in (9) and (10). This suggests that while left-dislocated DPs are externally merged in a left peripheral position,Footnote 5wh-items and the infinitive of the predicate fronting construction both move to the left periphery.

-

(9)

-

(10)

These diagnostics have also been invoked in the analysis of predicate fronting and doubling in other languages (e.g., Abels 2001 for Russian; Landau 2006 for Hebrew; Bastos-Gee 2009 for Brazilian Portuguese). Such island effects are cited as evidence not only of movement in general, but also of the copy theory of movement in particular, since the pronunciation of an ordinarily silent occurrence suggests that syntactic movement must involve full copies rather than traces.

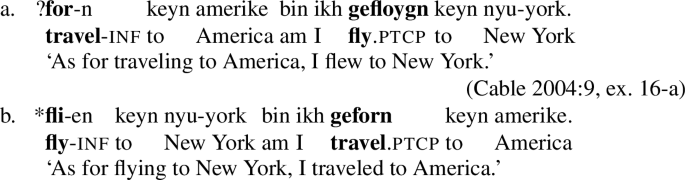

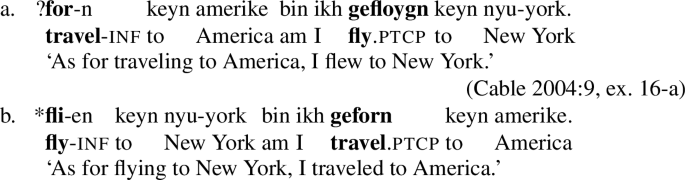

One observation that has been cited as “definitive evidence against any movement account” of the verb doubling construction (Cable 2004:4) is the apparent possibility of a lexical mismatch between the two verbs, “if and only if [the first verb] denotes a topic which the [second verb] provides more specific information about” (Cable 2004:9). A minimal pair is provided in (11); the question mark on (11-a) is copied directly from Cable (2004), while the star on (11-b) is extrapolated from his discussion.

-

(11)

Cable cites this mismatch as evidence that two verbs are base-generated independently. He does not provide a mechanism for ensuring a particular relationship between the two verbs (e.g., similarity or identity), or an explanation for the unacceptability of a mismatch involving a single verb in the left periphery with a coordinate structure below (like (8-e)). To account for the non-doubling of complements, which are also base-generated twice, one must assume a “strange condition on ellipsis” (Cable 2004:20–21) stipulating that one of two identical complements must be elided if and only if the head of the left peripheral VP is identical to the lower verbal head. (The verb, which is doubled rather than elided, is thus not subject to such a condition.) Again, there is no mechanism for determining which of the two complements is elided.

Cable’s mismatched examples from Yiddish have been reprinted numerous times in the predicate fronting literature on other languages (like Hebrew, Landau 2006:45; Dàgáárè, Hiraiwa and Bodomo 2008:821; Asante Twi, Hein 2017:8), precisely because those languages disallow mismatched predicates. However, I believe a mismatch is disallowed in Yiddish, too: None of the Yiddish grammars that discuss predicate fronting (e.g., Zaretski 1929; Mark 1978) mention the possibility of mismatched predicates, and I could not find any such examples through targeted searches in online corpora. My three consultants unequivocally rejected both sentences in (11). Finally, even Cable’s own primary consultant, Dovid Braun, confirmed with me that the example marked with a question mark (11-a) is extremely marginal, if acceptable at all.Footnote 6 For these reasons, I believe the reported judgments should not be relied upon as evidence that Yiddish actually allows mismatched predicates.

Cable states that the contrast between (11-a) and (11-b) is likely to have a semantic explanation. After all, whatever rules out (11-b) could also account for the unacceptability of its English translation, even though the English “as for” construction may not involve movement at all.Footnote 7 Note, additionally, that Cable’s sentence (11-a) involves the doubling of a PP complement, which on my account is not predicted to be possible even if the PPs were to match.

These facts lead me to conclude that the Yiddish grammar cannot generate sentences with mismatched predicates.Footnote 8 Consequently, such examples should not be cited as empirical evidence against a movement analysis, or in favor of an alternative analysis in which two verbs are externally merged.

2.2 Movement and discourse function

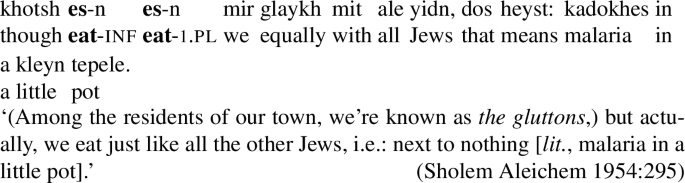

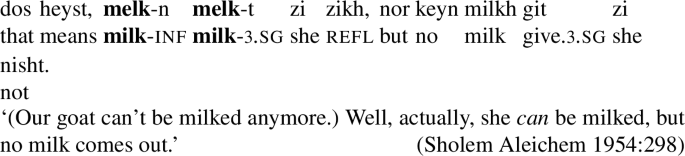

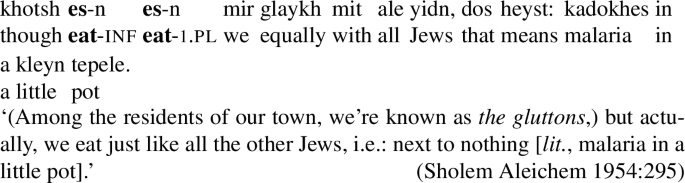

Many of the descriptions and analyses of Yiddish verb doubling have referred to the construction as a form of VP topicalization (Waletzky 1980; Davis and Prince 1986; Hoge 1998), and sometimes “finite verb topicalization” (Källgren and Prince 1989). A full discussion of its discourse status is beyond the scope of this article, which focuses on multiple vs. single copy pronunciation. However, it is worth mentioning that predicate fronting generally requires a special pragmatic context—which explains why it can be challenging to elicit judgments on such sentences. One common function of the construction is to introduce a contrast between the predicate (which is doubled) and some previously mentioned predicate, as in the following two literary examples. The immediate context of each sentence is provided in parentheses in the translations.

-

(12)

-

(13)

These particular examples were chosen because audiobooks narrated by Yiddish-speaking actors are available online.Footnote 9 The recordings make it clear that the fronted occurrence of the verb is pronounced with strong emphasis, marked by a prosodic contour known as the “rise-fall” (Burdin 2017). In these examples, there is a very steep rise in pitch with a peak on the stressed syllable of the infinitive, making the pitch range from the infinitive to the end of the clause unusually wide (Rachel Steindel Burdin, p.c.). Use of the rise-fall contour is frequently involved in topicalization, and I will assume for this analysis that the rise in both pitch and intensity is symptomatic of the verb’s bearing a topic feature that also triggers movement in the syntax.

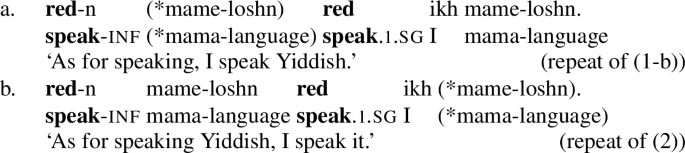

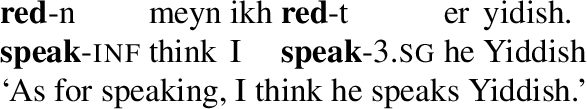

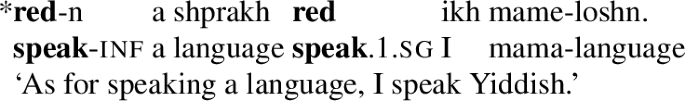

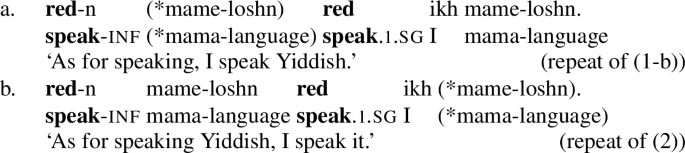

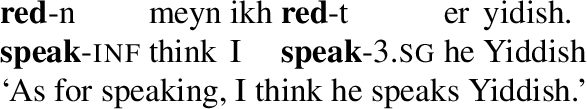

In analyses of predicate fronting, there is a tradition of translating sentences in which only the verb is pronounced in the left periphery differently than sentences in which the complement is also pronounced there: ‘As for speaking, I speak Yiddish’ in (1-b) vs. ‘As for speaking Yiddish, I speak it’ in (2). While I follow this trend here, the two structures may not necessarily have such a difference in their interpretation. For example, when asked for sentences that are natural continuations of these two examples, native speaker consultants provided identical responses (…ober ikh ken es nisht leyenen ‘but I can’t read it’). Even when I provided my consultants with scenarios meant to elicit the use of one but not the other structure (V vs. VP in the left periphery), consultants were reluctant to say they couldn’t be used interchangeably. Again, the discourse status of the various options awaits an in-depth analysis.

Proceeding with the assumption that the relationship between the doubled verbs in Yiddish is the result of movement, the following sections will propose explicit conditions on Spell-Out that predict which occurrence(s) of syntactic objects are pronounced in which position(s). These conditions are necessary both to illustrate why the construction is theoretically puzzling (the doubling of verbs vs. non-doubling of complements) and ultimately to highlight the predictions of independently motivated modifications to those conditions.

3 Conditions on Spell-Out

3.1 Remnant movement

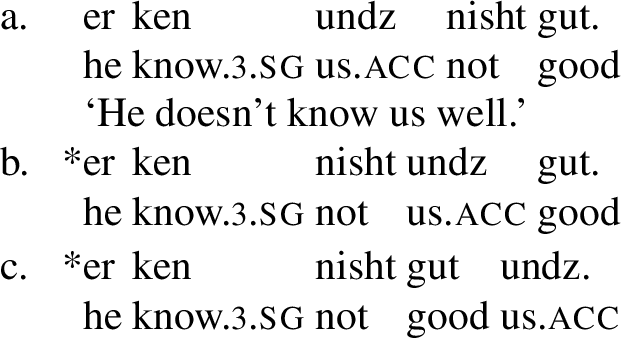

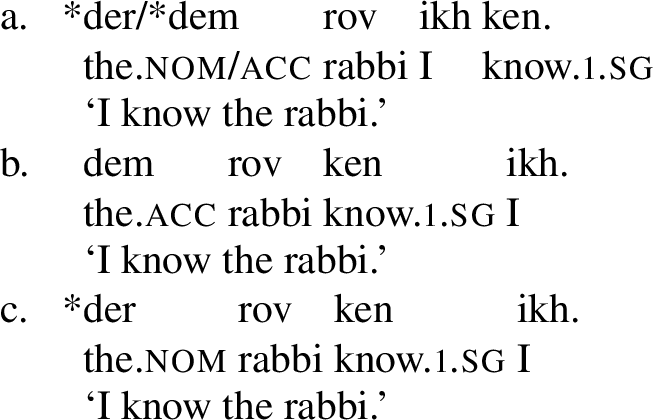

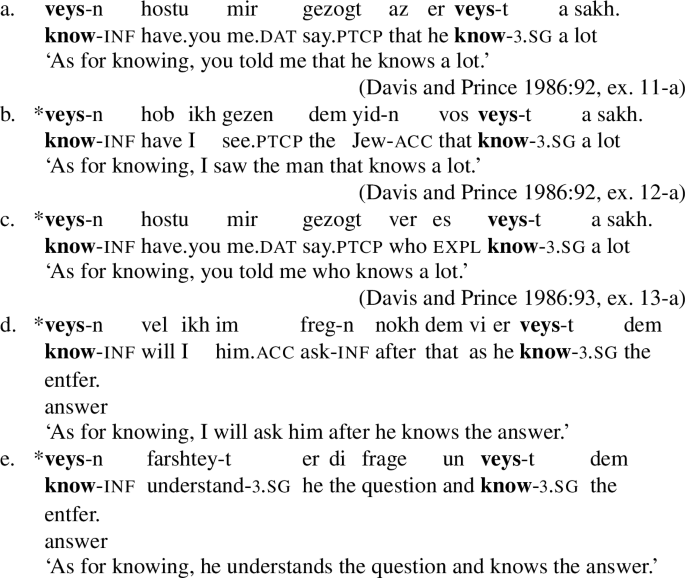

The fact that complements do not double in the predicate fronting construction, shown in (14), is perhaps the least surprising facet of the predicate fronting puzzle. It is therefore a suitable starting point.

-

(14)

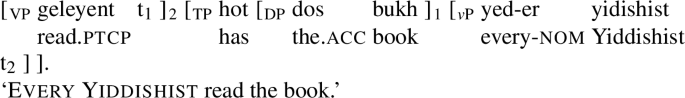

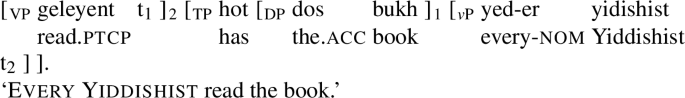

The unacceptability of sentences with two overt complements follows straightforwardly from a theory of syntax that allows for the fronting of incomplete (or “remnant”) categories. Remnant movement is the phenomenon whereby a phrase undergoes movement only after the extraction of some smaller element from it earlier in the derivation. Consider the Yiddish sentence (15), modeled after a German sentence that has been cited as evidence for remnant movement (Müller 1998:ix, ex. 1).

-

(15)

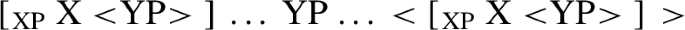

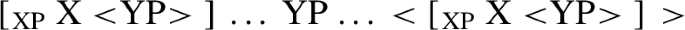

Within the fronted VP, only the V geleyent is pronounced. The intuition is that an earlier operation extracts the DP dos bukh from the VP and generates a silent trace, which remains silent within the fronted VP. The fronted VP is thus a “remnant category” with respect to the DP. The general pattern is schematized in (16), with copies rather than traces.

-

(16)

According to the Inclusiveness Condition (Chomsky 1995:225), a principle of minimalist syntax stipulating that syntactic operations like Merge cannot generate new objects such as silent traces, all occurrences of an element like YP in (16) are syntactically identical and eligible for phonetic realization. Under typical conditions, one might expect Spell-Out to result in the pronunciation of the highest copy of a moved object rather than a middle one,Footnote 10 although it is the middle occurrence of YP that is pronounced here.

In order to capture the intuition behind remnant movement within a minimalist framework that invokes copies rather than traces, I adopt the Spell-Out conditions of Collins and Stabler (2016). Their formalization of minimalist syntax is particularly appealing because it provides the analyst a set of precise definitions with which to evaluate the predictions of novel proposals—specifically, definitions regarding the syntactic occurrences that come to be pronounced in any given derivation. Because their formalization was not designed for Yiddish, and because the authors themselves “put aside issues such as how to handle the copies formed in predicate clefts” (Collins and Stabler 2016:71), the fact that their system can be applied to the Yiddish predicate fronting construction (albeit with one modification) lends support to it.

The Spell-Out conditions are provided in (17) and explained in the paragraphs that follow.

-

(17)

Spell-Out conditions for phrasal movement, including remnant movement (based on Collins and Stabler 2016, definitions 40 and 41-c):

-

a.

X ∈ {X,Y} is final in a syntactic object SO iff there is no Z contained in (or equal to) SO such that Z immediately contains X, and Z contains the set {X,Y}. Otherwise, X is nonfinal in SO.

-

b.

If SO = {X,Y} and X in SO is final in Phase but Y is not, TransferPF(Phase, SO) = TransferPF(Phase, X).

-

a.

Condition (17-a) specifies the occurrences of syntactic objects (i.e., lexical item tokens or sets of such syntactic objects) that are evaluated to be “final” or “nonfinal” based on their structural positions. Condition (17-b) then states that only “final” occurrences are phonetically realized after TransferPF (Spell-Out) of a phase, the unit to which Transfer applies. The first condition makes reference to the notions “immediate containment” and “containment,” which Collins and Stabler (2016:46) define as follows: “immediate containment” is set membership (i.e., Z immediately contains X iff X ∈ Z), and “containment” includes both immediate containment and transitive containment extending down the tree (e.g., Z contains X if Z immediately contains X, or if Z immediately contains Q which immediately contains X, etc.). In other words, a syntactic object immediately contains each of its daughters, whereas a syntactic object contains each of its daughters, granddaughters, great-granddaughters, etc.

With these definitions in mind, the predictions of the Spell-Out conditions in (17) are illustrated in the following derivations. All occurrences with matching letter labels are assumed to be syntactically identical; the subscripts are for expository purposes only.

-

(18)

In this derivation, A1 is an element of the set {A,B} = C and raises to become the sister to C. According to (17-a), the occurrence A1 in {A,B} is nonfinal within D, because there exists a syntactic object (namely D itself) that immediately contains A (the occurrence A2) and also contains the set {A,B}. The occurrence A2 in {A,C} is final in D, however, because there exists no syntactic object that immediately contains an occurrence of A and also contains the set {A,C}. (D immediately contains an occurrence of A, but D does not contain the set {A,C}; rather, D is the set {A,C}.) B, C, and D are final in D by the same reasoning. Consequently, according to (17-b), transferring D to PF will yield the phonetic realization of A2 and B only, as we would normally expect in simple cases of syntactic movement.Footnote 11

Crucially for our purposes, the two-part definition in (17) also correctly predicts the occurrences that are pronounced under remnant movement. Consider the following derivation (19), which contains the subtree shown in (18). We will assume that E is a phase.

-

(19)

A1 is nonfinal in E because there is an object (D) that immediately contains A2 and also contains the set {A,B}. A2 is still considered final because there is no syntactic object anywhere that immediately contains an occurrence of A and also contains the set {A,C}. Now consider the occurrence A3 in {A3,B2} = C2, the moved remnant category. The occurrence A3 is nonfinal in E because there exists a syntactic object within E, namely D, that immediately contains an occurrence of A and also contains the set {A,B}. It follows from the same reasoning that C2, D, and E are final within E, while C1 is nonfinal. As a result, transferring E to PF will yield overt occurrences of B2 and A2 only.

In this way, the Spell-Out conditions of Collins and Stabler (2016) correctly predict the pronunciation of occurrences under typical phrasal movement as well as remnant phrasal movement, without relying on the generation of silent traces.

3.1.1 Remnant movement across a phase

One complication of this approach to pronunciation under remnant movement relates to derivation by phase. A fragment of the derivation of the Yiddish remnant movement sentence in (15) is shown in (20). Again, all occurrences of a given object are syntactically identical and numbered for expository purposes only.

-

(20)

In order for the object DP dos bukh ‘the book’ to be pronounced above the subject DP yeder yidishist ‘every Yiddishist,’ and in order for the VP geleyent <dos bukh> ‘read <the book>’ to eventually move to the left periphery, both of these phrases must move through the edge of the vP phase. This is because TransferPF applies to phases (17-b), and if one adopts the Phase Impenetrability Condition (PIC; Chomsky 2001:13), then any objects which remain in the domain (complement) of v become inaccessible once they are spelled out. This inaccessibility could be due to the removal of syntactic structure, or to a stipulation that such structure is invisible to higher operations (Chomsky et al. 2019:240–241). In either case, this inaccessibility creates a “lethal problem” for the pronunciation of occurrences (Collins and Stabler 2016:73): if Spell-Out renders the base-generated VP in (20) inaccessible to the condition that determines the finality of occurrences (17-a), then the two higher occurrences of the DP dos bukh (marked #2 and #3) are both predicted to be final. DP dos bukh2 is final in vP because there is no object that immediately contains an occurrence of the DP and also contains the set {DP dos bukh,[middle] v′}. DP dos bukh3 in the fronted VP is also final, because the only syntactic object that immediately contains an occurrence of DP dos bukh (namely the highest v′) does not contain the accessible set {V geleyent,DP dos bukh}. The “lethal problem” for remnant movement is therefore the doubling of the object, whenever the object and the VP move to positions out of the phase in which the VP was base-generated.

This problem—that “if an occurrence A were nonfinal before Transfer, it may become final after Transfer” (Collins and Stabler 2016:73)—leads the authors to sketch out (in an unpublished Appendix) an alternative conceptualization of Transfer that preserves syntactic structure while rendering it inaccessible to operations like Merge. However, in this article I adopt the strict assumption that any lower structure that has been spelled out in a phase is completely invisible for the determination of final and nonfinal occurrences at a higher phase. If this strict version of the PIC is to be maintained, then the derivation of remnant movement that causes doubling (20) must be replaced by a more optimal (less costly) alternative that does not cause doubling. A minimally different derivation is one in which the landing sites for the DP and remnant VP—the inner and outer vP specifiers, respectively—are reversed, as in (21):

-

(21)

Here, the DP dos bukh3 is final in vP because there is no object that immediately contains an occurrence of the DP and also contains the set {DP dos bukh,[highest] v′}. DP dos bukh2 is nonfinal in vP because there is an object (namely vP itself) that immediately contains an occurrence of the DP and also contains the set {V geleyent,DP dos bukh2}. (Crucially, neither of these calculations requires the VP complement of vP to be accessible.) When the remnant VP fronts to the left periphery in Spec,TopP (not shown here), the DP dos bukh contained within that left peripheral VP will also be nonfinal, because both Spec,vP positions will still be accessible at the TopP phase. This derivation thus yields correct predictions about remnant movement, if one adopts the Spell-Out conditions (17) and the strict assumption that spelled out structure is completely invisible for the purposes of calculating the finality of occurrences.

The structure shown in (21) could be derived in a few different ways. One would involve movement of the DP dos bukh to Spec,vP followed by movement of the remnant VP to an inner specifier, as in the “tucking in” approach of Richards (1999). Tucking in the VP below the landing site of the DP is difficult to define within the framework of Collins and Stabler (2016), since it requires that the vP object formed by movement of the DP be dismantled and subsequently reconstituted with an intervening specifier (see Collins and Stabler 2016:59, fn. 9). Another way to derive (21) is to assume that the VP moves before the DP does. For example, the VP might raise to an inner Spec,vP and the DP contained within it might raise to an outer Spec,vP. This is reminiscent of smuggling, where movement of a phrase XP containing YP precedes the evacuation of YP from XP (Belletti and Collins 2021:3).Footnote 12 However, it is not clear what could motivate the extraction of a syntactic object from an inner to an outer vP specifier (e.g., according to theories of Agree).Footnote 13 Alternatively, the v head could bear features that trigger movement of both the DP and the VP; arguably it is the VP which is attracted first, because it is closer than the DP, giving rise to the structure shown in (21) and ruling out the structure shown in (20). While I remain agnostic about which of these approaches is correct, the derivations in this article will include movement arrows suggestive of the smuggling approach. In any event, I proceed with the assumption that the DP and remnant VP escape the vP phase by landing at specifiers in this specific configuration, such that the DP c-commands the VP.

This discussion is not meant to redefine “remnant movement” so that it always involves three instances of movement (smuggling of XP, extraction of YP from XP, and movement of XP) rather than two (extraction of YP from XP and movement of XP). In (21), we would still say that “remnant movement” involves extraction of the DP dos bukh from the VP and subsequent fronting of the remnant VP to the left periphery (not shown). Smuggling of the VP is thus a separate step that enables correct pronunciation when remnant movement involves occurrences across multiple phases.

3.1.2 Remnant VP movement and predicate fronting

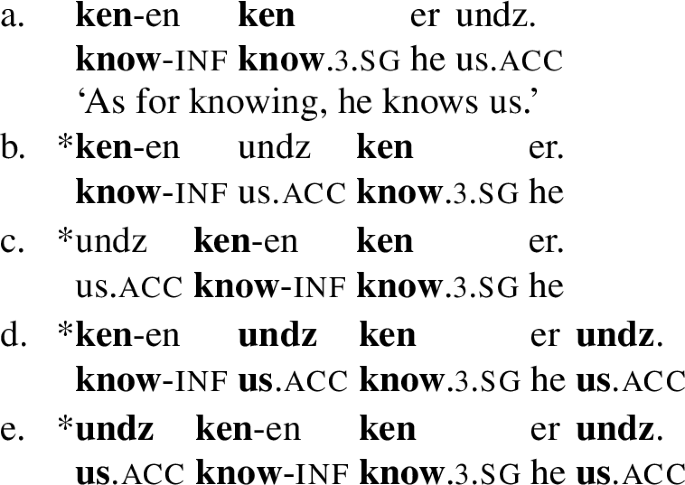

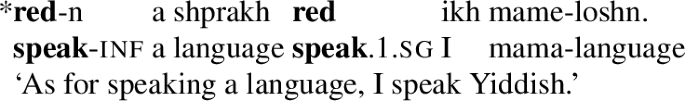

If the Spell-Out conditions in (17) are part of Universal Grammar, it follows that predicate fronting in Yiddish should never give rise to doubling of complements (the data are repeated in (22)).

-

(22)

If the complement DP mame-loshn ‘mama-language’ is able to undergo object shift to some intermediary position prior in the derivation to the fronting of the VP, then the occurrence of the DP contained in the fronted remnant VP will not be pronounced (yielding (22-a)). On the other hand, only if object shift does not occur is it possible, given these conditions, to pronounce an occurrence of the DP in the fronted VP (yielding (22-b)). This is essentially the analysis provided by Abels (2001) for predicate fronting in Russian and by Bondaruk (2009) for predicate fronting in Polish, in which a fronted “bare verb” is the result of remnant verb phrase movement after the evacuation of its complement.

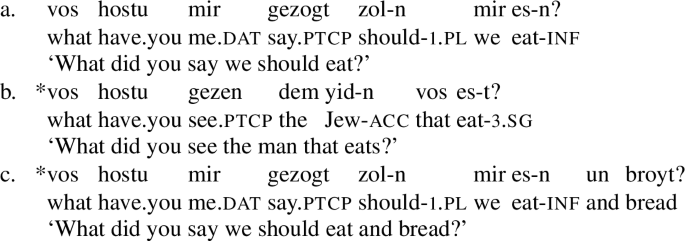

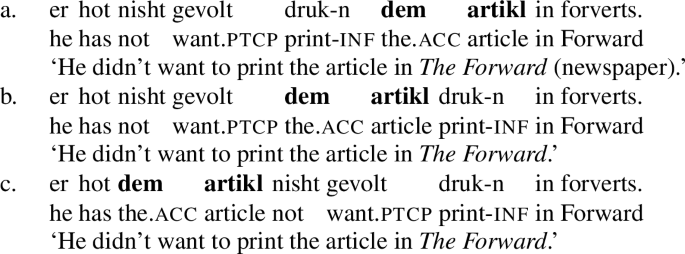

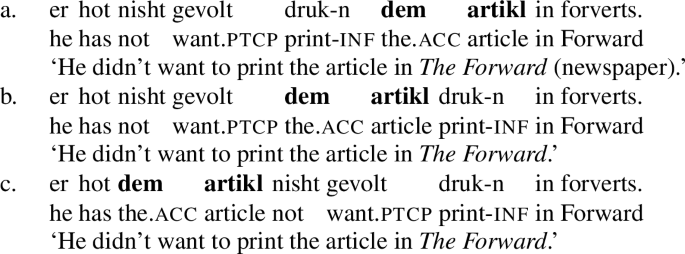

In order to account for the variation in where the complement is pronounced—it can be realized after the first or second copy of the verb—it is assumed that object shift itself is optional, consistent with the proposals of Johnson (1991:606) and Lasnik (2001).Footnote 14 Independent evidence for the optionality of object shift in Yiddish comes from the following alternation:

-

(23)

Sentence (23-a) suggests that the object DP dem artikl is free to remain in its base-generated position to the right of the verb (assuming Yiddish is SVO; Diesing 1997). The acceptability of (23-b) suggests that there must be a relatively low projection that can host shifted objects.Footnote 15 Finally, sentence (23-c) shows that the object can scramble past negation (presumably through Spec,vP).Footnote 16

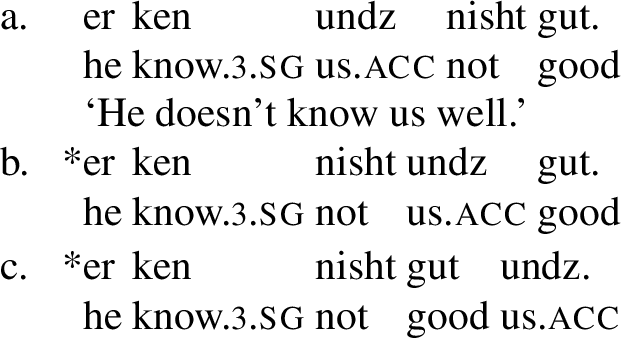

While the conditions under which the movement of the object occurs or does not occur are beyond the scope of the current study (see Diesing 1997 for discussion), it is important to note that weak pronominal objects differ from other definite objects in that they must move to a position above negation (Diesing 1997:393–394; see Thráinsson 2001 and Vikner 2006 for parallels in other Germanic languages). This observation will become relevant shortly.

-

(24)

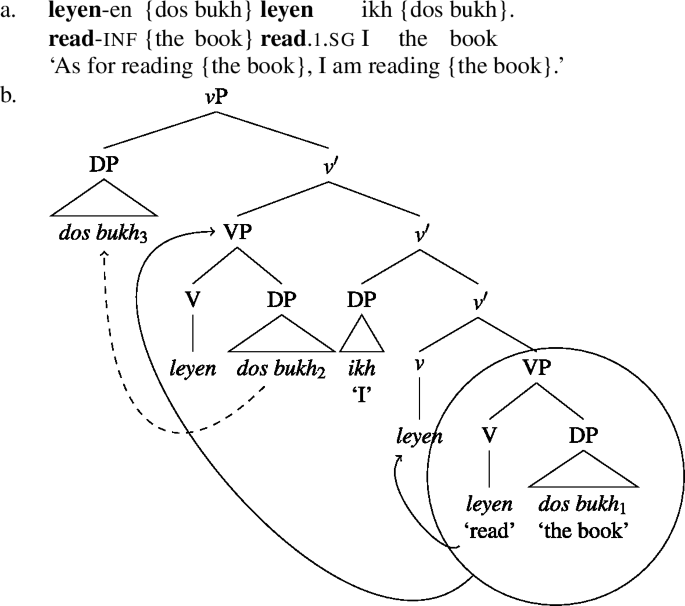

We can see how the Spell-Out conditions in (17) would apply in the predicate fronting construction to yield the pronunciation of just one copy of the object—after the first verb or after the second, but not in both places. Consider the sentence in (25-a), where curly braces indicate that the object must be pronounced in just one of two places. A fragment of the derivation of this sentence is shown in (25-b). Optionality of object shift is indicated with a dashed arrow, a convention adopted throughout the rest of the article.

-

(25)

If the VP pronounced in the left periphery is the result of movement (as argued in Sect. 2), then it must move through the edge of the vP phase in order to be accessible for further movement. If object shift to a high projection above negation is optional, presumably the DP must also pass through the edge of the phase. (The object’s ultimate landing site beyond the verb’s extended projection is not shown here, and its label is not important for our purposes.)

In the derivation shown in (25-b), the VP raises to Spec,vP, rendering the lower occurrence nonfinal (and silent) at Spell-Out, at which point it becomes inaccessible to higher operations. Assume that object shift (the dotted arrow) has occurred. The Spell-Out conditions in (17) predict that the occurrence DP dos bukh3 is final in vP. This is because there is no syntactic object anywhere that immediately contains an occurrence of the DP dos bukh and also contains the set {DP dos bukh,[highest] v′}. (Of course, if the object moves to some higher projection, e.g., above negation, the Spell-Out conditions predict that the object will be final and pronounced there rather than in Spec,vP.) The occurrence DP dos bukh2 is nonfinal; this is because within vP, there is a syntactic object (vP itself) that immediately contains the occurrence DP dos bukh3 and also contains the (accessible) set {V leyen,DP dos bukh2} in its inner specifier.

However, if object shift does not occur—so that there is no occurrence DP dos bukh3—then every occurrence of the DP is contained within an occurrence of VP. Without object shift, the occurrence DP dos bukh2 is final in vP. If the higher VP subsequently fronts to the left periphery, then the left peripheral VP will be final in TopP and it will contain the only pronounced occurrence of the DP object.

One of the predictions of this remnant movement approach to complements is that whenever object shift is obligatory, it should not be possible for the complement to be pronounced in the fronted VP. For example, because the movement of pronominal objects is obligatory (24), subsequent fronting of the VP should always be a case of remnant movement; thus the fronted VP should always contain a nonfinal (silent) occurrence of the pronominal object. This prediction is confirmed by my consultants:Footnote 17

-

(26)

As this discussion has shown, the formal Spell-Out conditions of Collins and Stabler (2016) yield the predictions of remnant movement, and therefore the obligatory single copy pronunciation of DP complements in the Yiddish predicate fronting construction. In order to evaluate whether the Spell-Out conditions make correct predictions with regard to occurrences of the verb—that the verb is obligatorily pronounced in two places—we first need to ensure that the minimalist framework of Collins and Stabler (2016) can handle simple instances of head movement.

3.2 Spell-Out conditions and head movement

The formal conditions specifying which occurrences of syntactic objects come to be pronounced at PF (17) refer neither to phrases nor to heads. As demonstrated in the previous section, they correctly predict the pronunciation of phrasal constituents. However, it turns out that the conditions are incompatible with head movement. In fact, Collins and Stabler (2016:43) specifically mention head movement as one of the topics not addressed in their formalization due to space limitations. We will therefore need to modify Collins and Stabler’s (2016) Spell-Out conditions to make correct predictions for the pronunciation of occurrences of syntactic heads before they can be applied to the verbal occurrences in the predicate fronting construction.

To demonstrate why these conditions on Spell-Out are incompatible with head movement, consider the simple case of V-to-v movement shown below in (27) for the Yiddish verb phrase red mame-loshn ‘speak Yiddish’ (specifiers not shown).

-

(27)

If we adopt the assumption that head movement is syntactic and involves the formation of complex head adjunction structures,Footnote 18 then applying the definition of “final” (17-a) to the occurrences of V in (27) gives rise to an unexpected result. The left occurrence of V red is final, because there exists no syntactic object that immediately contains an occurrence of V red and also contains the set {V red,v}. However, the right occurrence of V red is also final, because there exists no syntactic object that immediately contains an occurrence of V red and also contains the set {V red,DP mame-loshn}. As a result, the definition given in (17-b) predicts that two copies of the head red will be pronounced. In fact, the Spell-Out conditions predict that every instance of successive-cyclic head movement will give rise to a final, and thus phonetically overt, occurrence of the moved head. This is clearly an undesirable result, since head movement does not normally give rise to the pronunciation of multiple copies.

To avoid this problem, we appeal to the observation that adjunction involves the formation of syntactic objects consisting of multiple segments: [β α [β …]] (Chomsky 1986:7). Chomsky has posited an operation, Pair-Merge, to formalize such a multi-segment category whenever one object is adjoined to another:

Adjunction has an inherent asymmetry: X is adjoined to Y. Exploiting that property, let us take the distinction between substitution and adjunction to be the (minimal) distinction between the set {α,β} and the ordered pair <α,β>, α adjoined to β… For clarity, let us refer to substitution as Set-Merge and adjunction as Pair-Merge. (Chomsky 2000:133)

The notion that Pair-Merge forms adjunction structures has been repeated in Chomsky’s subsequent writings (e.g., Chomsky 2004:117–118; Chomsky 2008:146–147) and has also been assumed to apply to head movement (Chomsky 2015:12). We define Pair-Merge as follows:

-

(28)

Pair-Merge for adjunction:

Pair-Merge(X,Y) = <X,Y>

The most straightforward way to accommodate head movement within the Spell-Out conditions in (17) is to expand the definition of “immediate containment” to apply even in the presence of an intervening segment of a two-segment category, formed when X is adjoined to some other syntactic object Q:

-

(29)

Immediate containment:

Z immediately contains X iff X is a member of Z or <X,Q> is a member of Z.

Note that Collins and Stabler (2016:43) specifically name “Pair-Merge (adjunction)” as a topic that, like head movement, is not addressed in their formalization due to space limitations. The definitions in (28) and (29) are thus one way to fill a gap in their framework.

Returning to the head movement derivation in (27), we can already see the effect of this modification. The externally merged V red is nonfinal in vP because there exists a syntactic object (namely vP itself) that immediately contains <V red,v> and also contains the set {V red,DP mame-loshn}. The complex v head is final because there is no object that immediately contains v and also contains the set {v,VP}. In this way, the next higher head “counts” as an occurrence of the immediately lower head and ensures that the lower head is nonfinal.

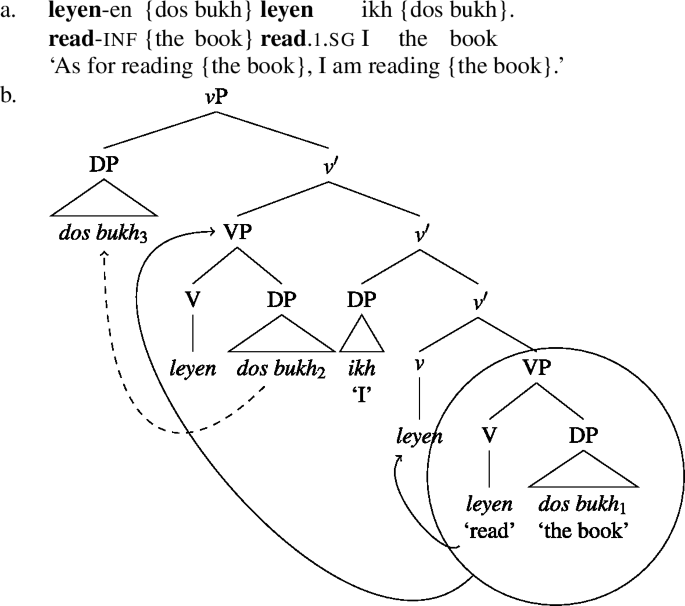

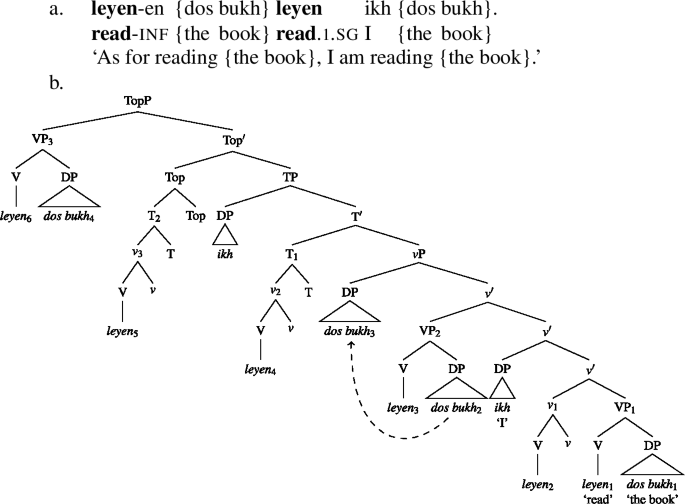

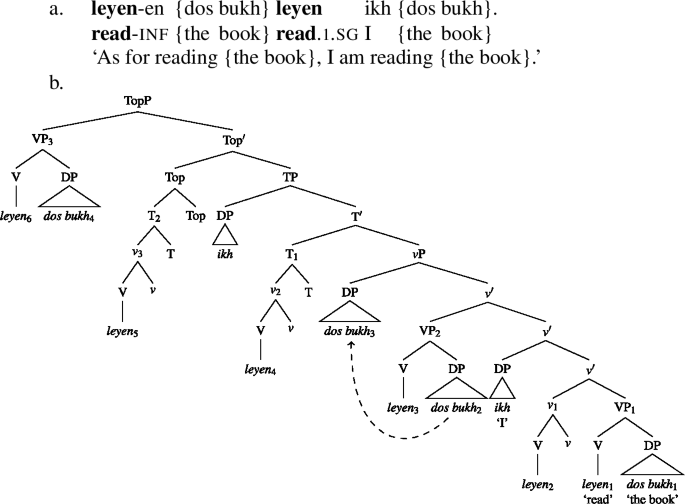

Once again, a fragment of the derivation of the sentence (25-a) leyen-en {dos bukh} leyen ikh {dos bukh} ‘As for reading {the book}, I am reading {the book}’ is shown in (30)—this time with verb movement to T and the addition of complex head adjunction structures. Here we focus only on the occurrences of V leyen ‘read’ that are involved in head movement up the tree (i.e., occurrences #1, #2, and #4).

-

(30)

The externally merged verb in {V leyen1,DP dos bukh} is nonfinal in the vP phase: there is a syntactic object (the lowest v′) that immediately contains <V leyen2,v> and also contains the set {V leyen1,DP dos bukh}. Because V leyen1 is nonfinal, when TransferPF applies to the phase it will be silent. The strict assumption of the PIC also means that once the lower VP is transferred to PF it is no longer visible for the purposes of calculating the finality of occurrences higher in the tree.

The next higher head, the complex v1, is also predicted to be nonfinal in TP: this is because T′ immediately contains <v2,T> and it also contains the set  (strikethrough represents that the VP is inaccessible after phase transfer). The highest complex head, T, is final in TP: there is no syntactic object that immediately contains T (or any <T,Q>) and also contains the set {T,vP}.

(strikethrough represents that the VP is inaccessible after phase transfer). The highest complex head, T, is final in TP: there is no syntactic object that immediately contains T (or any <T,Q>) and also contains the set {T,vP}.

As the verb moves successive-cyclically up the tree, forming increasingly more complex head adjunction structures, each complex head thus renders the next lower head nonfinal. T is the highest complex head, and it is the only one that is final. While this update to “immediate containment” makes correct predictions in simple cases of syntactic head movement, the analysis obviously does not address the classic problem of head movement’s violating the Extension Condition (Chomsky 1995:190–191), since head adjunction does not extend the tree at the root. However, as a rule on Spell-Out, it is both consistent with the spirit of the syntactic framework of Collins and Stabler (2016) (where finality is determined solely by structural configurations) and descriptively adequate, as it allows for a complex head to “count” as an occurrence of the next lower head and thereby render it nonfinal.

With this update in mind, we can return to the second puzzle of the Yiddish predicate fronting construction: the obligatory doubling of verbs. As will be demonstrated, the doubling of verbs actually does not require any additional modifications to the Spell-Out conditions.

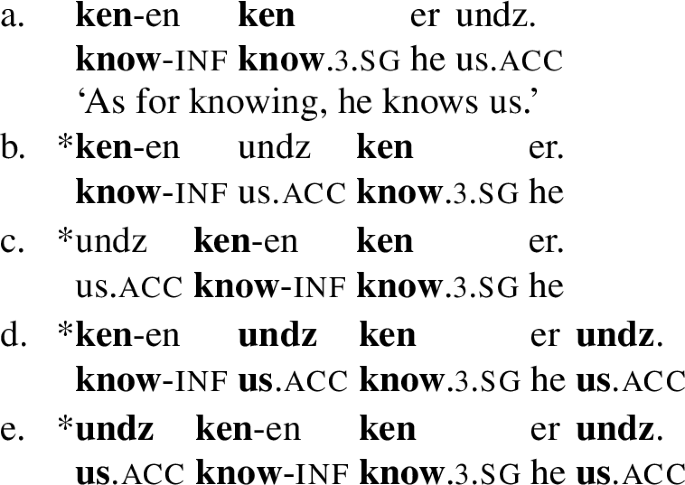

4 Verb doubling

Given that the conditions on Spell-Out defined thus far allow for remnant movement, the doubling of verbs seems (at first glance) to be problematic. In Sect. 2, it was claimed that predicate fronting involves the movement of a phrase rather than a bare verbal head. If the object shifts out of the VP prior in the derivation to the fronting of the VP, then the occurrence of the object in the left peripheral VP will be nonfinal. Extending this logic, if the verb moves out of the VP prior to the fronting of the VP—which it seems to do obligatorily, in order to move to v and then to T where it receives tense marking—one might expect the fronted VP to be a remnant category with respect to the verb, as well. Thus the fronted VP should never contain a final (pronounced) copy of the verb; the verb should only be pronounced once, at T.

4.1 Against parallel chains

One attempt to resolve this problem comes from the analysis of Aboh (2006), Kandybowicz (2008), and Aboh and Dyakonova (2009), who assume that verb doubling in the predicate fronting construction arises through parallel chain formation. According to Aboh and Dyakonova (2009), parallel chains are formed when a single syntactic occurrence (V or VP) checks the features of two different probing heads (under their analysis, Asp[ect] and Top/Foc). These two chains are believed to be formed simultaneously, and the two feature-checking relations are independent. According to their theory, the highest copy of the verb in each chain must be phonetically realized at PF—giving rise to doubling—while any lower occurrences are nonfinal and thus phonetically null.

In ordinary cases of VP remnant movement like (15), it is generally assumed that the object DP first raises to some specifier position (perhaps on its way to Spec,NegP), and then the remnant VP raises to an even higher specifier position (perhaps on its way to Spec,TopP). These two movement operations involve two different probes and two different goals. Under parallel chain formation, however, two different probes target the same verbal goal, V(P). It is this difference that is postulated to give rise to doubling only in the case of verbs.

Reconciling this approach with a grammar that defines the finality of occurrences based solely on syntactic structure is a major challenge. One would presumably need to define an additional condition on Spell-Out, applicable only to parallel chains, according to which two occurrences of the verb will be evaluated as final. One candidate for such a condition is given in (31).

-

(31)

(Hypothetical) Spell-Out condition for parallel chains:

-

a.

Two probing features, A and B, form two parallel chains by simultaneously targeting the same goal, either X or its maximal projection XP.

-

b.

The occurrence of X that is final (see (17-a)) is evaluated independently in each chain.

-

a.

There are a number of reasons why such an explicit Spell-Out rule for parallel chains should be avoided. First, in order to guarantee that only the verb can have more than one final occurrence, the definition in (31) must make reference to heads of “chains,” which are not operative in the original Spell-Out conditions. As one reviewer states, defining a new rule for parallel chains severely compromises the formal elegance of the conditions from Collins and Stabler’s (2016) framework, which depend only on the structural positions of objects. The conditions in (31) essentially allow occurrences of the same syntactic object to ignore one another just in case they have been copied as the result of independent probes.

Second, the original theory of parallel chain formation by Chomsky (2008) was designed to account for parallel feature-checking operations, as in the case of wh-subject movement (32), which crucially does not give rise to doubling.

-

(32)

-

a.

Who saw John? (Chomsky 2008:149)

-

b.

C [T [who [v* [see John]]]]

-

c.

Whoi [C [whoj [T [whok v* [see John]]]]]

-

a.

Under Chomsky’s analysis, C bears both an edge and an Agree feature that attract the goal who sitting in Spec,v*P. The Agree feature on C is inherited by T, which causes an occurrence of who to raise to Spec,TP, while the edge feature of C causes who to raise to Spec,CP. Chomsky notes that while “there is a direct relation between whoi and whok, and between whoj and whok, [there is] none between whoi and whoj” (Chomsky 2008:149).

Thus there is an unresolved tension between Chomsky’s original formulation, which does not involve doubling, and the more recent invocations of parallel chains in the literature on predicate fronting, which do involve doubling. A parallel chains analysis in the sense of Aboh and Dyakonova (2009) (i.e., one that involves a Spell-Out condition along the lines of (31)) would predict that the occurrence of who in Spec,TP would be phonetically realized; however, as Aboh and Dyakonova (2009:1052, fn. 15) note, this contradicts the facts. In other words, it seems to be the case either that Chomsky’s analysis of wh-subject movement does not involve parallel chains or that verb doubling does not depend on parallel chains. If they both involve parallel chains, however, then we need some principled way to explain why parallel chain formation gives rise to single copy Spell-Out in one case but multiple copy Spell-Out in the other.

The current analysis will not attempt to reconcile parallel chains with remnant movement. In fact, no additional mechanisms are needed to obtain verb doubling under predicate fronting. The modification to “immediate containment” to cover head adjunction structures (29), which was independently required in order to avoid doubling of all moved heads, is sufficient to account for both the doubling of verbs and the non-doubling of complements. This is an admittedly counterintuitive result and will therefore be illustrated using a concrete (and by now familiar) derivation of predicate fronting, showing precisely how the Spell-Out conditions apply at each step.

4.2 Single vs. multiple copy pronunciation as predictions of the Spell-Out conditions

The derivation for the sentence in (33-a), involving the doubling of the verb but the single copy pronunciation of the object (in one of two places), is shown in (33-b). Note that this derivation contains the subtree already presented in (30) but with the addition of VP fronting to a left peripheral specifier (Spec,TopP) and verb movement to Top. To prevent a cluttered tree, the only instance of movement that is explicitly shown with an arrow is optional object shift to the edge of the vP phase. (This could be an intermediary landing site on the object’s path to a higher projection, such as the landing site between T and negation; not shown.)

-

(33)

4.2.1 Non-doubling of the complement

Before turning to verb doubling, we will review the predictions of the Spell-Out conditions with regard to the complement, the DP dos bukh. First, let us assume that object shift (i.e., the movement indicated by the dashed arrow) does not take place; if so, every occurrence of the DP dos bukh (#1, #2, and #4) is contained within an occurrence of the VP. The lowest VP1 is nonfinal in vP, because the highest v′ immediately contains VP2 and it also contains the set {v1,VP1}. Since VP1 is in the domain of the v phase and is nonfinal, it will be silent at PF and becomes inaccessible to further operations. Later in the derivation, VP2 raises to Spec,TopP. VP2 is nonfinal in TopP: TopP immediately contains VP3 and it also contains the set {VP2,[middle] v′}. The fronted occurrence VP3 is final because there is no syntactic object anywhere that immediately contains an occurrence of the VP and also contains the set {VP,Top′}. Consequently, transferring TopP to PF will yield only one overt occurrence of the VP (#3), including its pronounced object DP dos bukh4.

Now let’s assume that object shift (the dashed arrow) does take place prior to the fronting of the VP, i.e., the operations expected under remnant movement. Within the vP phase, the base-generated occurrence DP dos bukh1 is nonfinal: vP immediately contains DP dos bukh3 and it also contains the set {V leyen3,DP dos bukh2}. By the same reasoning, the occurrence DP dos bukh2 is also nonfinal in vP. The occurrence DP dos bukh3 is final: there is no syntactic object anywhere that immediately contains an occurrence of DP dos bukh and also contains the set {DP dos bukh,[highest] v′}. The left peripheral occurrence of the DP dos bukh4 is nonfinal: within TopP there is an object, vP, that immediately contains DP dos bukh3 and also contains the set {V leyen3, DP dos bukh2}. Transferring TopP to PF will thus result in the pronunciation of DP dos bukh3 and the silence of all other occurrences. (Again, if the DP dos bukh3 raises to an even higher projection, it will be final there and render occurrence #3 nonfinal.)

In either scenario—whether or not optional object shift occurs—the Spell-Out conditions correctly predict that the DP dos bukh will only be pronounced in one place, consistent with the expectation for remnant movement and the facts of (33-a).

4.2.2 Doubling of the verb

Having walked through the non-doubling of the complement, we now turn to the occurrences of the verb leyen ‘read.’ In order for the verb to double in (33-a), it must be the case that Top (dominating V leyen5) is final, that V leyen6 (inside the fronted VP3) is also final, and that all other occurrences of the verb are nonfinal. This is exactly what the Spell-Out conditions predict.

The externally merged V leyen1 is nonfinal in the vP phase, because there is a syntactic object (the lowest v′) that immediately contains an occurrence of <V leyen2,v> and also contains the set {V leyen1,DP dos bukh1}. As explained above, VP1 is nonfinal in vP due to the presence of VP2. At this point, the complement of the phase head v1 (i.e., the nonfinal VP1) is transferred to PF and becomes invisible for the calculation of final occurrences in subsequent phases.

The complex verbal head raises to T and to Top, forming head adjunction structures along the way. The complex v1 is nonfinal in the TopP phase: there is a syntactic object, T′, that immediately contains <v2,T> and also contains the set  . The complex T1 is similarly nonfinal, due to the presence of the identical T2 adjoined to Top. Ultimately, the only complex head that is final is Top. This is because there is no projection anywhere that immediately contains Top and also contains the set {Top,TP}. The Spell-Out conditions in (17) thus predict Top to be the only final complex head, which is exactly what would be expected under the standard assumption that only the highest head resulting from successive-cyclic movements should be pronounced.

. The complex T1 is similarly nonfinal, due to the presence of the identical T2 adjoined to Top. Ultimately, the only complex head that is final is Top. This is because there is no projection anywhere that immediately contains Top and also contains the set {Top,TP}. The Spell-Out conditions in (17) thus predict Top to be the only final complex head, which is exactly what would be expected under the standard assumption that only the highest head resulting from successive-cyclic movements should be pronounced.

Although the modification to the Spell-Out conditions (redefining “immediate containment”) was designed to capture the facts of syntactic head movement, it also predicts a final copy of the verb in the fronted VP3 in Spec,TopP. Notice that within TopP, the only syntactic objects that immediately contain an occurrence of the verb are VP3 and VP2 (and the inaccessible  ); however, these VP occurrences do not also contain the set {V leyen,DP dos bukh} because they are that set. Top′ and T′ both contain the set {V leyen3,DP dos bukh2}, but they do not immediately contain the verb or any structure of the form <V leyen,Q>. The lowest v′ immediately contains such a structure, <V leyen2,v>, but it does not also contain an accessible occurrence of the set {V leyen,DP dos bukh} (as

); however, these VP occurrences do not also contain the set {V leyen,DP dos bukh} because they are that set. Top′ and T′ both contain the set {V leyen3,DP dos bukh2}, but they do not immediately contain the verb or any structure of the form <V leyen,Q>. The lowest v′ immediately contains such a structure, <V leyen2,v>, but it does not also contain an accessible occurrence of the set {V leyen,DP dos bukh} (as  is invisible to conditions applied to the TopP phase). For these reasons, V leyen6 is final and therefore pronounced at PF.

is invisible to conditions applied to the TopP phase). For these reasons, V leyen6 is final and therefore pronounced at PF.

This protracted walk-through underscores the importance of making one’s assumptions about Spell-Out totally explicit. The original conditions from Collins and Stabler (2016) yield correct predictions about the pronunciation of occurrences under remnant phrasal movement—all within a syntactic framework that assumes the copy theory of movement. However, it became clear (as the authors acknowledge) that further modifications are required to account for the pronunciation of occurrences under syntactic head movement. Once these modifications are formally defined, it is possible to apply the Spell-Out conditions to derivations of more complex constructions, like predicate fronting. This analysis has shown that the apparent contradiction of the predicate fronting construction—the doubling of verbs and non-doubling of complements—is actually a prediction of general Spell-Out conditions, applied to a derivation in which phrasal movement and head movement both take place in the syntax.

While it is clear that the Spell-Out conditions predict the doubling of the verb and non-doubling of the complement, it is worth reiterating how that is possible. What is the intuition behind the seemingly contradictory behavior of verbs and complements? Given that the verb raises in Yiddish, why does the fronted VP seem to defy the expectations of a remnant movement analysis? Recall that we have adopted a strict version of the PIC whereby transferred structure is completely invisible for the determination of final occurrences later in the derivation. For this reason, remnant movement was shown to require a derivation in which the DP c-commands the VP at the edge of the vP phase; a different derivation in which the VP c-commands the DP is costlier in that the Spell-Out conditions predict doubling of the DP. There are (at least) two alternative derivations that would yield DP movement to a specifier position above the VP: one involving “tucking in” the VP after the DP evacuates it, and another in which remnant movement is preceded by VP smuggling. By contrast, there is no derivation in which the verb evacuates the VP via head movement but still manages to land in a position c-commanding the raised VP. This is because the VP must raise to a vP specifier, which necessarily c-commands the v head. In this way, the contrast between verb doubling and complement non-doubling relates to the difference between syntactic head movement and phrasal movement.

4.3 Morphological mismatch

One final matter that has been overlooked in the analysis thus far is the issue of morphological mismatch: although it is clear that verb doubling is predicted, the infinitival morphology realized on the fronted verb has not been addressed. One proposal comes from Abels’s (2001:13) analysis of predicate fronting in Russian and Landau’s (2006:47) analysis of the construction in Hebrew: infinitives are spelled out by default whenever there are no tense/agreement features on the verbal head. In Yiddish, this happens whenever there is a final occurrence of the verb at a position other than T, including sentences where the presence of an auxiliary or modal verb blocks movement to T. The same proposal has been made for the -en suffix spelled out in German infinitives (Biskup et al. 2011:121) and is adopted here for Yiddish.

4.4 Verb doubling and do-support

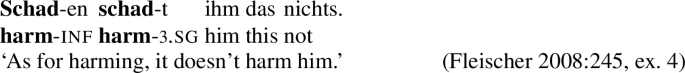

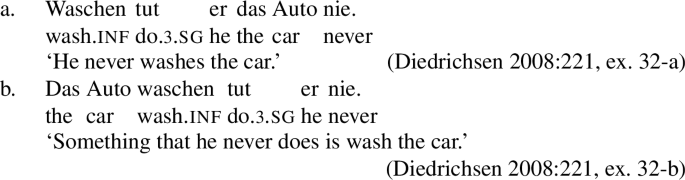

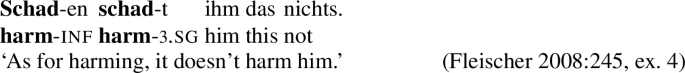

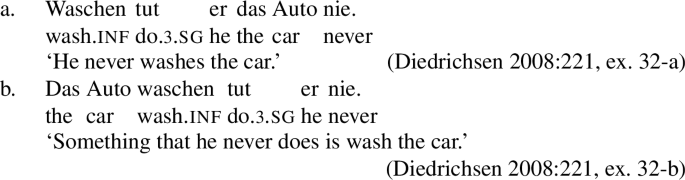

One of the predictions of the current approach to predicate fronting is that anytime a verb undergoes head movement and there is subsequent movement of the VP out of the phase in which it was base-generated, multiple occurrences of the verb should be pronounced. However, not all languages that allow for the fronting of VP topics exhibit doubling. One such language is German, which is closely related to Yiddish and exhibits the same movement operations discussed in this article, including remnant movement. In fact, there are attested examples of verb doubling from northeastern German dialects that parallel the examples from Yiddish (Fleischer 2008), as in (34) attributed to the novelist Fritz Reuter. However, most speakers apparently do not consider these sentences acceptable. Instead, the dominant strategy in German is to pronounce an infinitive in the left periphery and an occurrence of the verb tun ‘do’ with finite morphology, as in (35).

-

(34)

-

(35)

If the sentences in (35) are to be derived using the same mechanisms outlined above for Yiddish—i.e., if both involve the fronting of a VP, either (a) as a remnant category following object shift or (b) as a full category without object shift—then what accounts for the fact that German does not generally exhibit verb doubling?

Hein (2017) directly tackles this problem of cross-linguistic variability, arguing for the existence of Chain Reduction and verbal head movement as post-syntactic operations that are applied in different orders in different languages. For German sentences like those in (35), Hein assumes that the VP is fronted. Occurrences of the VP are related by chains, and the operation Chain Reduction results in the deletion of the lower VP. In German, Chain Reduction occurs prior to head movement; because the lower VP has been deleted, there is no longer a V head that can undergo post-syntactic movement to v or T or C. As a Last Resort operation, German inserts a dummy verb ‘do’ to host inflectional information.Footnote 19

For a number of reasons, Hein’s analysis of German is incompatible with the current analysis of Yiddish. The syntactic framework adopted (and extended) here specifically does not involve Chain Reduction (Collins and Stabler 2016:71). It also does not refer to post-syntactic movement or to repair mechanisms that force the pronunciation of syntactic objects not associated with lexical items. However, if we adopt Hein’s assumption that V-to-v movement is blocked in German predicate fronting, the Spell-Out conditions of (17) would correctly predict that doubling is impossible, since every occurrence of the verb would be contained within a VP, and only the fronted VP would be final.

5 Conclusions and future directions

This article highlighted an apparent contradiction between predicate fronting with doubling, which has been taken as strong evidence for the copy theory of movement, and remnant movement, which does not normally give rise to doubling. It was argued that the two can be reconciled using existing formalisms of minimalist syntax (Collins and Stabler 2016), which assume that syntactic movement involves copies rather than traces and that the same mechanisms underlying the pronunciation of nominal categories and phrases also underlie the pronunciation of verbal categories and heads. The general orientation to the problem of predicate fronting has been to assume that there are Spell-Out conditions that result in occurrences of syntactic objects being final (pronounced) or nonfinal (silent), based on their structural configurations within phases.

Only by defining these conditions explicitly is it possible to identify where they make incorrect predictions and require modification, as in the case of syntactic head movement, and ultimately whether novel constructions, like predicate fronting, are handled appropriately. This article has shown that the core asymmetry seen in Yiddish predicate fronting—that verbs double while complements do not—is actually expected under general Spell-Out conditions, combined with assumptions that the construction is derived via movement.

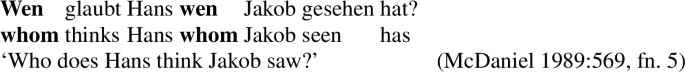

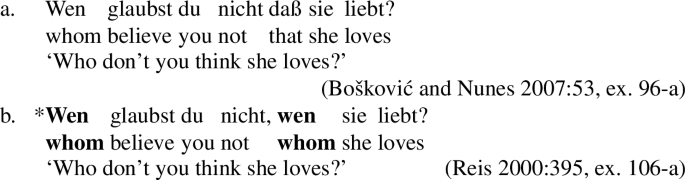

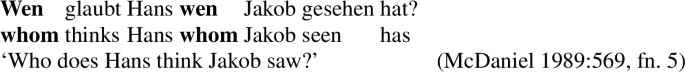

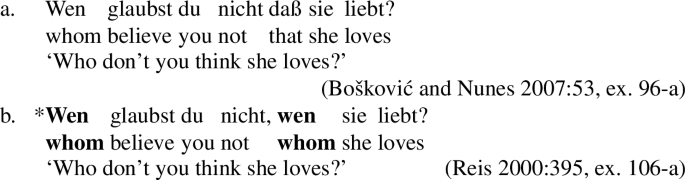

Adopting the Spell-Out conditions makes it possible to determine the occurrences of syntactic objects that are final or nonfinal. However, this does not preclude the possibility that so-called “PF repairs” may sometimes be operative, too. For example, Nunes (2004) and Bošković and Nunes (2007) have claimed that doubling can occur under morphological reanalysis, where an element undergoes movement and then fuses with an adjacent object. Consider their example of wh-copying in some varieties of German including that of the Cologne area:

-

(36)

They posit that such long distance wh-movement in German arises via head adjunction of the wh-item to C. In contrast to the more standard approach to wh-movement to Spec,CP (which does not give rise to doubling), this kind of wh-movement is subject to negative islands. The presence of a Neg head is assumed to block this movement:

-

(37)

Whereas chain linearization would not normally result in the phonetic realization of an intermediate occurrence, Bošković and Nunes (2007) claim that the intermediate occurrence of wen in (36) undergoes morphological fusion with its sister C (as in the Distributed Morphology paradigm of Halle and Marantz 1993). Once fusion occurs, this adjoined occurrence of wen is distinct and consequently no longer involved in the computation of final occurrences in the wen chain. The two phonetically realized occurrences of wen differ only in their morphology, although this difference is not overt on the surface.

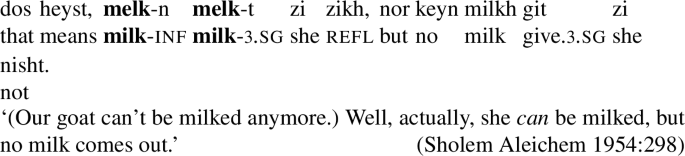

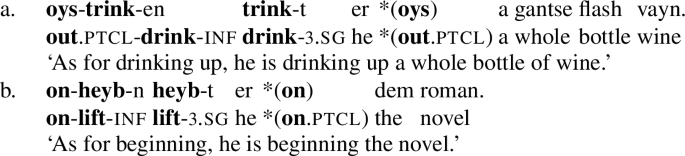

The Spell-Out conditions from Collins and Stabler (2016) rely on one rule to calculate the finality of occurrences and another rule that ensures only final occurrences are overt at PF. Of course, mechanisms that force the lexicalization of nonfinal occurrences or the silence of final occurrences—as in the Pronounce Lower Copy analysis of Bošković and Nunes (2007)—could be defined as modifications to the Spell-Out conditions. In some cases, grammatical operations might render occurrences sufficiently different from one another that they are no longer considered to be copies of the same syntactic object. In other cases, there may be semantic or even prosodic mechanisms that deterministically or probabilistically render occurrences visible or invisible at PF. In fact, some of these mechanisms could help to account for Yiddish predicate fronting involving particle verbs—novel data that await a thorough analysis. As (38) shows, predicate fronting sentences involving particle verbs can still exhibit “bare verb” doubling. (In fact, this is probably the most frequent and unmarked outcome of predicate fronting with particle verbs.) Notice that the first sentence (38-a) contains oys-trink-en out-drink-inf ‘drink up,’ a particle verb that conveys perfective aspect, while the second sentence (38-b) contains on-heyb-n on-lift-inf ‘begin,’ a particle verb that is semantically non-compositional.

-

(38)

As Yiddish grammarians Zaretski (1929:185–186) and Mark (1950, 1978) have observed, it is also acceptable to double the particle in the left periphery, as in (39). According to my consultants, the sentences in (38) and (39) are equivalent in meaning and function, although doubling the particle seems to be much less common. Note, additionally, that if the particle is doubled, the optional occurrence is in the left periphery; the lower particle must be pronounced. This suggests that the lower occurrence of the particle is always final, which would be the expectation, e.g., if the particle obligatorily raises out of the extended projection of the verb. If so, the fronted particle verb phrase should be a remnant category with respect to the particle, and it should always contain a nonfinal (silent) occurrence of the particle, as in (38) but contrary to (39).

-

(39)

There are many different approaches to the syntactic structure of particle verbs, including those that posit complex predicates involving incorporation of the particle and verb (sometimes with subsequent excorporation of the verb, e.g., to T) during syntactic derivations (Dehé et al. 2002). If particles and verbs incorporate variably in Yiddish,Footnote 20 it may be possible to derive sentences in which the particle is doubled (39) without substantial modifications to the Spell-Out conditions cited in this article, provided that incorporation yields syntactic objects that are no longer considered to be copies of lower occurrences. In any case, whenever a mechanism forcing the lexicalization of a nonfinal occurrence is required, it should be formalized as a modification to the default Spell-Out conditions assumed to be part of Universal Grammar.

Abbreviations All example sentences from Yiddish have been transliterated according to the system of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research (1999). Glosses follow Leipzig conventions. Non-standard abbreviations used in this article: expl= expletive subject; ptcl= particle.

Notes

The form glossed as an “infinitive” in (8) is actually not the irregular citation form visn know.inf but the verbal stem veys with the infinitival suffix -n. For this reason, the fronted verb has sometimes been called a “pseudoinfinitive” (Mark 1978; Waletzky 1980; Källgren and Prince 1989; Hoge 1998; Cable 2004). I refer readers to those analyses for proposals on how the pseudoinfinitive is derived, including the more peculiar tense-marked first-person and third-person forms bin-en am-inf and iz-n is-inf, which incidentally my consultants do not accept at all. Zaretski (1929), Waletzky (1980), and Hoge (1998) also provide examples of sentences where the fronted verb is the irregular infinitive zayn ‘be,’ rather than bin-en or iz-n.

One of my consultants (Herskovits) was reluctant to accept sentence (8-a) from Davis and Prince (1986). He said it is unnatural to begin a sentence with veys-n, a pseudoinfinitive, unless it is immediately followed by a conjugated form like veys-t. He did, however, accept a different sentence illustrating movement across a finite clause boundary:

-

(i)

-

(i)

While Davis and Prince (1986) assume that left-dislocated elements are base-generated in the left periphery, this is not crucial for our purposes. See Alexiadou (2006) for an overview of possible approaches, as well as Ott (2014), a more recent analysis that derives left-dislocation via movement in a biclausal structure followed by ellipsis.

To illustrate that example (11-a) is only somewhat degraded, Cable cites an unrelated English sentence involving a resumptive pronoun (his example (17)) that also receives a single question mark. Braun, who also speaks English natively, told me that the Yiddish sentence is worse than the English one.

My consultants also rejected the following sentence—a version of (1-b) suggested by a reviewer as an example of a mismatch that sounds quite natural in English:

-

(i)

-

(i)

Cable reports that mismatched predicates are also acceptable in Brazilian Portuguese. Vicente (2007:83) reports that some Spanish speakers accept sentences with mismatched genus-species predicates, as well as sentences in which the second copy of the verb appears in a coordinate structure (i.e., they accept sentences like (8-e)). Other Spanish speakers accept neither possibility, which is the case for my Yiddish consultants.

Sentence (12) is read by David Rogow, https://goo.gl/quH1Ay, 3 minutes, 30 seconds into the recording. Sentence (13) is read by Rita Karin (same link), 9 minutes, 6 seconds.

Collins and Stabler (2016) also posit a linearization algorithm (their definition 41-b) that results in specifier-head-complement order whenever sister nodes are both final. The same linearization scheme is adopted in this article.

A proposed anti-locality ban on “specifier-adjunction,” defined as *

(Grohmann 2011:264, fn. 4), is not strictly violated by the extraction of the DP from the inner to the outer specifier.

(Grohmann 2011:264, fn. 4), is not strictly violated by the extraction of the DP from the inner to the outer specifier.It has been posited that the short movement of objects and longer instances of object shift are motivated by independent reasons. For example, Johnson (1991) contends that short distance object shift is obligatory, driven by Case assignment, even if subsequent movements are optional. In the absence of compelling evidence from within Yiddish, I will need to assume that short distance object movement is optional. In a sentence like (23-a) where the verb also raises, its effect would not be visible.

One consultant (Shvaytser) indicated that the word order in (23-b) does not seem as natural as the other two examples, which are equally unmarked. However, many sentences with precisely the structure of (23-b) were readily found in both literary texts and Hasidic Yiddish blogs. Shvaytser verified that all of the attested examples I sent him were indeed perfectly acceptable.

These judgments are very strong, but intriguingly they differ from those reported by Hoge (1998), whose consultant apparently allows for the fronting of pronominal objects as long as they double. The doubling of complements is not expected to be possible under the current analysis. Previous studies of the Yiddish construction do not mention this possibility, either. Hoge (1998:92) also asserts that verb particles cannot appear in the fronted infinitive, in contrast to the data included in the conclusion section of this article and to the example sentences provided by Zaretski (1929) and Mark (1978), whom Hoge also cites.

The syntactic adjunction analysis is a dominant approach to head movement, but not the only one. For an overview of the arguments for and against this approach, as well as alternatives involving post-syntactic (PF) movement operations, see Dékány (2018).

Hein (2017:20–21) states that when the complement is pronounced below the verb ‘do’ in a German sentence like (35-b), it is because it has moved there by phrasal movement in the narrow syntax (forming a DP chain). The fronted VP is therefore a remnant category. The reason why the complement is only pronounced once, below ‘do,’ is because Chain Reduction deletes the base-generated DP in the lower VP, and since the fronted VP contains a copy of this lower link of the DP chain, Chain Reduction also deletes the DP in the fronted phrase. Hein (2017:21) mentions in a footnote that “this makes Chain Reduction a very complex operation,” and it warrants further explication.

This idea was previously suggested by Bleaman (2020:8).

References

Abels, Klaus. 2001. The predicate cleft construction in Russian. In Annual workshop on Formal Approaches to Slavic Linguistics (FASL): The Bloomington meeting 2000, eds. Steven Franks, Tracy Holloway King, and Michael Yadroff, 1–18. Ann Arbor: Michigan Slavic Publications.

Aboh, Enoch O. 2006. When verbal predicates go fronting. ZAS Papers in Linguistics 46: 21–48.

Aboh, Enoch O., and Marina Dyakonova. 2009. Predicate doubling and parallel chains. Lingua 119(7): 1035–1065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2008.11.004.

Alexiadou, Artemis. 2006. Left dislocation (including CLLD). In The Blackwell companion to syntax, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk, Vol. 2, 668–699. Malden: Blackwell Sci.

Baker, Mark C., and Chris Collins. 2006. Linkers and the internal structure of vP. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 24(2): 307–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-005-2235-1.

Bastos-Gee, Ana C. 2009. Topicalization of verbal projections in Brazilian Portuguese. In Minimalist essays on Brazilian Portuguese syntax, ed. Jairo Nunes, 161–189. Amsterdam: Benjamins. Chap. 8.

Belletti, Adriana, and Chris Collins. 2021. Introduction. In Smuggling in syntax, eds. Adriana Belletti and Chris Collins, 1–12. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197509869.003.0001. Chap. 1.

Biskup, Petr, Michael Putnam, and Laura Catharine Smith. 2011. German particle and prefix verbs at the syntax-phonology interface. Leuvense Bijdragen / Leuven Contributions in Linguistics and Philology 97: 106–135. https://doi.org/10.2143/LB.97.0.2977249.

Bleaman, Isaac L. 2020. Implicit standardization in a minority language community: Real-time syntactic change among Hasidic Yiddish writers. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 3: 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3389/frai.2020.00035.

Bondaruk, Anna. 2009. Constraints on predicate clefting in Polish. In Studies in formal Slavic phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics and information structure: Proceedings of FDSL 7, Leipzig 2007, eds. Gerhild Zybatov, Uwe Junghanns, Denisa Lenertová, and Petr Biskup, 65–78. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Bošković, Željko. 2021. On smuggling, the freezing ban, labels, and tough-constructions. In Smuggling in syntax, eds. Adriana Belletti and Chris Collins, 53–95. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197509869.003.0004. Chap. 4.

Bošković, Željko, and Jairo Nunes. 2007. The copy theory of movement: A view from PF. In The copy theory of movement, eds. Norbert Corver and Jairo Nunes, 13–74. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Burdin, Rachel Steindel. 2017. New notes on the rise-fall contour. Journal of Jewish Languages 5(2): 145–173. https://doi.org/10.1163/22134638-05021184.

Cable, Seth. 2004. Predicate clefts and base-generation: Evidence from Yiddish and Brazilian Portuguese. Ms., MIT. http://people.umass.edu/scable/papers/Yiddish-Predicate-Clefts.pdf. Last accessed 8 March 2021.

Chomsky, Noam. 1986. Barriers. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In Step by step: Essays on minimalist syntax in honor of Howard Lasnik, eds. Roger Martin, David Michaels, and Juan Uriagereka, 89–155. Cambridge: MIT Press. Chap. 3.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press. Chap. 1.

Chomsky, Noam. 2004. Beyond explanatory adequacy. In Structures and beyond: The cartography of syntactic structures, ed. Adriana Belletti, Vol. 3, 104–131. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Chap. 3.

Chomsky, Noam. 2008. On phases. In Foundational issues in linguistic theory: Essays in honor of Jean-Roger Vergnaud, eds. Robert Freidin, Carlos P. Otero, and Maria Luisa Zubizarreta, 133–166. Cambridge: MIT Press. Chap. 6.

Chomsky, Noam. 2015. Problems of projection: Extensions. In Structures, strategies and beyond: Studies in honour of Adriana Belletti, eds. Elisa Di Domenico, Cornelia Hamann, and Simona Matteini, 3–16. Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.223.01cho.

Chomsky, Noam, Ángel J. Gallego, and Dennis Ott. 2019. Generative Grammar and the Faculty of Language: Insights, questions, and challenges. Catalan Journal of Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/catjl.288.

Collins, Chris, and Edward Stabler. 2016. A formalization of minimalist syntax. Syntax 19(1): 43–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/synt.12117.

Collins, Chris, and Höskuldur Thráinsson. 1996. VP-internal structure and object shift in Icelandic. Linguistic Inquiry 27(3): 391–444.

Davis, Lori J., and Ellen F. Prince. 1986. Yiddish verb-topicalization and the notion ‘lexical integrity’. In Papers from the twenty-second regional meeting, Chicago Linguistic Society, eds. Anne M. Farley, Peter T. Farley, and Karl-Erik McCullough, 90–97. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Dehé, Nicole, Ray Jackendoff, Andrew McIntyre, and Silke Urban. 2002. Introduction. In Verb-particle explorations, eds. Nicole Dehé, Ray Jackendoff, Andrew McIntyre, and Silke Urban, 1–20. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Dékány, Éva. 2018. Approaches to head movement: A critical assessment. Glossa 3(1): 1–43. https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.316.

Diedrichsen, Elke. 2008. Where is the precore slot? Mapping the layered structure of the clause and German sentence topology. In Investigations of the syntax–semantics–pragmatics interface, ed. Jr. Robert D. Van Valin, 203–224. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Diesing, Molly. 1997. Yiddish VP order and the typology of object movement in Germanic. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 15(2): 369–427. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005778326537.

Fleischer, Jürg. 2008. Zur topikalisierenden Infinitivverdoppelung in deutschen Dialekten: Trinken trinkt er nich, aber rauchen raucht er (mit einem Exkurs zum Jiddischen). In Dialektgeographie der Zukunft: Akten des 2. Kongresses der Internationalen Gesellschaft für Dialektologie des Deutschen (IGDD) am Institut für Germanistik der Universität Wien, 20. bis 23. September 2006, eds. Peter Ernst and Franz Patocka, 243–268. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner.

Grohmann, Kleanthes K. 2011. Anti-locality: Too-close relations in grammar. In The Oxford handbook of linguistic minimalism, ed. Cedric Boeckx, 260–290. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199549368.013.0012.

Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1993. Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In The view from building 20: Essays in linguistics in honor of Sylvain Bromberger, eds. Kenneth Hale and Samuel Jay Keyser, 111–176. Cambridge: MIT Press. Chap. 3.

Hein, Johannes. 2017. Doubling and do-support in verbal fronting: Towards a typology of repair operations. Glossa 2(1): 1–36. https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.161.

Hiraiwa, Ken, and Adams Bodomo. 2008. Object-sharing as Symmetric Sharing: Predicate clefting and serial verbs in Dàgáárè. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 26(4): 795–832. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-008-9056-y.

Hoge, Kerstin. 1998. The Yiddish double verb construction. Oxford Working Papers in Linguistics, Philology and Phonetics 2: 85–97.

Johnson, Kyle. 1991. Object positions. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 9(4): 577–636. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00134751.

Källgren, Gunnel, and Ellen F. Prince. 1989. Swedish VP-topicalization and Yiddish verb-topicalization. Nordic Journal of Linguistics 12(1): 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1017/S033258650000192X.

Kandybowicz, Jason. 2008. The grammar of repetition: Nupe grammar at the syntax-phonology interface. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Kandybowicz, Jason, and Mark C. Baker. 2003. On directionality and the structure of the verb phrase: Evidence from Nupe. Syntax 6(2): 115–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9612.00058.

Koster, Jan. 1994. Predicate incorporation and the word order of Dutch. In Paths towards Universal gRammar: studies in honor of Richard S. Kayne, eds. Guglielmo Cinque, Jan Koster, Jean-Yves Pollock, Luigi Rizzi, and Raffaella Zanuttini, 255–276. Washington: Georgetown University Press.

Landau, Idan. 2006. Chain resolution in Hebrew V(P)-fronting. Syntax 9(1): 32–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9612.2006.00084.x.

Lasnik, Howard. 2001. Subjects, objects, and the EPP. In Objects and other subjects: Grammatical functions, functional categories and configurationality, eds. William D. Davies and Stanley Dubinsky, 103–121. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Mark, Yudel. 1950. Vegn dem infinitiv [The infinitive]. Yidishe Shprakh 10(1): 1–13.

Mark, Yudel. 1978. Gramatik fun der yidisher klal-shprakh [A grammar of Standard Yiddish]. New York: Congress for Jewish Culture. https://archive.org/details/MarkYudel.AGrammarOfStandardYiddish1978. Last accessed 8 March 2021.

McDaniel, Dana. 1989. Partial and multiple Wh-movement. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 7(4): 565–604. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00205158.