Abstract

The Person-Case Constraint (pcc) is a restriction on co-occurring weak pronominal direct (do) and indirect objects (io) that restricts the person value of the do. This article presents a previously unnoticed variant of the pcc found in Slovenian, where the canonical pcc operates alongside a reverse pcc, where the restriction applies to the io. This pattern is not predicted by standard syntactic approaches to the pcc (which rely on inherent asymmetries between the io and do). It is argued that the pcc (in all its forms) arises with pronouns that are inherently unspecified for a person value and need to receive it externally from a functional head via Agree. The structurally higher pronoun blocks the structurally lower pronoun from receiving a person value, giving rise to the pcc. The reverse pcc then arises due to optional do-over-io clitic movement prior to person valuation. The proposed analysis is shown to capture cross-linguistic variation regarding the pcc including the Strong/Weak pcc split, which is attributed to a variation in the structure of pronouns. The article also establishes a cross-linguistic typology of the reverse pcc, where the reverse pcc exists exclusively as an optional pattern alongside the baseline pcc pattern.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

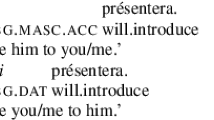

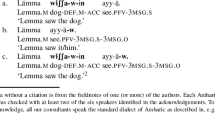

All examples are glossed using Leipzig glossing rules. Unmarked number, case, and tense are left out unless relevant, while caseless/case-syncretic pronouns are glossed according to their grammatical role.

The data in this section are from a grammaticality judgment survey performed on 29/30May 2014 through Google Forms. 42 native speakers took part in the survey composed of 24 target and 24 filler sentences. The judgments in the rest of the paper are my own and verified with 4 other speakers.

The two orders are not entirely equivalent in examples like (9). There seem to be discourse factors that influence the choice of one over the other. This will be briefly addressed in Sect. 4.1.1.

There is a contrast for ‘Weak speakers’ between 2p.do»1p.io and *1p.do»2p.io (i). I will argue in Sect. 4.1.4 that (i) is a restriction independent of the pcc (I put it aside pending the discussion below).

- (i)

- (i)

One could also translate this into cartographic functional sequences, where slots correspond to specifiers of dedicated person (PersP), number (NumP), or case (KP) projections, and can only be filled by one element. This is essentially the approach adopted by Ciucivara (2009) and Cardinaletti (2008).

Under this approach, Person-Case Constraint is a misnomer, but I still use pcc as a cover term for all syntactic person restrictions in this article due to it being so ubiquitous and established in the literature.

≫ and » are used respectively to mark asymmetric c-command and linear precedence.

Following convention, “Case” stands for abstract syntactic case.

Řezáč (2008), who gives an alternative, attributes the inaccessibility of dat goals to Agree directly to the obligatory presence of a PP dominating them, assuming PP is a phase that makes the goal invisible for Agree. This change does not affect the incorrect predictions regarding the Slovenian facts.

Note that the French surface clitic order in (17) does not reflect their position in (18). It is crucial for Béjar and Řezáč (2003) (and for my analysis in Sect. 4) that the configuration is io≫do at the stage when v probes. See Sect. 6 for a discussion of the relation between clitic order and the pcc cross-linguistically.

Note that for Béjar and Řezáč (2003) all dat arguments (including clitics) are PPs. The analysis to be proposed in Sect. 4 does not require this assumption. In fact, there is a case to be made that at least dat clitics cannot be PPs. As Abels (2003a,b) shows, in non-P-stranding languages (like Slovenian or French) clitics cannot be complements in PPs as a result of two conflicting requirements: (i) clitics in PPs must extract to a position outside PP, and (ii) PPs block complement extraction in non-P-stranding languages. This can also explain why in French prepositional ditransitives the io is never a clitic (Perlmutter 1971; Kayne 1975).

Anagnostopoulou (2003, 2005) proposes that io and do inherently carry different sets of φ-features: io only has [π], while do only has [#] if 3p or has both [#] and [π] if 1/2p. Adger and Harbour (2007), similarly, propose that the io must always have a [participant] feature, even if 3p—in contrast to the do. In both approaches, the pcc arises due to a Case-checking asymmetry that such differences yield in a doc. In simplified terms: in the presence of an io a 3p.do can check Case while a 1/2p.do cannot.

A similar principle is employed by Nevins (2007, 2011), who proposes that both Strong and Weak pcc arise due to constraints on MA. The idea is that what counts as a conflicting specification, not the option of MA itself, is parameterized. If both goals have non-conflicting [π] values, the probe Agrees with them both, triggering clitic-doubling. However, if the two goals have conflicting [π] values, Agree is impossible with the lower one, yielding the pcc. Crucially, Agree never takes place with 3p goals in his system. This creates an issue though, as clitic-doubling must also take place with 3p objects. Thus, 3p clitics must be assumed to surface even when Agree fails, but this is at odds with Preminger’s (2009) insight that failed Agree always results in the lack of clitic-doubling, never in “default” clitic-doubling.

There is another link between the pcc and binding, noted by Ormazabal and Romero (2007) (attributing it to Roca 1992): in some languages animate do clitics cannot be bound in the presence of an io clitic. Bhatt and Šimík (2009) also note for Slovenian that with the do»io clitic order, the binding ban applies to the io clitic (parallel to the reverse pcc). I take the constraint as additional support for analyzing the pcc in terms of Kratzer (2009) (but see Charnavel and Mateu 2015 for an alternative view).

Number restrictions in docs only seem to arise due to language specific morphological factors (Ciucivara and Nevins 2008; Nevins 2011), whereas the pcc arises even with morphologically inert null markers (Albizu 1997b; Ormazabal and Romero 2007) and is insensitive to morphological factors like syncretism (Adger and Harbour 2007). I do not, however, exclude the possibility of pcc-like restrictions being sensitive to animacy and definiteness (see Ormazabal and Romero 2007). If Richards (2008) is correct, these notions are manifestations of [π] features and such restrictions should then also follow from my proposal.

The difference in the valued/unvalued status between [π] and [Γ] can also be related to the curious absence of pcc effects with reflexive clitics in Bulgarian (Rivero 2004) and Slovenian (Stegovec 2016a). Unlike the reflexive clitics in languages where these do yield pcc effects (Anagnostopoulou 2003, 2005), the reflexive clitics in Bulgarian and Slovenian never show number/gender contrasts—suggesting the lack of [Γ] features, but do pattern morphologically with 1/2p pronouns—suggesting the presence of [π] features. Due to the lack of [iΓ], these clitics are then not eligible goals for the [uΓ] probe on v. A reflexive io then does not block Agree between v and a non-reflexive do, which can then be valued 1/2p parasitically on [Γ], explaining why the pcc is voided in such cases in Bulgarian and Slovenian. In Slovenian, this holds for both Strong and Weak pcc, as well as the reverse pcc with reflexive dos (Stegovec 2016a).

Note that although do’s unvalued [iπ] is here technically an active probe without a matching goal in its probing domain, the last resort default value allows the derivation to proceed, in line with Preminger (2014). As we will see later, different displacement possibilities for the do may change this outcome.

I do not argue against Multiple Agree as a possible operation, I simply show that it is not needed to derive the Weak pcc (but see Haegeman and Lohndal 2010 for explicit arguments against its existence).

Although the checking operation predates Agree, they can be equated for present purposes. What is important is that they are both operations that occur between matching feature sets; the issue of what happens to uninterpretable features after taking part in a checking or Agree operation arises with both.

A reviewer asks what prevents

in Strong pcc derivations in Slovenian (cf. (34,36)) from moving across

in Strong pcc derivations in Slovenian (cf. (34,36)) from moving across  to SpecvP and be [π]-valued there. Recall that object reordering can occur in Slovenian before v enters the derivation, so either io or do can be closest to v and be [π]-valued without having to move to SpecvP. It is possible that the option of early object reordering (below v) blocks any derivations with late object reordering—like the one suggested by the reviewer. Another possibility is that with the Strong pcc, where Maximize Agree forces [π] to be valued parasitically to [Γ], the immediate valuation of all unvalued features on both v and

to SpecvP and be [π]-valued there. Recall that object reordering can occur in Slovenian before v enters the derivation, so either io or do can be closest to v and be [π]-valued without having to move to SpecvP. It is possible that the option of early object reordering (below v) blocks any derivations with late object reordering—like the one suggested by the reviewer. Another possibility is that with the Strong pcc, where Maximize Agree forces [π] to be valued parasitically to [Γ], the immediate valuation of all unvalued features on both v and  always enforces the immediate deletion of [uπ] on v (cf. (43)), thus leaving the

always enforces the immediate deletion of [uπ] on v (cf. (43)), thus leaving the  without a source of valued [π] even if it moved to SpecvP. As it does not matter for the present discussion which of the options is correct, I leave teasing them apart for future work.

without a source of valued [π] even if it moved to SpecvP. As it does not matter for the present discussion which of the options is correct, I leave teasing them apart for future work.Due to the optionality of [uπ] deletion, there are really two derivations that yield 3p≫3p: one parallel to (i)—where [uπ] is not deleted after Agree with

, and one parallel to (iii)—where it is deleted. Since valued and default 3p are equivalent in the [π] system I adopt, both come out the same.

, and one parallel to (iii)—where it is deleted. Since valued and default 3p are equivalent in the [π] system I adopt, both come out the same.Interestingly, some speakers I consulted actually judge do»io clitic orders as slightly improved when the io»do clitic order would result in a banned combination such as *2p.io»1p.do.

I do not, however, exclude the possibility that differences in the timing or locus of auth-valuation could potentially arise due to language-specific factors and give rise to more fine-grained person restrictions like the one we saw with BCS above (see also Nevins 2007 for more similar restrictions). This is something I leave as a possibility to explore in future work; but see Franks (2016) for an analysis of the BCS person restriction based on an earlier version of the analysis of the pcc presented here.

Charnavel and Mateu (2015) in fact argue that the pcc itself should be reduced to this restriction—the io clitic intervenes between the operator and the 1/2p clitic. But this excludes both the Weak pcc and the reverse pcc—the patterns which show that the pcc should not simply be reduced to logophoric licensing.

Anagnostopoulou (2003, 2005) alternatively argues that in these cases strong pronouns simply do not check their φ-features against v, as they do not enter into a Move/Agree relation with v. This means that Case-checking must not be a requirement for strong pronouns (Anagnostopoulou 2003:316–321). While this does capture the facts, it is difficult to see why strong pronouns should be exempt from Case-checking, especially with cases like Slovenian where clitic and strong forms both express the same case contrasts.

One potential exception to this generalization is Icelandic, where strong nom object pronouns are restricted to 3p in the presence of a dat subject (Taraldsen 1995). However, as Schütze (2003) argues, there is evidence that this actually results from the ineffability of the agreement marker itself. I discuss the relevance of the difference between the pcc and this Icelandic person restriction in Stegovec (2016a).

The resulting object is not unlike what was assumed about INFL prior to Pollock (1989), namely that it was a bundle of T and AGR. See also Bobaljik and Thráinsson (1998) regarding the parameterization of the INFL split, which is similar to what I am proposing regarding the clitic/weak pronoun split.

A reviewer suggests English as a potential counterexample, as it appears to have the Strong pcc (Richards 2008). But it is not entirely clear that English deficient pronouns are not clitics. As Bošković (2004a) points out, at least pronouns that license quantifier float cannot be coordinated and must be unstressed (‘*Mary hates you, him, and her all’; ‘*Mary hates THEM all’ vs. ‘Mary hates them all’), which are properties associated with clitics (see also Lasnik 1999 regarding clitic pronouns in English).

See Sheppard and Golden (2002) regarding clitic placement in Slovenian imperatives. I noted above that Slovenian is losing a rigid 2nd position requirement, occasionally allowing clitics in the 1st position, but as Sheppard and Golden observe, this is not true of imperatives, which never allow 1st position clitics.

The editor asks if the lack of pcc effects in imperatives could be tied to the perspective shift effects discussed briefly in Sect. 4.1.4. This is an attractive idea, given that imperatives have been argued to shift the perspective to the addressee, just like questions (Speas and Tenny 2003), and we saw in Sect. 4.1.4 that Slovenian questions differ from declaratives in terms of possible clitic combinations. However, imperatives and questions behave differently here: recall that the order of 1p and 2p clitics is more constrained in questions than outside of them and that the pcc effect is actually observed in questions. Furthermore, there is independent evidence that imperatives actually pattern with declaratives, not questions, in terms of perspective encoding. I discuss the relevant semantic and syntactic facts in Stegovec (2017a, 2018).

The pcc effect is perceived as weaker than in declaratives here, although it is stronger again with 3p.f clitics—it is unclear why this is so. A similar weakening of the pcc is also observed in Greek imperatives with the do»io clitic order (see (59b) below and Bonet 1991, Mavrogiorgos 2010 for discussion).

Notice that in order for do-over-io movement to even occur, it cannot be preceded by head-adjunction of the do clitic to V. Because of this I assume here and below that in such cases head-adjoining “as soon as possible” means head-adjoining as soon as possible after do-over-io movement has taken place.

Nothing hinges on the identity of the head(s) between v and T here, but there are many arguments in the literature for projections between vP and TP; e.g.: from verb movement (Belletti 1990; Cinque 1999; Stjepanović 1999), subject positions (Bobaljik and Jonas 1996), and quantifier float (Bošković 2004a).

Tucking in is only relevant when both elements are head-moving or XP-moving: as a SpecKP target always precedes an Ktarget, if one element head-moves to Kand the other element XP-moves to SpecKP, the latter will always precede the head-moved element regardless of the order in which they move.

The editor asks why a clitic may sometimes cross another one outside vP (e.g. in (68a)) without contradicting a previous linearization. In all such cases (but not in (74d)) the clitic order established within vP is always reestablished with the final positions of the clitics in CP. I therefore assume that linearization only cares about the topmost copies of moving elements within a phase, which can be seen as a natural result of combining the approach to copy pronunciation assumed above with phase-based derivations.

As far as I could gather, Werner (1999) uses ‘??’ to mark unacceptability in (77b) because the speakers he consulted tend to replace the weak pronoun forms with strong ones to ameliorate the construction.

From the data provided by Werner (1999) it is impossible to discern whether the restriction is Strong or Weak or some other type of pcc. Czech conforms to Weak pcc with an additional 1p»2p restriction.

A similar case is found in (standard) German, where the Weak pcc arises with weak object pronoun pairs in the Wackernagel position of embedded clauses. Anagnostopoulou (2008:29) notes that while the base order there is generally do»io, speakers may resort to an io»do order to void the pcc effect. Also, when the io and do are both 1/2p person, both do»io and io»do orders are possible.

A small number of the consulted Slovenian speakers also had judgments similar to (81).

I have identified the typological gap as part of an ongoing broad cross-linguistic survey of pcc effects spanning so far 101 languages from 24 families and 3 isolates (Stegovec in preparation b). The survey also reveals the reverse pcc to be quite rare in general; I was able to identify it only in the languages discussed above and a few others. The preliminary findings of the survey, based on a smaller number of languages, were presented in Stegovec (2017b).

The lack of pcc effects here could be due to ios always being strong pronouns in PPs and thus in prepositional ditransitives (see fn. 13), or because Ps may, just like v, bear valued [π] features.

References

Abels, Klaus. 2003a. *[P clitic]!—Why? In Conference on Formal Description of Slavic Languages (FDSL) 4, Potsdam 2001, eds. Peter Kosta, Joanna Blaszczak, Jens Frasek, Ljudmila Geist, and Marzena Zygis, 443–460. Frankfurt am Main: Linguistik International, Peter Lang.

Abels, Klaus. 2003b. Successive cyclicity, anti-locality, and adposition stranding. PhD diss., UConn.

Adger, David, and Daniel Harbour. 2007. Syntax and syncretism of the Person Case Constraint. Syntax 10: 2–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9612.2007.00095.x.

Aissen, Judith L. 1987. Tzotzil clause structure. Dordrecht: D. Reidel.

Albizu, Pablo. 1997a. Generalized person-case constraint: A case for a syntax driven inflectional morphology. In Theoretical issues on the morphology-syntax interface, eds. Myriam Utribe-Extebarria and Amaya Mendikoetxea, 1–33. Donostia: UPV/EHU.

Albizu, Pablo. 1997b. The syntax of person agreement. PhD diss., USC, Los Angeles.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 1999. Person Restrictions. Paper presented at the 21st GLOW Colloquium, ZAS-Berlin, March 29, 1999. [Glow Newsletter 42: 12–13].

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 2003. The syntax of ditransitives: Evidence from clitics. Studies in generative grammar. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 2005. Strong and weak person restrictions: A feature checking analysis. In Clitic and affix combinations, eds. Lorie Heggie and Francisco Ordóñez, 199–235. Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.74.08ana.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 2008. Notes on the Person-Case Constraint in Germanic. In Agreement restrictions, eds. Roberta D’Alessandro, Susann Fischer, and Gunnar H. Hrafnbjargarson, 15–47. Berlin: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110207835.15.

Baker, Mark C. 2008a. The macroparameter in a microparametric world. In The limits of variation, ed. Theresa Biberauer. Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.132.16bak.

Baker, Mark C. 2008b. The syntax of agreement and concord. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Béjar, Susana, and Milan Řezáč. 2003. Person licensing and the derivation of PCC effects. In Romance linguistics: Theory and acquisition, eds. Ana T. Perez-Leroux and Yves Roberge, 49–62. Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.244.07bej.

Béjar, Susana, and Milan Řezáč. 2009. Cyclic Agree. Linguistic Inquiry 40: 35–73. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling.2009.40.1.35.

Belletti, Adriana. 1990. Generalized verb movement. Turin: Rosenberg and Sellier.

Bhatt, Rajesh, and Radek Šimík. 2009. Variable binding and the Person-Case Constraint. Talk given at Israel Association for Theoretical Linguistics (IATL) 25. Ben-Gurion University of the Negev.

Bliss, Heather. 2013. The Blackfoot configurationality conspiracy. PhD diss., University of British Columbia.

Bobaljik, Jonathan. 1995. Morphosyntax: The syntax of verbal inflection. PhD diss., MIT.

Bobaljik, Jonathan, and Dianne Jonas. 1996. Subject positions and the roles of TP. Linguistic Inquiry 27: 195–236.

Bobaljik, Jonathan, and Höskuldur Thráinsson. 1998. Two heads aren’t always better than one. Syntax 1 (1): 37–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9612.00003.

Bonet, Eulalia. 1991. Morphology after syntax: Pronominal clitics in Romance languages. PhD diss., MIT.

Bonet, Eulalia. 1994. The Person-Case Constraint: A morphological approach. MIT Working papers in Linguistics 22: The Morphology-Syntax Connection: 33–52.

Borer, Hagit. 1984. Parametric syntax: Case studies in Semitic and Romance languages. Dordrecht: Foris.

Bošković, Željko. 1999. On multiple feature checking: Multiple Wh-fronting and multiple head movement. In Working minimalism, eds. Samuel David Epstein and Norbert Hornstein, 159–187. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bošković, Željko. 2001. On the nature of the syntax-phonology interface: Cliticization and related phenomena. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Bošković, Željko. 2004a. Be careful where you float your quentifiers. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 22 (4): 681–742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-004-2541-z.

Bošković, Željko. 2004b. On the clitic switch in Greek imperatives. In Balkan syntax and semantics, ed. Olga Mišeska Tomić, 269–291. Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.67.14bos.

Bošković, Željko. 2007. On the locality and motivation of Move and Agree: An even more minimal theory. Linguistic Inquiry 38 (4): 589–644. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling.2007.38.4.589.

Bošković, Željko. 2009. Unifying first and last conjunct agreement. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 27: 455–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-009-9072-6.

Bošković, Željko. 2011a. On unvalued uninterpretable features. In Northeast Linguistic Society (NELS) 39, eds. Suzi Lima, Kevin Mullin, and Brian Smith, 109–120. Amherst: GLSA.

Bošković, Željko. 2011b. Rescue by PF deletion, traces as (non)interveners, and the That-trace effect. Linguistic Inquiry 42: 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1162/LING_a_00027.

Bošković, Željko, and Jairo Nunes. 2007. The copy theory of movement: A view from PF. In The copy theory of movement, eds. Norbert Corver and Jairo Nunes, 13–74. Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.107.03bos.

Cardinaletti, Anna. 2008. On different types of clitic clusters. In The Bantu–Romance connection, eds. Cécile De Cat and Katherine Demuth, 41–82. Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.131.06car.

Cardinaletti, Anna, and Michal Starke. 1994. The typology of structural deficiency: On the three grammatical classes. Working Papers in Linguistics 4 (2): 41–109. University of Venice.

Cardinaletti, Anna, and Michal Starke. 1999. The typology of structural deficiency: A case study of the three classes of pronouns. In Clitics in the languages of Europe, 145–233. New York: Mouton de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022226703282293.

Charnavel, Isabelle, and Victoria Mateu. 2015. The clitic binding restriction revisited: Evidence for antilogophoricity. The Linguistic Review 32 (4): 671–701. https://doi.org/10.1515/tlr-2015-0007.

Chomsky, Noam. 1957. Syntactic structures. The Hague: Mouton.

Chomsky, Noam. 1986. Knowledge of language, its nature, origin, and use. New York: Praeger.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In Step by step: Essays on minimalism in honor of Howard Lasnik, eds. Roger Martin, David Michaels, and Juan Uriagereka, 89–155. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2013. Problems of projection. Lingua 130: 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2012.12.003.

Chomsky, Noam. 2015. Problems of projection: Extensions. In Structures, strategies and beyond: Studies in honor of Adriana Belletti, eds. Elisa Di Domenico, Cornelia Hamann, and Simona Matteini, 1–16. Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.223.01cho.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1999. Adverbs and functional heads: A cross-linguistic perspective. Oxford: Oxford Studies in Comparative Syntax.

Ciucivara, Oana Săvescu. 2009. A syntactic analysis of pronominal clitic clusters in Romance: The view from Romanian. PhD diss., NYU.

Ciucivara, Oana Săvescu, and Andrew Nevins. 2008. An apparent Number Case Constraint in Romanian: The role of syncretism. In 38th Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages (LSRL), eds. Karlos Arregi, Zsuzsanna Fagyal, and Silvina Montrul, 185–203. Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.313.17nev.

Collins, Chris. 1995. Toward a theory of optimal derivation. MIT Working papers in Linguistics 27: 65–104.

Comrie, Bernard. 1979. The animacy hierarchy in Chukchee. In The elements: A parasession on linguistic units and levels, eds. Paul R. Clyne, William F. Hanks, and Carol L. Hofbauer, 322–329. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Demuth, Katherine, and Jeffrey Gruber. 1995. Constraining XP-sequences. Niger-Congo Syntax & Semantics 6: 3–30.

Duranti, Alessandro. 1979. Object clitic pronouns and the topicality hierarchy. Studies in African Linguistics 10: 31–45.

Erschler, David. 2014. Person Case Constraints beyond the Dative and Accusative: Evidence from Ossetic. Ms. Max Planck Institut/Tübinger Zentrum für Linguistik.

Fehrmann, Dorothee, Uwe Junghanns, and Denisa Lenertová. 2010. Two reflexive markers in Slavic. Russian Linguistics 34 (3): 203–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-010-9062-7.

Fox, Danny, and David Pesetsky. 2005. Cyclic linearization of syntactic structure. Theoretical Linguistics 31: 235–262. https://doi.org/10.1515/thli.2005.31.1-2.1.

Franks, Steven. 1995. Parameters of Slavic morphosyntax. New York: OUP.

Franks, Steven. 1998/2010. Clitics in Slavic. Paper presented at the Comparative Slavic Morphosyntax Workshop, Spencer, Indiana. [Updated version published on-line in Glossos 10: Contemporary Issues in Slavic Linguistics].

Franks, Steven. 2016. Clitics are/become minimal(ist). In Formal studies in Slovenian syntax: In honor of Janez Orešnik, eds. Lanko Marušič and Rok Žaucer, 91–128. Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.236.05fra.

Freidin, Robert, and Rex A. Sprouse. 1991. Lexical case phenomena. In Principles and parameters in comparative grammar, ed. Robert Freidin, 392–416. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Georgala, Effi. 2011. Applicatives in their structural and thematic function: A minimalist account of multitransitivity. PhD diss., Cornell Unversity.

Haegeman, Liliane, and Terje Lohndal. 2010. Negative concord and (Multiple) Agree: A case study of West Flemish. Linguistic Inquiry 41 (2): 181–211. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling.2010.41.2.181.

Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1993. Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In The view from Building 20, eds. Kenneth Locke Hale and Samuel Jay Keyser, 111–176. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Harley, Heidi, and Elizabeth Ritter. 2002. Person and number in pronouns: A feature-geometric analysis. Language 78 (3): 482–526. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2002.0158.

Hiraiwa, Ken. 2001. Multiple Agree and the defective intervention constraint in Japanese. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 40: 67–80.

Hiraiwa, Ken. 2004. Dimensions of symmetry in syntax: Agreement and causal architecture. PhD diss., MIT.

Joseph, Brian D., and Irene Philippaki-Warburton. 1987. Modern Greek. London: Croom Helm.

Kalin, Laura, and Coppe van Urk. 2015. Aspect splits without ergativity: Agreement asymmetries in Neo-Aramaic. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 33 (2): 659–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-014-9262-8.

Kaufmann, Magdalena. 2012. Interpreting imperatives. Berlin: Springer.

Kayne, Richard S. 1975. French syntax. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kayne, Richard S. 2000. Parameter and universals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kratzer, Angelika. 2009. Making a pronoun: Fake indexicals as windows into the properties of pronouns. Linguistic Inquiry 40 (2): 187–237. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling.2009.40.2.187.

Kuno, Susumu. 1987. Functional syntax: Anaphora, discourse and empathy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lamoureaux, Siri van Dorn. 2004. Applicative constructions in Maasai. MA thesis, University of Oregon.

Lasnik, Howard. 1981. Restricting the theory of transformations: A case study. In Explanations in linguistics, eds. Norbert Hornstein and David Lightfoot, 152–173. London: Longman.

Lasnik, Howard. 1995. Verbal morphology: Syntactic structures meets the minimalist program. In Evolution and revolution in linguistic theory: Essays in honor of Carlos Otero, eds. Héctor Campos and Paula Kempchinsky, 251–275. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Lasnik, Howard. 1999. Chains of arguments. In Working minimalism, eds. Samuel Epstein and Norbert Hornstein, 189–215. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Marantz, Alec. 1993. Implications of asymmetries in double object constructions. In Theoretical aspects of Bantu grammar 1, ed. Sam A. Mchombo, 113–151. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Marvin, Tatjana, and Adrian Stegovec. 2012. On the syntax of ditransitive sentences in Slovenian. Acta Linguistica Hungarica 59 (1–2): 177–203. https://doi.org/10.1556/ALing.59.2012.1-2.8.

Mavrogiorgos, Marios. 2010. Clitics in Greek: A minimalist account of proclisis and enclisis. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

McGinnis, Martha Jo. 2005. On markedness asymmetries in person and number. Language 81 (3): 699–718. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2005.0141.

Mel’čuk, Igor. 1988. Dependency syntax: Theory and practice. Albany: SUNY Press.

Messick, Troy. 2016. The morphosyntax of self-ascription: A cross-linguistic study. PhD diss., University of Connecticut.

Migdalski, Krzysztof. 2006. The syntax of compound tenses in Slavic. PhD diss., Tilburg University.

Miyoshi, Nobuhiro. 2002. Negative Imperatives and PF merger. Ms. UConn Storrs.

Montalbetti, Mario. 1984. After binding: On the interpretation of pronouns. PhD diss., MIT.

Moore, John, and David M. Perlmutter. 2000. What does it take to be a dative subject. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 18 (2): 373–416. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006451714195.

Moskal, Beata. 2015. Domains at the border: Between morphology and phonology. PhD diss., UConn.

Nevins, Andrew. 2007. The representation of third person and its consequences for person-case effects. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 25 (2): 273–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-006-9017-2.

Nevins, Andrew. 2011. Multiple Agree with clitics: Person complementarity vs. omnivorous number. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 29 (4): 939–971. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-011-9150-4.

Nicol, Fabrice. 2005. Romance clitic clusters: On diachronic changes and cross-linguistic contrasts. In Clitic and affix combinations, eds. Lorie Heggie and Francisco Ordóñez, 141–199. Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.74.07nic.

Ormazabal, Javier, and Juan Romero. 2007. The object agreement constraint. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 25: 315–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-006-9010-9.

Pearson, Hazel. 2012. The sense of self: Topics in the semantics of De Se expressions. PhD diss., Harvard.

Perlmutter, David. 1971. Deep and surface structure constraints in syntax. Transatlantic series in linguistics. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Perlmutter, David M. 1982. Syntactic representation, syntactic levels, and the notion of subject. In The nature of syntactic representation, eds. Pauline Jacobson and Geoffrey K. Pullum, 283–340. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-7707-5_8.

Pesetsky, David, and Esther Torrego. 2007. The syntax of valuation and the interpretability of features. In Phrasal and clausal architecture: Syntactic derivation and interpretation. In honor of Joseph E. Emonds., eds. Simin Karimi, Vida Samiian, and Wendy K. Wilkins, 262–294. Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.101.14pes.

Pollock, Jean-Yves. 1989. Verb movement, universal grammar and the structure of IP. Linguistic Inquiry 20 (3): 365–424.

Preminger, Omer. 2009. Breaking agreement: Distinguishing agreement and clitic doubling by their failures. Linguistic Inquiry 40 (4): 619–666. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling.2009.40.4.619.

Preminger, Omer. 2014. Agreement and its failures. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Pylkkänen, Liina. 2002. Introducing arguments. PhD diss., MIT.

Pylkkänen, Liina. 2008. Introducing arguments. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Richards, Marc. 2008. Defective Agree, case alternations, and the prominence of person. In Scales, eds. Marc Richards and Andrej L. Malchukov, 137–161. Leipzig: Universität Leipzig.

Richards, Norvin. 1997. What moves where when in which language? PhD diss., MIT.

Richards, Norvin. 2001. Movement in language: Interactions and architectures. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Riedel, Kristina. 2009. The syntax of object marking in Sambaa: A comparative Bantu perspective. PhD diss., Universiteit Leiden.

Rivero, María Luisa. 2004. Spanish quirky subjects, person restrictions, and the Person-Case Constraint. Linguistic Inquiry 35 (3): 494–502. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling.2004.35.3.494.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1990. On the anaphor-agreement effect. Rivista di Linguistica 2: 27–42.

Roca, Francesc. 1992. On the licensing of pronominal clitics. The properties of object clitics in Spanish and Catalan. Master’s thesis, Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona.

Rosen, Carol. 1990. Rethinking Southern Tiwa: The geometry of a triple-agreement language. Language 66 (4): 669–713.

Runić, Jelena. 2013. The Person-Case Constraint: A morphological consensus. Poster presented at the 87th Meeting of the Linguistic Society of America (LSA).

Saito, Mamoru. 2016. (A) Case for labeling: Labeling in languages without ϕ-feature agreement. The Linguistic Review 33 (1). https://doi.org/10.1515/tlr-2015-0017.

Schütze, Carson T. 2003. Syncretism and double agreement with Icelandic nominative objects. In Grammar in focus: Festschrift for Christer Platzack, eds. Lars-Olof Delsing, Cecilia Falk, Gunlög Josefsson, and Halldór Á. Sigurðsson, Vol. 2, 295–303. Lund: Department of Scandinavian Languages.

Sheppard, Milena Milojević, and Marija Golden. 2002. (Negative) imperatives in Slovene. In Modality and its interaction with the verbal system, eds. Sjef Barbiers, Frits Beukema, and Wim van der Wurff, 245–260. Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.47.12mil.

Smith, Peter W. 2015. Feature mismatches: Consequences for syntax, morphology and semantics. PhD diss., UConn.

Speas, Peggy, and Carol Tenny. 2003. Configurational properties of point of view roles. In Asymmetry in grammar, ed. Anna Maria Di Sciulo, 315–343. Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.57.15spe.

Stegovec, Adrian. 2016a. Not two sides of one coin: Clitic person restrictions and Icelandic quirky agreement. In Formal studies in Slovenian syntax: In honor of Janez Orešnik, eds. Franc Lanko Marušič and Rok Žaucer, 283–312. Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.236.12ste.

Stegovec, Adrian. 2016b. What we aren’t given: The influence of selection on ditransitive passives in Slovenian. Talk given at Formal Approaches to Slavic Linguistics (FASL) 25, Cornell.

Stegovec, Adrian. 2017a. !? (Where’s the ban on imperative questions?). In Semantic and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 27, eds. Dan Burgdorf, Jacob Collard, Sireemas Maspong, and Brynhildur Stefánsdóttir, 153–172. Ithaca: Cornell. https://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v27i0.4140.

Stegovec, Adrian. 2017b. Between you and me: Two crosslinguistic generalizations on person restrictions. In 34th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL), eds. Aaron Kaplan, Abby Kaplan, Miranda K. McCarvel, and Edward J. Rubin, 498–508. Somerville: Cascadilla Press.

Stegovec, Adrian. 2018. Perspectival control and obviation in directive clauses. Natural Language Semantics, in press.

Stegovec, Adrian. in preparation a. Ditransitives spill the beans: Insights from Slovenian ditransitive passives and idioms.

Stegovec, Adrian. in preparation b. Why only π? the exceptionality of person in syntax and its interfaces. PhD diss., University of Connecticut.

Stjepanović, Sandra. 1999. What do second-position cliticization, scrambling and multiple wh-fronting have in common? PhD diss., UConn.

Sturgeon, Anne, Boris Harizanov, Maria Polinsky, Ekaterina Kravtchenko, Carlos Gómez Gallo, Lucie Medová, and Václav Koula. 2012. Revisiting the Person Case Constraint in Czech. In Formal Approaches to Slavic Linguistics(FASL) 19, eds. John Bailyn, Ewan Dunbar, Yakov Kronrod, and Chris LaTerza, 116–130. Ann Arbor: Michigan Slavic Publications.

Szucsich, Luka. 2008. Evidenz für syntaktische Nullen im Burgenland-Kroatischen, Polnischen, Russischen und Slovenischen. Merkmalsausstattung, Merkmalshierarchien und morphologische Defaults. Zeitschrift für Slavistic 53 (2): 160–177. https://doi.org/10.1524/slaw.2008.0012.

Taraldsen, Tarald. 1995. On agreement and nominative objects in Icelandic. In Studies in comparative Germanic syntax, eds. Hubert Haider, Susan Olsen, and Sten Vikner, 307–327. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Terzi, Arhonto. 1999. Clitic combinations, their hosts and their ordering. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 17: 85–121. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006075626603.

Ura, Hiroyuki. 1996. Multiple feature checking: A theory of grammatical function splitting. PhD diss., MIT.

Řezáč, Milan. 2008. Phi-agree and Theta-related Case. In Phi theory, eds. Daniel Harbour, David Adger, and Susana Béjar, 83–129. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Řezáč, Milan. 2011. Phi-features and the modular architecture of language. Dordrecht: Springer.

Řezáč, Milan. 2004. The EPP in Breton: An uninterpretable categorial feature. In Triggers, eds. Henk van Riemsdijk and Anne Breitbarth, 451–492. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Walkow, Martin. 2012. Goals, big and small. PhD diss., UMass.

Warburton, Irene. 1977. Modern Greek clitic pronouns and the ‘surface structure constraint’ hypothesis. Journal of Linguistics 13: 259–281.

Wechsler, Stephen. 2017. Self-ascription in conjunct-disjunct systems. In Egophoricity, eds. Simeon Floyd, Elisabeth Norcliffe, and Lila San Roque, 471–492. Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/tsl.118.15wec.

Werner, Ingegerd. 1999. Die Personalpronomen im Zürichdeutschen. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

Woolford, Ellen. 1999. More on the anaphor agreement effect. Linguistic Inquiry 30 (2): 257–287. https://doi.org/10.1162/002438999554057.

Yip, Moira, Joan Maling, and Ray Jackendoff. 1987. Case in tiers. Language 63: 217–250.

Zanuttini, Rafaela, Miok Pak, and Paul Portner. 2012. A syntactic analysis of interpretive restrictions on imperative, promissive, and exhortative subjects. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 30: 1231–1274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-012-9176-2.

Acknowledgements

I thank Amy Rose Deal, Jonathan Bobaljik, Željko Bošković, Paula Fenger, Steven Franks, Laura Kalin, Ivona Kučerova, Troy Messick, Andrew Nevins, Jairo Nunes, Roumyana Pancheva, Omer Preminger, Mamoru Saito, Koji Shimamura, Susi Wurmbrand, and Michelle Yuan for their comments, suggestions, and valuable discussion. I would also like to thank for their feedback the audiences at the UConn LingLunch (October 2014), NELS 45 (MIT), WCCFL 33 (SFU), FASL 24 (NYU), ECO-5 (Harvard), Agreement Across Borders (University of Zadar), and the University of Nova Gorica (January 2015). Special thanks go to the speakers who took part in my survey on the pcc in Slovenian. This paper improved greatly thanks to comments from four anonymous NLLT reviewers, as well as the editor Julie Legate. Finally, I would like to again thank Jonathan, Susi, and especially Željko, for reading and commenting on my drafts and for their guidance. The remaining errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stegovec, A. Taking case out of the Person-Case Constraint. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 38, 261–311 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-019-09443-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-019-09443-0

in Strong

in Strong  to SpecvP and be [π]-valued there. Recall that object reordering can occur in Slovenian before v enters the derivation, so either

to SpecvP and be [π]-valued there. Recall that object reordering can occur in Slovenian before v enters the derivation, so either  always enforces the immediate deletion of [uπ] on v (cf. (43)), thus leaving the

always enforces the immediate deletion of [uπ] on v (cf. (43)), thus leaving the  without a source of valued [π] even if it moved to SpecvP. As it does not matter for the present discussion which of the options is correct, I leave teasing them apart for future work.

without a source of valued [π] even if it moved to SpecvP. As it does not matter for the present discussion which of the options is correct, I leave teasing them apart for future work. , and one parallel to (iii)—where it is deleted. Since valued and default

, and one parallel to (iii)—where it is deleted. Since valued and default